Abstract

Rationale, aims and objectives

Specialty care referrals have doubled in the last decade. Optimization of the pre-referral workup by a primary care doctor can lead to a more efficient first specialty visit with the patient. Guidance regarding pre-referral laboratory testing is a first step towards improving the specialty referral process. Our aim was to establish consensus regarding appropriate pre-referral workup for common gastrointestinal and liver conditions.

Methods

The Delphi method was used to establish local consensus for recommending certain laboratory tests prior to specialty referral for 13 clinical conditions. Seven conditions from The University of Michigan outpatient referral guidelines were used as a baseline. An expert panel of three PCPs and nine gastroenterologists from three academic hospitals participated in three iterative rounds of electronic surveys. Each panellist ranked each test using a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Local panellists could recommend additional tests for the initial diagnoses, and also recommended additional diagnoses needing guidelines: iron deficiency anaemia, abdominal pain, irritable bowel syndrome, fatty liver disease, liver mass and cirrhosis. Consensus was defined as ≥70% of experts scoring ≥4 (agree or strongly agree).

Results

Applying Delphi methodology to extrapolate externally developed referral guidelines for local implementation resulted in considerable modifications. For some conditions, many tests from the external group were eliminated by the local group (abdominal bloating; iron deficiency anaemia; irritable bowel syndrome). In contrast, for chronic diarrhoea, abnormal liver enzymes and viral hepatitis, all/most original tests were retained with additional tests added. For liver mass, fatty liver disease and cirrhosis, there was high concordance among the panel with few tests added or eliminated.

Conclusions

Consideration of externally developed referral guidelines using a consensus-building process leads to significant local tailoring and adaption. Our next steps include implementation and dissemination of these guidelines and evaluating their impact on care efficiency in clinical practice.

Keywords: consensus, Delphi method, referral guidelines, referrals, specialty care, specialty referrals

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) diseases represent a significant source of morbidity, mortality and cost in the United States [1] and contribute increasingly to referrals from primary care doctors (PCPs) to specialists. Specialty visits have doubled in the last 10 years and referral rates to gastroenterology (GI) have almost tripled despite managed care and proliferation of practice guidelines [2]. Despite the high number of specialty referrals in the United States, the specialty referral process is still in need of improvement [3,4].

Challenges in the current specialty referral process include inappropriate referrals characterized by insufficient information exchange [3,5,6]. Referrals to specialists often do not include an appropriate pre-referral diagnostic evaluation, which contributes to an inefficient first specialty visit, the need for a subsequent follow-up visit and increased health care costs [7–10]. Alternatively, referrals can be unnecessary [3] in that certain symptoms can be diagnosed and managed in primary care. Nonetheless, in most practice settings, there is no standard efficient mechanism for PCPs to know the appropriate pre-referral workup the specialist desires. Addressing these deficiencies by developing explicit recommendations available to referring providers at the point of care could improve the utilization of GI expertise, the co-management between PCPs and gastroenterologists, the patient experience and the cost of care.

However, considerable research has shown that development of practice guidelines is necessary, but not sufficient, to change behaviour [11]. For example, implementation of practice guidelines may be unsuccessful if they are not compatible with local attitudes and beliefs of the providers, as well as patients [11]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to apply a structured consensus-building process to the implementation of 13 different conditions for referrals from primary care to gastroenterology.

Methods

We used a modified Delphi method to develop consensus guidelines for gastroenterology referrals at University of California San Francisco (UCSF). The Delphi method is a methodology developed by RAND/UCLA, which represents the collective opinions of experts with the premise that ‘pooled intelligence’ enhances individual judgment and is one of the most widely used consensus-building methods [12]. An expert panel of three PCPs and nine gastroenterologists (four hepatologists and five gastroenterologists) was recruited across three hospital systems within UCSF, each representing a unique health care delivery system, to participate in three iterative rounds of electronic questionnaires. UCSF Medical Center serves as both a tertiary academic medical centre and a community hospital; the San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH) is the safety-net hospital for the city and county of San Francisco; and the San Francisco VA Medical Center is part of the nation’s largest integrated health care delivery system dedicated to the care of veterans.

Panel selection

Email invitations were sent to all 12 participants. All participants satisfied the following criteria: board certification in their area of specialty and a faculty appointment at UCSF. There was one primary care doctor from each hospital site (one assistant, one associate and one full professor). There were two hepatologists from UCSF and one each from SFGH and VA (two associate and two full professors). Of the five gastroenterologists, there were three from UCSF, and one each from SFGH and VA (three assistant, one associate and one full professor). One gastroenterologist and one hepatologist, both full professors, answered only questions in their fields given the level of specialization in their faculty practice. The remaining specialists answered all the questions. Specialists were nominated by their division chiefs, and PCPS were recommended by medical directors from each primary care site.

