Abstract

Cdc42 belongs to the Rho family of small GTPases and plays key roles in cellular events of polarity. This role of Cdc42 has typically been attributed to its function at the plasma membrane. However, Cdc42 also exists at the Golgi complex. In this review, we summarize major insights that have been gathered in studying the Golgi-pool of Cdc42 and propose that Golgi-localized Cdc42 enables the cell to diversify the function of Cdc42, which in some cases represent new roles, and in other cases act to complement the established roles of Cdc42 at the plasma membrane. Studies on how Cdc42 acts at the Golgi also suggest key questions to address in the future.

Keywords: Cdc42, Golgi, COPI, polarity, cell migration

Cdc42 acts not only at the plasma membrane but also at the Golgi

Small GTPases play integral roles in intracellular signal transduction pathways. Thus, they are involved in the regulation of virtually all cellular processes [1–4]. Small GTPases typically act as molecular switches, cycling between the active (GTP-bound) and the inactive (GDP-bound) state. In their active state, these GTPases are typically localized to cellular membranes. As such, a current concept has been that compartmentalization of signaling molecules through membrane localization provides a major mechanism by which the outcome of intracellular signal transduction can be modulated [4–6].

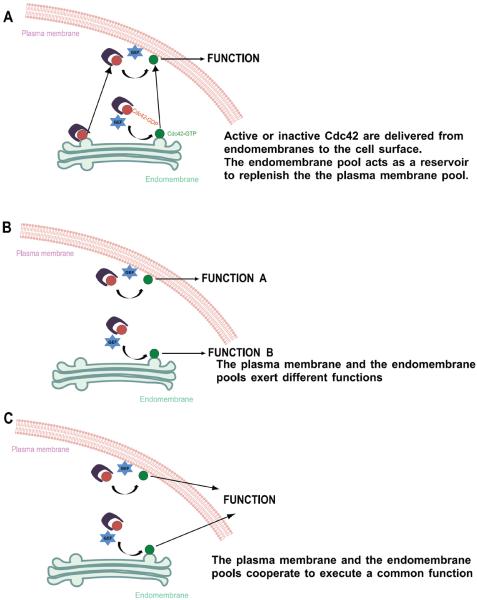

In the case of Cdc42, a member of the Rho family of small GTPases [7,8], distinct pools have been found in different subcellular membrane compartments. These include the plasma membrane, the Golgi complex, and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [9,10]. The pool of Cdc42 at the plasma membrane has been well documented to play key roles in polarity and in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton (Box 1) [6]. Interest developed in understanding the role of the Golgi pool, when cell-based studies uncovered that this pool is activated under certain circumstances [11]. Studies have suggested three general ways that Cdc42 can act at the Golgi: i) acting as a reservoir to replenish the pool at the plasma membrane, ii) having a function independent of the pool at the plasma membrane, and iii) coordinating with the pool at the plasma membrane to achieve polarity events (summarized in Figure 1). Key studies that have contributed to this understanding are discussed below.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the three basic modes of action of Cdc42 at endomembranes. A, the endomembrane pools acts as a reservoir to replenish the plasma membrane. Inactive Cdc42 (red circle) is GDI bound in the cytosol and becomes membrane associated upon activation. Active Cdc42 (green circle) might be delivered from the Golgi to the plasma membrane. Likewise, inactive Cdc42 might be delivered to the plasma membrane to be activated there. The biologic effects of Cdc42 are exerted at the plasma membrane. B, the endomembrane Cdc42 pool exerts different functions than the plasma membrane pool. Cdc42 is activated locally on both endomembranes as well as on the plasma membrane separately. Each pool exerts a different biologic function. C, Cdc42 is activated locally on both endomembranes as well as on the plasma membrane separately and both pools cooperate to exert a common biologic output.

