Abstract

Deprivation indices have been widely used to evaluate neighborhood socioeconomic status and therefore examine individuals within their regional context. Although some studies on the development of deprivation indices were conducted in Korea, additional research is needed to construct a more valid and reliable deprivation index. Therefore, a new deprivation index, named the K index, was constructed using principal component analysis. This index was compared with the Carstairs, Townsend and Choi indices. A possible association between infant death and deprivation was explored using the K index. The K index had a higher correlation with the infant mortality rate than did the other three indices. The regional deprivation quintiles were unequally distributed throughout the country. Despite the overall trend of gradually decreasing infant mortality rates, inequalities in infant deaths according to the deprivation quintiles persisted and widened. Despite its significance, the regional deprivation variable had a smaller effect on infant deaths than did individual variables. The K index functions as a deprivation index, and we may use this index to estimate the regional socioeconomic status in Korea. We found that inequalities in infant deaths according to the time trend persisted. To reduce the health inequalities among infants in Korea, regional deprivation should be considered.

Keywords: Social Class, Infant Death, Reliability and Validity

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The deprivation index is one of the methods used to estimate the socioeconomic status of an area, and it is inversely related to infant mortality (1,2). Although the overall infant mortality rate has gradually decreased, inequalities in infant deaths persist (3,4,5). In particular, several articles demonstrated that the regional deprivation index is associated with the infant mortality rate. Singh et al. (6) demonstrated that the interquintile differences in infant mortality rate increased from 1969 to 2000 in the United States.

Many early studies on the deprivation index focused on two deprivation indices. The first index was developed by Carstairs and Morris (7), and the second index was created by Townsend (8) in the UK Carstairs and Morris constructed a deprivation index based on male unemployment, overcrowding, lack of a car and low social class by averaging each normalized z score with the same weight (7). Townsend used a similar approach but replaced the low social class variable with a homeownership variable (8). Subsequently, other methods that used the statistical analysis tool of principal component analysis (PCA) were developed in different countries, namely, New Zealand (9), Italy (10), the USA (11), and France (12). Pampalon and Raymond (13) conducted PCA using 6 socioeconomic indicators and reduced these indicators to 2 factors. The first and second factors were represented as material and social components, respectively.

In Korea, a few studies were conducted using either the Carstairs method (14,15,16,17) or the PCA method. Choi et al. (18) constructed a deprivation index by summing the z scores of 11 socioeconomic variables. However, we constructed a deprivation index by weighting each variable’s loadings (component score coefficients) resulting from PCA.

Studies constructing a deprivation index by using PCA have recently been conducted in Korea. Therefore, additional research is needed to construct a more valid and reliable deprivation index. In addition, determining a possible association between deprivation (in regards to the neighborhood’s material insufficiency and social position) and infant death is crucial to estimating infants’ health status. Therefore, the current study is quite timely.

The objectives of our study were as follows. First, we constructed a new index based on the Korean context using PCA. Second, we evaluated the validity and reliability of the new deprivation index. Third, we investigated the relationship between deprivation and infant deaths.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

To analyze infant deaths, retrospective birth cohort data were used. The cohort data consisted of all infants born from 1995 to 2008 in Korea (7,810,689 cases). The data included birth record variables (sex, gestational age, baby weight, birth date, birth place, parental age, parental education and parental occupation) and death record variables (death date, age at death and cause of death). The birth cohort was constructed by linking the birth and death registration record data sets using the individual identification numbers. Cases with missing values on the parental education and occupation variables were deleted (25,885 cases; 0.33%). Finally, there were 7,784,804 births cases and 7,569,378.5 person-years. There were 14,772 infant deaths. The birth cohort data were obtained from the Korean National Statistics Office.

Variables

Using the birth cohort data, we categorized the parents’ ages into the following ranges: < 20, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, 35-39 and ≥ 40 years. The parents’ education was grouped into the following categories: ≥ university (≥ 13 years), high school (10-12 years) and ≤ middle school (≤ 9 years). Parents’ occupation was classified into non-manual occupation (legislators and managers, professionals, and technicians and clerks), manual occupation (service and sales workers, agricultural workers, crafts, machine operators and assemblers, and laborers) and economically inactive status (students and housewives). Gestational age was categorized into the following ranges: < 36, 36-37, 37-38, 38-39, 39-40, 40-41, 41-42 and ≥ 42 weeks. The infants’ birthweight was grouped into the following categories: < 2,000, 2,000-2,500, 2,500-3,000, 3,000-3,500, 3,500-4,000 and ≥ 4,000 grams.

