Abstract

Although a number of PCR-based quantitative assays for measuring HIV-1 persistence during suppressive antiretroviral therapy (ART) have been reported, a simple, sensitive, reproducible method is needed for application to large clinical trials. We developed novel quantitative PCR assays for cell-associated (CA) HIV-1 DNA and RNA, targeting a highly conserved region in HIV-1 pol, with sensitivities of 3 to 5 copies/1 million cells. We evaluated the performance characteristics of the assays using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 5 viremic patients and 20 patients receiving effective ART. Total and resting CD4+ T cells were isolated from a subset of patients and tested for comparison with PBMCs. The estimated standard deviations including interassay variability and intra-assay variability of the assays were modest, i.e., 0.15 and 0.10 log10 copies/106 PBMCs, respectively, for CA HIV-1 DNA and 0.40 and 0.19 log10 copies/106 PBMCs for CA HIV-1 RNA. Testing of longitudinally obtained PBMC samples showed little variation for either viremic patients (median fold differences of 0.80 and 0.88 for CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA, respectively) or virologically suppressed patients (median fold differences of 1.14 and 0.97, respectively). CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels were strongly correlated (r = 0.77 to 1; P = 0.0001 to 0.037) for assays performed using PBMCs from different sources (phlebotomy versus leukapheresis) or using total or resting CD4+ T cells purified by either bead selection or flow cytometric sorting. Their sensitivity, reproducibility, and broad applicability to small numbers of mononuclear cells make these assays useful for observational and interventional studies that examine longitudinal changes in the numbers of HIV-1-infected cells and their levels of transcription.

INTRODUCTION

Despite effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), curing HIV-1 infections remains a formidable challenge, because of the persistence of latently infected CD4+ T cells that are capable of producing infectious virus following proviral reactivation (1, 2). There is growing interest in using latency-reversing agents, therapeutic vaccines, broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, gene therapy, and a variety of other pharmacological and immunological approaches to control or to eliminate HIV-1 reservoirs (3–5). These therapeutic strategies require reliable inexpensive methods for assessment of their effects on measures of HIV-1 persistence in clinical studies (6).

One approach to assessing the efficacy of novel therapies is to determine changes in the numbers of HIV-1-infected cells and the transcriptional activity of those cells by measuring cell-associated (CA) HIV-1 DNA and CA HIV-1 RNA levels. Prior work showed that CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA remain detectable in most chronically infected individuals despite suppressive ART (7, 8). Although the association of CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels with the size of the latent HIV-1 reservoir has been called into question (9), recent studies suggest that CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels may predict the time to virological rebound after ART cessation and thus may serve as clinically relevant biomarkers (10, 11).

A number of real-time PCR-based assays to quantify total and/or various subspecies of CA HIV-1 DNA or RNA have already been described (12–16). The assays employ a wide variety of extraction methods, PCR conditions, and amplification targets, complicating comparisons between studies. In addition, some of those assays are labor-intensive or involve multiple rounds of PCR, which can complicate quantification and potentially lead to false-positive results. Our goal was to devise simple, sensitive, specific, and reproducible methods for HIV-1 DNA and unspliced HIV-1 mRNA measurements, to quantify the numbers of HIV-1-infected cells and proviral transcriptional activity.

We previously reported targeting a highly conserved region at the 3′ end of the pol gene for sensitive detection of HIV-1 RNA in plasma (17). We have now developed quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays for CA HIV-1 DNA (CAD) and unspliced mRNA (CAR), targeting the same 3′ region of pol. We addressed a number of performance characteristics of the CAD and CAR assays, including sensitivity, intra-assay and interassay variations, biological variations in longitudinal samples from the same donors, and correlations between assays performed using different sources of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and different methods of purification to total CD4+ (tCD4) and resting CD4+ (rCD4) T cells, as used in clinical studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimens.

All specimen donors were recruited from the University of Pittsburgh AIDS Center for Treatment (PACT) and provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board. The donors were enrolled consecutively in two groups, i.e., (i) viremic donors with detectable plasma viremia of >1,000 copies/ml at the time of enrollment, as measured by the Roche COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan v2.0 (TM2.0) assay, and (ii) virologically suppressed donors who had been receiving stable ART for at least 6 months, with plasma HIV-1 RNA levels suppressed to <20 copies/ml (Roche TM2.0). Since the assays were designed for non-subtype C group M HIV-1 viruses, only patients with subtype B HIV-1 infections were enrolled.

When available, samples were collected at two time points, separated by at least 10 days, through either large-volume phlebotomy (100 to 180 ml) or leukapheresis. Specimens were processed to PBMCs by Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) within 4 h, cryopreserved in aliquots of 5 to 10 million cells, and stored in liquid nitrogen. Plasma was obtained by centrifugation of blood at 400 × g for 10 min, followed by a second centrifugation of plasma at 1,350 × g for 15 min, harvesting of cell-free plasma, and storage at −80°C.

Low-copy-number HIV-1-infected cells.

Low-copy-number HIV-1-infected cells were obtained from the Virology Quality Assurance Program at Rush University Medical Center. Samples were prepared by seeding as few as 30 HIV-1-infected U1 cells (known to contain 2 proviral DNA copies/cell) into 1 million human-derived HIV-1-negative PBMCs. The nucleic acids were extracted, serially diluted to the expected endpoint, and assayed for CA HIV-1 DNA. For verification, the cells were also serially diluted to the expected endpoint, extracted, and assayed for CA HIV-1 DNA. Given that most HIV-1-infected cell lines do not produce stable amounts of CA HIV-1 RNA, we did not attempt to determine the limit of detection for the CAR assay using U1 cells.

Purification of total and resting CD4+ T cells.

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed in a 37°C bead bath, warm RPMI 1640 medium (Lonza, Switzerland) at 37°C with 50 units/ml Benzonase (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added dropwise, and then the mixture was centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min. After the liquid was removed, the cells were washed once with warm RPMI 1640 medium with Benzonase and were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% Gibco heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Enrichment for tCD4 and rCD4 cells was performed by negative selection using appropriate T cell isolation kits (Stemcell Technologies, Canada). Both tCD4 and rCD4 cells were found to be >90% pure (median, 97.1%) by flow cytometry.

A portion of the bead-enriched cells were labeled using CD3-V450, CD4-APC-H7, CD69-APC, CD25-PE, and HLA-DR-PerCP-Cy5.5 antibodies and were sorted on a BD FACSAria IIu system, to yield tCD4 and rCD4 cells of higher purity (>99%). The sorted cells, along with the rest of the bead-enriched CD4+ T cells, were snap-frozen and stored as cell pellets at −80°C before testing for CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA.

