Abstract

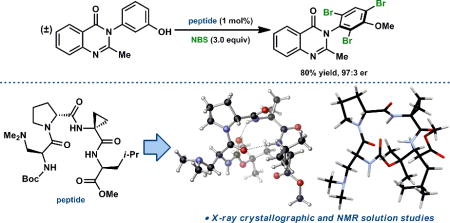

We describe herein a crystallographic and NMR study of the secondary structural attributes of a β-turn-containing tetra-peptide, Boc-Dmaa-D-Pro-Acpc-Leu-NMe2, which was recently reported as a highly effective catalyst in the atroposelective bromination of 3-arylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones. Inquiries pertaining to the functional consequences of residue substitutions led to the discovery of a more selective catalyst, Boc-Dmaa-D-Pro-Acpc-Leu-OMe, the structure of which was also explored. This new lead catalyst was found to exhibit a type I’ β-turn secondary structure both in the solid state and in solution, a structure that was shown to be an accessible conformation of the previously reported catalyst, as well.

Graphical abstract

In the field of asymmetric catalysis, certain catalyst platforms have emerged as “privileged” chiral scaffolds due to their ability to achieve high levels of enantioinduction across a wide array of synthetically useful transformations.1 One feature common to many of these scaffolds is a minimum of rotatable bonds, which presumably allows for the formation of rigid and well-defined transition states. Peptide-based catalysis has also proven to be an effective strategy for the synthesis of optically enriched compounds.2 Detailed analyses of structural trends in proteins,3 as well as physical organic studies of oligopeptides in organic solution,4 have enabled the design of specific peptide secondary structures with high precision. Nonetheless, the many bond rotations available to short peptides provides the possibility that these peptidic catalysts may exist as an equilibrial mixture of conformers under the reaction conditions, both in low energy ground states and in competing transition states.4,5 Deciphering which of these conformers, if any, are kinetically-competent has been an on-going challenge in the field.6

Our laboratory has often capitalized on the secondary structural preferences of certain peptide sequences in optimizing lead catalysts for various asymmetric transformations. One motif in particular has been very fruitful in terms of catalyst development. The Pro-Xaa sequence, where Pro is D- or L-proline and Xaa is an α, α-disubstituted, achiral amino acid residue (often Aib§), reliably nucleates a type II (or II’) β-turn secondary structure when located in the loop region (i.e. the i+1 and i+2 positions, respectively) of a tetrapeptide.7 We have reported a number of catalytic, asymmetric methods that take advantage of the Pro-Xaa structural motif.8 The atroposelective bromination of 3-arylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones (1) is a recent example, in which we identified the D-Pro-Acpc§-containing peptide 3 as an effective catalyst (Scheme 1).9 The catalytic Dmaa§ residue was embedded at the i-position of the turn for functional group cooperativity with the backbone amides. Employing optimized conditions (slow addition of NBS§ over 2.5 hours), 3 provided good yields and excellent enantioselectivities over a broad substrate scope.9

Scheme 1.

Atroposelective Bromination of 3-Arylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones (1)

Catalyst 3 emerged from a systematic optimization of the peptide sequence, in which Acpc-containing peptides were found to be superior to other i+2 variants, providing tribrominated quinazolinone 2 in 35–40% ee§ higher than the corresponding Aib-containing peptides.9 The decision to examine Acpc as an i+2-residue in our catalyst optimization studies was motivated by the search for different Aib-variants for this crucial turn position in pursuit of higher ee values. While we anticipated that the geometric constraints imposed by the cyclopropyl ring would influence the secondary structure in some way, we were unsure of what those effects might be. With excellent catalyst performance in hand, we turned our attention to structural studies of this catalyst family, aspiring to better understand, and perhaps eventually predict, the effects of residue substitutions during catalyst optimization.