The composition of the regional variable in the 1995-2008 birth cohort data and the 2000 population census data differed. In Korea, administrative regions were re-numbered, subdivided into smaller regions or grouped into larger regions from 1995 to 2008. The regional variable included 282 regions in the birth cohort data and 246 in the census data. Due to the differing compositions of the regional variable, the variable was rearranged into the following 242 regions: Seoul (25 regions), Busan (16 regions), Daegu (8 regions), Incheon (10 regions), Gwangju (5 regions), Daejeon (5 regions), Ulsan (4 regions), Gyeonggi (38 regions), Gangwon (18 regions), North Chungcheong (13 regions), South Chungcheong (15 regions), North Jeolla (15 regions), South Jeolla (22 regions), North Gyeongsang (24 regions), South Gyeongsang (20 regions) and Jeju (4 regions).

Constructing the deprivation index

To construct the deprivation index, we used 10% of the 2000 population census data. The census data (4,845,543 cases) were constructed by linking population (4,845,543 cases) and housing and household data (1,433,342 cases) using household identification numbers. The total population was estimated by using weighting variables for 10% of the population data. The census data included population variables (age, sex, education, occupation and relationship between households), social variables (employment status and marriage), and housing and household variables (type of household, number of persons in a household, number of rooms, number of cars and housing area). The census data were obtained from the Korean National Statistics Office.

We conducted PCA by varimax rotation using 8 socioeconomic indicators (male unemployment, low social class, overcrowding, lack of a car, marriage, single-parent family, elderly people and low level of education) from the 2000 population census data. Four of these variables (male unemployment, low social class, overcrowding and lack of a car) were used in the Carstairs index. The other four variables (marriage, single-parent family, elderly people and low level of education) are important indicators for evaluating regional deprivation in the context of Korea. The proportion of elderly people increases according to the population pyramid (19). Although family and marriage have important meaning in Korea, the divorce rate and proportion of single-parent families have increased (20). Parents are dedicated to their children’s education (education fever), and private education costs are high in Korea (21). Therefore, these variables are important in the context of Korea. We also considered variables that are commonly used in articles that construct a deprivation index (10,22). The eight variables were normalized into z scores with a mean of 0 and variance of 1. The new index, which was constructed using PCA, was named the K index. The PCA method used in the current study followed an approach that is similar to that employed in an article by Pampalon et al. (22), in which PCA was performed using 6 socioeconomic indicators, which were reduced to two factors. The two factors corresponded to material and social components. We conducted PCA by modifying the socioeconomic indicators to match the Korean context and using variables that are common worldwide. As the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value approaches one, more of the total variance is explained by the factors and sampling becomes more adequate. Bartlett's test of sphericity evaluates the variables’ correlations with each other. If the null hypothesis is rejected, the variables are strongly correlated and the sampling is adequate.

We categorized the K index into five quintiles (Q1, 0%-20%; Q2, 20%-40%; Q3, 40%-60%; Q4, 60%-80%; Q5, 80%-100%) by weighting the population. The effect of deprivation was estimated by comparing the five quintiles. The Carstairs and Townsend indices were constructed by averaging the four normalized z scores. The deprivation index developed by Choi et al. (18) was constructed by summing the z scores of 10 socioeconomic variables rather than the original 11 variables because one variable (Poor housing environment) is described too vaguely to be calculated. We call this index the Choi index.

Data analysis estimating the association between deprivation and infant death

We applied deprivation indices that were constructed from a 2000 population census to the 1995-2008 birth cohort data using a regional variable. Scatter plots correlating the K, Carstairs, Townsend and Choi indices with the infant mortality rate were graphed. Using Pearson’s correlation analysis, we correlated these indices with the infant mortality rate to confirm the validity. Reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha values, which represent internal consistency.

We calculated the infant mortality rate, incidence density and univariable hazard ratios according to several sociodemographic variables. To determine the distribution of the quintiles, a 100% population cumulative graph of the major cities and provinces was created. To determine the trend for inequalities in infant deaths, the infant mortality rate and hazard ratios were graphed in 2-year intervals from 1995 to 2008 according to the deprivation quintiles.

