Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Medications for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) may affect survival. However, studies often include limited follow-up and do not account for selection bias in treatment allocation. Using a large longitudinal database, we examined the association between prednisone use and mortality in RA, and whether this risk was modified with concomitant disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) use, after controlling for propensity for treatment with prednisone and individual DMARDs.

METHODS

In a prospective study of 5,626 patients with RA followed for up to 25 years, we determined the risk of death associated with prednisone use alone and combined treatment of prednisone with methotrexate or sulfasalazine. We used the random forest method to generate propensity scores for prednisone use and each DMARD at study entry and during follow-up. Mortality risks were estimated using multivariate Cox models that included propensity scores.

RESULTS

During follow-up (median 4.97 years), 666 patients (11.8%) died. In a multivariate, propensity-adjusted model, prednisone use was associated with an increased risk of death (HR 2.83 [95% CI 1.03, 7.76]). However, there was a significant interaction between prednisone use and methotrexate use (p=0.03), so that risk was attenuated when patients were treated with both medications (HR 0.99 [95% CI 0.18, 5.36]). However, combination treatment also weakened the protective association of methotrexate with mortality. Results were similar for sulfasalazine.

CONCLUSION

Prednisone use was associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality in patients with RA. This association was mitigated by concomitant DMARD use, but combined treatment also negated the previously reported beneficial association of methotrexate with survival in RA.

Introduction

Glucocorticoids have been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA) since the 1950’s, but their role in the management of RA remains a matter of debate. Although glucocorticoids reduce inflammation and arthritis symptoms, improve physical function, and appear to have disease-modifying properties (1), their chronic use is associated with numerous potentially life-threatening side effects and comorbidities. In addition, prednisone use has been associated with an increased risk of death in patients with RA, with mortality risk approximately twice that of patients not treated with prednisone (2, 3, 4). However, because prednisone is often used to treat patients with more severe RA, it is still unclear if the increased mortality risk is due to the medication or related to its use by sicker patients (3).

We examined the association between prednisone use and mortality in a 25-year observational study of patients with RA, and used two different statistical approaches to adjust for potential bias in treatment selection. Additionally, because prednisone is commonly used in combination with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and because the use of some DMARDs, such as methotrexate, has been associated with lower mortality risks (5), we sought to determine if concomitant DMARD use modified the mortality risk associated with prednisone use. We hypothesized that prednisone use would be associated with an increased risk of mortality, and that this increased risk would be reduced by the concomitant use of DMARDs.

Materials and Methods

This prospective, longitudinal observational study assessed changes in the treatment, costs, and outcomes of an open cohort of RA patients over 25 years of enrollment. Adults with RA as described by the 1987 ACR criteria (6) were recruited from ten North American rheumatology practices (seven university centers and three community practices) to participate in the Arthritis, Rheumatism, and Aging Medical Information Systems (ARAMIS) study between July 1981 and December 2006. The RA diagnosis was verified by the study’s rheumatologists or by medical record review (6% of cases). Patients completed a Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) biannually by mail; this validated instrument included the HAQ-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) and measures of pain, global health, medication use, resource utilization, comorbidities, and selected health behaviors (7). Arthritis medication data were collected by patient report on each questionnaire and updated every six months. Medication dose and smoking status data were not available. Participants were followed from study entry to death, withdrawal from the study, or December 2006. Information on death was obtained from family members, physicians, and the U.S. National Death Index, a government-run death database. Each institution’s institutional review board approved the study; all participants provided written informed consent.

The study’s statistical methods were previously described in detail (5). In brief, we estimated the relationship between prednisone use and mortality using Cox regression models, with prednisone use as a time-varying covariate. Patients who were lost to follow-upor were known to have died more than one year after the last questionnaire were treated as censored observations in the mortality analysis. In multivariate models, we included the time-invariant covariates: age, gender, ethnicity, education level, and duration of RA at entry. Time-varying covariates included body mass index (BMI), HAQ-DI score, pain score, rheumatologist visit (yes/no), indicator variables for ten comorbid conditions, and indicator variables for seven anti-rheumatic medications (methotrexate, sulfasalazine, intramuscular gold, other DMARDs, anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha medications, non-selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and COX-2 selective NSAIDs). The ten comorbid conditions were hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, lung disease, diabetes, cancer, gastrointestinal disease, liver disease, and infections. As the BMI and HAQ-DI associations with death were nonlinear over time, they were modeled using restricted cubic splines. Values for all but the demographic characteristics were time-varying and updated every six months. Missing data at entry was imputed using the random forest method; for all subsequent missing data, last value carried forward method was employed. Models included study site and year of study entry as strata to account for potential cohort effects.