Quantification of cell-associated HIV-1 DNA and RNA. (i) Isolation of total cellular nucleic acids.

The methods for quantitation are summarized in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. The isolation of cellular nucleic acids was based on previously published methods (18). In brief, 100 μl of guanidinium hydrochloride with proteinase K (3 M guanidinium hydrochloride [Sigma-Aldrich, USA], 50 mM Tris·HCl [pH 7.6], 1 mM calcium chloride, 1 mg/ml proteinase K [Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA]) was added to pellets of 2.5 million cells. To ensure adequate cell lysis, the sample was sonicated for 10 s in a Branson Sonifier ultrasonic cell disruptor (Emerson, USA), at 50% amplitude in pulse mode. This was followed by a 1-h incubation at 42°C, followed by the addition of 400 μl of guanidinium thiocyanate with glycogen (6 M guanidinium thiocyanate [Sigma-Aldrich, USA], 50 mM Tris·HCl [pH 7.6], 1 mM EDTA, 600 μg/ml glycogen [Roche, Switzerland]). Samples were then incubated at 42°C for 10 min. Next, 500 μl of 100% isopropanol was added and nucleic acids were precipitated by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was then removed. The pellet was washed by the addition of 1 ml of 70% ethanol, brief vortex-mixing, and then centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 10 min. After the supernatant was removed, the pellet was allowed to air dry for 10 min; 36 μl of DNase incubation buffer (Roche, Switzerland) was then added, followed by another 10-s sonication, at 50% amplitude in pulse mode, to resuspend the pellet.

The nucleic acid extract was split into two equal 18-μl aliquots; one aliquot was frozen for downstream quantification of HIV-1 DNA, and the other was used for RNA purification. The latter was accomplished by 20 min of digestion with 20 units of recombinant RNase-free DNase I (Roche, Switzerland), addition of 200 μl of guanidinium thiocyanate (as above) without glycogen and then 250 μl of 100% isopropanol, and precipitation by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The pellet was washed by the addition of 1 ml 70% ethanol, brief vortex-mixing, and then centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 10 min. Ethanol was removed, and the pellet was air-dried for 10 min and resuspended in 70 μl of TDR solution (5 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1.0 μM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1,000 units/ml recombinant RNasin) for subsequent quantification of HIV-1 RNA.

(ii) Preparation of standards for HIV-1 DNA and RNA quantification.

The HIV-1 DNA standard was prepared by standard PCR using a primer set designed to amplify bases 4186 to 5913 of the HIV-1 reference sequence HXB2, with xxLAI (GenBank accession no. K02013) as the template. The PCR product was purified by gel electrophoresis, followed by gel extraction and cleanup with a QIAquick gel extraction kit and removal of unincorporated nucleotides using a nucleotide removal kit (Qiagen, Germany). The copy number of the purified standard was estimated on the basis of the optical density at 260 nm (OD260) and was further evaluated by serial dilution to an endpoint of 1 copy per PCR. At a nominal input of 1 copy per PCR, 40% to 70% of reactions were positive, consistent with the results expected from Poisson probability calculations for 1 copy per reaction. Once validated, the DNA standard was diluted to 1,000 copies/μl in Tris (pH 8.0) and stored in 20-μl aliquots at −80°C.

The preparation of the RNA standard was described previously (17). Briefly, HIV-1 RNA transcripts were transcribed in vitro from a T7 expression plasmid containing a 1.7-kb insert containing the 3′ end of pol. Transcripts were subjected to multiple rounds of purification using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Germany), quantified on the basis of the OD260 (Implen NanoPhotometer), and subjected to serial endpoint dilution to 1 copy per PCR. At an input of 1 copy per reaction, 40% to 70% of reactions were positive. The RNA transcripts were diluted to 1,000 copies/μl in TDR solution (5 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1.0 μM DTT, 1,000 units/ml recombinant RNasin) and stored in 20-μl aliquots at −80°C.

(iii) Quantification of total cell-associated HIV-1 DNA.

The total nucleic acid extract (18 μl) was brought to a volume of 70 μl with the addition of 5 mM Tris. Total nucleic acid amounts were first estimated on the basis of the OD260 (Implen NanoPhotometer). The extract was diluted as needed to a concentration of ≤170 ng/μl, to prevent inhibition of PCR by excess nucleic acids. CA HIV-1 DNA was then quantified using real-time PCR, by testing 10 μl of DNA extract in triplicate in a total PCR volume of 25 μl containing the LightCycler 480 Probes Master ready-to-use reaction mixture with 400 nM forward and reverse primers and 200 nM probe designed to target the integrase region of pol (17). The cycling parameters were 95°C for 5 min and then 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 1 min for 45 cycles of amplification. For quantification of CA HIV-1 DNA, a standard curve was prepared for each assay by serial 3-fold dilution of the HIV-1 DNA standard.

To assess the number of cell equivalents assayed in a PCR, 5 μl of nucleic acid extract was diluted 1:30 and then quantified in duplicate by qPCR for the CCR5 gene, according to a previously published protocol (13). CCR5 DNA standards were diluted from TaqMan control genomic DNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to generate a standard curve. CCR5 copy numbers were used to calculate HIV-1 DNA copies per 1 million cells. Results were further normalized, as appropriate, with respect to the percentages of total and resting CD4+ T cells determined by flow cytometry.

(iv) Quantification of cell-associated unspliced HIV-1 RNA.

CA HIV-1 RNA was quantified using a two-step quantitative real-time PCR assay. Total RNA amounts were first estimated on the basis of the OD260 (Implen NanoPhotometer). The samples were then diluted as needed to a concentration of ≤30 ng/μl, to prevent inhibition by excess RNA. RNA was used to generate cDNA, by using the AffinityScript multiple temperature reverse transcriptase (Agilent, USA), from 10 μl of RNA extract in five separate reactions. A no-reverse transcriptase control reaction was run concurrently, to screen for HIV-1 DNA contamination.

For real-time PCR, the LightCycler 480 Probes Master reaction mixture with specific primers and probes was added to make up a total PCR volume of 50 μl, with 400 nM forward and reverse primers and 200 nM probe. The cycling parameters for qPCR were 95°C for 5 min and then 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 1 min for 45 cycles of amplification. Two of five cDNA reactions were used to test the cellular housekeeping gene IPO8, which served as an internal control for mRNA recovery and was chosen because of its stable expression in a variety of blood cell types, including resting and activated lymphocytes (19). Samples with <25% expected recovery were excluded from analysis. The sequences of the primers and probe for IPO8 qPCR were reported previously (17).