For the survival analysis, the birth cohort data were utilized as follows. The start of the cohort study was January 1, 1995, and the end was December 31, 2008. The events in the survival analysis were defined as infant deaths, which were deaths before 356 days from the infants’ births (< 356 days). Infant deaths occurring after 365 days were not counted as events. Survival time was calculated as the time from the birth date to the death date or the termination of the study (before 356 days from birth). The survival time of the babies living longer than 365 days was 1 year.

To determine the effects of individual- and regional-level variables, a survival analysis (frailty model) for infant deaths was conducted. Model 1 was the default model with regional random effects. Model 2 also included the sex, gestational age and birth weight variables. Model 3 included the sex, gestational age, birth weight, parental education and parental occupation variables. Model 4 included the sex, gestational age, birth weight, parental education, parental occupation and K index variables. A likelihood ratio test (LRT) of the models was conducted to select the best-fitting model. We conducted multilevel survival analysis following the method used in Juhn et al. (23).

To evaluate the interactive effects between deprivation quintiles (Q1 and Q5; the least and most deprived) and socioeconomic variables, such as parental education and occupation, we used the Cox proportional hazard model for survival analysis.

The PCA and scatter plots were conducted using SPSS (Ver. 21, IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Survival analysis, tabulation and calculations were conducted using SAS (ver. 9.4, SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The significance level was established as 0.05 throughout the study.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Kangwon National University (IRB No. KWNUIRB-2015-11-001). Informed consent was exempted by the board.

RESULTS

Constructing deprivation indices

The definitions of the socioeconomic variables and the results of PCA are shown in Table 1. Eight socioeconomic variables were reduced to two factors. Factor 1 was highly correlated with 6 variables (marriage, lack of car, single family, elderly people, low level of education, and low social class). Factor 2 was correlated with 2 variables (overcrowding and male unemployment). Factor 1 represented a social component, and factor 2 represented a material component. The eigenvalues of factors 1 and 2 were 5.138 and 1.726, respectively. Factor 1 explained 64.2% of the total variance, and factor 2 explained 21.6%. We defined the first factor as the K index, which explained the largest portion of the total variance. The PCA’s KMO value was 0.827. The result of a Bartlett's chi-square test was statistically significant (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1. The definitions of the socioeconomic variables and the results of PCA.

| Definition of socioeconomic variables | Socioeconomic variables | Factor 1* | Factor 2* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Divorced or bereaved people over the age of 15 yr / total people over the age of 15 yr | Marriage | 0.958 | 0.199 |

| Heads of households without a car / total heads of households | Lack of car | 0.948 | -0.014 |

| Single-person households / total households | Single family | 0.929 | -0.013 |

| People over 65 yr of age / total people | Old people | 0.929 | 0.294 |

| No education or less than elementary level of education in population over the age of 15 yr / total population over the age of 15 yr | Low level of education | 0.912 | 0.366 |

| Heads of households with manual occupation / total economically active heads of households | Low social class | 0.833 | 0.331 |

| Over 1.5 persons / room in ordinary households / total ordinary households | Overcrowding | 0.013 | 0.891 |

| Unemployed among the economically active men aged 15-64 yr / total economically active men aged 15-64 yr | Men's unemployment | -0.266 | -0.749 |