Delphi process

Three rounds of email questionnaires (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA) were conducted over a 3-month period. Participants were given 2 weeks to reply to each questionnaire. If responses were not received within a week of the initial email, an email reminder was sent to individual participants. Subsequent questionnaires were developed based upon the panel responses. There was 100% participation for all three rounds of the study.

Round 1

In round 1, the University of Michigan [13] outpatient referral guidelines for gastroenterology were used as a starting point (see Table 1). The degree of importance for all possible tests and evaluations were ranked on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, strongly agree). Via open-ended response, experts suggested additional workup for the proposed set of diagnoses and added additional diagnoses for guideline development (Table 1).

Table 1.

GI and Liver Related Diagnoses Participating in Delphi Study

| University of Michigan Guidelines | Additional suggested diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Abdominal bloating | Iron deficiency anaemia |

| Chronic diarrhoea | Abdominal pain |

| Heartburn | Irritable bowel syndrome |

| Rectal bleeding | Fatty liver disease |

| Abnormal LFTs | Liver mass |

| Hepatitis B | Cirrhosis |

| Hepatitis C |

Round 2

In round 2, experts were shown the group’s median score from the round 1 diagnosis and given the opportunity to re-rank their answer. The panel also ranked the new proposed workup for the diagnoses suggested in round 1. Consensus was defined when at least 70% of experts scored the item at a level of 4 or more (agree or strongly agree).

Round 3

Round 3 consisted of re-scoring feedback only for the additional suggested diagnoses that emerged in round 1 and had received their initial scoring in round 2. The original diagnoses presented in round 1 were not ranked again in round 3.

Analysis

SPSS v.20 (Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all descriptive analyses. We report overall median scores for the relevant clinical criteria and diagnostic tests. For items not meeting consensus criteria, we report the proportion of participants who scored the item at a level of 4 or more (agreed/strongly agreed) regarding degree of importance on the final Delphi round. We also compared median scores by PCP (n = 3) and specialists (n = 9) on selected items. We report differences between PCPs and specialists where there was at least 1 point difference in median score where the lower median score was either a 2 or 3. These were exploratory analyses, and statistical comparisons between PCPs and specialists were not performed because of small sample size.

Results

GI-related diagnoses (refer to Table 2)

Table 2.

GI-related diagnoses

| Diagnoses | Original tests proposed and retained | Original tests proposed and eliminated | Additional tests proposed and retained | Tests proposed and eliminated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal bloating |

|

|

|

|

| Chronic diarrhoea |

|

|

|

|

| Rectal bleeding |

|

|

||

| Heartburn |

|

|

||

| Iron deficiency anaemia |

|

|

||

| Abdominal pain |

|

|

||

| Irritable bowel syndrome |

|

|

BMI, body mass index; CBC, complete blood count; CMP, complete metabolic panel; Cdiff, Clostridium difficile; IgA TTG, IgA tissue transglutaminase; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; stool O&P, stool ova and parasites; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; BID, bis in die (two times a day); Cr, Creatinine.

Abdominal bloating

The final diagnostic workup recommended by local expert panel for abdominal bloating differed considerably from the original guidelines. Much of the original workup was eliminated including communication of the patient’s dietary history, a trial of alcohol and caffeine abstinence, a trial off carbonated beverages, complete blood count (CBC) and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). Only 67% of participants scored a trial off carbonated beverages as 4 or greater and therefore did not meet consensus criteria. Only a trial of a lactose-free diet was retained. One panellist proposed abstinence from gum chewing but this did not achieve consensus criteria.

Chronic diarrhoea

Chronic diarrhoea was defined as a duration >2–4 weeks and occurring in patients <40 years old. All original proposed tests including CBC, TSH, complete metabolic panel (CMP), giardia stool test and IgA tissue transglutaminase (IgA TTG) were retained. In addition, the panel proposed the following studies: stool culture and sensitivity, faecal fat (72-hour faecal fat), stool ova and parasites, Clostridium dificile, faecal white blood cells (WBC), albumin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Of those, faecal WBC, albumin, ESR/CRP were eliminated. There were differences between PCPs and specialists in the scoring of faecal fat (PCP median score 3; GI median score 4.5), C. dificile (PCP median score 3; GI median score 5) and albumin (PCP median score 3; GI median score 4).

