Abstract

Current guidelines recommend completion axillary lymphnode dissection (ALND) when sentinel lymphnode (SLN) contains metastatic tumor deposit. In consequent ALND sentinel node is the only node involved by tumor in 40–70 % of cases. Recent studies demonstrate the oncologic safety of omitting completion ALND in low risk patients. Several nomograms (MSKCC, Stanford, MD Anderson score, Tenon score) had been developed in predicting the likelihood of additional nodes metastatic involvement. We evaluated accuracy of MSKCC nomogram and other clinicopathologic variables associated with additional lymph node metastasis in our patients. A total of 334 patients with primary breast cancer patients underwent SLN biopsy during the period Jan 2007 to June 2014. Clinicopathologic variables were prospectively collected. Completion ALND was done in 64 patients who had tumor deposit in SLN. The discriminatory accuracy of nomogram was analyzed using Area under Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC). SLN was the only node involved with tumor in 69 % (44/64) of our patients. Additional lymph node metastasis was seen in 31 % (20/64). On univariate analysis, extracapsular infiltration in sentinel node and multiple sentinel nodes positivity were significantly associated (p < 0.05) with additional lymph node metastasis in the axilla. Area under ROC curve for nomogram was 0.58 suggesting poor performance of the nomogram in predicting NSLN involvement. Sentinel nodes are the only nodes to be involved by tumor in 70 % of the patients. Our findings indicate that multiple sentinel node positivity and extra-capsular invasion in sentinel node significantly predicted the likelihood of additional nodal metastasis. MSKCC nomogram did not reliably predict the involvement of additional nodal metastasis in our study population.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Sentinel node positive, Non-sentinel node metastasis, MSKCC nomogram

Introduction

Axillary clearance provides information on the extent of axillary nodal involvement which continues to be a reliable indicator of prognosis and staging in breast cancer patients. However, axillary clearance is associated with morbidity including seroma, lymphedema, and shoulder dysfunction in 6 to 30 % of patients [1]. In the 1990s Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) was developed and began to be accepted as an alternative for staging axilla in clinically node negative patients [2]. SLNB has now become the standard of care in clinically node negative breast cancer patients.

Subsequent studies analyzing the SLNB series noted that in 40–70 % of patients sentinel nodes (SLN) are the only nodes to be involved with tumor without any additional non-sentinel node (NSLN) involvement [3]. These individuals undergo ALND without any therapeutic benefit or any additional prognostic information obtained and exposing them to the potential complications of axillary dissection. Identification of the patients with a low probability of NSLN metastasis can spare them of the morbidity associated with ALND. Involvement of NSLN is dependent on primary tumor and sentinel node characteristics and several authors have devised nomograms and scoring systems (incorporating tumor and sentinel variables) to predict the probability of NSLN metastasis. The most popular ones are Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) nomogram [4], Cambridge nomogram [5], Stanford nomogram [6], Tenon score [7] and MD Anderson cancer center score [8]. Of these MSKCC nomogram remains the most validated nomogram in different settings [9–16]. The results have been varying in different series but in general appear to be accurate.

In the present study we aim to assess the incidence of NSLN involvement in our patients and to identify the risk factors associated with NSLN metastasis (NSLNM). We also evaluated the accuracy of MSKCC nomogram in predicting the NSLN metastasis in our cohort of patients.

Materials and Methods

We reviewed our prospectively collected database of patients treated at our center between Jan 2007 and July 2014. A total of 334 patients with clinically T1-T3 N0 tumors underwent SLNB during this period. Axilla was considered negative by clinical examination and axillary ultrasound. All patients who underwent completion ALND after SLN positivity were included in the study. Data collected included patients characteristics, tumor characteristics [size, histologic type, grade of the lesion, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), multifocality/multicentricity, estrogen and progesterone receptor (ER/PR) status, HER2-nu status and characteristics of the SLNs and other axillary lymph nodes (number of SLNs and NSLNs involved, size of SLNs- micro/macro mets, extracapsular invasion in SLN and NSLN).

Sentinel Node Localization

Sentinel nodes were localized using a combined technique of radiocolloid and blue dye injection. Technetium 99 sulphur colloid was injected in sub-areolar region 2 to 6 h prior to surgery. At time of surgery, prior to incision 2 ml of methylene blue was injected in sub-areolar plane followed by 5 min breast massage at site of injection. A hand held gamma probe was used to guide the site of incision and dissection in axilla. Nodes with isotope count greater than 10 % of count in injection site are labelled hot nodes. All hot, blue, hot and blue nodes are dissected out and submitted for frozen section. In addition any suspicious enlarged nodes were also removed and submitted for intra-operative frozen section analysis. If sentinel nodes were found to be positive for tumor, axillary dissection was performed at same sitting. The nodes obtained from axillary clearance were submitted for routine histopathology analysis.