| Eigenvalue | 5.138 | 1.726 | |

| Explained variance | 64.229 | 21.574 | |

| Cumulative variance | 64.229 | 85.803 | |

| KMO† = 0.827, Bartlett's χ2 = 2,865.506 (P < 0.001) | |||

*Varimax rotation. †KMO, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

Validity and reliability

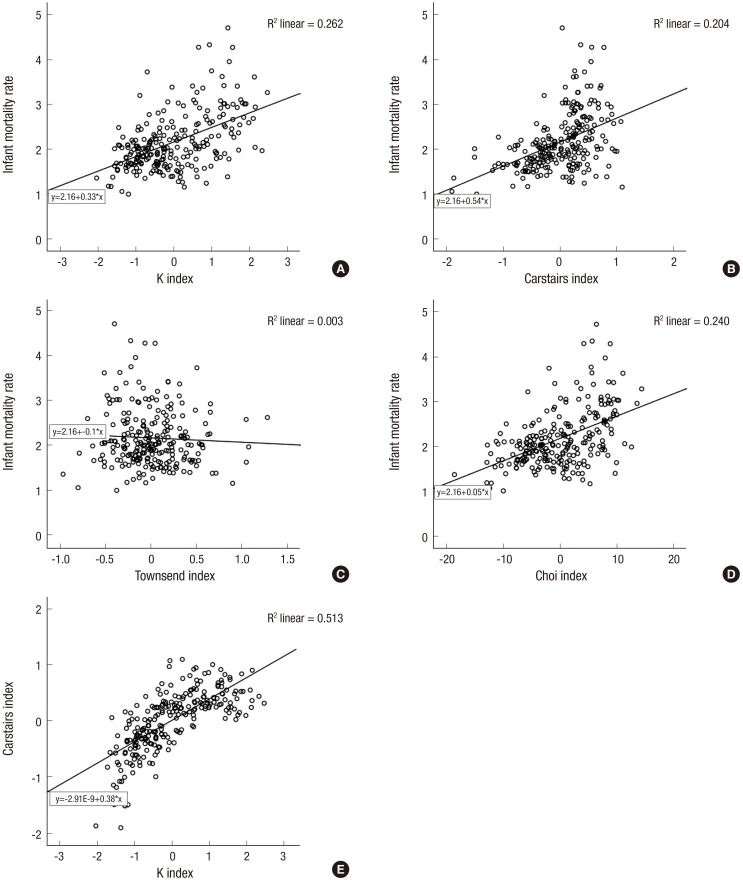

To confirm the validity of the deprivation indices, we created scatter plots correlating the K, Carstairs, Townsend and Choi indices with the infant mortality rate for the 242 regions, as shown in Fig. 1. The K, Carstairs and Choi indices were positively correlated with the infant mortality rate, but the Townsend index had a negative correlation. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the K index and infant mortality rate was 0.511 (95% CI: 0.418-0.600), while that for the Carstairs index and infant mortality rate was 0.451 (95% CI: 0.349-0.543). The correlation between the Townsend index and infant mortality rate was -0.052 (95% CI: -0.171-0.064), while that between the Choi index and infant mortality rate was 0.489 (95% CI: 0.399-0.578). The correlation between the K and Carstairs indices was 0.716 (95% CI: 0.671-0.762) (18). All correlation analyses were conducted on the data set including the 242 regions.

Fig. 1.

Scatter plots of the infant mortality rate, K index and Carstairs index for 242 regions.

(A) Scatter plot correlating the infant mortality rate and the K index. (B) Scatter plot correlating the infant mortality rate with the Carstairs index. (C) Scatter plot correlating the infant mortality rate with the Townsend index. (D) Scatter plot correlating the infant mortality rate with the Choi index. (E) Scatter plot correlating the Carstairs index with the K index.

Cronbach’s alphas of the K and Choi indices were 0.973 and 0.825, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha values for the Carstairs and Townsend indices were within the range considered unreliable (0.161 and -1.426, respectively). The K index displayed greater validity and reliability than the other indices (Fig. 1).

Table 2 presents the regional characteristics of the 16 major cities and provinces in Korea. Metropolitan areas, including Seoul and Gyeonggi, showed low percentages of old people and low levels of social class. The metropolitan areas displayed a negative excess infant mortality rate (-0.32 and -0.10 deaths per 1,000 births) and a negative average value on the K index (-0.591 and -0.946). The metropolitan regions were urban areas with expensive house prices, high costs of living and better regional accessibility to health and medical care. The population living in the metropolitan regions was younger and better able to afford medical expenditures than those in the local provinces. By contrast, North Jeolla, South Jeolla and North Gyeongsang showed high percentages of old people and low levels of social class. These local provinces displayed a positive excess infant mortality rate (0.40, 0.37 and 0.37) and positive average value on the K index (0.746, 1.045 and 0.704). The local provinces were areas with cheap house prices, low costs of living cost and poor regional accessibility to health and medical care. Agricultural workers and the old people tended to live in the local provinces rather than the metropolitan areas. Overall, the regions with a higher excess mortality rate showed a higher level of deprivation. The K index reflected the change in the excess infant mortality rate and can be used as an indicator of infant death. We claim that the K index has sociocultural meaning in Korea.

