Abstract

Background

The trends observed in cancer breast among Indian women are an indication of effect of changing lifestyle in population. To draw an appropriate inference regarding the trends of a particular type of cancer in a country, it is imperative to glance at the reliable data collected by Population Based Cancer Registries over a period of time.

Objective

To give an insight of changing trends of breast cancer which have taken place over a period of time among women in Cancer Registries of India. Breast Cancer trends for invasive breast cancer in women in Indian Registries have varied during the selected period. Occurrence of breast cancers has also shown geographical variation in India.

Materials and Methods

This data was collected by means of a ‘Standard Core Proforma’ designed by NCRP conforming to the data fields as suggested by International norms. The Proforma was filled by trained Registry workers based on interview/ hospital medical records/ supplementing data by inputs from treating surgeons/radiation oncologists/involved physicians/pathologists. The contents of the Proforma are entered into specifically created software and transmitted electronically to the coordinating center at Bangalore. The registries contributing to more number of years of data are called as older registries, while other recently established registries are called newer registries.

Results

While there has been an increase recorded in breast cancer in most of the registries, some of them have recorded an insignificant increase. Comparison of Age Adjusted Rates (AARs) among Indian Registries has been carried out after which trends observed in populations covered by Indian Registries are depicted. A variation in broad age groups of females and the proneness of females developing breast cancer over the period 1982 to 2010 has been shown. Comparisons of Indian registries with International counterparts have also been carried out.

Conclusions

There are marked changes in incidence rates of cancer breast which have occurred in respective registries in a developing country like India. A steady increase in AARs in most of the registries of India including the newly established registries is indicative of the fact that cancer breast poses a threat to women in India.

Keywords: Population Based Cancer Registries , Cancer Breast, Age Adjusted Rates, Time Trends, Geographic variation

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death in women worldwide [1]. The purpose of this publication is to highlight the changing trends of breast cancer which have taken place over a period of time among females in Indian Cancer registries. It mainly contains extracts of the published report on “Time Trends in Cancer Incidence Rates” by National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research (NCDIR) –National Cancer Registry Programme (NCRP). For the sake of discussion of descriptive epidemiology of breast cancer, the data of the years 1982–2010 collected by Population Based Cancer Registries (PBCRs) has been considered. Breast Cancer trends for invasive breast cancer in females in Indian Registries have varied during the selected period. Occurrence of breast cancers has also shown geographical variation in India.

A National Cancer Registry Programme (NCRP) was developed in 1982; under the auspices of Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). At present, there are 29 Population Based Cancer Registries and 9 Hospital Based Cancer Registries actively involved in data collection which is covering part of population of India. The population of India in general and that of areas covered by the registries in particular have displayed rapid changes in lifestyles, dietary practices and socioeconomic status. Diagnostic and detection technologies have improved and more population has not only access, but also can afford the same.

The registries which have been operational since 1982 or 1988 are termed as “older PBCRs” for discussion. Since they are functioning for a longer period of time, the time trend based on 5 years Average Age Adjusted Rates (AARs) for at least five such periods can be examined. This provides potency to the findings. The second category of seven registries have contributed at least 7 years of data. All other registries listed have contributed to 5–6 years of data.

Data and Methods

The published data from ‘Time Trends in Cancer Incidence Rates’ published by NCRP (NCDIR) in July 2013 [2] has been used. The data pertains to newly diagnosed cases (incidence) of Cancer Breast among Indian females reported from (a) Six (06) Population Based Cancer Registries that have been involved in providing data for more than two decades (Series A) (b) Seven (07) Population Based Cancer Registries (Series B) that have been involved in providing data for at least 7 years to Coordinating Centre at Bangalore.(c) Six (06) other PBCRs (Series C) consisting of data of 5–6 years. This data was collected by means of a ‘Standard Core Proforma [3]’ designed by NCRP conforming to the data fields as suggested by International norms [4]. The Proforma was filled by trained Registry workers based on interview/ hospital medical records/ supplementing data by inputs from treating surgeons/radiation oncologists/involved physicians/pathologists. The contents of the Proforma were entered into specifically created software and transmitted electronically to the coordinating center at Bangalore. At the center, the data was subjected to range and consistency checks [5]. This data is published periodically as Consolidated Reports by NCRP (NCDIR). Probable duplicates are removed after due consultation with registries.