The other three cDNA reactions were used for quantification of CA HIV-1 RNA, using the same HIV-1 pol primers and probe as for CA HIV-1 DNA. Of note, the region targeted by the primer/probe set is also represented by vif mRNA, in addition to unspliced HIV-1 mRNA. However, since vif mRNA represents only 0.21% of the 4-kb family of singly spliced HIV-1 mRNAs in CD4+ T cells (20), this is not expected to bias the measurement of unspliced mRNA significantly. For CA HIV-1 RNA quantification, a standard curve for CA HIV-1 RNA was generated with each assay. Sample values derived from the standard curve were normalized to HIV-1 RNA copies per 1 million cells by using CCR5 copy numbers.

Quantification of plasma HIV-1 RNA.

Plasma HIV-1 RNA was quantified with a qPCR assay targeting the 3′ end of integrase with single-copy sensitivity, as reported previously (17).

Flow cytometric analysis.

The purities of isolated tCD4 and rCD4 cells were assessed by analyzing the surface expression of T cell and activation markers using CD3-V450, CD4-APC-H7, CD69-APC, CD25-PE, and HLA-DR-PerCP-Cy5.5 antibodies. All antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences. All cells were fixed before analysis by using BD Cytofix buffer. A BD LSRFortessa cytometer with FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) was used to acquire and to analyze the results.

Statistical analysis.

Plasma HIV-1 RNA (single-copy assay [SCA]) and CA HIV-1 RNA levels reported as less than the lower limit of detection were analyzed as one-half of the corresponding limit of detection. All analyses of total or resting CD4+ T cells were performed using CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels adjusted for cell purity, defined as measured CA HIV-1 DNA or RNA levels divided by the corresponding proportions of tCD4 and rCD4 cells. Parallel analyses were also performed without adjustment for cell purity.

The sensitivity of the CAD assay was validated using limiting dilutions of low-copy-number HIV-1-infected cells, followed by analysis using the maximum likelihood estimate, which employs a generalized linear model with a binomial distribution and a log link function in R (18). The intra-assay variability and interassay variability of the assay were assessed by comparing variance components. To assess the agreement between the two time points as well as measurements in cells obtained with different cell purification methods and/or collection methods, correlations of CA HIV-1 RNA and DNA were assessed using Spearman rank-based correlation coefficients.

RESULTS

Volunteers and samples.

Samples were obtained from 25 volunteers, including 5 viremic individuals not receiving ART and 20 virologically suppressed individuals receiving combination ART. All viremic participants and 18 suppressed participants provided samples at two time points, separated by a median of 34 days (range, 12 to 106 days). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the donors at the time of the first sample collection. The virologically suppressed group had a median CD4+ T cell count of 635 cells/mm3 (range, 386 to 1,667 cells/mm3) after a median of 5.4 years (range, 0.1 to 16.2 years) of suppressive ART; the median nadir CD4+ T cell count was 231 cells/mm3 (range, 23 to 578 cells/mm3). For the viremic group, the median CD4+ T cell count at the time of sample collection was 870 cells/mm3 (range, 224 to 1,053 cells/mm3) and the median nadir CD4+ T cell count was 692 cells/mm3 (range, 195 to 854 cells/mm3).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Subject | Sample collected | Age (yr) | Gender | Racea | Nadir CD4+ T cell level (cells/mm3) | Pre-ART plasma HIV-1 RNA level (copies/ml) | Duration of suppression on ART (yr) | Current CD4+ T cell level (cells/mm3) | Current proportion of CD4+ T cells (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virally suppressed subjects | |||||||||

| ART1 | Blood | 59 | Male | C | 80 | 15,883 | 8.1 | 486 | 24 |

| ART2 | Blood | 59 | Male | AA | 314 | 117,068 | 16.0 | 934 | 37 |

| ART3 | Blood | 52 | Male | C | 153 | 99,985 | 16.2 | 450 | 26 |

| ART4 | Blood | 46 | Female | C | 272 | 9,740 | 2.4 | 628 | 29 |

| ART5 | Blood | 45 | Female | AA | 143 | 142,157 | 1.4 | 810 | 35 |

| ART6 | Blood | 60 | Male | AA | NA | NA | NA | 416 | 25 |

| ART7 | Blood | 56 | Female | AA | 410 | 366,200 | 12.1 | 1,373 | 55 |

| ART8 | Blood | 42 | Male | AA | 323 | 90,437 | 0.1 | 606 | 32 |

| ART9 | Blood | 54 | Male | AA | NA | NA | NA | 607 | 35 |

| ART10 | Blood/Leukopak | 26 | Male | AA | 336 | 11,143 | 0.8 | 835 | 40 |

| ART11 | Leukopak | 59 | Male | C | 227 | 101,000 | 5.4 | 392 | 35 |

| ART12 | Leukopak | 45 | Male | C | 230 | 94,000 | 6.0 | 642 | 39 |

| ART13 | Leukopak | 57 | Male | C | 578 | 5,449 | 2.1 | 416 | 25 |

| ART14 | Leukopak | 43 | Male | C | 62 | 803,000 | 1.0 | 831 | 48 |

| ART15 | Leukopak | 50 | Male | C | 64 | 39,300 | 2.7 | 386 | 30 |

| ART16 | Leukopak | 44 | Female | AA | 277 | NA | NA | 1,667 | 43 |

| ART17 | Leukopak | 46 | Male | AA | 23 | 94,400 | 3.5 | 679 | 34 |

| ART18 | Leukopak | 52 | Male | C | 337 | 233,000 | 6.0 | 816 | 46 |

| ART19 | Leukopak | 51 | Male | C | 89 | 84,084 | 7.0 | 592 | 43 |

| ART21 | Leukopak | 52 | Female | AA | 231 | 11,454 | 15.8 | 821 | 45 |

| Median | 231 | 94,000 | 5.4 | 635 | 35 | ||||

| Viremic subjects without antiretroviral treatment | |||||||||

| VIR1 | Blood | 29 | Male | H | 854 | 2,165 | 749 | 37 | |

| VIR2 | Blood | 52 | Male | AA | 195 | 91,209 | 224 | 13 | |

| VIR3 | Blood | 54 | Male | AA | 677 | 2,185 | 1,053 | 45 | |

| VIR4 | Blood | 53 | Male | AA | 746 | NA | 874 | 28 | |

| VIR5 | Blood | 44 | Male | AA | 692 | NA | 870 | 17 | |

| Median | 692 | 2,185 | 870 | 28 |

AA, African American; C, Caucasian; H, Hispanic; NA, not tested or information not available.

Performance characteristics of the assays.

The sensitivities of CAD and CAR assays were determined by testing limiting dilutions of HIV-1 DNA standards and RNA transcripts. In accordance with the Poisson probability distribution, the assays were able to detect 3 copies of HIV-1 DNA or RNA standards in 80% to 100% of PCRs and 1 copy of HIV-1 standards in 40% to 70% of reactions (data not shown).