To accurately assess the association between prednisone use and mortality, our statistical models accounted for the possibility that factors associated with prednisone treatment may also be mortality risk factors. We used two statistical methods, propensity scores (8) and inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) (9), to account for treatment selection bias. A propensity score is a predictor that estimates the probability that a specific patient is likely to be prescribed a medication, based upon the characteristics and prescription patterns of all the patients in the study. IPTW uses the inverse of this probability to weight each observation, in order to “level the playing field” regarding the likelihood of each subject receiving the drug. This is used for the time-dependent treatments and the time dependent confounders seen in this sample over the 25 years of study. The propensity scores for each medication were calculated by fitting a random forest model (10) with medication use (yes/no) as the outcome and all demographic and clinical characteristics at each time point as predictors, and the predicted probability for each individual at each time point to take the medication based on the fitted model was used as their propensity score. Random forests are an ensemble of a set of decision trees, each fit on a bootstrapped resample of the original data. Predictions from each decision tree are based on the so-called out-of-bag set, i.e. the set of data points not used for training a tree. The overall prediction from the random forest is the average prediction for each observation across all the generated trees. Each random forest was based on 500 classification trees. Random forests are scalable and accurate for prediction problems and have been recommended to perform more robust, model-free propensity estimations (11). We then examined the relationship between prednisone use in combination with methotrexate and with sulfasalazine and mortality to determine if combination therapy with these medications and prednisone altered the risk of death associated with prednisone use. These medications were selected because they were the most commonly used DMARDs during the time frame of this study. We tested the interaction between prednisone use and methotrexate use, and between prednisone use and sulfasalazine use, in separate models that included covariates noted above, as well as propensity scores for prednisone and for each DMARD. These models provided estimates of the hazard ratio associated with prednisone use alone, with the DMARD alone, and with combined treatment, compared to patients not treated with either prednisone or the DMARD under consideration.

Analyses were completed using R version 2.15.1, along with the packages survival (v. 2.36-14) and randomForest (v. 4.6-6).

Results

Characteristics of the 5626 patients are shown in Table 1. Patients were primarily middle-aged, female, and Caucasian, with a median RA duration of 7.1 years at study entry. The median follow-up was 4.97 years. Over 38,130 patient-years of observation, 3496 (62%) patients received prednisone, 2920 (52%) received MTX, and 761 (14%) received sulfasalazine. The median duration of use of prednisone was 2 years (mean 3.57 years). Information on prednisone dosage was available in 5513 patients (98%) at study entry, with median dose of 5 mg daily (Interquartile (25, 75) range (IQR) of 5 mg, 10 mg) in the 2200 (39%) taking prednisone. Of 67,947 completed questionnaires during the observation period, median prednisone daily dosing was reported in 99% of encounters, with a median daily dose of 5 mg (IQR 4 mg, 8 mg).

Table 1.

Summary statistics at questionnaire cycle of entry into ARAMIS

| Variable | Never on Prednisone | Ever on Prednisone | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 38% (N=2130) | 62% (N=3496) | (N=5626) | |

| Age | 57.3+/−14.3 | 56.9+/−13.5 | 57.1+/−13.8 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 26% ( 553) | 24% ( 834) | 25% (1387) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-white | 11% ( 224) | 10% ( 357) | 10% ( 581) |

| Education level in years | 12.61+/− 2.76 | 12.75+/− 2.58 | 12.70+/− 2.65 |

| Disease duration | 10.54+/−10.60 | 10.61+/−10.05 | 10.58+/−10.26 |

| BMI | 26.50+/− 5.17 | 26.52+/− 5.30 | 26.51+/− 5.25 |

| Rheumatology consult | |||

| Yes | 63% (1352) | 73% (2569) | 70% (3921) |

| HAQ-DI score | 0.976+/−0.762 | 1.234+/−0.779 | 1.136+/−0.782 |

| Pain score | 1.119+/−0.774 | 1.333+/−0.781 | 1.252+/−0.785 |

| Mean duration of observation | 5.67+/− 5.56 | 7.46+/− 6.04 | 6.78+/− 5.93 |

| Hypertension | 18% ( 387) | 21% ( 732) | 20% (1119) |

| Coronary disease | 2% ( 53) | 4% ( 145) | 4% ( 198) |

| Lung disease | 8% ( 180) | 12% ( 410) | 10% ( 590) |

| Intestinal disease | 11% ( 235) | 17% ( 595) | 15% ( 830) |

| Liver disease | 1% ( 15) | 1% ( 33) | 1% ( 48) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4% ( 92) | 4% ( 135) | 4% ( 227) |