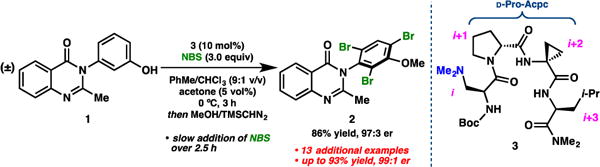

In our previous report,9 we were able to grow a single crystal of 3 using slow vapour diffusion of pentane into a nearly saturated solution of 3 in ethyl acetate. X-Ray diffraction provided a unit cell containing two distinct conformers, 3(a) and 3(b) (Figure 1a).9 In an attempt to assess the reproducibility of the crystallization, we re-grew crystals of 3 under nearly identical conditions, and we fortuitously observed a polymorphic unit cell containing yet another conformer (3(c), Figure 1b). The observation of three distinct solid-state conformations of 3 was striking and unexpected. As a harbinger of the conformational diversity of peptide-based catalysts, we were eager to expand our inquiry into their structures.

Figure 1.

Structural diversity in the X-ray crystal structures of 3. (a) Conformers 3(a) and 3(b) are both consistent with type II’ β-hairpin geometries.9 (b) Conformer 3(c) is consistent with a distorted type I’ β-turn. (c) Idealized type I’ and II’ β-turns as classified by the ϕ and ψ dihedral angles of the loop residues.3,10

The X-ray crystal structures of 3 revealed two different turn motifs in the solid state. β-Turn types are typically classified by the ϕ and ψ dihedral angles of the loop residues, in this case ϕ,ψ(i+1) and ϕ,ψ(i+2).3 Idealized dihedrals for types I’ and II’ are shown in Figure 1c. By this analysis, conformers 3(a) and 3(b) are consistent with type II’ β-turns, while 3(c) most closely resembles a type I’ β-turn (Figure 1a,b).

Both 3(a) and 3(b) were found to exhibit strong intramolecular H-bonds between NHLeu and ODmaa and between NHDmaa and OLeu, consistent with those expected for β-hairpin structures (Figure 1a).4,7 An additional seven-membered ring, γ-turn-like H-bond was observed between NHAcpc and ODmaa in 3(a). The bifurcated nature of the H-bonds to ODmaa suggests that, even in the solid state, there is a conformational equilibrium between β- and γ-turn geometries, and that 3(a) is sampling both to some extent (perhaps favouring the β-turn on the basis of bond length).6,11 The γ-turn tendency of 3(a) manifests in the comparatively large difference (25.7°) between τηɛ ψ(i+1) dihedrals of 3(a) and 3(b). Another prominent difference between 3(a) and 3(b) is the degree of backbone bending. We were able to quantify this observation by measuring the angle between two intersecting planes, one defined by the α-carbons of residues i, i+1, i+2, and i+3, and the other by the α-carbons of i–1 (the 3°-carbon of the Boc§-group), i, i+3, and i+4 (the trans-Me of the NMe2 end cap).† The backbone of conformer 3(a) was found to bend 66°, making for a more compact structure, while that of 3(b) is more extended and bends only 41°. The X-ray crystal structure of a related D-Pro-Aib-containing type II’ β-turn, previously reported,12 also exhibits this bent structure, but to a slightly lesser degree (63° bend).

Conformer 3(c) was unanticipated based on our previous studies of Pro-Xaa turns in peptide-based catalysts (Figure 1c). The ϕ,ψ(i+1) and ϕ,ψ(i+2) dihedrals are consistent with a type I’ β-turn, with some clear distortions from ideality. The ψ(i+1) dihedral is 14.8° closer to syn-coplanar than in the ideal case, while ψ(i+2) is 14.9° larger than the ideal. Moreover, the 79.1° ϕ (i+2) dihedral of 3(c) is 19.1° smaller than expected. These dihedral deviations perhaps may be explained by the existence of a strong intramolecular H-bond between NHAcpc and OBoc. It seems plausible that a favourable H-bonding interaction could provide the driving force for modest distortion of the backbone conformation. The ten-membered ring β-turn H-bond is also present in 3(c), though it is slightly longer than in 3(a) and 3(b). The two intramolecular H-bonds observed in this conformer provide a sequential double β-turn geometry reminiscent of a helix. Though unanticipated, this is not surprising given the well-documented helical tendencies of Acpc and its derivatives.13 Nonetheless, our studies reinforce the notion that the i+2 Acpc-residue may not be an innocent Aib-surrogate, as it appears to induce conformational heterogeneity in the ground-state catalyst structures.

