Abstract

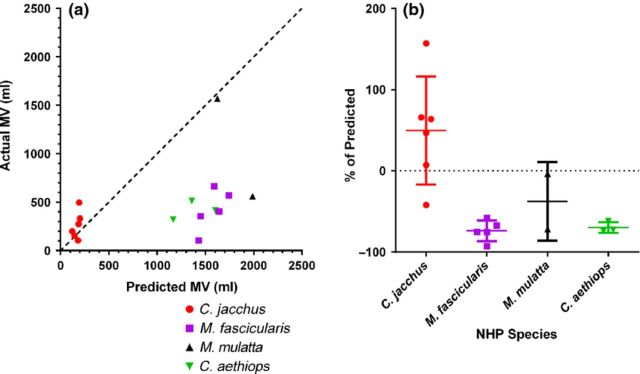

The aerosol characteristics of Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) were evaluated to achieve reproducible infection of experimental animals with aerosolized RVFV suitable for animal efficacy studies. Spray factor (SF), the ratio between the concentrations of the aerosolized agent to the agent in the aerosol generator, is used to compare performance differences between aerosol exposures. SF indicates the efficiency of the aerosolization process; a higher SF means a lower nebulizer concentration is needed to achieve a desired inhaled dose. Relative humidity levels as well as the duration of the exposure and choice of exposure chamber all impacted RVFV SF. Differences were also noted between actual and predicted minute volumes for different species of nonhuman primates. While NHP from Old World species (Macaca fascicularis, M. mulatta, Chlorocebus aethiops) generally had a lower actual minute volume than predicted, the actual minute volume for marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) was higher than predicted (150% for marmosets compared with an average of 35% for all other species examined). All of these factors (relative humidity, chamber, duration, and minute volume) impact the ability to reliably and reproducibly deliver a specific dose of aerosolized RVFV. The implications of these findings for future pivotal efficacy studies are discussed.

Keywords: aerosol, respiratory, infection

The aerosol characteristics of Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) were evaluated to achieve reproducible infection of experimental animals with aerosolized RVFV suitable for animal efficacy studies.

Graphical Abstract Figure.

The aerosol characteristics of Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) were evaluated to achieve reproducible infection of experimental animals with aerosolized RVFV suitable for animal efficacy studies.

Introduction

Rift Valley fever (RVF) is an endemic disease in sub Saharan Africa and the Middle East that periodically emerges to cause widespread disease in livestock and human populations (Gerdes, 2004; Ikegami, 2012). The causative agent is a segmented negative stranded RNA virus (RVFV) that can be transmitted via mosquito bite, contact with infected animals or carcasses, or inhalation (Shimshony & Barzilai, 1983; Turell & Rossi, 1991; Ross et al., 2012). In livestock, RVFV can cause significant mortality particularly among juvenile animals and is most notable for causing ‘abortion storms’ among ungulates (particularly sheep, goats and cattle). Most humans infected with RVFV develop an acute febrile disease and recover within 1–2 weeks. A subset of patients with RVF develops severe disease including retinitis, hepatitis, hemorrhagic fever, or encephalitis (Madani et al., 2003). Approximately 1–2% of humans infected with RVFV succumb to the infection.

Because RVFV can infect and cause disease via the respiratory tract, there is concern that it could be used as a biological weapon. Aerosol dissemination is thought to be the most likely route of a bioweapon attack whether carried out by terrorists or rogue nation states. RVFV has several properties considered ‘desirable’ in a bioweapon: it can be readily grown in tissue culture, the virus is relatively stable when aerosolized, and the infectious dose via the aerosol route is likely fairly low (Miller et al., 1963). Because RVFV remains stable in the environment, lying dormant in mosquito larvae for decades, and because it causes considerable mortality in livestock, there is additional concern that if RVFV was used as a weapon that it would become endemic in the United States in a manner similar to West Nile virus.