| Cancer | 4% ( 75) | 4% ( 129) | 4% ( 204) |

| Congestive heart failure | 0% ( 10) | 1% ( 34) | 1% ( 44) |

| Stroke | 1% ( 20) | 1% ( 36) | 1% ( 56) |

| Infections | 4% ( 93) | 13% ( 451) | 10% ( 544) |

| Mean no. of comorbidities | 0.915+/−1.288 | 1.260+/−1.432 | 1.129+/−1.389 |

| Prednisone | 0% ( 0) | 64% (2245) | 40% (2245) |

| MTX | 20% ( 436) | 32% (1113) | 28% (1549) |

| Sulfasalazine | 3% ( 59) | 4% ( 155) | 4% ( 214) |

| Other DMARDs* | 32% ( 682) | 46% (1595) | 40% (2277) |

| TNF inhibitors | 2% ( 39) | 2% ( 66) | 2% ( 105) |

| NSAIDs | 62% (1331) | 65% (2273) | 64% (3604) |

| COX2 inhibitors | 2% ( 53) | 2% (86) | 2% ( 139) |

excluding methotrexate and sulfasalazine

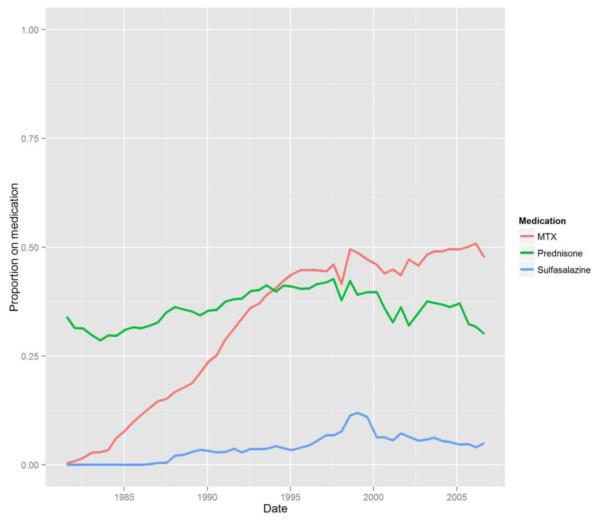

Compared with those not taking prednisone, prednisone users had higher HAQ-DI and pain scores, more comorbidities, were more likely to be treated with DMARDs, and were more likely to have seen a rheumatologist at study entry. Over the duration of the study, the prevalence of prednisone use was relatively stable at 40-50%, use of MTX increased, and use of sulfasalazine decreased (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of prednisone, methotrexate and sulfasalazine use in ARAMIS over time (1981-2005)

A total of 666 (11.8%) patients died during observation. Another 4599 patients were lost to follow-up, and 361 died >1year after last questionnaire. In the univariate time-varying Cox regression model, prednisone use was associated with an increased risk of death (hazard ratio [HR] 2.23, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.91, 2.60). In the multivariate regression model without propensity score or IPTW adjustment, the hazard for death with prednisone use was 1.73 (95% CI 1.46, 2.07). With propensity score adjustment, the hazard for death was 2.83 (95% CI 1.03, 7.76). Using IPTW, prednisone use remained associated with increased mortality (HR1.75, 95% CI 1.49, 2.04). Because the use of many treatmetns may have changed over the course of the study, we also stratified the cohort into early and later subsets, whom would be expected to have more homogeneity in other treatments. The associations between prednisone use and mortality were similar in the subset of patients who entered the study before 1995 and those who entered in 1995 or later.Stratifying the study population to those entering the study before and after 1995, to maintain some homogeneity of medications patients might have received, did not alter the relationship between prednisone use and mortality.