We determined the limit of detection of the CAD assay by testing serial dilutions of low-copy-number HIV-1-infected cells at 30 U1 cells (or 60 copies of HIV-1 DNA) per 1 million PBMCs. We first serially diluted the cells in 6 replicates before extraction. As expected, progressively fewer replicates were positive for HIV-1 DNA by PCR at higher cell dilutions (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Using the maximum likelihood calculation, we estimated 36 cells to be present per 1 million PBMCs, similar to the nominal value of 30 cells/1 million PBMCs for the preparation. We repeated the analysis by diluting extracted nucleic acids from 30 U1 cells/1 million PBMCs and testing 10 replicates at each dilution. Again, as expected, progressively fewer PCRs were positive for HIV DNA at higher dilutions (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The maximum likelihood estimate was 52 copies of HIV-1 DNA per 1 million PBMCs, close to the nominal value of 60 copies/1 million PBMCs for the preparation. Because of variable HIV-1 RNA expression per U1 cell or other infected cell lines, we were not able to use a similar approach to determine the limit of detection of the CAR assay.

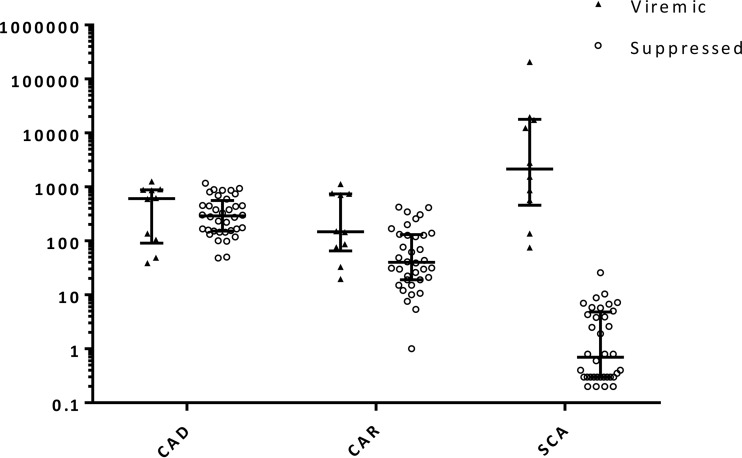

We then performed CAD and CAR assays using clinical samples from both viremic and virologically suppressed individuals. The results are summarized in Table 2. CA HIV-1 DNA was detected in 46 of 46 PBMC samples (median for viremic group, 2.78 log10 copies/106 PBMCs; median for suppressed group, 2.46 log10 copies/106 PBMCs). CA HIV-1 RNA was detected from 45 of 46 PBMC samples (median for viremic group, 2.17 log10 copies/106 PBMCs; median for suppressed group, 1.60 log10 copies/106 PBMCs) (Fig. 1). When CA HIV-1 RNA levels were ≤3 copies/106 PBMCs PCR detection became inconsistent. This lower limit of detection could be increased by extracting greater numbers of cells and increasing the number of PCR replicates tested. For example, doubling the number of cells tested for the one sample in which the CA HIV-1 RNA level was initially below the limit of detection revealed the CA HIV-1 RNA level to be ∼1 copy/106 PBMCs. In contrast, no false-positive results were obtained by CAD and CAR assays using HIV-1-negative samples, including MOLT4 CCR5+ and TZM-bl cell lines and 10 PBMC samples obtained from HIV-1-negative donors (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Summary of assay results for longitudinal PBMC samples

| Parameter | Viremic group |

Suppressed group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First time point (n = 5) | Second time point (n = 5) | Overall (n = 10) | First time point (n = 18) | Second time point (n = 18) | Overall (n = 36) | |

| CA HIV-1 DNA level (log10 copies/106 PBMCs) (median [range]) | 2.94 (1.68–3.10) | 2.78 (1.59–2.94) | 2.78 (1.59–3.10) | 2.41 (1.68–2.95) | 2.48 (1.99–3.07) | 2.46 (1.68–3.07) |

| CA HIV-1 RNA level (log10 copies/106 PBMCs) (median [range]) | 2.18 (1.51–3.05) | 2.16 (1.29–2.88) | 2.17 (1.29–3.05) | 1.70 (0.00–2.63)a | 1.54 (0.73–2.62) | 1.60 (0.00–2.63)a |

| CA HIV-1 RNA/DNA ratio (median [range]) | 0.83 (0.17–1.78) | 0.87 (0.14–1.97) | 0.85 (0.14–1.97) | 0.27 (0.02–0.71) | 0.16 (0.03–0.44) | 0.18 (0.02–0.71) |

| Plasma HIV-1 RNA level (log10 copies/ml) (median [range]) | 3.44 (2.75–5.32) | 3.19 (1.88–4.29) | 3.31 (1.88–5.32) | −0.16 (−0.70 to 1.41) | −0.31 (−0.70 to 1.02) | −0.16 (−0.70 to 1.41) |

One sample was below the limit of detection.

FIG 1.

Levels of proviral HIV-1 DNA and unspliced cellular HIV-1 RNA in PBMCs and HIV-1 RNA in plasma. Long horizontal lines, median values; short horizontal lines, first and third quartile values. CA HIV-1 RNA and plasma HIV-1 RNA levels less than the lower limit of detection are represented as one-half of the corresponding limit of detection. CAD, cell-associated HIV-1 DNA (copies/106 PBMCs); CAR, cell-associated HIV-1 RNA (copies/106 PBMCs); SCA, plasma HIV-1 RNA as determined by single-copy assay (copies/ml).

Intra-assay and interassay variations.

The intra-assay variabilities of the CAD and CAR assays were evaluated by simultaneously testing multiple replicates of samples from the same volunteers and time points (Table 3). Four participants provided data with 5 replicates each and the standard deviation was estimated, which includes intra-assay variability and variability between participants. For CA HIV-1 DNA, the estimated standard deviation including intra-assay variability was 0.1 log10 copies/106 PBMCs. For CA HIV-1 RNA, the estimated standard deviation was 0.19 log10 copies/106 PBMCs.

TABLE 3.

Intra-assay variability of CAD and CAR assays

| Parametera | Total | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Intra-assay variability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAD assay | ||||||

| No. of replicates | 20 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| DNA level (log10 copies/106 PBMCs) | 0.1 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.2 (1.9–2.6) | 2.1 (2.1–2.1) | 2.3 (2.3–2.4) | 2.8 (2.8–2.9) | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | |

| CAR assay | ||||||

| No. of replicates | 20 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| RNA level (log10 copies/106 PBMCs) | 0.19 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–2.1) | 2.0 (1.9–2.0) | 2.1 (2.1–2.2) | 2.0 (2.0–2.2) | 0 (0–0) |

CAD, cell-associated HIV-1 DNA; CAR, cell-associated HIV-1 RNA; IQR, interquartile range.