The information on confirmed malignant cases of Cancer Breast (ICD 10: C50) [6] for women is presented in this article. This includes retrospective data collected from 84,513 cases under Series A and 4495 cases under Series B above, a total of 89,008 cases. The data from Series C who have data collection of 5–6 years has not been analysed. For comparability, the Age Adjusted Rates (AARs) have been used (rates observed in the study have been adjusted to World Standard Population). The inclusion criteria for the PBCR were that the patient should be residing in the demarcated geographic registry area for at least 1 year. Also, only confirmed malignancy cases were included (behaviour code ≥3). Exclusion criteria for the PBCR were cases outside the geographical boundaries of the registry, cases with suspected/ benign tumour of the breast.

At present, the Population Based Cancer Registries actively involved in data collection cover part of the population (approximately 7.45 %) [7]. The Registries have been set up in prominent Oncology Centres / Hospitals (Govt. & private) of respective urban/ rural population. For the purpose of statistical analysis, the population census data [8] of India pertaining to the corresponding decade has been referred to. In determining the significance of trends, the actual value of Age Adjusted Standardised Rates (AAR) for a single year, 3 years moving average and 5 years range has been used. This significance of time trend in each PBCR was assessed based on the methods and formula provided by Boyle and Parkin, 1991. In addition, for single year the Joinpoint Regression Program [9] of NCI of USA has been used (Kim et al., 2001). As mentioned, the numerator data used for the above analysis has undergone a series of Range and Consistency checks each year. Clarifications were sought whenever required from the respective PBCRs and the data finalised thereafter. Joinpoint Regression Program (3.5.2)[*] and SPSS 21.0 were used to analyze the data. The tests of significance have been applied and p values calculated. For the current study, the p value of 0.05 has been set as significant. The statistical significance was arrived at using slope (b) and p-value based on simple linear regression.

The validity and reliability of data thus obtained is evident by the quality of data contributed by each registry. However, Pathology Laboratories with amenities for microscopic diagnosis of cancer and radiation oncology treatment facilities have multiplied, increasing the sources of data collection for registry workers underscoring the greater need for cooperation from more persons and institutions. Software application programmes have considerably enhanced the quality of data.

Results

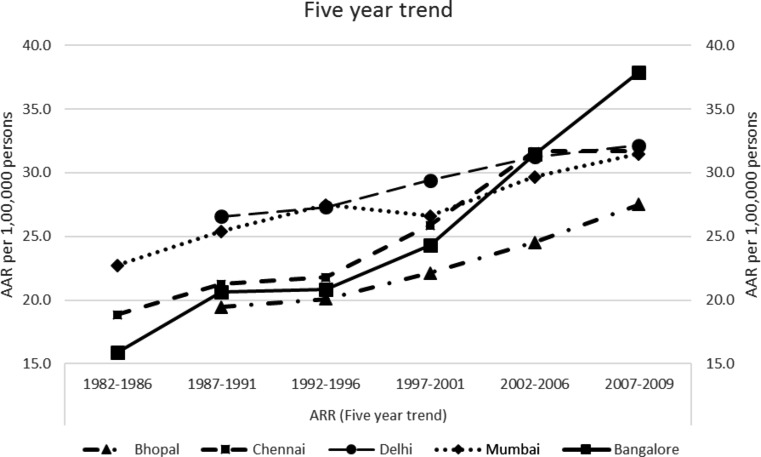

The year-wise incidence rates (AARs) of the older registries (Series A) for Cancer Breast (ICD 10:C50) [6] for the respective years for which data was contributed were observed. The annual trend for registries i.e. Bangalore PBCR showed an increase in AAR by 0.808 (p < 0.001) which points towards higher AARs (on an average) in Bangalore when compared to other older registries (Series A) and same result was indicated in 3 and 5 years AARs for other older registries. With the exception of rural registry of Barshi, all the other older registries have shown a statistically significant rising trend when annual, 3 and 5 years trends (Table 1). The 5 years trend of AARs for older registries has been depicted in form of graph in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Breast cancer (ICD-10: C50) trends over time in AARs by annual, 3 and 5 years among older registries with statistical significance using slope (b) and p value based on simple linear regression (Series A)

| Name of the registries | Years of data | Annual trend | 3 years trend | 5 years trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope (b) | p | Slope (b) | p | Slope (b) | p | ||