Statistical Analysis and MSKCC Nomogram Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P value was considered significant when less than 0.05.The online version of MSKCC nomogram (available in http://nomograms.mskcc.org/Breast/BreastAdditionalNonSLNMetastasesPage.aspx) was used to calculate the predicted probability of NSLN metastasis. The probability is calculated based on eight variables namely tumor size, tumor type and grade, number of SLN positive, number of SLN negative, method of detection of SLN, LVI presence, multifocality, ER receptor status. The clinico-pathological variables were fed into online calculator and predicted probability (percentage score) was obtained for each individual patient. A receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed and Area under curve (AUC) was calculated to assess the discriminative accuracy of nomogram. In general it is accepted that AUC values of 0.7 to 0.8 represent considerable discrimination and AUC > 0.8 represents excellent discrimination.

Results

Of 334 patients who underwent SLNB during the study period, 70 (20.5 %) had SLN involved by tumor. Six patients had SLN metastasis identified in final HPE after a negative report on frozen section (false negative). They did not undergo ALND subsequently and axilla was included in the radiation field. Rest of the 64 patients who underwent ALND constituted the study group. SLN identification rate was 100 % and false negative rate was 8.5 % (6/70–3 macro metastasis; 2 micro metastasis and one isolated tumor cluster cells positive detected by immunohistochemistry). The median patient age was 51 and median tumor size was 2.5 cms (range 1.2 to 6.5 cms). The median number of sentinel nodes removed was 3 (range 1–10) and median number of positive SLNs was 1 (range 1–4). Eighty percent (n = 51) of SLN positive cases had tumor involvement limited to single sentinel node. The median number of nodes excised at ALND was 18 (range 13–40). In final HPE after completion ALND it was observed that only sentinel nodes were involved without any additional nodal metastasis in 68.8 % (n = 44) of patients. NSLN was found to be metastatic in 20 of 64 patients (31.2 %) and more than half of them (11/20; 55 %) had only one NSLN involved by tumor. The median number of metastatic NSLN was 1 (range 1–6).

By univariate analysis extra-capsular invasion in sentinel node (p = 0.0002) and more than one node positive in SLNB (p = 0.04) were statistically significantly associated with additional NSLN metastasis. Ratio of SLN positive by SLN harvested when greater than 0.5 (42 % in ratio > 0.5 vs 21 % in ratio < 0.5) and sentinel macro-metastasis (0 % in micro-metastasis vs. 32.7 % in macro-metastasis) showed a trend towards NSLN positivity though not statistically significant. Other factors like T size, grade of lesion, multifocality/multicentricity, LVI and ER/PR status were not statistically significantly associated with NSLN metastasis in this study. On multivariate analysis (binary logistic regression analysis) extracapsular invasion in SLN (p = 0.0001, Odds Ratio = 11.3) was significantly associated with NSLN metastasis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association of clinicopathological variables with non-sentinel metastasis

| Variable (total n) | Non sentinel positive (n = 20) | Non-sentinel negative (n = 44) |

P Value Uni variate analysis |

P value Multivariate analysis (OR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 tumors (n = 22) | 8(36.3 %) | 14(63.7 %) | ||

| T2 tumors (n = 42) | 12(28.6 %) | 30(71.4 %) | 0.523 | NS |

| Grade | ||||

| Low and intermediate (n = 36) | 12(33.3 %) | 24(66.7 %) | ||

| High (n = 24) | 5(20.8 %) | 19(79.2 %) | 0.293 | NS |

| Histology | ||||

| IDC [n = 60] | 17 [28.3 %] | 43 [71.7 %] | ||

| ILC [n = 4] | 3 [75 %] | 1 [25 %] | 0.087 | NS |

| Multifocal | ||||

| Yes [n = 6] | 0 | 6 [100 %] | ||

| No [n = 58] | 20 [34.5 %] | 38 [65.5 %] | 0.094 | NS |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||