While clinical trials of medical countermeasures against RVF might be feasible if resources could be mobilized sufficiently quickly during an outbreak, it is very unlikely that there would be sufficient cases resulting from a verified aerosol exposure that could be used to license a medical countermeasure against an aerosol exposure. Licensure against aerosol exposure will only be possible using the FDA’s Animal Rule. In the FDA’s Guidance to Industry regarding the implementation of the Animal Rule, the FDA has indicated that for pivotal efficacy studies the route of exposure must be the same as the anticipated human exposure route (FDA, 2009, http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm078923.pdf). Further, the FDA requires that reliable quantification and reproducibility of the challenge dose be demonstrated. To achieve that for aerosol exposure, detailed characterization of aerosols containing the pathogenic agent is required. The effect of a number of potential variables on the dose must be evaluated including environmental conditions (relative humidity, temperature, chamber size) and the exposure duration. As part of an effort to develop animal models of aerosol exposure to RVFV (Bales et al., 2012) suitable for use in pivotal efficacy studies, this study addresses the effect of environmental conditions on the aerosolization of RVFV in our system.

Materials and methods

Biosafety and regulatory information

All work with live RVFV was conducted at biosafety level (BSL) 3 in the University of Pittsburgh Regional Biocontainment Laboratory (RBL). For respiratory protection, all personnel wore powered air purifying respirators (3M GVP 1 PAPR with l series bumpcap) or used a class III biological safety cabinet. All Nonhuman primates (NHPs) were housed in individual containment cages (Primate Products, Inc., Miami, FL). Vesphene II se (1 : 128 dilution, Steris Corporation, Erie, PA) was used to disinfect all liquid wastes and surfaces associated with the agent. All solid wastes, used caging, and animal wastes, were steam sterilized. Animal carcasses were digested via alkaline hydrolysis (Peerless Waste Solutions, Holland, MI). The University of Pittsburgh Regional Biocontainment Laboratory is a registered entity with the CDC/USDA for work with RVF.

NHPs

Healthy, adult common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus), cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis), rhesus macaques (M. mulatta) and African green monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops) of both sexes were purchased and housed in the RBL at ABSL 3 for these studies. Research was conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals. All research described herein adhered to the principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The facility where this research was conducted is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (Rockville, MD).

Virus

Recombinant RVFV strain ZH501 was kindly provided by Barry Miller (CDC, Ft. Collins, CO) and Stuart Nichol (CDC, Atlanta). Prior to receipt, the virus was generated from reverse genetics plasmids containing the wild type ZH501 sequence, which was confirmed by sequencing. Virus was propagated on Vero E6 cells using standard methods. For virus quantitation, plaque assays were performed using standard methods.