The Golgi pool acts as a reservoir for the plasma membrane pool

The possibility that the Golgi pool of Cdc42 could serve as a reservoir for the pool at the plasma membrane was initially suggested by a yeast study that sought to examine how Cdc42 acts in polarity in the absence of external cues [12]. In this study, the targeted delivery of Cdc42 to a localized region of the plasma membrane was found to require the actin cytoskeleton and also a myosin motor [12]. Delivery of Cdc42 was also found to be dependent on the exocyst [12], which is a multimeric complex that acts to dock Golgi-derived vesicles with the plasma membrane [13]. Thus, these findings suggested that Cdc42 at the Golgi is transported to the plasma membrane to exert cellular polarity.

Subsequently, mammalian studies also suggested that Cdc42 at the Golgi can be transported to the plasma membrane to exert function. In one study, a reporter construct was generated by fusing a domain from an effector of Cdc42, Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Protein (WASP), to a fluorescent dye. This reporter changed its fluorescence intensity in proportion to the level of active Cdc42. Using this approach, the study found that activation of Cdc42 at the Golgi coincided with activation of Cdc42 at the plasma membrane [11]. Moreover, the disruption of microtubules affected total cellular activity of Cdc42 [11]. Thus, because microtubules are involved in transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane, the collective considerations suggested that mammalian Cdc42 at the Golgi could be replenishing the pool at the plasma membrane. Further supporting this possibility, a recent study has found that blocking transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane decreases the activity of Cdc42 at the leading edge of migrating cells [14].

In an interesting twist, the small GTPase ADP-Ribosylation Factor 6 (ARF6) has also been found to be required for the replenishment of cdc42 at the cell surface [15]. ARF6 acts in the endocytic pathway by promoting endocytosis at the plasma membrane, and also recycling, which involves transport from a sub-compartment of the early endosome (known as the recycling endosome) to the plasma membrane [16]. How can a requirement for ARF6 be reconciled with studies that have suggested the importance of delivery from the Golgi? A potential explanation comes from the consideration that transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane can occur indirectly, involving transit through the recycling endosome compartment [17]. Indeed, it was shown that delivery of Cdc42 together with beta-PIX (a guanine nucleotide exchange factor that activates Cdc42) is ARF6-dependent [15]. Thus, the collective observations suggest that Golgi-localized Cdc42 can be delivered to the plasma membrane in two general ways, either directly or indirectly, through the recycling endosome.

Although studies on mammalian Cdc42 have been conducted using different cell types, the results are predicted to be generalizable, as transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane and cell migration are fundamental cellular processes. A replenishing role for the Golgi pool of Cdc42 could serve another major purpose. A well-established mechanism of regulating the recruitment of Cdc42 to the plasma membrane involves the guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI), which acts to bind cytosolic Cdc42 in modulating its recruitment to target membrane. However, a replenishing role for Cdc42 suggests yet another regulatory mechanism, in this case involving transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane. Related to this possibility, one can also envision that regulators and effectors of Cdc42 can be delivered from the Golgi to the plasma membrane in modulating the function of Cdc42 at the plasma membrane.