| Yes [n = 11] | 3 [27 %] | 8 [73 %] | ||

| No [n = 53] | 17 [32 %] | 36 [67.9 %] | 0.530 | NS |

| Extra-capsular invasion | ||||

| Yes [n = 15] | 11 [73.3 %] | 4 [26.7 %] | ||

| No [n = 49] | 9 [18.3 %] | 40 [81.7 %] | 0 .002 | 0.0001 (11.3) |

| ER positive | ||||

| Yes [n = 53] | 18 [33.9 %] | 35 [66.1 %] | ||

| No [n = 11] | 2 [19 %] | 9 [81 %] | 0.258 | NS |

| Sentinel | ||||

| Only 1 node + [n = 51] | 13 [25.6 %] | 38 [74.5 %] | ||

| >1 node + [n = 13] | 7 [53.8 %] | 6 [46.2 %] | 0.04 | 0.99 |

| Size of sentinel mets | ||||

| Micro-mets | 0 [0 %] | 3 [100 %] | ||

| Macro-mets | 20 [32.8 %] | 41 [67.2 %] | 0.232 | 0.99 |

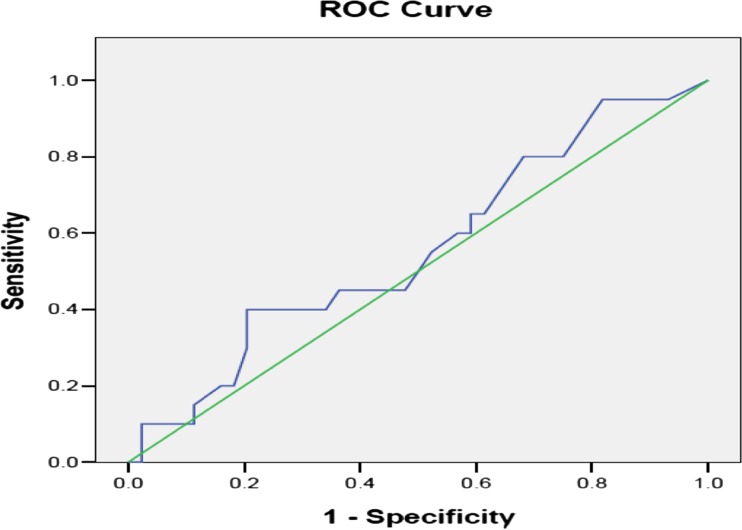

The overall clinicopathological details of the original MSKCC prospective series (n = 373) and our study group (n = 64) are compared in Table 2. Our cohort had larger tumor size (p = 0.0002), lower incidence of multifocal and LVI + tumors (p = 0.0002 and 0.001 respectively) and higher number of negative SLN (p = 0.03). Differences between other variables were not statistically significant. The predicted probabilities of NSLN metastasis in all patients ranged between 20 and 75 % with a mean of 40 %. The mean predicted probability in NSLN free and NSLN metastatic group were 38.9 and 42.1 % respectively. The predictive accuracy of MSKCC nomogram measured by area under ROC curve was AUC = 0.558 (95 % CI 0.406 to 0.710) (Fig. 1). In 22 patients with T1 tumors the AUC was 0.60 (95 % CI = 0.35–0.86) and in 42 T2 tumors AUC was 0.55 (95 % CI = 0.38–0.73).

Table 2.

Comparing original MSKCC prospective group with our study group

| Variables | MSKCC n = 373 | Our study n = 64 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <50 | 157(42.1) | 28 (43.7) | |

| >50 | 216(57.9) | 36(56.3) | 0.321 |

| Tumor size | |||

| <5 mm | 13(3.5) | 0(0) | |

| 5 to 10 mm | 49(13.1) | 0(0) | |

| 11–20 mm | 166(44.5) | 22(34.4) | |

| >20 mm | 145(38.5) | 42(65.6) | 0.0002 |

| Grade | |||

| I | 11(2.9) | 2(3.1) | |

| II | 175(46.9) | 34(53.1) | |

| III | 129(34.6) | 24(37.5) | |

| Lobular | 58(15.6) | 4(6.3) | 0.272 |

| LVI | |||

| Yes | 154(41.3) | 11(17.2) | |

| No | 219 (58.7) | 53(82.8) | 0.001 |

| Multifocality | |||

| Yes | 132 (35.4) | 6(9.4) | |

| No | 241(64.6) | 58(90.6) | 0.0001 |

| ER positive | 290(77.7) | 53(82.8) | |

| ER negative | 83(22.3) | 11(17.2) | 0.362 |

| No. of positive SLN | |||

| 1 only | 265(71) | 51(79.7) | |

| 2 | 75(29) | 9(14.1) | |

| 3 | 21(5.6) | 3(4.7) | |

| 4 | 8(2.1) | 1(1.6) | |

| >5 | 4(1.1) | 0(0) | 0.651 |

| No. of negative SLN | |||

| 0 | 132(35.4) | 10(15.6) | |

| 1 | 79(21.2) | 18(28.1) | |

| 2 | 72(19.3) | 15(23.4) | |

| 3 | 41(11) | 13(20.3) | |

| 4 | 22(5.9) | 4(6.3) | |

| >5 | 27(7.2) | 4(6.3) | 0.03 |

| ≥3 nodes harvested | 24.10 % | 64.10 % | |

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve to calculate the discriminatory accuracy of MSKCC nomogram in predicting NSLN metastasis. AUC = 0.558 (95 % CI = 0.406 to 0.710)

Discussion

Over the past two decades early diagnosis and effective systemic adjuvant therapy has led to improved survival [17, 18] after breast cancer treatment and researchers have now focused on improving the quality of life in long term survivors. More conservative approach has been adopted in breast cancer surgery over this period with breast conservation surgery (BCS) and sentinel node biopsy replacing mastectomy and axillary clearance in eligible patients, offering them a better quality of life.For the majority of patients with pathologically positive SLNs, completion ALND is recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology Guidelines and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. However recent ACSOG Z-011 trial demonstrated that patients with limited sentinel node positivity (1–2 SLNs) treated with breast conservation surgery, adjuvant whole breast irradiation and systemic therapy did not benefit from completion ALND [19].Currently, Z-011 results would have to be applied with great caution to patients undergoing mastectomy since they may not receive adjuvant radiotherapy as was the case in all Z-011 patients. Breast cancer surgeons are now debating about the requirement of axillary clearance in all sentinel positive cases proposing a more selective approach based on individual risk [20–25].

