Abstract

Aspergillus fumigatus is a conditional pathogen and the major cause of life-threatening invasive aspergillosis (IA) in immunocompromised patients. The early and rapid detection of A. fumigatus infection is still a major challenge. In this study, the new member of the fungal annexin family, annexin C4, was chosen as the target to design a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay for the rapid, specific, and sensitive detection of A. fumigatus. The evaluation of the specificity of the LAMP assay that was developed showed that no false-positive results were observed for the 22 non-A. fumigatus strains, including 5 species of the Aspergillus genus. Its detection limit was approximately 10 copies per reaction in reference plasmids, with higher sensitivity than that of real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) at 102 copies for the same target. Clinical samples from a total of 69 patients with probable IA (n = 14) and possible IA (n = 55) were subjected to the LAMP assay, and positive results were found for the 14 patients with probable IA (100%) and 34 patients with possible IA (61.82%). When detection using the LAMP assay was compared with that using qPCR in the 69 clinical samples, the LAMP assay demonstrated a sensitivity of 89.19% and the concordance rate for the two methods was 72.46%. Accordingly, we report that a valuable LAMP assay for the rapid, specific, and simple detection of A. fumigatus in clinical testing has been developed.

INTRODUCTION

Aspergillus fumigatus, a ubiquitous saprophytic fungus in most parts of the world, is a conditional pathogenic fungus and the major cause of invasive aspergillosis (IA). The infection is initiated by inhalation of conidia, which are cleared quickly in a normal host but can cause invasive disease in immunocompromised individuals (1). Despite many efforts during the last decade, the morbidity and mortality due to IA has been increasing (2). The poor therapeutic outcomes are associated with the weak host immune status and, importantly, the delayed detection and identification of the causative agent (3).

The traditional culturing method, which is the gold standard for the diagnosis of A. fumigatus, requires several days for observation of growth, is time-consuming, and has only moderate specificity. Laboratory methods for the diagnosis of A. fumigatus include mainly direct microscopic examination, histopathological studies, and serum galactomannan (GM) and (1→3)-β-d-glucan assays. The measurement of galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid shows promise for enhancing the diagnosis of A. fumigatus (4–7), but only approximately 50% of BAL fluid measurement results can match the results of culture and direct examination (8).

PCR-based molecular detection systems for fast and sensitive identification by examination of small amounts of DNA in serum and blood have been developed (9–11). However, the lack of standardization for critical activities in the methods and the evaluation of clinical samples has hampered the development of PCR-based diagnostic tests for clinical use. Real-time quantitative PCR techniques have been used for the detection of a few fungal species, including Scedosporium (12) and Fusarium species in biopsy samples (13). Although the sensitivities and specificities of PCR-based methods are higher than those for conventional methods, there are still some shortcomings, such as the requirements for special equipment and experienced technicians, and the time-consuming nature of the procedures. Therefore, a simple, convenient, and sensitive method for the early detection of A. fumigatus is needed for clinical use.

The loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) technique, developed in 2000 by Notomi and coworkers (14), utilizes Bst DNA polymerase for rapid amplification of specific DNA sequences under isothermal conditions (60 to 65°C), allowing strand displacement DNA synthesis with 4 to 6 specific oligonucleotides that recognize independent regions of the target gene (15). The use of 6 oligonucleotides promotes the speed of the amplification and the specificity, and the output can be up to 109 copies of target DNA molecules within 1 h. The products of LAMP can be visualized in different ways, such as turbidity caused by the precipitation of magnesium pyrophosphate, gel electrophoresis, and the addition of complex ometric dyes, such as SYBR green to observe fluorescence under UV light. Recent reports showed that LAMP had been widely used in the detection of viruses and bacteria (16–18), but it has only recently been applied to some species in the filamentous fungi and yeast genera, including Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus parasiticus, Aspergillus nomius, and Histoplasma capsulatum but not A. fumigatus as yet (19, 20).