| Bangalore | 1982–2009 | 0.808 | <0.0001 | 0.785 | <0.0001 | 0.851 | <0.0001 |

| Chennai | 1982–2009 | 0.587 | <0.0001 | 0.589 | <0.0001 | 0.587 | <0.0001 |

| Mumbai | 1982–2010 | 0.335 | <0.0001 | 0.332 | <0.0001 | 0.322 | <0.0001 |

| Barshi | 1988–2010 | 0.121 | 0.086 | 0.139 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.284 |

| Bhopal | 1988–2010 | 0.394 | <0.0001 | 0.398 | <0.0001 | 0.423 | 0.006 |

| Delhi | 1988–2009 | 0.321 | <0.0001 | 0.318 | <0.0001 | 0.323 | 0.001 |

Fig. 1.

Increasing five year trends over time in AARs among older PBCRs for Breast cancer (ICD-10: C50)

Since the data collection by the newer registries (series B) is for lesser duration, the 3 year moving average over time in AARs has been calculated. Table 2 presents incidence trends by newer registries for a more recent time period. During 2003–2011, the 3 year moving average incidence rate of Thiruvananthapuram was higher when compared to other newer registries and AAR was stable in first three time intervals (AAR of moving average) after which an increase by 2.0 (of AAR) was observed in 2008–2010 with further increase by 2.5 in 2009–2011. This was found to be statistically significant (p = 0.049). Similarly, Ahmedabad Rural also showed a statistically significant (p = 0.028) increase.

Table 2.

Breast cancer (ICD-10: C50) 3 years moving average over time in AARs among newer registries (Series B)

| Name of the registries | AAR (3 years moving average) | Slope(b) | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2005 | 2004–2006 | 2005–2007 | 2006–2008 | 2007–2009 | 2008–2010 | 2009–2011 | |||

| Dibrugarh | 11.0 | 11.5 | 11.8 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 10.8 | 10.6 | −0.068 | 0.638 |

| Kamrup | 20.7 | 17.9 | 15.6 | 16.4 | 19.7 | 23.0 | 22.8 | 0.742 | 0.220 |

| Imphal West | 13.6 | 15.0 | 13.5 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 13.8 | NA | −0.163 | 0.469 |

| Aizawl | 23.4 | 21.3 | 23.1 | 23.1 | 24.6 | 26.0 | 0.654 | 0.072 | |

| Mizoram | 15.6 | 15.1 | 15.4 | 15.0 | 15.2 | 14.9 | −0.092 | 0.130 | |

| Sikkim | 10.2 | 8.1 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 7.8 | 8.2 | −0.102 | 0.706 | |

| Ahm Rural | 9.2 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 10.9 | 11.0 | 0.414 | 0.028 | ||

| Th’puram | 32.6 | 32.6 | 32.6 | 34.6 | 35.1 | 0.687 | 0.049 | ||

Aizawl district and Mizoram state (Series B) have been considered separately to bring out the marked differences in recorded AARs of the urban areas of Aizawl and Mizoram state as a whole.

However, some measure of prudence may be required in drawing conclusions for the newer registries (series B) about the significance of trends as more years of data would provide more stable rates.

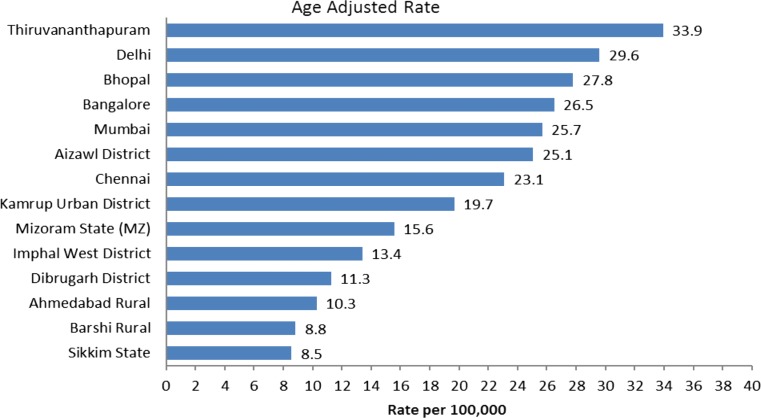

Comparison of Age Adjusted Rates (AARs) Among Indian Registries

On combining the AARs for the respective registries for all calendar years for which they have contributed data, the AARs of listed registries can be represented as a single figure. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Comparison of Age Adjusted Incidence Rates (AARs) - Females –Breast (ICD-10: C50) for all registries (combined AARs for the calendar years for the respective registry)