Authors have identified that tumor and nodal characteristics act together to impact the occurrence of NSLN metastasis. An important tumor characteristic that increases the likelihood of NSLN metastasis is tumor size [26–28]. Joseph et al. [27] observed in his study that incidence of NSLN metastasis in T1a, T1b and T1c tumors were 0, 12 and 42 % respectively. Boler et al. [29] in his study reveals that 30 % of T1 tumors and 45 % of T2 tumors had NSLN involvement. Other tumor characteristics reported to be associated with NSLNM are tumor grade [30, 31] and lymphovascular invasion (LVI) [29–32]. In our study, we could not identify a statistically significant association of tumour size, grade and lymphovascular invasion with non-SLN metastasis which could be due to smaller sample size and fewer subjects having NSLN metastasis (n = 20).

Overall size of metastasis in sentinel node is demonstrated to be one of the most significant predictor of residual axillary disease in axilla. In a meta-analysis by Degnim et al. [33], sentinel node metastasis size appeared to be the strongest predictor of non-SLN involvement. Reynold et al. [34] and Chu et al. [35] reported a NSLN involvement rate of 5 % and 6 % respectively, in patients with T1 tumors and SLN micrometastasis. In our study, we identified that patients who had micrometastasis in SLNB (n = 3) had no additional nodal involvement in completion ALND. Several centers are now considering omission of ALND in SLN micrometastasis patients as a safe option, given the low rate of additional metastasis in completion ALND. The results of the NSABP B-32 [36] and ACOSOG Z0010 [37] trials suggest that SLN micrometastases found only by IHC are clinically insignificant.

The number of positive SLNs and nodal ratio (SLN positive/SLN harvested) are demonstrated to be associated with additional nodal metastasis. ACSOG Z-011 trial has specifically limited cases with 1–2 SLNs positive to SLNB alone group on the basis that this group has lesser risk of residual disease in axilla. Wong et al. [26], Boler et al. [29], Chu et al. [35] found in their respective studies that 50, 51 and 56 % of cases with multiple positive sentinel nodes (>1 SLN +) had NSLN involvement as compared to 32, 30 and 31 % of patients with 1 SLN+. In our study, 53.8 % of patients with more than one sentinel node positive had NSLN involvement as compared to 25.3 % in patients with single positive SLN. Multiple SLNs positivity had a significant association (p = 0.04) with NSLN involvement in univariate analysis. Also 41.9 % of individuals with nodal ratio ≥ 0.5 had NSLN involvement as against 21.3 % in nodal ratio < 0.5 (though not statistically significant). In summary our study a positive correlation exists between SLN size, no. of positive SLNs and nodal ratio and NSLN metastasis (although statistically significant association was obtained only in multiple SLN positivity).

Extra-capsular invasion (ECI) in sentinel nodes is proved to be one of the strongest predictor of further metastasis in axilla. ECI of the SLN occurs at vascular root of lymphnode hilum and represents tumor deposits in transit to other sites [38]. Most studies have observed that 60–70 % of patients with ECI in SLNs have NSLN positivity as compared to 20–30 % in ECI negative cases [29, 30, 39–43]. Similarly in our study 73 % of cases with ECI in SLNs had NSLN metastasis. We also observed ECI to be independent predictive factor for NSLN metastasis in both univariate and multivariate analysis.

Based upon the tumor and sentinel nodal characteristics associated with non-SLN metastasis, MSKCC group developed a nomogram to calculate the risk of NSLN metastasis which could guide the physician and patient on decision making of ALND. It takes into consideration 8 variables for risk assessment and is likely to perform better diluting the differences in patient/tumor characteristics and pathological assessment. However validation by external groups has only yielded discordant results (Table 3). The probable reasons quoted for discrepancy are differences in age, tumor/sentinel characteristics, heterogeneity in SLNB technique and pathological assessment.

Table 3.