Rectal bleeding in a patient age <40 years with straining or hard stools

The panel endorsed all of the following recommendations: a careful anal exam for fissures and/or haemorrhoids, a trial of fibre supplementation and CBC. Furthermore, there was consensus on an additional recommendation to order a colonoscopy if ongoing rectal bleeding persisted despite appropriate measures prior to referral.

Heartburn in patients age <50 years old

There was broad agreement over the original recommendations: CBC, anti-reflux lifestyle measures, a 4–8-week trial of proton pump inhibitor (PPI), careful non-steroidal anti-inflammatory use history, and assessment for alarm symptoms, and ordering of direct esophagogastricduodenoscopy (EGD) in the presence of alarm symptoms. The panel made two additional recommendations that were retained: (1) direct EGD if symptomatic despite twice-daily PPI for at least 4–8 weeks; and (2) direct EGD if male >50 years old with reflux symptoms >5 years with additional risk factors (nocturnal reflux, hiatal hernia, elevated body mass index, tobacco, central obesity.

Iron deficiency anaemia

The proposed tests for iron deficiency anaemia included CBC, iron studies, H. pylori IgG, BUN/Cr and IgA TTG. Of those, the final workup included only CBC and iron studies, eliminating H. pylori IgG, BUN/Cr and IgA TTG. IgA TTG was ranked differently by specialists with a median score of 3 among PCPs and 4 among GIs.

Abdominal pain

For abdominal pain, the original proposed workup was CBC, CMP, amylase, lipase, TSH, iron studies, IgA TTG and H. pylori IgG. H. pylori IgG and IgA TTG did not meet consensus criteria. Iron studies and TSH were also eliminated. There were differences among PCPs and GIs in the ranking of these tests. Both iron studies and TSH were given a median of 2 among PCPs and 3 among GIs.

Irritable bowel syndrome

For irritable bowel syndrome, the original proposed workup was CBC, CMP, amylase, lipase, TSH, H. pylori IgG and IgA TTG. For this diagnosis, iron studies, H. pylori IgG, amylase, lipase and TSH did not meet consensus criteria. For iron studies, there was discrepancy between PCPs, who gave a median score of 2, and GIs who gave a median score of 4. Other discrepancies between PCPs and specialists included ranking of amylase and lipase (PCP median score 4; GI median score 3) and H. pylori IgG (PCP median score 4; GI median score 3).

Liver-related diagnoses (refer to Table 3)

Table 3.

Liver-related diagnoses

| Diagnoses | Original tests proposed and retained | Original tests proposed and eliminated | Additional tests proposed and retained | Tests proposed and eliminated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal liver enzymes cholestatic |

|

|

|

|

| Hepatitic |

|

|

|

|

| AST/ALT <5x ULN |

|

|

||

| Hepatitic |

|

|||

| AST/ALT >5x ULN |

|

|||

| Hepatitis B |

|

|

||

| Hepatitis C |

|

|

|

|

| Fatty liver disease |

|

|||

| Liver mass |

|

|||

| Cirrhosis |

|

|

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; AMA, anti-mitochondrial antibody; ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; ASMA, anti-smooth muscle antibody; Fe/TIBC, iron/total iron-binding capacity; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBsAb, hepatitis B surface antibody; HBeAg, hepatitis B eAntigen; HCV Ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LFTs, liver function tests; SPEP, serum protein electrophoresis; PT/INR, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio; RUQ U/S, right upper quadrant ultrasound; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Abnormal liver enzymes

The University of Michigan classified abnormal liver enzymes into two broad categories: cholestatic (alkaline phosphatase significantly more elevated than AST/ALT) and hepatitic (AST/ALT <5X upper limit of normal, AST/ALT >5X upper limit normal). All proposed workup met consensus criteria except for serum protein electrophoresis, which was eliminated. Experts proposed the addition of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, alpha-1 antitrypsin, iron studies and cessation of potential offending medications to this workup, and all were retained. There were differences between PCPs (median 3) and GIs (median 4) regarding anti-smooth muscle antibody.

Hepatitis B

The panel endorsed all of the originally proposed workup for hepatitis B including CBC, liver function tests (LFTs), prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR), hepatitis B eAntigen (HBeAg), anti-HBeAg, hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA, screening spouse and family members, decrease/abstain from alcohol, hepatitis A virus (HAV) vaccination, and advise on precautions to prevent transmission. Experts also proposed the following additional tests: human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), ultrasound and hepatitis C virus antibody (HCV Ab). All tests were highly rated with nine of the tests ranking at a level of 4 or more by 100% of participants.