Aerosol exposures

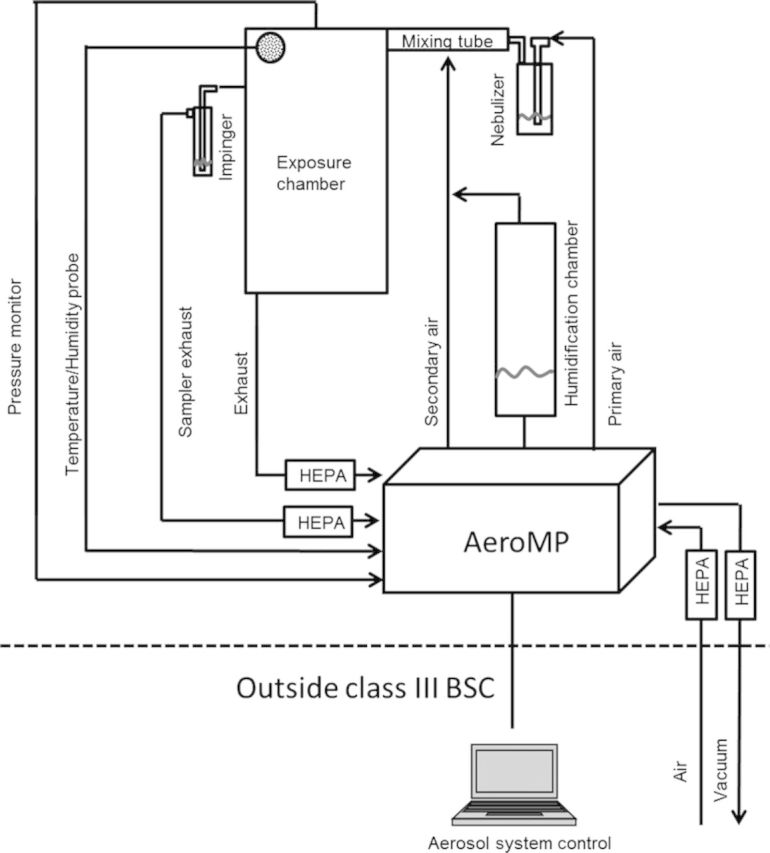

Aerosol exposures were conducted inside a class III biological safety cabinet. Figure 1a shows a schematic layout of the aerosol exposure system, while Table 1 lists the volumes and flow rates used for the different inhalation chambers. Aerosols were created by a 3 jet Collison nebulizer (BGI, Inc. Waltham, MA) run at 7.5 lpm and 28–30 psi controlled by the AeroMP exposure system (Biaera Technologies). Additional (secondary) air was added to the primary air flow to increase total air flow into the chamber at half of the chamber volume. A humidification chamber was used to raise relative humidity inside the inhalation chamber when needed. Aerosol samples were collected in an all glass impinger (AGI; Ace Glass, Vineland, NJ) operating at 6 lpm to determine the presented dose as previously described (Roy & Pitt, 2005). Aerosol and nebulizer samples were titrated by plaque assay to determine virus concentration. Total exhaust was set at the opposite rate of incoming air to insure a dynamic chamber with one air change inside the chamber every 2 min. Aerosol concentration is the product of the concentration of the pathogen in the AGI, and the volume of the AGI divided by the product of the duration of the exposure and the flow rate of the AGI. Spray factor (SF), which measures aerosol system performance, is the ratio of the aerosol concentration to the nebulizer concentration. Presented dose is calculated as the product of the aerosol concentration, the minute volume of the animal and the duration of the exposure. Figure 2a–c shows exposure chambers used in these studies.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of aerosol system. The figure shows a schematic representation of the aerosol system used in these studies to indicate placement of nebulizer, aerosol sampler, and other elements of the aerosol system.

Table 1.

Aerosol system parameters

| Chamber | Volume | Nebulizer air | Secondary air | Total air | Sampler vacuum | Exhaust vacuum | Total vacuum |

| RWB | 38.0 | 7.5 | 12.0 | 19.5 | 6.0 | 13.5 | 19.5 |

| MHO | 16.0 | 7.5 | 0.5 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 8.0 |

| NHP | 32.0 | .5 | 8.5 | 16.0 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 16.0 |

RWB, rodent whole body, MHO, marmoset head only, NHP, nonhuman primate head only.

Volume in cubic liters.

Flow rates are in liters per minute.

Figure 2.

Photographs of NHP exposed to aerosols of RVFV. Photographs were taken of (a) an African green monkey and (b) a marmoset exposed to RVFV. The photograph in (c) shows the head out plethysmograph chamber used to measure minute volume in marmosets.

Plethysmography

Minute volume in marmosets was assessed using a head out plethysmography chamber and operated with buxco xa software (Buxco Research Systems, Wilmington, NC) (Fig. 2d). Marmosets were anesthetized with 20 mg kg−1 of ketamine injected immediately prior to being placed in the chamber to assess respiratory function for 3 min. Macaques and African green monkeys were anesthetized with tiletamine/zolazepam (6 mg kg−1) or ketamine (9 mg kg−1) prior to plethysmography. Plethysmograph was conducted immediately prior to aerosol exposure to RVFV. Results of the aerosol exposure to RVFV are submitted for publication elsewhere.