Validation of MSKCC nomogram in literature

| Authors, country, year | Sample size | AUC |

|---|---|---|

| Coutant et al., France, 2009 [44] | 561 | 0.78 |

| Smidt et al., The Netherlands, 2005 [45] | 222 | 0.77 |

| Lombardi et al. Italy, 2011 [46] | 139 | 0.76 |

| Soni et al., Australia, 2005 [47] | 149 | 0.75 |

| Kuo et al., Taiwan, 2013 [48] | 324 | 0.738 |

| Hidar et al., Tunisia, 2011 [49] | 87 | 0.73 |

| Sasada et al., Japan, 2012 [50] | 116 | 0.73 |

| Alran et al., France, 2007 [12] | 588 | 0.724 |

| Amanti et al., Italy, 2009 [51] | 61 | 0.72 |

| Ponzone et al., Italy, 2007 [13] | 186 | 0.71 |

| Van la Parra et al., The Netherlands, 2009 [52] | 182 | 0.71 |

| Gur et al., Turkey, 2010 [53] | 607 | 0.705 |

| Poirier et al., Canada, 2008 [54] | 209 | 0.687 |

| Piñero et al., Spain, 2012 [55] | 501 | 0.684 |

| Pal et al., United Kingdom, 2008 [5] | 118 | 0.68 |

| Coufal et al., Czech Republic 2009 [56] | 330 | 0.68 |

| Van der Hoven et al., The Netherlands, 2010 [57] | 168 | 0.68 |

| Sanjuán et al., Spain, 2010 [58] | 114 | 0.67 |

| Moghaddam et al., United Kingdom, 2010 [59] | 108 | 0.63 |

| Fougo et al., Portugal, 2011 [60] | 98 | 0.67 |

| Klar et al., Germany, 2008 [15] | 98 | 0.58 |

AUC values less than 0.7 are italicized

A model performs accurately when the population where it is to be applied is similar to the original cohort where the nomogram was devised. Degnim et al. [33] and Meretoja et al. [40] have demonstrated that performance of a nomogram diminishes when transported from one population to other. Ponzone et al. [13] observed that compared to their group, the MSKCC original series had significantly higher proportion of patients with ≥3 SLNs removed (24 % vs. 8 %). This could be due to differences in the SLNB concept across these countries. Surgeons in Italy advocate minimum nodes to be excised in SLNB [61] whereas some American surgeons propose an opposite view [62]. These differences are also likely to be reflected in nomogram results, since higher number of SLNs retrieved could also result in greater number of positive/negative SLNs both of which has strong impact on the nomogram score. Addressing these issues, Klar et al. [15] proposed that standardization of SLNB techniques and pathologic assessment would be desirable but this might be difficult to achieve.

In our validation study the AUC for the entire patient set was 0.58 suggesting poor discriminatory ability. We had greater proportion of patients in T2 category. A subset analysis was done for T1 and T2 tumors separately to ascertain whether the nomogram performed better in T1 tumors. The AUC values were lower than 0.7 (0.55 for T2 and 0.60 for T1) for both groups suggesting poor accuracy.

Besides varied accuracy in different settings, another limitation of nomogram is its poor performance in low risk category. Gábor Cserni [63] elaborated that a test may be accurate in general but can have limited utility in clinically relevant subset. He demonstrated that even in studies which had AUC values >0.7, the observed risk of NSLN metastasis in the low risk group is considerably higher than estimated risk (Table 4). For example in study by Degnim et al. [66] from Mayo clinic, estimated risk of patients with 0–10 % score was 6 % which means that 6 out of 100 patients with a score of 0–10 % by nomogram might have additional nodal metastasis. But in reality 14 % had additional nodal disease. Furthermore it implies that 14 % of patients would have NSLN metastasis if axillary dissection is omitted based on cut-off of 10 % score. In summary, the low probability sub-group indeed has high false negative rates, which could result in under treatment in these patients defeating the very purpose of nomogram. In our study the entire cohort had scores ranging from 20 to 75 % and thus we could not predict the false negative rates with a cut-off of 10 %.

Table 4.

Studies showing underestimation of NSLN metastasis in low-risk category

| Study (number of SLN+) | AUC | Low-risk decile | Estimated risk in low risk decile | Observed risk in low risk decile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kocis L et al. (140) [64] | 0.73 | 0–8 % | 6 % | 14 % |

| Smidt ML et al. [45] | 0.77 | NA | 10 % | 20 % |

| Soni NK et al. [65] | 0.75 | 0–10 % | 10 % | 16 % |

| Degnim AC Mayo (462) [66] | 0.72 | 0–10 % | 10 % | 14 % |

| Degnim AC Michigan (69) [66] | 0.86 | 0–10 % | 10 % | 11 % |

| Cripe MH (92) [11] | 0.82 | 0–13 % | 9 % | 11 % |

SLN micrometastasis is another low risk factor for NSLNM but several reports indicate poor accuracy of MSKCC nomogram in this subgroup. Several groups [12, 67, 68] have demonstrated poor predictability of MSKCC nomogram in SLN micrometastasis. This is probably because MSKCC nomogram does not include size of SLN metastasis in its calculation [12]. Van zee et al. admits that volume of metastasis in SLN would be an accurate marker but its measurement can be time consuming and impractical. The authors have used method of detection as a surrogate for SLN size of metastasis in concurrence with previous reports indicating that method of detection correlated with the nodal burden in sentinel nodes [69, 70].

All the above studies indicate that a select sub-set of patients with favorable tumor characteristics (no adverse pathologic features like ECI, LVI, and multiple SLN positivity) have a low probability of residual disease in axilla. Though MSKCC nomogram proved to be accurate in several centers, it could not reliably predict the involvement of NSLN in our study group. Risk factor identified in our study group (ECI) is not a part of MSKCC nomogram which could be the reason for poor performance in our cohort. Similar to our study, an Italian study group [3] identified ECI and SLN macro metastasis to be significant risk factors for NSLNM. They developed a modified prediction tool incorporating these factors into MSKCC nomogram and found it to be with improved specificity.