Table 2. Regional characteristics of the 16 major cities and provinces in Korea.

| Regional characteristics | 2010 census | 1995-2008 birth cohort | K index | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Old people, % | Low social class, % | Births | Infant deaths | IMR* | Excess IMR* | Mean (SD) | (Min, Max) | |

| Seoul | 978,185 | 5.5 | 51.9 | 1,636,868 | 2,590 | 1.58 | -0.32 | -0.591 (0.511) | (-1.609, 0.258) |

| Busan | 376,464 | 6.3 | 65.4 | 501,068 | 933 | 1.86 | -0.04 | -0.131 (0.552) | (-0.938, 0.982) |

| Daegu | 249,046 | 6.1 | 63.5 | 387,336 | 763 | 1.97 | 0.07 | -0.304 (0.662) | (-0.946, 0.683) |

| Incheon | 247,457 | 5.6 | 62.1 | 426,680 | 793 | 1.86 | -0.04 | -0.468 (0.946) | (-1.486, 1.237) |

| Gwangju | 143,836 | 5.7 | 59.0 | 245,664 | 456 | 1.86 | -0.04 | -0.707 (0.513) | (-1.141, 0.114) |

| Daejeon | 146,274 | 5.6 | 55.8 | 241,012 | 488 | 2.02 | 0.13 | -0.875 (0.485) | (-1.342, -0.170) |

| Ulsan | 105,407 | 4.1 | 65.6 | 157,930 | 345 | 2.18 | 0.29 | -1.080 (0.320) | (-1.454, -0.718) |

| Gyeonggi | 941,918 | 5.9 | 57.1 | 1,773,479 | 3,184 | 1.80 | -0.10 | -0.946 (0.514) | (-2.035, 0.119) |

| Gangwon | 167,947 | 10.1 | 73.2 | 225,858 | 508 | 2.25 | 0.35 | 0.130 (0.423) | (-0.494, 0.685) |

| N. Chungcheong | 164,759 | 9.9 | 70.1 | 237,217 | 510 | 2.15 | 0.25 | 0.089 (0.721) | (-0.977, 1.232) |

| S. Chungcheong | 209,435 | 12.3 | 75.0 | 295,801 | 585 | 1.98 | 0.08 | 0.237 (0.577) | (-0.992, 1.130) |

| N. Jeolla | 208,846 | 11.4 | 72.6 | 293,989 | 675 | 2.30 | 0.40 | 0.746 (0.994) | (-0.992, 1.868) |

| S. Jeolla | 215,013 | 13.8 | 78.5 | 303,031 | 687 | 2.27 | 0.37 | 1.045 (0.853) | (-1.068, 2.099) |

| N. Gyeongsang | 318,228 | 11.8 | 75.7 | 410,943 | 928 | 2.26 | 0.36 | 0.704 (0.954) | (-1.206, 2.151) |

| S. Gyeongsang | 318,771 | 9.2 | 69.8 | 548,404 | 1,152 | 2.10 | 0.20 | 0.688 (1.234) | (-1.424, 2.471) |

| Jeju | 53,957 | 8.5 | 72.5 | 99,524 | 175 | 1.76 | -0.14 | 0.067 (0.826) | (-0.904, 0.893) |

| Overall | 4,845,543 | 7.5 | 62.8 | 7,784,804 | 14,772 | 1.90 | 0.00 | 0.000 (1.000) | (-2.035, 2.471) |

*IMR, infant mortality rate (infant deaths per 1,000 births). SD, standard deviation; Min, minimum; Max, maximum.

Differences in infant mortality rate, incidence density and hazard ratio according to deprivation quintiles

The average infant mortality rate and incidence density were 1.90 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.87–1.93) per 1000 births and 19.52 (95% CI: 19.20–19.83) per 10,000 person-years, respectively. The univariable hazard ratio of the most deprived quintile (Q5; fifth quintile) of the K index was 1.261 (95% CI: 1.199–1.326). The infant mortality rate, incidence density and univariable hazard ratios increased for the most deprived quintiles (Q5), male babies, gestational age of < 36 weeks, birth weight of < 2,500 g, parents’ age < 20 years, parents’ education ≤ middle school, and parents’ manual occupation (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptions of the data according to deprivation quintiles.