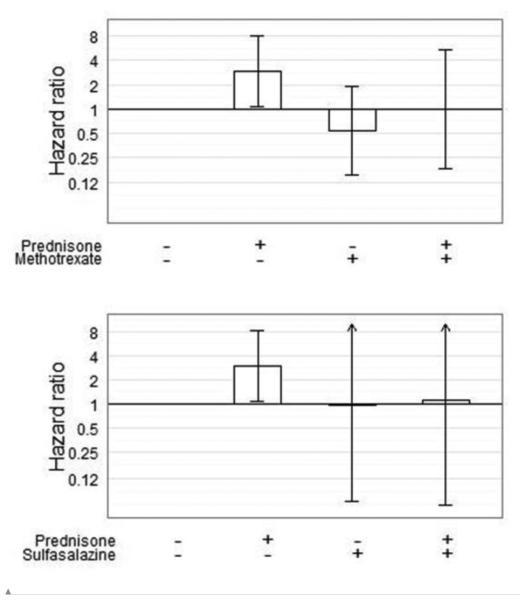

In examination of whether the mortality risk associated with prednisone use was modified by concomitant DMARD use, we found a significant interaction between prednisone use and methotrexate use in relation to mortality (p = 0.03). In this model, patients who were treated with prednisone alone had an increased risk of mortality (HR = 2.95, 95% CI 1.07, 8.10), but those who were treated with both prednisone and methotrexate had no greater mortality risk than those treated with neither medication (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.18-5.36) (Figure 2). Use of sulfasalazine also attenuated the mortality risk associated with prednisone use (HR 1.09, 95% CI 0.06, 19.80), compared with prednisone alone (HR 2.99, 95% CI 1.09, 8.17). The interaction between these medications was statistically significant (p = 0.04).

Figure 2.

Hazard for death associated with prednisone monotherapy and in combination with methotrexate and sulfasalazine. Cox time-varying multivariable regression model, adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, education level, duration of RA at study entry, BMI, HAQ Disability Index, pain, rheumatology visit (y/n), NSAIDs, DMARDs (excluding the one under study), TNF inhibitors, COX-2 inhibitors, comorbidities and both prednisone and DMARD baseline and time-dependent propensities, stratified by time of study entry and location.

Discussion

In this 25-year study, the use of prednisone was associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality in patients with RA, even after accounting for potential bias in treatment selection using either propensity score or IPTW adjustment. This relationship was mitigated by concomitant use of methotrexate or sulfasalazine. Others have documented the deleterious relationship between prednisone use and survival in RA. (4, 12, 13, 14) The consistent increase in risk reported in these studies supports a true association, but because most of these studies did not adjust for the possibility of bias in treatment selection, the magnitude of this risk is still uncertain. The patients in our study who received prednisone had more severe RA, with higher HAQ-DI, more comorbid conditions, and higher prevalence of DMARD use. Our cohort was similar in these respects to other cohorts that examined associations with prednisone use among patients with RA. (3)

Our results indicate an increased risk of mortality with prednisone use even when accounting for treatment selection. Both adjustment methods, namely propensity scores and IPTW, resulted in the same conclusion, which lends support to the validity of the results. Davis and colleagues suggested that the association of prednisone use with mortality in RA may depend on dosing, duration, or cumulative exposure (15). Our dosing data indicates that daily prednisone use was low (median 5 mg daily).

However, our analysis revealed that the mortality risk associated with prednisone use was modified by the use of other DMARDs, particularly methotrexate and sulfasalazine. When used in combination with these DMARDs, prednisone use was not associated with an increased mortality risk. Reasons for this moderating effect are unclear. Perhaps the more effective anti-inflammatory effects of combination therapy allowed for lower prednisone doses, thereby reducing the mortality risks. Alternatively, perhaps the DMARDs offset adverse effects of prednisone treatment on comorbid conditions. For example, the detrimental impact of prednisone on cardiovascular risk via its effects on blood pressure and lipids may be reduced by the cardioprotective effects of methotrexate, as previously suggested by Choi et al. (8). We also previously have described potential mechanisms by which methotrexate may attenuate the increase in cardiovascular risk observed in RA (5). It is also possible that DMARD use was a marker of better quality of care or of more informed and adherent patients and that these factors were mainly responsible for the reduced mortality risks that were observed. Although the models adjusted for rheumatologist visits and patient’s level of education, the associations with DMARD use may be due to residual confounding by quality of medical care, patient socioeconomic status, or related factors. Importantly, combined use of prednisone and methotrexate also negated the survival benefit associated with methotrexate use alone. While adverse effects of sulfasalazine, particularly blood dyscrasias, can be fatal, their impact on mortality rates has not been described in large RA cohorts.