In the present study, we developed a rapid and sensitive LAMP assay to detect A. fumigatus using anxC4, a new member of the annexin family, as the target sequence (21). Annexins are widely distributed among eukaryotes and bind phospholipids in a calcium-dependent manner. Annexins are typically composed of a conserved core domain and a variable N-tail domain (22). Annexins are currently classified into five families (A to E), and the fungal annexins belong to the C family (23). The absence of annexins from the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans, and Schizosaccharomyces pombe and their presence in a range of filamentous fungi may suggest a role in providing needed structural support in these organisms (24). Among the fungal annexins, the third member, anxC4, which has an unusually long N-terminal tail and lacks conserved repeats, is significantly different from human annexins, which makes it an attractive target for clinical fungal detection. Hence, this LAMP assay has great potential to be used as a new and simple method for early diagnosis of A. fumigatus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

The study was approved by and carried out under the guidelines of the Ethical Committee of the 307th Hospital of the Academy of Military Medical Sciences (AMMS). All patients provided written informed consent for the collection of samples and subsequent analysis.

Classification of IA.

Research-oriented diagnostic definitions of invasive fungal infection (IFI) were created in 2002 and modified in 2008 by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG). The diagnosis of IA within this classification is made within defined criteria for proven, probable, or possible infection (25), depending on a combination of host factors, clinical manifestations, and mycological factors (26). Briefly, proven IA is defined as microbiological proof of A. fumigatus infection and histopathological evidence of invasive mold infection, probable IA is defined as microbiological proof of A. fumigatus infection after radiological detection, documented by positive cultures for A. fumigatus or galactomannan antigen detection, and possible IA is defined as a new and unexplained well-defined intrapulmonary nodule (with or without a halo sign), an air crescent sign, or a cavity within an area of consolidation that is radiologically documented in an immunocompromised host (27). The purpose of these criteria was to create homogeneous groups for clinical tests, but they have limited ability for detection of early infection (25).

Fungal strains and clinical samples.

A total of 23 strains (1 A. fumigatus and 22 non-A. fumigatus) were used for specificity testing in this study; the 22 non-A. fumigatus strains included 5 other Aspergillus species (Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus terreus, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus versicolor, and Aspergillus nidulans) as detailed in Table 1. A. fumigatus ATCC 13073 was from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC). The other microorganisms or their genomic DNAs were gifts from colleagues from the Academy of Military Medical Sciences and other institutions. In this experiment, the amount of DNA of the A. fumigatus used for specificity evaluation was 0.5 × 105 copies/μl, which is high enough to avoid false-negative amplification results. Strain ATCC 13073 was used for assay optimization, sensitivity evaluation, and verification of the clinical samples. A total of 69 specimens (1 specimen/patient), including 10 bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and 59 blood specimens, were obtained from 69 patients (14 patients with probable IA and 55 patients with possible IA) admitted to the 307th Hospital of the AMMS during the period from October to November 2014. It is worth noting that patients with probable and possible IA received antifungal drug treatment before sampling.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Latin name | Strain |

|---|---|

| Aspergillus fumigatus | ATCC 13073 |

| Aspergillus niger | 3.3928 |

| Aspergillus terreus | Isolated strain |

| Aspergillus flavus | 3.3950 |

| Aspergillus versicolor | Isolated strain |

| Aspergillus nidulans | Isolated strain |

| Candida albicans | ATCC 90028 |

| Candida tropicalis | Isolated strain |

| Candida parapsilosis | ATCC 22019 |

| Candida krusei | ATCC 14243 |

| Candida glabrata | ATCC 90030 |

| Cryptococcus albidus | Isolated strain |

| Cryptococcus uniguttulatus | Isolated strain |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | ATCC 90012 |

| Penicillium citrinum | Isolated strain |

| Penicillium marneffei | Isolated strain |

| Exophiala spinifera | Isolated strain |

| Exophiala dermatitidis | Isolated strain |

| Trichophyton rubrum | Isolated strain |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Isolated strain |

| Histoplasma capsulatum | Isolated strain |

| Staphylococcus aureus Rosenbach | Isolated strain |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Isolated strain |

DNA extraction.

Genomic DNA was extracted with an Omega high-performance (HP) fungal DNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA), which relies on the well-established properties of the cationic detergent cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB), following the manufacturer's instructions with several modifications. Briefly, a portion of the fungal hyphae was ground in liquid nitrogen, transferred into 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes containing 600 μl of CTAB extraction buffer, and homogenized using a vortex mixer at a slow speed for 30 s and then at a high speed for 30 s. The homogenates were capped and incubated at 65°C for 30 min with frequent vortex mixing (Benchmark Scientific Inc., USA) and then cooled on ice for 10 min. Next, 400 μl of a mixture of Tris-saturated phenol (pH of ≥7.8)-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) was added to each homogenate, mixed thoroughly, and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min. The clear supernatants (about 700 μl each) were transferred to clean 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes, and an equal volume of ice-cold isopropanol was added to each tube for precipitation of nucleic acid. The suspensions were reverse mixed, allowed to stand for 5 min, and then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min. The whole DNA extraction process was performed according to the Omega protocol for fungal DNA extraction (28). The supernatant was decanted, and 40 μl of sterile, deionized water was added to the pellet to dissolve the nucleic acid.