Interassay variabilities of the CAD and CAR assays were assessed by repeated testing of PBMC samples from the same 12 virally suppressed individuals at different times (Table 4). For CA HIV-1 DNA, the estimated standard deviation including interassay variability was 0.15 log10 copies/106 PBMCs. For CA HIV-1 RNA, the estimated standard deviation was higher, at 0.4 log10 copies/106 PBMCs.

TABLE 4.

Interassay variability of CAD and CAR assays

| Parametera | Total | Time 1 | Time 2 | Interassay variability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAD assay | ||||

| No. of samples | 24 | 12 | 12 | |

| DNA level (log10 copies/106 PBMCs) | 0.15 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.1 (1.9–2.5) | 2.2 (1.9–2.5) | 2.1 (1.9–2.4) | |

| CAR assay | ||||

| No. of samples | 24 | 12 | 12 | |

| RNA level (log10 copies/106 PBMCs) | 0.4 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | |

| Median (IQR) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 1.5 (0.9–1.8) | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) |

CAD, cell-associated HIV-1 DNA; CAR, cell-associated HIV-1 RNA; IQR, interquartile range.

Because different participants contributed to the two data sets used to calculate the intra-assay and interassay variabilities, it was not appropriate to conduct a formal statistical comparison. It appears, however, that the estimated standard deviation including interassay variability is larger than that including intra-assay variability.

Longitudinal variations in CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels among PBMCs.

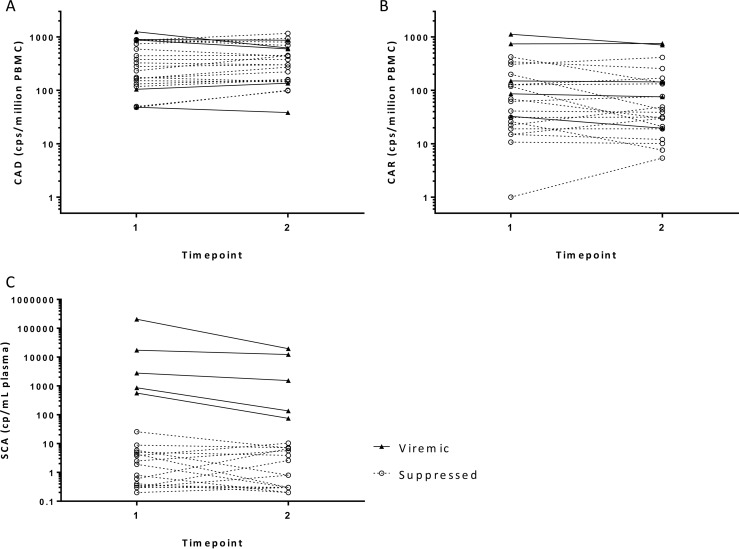

The in vivo longitudinal variations in CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels were determined by testing PBMC samples collected at two time points from 5 viremic individuals and 18 virologically suppressed individuals (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The median time between the two measurements was 34 days (range, 12 to 106 days). The samples were collected either by large-volume phlebotomy or by leukapheresis. Table 2 summarizes CA HIV-1 RNA and DNA levels, CA RNA/DNA ratios, and SCA values at the two time points.

FIG 2.

Short-term variations in levels of proviral HIV-1 DNA and unspliced RNA in PBMCs and HIV-1 RNA in plasma collected at two time points. (A) Short-term variations in CA HIV-1 DNA (CAD) levels in cryopreserved PBMCs. (B) Short-term variations in CA HIV-1 RNA (CAR) levels in cryopreserved PBMCs. (C) Short-term variations in HIV-1 RNA levels in plasma (SCA). Solid lines, viremic samples; dashed lines, virologically suppressed samples. cps or cp, copies.

Both CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels in viremic and virologically suppressed groups appeared to be mostly stable over the time period studied. Among the suppressed participants, the median CA HIV-1 DNA levels were 2.41 and 2.48 log10 copies/106 PBMCs for the first and second time points, respectively, and 94% of the participants had ≤2-fold changes over time. The median CA HIV-1 RNA levels were 1.70 and 1.54 log10 copies/106 PBMCs, and 61% of the participants showed ≤2-fold changes. Among the viremic participants, the median CA HIV-1 DNA levels were 2.94 and 2.78 log10 copies/106 PBMCs at the two time points, with 80% of the participants showing ≤2-fold changes. The corresponding median CA HIV-1 RNA levels were 2.18 and 2.16 log10 copies/106 PBMCs, and all of the participants had ≤2-fold changes. When the groups were examined together, the CA HIV-1 DNA, CA HIV-1 RNA, and plasma HIV-1 RNA measurements from samples obtained at the two time points were highly correlated by rank-based correlations, with CA HIV-1 DNA levels showing the greatest correlation coefficient (CA HIV-1 DNA, r = 0.924; CA HIV-1 RNA, r = 0.871; plasma HIV-1 RNA, r = 0.763; P < 0.0001) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Given the small sample size and divergent clinical characteristics, a formal comparison between the viremic and suppressed groups cannot be made. However, it is striking to note that, despite a 4-log-unit difference in the median plasma HIV-1 RNA levels between the viremic and suppressed groups, the median CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels in the same two groups differed by <1 log10 unit (CA HIV-1 DNA, 0.32 log10 copies/106 PBMCs; CA HIV-1 RNA, 0.57 log10 copies/106 PBMCs). The median CA HIV-1 RNA/DNA ratio appeared higher for the viremic group (ratio, 0.85) than for the virologically suppressed group (ratio, 0.18), reflecting higher HIV-1 transcriptional activities in the absence of ART.

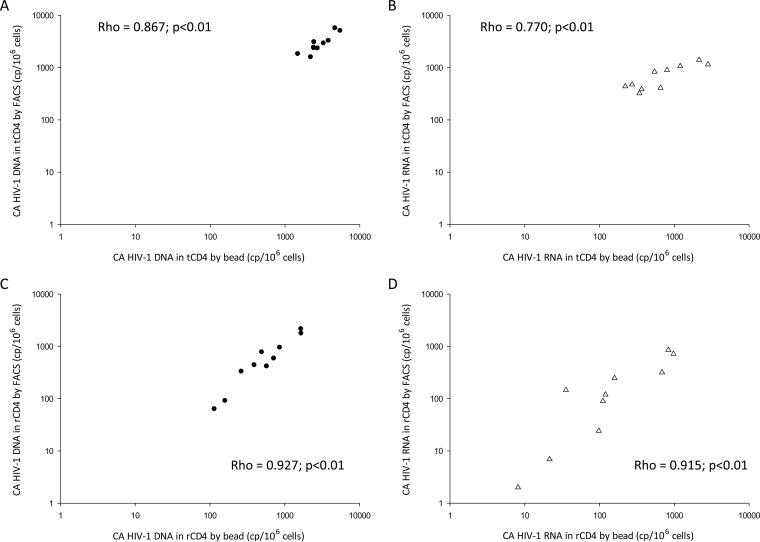

Correlations of CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels in CD4+ T cells purified by different methods.