Results

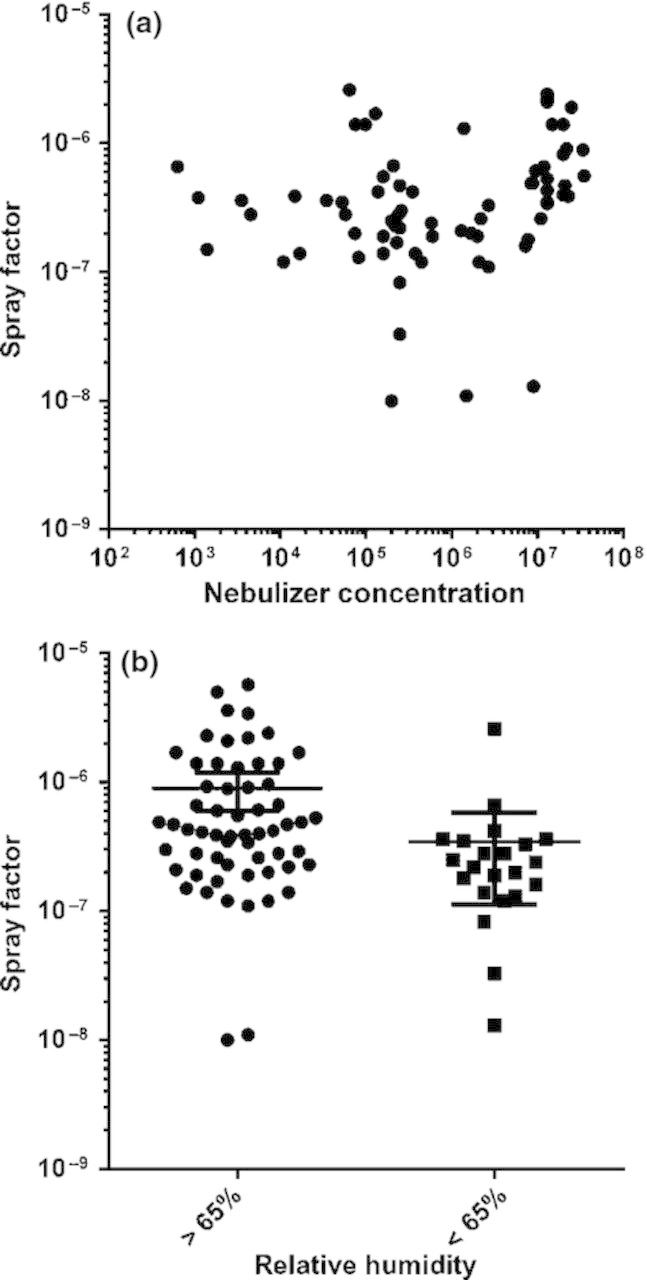

The goal of these studies was to evaluate parameters that could impact experimental aerosolization of RVFV into an exposure chamber in preparation for studies aimed at developing animal models of RVF and evaluating medical countermeasures in accordance with the FDA’s Animal Rule. In initial experiments, RVFV was aerosolized over a range of nebulizer concentrations into a rodent whole body (RWB) chamber to assess the ratio of the aerosol concentration to the nebulizer concentration (known as the SF)(Roy & Pitt, 2005). The SF is a unitless numerical value that quantifies the efficiency and performance of an aerosol (i.e. how much pathogen is lost during the aerosolization process). Over a 5 log10 PFU range of nebulizer concentrations, aerosol performance of RVFV as assessed by the SF was relatively stable with an average SF of 5.7 × 10−7 (95% confidence intervals: 4.2 × 10−7–7.14 × 10−7) and a coefficient of variation of 1.08 (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Aerosol performance of RVFV is affected by relative humidity but not nebulizer concentration. Aerosol performance of RVFV was assessed over a range of nebulizer concentrations and relative humidity using the RWB exposure chamber. Aerosol samples were collected and compared with nebulizer contents to determine SF. Graphs show dot plots of (a) nebulizer concentration (x axis) and SF (y axis), while (b) shows SF at ‘low’ (< 65%) and ‘high’ (≥ 65%) relative humidity over a range of virus concentrations. Filled circles in (a) and (b) are individual aerosol exposures, while the lines in (b) indicate the mean with 95% confidence limits indicated by error bars.

Because humidity has been shown to effect aerosolization of pathogens (Hood, 1961; Schaffer et al., 1976; Marthi et al., 1990; Walter et al., 1990; Roy et al., 2010; Faith et al., 2012), the impact of relative humidity inside the exposure chamber on the SF of RVFV was evaluated (Fig. 3b). Aerosols with a relative humidity of ≥ 65% had a higher SF (average 4.2 × 10−7) than aerosols with a relative humidity < 65% (average 2.3 × 10−7); this difference was significant by a two tailed t test (P = 0.0335). Therefore, higher humidity resulted in less loss of infectious virus during the aerosolization process. Based on this result, all subsequent aerosol experiments were conducted with the relative humidity set at 80%.