| Sociodemographic variables | Total births | Person-yr | Infant deaths | IMR* (95% CI†) | ID‡ (95% CI§) | Univariable HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 7,784,804 | 7,569,378.5 | 14,772 | 1.90 (1.87-1.93) | 19.52 (19.20-19.83) | ||

| K index | Q1 | 1,586,735 | 1,540,704.5 | 2,726 | 1.72 (1.65-1.78) | 17.69 (17.03-18.36) | Ref. (1.000) |

| Q2 | 1,465,519 | 1,423,804.2 | 2,642 | 1.80 (1.73-1.87) | 18.56 (17.85-19.26) | 1.049 (0.994-1.107) | |

| Q3 | 1,622,118 | 1,576,332.6 | 3,116 | 1.92 (1.85-1.99) | 19.77 (19.07-20.46) | 1.118 (1.062-1.177) | |

| Q4 | 1,552,407 | 1,511,480.5 | 2,907 | 1.87 (1.80-1.94) | 19.23 (18.53-19.93) | 1.088 (1.033-1.146) | |

| Q5 | 1,558,025 | 1,517,056.8 | 3,381 | 2.17 (2.10-2.24) | 22.29 (21.54-23.04) | 1.261 (1.199-1.326) | |

| Sex | male | 4,063,437 | 3,952,138.5 | 8,116 | 2.00 (1.95-2.04) | 20.54 (20.09-20.98) | 1.116 (1.080-1.153) |

| female | 3,721,367 | 3,617,240.0 | 6,656 | 1.79 (1.75-1.83) | 18.40 (17.96-18.84) | Ref. (1.000) | |

| Gestational age | 0-36 | 172,803 | 164,534.4 | 3,100 | 17.94 (17.31-18.57) | 188.41 (181.78-195.04) | 15.789 (14.587-17.089) |

| 36-37 | 139,739 | 133,912.6 | 525 | 3.76 (3.44-4.08) | 39.20 (35.85-42.56) | 3.286 (2.941-3.673) | |

| 37-38 | 367,395 | 350,043.6 | 853 | 2.32 (2.17-2.48) | 24.37 (22.73-26.00) | 2.038 (1.848-2.247) | |

| 38-39 | 1,211,170 | 1,162,562.4 | 2,000 | 1.65 (1.58-1.72) | 17.20 (16.45-17.96) | 1.442 (1.327-1.567) | |

| 39-40 | 1,638,247 | 1,579,093.1 | 2,177 | 1.33 (1.27-1.38) | 13.79 (13.21-14.37) | 1.157 (1.066-1.257) | |

| 40-41 | 3,462,035 | 3,402,517.8 | 5,090 | 1.47 (1.43-1.51) | 14.96 (14.55-15.37) | 1.264 (1.171-1.364) | |

| 41-42 | 659,623 | 644,050.7 | 764 | 1.16 (1.08-1.24) | 11.86 (11.02-12.70) | Ref. (1.000) | |

| 42- | 120,171 | 119,189.6 | 224 | 1.86 (1.62-2.11) | 18.79 (16.33-21.25) | 1.592 (1.372-1.848) | |

| Birth weight | 0-2000 | 76,236 | 71,503.2 | 2,802 | 36.75 (35.39-38.12) | 391.87 (377.36-406.38) | 33.349 (31.566-35.234) |

| 2000-2500 | 220,291 | 212,095.7 | 1,223 | 5.55 (5.24-5.86) | 57.66 (54.43-60.89) | 4.928 (4.599-5.282) | |

| 2500-3000 | 1,417,515 | 1,373,307.8 | 3,099 | 2.19 (2.11-2.26) | 22.57 (21.77-23.36) | 1.932 (1.831-2.038) | |

| 3000-3500 | 3,609,562 | 3,509,094.6 | 4,821 | 1.34 (1.30-1.37) | 13.74 (13.35-14.13) | 1.177 (1.120-1.237) | |

| 3500-4000 | 2,045,977 | 1,996,447.3 | 2,327 | 1.14 (1.09-1.18) | 11.66 (11.18-12.13) | Ref. (1.000) | |

| 4000- | 409,358 | 401,178.9 | 468 | 1.14 (1.04-1.25) | 11.67 (10.61-12.72) | 1.002 (0.907-1.107) | |

| Father's age | < 20 | 12,489 | 12,224.8 | 55 | 4.40 (3.24-5.57) | 44.99 (33.10-56.88) | 2.529 (1.941-3.297) |