A variety of cell purification methods have been used to process clinical samples. Although fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) is the gold standard for isolating total and resting CD4+ T cells from PBMCs with extremely high cell purity (>99%), commercial cell isolation kits using negative selection provide an inexpensive and efficient alternative. Therefore, we examined the effects of these different methods on CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA measurements.

Samples for total CD4+ T cell comparisons were obtained from 5 virologically suppressed individuals through large-volume phlebotomy performed at 2 time points. Due to the small numbers of participants contributing to the analysis, repeated measurements were treated as independent samples. Both FACS and tCD4 cell isolation kits provided tCD4 cells with good purities (medians of 99.8% and 96.1%, respectively). In this comparison, CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels adjusted for tCD4 cell purity were highly correlated for the two cell purification methods (CA HIV-1 DNA, r = 0.867; CA HIV-1 RNA, r = 0.770; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A and B; see Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material for the corresponding Bland-Altman plots).

FIG 3.

Correlations between HIV-1 DNA and HIV-1 RNA results according to cell purification method, i.e., beads alone versus beads plus sorting. (A) Correlation of CA HIV-1 DNA levels in tCD4 cells isolated by negative selection alone (bead) versus tCD4 cells isolated by negative selection followed by FACS. (B) Correlation of CA HIV-1 RNA levels in tCD4 cells isolated by beads versus tCD4 cells isolated by FACS. (C) Correlation of CA HIV-1 DNA levels in rCD4 cells isolated by beads versus rCD4 cells isolated by FACS. (D) Correlation of CA HIV-1 RNA levels in rCD4 cells isolated by beads versus rCD4 cells isolated by FACS. Long dashed lines, CA HIV-1 DNA; short dashed lines, CA HIV-1 RNA. cp, copies.

Samples for resting CD4+ T cell comparisons were obtained from 5 individuals through leukapheresis performed at 2 time points. Again, both FACS and tCD4 cell isolation kits provided rCD4 cells with high purities (medians of 99.9% and 99.6%, respectively). CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels adjusted for rCD4 cell purity were highly correlated for the two cell purification methods (CA HIV-1 DNA, r = 0.927; CA HIV-1 RNA, r = 0.915; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3C and D; see Fig. S2C and D in the supplemental material for the corresponding Bland-Altman plots). Analyses were also performed without adjustment for total or resting CD4+ T cell purity and did not show any difference (data not shown).

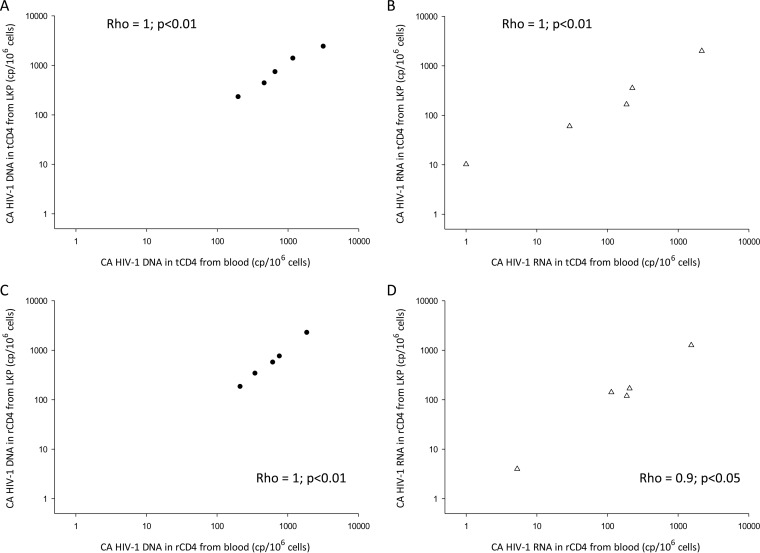

Correlations of CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels in CD4+ T cells collected by different methods.

We were also interested in studying the effects on CAD and CAR assay results of various methods of PBMC collection that are used in clinical studies. Although leukapheresis can yield large amounts of cells for various virological assays, costs and patient discomfort have limited its use for clinical trials. In addition, it was shown previously that continuous-flow leukapheresis may induce expression of stress genes in lymphocytes (21), raising concerns about HIV-1 proviral expression levels with leukapheresis.

We assessed samples collected from 5 participants through both leukapheresis and large-volume phlebotomy. Total and resting CD4+ T cells were isolated with appropriate commercial kits and showed good purities (medians of 94.4% and 97.5%, respectively). CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels adjusted for CD4+ T cell purity were found to be highly correlated (r = 0.9 to 1.0) for the two harvest methods in both cell types (Fig. 4; see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material for the corresponding Bland-Altman plots).

FIG 4.

Correlations between HIV-1 DNA and HIV-1 RNA results according to collection method, i.e., leukapheresis versus phlebotomy. (A) Correlation of CA HIV-1 DNA levels in tCD4 cells from leukapheresis (LKP) versus tCD4 cells from large-volume phlebotomy (blood). (B) Correlation of CA HIV-1 RNA levels in tCD4 cells from leukapheresis versus tCD4 cells from blood. (C) Correlation of CA HIV-1 DNA levels in rCD4 cells from leukapheresis versus rCD4 cells from blood. (D) Correlation of CA HIV-1 RNA levels in rCD4 cells from leukapheresis versus rCD4 cells from blood. Long dashed lines, CA HIV-1 DNA; short dashed lines, CA HIV-1 RNA. cp, copies.

DISCUSSION

We describe here two novel assays that are performed in conjunction to quantify both cellular HIV-1 DNA and unspliced HIV-1 RNA levels. The novel features of the assays include targeting of conserved HIV-1 sequences, the requirement for only one round of PCR, and an internal control for total amplifiable cellular mRNA (IPO8). The assays are sensitive, being capable of reliably detecting 3 to 5 copies of HIV-1 DNA or RNA per 1 million cells in as few as 2 million cells. The sensitivity of the assays can be further increased by extracting more cells and performing more replicates of PCR. Importantly, both the CA HIV-1 DNA and CA HIV-1 RNA assays showed modest intra-assay and interassay variabilities (0.15 and 0.10 log10 copies/106 PBMCs for CA HIV-1 DNA and 0.40 and 0.19 log10 copies/106 PBMCs for CA HIV-1 RNA, respectively) and limited biological variation in vivo.