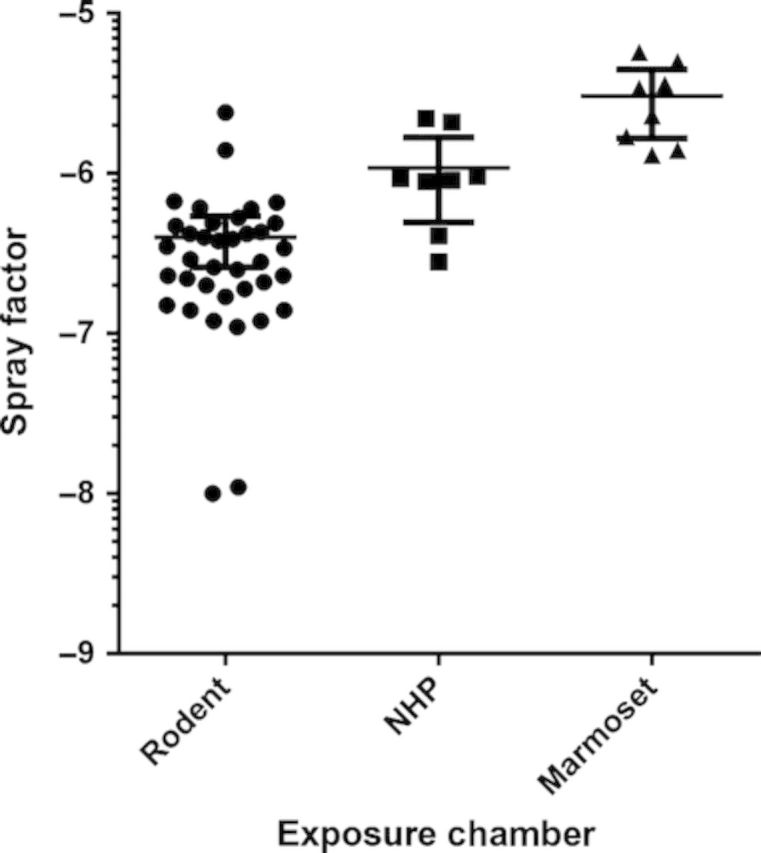

Depending upon the species of animal to be exposed and the desired exposure method (whole body compared with nose only), different aerosol exposure chambers might be employed which could impact SF. As shown in Fig. 4, SF was impacted by the choice of chamber, with the marmoset chamber having the best SF (average of 3.05 × 10−6), while the RWB exposure chamber had the worst, almost 10 fold lower than the marmoset chamber (average of 3.99 × 10−7). The NHP head out exposure chamber had a SF (average of 1.09 × 10−6) which was better than the rodent exposure chamber but not as good as the marmoset chamber. By one way anova, the marmoset chamber SF was statistically significantly different from the SF for the other chambers.

Figure 4.

Choice of exposure chamber impacts RVFV aerosolization. RVFV was aerosolized in RWB, NHP head only, or marmoset nose only exposure chambers. Aerosol samples were collected and compared with nebulizer contents to determine SF. Graph shows the SF for individual aerosol exposures (filled circles) as well as mean (line) and 95% confidence limits (error bars) for each exposure chamber.