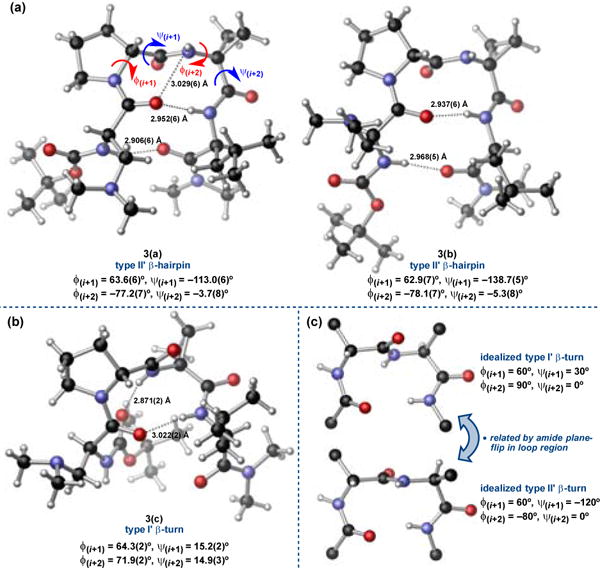

Mechanistic questions arising from these intriguing structural observations stimulated an expanded study of peptide-based catalysts (4) for the bromination of 1 (Figure 2). In particular, we sought to better understand the effects of seemingly subtle changes to the peptide sequence on enantioselectivity. A number of interesting trends emerged from this data set. In our original report,9 optimization of catalyst 3 led to the observation that alkyl-substituted residues, such as Leu and Val, were preferred over Phe-type residues at the i+3 position,† but only within the optimal Acpc-series (4h vs. 3 & 4n). This i+3 alkyl effect proved to be quite general across the different i+2-series. Modest enantio-selectivity increases of 7–10% ee were observed in the Aib-series (4a vs. 4c & 4f), but more drastic increases of about 25% ee were observed in the L-Phe-series (4u vs. 4w). The low-selectivity Aic§-series did not benefit from Leu-substitution to any significant extent (4p vs. 4r). We were also intrigued by the subtle effects of the C-terminal end cap on enantioselectivity. While the dimethyl amides were indeed found to be superior in lower-selectivity regimes (4a vs. 4b, 4c vs. 4d, 4f vs. 4g, & 4p vs. 4q), this trend did not necessarily hold within the more selective catalyst series (4j vs. 4k & 4w vs. 4x). In fact, examination of the methyl ester variant of 3 led to the discovery of a new lead catalyst, 4l, which provided tribromide 2 in 95:5 er§ without recourse to slow addition. Thus, it seems that the methyl esters may be beneficial above some selectivity threshold, especially when paired with Leu at the i+3 position (4l, & 4x). Dimethyl amides are generally presumed to be stronger H-bond acceptors than methyl esters.14 It seems plausible that a weakened NHDmaa to OLeu (hairpin) H-bond could produce a significant geometric change, especially when paired with backbone conformational driving forces, such as the more helical tendencies of Acpc.13

Figure 2.

Peptide structure-function studies led to the discovery of an improved catalyst (4l). Peptides were examined on a 0.05 mmol scale using the above conditions. Some data from ref. 9 are reproduced for clarity.