| Centre name | Age Adjusted Rate |

|---|---|

| Bangalore | 26.5 |

| Barshi Rural | 8.8 |

| Bhopal | 27.8 |

| Chennai | 23.1 |

| Delhi | 29.6 |

| Mumbai | 25.7 |

| Dibrugarh District | 11.3 |

| Kamrup Urban District | 19.7 |

| Imphal West District | 13.4 |

| Mizoram State (MZ) | 15.6 |

| Aizawl District | 25.1 |

| Sikkim State | 8.5 |

| Ahmedabad Rural | 10.3 |

| Thiruvananthapuram | 33.9 |

On comparison of AARs for the listed registries, it was observed that the AARs in all older PBCRs were Bangalore (26.5), Bhopal (27.8) Chennai (23.1), Delhi (29.6) and Mumbai (25.7) while the rural registry at Barshi had AAR as 8.8.

In the newer PBCRs the rates were Thiruvananthapuram (33.9),Aizawl (25.1), Kamrup Urban (19.7), Imphal west (13.4) while Sikkim state (8.8) and Ahmedabad Rural (10.3) showed lower AARs (Table 3). The rural registry of Ahmedabad which has shown statistically significant increase in AAR over time (refer Table 2 above) –has a comparably lower AAR overall.

On graphical presentation, it was seen that among all registries (older and newer), T hiruvananthapuram and Delhi PBCRs had higher rates (Fig. 2). The recently established PBCR at Patiala [10] which has completed the data collection of 2011–12 shows the AARs as 32.5 which is comparable to Thiruvananthapuram. The registries in the North Eastern states have shown marginally lower AARs (except Aizawl district) when compared to other registries.

Fig 2.

Comparison of Age Adjusted Incidence Rates (AARs) –Cancer Breast (ICD-10: C50) for all registries

Trends Observed in Populations Covered by Indian PBCRs

An observation of AARs across the registries and over the years shows a statistically significant increase in AARs over time in all older PBCRs (Series A) of Bangalore with Annual Percentage Change (APC) of 3.3 %, Bhopal (1.7 %) Chennai (2.4 %), Delhi (1.1 %) and Mumbai (1.3 %). For Bangalore PBCR, the APC was 2.4 % in the period 1982–1999 (Table 4) whereas it was 5.3 % during the period 2000–2009 [2].

Table 4.

Breast cancer (ICD-10: C50) trends over time based on value of joinpoint AARs with Annual Percent Change (APC)

| Name of the registries | Joinpoint AARs with Annual Percent Change (APC) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| APC0 | APC1 | APC2 | |