LAMP primers and reaction conditions.

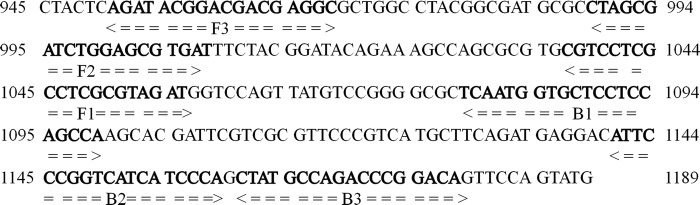

Primer design is the most critical step in development of a successful LAMP assay. Based on the specific and conserved sequences of the anxC4 gene, a set of 3 primers targeted to the anxC4 gene of the species A. fumigatus was designed by using Primer Explorer V4 software (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; http://primerexplorer.jp/elamp4.0.0/index.html). After comparative experiments, we chose one pair of primers. The primers shown in Table 2 were synthesized by Genomics Institution (Beijing, China). The primer sequences and their positions in the expression site of the anxC4 gene are shown in Fig. 1. All LAMP reactions were performed with the Loopamp amplification kit (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd.) in a 25-μl mixture containing 40 pmol (each) of the FIP and BIP primers, 5 pmol (each) of the F3 and B3 primers, 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 20 mM KCl, 16 mM MgSO4, 20 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.2% Tween 20, 1.6 M betaine, 2.8 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), and 1 μl of Bst DNA polymerase. Before the experiment, the LAMP primer mixture was premixed, and subsequently the reaction mixture and template DNA were added in. The reaction mixture was incubated in a real-time turbidimeter (LA320; Teramecs, Tokyo, Japan) at 63°C for 60 min, followed by 85°C for 5 min to terminate the reaction. Positive and negative samples were distinguished from one another by a turbidity cutoff value of 0.1. After amplification, the LAMP products were detected by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels with ethidium bromide staining or were determined by observing the color change after addition of 1 μl of 1,000× SYBR green I.

TABLE 2.

LAMP and qPCR primers used in this study to detect A. fumigatusa

| anxC4 assay type | Primer/probe name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMP assay | F3 | AGATACGGACGACGAGGC | 951–968 |

| B3 | TGACCGGGAATGTCCTCATC | 1165–1182 | |

| FIP | ATCTACGCGAGGCGAGGACGCTAGCGATCTGGAGCGTGAT | 990–1009, 1038–1058 | |

| BIP | GGTCCAGTTATGTCCGGGGCTGAAGCATGACGGGAACG | 1082–1102, 1145–1163 | |

| qPCR | F | CAGTGACGTATGAGAGTC | 914–931 |

| R | GGACATAACTGGACCATC | 1054–1071 | |

| Probe | CTACTCAGATACGGACGACGAG | 945–966 |

Underlining corresponds to the positions of target sequences.

FIG 1.

Names and locations of target sequences used as primers for the expression site of the anxC4 LAMP assay.

Reference plasmid.

In order to evaluate the sensitivity of the LAMP assay, a recombinant plasmid containing the target sequence of the anxC4 gene from the A. fumigatus strain (ATCC 13073) was constructed as follows: (i) a pair of primers was designed to span the sequences between the F3 and B3 primers: forward primer anxC4-F (5′-TCGCCAAATCTTCGACCAGT-3′) and reverse primer anxC4-R (5′-GGTCTGGCATAGCTGGGATG-3′); (ii) the PCR products (275 bp) were cloned into the pMD19-T vector using the pMD19-T vector cloning kit (TaKaRa Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan); and (iii) the recombinant plasmid was quantified with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) and was serially diluted (to concentrations of 0.5 × 107, 106, 105, 104, 103, 102, 101, and 1 copies/μl) in order to evaluate the limit of detection of the LAMP assay.

Evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of the LAMP assay.