Perhaps the most intriguing result to emerge from the expanded peptide data set involved the substitution of L-Pro for D-Pro in each i+2 series (Figure 2). This change is expected to induce a conformational shift from the “mirror image” β-turns (types I’ or II’) to the canonical β-turns (types I or II) via an amide plane-flip in the loop region.15 Historically, we have often found that such changes to the catalyst turn sense provided enantioselectivities in favour of the opposite enantiomer with significant erosion of magnitude, especially with Pro-Xaa-containing catalysts.16 Such is the case here in the Aib- and Aic-series; the change from D-Pro-Aib (4d) to L-Pro-Aib (4e) produced a drop from 35% ee to –11% ee, and the change from D-Pro-Aic (4s) to L-Pro-Aic (4t) followed suit (Figure 2). However, the change from D-Pro-Acpc (4l) to L-Pro-Acpc (4m) maintained a high level of enantioselectivity in the opposite direction (–77% ee), which may suggest that absolute enantiocontrol is largely dictated by the turn sense with relatively little contribution from the flanking residues. In our experience, this degree of enantio-divergence is notable and unprecedented, especially for an epimeric catalyst, and it warrants future investigation.

Though more reactive and selective than 3 under the screening conditions (Figure 2), catalyst 4l provided 2 in 92% isolated yield and 97:3 er using the optimized slow addition protocol described in Scheme 1, the same er as observed for 3.† However, we were able to decrease the loading of 4l to 1 mol% with full retention of enantioselectivity (97:3 er) at the expense of moderately diminished yield (80% isolated).

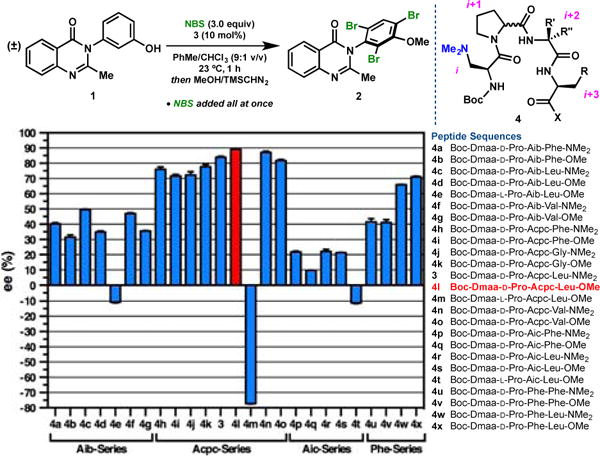

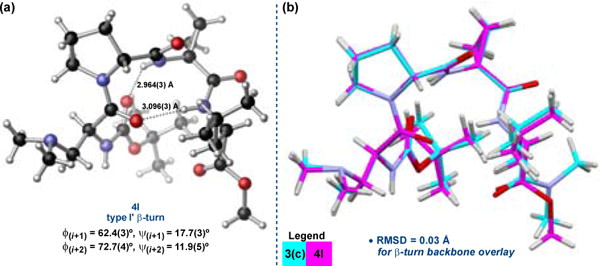

We were also able to grow a single crystal of the new lead catalyst, 4l, using the same slow vapour diffusion technique employed in the crystallization of 3. Interestingly, the crystal was quite fragile and fractured during X-ray diffraction at cryogenic temperatures.† We were eventually able to collect diffraction data at –40 °C without damaging the crystal, though the thermal ellipsoids are quite large as a result. Nonetheless, the unit cell contained only one conformer of 4l, which clearly adopted the same distorted type I’ β-turn as 3(c) (Figure 3a). In fact, the two structures overlay remarkably well, with an RMS deviation of only 0.03 Å in the β-turn backbone (Figure 3b).† The intramolecular H-bonding network is nearly identical, as well, exhibiting the same sequential bis-β-turn that renders the structure helical.

Figure 3.

(a) The X-ray crystal structure of 4l was also found to exhibit a type I’ β-turn geometry.10 (b) Structural overlay of the X-ray crystal structures of conformer 3(c) and 4l.