The usefulness of nomogram should also be seen in the light of results from the AMAROS [71] and ACSOG- Z11 [19] trials which demonstrated that in select subset of sentinel node positive patients, SLNB alone or axillary radiotherapy provide excellent and comparable axillary control as ALND but with reduced arm morbidity. These studies could be practice changing with regard to the need for axillary surgery in node positive women. Until such time where ALND omission becomes a standard of care, these nomograms might serve as useful adjunct to identify risk of NSLNM and individualize the treatment based on the risk category. More data is required to identify risk factors associated with NSLNM in Indian patients and future studies can also modify the existing tools by incorporating the risk factors identified in our population. Lastly our study is limited by sample size and retrospective validation of nomogram. Prospective validation in consecutive patients is desired to ascertain the accuracy of a nomogram.

Conclusions

In our study, sentinel nodes are the only nodes to be involved by tumor in 70 % of the patients. Our findings indicate that multiple sentinel node positivity and extra-capsular invasion in sentinel node significantly predicted the likelihood of additional nodal metastasis. MSKCC nomogram did not reliably predict the involvement of additional nodal metastasis in our study group. Further studies with large sample size can identify risk factors associated with NSLNM in Indian patients and can validate other prediction tools for NSLN involvement to find the most appropriate one for our population.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Sources of Funding

The authors declare no sources of funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical Approval

For this type of study formal ethical clearance is not required.