| Bangalore | 3.32* | 2.42* | 5.30* |

| Barshi | 1.36 | – | – |

| Bhopal | 1.74* | – | – |

| Chennai | 2.39* | – | – |

| Delhi | 1.11* | – | – |

| Mumbai | 1.28* | – | – |

*- represents significant APC (p < 0.05) values

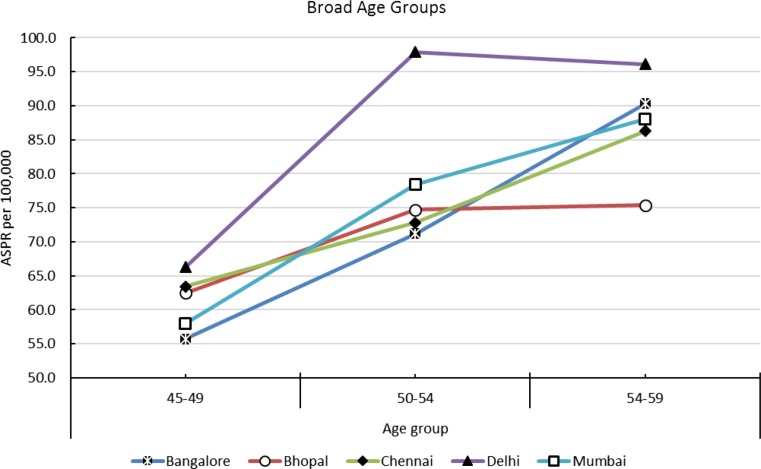

Variation with Broad Age Groups

Table 5 and Fig. 3 indicate the Age specific incidence rates (ASpR) for three broad age groups (45 to 49, 50 to 54 and 55 to 59) for five older registries. Variation in trends in AARs over time, by broad age groups for Cancer Breast in females are particularly important for drawing a comparison between the pre-menopausal and post-menopausal age groups. In Bangalore, Chennai and Mumbai PBCRs there was a significant increase in AARs over time across the age groups starting in the 35–44 age group and in Delhi starting in the 45–54 age group [2]. Additionally in Mumbai PBCR, the age group 0–24 also showed increase in AARs over time [2].

Table 5.

Comparison of Age Specific Rates for Broad Age Groups for Cancer Breast (ICD 10: C50) among older registries

| Name of the registries | Age group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 45–49 | 50–54 | 54–59 | |

| Bangalore | 55.7 | 71.2 | 90.3 |

| Bhopal | 62.5 | 74.7 | 75.4 |

| Chennai | 63.4 | 72.8 | 86.3 |

| Delhi | 66.3 | 97.9 | 96.1 |

| Mumbai | 58.0 | 78.4 | 88.0 |

Fig. 3.

Graphical presentation of Broad Age Groups for Cancer Breast (ICD -10:C50) among older registries

Possibility of One in Number of Women Developing Breast Cancer Over the Period 1982 to 2009 –Lifetime Risk and the Changes Therein!

On comparison of possibility of one in number of women developing breast cancer over the period 1982 to 2009 (Table 6), It is seen that it varied from 1 in 69 in 1982 to 1 in 40 in 2009 for age group 0–64 years. While for the age group 0–74 years, it varied from 1 in 50 in the year 1982 to 1 in 28 in the year 2009 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Possibility of one in number of women developing Breast cancer (ICD-10): C50 for older registries (calculation based on age specific rates from 0–64 and 0–74 years of age)

| Year | 0–64 | 0–74 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangalore | Chennai | Mumbai | Bhopal | Delhi | TVM | Pooled | Bangalore | Chennai | Mumbai | Bhopal | Delhi | TVM | Pooled | |

| 1982 | 78 | 70 | 65 | 69 | 58 | 51 | 47 | 50 | ||||||

| 1983 | 77 | 68 | 63 | 67 | 59 | 50 | 45 | 49 | ||||||

| 1984 | 71 | 67 | 58 | 63 | 53 | 51 | 43 | 47 | ||||||

| 1985 | 77 | 63 | 53 | 59 | 55 | 48 | 37 | 42 | ||||||

| 1986 | 84 | 64 | 56 | 63 | 64 | 46 | 35 | 42 | ||||||

| 1987 | 69 | 64 | 63 | 65 | 49 | 47 | 40 | 44 | ||||||

| 1988 | 68 | 57 | 61 | 67 | 49 | 58 | 48 | 42 | 41 | 51 | 39 | 42 | ||

| 1989 | 62 | 56 | 60 | 66 | 45 | 55 | 45 | 43 | 40 | 46 | 35 | 40 | ||

| 1990 | 61 | 62 | 49 | 61 | 45 | 51 | 47 | 46 | 32 | 47 | 34 | 37 | ||

| 1991 | 52 | 63 | 46 | 66 | 43 | 49 | 38 | 44 | 30 | 51 | 33 | 35 | ||

| 1992 | 64 | 66 | 48 | 65 | 45 | 52 | 42 | 45 | 31 | 45 | 36 | 36 | ||

| 1993 | 59 | 58 | 50 | 64 | 44 | 51 | 40 | 43 | 32 | 45 | 35 | 36 | ||

| 1994 | 68 | 56 | 51 | 54 | 46 | 52 | 45 | 43 | 32 | 44 | 35 | 36 | ||

| 1995 | 60 | 61 | 49 | 60 | 44 | 51 | 40 | 42 | 34 | 53 | 32 | 36 | ||

| 1996 | 61 | 58 | 50 | 65 | 46 | 52 | 44 | 37 | 33 | 51 | 36 | 36 | ||

| 1997 | 61 | 50 | 52 | 55 | 44 | 50 | 45 | 34 | 34 | 44 | 32 | 35 | ||

| 1998 | 53 | 56 | 53 | 56 | 42 | 49 | 39 | 37 | 35 | 41 | 31 | 34 | ||

| 1999 | 55 | 53 | 52 | 52 | 43 | 50 | 41 | 37 | 32 | 43 | 30 | 34 | ||

| 2000 | 52 | 49 | 53 | 56 | 43 | 49 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 40 | 31 | 34 | ||