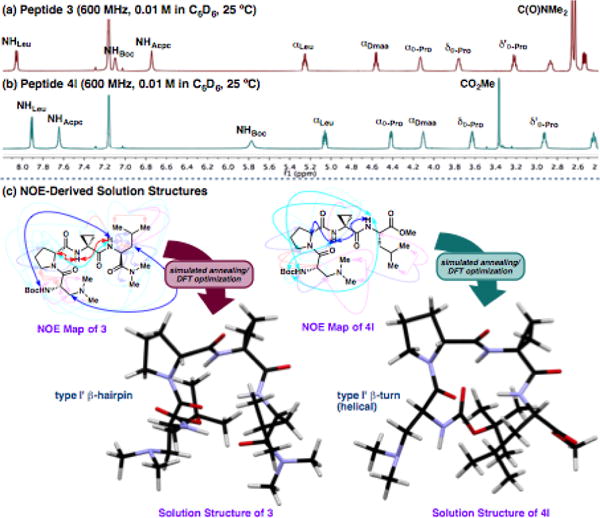

To obtain structural insight under conditions more analogous to the reactions conditions, we complemented the solid-state analysis with solution-phase NMR studies of 3 and 4l in d6-benzene. It is clear from a simple overlay of the two 1H-NMR spectra that they exhibit, on average, in different structures (Figure 4a,b). Notably, the NHBoc signal of 3 is 1.28 ppm further downfield than that of 4l, while the NHAcpc signal of 4l is 0.93 ppm further downfield than that of 3. These data are consistent with a difference in the H-bonded state of the two peptides that is consistent with the crystallographic data.† To investigate these trends at higher resolution, we modelled the solution structures of 3 and 4l using 2D-NMR and computational techniques. We acquired 1H-1H NOESY data on both peptides and integrated the non-sequential NOESY cross-peaks to derive distance restraints,17 which were then used in a simulated annealing protocol.† Geometry optimization of the annealing outputs using DFT§ at the B3LYP/6-31G** level of theory provided NMR-derived solution structures (Figure 4c).†

Figure 4.

Overlay of the 1H-NMR spectra of (a) 3 and (b) 4l showing distinct differences in the hydrogen-bonding networks. (c) NOESY data was used to compute solution structures of 3 and 4l.†

In peptide 3, we were able to observe NOE§ interactions between NHLeu↔NHAcpc, NHLeu↔NHDmaa, βDmaa↔βLeu, NHLeu↔ αD-Pro, and NHAcpc↔αD-Pro. A type I’ β-hairpin structure was apparent in the computed structure (Figure 4c), which seems to possess certain characteristics of all three solid-state conformers 3(a–c). It shows the loop region dihedrals of 3(c), the backbone bending of 3(b), and the NHBoc to OLeu hairpin H-bond observed in both 3(a) and 3(b) in place of the NHAcpc to OBoc H-bond of 3(c). The hybrid nature of the NMR-derived solution structure may reflect a time average of multiple equilibrating conformers in solution. On the other hand, the solid- and solution-state structures of 4l coincided more closely. Particularly relevant through-space interactions are observed between NHLeu↔NHAcpc, NHLeu ↔t-BuBoc, NHAcpc↔αD-Pro, NHAcpc↔ δD-Pro, δD-Pro↔βAcpc, ανδ δ϶D-Pro↔βAcpc.. These turn-consistent features were also corroborated in the calculated structure, which produced a type I’ β-turn similar to the solid-state structure of 4l (Figure 4c). These results reflect the subtle consequences of swapping the C-terminal functional group in an otherwise identical sequence. It seems as though the favourable driving force to form a β-hairpin H-bond to the dimethyl amide acceptor of 3 is counterbalanced by the helical preferences of the D-Pro-Acpc turn motif observed in the solid-state, while there is less of a tendency to hairpin formation to the weaker methyl ester acceptor of 4l.

In conclusion, we have shown that short sequence peptide-based catalysts exhibit greater conformational diversity than one might anticipate on the basis of design principles. Our results provide evidence that there may be some tolerance of, or even benefit to, catalyst flexibility, as we are able to achieve high enantioselectivities in the bromination of 1 using these peptides. However, this structural flexibility also complicates the process of mechanistic analysis. Of course, it is possible that the kinetically competent species is an all-together different conformer, or that conformational changes occur in a Curtin-Hammett-type fashion to access the active catalyst. In any case, the experimental observation of multiple conformations and turn types speaks to the challenges associated with studying conformationally dynamic catalysts. Experimentally restrained computational approaches may assist in the path forward.18

We would like to extend our sincerest thanks to Dr. Byoungmoo Kim for helpful discussions and Matthew E. Diener early contributions to this project. We also thank the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH (GM-068649) for financial support. A.J.M. gratefully acknowledges financial support from the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program. Computational work was supported by the Yale University Faculty of Arts and Sciences High Performance Computing Center, and by the NSF under grant #CNS 08-21132 that partially funded acquisition of the facilities.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: synthetic procedures, characterization, crystallographic information, and NMR/computational data are provided. CCDC 1453124 (3(c)) and 1453125 (4l). See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x.