The Golgi pool acts independently of the plasma membrane pool

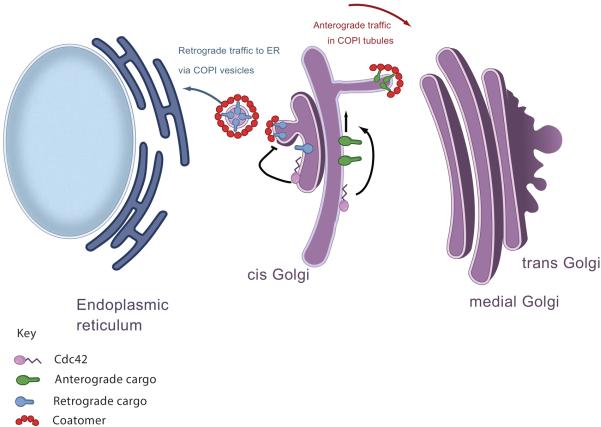

The Golgi pool of Cdc42 can also act independently of its pool at the plasma membrane. In mammalian cells, the Golgi is formed by a series of flattened cisternae, which can be subdivided into the cis, medial, and trans regions [18]. Early studies had suggested that transport within the Golgi stacks occurs through vesicles formed by the Coat Protein I (COPI) complex [19]. Subsequently, intra-Golgi transport was found to be more complex, with the movement of the Golgi stacks mediating anterograde transport (known as cisternal maturation), and vesicles formed by the COPI complex mediating retrograde transport [20].

An initial hint that Cdc42 acts on intra-Golgi transport came from the observation that Cdc42 interacts with coatomer [21], which is a multimeric complex that constitutes the core components of the COPI complex [22]. Specifically, Cdc42 was found to compete with cargo proteins for binding to coatomer [21]. Thus, it was speculated that Cdc42 acts to inhibit retrograde Golgi transport by inhibiting the sorting of retrograde cargoes into COPI vesicles [21]. Recently, a more refined understanding of how Cdc42 acts in Golgi transport has been achieved. Besides generating vesicles for retrograde Golgi transport, COPI has been found to generate tubules, which connect the Golgi stacks in promoting anterograde Golgi transport [23].

Following up on this discovery, a recent study has found that Cdc42 not only inhibits the sorting of retrograde cargoes into COPI vesicles, but also promotes the formation of COPI tubules to enhance anterograde Golgi transport [24]. Although vesicle and tubule formation are both initiated by the formation of COPI buds from Golgi membrane, vesicle formation involves the subsequent constriction of the bud neck that eventually results in vesicles being released from organellar membrane, a process known as vesicle fission. Cdc42 was found to promote COPI tubule formation through two complementary mechanisms, promoting the initial budding process and also inhibiting the subsequent fission process, which then diverts COPI vesicle formation toward tubule formation [24]. Overall, by modulating the two major functions of the COPI complex (Figure 2), cargo sorting and carrier formation, Cdc42 polarizes transport at the Golgi to favor the anterograde direction [24].

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the opposing role Cdc42 on regulation of anterograde and retrograde COPI trafficking. The COPI coat mediates retrograde transport to the ER in small vesicles and this is suppressed by active Cdc42 at the Golgi. At the same time, anterograde intra-Golgi trafficking is mediated via COPI coated tubules and this trafficking step is supported by active Cdc42 at the Golgi.

Other studies have suggested additional ways that Cdc42 at the Golgi could impact on COPI transport. Cdc42 has been found to modulate the recruitment of dynein onto COPI vesicles, which suggests a microtubule-based mechanism that can dictate the directionality of COPI transport at the Golgi [25]. The same study also found that actin dynamics play a role in the recruitment of dynein to COPI carriers [25]. Further defining how Cdc42 acts, another study has uncovered an actin-based mechanism, which involves WASP promoting COPI transport [26]. Notably, because COPI had been thought for many years to act only in generating vesicles for retrograde Golgi transport, both the actin- and the microtubule-based mechanisms were only studied in the context of retrograde COPI vesicular transport. However, in light of the more recent appreciation that COPI also promotes anterograde Golgi transport through the generation of tubules [23], how the different cytoskeleton-based mechanisms affect COPI transport will need to be re-evaluated.