The CAD and CAR assays described here offer a number of advantages over other reported assays. First, our assay targets a highly conserved region of the HIV-1 genome at the 3′ end of pol. Analysis of sequences from the Los Alamos database shows this region to be among the most highly conserved regions of the HIV-1 genome; therefore, primers and probes targeting this region should efficiently amplify samples from the greatest numbers of patients (17). Second, both DNA and RNA are quantified directly using real-time PCR, reducing errors that may be introduced in multistep quantitative assays (such as nested and seminested PCR assays) without sacrificing the sensitivity of detection. Another safeguard against testing errors is provided by targeting of the same nucleic acid amplicon from the same samples for both HIV-1 DNA and RNA measurements. As real-time PCR-based quantitative assays, CAD and CAR assays also avoid the pitfall of false-positive results, which are commonly reported for digital droplet PCR assays (22, 23). Repeated testing of HIV-1-negative cell lines and donor samples revealed no evidence of cross-reaction with human genomic DNA or RNA. Given the performance characteristics described above, CAD and CAR assays are suitable tools to quantify HIV-1-infected cells and transcriptional activities in large clinical trials.

Using CAD and CAR assays, we found that CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels are both relatively stable, in the absence of intervention, among virologically suppressed individuals. This finding is consistent with studies that showed a plateauing of HIV-1 DNA levels beyond 4 years of treatment (7). In addition, it suggests that the levels of HIV-1 transcription are stable in the short term. These results indicate that the assays are suitable for measuring the effects of clinical interventions aimed at eliminating HIV-1-infected cells.

We also performed extensive evaluations of the correlations between CAD and CAR assays performed with samples obtained through different methods of cell collection and cell purification that are commonly used in clinical trials of therapeutic strategies to cure HIV-1. Although FACS provides the highest purity of total and resting CD4+ T cells, the cost is prohibitive for large-scale clinical studies. Although it is reasonable to expect that, since CD4+ T cells are the main targets of HIV-1 infection, CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA levels normalized for CD4+ T cells should produce similar results, it is not known whether different methods of cell manipulation affect the measurements of HIV-1 DNA and RNA. Our findings show that, although measurements of CA HIV-1 DNA and RNA purified through different means did not agree perfectly with each another (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), they were strongly correlated (Fig. 3). This confirms that the less expensive CD4+ T cell isolation kits, which have already been used in a number of clinical studies (24, 25), are acceptable alternatives to FACS. In addition, since large numbers of cells are not needed for the CAD and CAR assays, phlebotomy provides a reasonable alternative to leukapheresis by providing a less resource-demanding alternative means of PBMC collection. These findings should help clinical investigators optimize resources in clinical trials. However, our results have also raised an important consideration, i.e., comparisons between trials utilizing different cell collection and processing methods should be undertaken with caution.

Although we validated the assays only with subtype B HIV-1, our analysis based on the Los Alamos HIV-1 sequence database shows that our primer/probe set is broadly applicable to all non-subtype C HIV-1 types among group M viruses. In addition, just one nucleotide substitution in the forward primer is needed for the application of CAD and CAR assays to subtype C viruses. Our initial experience is limited but, when we evaluated subtype C HIV-1-infected clinical samples, with appropriate modifications, we were able to detect and to quantify HIV-1 DNA and RNA reliably when evidence of subtype C infection was noted (data not shown). We are also evaluating the performance of degenerate forward primers, to broaden the application of this assay to all group M HIV-1 viruses.

Although the CAD and CAR assays provide reproducible measurements of HIV-1-infected cells and general transcriptional activity, they have some limitations. The CAD assay does not distinguish various species of integrated or nonintegrated HIV-1 DNA during active HIV-1 replication, and it does not provide accurate measurements of intact HIV-1 proviruses that are capable of being activated to produce functional virions. In addition, HIV-1 proviruses with mutations affecting the 3′ end of pol, including large internal deletions, would not be detected by the CAD assay. Such vestiges of HIV-1 infection, i.e., integrated HIV-1 proviruses rendered inactive due to mutations or deletions, may be better addressed by measuring the long terminal repeat (LTR) region in the HIV-1 genome.

Such limitations also extend to measurements of CA HIV-1 RNA. The CAR assay is not designed to distinguish between unspliced HIV-1 mRNA and pol-containing chimeric readthrough transcripts resulting from host gene transcription. However, one study suggested that readthrough transcripts are a minor species, in comparison to unspliced HIV-1 mRNA, among virologically suppressed patients (26). The CAR assay also does not measure singly and multiply spliced HIV-1 mRNA species and therefore is unsuitable for investigating different stages of HIV-1 RNA processing.

In addition, the CAR assay does not provide a measure of the fraction of HIV-1-infected cells that are actively transcribing HIV-1 mRNA. An alternative approach using limiting dilution and maximum likelihood estimation, as described elsewhere for cells in culture (18), will be needed to provide data on fractional proviral expression in vivo. Additional assays will be required to determine the proportions of cells expressing CA HIV-1 RNA that are also producing viral proteins, virions, and infectious virions. All of these issues illustrate the need for continued assay development in support of different applications.

In summary, we report the performance characteristics of sensitive precise assays to detect and to quantify total CA HIV-1 DNA and unspliced HIV-1 RNA. By monitoring changes in HIV-1 proviruses and levels of cellular HIV-1 transcription, the CAD and CAR assays supplement the information provided by the single-copy assay measuring plasma HIV-1 RNA levels and can be employed as a useful tool in observational studies examining the long-term changes of HIV-1-infected cells, as well as in interventional studies aimed at reducing the numbers of infected cells and their transcriptional activity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge grant support from the NCI through Leidos (grant 25XS119), from the AIDS Clinical Trials Group to the Pittsburgh Virology Specialty Laboratory (NIH grant AI068636), from the NIAID Virology Quality Assurance Program (grant HHSN272201200023C), and from the Statistical and Data Management Center of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (NIH grant AI068634).