| 2001 | 49 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 41 | 46 | 31 | 32 | 34 | 41 | 30 | 32 | ||

| 2002 | 47 | 43 | 48 | 53 | 45 | 46 | 32 | 31 | 32 | 39 | 32 | 32 | ||

| 2003 | 46 | 42 | 49 | 59 | 43 | 46 | 32 | 30 | 33 | 43 | 31 | 32 | ||

| 2004 | 42 | 40 | 45 | 48 | 42 | 43 | 30 | 28 | 30 | 36 | 29 | 30 | ||

| 2005 | 38 | 37 | 46 | 43 | 39 | 35 | 41 | 25 | 28 | 30 | 33 | 28 | 28 | 29 |

| 2006 | 36 | 39 | 41 | 51 | 39 | 38 | 40 | 26 | 29 | 27 | 36 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| 2007 | 32 | 40 | 43 | 56 | 39 | 38 | 39 | 22 | 29 | 28 | 41 | 28 | 29 | 28 |

| 2008 | 36 | 42 | 41 | 48 | 41 | 35 | 40 | 24 | 29 | 27 | 34 | 28 | 26 | 28 |

| 2009 | 36 | 39 | 44 | 49 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 24 | 28 | 29 | 33 | 28 | 29 | 28 |

International Comparisons

High-quality population-based cancer incidence data have been collected throughout the world since the early 1960s and published periodically in Cancer Incidence in Five Continents [11] (CI5). Cancer Incidence in five continents (Volume X) has recently been published which depicts recorded data from various continents (68 countries for the year 2003–07). It has been observed that incidence rates vary internationally by more than 5-fold across the globe [1].

Cancer Incidence in five continents (Volume X) mentions higher recorded incidence rates for breast cancer in

New Zealand: Maori (107.4) in Oceania.

Belgium (110.8), France: Somme (105.2), Italy Mantua South (102.1) in Europe.

USA, California, San Francisco Bay Area: Non–Hispanic White (104.1) and USA, California, Los Angeles County: Non–Hispanic White (103.4), USA, Alaska: American Indian (105.3) in North America.

Argentina, Cordoba (78.1) and Argentina, Bahroba Bianca (74.7) in South America.

Zimbabwe, Harare: African (33.9) and Egypt, Gharbiah (45.4) in Africa.

In Asia, comparitively lower rates are found –the higher rates in Asia were in Bahrain: Bahraini (56.0), Japan: Miyagi Prefecture (54.0), Israel: Non–Jews (56.1), Israel: Jews (89.4), Japan: Hiroshima (58.1), Singapore: Chinese (59.2).

Indian registries showing higher rates [7] –Thiruvananthapuram (33.9), new registry at Patiala (32.5) and Delhi (29.6) have lower rates when compared to registries in other continents as well as Asian registries. (Table 7)

Table 7.

Comparison of selected Internationala and Indian Population Based Cancer Registries

| International comparisons | Age Adjusted Rate |

|---|---|

| Delhi | 29.6 |

| Patiala | 32.5 |

| Thiruvananthapuram | 33.9 |

| Japan: Miyagi Prefecture | 54.0 |

| Bahrain: Bahraini | 56.0 |

| Israel: Non–Jews | 56.1 |

| Hiroshima | 58.1 |

| Singapore: Chinese | 59.2 |

| Bahrain: Bahraini | 89.4 |

| Israel: Jews | 89.4 |

| Italy Manua South | 102.1 |

| USA, California, Los Angeles County: Non–Hispanic White | 103.4 |

| USA, California, San Francisco Bay Area: Non–Hispanic White | 104.1 |

| France: Somme | 105.2 |

| USA, Alaska: American Indian | 105.3 |

| New Zealand: Maori | 107.4 |

| New Zealand: Belgium | 110.8 |

aCancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol. X (electronic version). Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available from: http://ci5.iarc.fr, accessed [24 July 2015]

Discussion

The frequency of the most common cancer diagnoses and deaths also varies by geographic areas [1]. An atlas of cancer in India has confirmed suspected features of geography of cancer in India [12]. Such variations have been observed for cancer breast in Indian registries, with the rural registries showing comparably lower rates. The rural registries of Ahmedabad and Barshi have lower rates. The registries in the North Eastern states have shown marginally lower AARs (except Aizawl district) when compared to other registries.