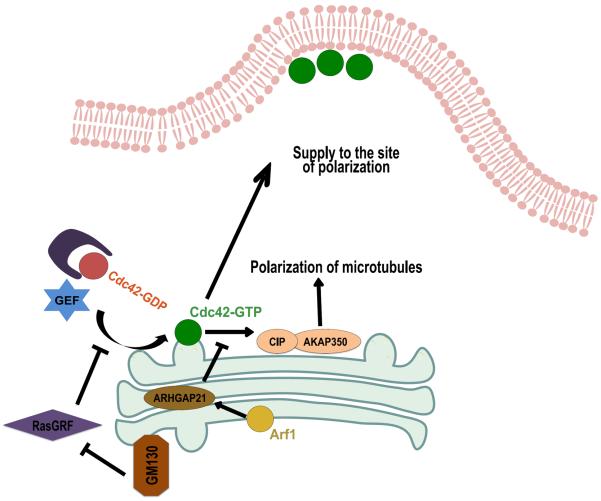

The Golgi pool acts in conjunction with the plasma membrane pool

Golgi-localized Cdc42 can also act by coordinating its function with the pool at the plasma membrane for complex events of cellular polarity. One such role involves Cdc42 controlling the positioning of the Golgi. In directed cell migration, it is well known that the Golgi polarizes towards the direction of cell movement, and that altering this polarization impairs cell migration [27,28]. This role of Cdc42 has been found to be dependent on microtubules, and also under the control of ARHGAP21, a protein that catalyzes the deactivation of Cdc42 [29]. More recently, AKAP350, a Golgi-localized protein involved in the nucleation of microtubules, has been found to interact with CIP4, which acts as an effector of Cdc42 in promoting the polarity of migrating cells [30].

To ascertain that Cdc42 at the Golgi acts in conjunction with the pool at the plasma membrane for polarity events, studies have also sought to track the different sub-cellular pools of Cdc42 more directly. Spatial activation of Cdc42 has been directly visualized through reporters that are based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) [31]. These reporters, known as Raichu, are single polypeptides generated by linking Cdc42 to an effector domain and coupling this fusion construct to a fluorescent dye. Using this approach, a recent study has revealed that the leading edge of migrating cells have higher levels of active Cdc42 as compared to its trailing edges [14]. Notably, this asymmetry of Cdc42 activity was found to be dependent on the presence of active Cdc42 at the Golgi and also on membrane transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane. Thus, the ability of Cdc42 to position the Golgi allows the polarized delivery of secretory traffic to specific regions of the plasma membrane in achieving directional cell migration.

Another consideration is that the post-Golgi traffic should result in the expansion of membrane at the cell surface. Thus, if more membrane is delivered than Cdc42, the net effect could be a dilution of Cdc42 concentration on the plasma membrane. In this regard, it has been shown in yeast that a local autocatalytic positive feedback together with an endocytosis-based corralling mechanism ensures that exocytosis is a driving factor for polarization [32,33]. Whether a similar mechanism exists in mammalian cells remains to be elucidated.

Concluding Remarks

We have highlighted above three general ways that the Golgi pool of Cdc42 can act (summarized in Figure 1). As such, it appears that the Golgi-localized Cdc42 enables the cell to diversify the function of this small GTPase, which in some cases represent new roles, and in other cases act to complement its established roles at the plasma membrane. The elucidation of how Cdc42 acts at the Golgi also suggests key issues for further clarification in the future (see Outstanding Questions).

First, whether Golgi-localized Cdc42 acts in a replenishing role or in a coordinating role with the pool at the plasma membrane need not be mutually exclusive. Indeed, the collective results on how Cdc42 acts in directional cell migration suggest that both mechanisms likely act in concert in achieving this complex example of polarity. A better understanding of their relative contribution will likely come from the ability to track distinct pools of Cdc42 in the cell. Indeed, FRET-based microscopy has been used recently to uncover that GM130, a Golgi-localized protein, regulates Cdc42 at the Golgi without affecting its pool at the plasma membrane [14] (Figure 3). Similarly, a variation of the FRET technique, known as fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM), has been used recently to provide more conclusive evidence that Cdc42 at the Golgi affects the interaction between cargo and the COPI complex [24]. Thus, we anticipate that the further application of these advanced approaches of microscopy will provide better clarity in the future regarding the relative contributions of Cdc42 at the Golgi versus that at the plasma membrane in complex examples of polarity, such as directional cell migration.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the regulation of Cdc42 at the Golgi and its role in cell polarization. The Golgi matrix protein GM130 sequesters RasGRF, an inhibitor of Cdc42 activation. Cdc42 at the Golgi may lead to recruitment and activation of the CIP-AKAP350, which promotes the polarization of microtubules towards the site of polarization. Active Cdc42 maybe itself delivered to the site of polarization, thereby sustaining polarity. At the Golgi, Cdc42 is subject to deactivation by ARHGAP21, which is recruited to the Golgi in a manner dependent on the small GTPase Arf1.