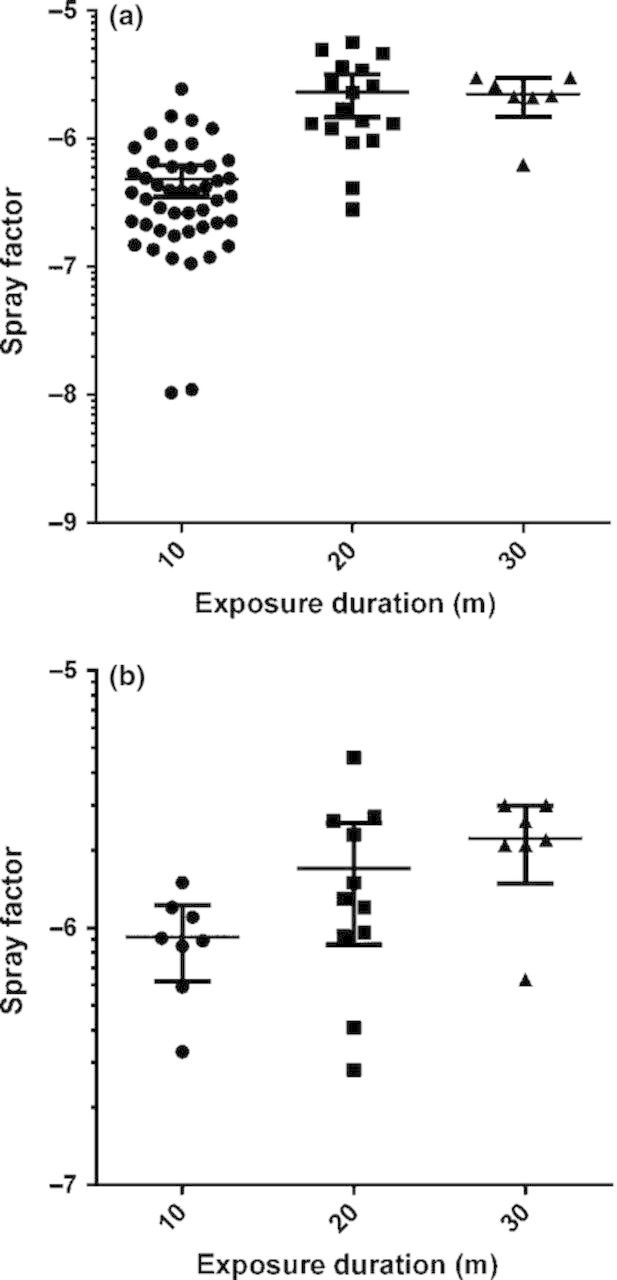

The impact of the duration of exposure on SF was also evaluated (Fig. 5a). The SF obtained with 20 and 30 min aerosols (average 2.31 × 10−6 and 2.23 × 10−6, respectively) was significantly better than that obtained with 10 min aerosols (average 4.86 × 10−7) by one way anova. When evaluating duration of exposure in the NHP head only chamber alone (Fig. 5b), the SF at 20 and 30 min (1.71 × 10−6 and 2.23 × 10−6, respectively) was better than the SF at 10 min (9.2 × 10−7) although the differences were only significant for the SF at 30 min using Tukey’s test with a one way anova (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Impact of exposure duration on RVFV aerosolization. RVFV was aerosolized for 10, 20, or 30 min, and aerosol samples were collected to determine the SF. Graphs show SF for individual aerosol exposures (filled circles) as well as the mean (line) and 95% confidence limits (error bars) after 10, 20, and 30 min for (a) all exposure chambers or restricted to the (b) NHP head out exposure chamber.

An additional variable that can affect the ability to deliver a desired target dose is the respiratory capacity of the animal species under study. For rodents, minute volume (the volume of air taken into the lungs in 1 min) is typically estimated using Guyton’s formula which assumes a linear relationship between the weight of the animal and minute volume. The minute volume of larger animals such as rabbits and NHPs is measured directly using a plethysmograph, typically either immediately before or during the exposure. NHPs are anesthetized during both the plethysmograph and the aerosol, which can suppress respiratory function including minute volume (Lopez et al., 2002; Iizuka et al., 2010). In agreement with this, cynomolgus macaques, rhesus macaques and African green monkeys had suppressed minute volumes compared with what was predicted by Guyton’s formula (Fig. 6). Unlike the Old World species, marmosets had a higher than predicted minute volume.

Figure 6.

Plethysmography data from NHPs. Minute volumes were measured for NHPs from cynomolgus macaques (purple squares), rhesus macaques (black triangles), African green monkeys (green triangles), and common marmosets (red circles). Graph in (a) shows actual minute volumes for individual animals of each species compared with predicted values based on Guyton’s formula. Graph in (b) shows % change in actual minute volume relative to the predicted value from Guyton’s formula.