Hepatitis C

The original proposed workup was CBC, LFTs, PT/INR, genotype, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), iron/total iron binding capacity (Fe/TIBC) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)/ultrasound in the presence of cirrhosis. Additional proposed workup was decrease/abstain from alcohol, HAV and HBV vaccination, and advice on precautions to prevent transmission. All workup for hepatitis C met consensus criteria except for Fe/TIBC, which was eliminated. HCV RNA, HIV and percentage of iron saturation were additional proposed tests. HIV and HCV RNA were retained, but the percentage of iron saturation did not meet consensus criteria. Percent iron scored a median of 3 among PCPs and a median score of 4 among GIs.

Liver mass and fatty liver disease

All initial recommendations for these two diagnoses scored highly among panellists. All exceeded the 70% needed to meet consensus criteria. All labs were given a 4 or 5 by all panellists except for CMP (91%) for liver mass and PT/INR (91%) and CBC (82%) for fatty liver disease. There were no additional tests proposed.

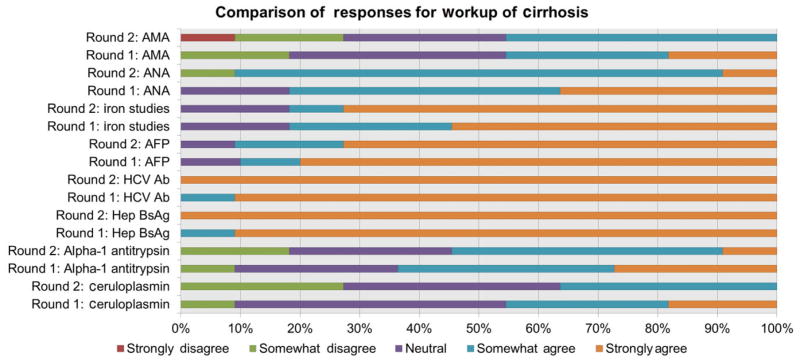

Cirrhosis

The original proposed workup included HBsAg, HCV Ab, AFP, iron studies, anti-nuclear antibody, AMA, ceruloplasmin and alpha-1 antitrypsin. All proposed studies were retained except alpha-1 antitrypsin, AMA and ceruloplasmin. Figure 1 shows the changes in responses for a given diagnostic test from one round to the subsequent round. For example, during round 1 rankings for HBsAg, panellists ranked either agree [4] or strongly agree [5]. By round 2, 100% participants all ranked strongly agree. On the other hand, in round 1, at least 10% participants had ranked AMA, alpha-1 antitrypsin and ceruloplasmin as strongly agree. By round 2, participants changed their responses such that a smaller proportion of participants ranked strongly agree. When looking at median scores by doctor specialty, there was some disagreement among PCPs and GIs among the following labs: iron studies (PCP median 3; GI median 5), AMA (PCP median 4; GI median 3), alpha-1 antitrypsin (PCP median score 3, GI median score 4).

Figure 1.

This figure depicts the changes in responses from round 1 to round 2 for the proposed laboratory workup for cirrhosis.

Discussion

In this study, we developed local consensus guidelines on the essential pre-referral workup – including laboratory testing, clinical criteria and therapeutic trials – on 13 different gastrointestinal and liver conditions among an expert panel of primary care doctors and gastroenterologists. We believe if utilized in practice that these components have the potential to lead to fewer yet higher quality referrals as well as a more productive initial consultation between the patient and the specialist. For the PCP, a referral can be avoided or deferred if a certain intervention was effective (an adequate PPI trial for reflux) or if a positive test could be acted upon without further need for specialist workup (e.g. improvement off lactose in the workup of abdominal bloating). For the specialist and the patient, having information prior to the visit (e.g. HCV genotype to help guide treatment options) will lead to a more efficient visit. For the patient, a conclusive study (e.g. direct referral for colonoscopy for ongoing rectal bleeding) will result in timely and efficient care. Within our medical centre across three unique hospital delivery systems, we demonstrated agreement between primary care doctors and specialists. We believe our findings to be generalizable to the majority of integrated delivery systems with primary and specialty care.

Our study is unique in that we recruited both primary care doctors and specialists to define our guidelines. Collaboration and communication with the primary care doctor is critical in order to improve care quality and efficiency. We believe the consensus achieved between primary care and specialty care should also support adherence to the guidelines, potentially limiting overuse/misuse of laboratory and/or diagnostic testing.