In order to compare the sensitivities of the LAMP assay and qPCR, the serially diluted reference plasmids (at concentrations of 0.5 × 107, 106, 105, 104, 103, 102, 101, and 1 copies/μl) containing the target DNA sequence were used to evaluate the limit of detection. The detection limit of the reaction was evaluated by measuring the corresponding copy number of the plasmid DNA containing the anxC4 gene of A. fumigatus. A 2-μl sample was used in each reaction mixture. The qPCR assay was performed with the primers and probe in Table 2. qPCR amplification was performed in a 25-μl reaction volume containing 10 μM each primer, 10 μM probe, 2× Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan), and 2 μl of the DNA template. The assays were conducted using the qPCR settings of predenaturation at 95°C for 30 s, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 s, and extension at 59°C for 30 s in an Bio-Rad IQ5 real-time PCR instrument (Bio-Rad, Inc., USA). Fluorescence readings were acquired using the 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) channel. All detection assays were performed in triplicate. Genomic DNAs of the 22 non-A. fumigatus strains were detected by LAMP and qPCR to determine the specificity of the anxC4 LAMP assay and qPCR method.

Analysis of clinical samples using the LAMP and qPCR methods.

DNA extraction and preparation were performed using the improved CTAB extraction method. These DNA samples were analyzed using both the LAMP and qPCR methods as described above. A positive control using 1,000 copies of the plasmid containing the anxC4 gene and a negative control (nuclease-free water) were included in each run. The LAMP products were detected by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide, followed by visualization under UV light.

RESULTS

Specificity of the LAMP assay.

The specificities of the LAMP assay and the qPCR targeting of the anxC4 gene were tested with 1 A. fumigatus strain and 22 non-A. fumigatus strains (Table 1). Only positive amplification was observed in the A. fumigatus strain; in contrast, the 22 non-A. fumigatus strains were not amplified by either LAMP or qPCR. The result indicated that no false-positive amplifications were observed with these heterologous species in the LAMP assay developed, which had high specificity similar to that of qPCR.

Sensitivity of the LAMP assay.

The sensitivity of the LAMP assay was evaluated by testing 10-fold serial dilutions of plasmid DNA containing the anxC4 gene of A. fumigatus. The detection limits of the LAMP assay and qPCR for the anxC4 gene were 10 and 102 copies/reaction, respectively. This result indicated that the LAMP assay was more sensitive than qPCR for detecting A. fumigatus DNA.

Detection of clinical samples using the LAMP and qPCR.

In total, samples from 14 patients with probable IA and 55 patients with possible IA were tested by LAMP and qPCR. As demonstrated in Table 3, the 14 patients with probable IA (100%) were detected as positive by LAMP and qPCR. For the patients with possible IA, 34 (61.82%) were detected as positive by LAMP, but only 23 (41.82%) were positive by qPCR. This result indicated that LAMP may have higher sensitivity than qPCR in the present study. In addition, the results of detection of specimens by both the LAMP and qPCR methods were also compared. Table 4 shows that of the 69 total specimens, 48 (69.57%) were detected as positive by LAMP but only 37 (53.62%) by qPCR. Thirty-three positive samples and 17 negative samples were in agreement by both techniques, and their concordance rate was 72.46%. However, 15 samples found to be positive by LAMP were negative when tested by qPCR. Likewise, 4 samples found to be negative by LAMP were positive when tested by qPCR. Based on the results in Table 4, the comparative sensitivity and specificity of the LAMP assay were 89.19% (33/37) and 53.13% (17/32), respectively.

TABLE 3.

Detection results for patients with probable and possible IA using the LAMP and qPCR methods

| Detection method | No. of patients with probable IA (n = 14) | No. of patients with possible IA (n = 55) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMP assay | |||

| Positive | 14 | 34 | 48 |

| Negative | 0 | 21 | 21 |

| qPCR assay | |||

| Positive | 14 | 23 | 37 |

| Negative | 0 | 32 | 32 |

TABLE 4.

Comparative evaluation of the LAMP and qPCR methods for the detection of clinical samples

| LAMP assay result | No. (%) of samples with the following qPCR result: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 33 | 15 | 48 (69.57) |

| Negative | 4 | 17 | 21 |

| Total | 37 (53.62) | 32 | 69 |

DISCUSSION

A. fumigatus is a major etiological agent causing IA, the mortality rate of which is >50% (29, 30), Early diagnosis of A. fumigatus infection, however, continues to be problematic. Due to the lack of a rapid, sensitive, and effective diagnostic method, patients with serious infections usually cannot get timely and effective treatment, and this can lead to fatal outcomes.