Discussion

Prior data with a bacterial pathogen, Francisella tularensis, demonstrated that environmental factors, particularly relative humidity, can influence the aerosol concentration of the pathogen in an experimental setting (Cox & Goldberg, 1972; Faith et al., 2012). Changes in aerosol concentration impact the dose of the pathogen that can be delivered to an animal. The data reported here demonstrate that relative humidity levels above 65% improved the aerosolization process of RVFV as measured by SF. Previous studies with F. tularensis also found differences in SF between rodent nose only and whole body exposure chambers. For F. tularensis, the difference in exposure chambers was explained by disparities in relative humidity levels achieved in the two chambers without supplemental humidification. The finding that different exposure chambers had significantly different SFs for RVFV was unexpected, as supplemental humidification had been used to insure average relative humidity levels were > 65% for each exposure. The reason for the different SF based on exposure chamber is not clear. The difference in chamber volume between the RWB chamber (39 L) compared with the NHP chamber (33 L) does not seem sufficient to explain the nearly 1 log difference in SF.

Previously published data on plethysmography in marmosets suggested that similar to what has been seen in Old World NHP minute volume as measured by plethysmograph was suppressed relative to what would be predicted by Guyton’s formula as a result of anesthesia (Lever et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2009). This stands in clear contrast to the data presented here of higher than predicted minute volumes in marmosets. In our studies, marmosets were anesthetized with 20 mg kg−1 ketamine, while in the prior reports, marmosets were anesthetized with 25 mg kg−1. While it seems unlikely that the difference in ketamine dose could account for the entire difference in minute volumes reported, it is possible. Marmosets are relatively resistant to the effects of ketamine compared with other NHP species, requiring considerably higher doses to achieve the same level of restraint. Additional explanations for the discrepancies include the source and the age of the marmosets as well as the type of chamber used to measure minute volume and the duration of the plethysmograph. These data do illustrate that projections based on historical data could be unreliable, and minute volume should be measured directly rather than estimated whenever possible.

The objective of these studies was to characterize aerosols containing RVFV in order to establish the parameters needed to satisfy FDA requirements for pivotal efficacy studies in animals to evaluate medical countermeasures against RVFV. It is desirable to use as little RVFV as necessary to achieve the desired dose to insure use of the same stock for all studies as this will eliminate potential concerns regarding variations in virus stocks. Determination of the aerosol SF for a pathogen allows determination of the nebulizer concentration required to achieve a desired target dose. The results of such calculations are shown in Table 2 using the median SFs obtained for each chamber evaluated in these studies. Using the marmoset nose only chamber allows for a full log10 lower concentration of RVFV in the nebulizer to achieve the same dose than would be required for an exposure in a RWB chamber, assuming equivalent exposure duration and minute volume. Further study is needed to understand the different SF between exposure chambers and the effects of R.H. on SF. The data presented here will be useful in future studies to evaluate medical countermeasures against RVFV.

Table 2.

Nebulizer concentration required to achieve target dose of 1000 PFU in different exposure chambers

| Chamber | Weight (kg) | MV (L min−1) | Target dose (PFU) | Exposure time (min) | Respired volume (L) | Aerosol conc. (PFU L−1) | Spray factor | Nebulizer conc. (PFU mL−1) |

| Rodent whole body | 5 | 1.25 | 1000 | 10 | 1.25 × 104 | 8.0 × 101 | 2.9 × 10−7 | 2.8 × 105 |

| NHP head only | 5 | 1.25 | 1000 | 10 | 1.25 × 104 | 8.0 × 101 | 9.2 × 10−7 | 8.7 × 104 |

| Marmoset nose only | 5 | 1.25 | 1000 | 10 | 1.25 × 104 | 8.0 × 101 | 2.9 × 10−6 | 2.8 × 104 |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Defense Joint Project Manager Medical Countermeasure Systems JPM MCS program through the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) contract HDTRA1 10 C 1066. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or official position of JPM MCS. JPM MCS, a component of the Joint Program Executive Office for Chemical and Biological Defense, aims to provide U.S. military forces and the nation with safe, effective, and innovative medical solutions to counter chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats. JPM MCS facilitates the advanced development and acquisition of medical countermeasures and systems to enhance our nation’s biodefense response capability. For more information, visit www.jpeocbd.osd.mil. We would like to thank the Division of Laboratory Animal Resource’s veterinary technicians who work in the University of Pittsburgh’s Regional Biocontainment Laboratory and assisted with these studies.