Our study has limitations inherent to observational studies with data collected by self-report. We had no physician confirmation of medication use, and prednisone dosing was not available. We also did not have data on medication use patterns prior to study enrollment. Information on smoking habits and marital status was not collected systematically; therefore these important covariates were not included in analyses. Bias due to unobserved confounders is possible. Finally, given the years when most of the follow-up occurred, we had insufficient data on patients treated with biologic therapies, and therefore cannot determine the potential impact of these medications on mortality in this cohort. We also could not account for improvements in health care that occurred over the extensive observation period which quite likely influenced survival.

Strengths of this study include the size and 25-year duration of observation of our cohort, and the scope of variables available for inclusion in the regression models. Our analyses included two approaches to address bias in treatment selection with consistent results using both of these approaches.

In conclusion, we have shown that prednisone use is associated with increased mortality in RA. The strength of this association is somewhat increased when propensity for prednisone use is taken into consideration. We have demonstrated that the hazard for death with prednisone is reduced when it is combined with selected DMARDs, indicating that combination therapy with DMARDs offsets the adverse effects of prednisone specifically on risk of death. While our findings suggest that combination therapy may be relatively safe regarding mortality risk, the well-known adverse effects of long term low dose prednisone still favor limited use of this medication for bridge therapy. We also have noted that the beneficial effects of methotrexate on mortality risk are reduced when combined with prednisone, again suggesting that prednisone should be used sparingly in RA patients taking methotrexate. Finally, our results highlight the importance of examining the relationship between combination therapy and outcomes of interest, as the complex clinical effects of medications may be offset by one another when used together in daily practice. Areas of future interest include the impact of biologic therapies on these relationships.

Significance and Innovations.

Leveraged a large, longitudinal cohort of over 5000 RA patients to demonstrate increased mortality associated with prednisone use in RA using propensity score for corticosteroid use.

Key finding: negation of previously described methotrexate-related increase in survival when prednisone is prescribed in combination with methotrexate.

Acknowledgments

Source of support:

Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, grant AR-43584

Footnotes

No financial support or other benefits from commercial sources have been received for the work reported in this manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Kirwan JR. Arthritis and Rheumatism Council Low Dose Glucocorticoid Study Group. The effect of glucocorticoids on joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:142–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507203330302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mikuls TR, Fay BT, Michaud K, et al. Associations of disease activity and treatments with mortality in men with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the VARA registry. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:101–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caplan L, Wolfe F, Russell AS, et al. Corticosteroid use in rheumatoid arthritis: prevalence, predictors, correlates, and outcomes. J Rheum. 2007;34:696–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Rincón I, Battafarano DF, Restrepo JF, et al. Glucocorticoid dose thresholds associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Arth Rheum. 2014;66:264–272. doi: 10.1002/art.38210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wasko MCM, Dasgupta A, Hubert H, et al. Propensity-adjusted association of methotrexate with overall survival in rheumatoid arthritis. Arth Rheum. 2013;65:334–42. doi: 10.1002/art.37723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arth Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY. The dimensions of health outcomes: the health assessment questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheum. 1982;9:789–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi HK, Hernan MA, Seeger JD, et al. Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359:1173–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugihara M. Survival analysis using inverse probability of treatment weighted methods based on the generalized propensity score. Pharm Stat. 2010;9:21–34. doi: 10.1002/pst.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee BK, Lessler J, Stuart EA. Improving propensity score weighting using machine learning. Stat Med. 2010;29(3):337–46. doi: 10.1002/sim.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saag KG, Koehnke R, Caldwell JR, et al. Low dose long-term corticosteroid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: an analysis of serious adverse events. Am J Med. 1994;96:115–23. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bollet AJ, Black R, Bunim JJ. Major undesirable side-effects resulting from prednisolone and prednisone. JAMA. 1955;158:459–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02960060017005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Truhan AP, Ahmed AR. Corticosteroids: a review with emphasis on complications of prolonged systemic therapy. Ann Allergy. 1989;62:375–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis John M, Maradit-Kremers Hilal, Gabriel Sherine E. Use of low-dose glucocorticoids and the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: what is the true direction of effect? J Rheum. 2005;32:1856–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]