References

- 1.Petrek JA, Heelan MC. Incidence of breast carcinoma-related lymphedema. Cancer. 1998;83:2776–2781. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981215)83:12B+<2776::AID-CNCR25>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Galimberti V, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy to avoid axillary dissection in breast cancer with clinically negative lymph-nodes. Lancet. 1997;349:1864–1867. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scomersi S, Torelli L, Zanconati F, et al. Evaluation of a breast cancer nomogram for predicting the likelihood of additional nodal metastases in patients with a positive sentinel node biopsy. Ann Ital Chir. 2012;83:461–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Zee K. J., Manasseh D. M., Bevilacqua J. L., et al. A nomogram for predicting the likelihood of additional nodal metastases in breast cancer patients with a positive sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:1140–1151. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2003.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pal A, Provenzano E, Duffy SW, Pinder SE, Purushotham AD. A model for predicting non-sentinel lymph node metastatic disease when the sentinel lymph node is positive. Br J Surg. 2008;95:302–309. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohrt HE, Olshen RA, Bermas HR, et al. New models and online calculator for predicting non-sentinel lymph node status in sentinel lymph node positive breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barranger E, Coutant C, Flahault A, et al. An axilla scoring system to predict non-sentinel lymph node status in breast cancer patients with sentinel lymph node involvement. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;91:113–119. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-5781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang RF, Krishnamurthy S, Hunt KK, et al. Clinicopathologic factors predicting involvement of nonsentinel axillary nodes in women with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:248–254. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2003.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soni N, Carmalt H, Gillett D, et al. Evaluation of a breast cancer nomogram for prediction of non-sentinel lymph node positivity. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:958–964. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert L, Ayers G, Hwang R, Hunt K, Ross M, Kuerer H, et al. Validation of a breast cancer nomogram for predicting nonsentinel lymph node metastases after a positive sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:310–320. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cripe M, Beran L, Liang W, Sickle-Santanello B. The likelihood of additional nodal disease following a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients: validation of a nomogram. Am J Surg. 2006;192:484–487. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alran S, de Rycke Y, Fourchotte V, et al. Validation and limitations of use of a breast cancer nomogram predicting the likelihood of non-sentinel node involvement after positive sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2195–2201. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ponzone R, Maggiorotto F, Mariani L, et al. Comparison of two models for the prediction of nonsentinel node metastases in breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2007;193:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van la Parra RF, Francissen CM, Peer PG, Ernst MF, et al. Assessment of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center nomogram to predict sentinel lymph node metastases in a Dutch breast cancer population. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(3):564–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klar M, Jochmann A, Foeldi M, et al. The MSKCC nomogram for prediction the likelihood of non-sentinel node involvement in a German breast cancer population. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112(3):523–531. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9884-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hidara S, Harrabia I, Benregaya L, et al. Validation of nomograms to predict the risk of non-sentinel lymph node metastases in North African Tunisian breast cancer patients with sentinel node involvement. Breast. 2011;20:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tryggvadóttir L., Gislum M., Bray F., et al. Trends in the survival of patients diagnosed with breast cancer in the Nordic countries 1964–2003 followed up to the end of 2006. Acta Oncol. 2010;49(5):624–631. doi: 10.3109/02841860903575323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sant M., Allemani C., Santaquilani M., et al. EUROCARE-4. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed in 1995–1999. Results and commentary. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(6):931–991. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuliano A, Linda McCall L, Beitsch P, et al. Locoregional recurrence after sentinel lymph node dissection with or without axillary dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node metastases. The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 Randomized Trial. Ann Surg. 2010;252:426–433. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f08f32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatzemeier W, Mann GB. Which sentinel lymph-node (SLN) positive breast cancer patient needs an axillary lymph-node dissection (ALND)–ACOSOG Z0011 Results and beyond. Breast. 2013;22(3):211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noguchi M. Avoidance of axillary lymph node dissection in selected patients with node-positive breast cancer. EJSO. 2008;34:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langer I, Guller U, Viehl CT, et al. Axillary lymph node dissection for sentinel lymph node micrometastases may be safely omitted in early-stage breast cancer patients: long-term outcomes of a prospective study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(12):3366–3374. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0660-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponzone R, Biglia N, Maggiorotto F, et al. Performance of sentinel node dissection as definitive treatment for node negative breast cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:703–706. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giuliano AE, Morrow M, Duggal S, Julian TB. Should ACOSOG Z0011 change practice with respect to axillary lymph node dissection for a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer? Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;29:687–692. doi: 10.1007/s10585-012-9515-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Angelo-Donovan DD, Dickson-Witmer D, Petrelli NJ. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: a history and current clinical recommendations. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong SL, Edwards MJ, Chao C, et al. Predicting the status of the nonsentinel axillary nodes. Arch Surg. 2001;136:563–568. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joseph KA, El-Tamer M, Komenaka I, Troxel A, et al. Predictors of nonsentinel node metastasis in patients with breast cancer after sentinel node metastasis. Arch Surg. 2004;139:648–651. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.6.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang RF, Krishnamurthy S, Hunt KK, et al. Clinicopathologic factors predicting involvement of nonsentinel axillary nodes in women with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:248–253. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2003.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boler D.E., Uras C., Ince U, et al. Factors predicting the non-sentinel lymph node involvement in breast cancer patients with sentinel lymph node metastases. Breast. 2012;21:518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner RR, Chu Ku, Qi K, Hansen NM, Glass EC, Giuliano AE. Pathologic features associated with nonsentinel lymph node metastases in patients with metastatic breast carcinoma in a sentinel lymph node. Cancer. 2000;89:574–581. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<574::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohrt HE, Olshen RA, Bermas HR, Goodson WH, Wood DJ, et al. New models and online calculator for predicting non-sentinel lymph node status in sentinel lymph node positive breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiser MR, Montgomery LL, Tan LK, et al. (2001) Lymphovascular invasion enhances the prediction of non-sentinel node metastases in breast cancer patients with positive sentinel nodes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:145–149. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0145-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Degnim AC, Griffith KA, Sabel MS, et al. Clinicopathologic features of metastasis in nonsentinel lymph nodes of breast carcinoma patients: a metaanalysis. Cancer. 2003;98:2307–2315. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reynolds C, Mick R, Donohue JH, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy with metastasis: can axillary dissection be avoided in some patients with breast cancer? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1720–1726. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.6.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chu KU, Turner RR, Hansen NM, et al. Do all patients with sentinel node metastasis from breast carcinoma need complete axillary node dissection? Ann Surg. 1999;229:536–541. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199904000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:927–933. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70207-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hunt KK, Ballman KV, McCall LM, Boughey JC, Mittendorf EA, et al. Factors associated with local-regional recurrence after a negative sentinel node dissection: results of the ACOSOG Z0010 trial. Ann Surg. 2012;256:428–436. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182654494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldstein NS, Mani A, Vicini F, Ingold J. Prognostic features in patients with stage T1 breast carcinoma and a 0.5 cm or less lymph node metastasis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111:21–28. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/111.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eldweny H, Alkhaldy K, Alsaleh N, et al. Predictors of non-sentinel lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients with positive sentinel lymph node pilot study. J Egypt Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;24(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meretoja TJ, Leidenius MHK, Heikkilä PS, et al. International multicenter tool to predict the risk of nonsentinel node metastasis in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(24):1888–1896. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stitzenberg KB, Meyer AA, Stern SL, et al. Extracapsular extension of the sentinel lymph node metastasis: a predictor of nonsentinel node tumor burden. Ann Surg. 2003;237:607–612. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000064361.12265.9A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moosavi SA, Abdirad A, Omranipour R, et al. Clinicopathological Factors Predicting Non-Sentinel Lymph Node Metastasis of Breast Cancer in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:7049–7054. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.17.7049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ozmen V, Karanlik H, Cabioglu N, et al. Factors predicting the sentinel and nonsentinel lymph node metastases in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;95:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coutant C, Olivier C, Lambaudie E, Fondrinier E, Marchal F, Guillemin F, et al. Comparison of models to predict nonsentinel lymph node status in breast cancer patients with metastatic sentinel lymph nodes: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2800–2808. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.7418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smidt M.L., Kuster D.M., van der Wilt G.J., et al. Can the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center nomogram predict the likelihood of nonsentinel lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients in The Netherlands? Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:1066–1072. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lombardi A, Maggi S, Lo Russo M, Scopinaro F, Di Stefano D, Pittau MG, et al. Non-sentinel lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients with a positive sentinel lymph node: validation of five nomograms and development of a new predictive model. Tumori. 2011;97:749–755. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soni NK, Carmalt HL, Gillett DJ, Spillane AJ, et al. Evaluation of a breast cancer nomogram for prediction of non-sentinel lymph node positivity. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:958–964. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuo YL, Chen WC, Yao WJ, et al. Validation of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center nomogram for prediction of non-sentinel lymph node metastasis in sentinel lymph node positive breast cancer patients an international comparison. Int J Surg. 2013;11(7):538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hidar S, Harrabi I, Benregaya L, Fatnassi R, Khelifi A, Benabdelkader A, et al. Validation of nomograms to predict the risk of non-sentinels lymph node metastases in North African Tunisian breast cancer patients with sentinel node involvement. Breast. 2011;20:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sasada T, Murakami S, Kataoka T, Ohara M, Ozaki S, Okada M, et al. Memorial SloaneKettering Cancer Center nomogram to predict the risk of non-sentinel lymph node metastasis in japanese breast cancer patients. Surg Today. 2012;42:245–249. doi: 10.1007/s00595-011-0088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amanti C, Lombardi A, Maggi S, Moscaroli A, Lo Russo M, Maglio R, et al. Is complete axillary dissection necessary for all patients with positive findings on sentinel lymph node biopsy? Validation of a breast cancer nomogram for predicting the likelihood of a non-sentinel lymph node. Tumori. 2009;95:153–155. doi: 10.1177/030089160909500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van la Parra RF, Ernst MF, Bevilacqua JL, Mol SJ, Van Zee KJ, Broekman JM, et al. Validation of a nomogram to predict the risk of nonsentinel lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients with a positive sentinel node biopsy: validation of the MSKCC breast nomogram. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1128–1135. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0359-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gur AS, Unal B, Ozbek U, Ozmen V, Aydogan F, Gokgoz S, et al. Validation of breast cancer nomograms for predicting the non-sentinel lymph node metastases after a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in a multi-center study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poirier E, Sideris L, Dube P, Drolet P, Meterissian SH. Analysis of clinical applicability of the breast cancer nomogram for positive sentinel lymph node: the Canadian experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2562–2567. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pinero A, Canteras M, Moreno A, Vicente F, Gimenez J, Tocino A, et al. Multicenter validation of two nomograms to predict non-sentinel node involvement in breast cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0887-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coufal O, Pavlik T, Fabian P, Bori R, Boross G, Sejben I, et al. Predicting nonsentinel lymph node status after positive sentinel biopsy in breast cancer: what model performs the best in a Czech population? Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:733–740. doi: 10.1007/s12253-009-9177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van den Hoven I, Kuijt GP, Voogd AC, et al. Value of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center nomogram in clinical decision making for sentinel lymph node-positive breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1653–1658. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanjuan A, Escaramis G, Vidal-Sicart S, Illa M, Zanon G, Pahisa J, et al. Predicting non-sentinel lymph node status in breast cancer patients with sentinel lymph node involvement: evaluation of two scoring systems. Breast J. 2010;16:134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moghaddam Y, Falzon M, Fulford L, Williams NR, Keshtgar MR. Comparison of three mathematical models for predicting the risk of additional axillary nodal metastases after positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in early breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1646–1652. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fougo JL, Senra FS, Araujo C, Dias T, Afonso M, Leal C, et al. Validating the MSKCC nomogram and a clinical decision rule in the prediction of non-sentinel node metastases in a Portuguese population of breast cancer patients. Breast. 2011;20:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Forza Operativa sul Carcinoma Mammario. Linee guida sulla diagnosi,il trattamento e la riabilitazione. Aggiornamento 2005 (2005) Attualità Senologia 46:33–106