Abbreviations Aib, aminoisobutyric acid; Aic, 2-aminoindane-2-carboxamide; Acpc, 1-aminocyclopropyl-1-carboxamide; Boc, N-tert-butoxy carbamate; DFT, density functional theory; Dmaa, L-β-dimethylaminoalanine; ee, enantiomeric excess; er, enantiomer ratio; NBS, N-bromosuccinimide; NOE, nuclear Overhauser effect

Notes and references

- 1.Yoon TP, Jacobsen EN. Science. 2003;299:1691. doi: 10.1126/science.1083622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q-L, editor. Privileged Chiral Ligands and Catalysts. Wiley VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewandowski B, Wennemers H. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2014;22:40. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennemers H. Chem Commun. 2011;47:12036. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15237h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbie Davie EA, Mennen SM, Xu Y, Miller SJ. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5759. doi: 10.1021/cr068377w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilmot CM, Thornton JM. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:221. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson EG, Thornton JM. Protein Sci. 1994;3:2207. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haque TS, Little JC, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6975. [Google Scholar]

- Haque TS, Little JC, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:4105. [Google Scholar]

- Liang G-B, Rito CJ, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:4440. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fierman MB, O’Leary DJ, Steinmetz WE, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6967. doi: 10.1021/ja049661c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsche CE, Peris G, Miller SJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:6707. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For example:; Abascal NC, Lichtor PA, Giuliano MW, Miller SJ. Chem Sci. 2014;5:4504. doi: 10.1039/C4SC01440E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravi A, Venkataram Prasad BV, Balaram P. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:105. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi A, Balaram P. Tetrahedron. 1984;40:2577. [Google Scholar]

- Karle IL, Awasthi SK, Balaram P. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For relevant examples:; Shugrue CR, Miller SJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:11173. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbofana CT, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:3285. doi: 10.1021/ja412996f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett KT, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2963. doi: 10.1021/ja400082x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diener ME, Metrano AJ, Kusano S, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:12369. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CYLview was used to render X-ray crystal data: CYLview, 1.0b. C. Y. Legault, Université de Sherbrooke; 2009. ( http://www.cylview.org). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Marraud M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:5353. [Google Scholar]

- Némethy G, Printz MP. Macromolecules. 1972;5:755. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blank JT, Miller SJ. Biopolymers (Pept Sci) 2006;84:38. doi: 10.1002/bip.20392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toniolo C, Crisma M, Formaggio F, Peggion C. Biopolymers. 2001;60:396. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:6<396::AID-BIP10184>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti E, Di Blasio B, Pavone V, Pedone C, Santini A, Barone V, Fraternelli F, Lelj F, Bavoso A, Crisma M, Toniolo C. Int J Macromol. 1989;11:353. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(89)90007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilli P, Pretto L, Bertolasi V, Gilli G. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:33. doi: 10.1021/ar800001k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayward S. Protein Sci. 2001;10:2219. doi: 10.1110/ps.23101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.For example:; Cowen BJ, Saunders LB, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6105. doi: 10.1021/ja901279m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvo ER, Copeland GT, Papaioannou N, Bonitatebus PJ, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11638. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macura S, Farmer BT, II, Brown LR. J Mag Res. 1986;70:493. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao R-Z, Santoro S, Gotsev M, Marcelli T, Himo F. ACS Catal. 2016;6:1165. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal N, Lippert KM, De CK, Klauber EG, Emge TJ, Schreiner PR, Seidel D. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:5748. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.