So far, the traditional culturing method is the gold standard for A. fumigatus diagnosis, but it requires several days for observation of fungal growth and is time-consuming with low sensitivity. In addition, fungi are common laboratory contaminants, so the specificity of the culturing method is not satisfactory for the identification of the target microbes. Modified PCR-based techniques such as nested PCR and real-time quantitative PCR are usually complicated and require a high-precision thermal cycler, laboratory-scale instrumentation, and skilled personnel (9, 31). In contrast, the LAMP assay does not require sophisticated and expensive equipment; most importantly, maintenance of a constant temperature of 60 to 65°C for 1 h is sufficient for the amplification reaction (14). In this study, we chose the anxC4 gene as the target sequence for A. fumigatus detection, and the primers for the LAMP assay were designed on the basis of its conserved regions. The anxC4 gene has some discriminatory-informative single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that have been used in multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis (32). SNP markers have been applied for the detection and identification of Salmonella, Burkholderia cepacia, and A. fumigatus (32–34), so the variable anxC4 gene is suitable for use as a target for the detection and identification of A. fumigatus.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to use LAMP technology to detect A. fumigatus with high sensitivity and specificity. In total, we tested 22 non-A. fumigatus strains to evaluate the specificity of the anxC4 LAMP assay, and the result was 100% specificity. Through clinical analysis of cases, few could be identified as proven IA according to the EORTC/MSG diagnostic criteria. The main reason is that the EORTC/MSG diagnostic criteria for proven IA still rely heavily on histopathological evidence and traditional laboratory fungal culturing, which hampers early detection because in clinical practice many patients with suspected infection are too weak to undergo invasive procedures. In the present study, all patients with probable IA (100%) and 34 (61.82%) with possible IA were detected as positive by LAMP, and this validated the high sensitivity and specificity of this newly established LAMP method. For the 21 negative cases of the 55 patients with possible IA detected by LAMP, we think that the patients probably received antifungal drug therapy before sampling, thus leading to the false-positive clinical diagnosis (35). The comparison of the results of LAMP and qPCR detection on clinical samples showed that they had good concordance; besides simplicity, however, the detection limit and speed of the LAMP assay seemed better than those of qPCR for clinical samples. In addition, it has been reported that the sensitivity of molecular detection methods such as qPCR and LAMP is subject to a variety of factors present in clinical samples. For example, the multitude of drugs and fluids prescribed to patients at risk for IA can inhibit the qPCRs (36), while in comparison, the Bst polymerase in LAMP is more tolerant to these inhibitors than Taq polymerase in the amplification of the clinical samples (37), which might lead to better sensitivity for the LAMP assay.