On comparing the AARs of cancer breast with other leading site of cancer among females in India i.e. cancer cervix, it has been observed that the Age Adjusted Rates (AARs) of cancer breast have overtaken those of cancer cervix in most of the PBCRs [7] (Page 55, Chapter 7, Three year Report of the PBCRs: 2009–11). The estimated newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer account for 16.7 % while cervical cancers accounts for 16.1 % among all anatomical sites for India [2, 7] for females. This is indicative of the fact that the incident (newly diagnosed) cases for cancer breast have overtaken cancer cervix as leading site of cancer in most of the Population Based Registries [7].

The primary factors that contribute to the striking international variation in incidence rates include differences in reproductive and hormonal factors [1]. In Indian registries, a significant increasing trend is seen in AARs over time across the age groups starting in the 35–44 age group in older registries which have contributed more years of data. Additionally in Mumbai PBCR, the age group 0–24 also showed increase in AARs over time. These are registries in urban agglomerations where known reproductive factors that increase risk of breast cancer come into play besides age. Though screening for breast cancer with mammography may have prohibitive cost for a developing country like ours, an awareness campaign targeting women of age groups which has shown increase in rates (i.e. commercial products used by that age group) may be of value. Detection of early signs and symptoms by self-examination appears to be the most cost effective, convenient and even medically feasible method of handling the situation.

The proneness to breast cancer has also shown an increase in Indian registries as is evident by increase in possibility of one in number of females developing breast cancer over the selected period. The steady rise in proneness over years is a matter of concern.

A proactive approach towards providing prompt cancer care facilities to these existing cancer breast cases may delay/stall the morbidities occurring due to Cancer Breast. Though the surgical, chemotherapeutic and radiation oncology treatment facilities have multiplied, the health systems may still be ill equipped to deal with this looming threat. The complexities in treating cancer also add to the woes.

Conclusion

A steady increase in AARs in most of the registries of India including the newly established registries is indicative of the fact that cancer breast poses a threat to women in India. Variations have been observed for cancer breast in Indian registries, with the rural registries showing lower rates when compared with their urban counterparts. Despite the increase in various factors within Indian scenario, which can be thought of working as catalysts for development of cancer breast, the rates in Indian registries remain lower than the overall rates observed internationally.

References

- 1.Center M, Siegel R, Jemal A (2011) Global cancer facts & figures. 2nd edn. American Cancer Society

- 2.Nandakumar, et al. Time trends in cancer incidence rates 1982–2010. Bangalore: National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research-National cancer registry Programme (ICMR); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nandakumar, et al (1982) National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research-National cancer registry Programme (ICMR), Proforma accesible at http://www.pbcrindia.org/PBCR_Centre_Login.aspx

- 4.MacLennan R (1991) Chapter 6-“Items of patient information which may be collected by registries” ScientificPub.No.195, Lyon, International Agency for Research on Cancer

- 5.Parkin DM, Chen VW, Ferlay J, Galceran J, Storm HH, Whelan SL. Comparability and quality control in cancer registration (IARC technical reports no. 19) Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems-10th revision 1994, World Health Organisation, Geneva

- 7.Nandakumar, et al. Three year population report of population based cancer registries 2009–11. Bangalore: National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research-National Cancer Registry Programme (ICMR); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Census of India, Registrar Genaral of India, Socio Cultural Tables, C14 Series - Socio Cultural Tables; Population by 5 years age group, by residence and sex, New Delhi 1981, 1991 & 2001(www.censusindia.net).

- 9.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19:335–351. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::AID-SIM336>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Two year report of Population Based Cancer Registry 2011–12: Department of Pathology, Government Medical College, Patiala

- 11.Nandakumar A, Gupta PC, Gangadharan P, Visweswara RN, Parkin DM. Geographic pathology revisited: development of an atlas of cancer in India. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:740–754. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forman D, Bray F, Brewster DH, Gombe Mbalawa C, Kohler B, et al. (2015) Cancer incidence in five continents, Vol. X, IARC Scientific Publication No. 164 [DOI] [PubMed]