- 62.Woznick A, Franco M, Bendick P, Benitez PR. Sentinel lymph node dissection for breast cancer: how many nodes are enough and which technique is optimal? Am J Surg. 2006;191:330–333. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cserni G. Comparison of different validation studies on the use of the Memorial-Sloan Kettering Cancer Center nomogram predicting nonsentinel node involvement in sentinel node–positive breast cancer patients. Letters to the Editor. Am J Surg. 2007;194:699–700. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kocsis L., Svebis M., Boross G., et al. Use and limitations of a nomogram predicting the likelihood of non-sentinel node involvement after a positive sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer patients. Am Surg. 2004;70:1019–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soni N.K., Carmalt H.L., Gillett D.J., Spillane A.J. Evaluation of a breast cancer nomogram for prediction of non-sentinel lymph node positivity. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:958–964. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Degnim A.C, Reynolds C., Pantvaidya G., et al. Nonsentinel node metastasis in breast cancer patients: assessment of an existing and a new predictive nomogram. Am J Surg. 2005;190:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gur AS, Unal B, Johnson R, Ahrendt G, Bonaventura M, Gordon P, et al. Predictive probability of four different breast cancer nomograms for nonsentinel axillary lymph node metastasis in positive sentinel node biopsy. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.D’Eredità G, Troilo VL, Giardina C, et al. Sentinel lymph node micrometastasis and risk of non-sentinel lymph node metastasis: validation of two breast cancer nomograms. Clin Breast Cancer. 2010;10(6):445–451. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.n.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kamath VJ, Giuliano R, Dauway EL, et al. Characteristics of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer predict further involvement of higher-Echelon nodes in the axilla. Arch Surg. 2001;136:688–692. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.6.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rahusen FD, Torrenga H, van Diest PJ, et al. Predictive factors for metastatic involvement of nonsentinel nodes in patients with breast cancer. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1059–1063. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.9.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981–22023 AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2014;15:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70460-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]