Footnotes

Methods for aerosolization are important considerations for effective experimental strategies for any BSL3 pathogen. This study provides an excellent example of how aerosolization methods can impact study results.

Editor: Gerald Byrne

References

- Bales JM, Powell DS, Bethel LM, Reed DS, Hartman AL. (2012) Choice of inbred rat strain impacts lethality and disease course after respiratory infection with Rift Valley Fever Virus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2: 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CS, Goldberg LJ. (1972) Aerosol survival of Pasteurella tularensis and the influence of relative humidity. Appl Microbiol 23: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith SA, Smith LP, Swatland AS, Reed DS. (2012) Growth conditions and environmental factors impact aerosolization but not virulence of Francisella tularensis infection in mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2: 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes GH. (2004) Rift Valley fever. Rev Sci Tech 23: 613–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood AM. (1961) Infectivity of Pasteurella tularensis clouds. J Hyg (Lond) 59: 497–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka H, Sasaki K, Odagiri N, Obo M, Imaizumi M, Atai H. (2010) Measurement of respiratory function using whole body plethysmography in unanesthetized and unrestrained nonhuman primates. J Toxicol Sci 35: 863–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami T. (2012) Molecular biology and genetic diversity of Rift Valley fever virus. Antiviral Res 95: 293–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever MS, Stagg AJ, Nelson M, Pearce P, Stevens DJ, Scott EA, Simpson AJ, Fulop MJ. (2008) Experimental respiratory anthrax infection in the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). Int J Exp Pathol 89: 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez KR, Gibbs PH, Reed DS. (2002) A comparison of body temperature changes due to the administration of ketamine acepromazine and tiletamine zolazepam anesthetics in cynomolgus macaques. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 41: 47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madani TA, Al Mazrou YY, et al. (2003) Rift Valley fever epidemic in Saudi Arabia: epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics. Clin Infect Dis 37: 1084–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marthi B, Fieland VP, Walter M, Seidler RJ. (1990) Survival of bacteria during aerosolization. Appl Environ Microbiol 56: 3463–3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WS, Demchak P, Rosenberger CR, Dominik JW, Bradshaw JL. (1963) Stability and infectivity of airborne Yellow Fever and Rift Valley Fever viruses. Am J Hyg 77: 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M, Lever MS, Savage VL, Salguero FJ, Pearce PC, Stevens DJ, Simpson AJ. (2009) Establishment of lethal inhalational infection with Francisella tularensis (tularaemia) in the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). Int J Exp Pathol 90: 109–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross TM, Bhardwaj N, Bissel SJ, Hartman AL, Smith DR. (2012) Animal models of Rift Valley fever virus infection. Virus Res 163: 417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy CJ, Pitt LM. (2005) Infectious disease aerobiology: aerosol challenge methods. Biodefense: Research Methodology and Animal Models. (Swearengen JR, Ed), pp. 61–76. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Roy CJ, Reed DS, Hutt JA. (2010) Aerobiology and inhalation exposure to biological select agents and toxins. Vet Pathol 47: 779–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer FL, Soergel ME, et al. (1976) Survival of airborne influenza virus: effects of propagating host, relative humidity, and composition of spray fluids. Arch Virol 51: 263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimshony A, Barzilai R. (1983) Rift Valley fever. Adv Vet Sci Comp Med 27: 347–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turell MJ, Rossi CA. (1991) Potential for mosquito transmission of attenuated strains of Rift Valley fever virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg 44: 278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter MV, Marthi B, Fieland VP, Ganio LM. (1990) Effect of aerosolization on subsequent bacterial survival. Appl Environ Microbiol 56: 3468–3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]