Second, it will be interesting to determine whether the ability of Cdc42 to modulate bidirectional COPI transport at the Golgi is important for directional cell migration. Although Cdc42 has been found to promote anterograde Golgi transport by a recent study, the study has further defined that Cdc42 acts to promote a faster rate of anterograde transport than the basal rate achieved by cisternal maturation [20]. Thus, further work will be needed to determine whether a faster rate of anterograde Golgi transport induced by Cdc42 is critical for directional cell migration, or might the basal rate of transport mediated by cisternal maturation be sufficient.

Third, the involvement of the actin and the microtubule cytoskeleton has been a recurrent theme for how Golgi-localized Cdc42 acts. However, most studies have examined the roles of these two cytoskeletal processes independent of each other. Thus, a more sophisticated understanding will likely be attained in the future by examining how both cytoskeleton-based mechanisms acts in concert to achieve specific circumstance of cellular polarity that require the Golgi pool of Cdc42. Future studies will also be needed to explore other Cdc42 effectors that have been found to have a Golgi pool, such as IQGAP [34]. In this regard, a method with strong potential involves optogenic tools that can spatiotemporally modulate the actions of Cdc42. The feasibility of such an approach is illustrated by recent advances where optogenetic approaches were used to control organelle positioning [35], as well as the activity of another Rho family GTPase, Rac1 [36].

Fourth, a general mechanistic paradigm has been that distinct functions of small GTPases can be achieved through coupling to their key classes of regulators, guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs). Besides playing critical roles in catalyzing the activation and deactivation of small GTPases, these key regulators also act to specify the location and the interacting partners for specific pools of small GTPases [3]. In this regard, although GEFs and GAPs are predicted to exist for the Golgi pool of Cdc42, their identification has not been straightforward. FDG1, a GEF for Cdc42 has been localized to the Golgi [37]. However, whether it acts on the Golgi pool of Cdc42 has been questioned [14]. Another GEF that was previously reported to localize to the Golgi is TUBA [38]. However, this finding has also been controversial, as multiple other groups have not been able to replicate the finding [14, 39, 40]. Similarly, with the exception of ARHGAP21 (also known as ARHGAP10), which has been localized to the Golgi to some extent [41], how other GAPs can potentially regulate the Golgi pool of Cdc42 needs to be investigated. Besides GEFs and GAPs, other mechanisms of regulating Cdc42 are emerging. For example, Golgi-localized Cdc42 has been found recently to be regulated by a Ras GEF, known as RasGRF, which involves its binding to Cdc42 to prevent activation by relevant GEF(s) [14]. Another possibility comes from studies on the Ras small GTPase. It has been suggested that active Ras at the Golgi is an “echo” of Ras that has been activated at other cellular locations [42]. Thus, we anticipate that additional novel mechanisms in regulating Cdc42 at the Golgi will be uncovered in the future.

Fifth, Cdc42 has been found recently to possess an intrinsic ability to bend membrane in promoting the formation of COPI tubules at the Golgi [24]. This discovery is remarkable, as it is uncovering an effector function of Cdc42, in contrast to its currently known functions, which involve roles as upstream regulator of cellular events. Thus, an intriguing prospect is that other examples of effector function for Cdc42 will be uncovered in the future.