While we did achieve overall consensus, we did note some disagreement among PCPs and specialists among certain laboratory tests. In the majority of cases, PCPs appeared to indicate lower importance on items compared with GIs. The reasons for this are unclear and our sample size is too small to make any conclusions regarding differences between PCP and specialist responses as well as any difference in responses between sites. Our group plans to address these differences via PCP-specialist co-management conferences where we will discuss doctor attitudes with regards to the appropriateness of the laboratory workup to these diagnoses. For example, IgA TTG scored lower among PCPS than GIs in the workup of iron deficiency anaemia. Our conference would address doctor reasons for either ordering or not ordering the test and whether or not IgATTG testing is appropriate. Buy-in from the PCP is extremely important because the PCP is ultimately responsible for the tests that are ordered.At our institution, the PCP is able to get a hold of the specialist in the event that specialty care is delayed or if the patient decided to forgo seeing a specialist.

These local guidelines represent an important first step in defining the components of an appropriate referral. This is the first published study, to our knowledge, to use the Delphi method to optimize the pre-referral workup for GI and hepatology. We believe that using a Delphi approach in such an area of study where specific evidence is lacking regarding PCP referrals to GI is a strength of this study. However, our study is not without limitations. The study included only a fraction of all doctors at our centre, and all doctors were part of a single academic medical centre. It is quite possible that the responses of the panel do not fully represent the opinions of all faculty. Furthermore, there may be differences across other faculty practices as well as differences between academic centres and community practices. For example, while our workup of abdominal bloating differed from that of University of Michigan, we believe this likely reflects different management styles between the two locations and may also reflect and/or accommodate different disease prevalence and population differences. Development of referral guidelines at a national level may help establish a better baseline, but our study suggests that when strong evidence is lacking for specific recommendations that a local tailoring process will likely be necessary to achieve maximal adoption.

In summary, we believe this is the first study to discuss ‘how’ to refer for some of the most common reasons for GI-related visits [1]. This study fills a current gap in knowledge where there are currently no standards by which to refer, and could serve a proof of concept for local consensus-building initiatives at other centres, as well as towards a national consensus. Filling this gap, in turn, can lead to more efficient initial specialty visits, including timelier diagnosis and treatment for the patient. Suggested next steps include gathering input from patient stakeholders as well as a programme evaluation. Patient stakeholders could give an opinion on therapeutic trials versus diagnostic tests in cases where the evidence base is insufficient. An evaluation post-implementation of such referral guidelines would include assessment of patient uptake and follow through with specialty visit. How best to implement these guidelines in practice and evaluate the impact of these guidelines on care efficiency are crucial to improving health care value in patients with chronic GI and liver disease.

References

- 1.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179–87. e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett ML, Song Z, Landon BE. Trends in physician referrals in the United States, 1999–2009. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172(2):163–170. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrotra A, Forrest CB, Lin CY. Dropping the baton: specialty referrals in the United States. The Milbank Quarterly. 2011;89(1):39–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akbari A, Mayhew A, Al-Alawi MA, et al. Interventions to improve outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(4):CD005471. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005471.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi TK, Sittig DF, Franklin M, Sussman AJ, Fairchild DG, Bates DW. Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(9):626–631. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McPhee SJ, Lo B, Saika GY, Meltzer R. How good is communication between primary care physicians and subspecialty consultants? Archives of Internal Medicine. 1984;144(6):1265–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenkins RM. Quality of general practitioner referrals to outpatient departments: assessment by specialists and a general practitioner. The British Journal of General Practice. 1993;43(368):111–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Malley AS, Reschovsky JD. Referral and consultation communication between primary care and specialist physicians: finding common ground. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(1):56–65. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh H, Esquivel A, Sittig DF, et al. Follow-up actions on electronic referral communication in a multispecialty outpatient setting. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;26(1):64–69. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1501-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stille CJ, McLaughlin TJ, Primack WA, Mazor KM, Wasserman RC. Determinants and impact of generalist-specialist communication about pediatric outpatient referrals. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1341–1349. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Tetroe J. Implementing clinical guidelines: current evidence and future implications. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2004;24(Suppl 1):S31–S37. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340240506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rescher N. Predicting the Future. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1998. p. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.University of Michigan. [last accessed 1 June 2015];University of Michigan Consult Request Guidelines. 2013 Available at: http://med.umich.edu/umhs/health-providers/consult_request_guidelines.html.