J.W.M. is a consultant to Gilead Sciences and holds share options in Cocrystal Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; no other conflicts are reported. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

We thank the volunteers for donating their blood for this study. We also thank Lorraine Pollini for proofreading the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02904-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, Carruth LM, Buck C, Chaisson RE, Quinn TC, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Brookmeyer R, Gallant J, Markowitz M, Ho DD, Richman DD, Siliciano RF. 1997. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278:1295–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siliciano JD, Kajdas J, Finzi D, Quinn TC, Chadwick K, Margolick JB, Kovacs C, Gange SJ, Siliciano RF. 2003. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat Med 9:727–728. doi: 10.1038/nm880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Passaes CP, Sáez-Cirión A. 2014. HIV cure research: advances and prospects. Virology 454–455:340–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barouch DH, Deeks SG. 2014. Immunologic strategies for HIV-1 remission and eradication. Science 345:169–174. doi: 10.1126/science.1255512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Archin NM, Margolis DM. 2014. Emerging strategies to deplete the HIV reservoir. Curr Opin Infect Dis 27:29–35. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blankson JN, Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF. 2014. Finding a cure for human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am 28:633–650. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Besson GJ, Lalama CM, Bosch RJ, Gandhi RT, Bedison MA, Aga E, Riddler SA, McMahon DK, Hong F, Mellors JW. 2014. HIV-1 DNA decay dynamics in blood during more than a decade of suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 59:1312–1321. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasternak AO, Jurriaans S, Bakker M, Prins JM, Berkhout B, Lukashov VV. 2009. Cellular levels of HIV unspliced RNA from patients on combination antiretroviral therapy with undetectable plasma viremia predict the therapy outcome. PLoS One 4:e8490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eriksson S, Graf EH, Dahl V, Strain MC, Yukl SA, Lysenko ES, Bosch RJ, Lai J, Chioma S, Emad F, Abdel-Mohsen M, Hoh R, Hecht F, Hunt P, Somsouk M, Wong J, Johnston R, Siliciano RF, Richman DD, O'Doherty U, Palmer S, Deeks SG, Siliciano JD. 2013. Comparative analysis of measures of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 eradication studies. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003174. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams JP, Hurst J, Stöhr W, Robinson N, Brown H, Fisher M, Kinloch S, Cooper D, Schechter M, Tambussi G, Fidler S, Carrington M, Babiker A, Weber J, Koelsch KK, Kelleher AD, Phillips RE, Frater J. 2014. HIV-1 DNA predicts disease progression and post-treatment virological control. eLife 3:e03821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li JZ, Etemad B, Ahmed H, Aga E, Bosch RJ, Mellors JW, Kuritzkes DR, Lederman MM, Para M, Gandhi RT. 2016. The size of the expressed HIV reservoir predicts timing of viral rebound after treatment interruption. AIDS 30:343–353. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Doherty U, Swiggard WJ, Jeyakumar D, McGain D, Malim MH. 2002. A sensitive, quantitative assay for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integration. J Virol 76:10942–10950. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10942-10950.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malnati MS, Scarlatti G, Gatto F, Salvatori F, Cassina G, Rutigliano T, Volpi R, Lusso P. 2008. A universal real-time PCR assay for the quantification of group-M HIV-1 proviral load. Nat Protoc 3:1240–1248. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koelsch KK, Boesecke C, McBride K, Gelgor L, Fahey P, Natarajan V, Baker D, Bloch M, Murray JM, Zaunders J, Emery S, Cooper DA, Kelleher AD. 2011. Impact of treatment with raltegravir during primary or chronic HIV infection on RNA decay characteristics and the HIV viral reservoir. AIDS 25:2069–2078. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834b9658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasternak AO, Adema KW, Bakker M, Jurriaans S, Berkhout B, Cornelissen M, Lukashov VV. 2008. Highly sensitive methods based on seminested real-time reverse transcription-PCR for quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 unspliced and multiply spliced RNA and proviral DNA. J Clin Microbiol 46:2206–2211. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00055-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bullen CK, Laird GM, Durand CM, Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF. 2014. New ex vivo approaches distinguish effective and ineffective single agents for reversing HIV-1 latency in vivo. Nat Med 20:425–429. doi: 10.1038/nm.3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cillo AR, Vagratian D, Bedison MA, Anderson EM, Kearney MF, Fyne E, Koontz D, Coffin JM, Piatak M, Mellors JW. 2014. Improved single-copy assays for quantification of persistent HIV-1 viremia in patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol 52:3944–3951. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02060-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cillo AR, Sobolewski MD, Bosch RJ, Fyne E, Piatak M, Coffin JM, Mellors JW. 2014. Quantification of HIV-1 latency reversal in resting CD4+ T cells from patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:7078–7083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402873111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ledderose C, Heyn J, Limbeck E, Kreth S. 2011. Selection of reliable reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in human T cells and neutrophils. BMC Res Notes 4:427. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ocwieja KE, Sherrill-Mix S, Mukherjee R, Custers-Allen R, David P, Brown M, Wang S, Link DR, Olson J, Travers K, Schadt E, Bushman FD. 2012. Dynamic regulation of HIV-1 mRNA populations analyzed by single-molecule enrichment and long-read sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 40:10345–10355. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moir S, Donoghue ET, Pickeral OK, Malaspina A, Planta MA, Chun T-W, Krishnan SR, Kottilil S, Birse CE, Leitman SF, Fauci AS. 2003. Continuous flow leukapheresis induces expression of stress genes in lymphocytes: impact on microarray analyses. Blood 102:3852–3853. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strain MC, Lada SM, Luong T, Rought SE, Gianella S, Terry VH, Spina CA, Woelk CH, Richman DD. 2013. Highly precise measurement of HIV DNA by droplet digital PCR. PLoS One 8:e55943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiselinova M, Pasternak AO, De Spiegelaere W, Vogelaers D, Berkhout B, Vandekerckhove L. 2014. Comparison of droplet digital PCR and seminested real-time PCR for quantification of cell-associated HIV-1 RNA. PLoS One 9:e85999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Archin NM, Liberty AL, Kashuba AD, Choudhary SK, Kuruc JD, Crooks A, Parker MDC, Anderson EM, Kearney MF, Strain MC, Richman DD, Hudgens MG, Bosch RJ, Coffin JM, Eron JJ, Hazuda DJ, Margolis DM. 2012. Administration of vorinostat disrupts HIV-1 latency in patients on antiretroviral therapy. Nature 487:482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Søgaard OS, Graversen ME, Leth S, Olesen R, Brinkmann CR, Nissen SK, Kjaer AS, Schleimann MH, Denton PW, Hey-Cunningham WJ, Koelsch KK, Pantaleo G, Krogsgaard K, Sommerfelt M, Fromentin R, Chomont N, Rasmussen TA, Østergaard L, Tolstrup M. 2015. The depsipeptide romidepsin reverses HIV-1 latency in vivo. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005142. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasternak AO, DeMaster LK, Kootstra NA, Reiss P, O'Doherty U, Berkhout B. 2016. Minor contribution of chimeric host-HIV readthrough transcripts to the level of HIV cell-associated gag RNA. J Virol 90:1148–1151. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02597-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.