Finally, we note that a better understanding of how Cdc42 acts at the Golgi has shed key insights into pathophysiology, such as cancer biology. The finding that Cdc42 plays a critical role in cellular transformation has led to the discovery that its Golgi pool plays a key role in this process through interaction with coatomer [21], which modulates bidirectional COPI transport to achieve the polarization of Golgi transport [24]. Moreover, another study has shown recently that the aberrant regulation of Cdc42 at the Golgi by GM130 potentially contributes to colonic and breast cancer [14, 43]. As such, the different lines of future investigation that we have outlined above have the prospect of advancing not only a basic understanding of how Cdc42 acts at the Golgi, but also how this pool plays key roles in human diseases.

Box 1: Cdc42 and its roles at the plasma membrane.

As a small GTPase, Cdc42 is GDP-bound in its inactive state and is kept soluble in the cytosol by binding to GDIs. Cdc42 is activated upon interaction with GEFs. In its GTP-bound active state, Cdc42 engages effectors to promote its biologic functions. The vast majority of research has been centered on studying the roles of Cdc42 at the plasma membranes. Several polarity-inducing stimuli activate Cdc42, such as receptor tyrosine kinases, adhesion molecules (cadherins), and G-protein coupled receptors [8]. Active Cdc42 binds to the plasma membrane, preferably to domains enriched in phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bis-phosphate, which are maintained by PTEN [44]. Cdc42 binds to WASP and thereby activating the Arp2/3 complex resulting in the formation of membrane protrusions, such as filopodia [8]. Cdc42 also activates the Par complex, which contains atypical protein kinase C (aPKC). Active aPKC suppresses Glycogen synthase kinase 3β leading to the association of the adenomatous polyposis coli protein (APC) with microtubule plus-ends and their stabilization at the leading edge of migrating cells [8]. Plus-ends of microtubules are also stabilized by Cdc42-dependent recruitment of IQGAP and the plus-end protein CLIP-170 [45]. The stabilization of microtubules at the leading edge of migrating cells promotes the reorientation of the MTOC towards the direction of migration.

Outstanding questions.

How is Golgi-localized Cdc42 regulated?

Does Golgi-localized Cdc42 modulate cytoskeletal dynamics and is this relevant for cell polarity and migration?

Is the ability of Cdc42 to modulate bidirectional COPI transport at the Golgi is important for directional cell migration?

What is the functional impact of dysregulation of Cdc42 at the Golgi in tumors and can this be targeted therapeutically?

Does Cdc42 have any other effector functions besides its ability to impart membrane curvature on Golgi membranes?

Trends Box.

Cdc42 exists and functions at the plasma membrane and at the Golgi.

Cdc42 can replenish the pool at the plasma membrane via transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane, which can occur either directly or indirectly by additional transit through the recycling endosome.

Cdc42 can act distinctly from the pool at the plasma membrane. A major way involves Cdc42 regulating bidirectional Golgi transport, acting to prevent retrograde cargoes from being sorted into COPI vesicles and also promoting the formation of COPI tubules that act in anterograde Golgi transport.

Cdc42 can act in conjunction with the pool at the plasma membrane. One example is Cdc42 regulating the positioning of the Golgi complex. By coordinating this role with Cdc42 acting at the plasma membrane, surface protrusions are generated at the leading edge of migrating cells.