In conclusion, we developed a LAMP assay for the rapid diagnosis of A. fumigatus and successfully validated its sensitivity and specificity in this study. Thus, this assay may serve as an effective method for the first-line detection and identification of A. fumigatus in clinical samples. Further study of a large number of patients with proven IA is needed to confirm the suitability of the LAMP assay developed here for future clinical application.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants 81172801 from the National Scientific Foundation Committee (NSFC), 2013CB531600 from the 973 Program from the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, 2015DFR31060 from the International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of China, 81273229 from the NSFC, and 2013ZX10004804-007 from National Key Program for Infectious Diseases of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kwon-Chung KJ, Sugui JA. 2013. Aspergillus fumigatus—what makes the species a ubiquitous human fungal pathogen? PLoS Pathog 9:e1003743. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ, Denning DW, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, van Burik JA, Wingard JR, Patterson TF, Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2008. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 46:327–360. doi: 10.1086/525258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliveira M, Lackner M, Amorim A, Araujo R. 2014. Feasibility of mitochondrial single nucleotide polymorphisms to detect and identify Aspergillus fumigatus in clinical samples. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 80:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clancy CJ, Jaber RA, Leather HL, Wingard JR, Staley B, Wheat LJ, Cline CL, Rand KH, Schain D, Baz M, Nguyen MH. 2007. Bronchoalveolar lavage galactomannan in diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis among solid-organ transplant recipients. J Clin Microbiol 45:1759–1765. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00077-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francesconi A, Kasai M, Petraitiene R, Petraitis V, Kelaher AM, Schaufele R, Hope WW, Shea YR, Bacher J, Walsh TJ. 2006. Characterization and comparison of galactomannan enzyme immunoassay and quantitative real-time PCR assay for detection of Aspergillus fumigatus in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from experimental invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 44:2475–2480. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02693-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Husain S, Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH, Swartzentruber S, Leather H, LeMonte AM, Durkin MM, Knox KS, Hage CA, Bentsen C, Singh N, Wingard JR, Wheat LJ. 2008. Performance characteristics of the platelia Aspergillus enzyme immunoassay for detection of Aspergillus galactomannan antigen in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Clin Vaccine Immunol 15:1760–1763. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00226-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musher B, Fredricks D, Leisenring W, Balajee SA, Smith C, Marr KA. 2004. Aspergillus galactomannan enzyme immunoassay and quantitative PCR for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis with bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J Clin Microbiol 42:5517–5522. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5517-5522.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh TJ, Wissel MC, Grantham KJ, Petraitiene R, Petraitis V, Kasai M, Francesconi A, Cotton MP, Hughes JE, Greene L, Bacher JD, Manna P, Salomoni M, Kleiboeker SB, Reddy SK. 2011. Molecular detection and species-specific identification of medically important Aspergillus species by real-time PCR in experimental invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 49:4150–4157. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00570-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuenca-Estrella M, Bassetti M, Lass-Florl C, Racil Z, Richardson M, Rogers TR. 2011. Detection and investigation of invasive mould disease. J Antimicrob Chemother 66(Suppl 1):i15−i24. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuenca-Estrella M, Meije Y, Diaz-Pedroche C, Gomez-Lopez A, Buitrago MJ, Bernal-Martínez L, Grande C, Juan RS, Lizasoain M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Aguado JM. 2009. Value of serial quantification of fungal DNA by a real-time PCR-based technique for early diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in patients with febrile neutropenia. J Clin Microbiol 47:379–384. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01716-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White PL, Bretagne S, Klingspor L, Melchers WJ, McCulloch E, Schulz B, Finnstrom N, Mengoli C, Barnes RA, Donnelly JP, Loeffler J, EAPCRI. 2010. Aspergillus PCR: one step closer to standardization. J Clin Microbiol 48:1231–1240. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01767-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castelli MV, Buitrago MJ, Bernal-Martinez L, Gomez-Lopez A, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M. 2008. Development and validation of a quantitative PCR assay for diagnosis of scedosporiosis. J Clin Microbiol 46:3412–3416. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00046-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernal-Martínez L, Buitrago MJ, Castelli MV, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M. 2012. Detection of invasive infection caused by Fusarium solani and non-Fusarium solani species using a duplex quantitative PCR-based assay in a murine model of fusariosis. Med Mycol 50:270–275. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2011.604047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Notomi T, Okayama H, Masubuchi H, Yonekawa T, Watanabe K, Amino N, Hase T. 2000. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 28:E63. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dinzouna-Boutamba SD, Yang HW, Joo SY, Jeong S, Na BK, Inoue N, Lee WK, Kong HH, Chung DI, Goo YK, Hong Y. 2014. The development of loop-mediated isothermal amplification targeting alpha-tubulin DNA for the rapid detection of Plasmodium vivax. Malar J 13:248. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das A, Babiuk S, McIntosh MT. 2012. Development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid detection of capripoxviruses. J Clin Microbiol 50:1613–1620. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06796-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill J, Beriwal S, Chandra I, Paul VK, Kapil A, Singh T, Wadowsky RM, Singh V, Goyal A, Jahnukainen T, Johnson JR, Tarr PI, Vats A. 2008. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid detection of common strains of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol 46:2800–2804. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00152-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng S, Xu J, Xiong Y, Ye C. 2012. Rapid and sensitive detection of Plesiomonas shigelloides by loop-mediated isothermal amplification of the hugA gene. PLoS One 7:e41978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuzawa T, Tanaka R, Horie Y, Gonoi T, Yaguchi T. 2010. Development of rapid and specific molecular discrimination methods for pathogenic emericella species. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi 51:109–116. doi: 10.3314/jjmm.51.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duan YB, Ge CY, Zhang XK, Wang JX, Zhou MG. 2014. Development and evaluation of a novel and rapid detection assay for Botrytis cinerea based on loop-mediated isothermal amplification. PLoS One 9:e111094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalaj V, Smith L, Brookman J, Tuckwell D. 2004. Identification of a novel class of annexin genes. FEBS Lett 562:79–86. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geisow MJ, Fritsche U, Hexham JM, Dash B, Johnson T. 1986. A consensus amino-acid sequence repeat in Torpedo and mammalian Ca2+-dependent membrane-binding proteins. Nature 320:636–638. doi: 10.1038/320636a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moss SE, Morgan RO. 2004. The annexins. Genome Biol 5:219. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-4-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khalaj V, Azarian B, Enayati S, Vaziri B. 2011. Annexin C4 in A. fumigatus: a proteomics approach to understand the function. J Proteomics 74:1950–1958. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas PG, Maertens J, Lortholary O, Kauffman CA, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Maschmeyer G, Bille J, Dismukes WE, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Kibbler CC, Kullberg BJ, Marr KA, Munoz P, Odds FC, Perfect JR, Restrepo A, Ruhnke M, Segal BH, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC, Viscoli C, Wingard JR, Zaoutis T, Bennett JE, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. 2008. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 46:1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ascioglu S, Rex JH, de Pauw B, Bennett JE, Bille J, Crokaert F, Denning DW, Donnelly JP, Edwards JE, Erjavec Z, Fiere D, Lortholary O, Maertens J, Meis JF, Patterson TF, Ritter J, Selleslag D, Shah PM, Stevens DA, Walsh TJ, Invasive Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and Mycoses Study Group of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 2002. Defining opportunistic invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplants: an international consensus. Clin Infect Dis 34:7–14. doi: 10.1086/323335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chong GL, van de Sande WW, Dingemans GJ, Gaajetaan GR, Vonk AG, Hayette MP, van Tegelen DW, Simons GF, Rijnders BJ. 2015. Validation of a new Aspergillus real-time PCR assay for direct detection of Aspergillus and azole resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J Clin Microbiol 53:868–874. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03216-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Omega Bio-tek. 2008. E.Z.N.A. high performance (HP) fungal DNA protocol. Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balloy V, Chignard M. 2009. The innate immune response to Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbes Infect 11:919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kousha M, Tadi R, Soubani AO. 2011. Pulmonary aspergillosis: a clinical review. Eur Respir Rev 20:156–174. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00001011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan ZU, Ahmad S, Theyyathel AM. 2008. Detection of Aspergillus fumigatus-specific DNA, (1-3)-beta-d-glucan and galactomannan in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage specimens of experimentally infected rats. Mycoses 51:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2007.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caramalho R, Gusmao L, Lackner M, Amorim A, Araujo R. 2013. SNaPAfu: a novel single nucleotide polymorphism multiplex assay for Aspergillus fumigatus direct detection, identification and genotyping in clinical specimens. PLoS One 8:e75968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ben-Darif E, Jury F, De Pinna E, Threlfall EJ, Bolton FJ, Fox AJ, Upton M. 2010. Development of a multiplex primer extension assay for rapid detection of Salmonella isolates of diverse serotypes. J Clin Microbiol 48:1055–1060. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01566-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ben-Darif E, De Pinna E, Threlfall EJ, Bolton FJ, Upton M, Fox AJ. 2010. Comparison of a semi-automated rep-PCR system and multilocus sequence typing for differentiation of Salmonella enterica isolates. J Microbiol Methods 81:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walsh TJ, Shoham S, Petraitiene R, Sein T, Schaufele R, Kelaher A, Murray H, Mya-San C, Bacher J, Petraitis V. 2004. Detection of galactomannan antigenemia in patients receiving piperacillin-tazobactam and correlations between in vitro, in vivo, and clinical properties of the drug-antigen interaction. J Clin Microbiol 42:4744–4748. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4744-4748.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ambasta A, Carson J, Church DL. 2015. The use of biomarkers and molecular methods for the earlier diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients. Med Mycol 53:531−557. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myv026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nie K, Qi SX, Zhang Y, Luo L, Xie Y, Yang MJ, Zhang Y, Li J, Shen H, Li Q, Ma XJ. 2012. Evaluation of a direct reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification method without RNA extraction for the detection of human enterovirus 71 subgenotype C4 in nasopharyngeal swab specimens. PLoS One 7:e52486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]