Acknowledgements

Work by the Farhan laboratory is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, by the German Science Foundation, by the Young Scholar Fund of the University of Konstanz and by the Biotechnology Institute Thurgau. Work by the Hsu laboratory is funded by the National Institute of Health (GM058615).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Colicelli J. Human RAS superfamily proteins and related GTPases. Sci STKE. 2004;2004:RE13. doi: 10.1126/stke.2502004re13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wennerberg K, Rossman KL, Der CJ. The Ras superfamily at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:843–846. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitin N, Rossman KL, Der CJ. Signaling interplay in Ras superfamily function. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R563–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fehrenbacher N, Bar-Sagi D, Philips M. Ras/MAPK signaling from endomembranes. Mol Oncol. 2009;3:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bos JL, Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A. GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell. 2007;129:865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farhan H, Rabouille C. Signalling to and from the secretory pathway. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:171–180. doi: 10.1242/jcs.076455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heasman SJ, Ridley AJ. Mammalian Rho GTPases: new insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:690–701. doi: 10.1038/nrm2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etienne-Manneville S. Cdc42--the centre of polarity. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1291–1300. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson JW, Zhang C.j., Kahn RA, Evans T, Cerione RA. Mammalian Cdc42 is a brefeldin A-sensitive component of the Golgi apparatus. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26850–26854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michaelson D, Silletti J, Murphy G, D'Eustachio P, Rush M, Philips MR. Differential localization of Rho GTPases in live cells: regulation by hypervariable regions and RhoGDI binding. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:111–126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nalbant P, Hodgson L, Kraynov V, Toutchkine A, Hahn KM. Activation of endogenous Cdc42 visualized in living cells. Science. 2004;305:1615–1619. doi: 10.1126/science.1100367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wedlich-Soldner R, Altschuler S, Wu L, Li R. Spontaneous cell polarization through actomyosin-based delivery of the Cdc42 GTPase. Science. 2003;299:1231–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.1080944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu IM, Hughson FM. Tethering factors as organizers of intracellular vesicular traffic. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:137–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baschieri F, Confalonieri S, Bertalot G, Di Fiore PP, Dietmaier W, Leist M, Crespo P, Macara IG, Farhan H. Spatial control of Cdc42 signalling by a GM130-RasGRF complex regulates polarity and tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4839. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osmani N, Peglion F, Chavrier P, Etienne-Manneville S. Cdc42 localization and cell polarity depend on membrane traffic. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1261–1269. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donaldson JG, Jackson CL. ARF family G proteins and their regulators: roles in membrane transport, development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:362–375. doi: 10.1038/nrm3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ang AL, Taguchi T, Francis S, Folsch H, Murrells LJ, Pypaert M, Warren G, Mellman I. Recycling endosomes can serve as intermediates during transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane of MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:531–543. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glick BS, Nakano A. Membrane traffic within the Golgi apparatus. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:113–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothman JE, Orci L. Molecular dissection of the secretory pathway. Nature. 1992;355:409–415. doi: 10.1038/355409a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakano A, Luini A. Passage through the Golgi. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu WJ, Erickson JW, Lin R, Cerione RA. The gamma-subunit of the coatomer complex binds Cdc42 to mediate transformation. Nature. 2000;405:800–804. doi: 10.1038/35015585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu VW, Lee SY, Yang JS. The evolving understanding of COPI vesicle formation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:360–364. doi: 10.1038/nrm2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang JS, Valente C, Polishchuk RS, Turacchio G, Layre E, Moody DB, Leslie CC, Gelb MH, Brown WJ, Corda D, Luini A, Hsu VW. COPI acts in both vesicular and tubular transport. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:996–1003. doi: 10.1038/ncb2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park SY, Yang JS, Schmider AB, Soberman RJ, Hsu VW. Coordinated regulation of bidirectional COPI transport at the Golgi by CDC42. Nature. 2015;521:529–532. doi: 10.1038/nature14457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JL, Fucini RV, Lacomis L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Stamnes M. Coatomer-bound Cdc42 regulates dynein recruitment to COPI vesicles. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:383–389. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200501157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luna A, Matas OB, Martinez-Menarguez JA, Mato E, Duran JM, Ballesta J, Way M, Egea G. Regulation of protein transport from the Golgi complex to the endoplasmic reticulum by CDC42 and N-WASP. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:866–879. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadav S, Puri S, Linstedt AD. A primary role for Golgi positioning in directed secretion, cell polarity, and wound healing. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1728–1736. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Millarte V, Boncompain G, Tillmann K, Perez F, Sztul E, Farhan H. Phospholipase C γ1 regulates early secretory trafficking and cell migration via interaction with p115. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:2263–2278. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-03-0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hehnly H, Xu W, Chen JL, Stamnes M. Cdc42 regulates microtubule-dependent Golgi positioning. Traffic. 2010;11:1067–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tonucci FM, Hidalgo F, Ferretti A, Almada E, Favre C, Goldenring JR, Kaverina I, Kierbel A, Larocca MC. Centrosomal AKAP350 and CIP4 act in concert to define centrosome/Golgi polarity in migratory cells. J Cell Sci. 2015 doi: 10.1242/jcs.170878. paper in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itoh RE, Kurokawa K, Ohba Y, Yoshizaki H, Mochizuki N, Matsuda M. Activation of rac and cdc42 video imaged by fluorescent resonance energy transfer-based single-molecule probes in the membrane of living cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6582–6591. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6582-6591.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jose M, Tollis S, Nair D, Sibarita JB, McCusker D. Robust polarity establishment occurs via an endocytosis-based cortical corralling mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:407–418. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201206081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savage NS, Layton AT, Lew DJ. Mechanistic mathematical model of polarity in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:1998–2013. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-10-0837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCallum SJ, Erickson JW, Cerione RA. Characterization of the association of the actin-binding protein, IQGAP, and activated Cdc42 with Golgi membranes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22537–22544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Bergeijk P, Adrian M, Hoogenraad CC, Kapitein LC. Optogenetic control of organelle transport and positioning. Nature. 2015;518:111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature14128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu YI, Frey D, Lungu OI, Jaehrig A, Schlichting I, Kuhlman B, Hahn KM. A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature. 2009;461:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egorov MV, Capestrano M, Vorontsova OA, Di Pentima A, Egorova AV, Mariggiò S, Ayala MI, Tetè S, Gorski JL, Luini A, Buccione R, Polishchuk RS. Faciogenital dysplasia protein (FGD1) regulates export of cargo proteins from the golgi complex via Cdc42 activation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2413–2427. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-11-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kodani A, Kristensen I, Huang L, Sütterlin C. GM130-dependent control of Cdc42 activity at the Golgi regulates centrosome organization. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1192–1200. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kovacs EM, Makar RS, Gertler FB. Tuba stimulates intracellular N-WASP-dependent actin assembly. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2715–2726. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salazar MA, Kwiatkowski AV, Pellegrini L, Cestra G, Butler MH, Rossman KL, Serna DM, Sondek J, Gertler FB, De Camilli P. Tuba, a novel protein containing bin/amphiphysin/Rvs and Dbl homology domains, links dynamin to regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49031–49043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dubois T, Paleotti O, Mironov AA, Fraisier V, Stradal TE, De Matteis MA, Franco M, Chavrier P. Golgi-localized GAP for Cdc42 functions downstream of ARF1 to control Arp2/3 complex and Factin dynamics. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:353–364. doi: 10.1038/ncb1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lorentzen A, Kinkhabwala A, Rocks O, Vartak N, Bastiaens PI. Regulation of Ras localization by acylation enables a mode of intracellular signal propagation. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra68. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.20001370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baschieri F, Uetz-vonAllmen E, Legler DF, Farhan H. Loss of GM130 in breast cancer cells and its effects on cell migration, invasion and polarity. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:1139–1147. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1007771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin-Belmonte F, Gassama A, Datta A, Yu W, Rescher U, Gerke V, Mostov K. PTEN-mediated apical segregation of phosphoinositides controls epithelial morphogenesis through Cdc42. Cell. 2007;128:383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fukata M, Watanabe T, Noritake J, Nakagawa M, Yamaga M, Kuroda S, Matsuura Y, Iwamatsu A, Perez F, Kaibuchi K. Rac1 and Cdc42 capture microtubules through IQGAP1 and Clip- 170. Cell. 2002;109:873–885. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00800-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]