| 20-24 | 217,628 | 214,144.0 | 606 | 2.78 (2.56-3.01) | 28.30 (26.05-30.55) | 1.587 (1.460-1.725) | |

| 25-29 | 2,188,337 | 2,148,462.3 | 4,044 | 1.85 (1.79-1.90) | 18.82 (18.24-19.40) | 1.055 (1.014-1.098) | |

| 30-34 | 3,615,083 | 3,519,124.8 | 6,296 | 1.74 (1.70-1.78) | 17.89 (17.45-18.33) | Ref. (1.000) | |

| 35-39 | 1,400,653 | 1,341,907.9 | 2,780 | 1.98 (1.91-2.06) | 20.72 (19.95-21.49) | 1.152 (1.102-1.205) | |

| > 40 | 327,393 | 311,639.3 | 889 | 2.72 (2.54-2.89) | 28.53 (26.65-30.40) | 1.583 (1.476-1.698) | |

| Mother's age | < 20 | 56,216 | 55,039.9 | 248 | 4.41 (3.86-4.96) | 45.06 (39.45-50.67) | 2.524 (2.221-2.869) |

| 20-24 | 941,449 | 927,693.7 | 2,274 | 2.42 (2.32-2.51) | 24.51 (23.50-25.52) | 1.376 (1.308-1.448) | |

| 25-29 | 3,748,987 | 3,669,959.4 | 6,598 | 1.76 (1.72-1.80) | 17.98 (17.54-18.41) | 1.007 (0.969-1.047) | |

| 30-34 | 2,407,050 | 2,316,811.4 | 4,159 | 1.73 (1.68-1.78) | 17.95 (17.41-18.50) | Ref. (1.000) | |

| 35-39 | 548,055 | 520,438.4 | 1,262 | 2.30 (2.18-2.43) | 24.25 (22.91-25.59) | 1.345 (1.263-1.432) | |

| > 40 | 73,586 | 70,315.5 | 204 | 2.77 (2.39-3.15) | 29.01 (25.03-32.99) | 1.613 (1.401-1.856) | |

| Father's education | ≥ University | 3,963,915 | 3,823,796.3 | 5,686 | 1.43 (1.40-1.47) | 14.87 (14.48-15.26) | Ref. (1.000) |

| High school | 3,382,991 | 3,314,926.3 | 7,372 | 2.18 (2.13-2.23) | 22.24 (21.73-22.75) | 1.503 (1.452-1.556) | |

| ≤ Middle school | 408,943 | 403,310.3 | 1,593 | 3.90 (3.70-4.09) | 39.50 (37.56-41.44) | 2.677 (2.532-2.830) | |

| Mother's education | ≥ University | 3,229,253 | 3,095,929.6 | 4,458 | 1.38 (1.34-1.42) | 14.40 (13.98-14.82) | Ref. (1.000) |

| High school | 4,175,860 | 4,100,241.9 | 8,789 | 2.10 (2.06-2.15) | 21.44 (20.99-21.88) | 1.500 (1.447-1.555) | |

| ≤ Middle school | 362,143 | 356,542.8 | 1,473 | 4.07 (3.86-4.28) | 41.31 (39.20-43.42) | 2.896 (2.731-3.072) | |

| Father's occupation | Non-manual | 5,812,690 | 5,644,527.9 | 9,659 | 1.66 (1.63-1.69) | 17.11 (16.77-17.45) | Ref. (1.000) |

| Manual | 1,496,785 | 1,464,585.2 | 3,975 | 2.66 (2.57-2.74) | 27.14 (26.30-27.98) | 1.591 (1.533-1.651) | |

| Inactive | 396,132 | 383,400.2 | 954 | 2.41 (2.26-2.56) | 24.88 (23.30-26.46) | 1.452 (1.359-1.552) | |

| Mother's occupation | Non-manual | 1,227,702 | 1,170,790.2 | 1,738 | 1.42 (1.35-1.48) | 14.84 (14.15-15.54) | Ref. (1.000) |

| Manual | 85,996 | 83,195.3 | 257 | 2.99 (2.62-3.35) | 30.89 (27.11-34.67) | 2.090 (1.834-2.383) | |

| Inactive | 6,427,172 | 6,273,296.5 | 12,686 | 1.97 (1.94-2.01) | 20.22 (19.87-20.57) | 1.372 (1.305-1.443) | |

*Infant mortality rate (IMR): the ratio of the number of deaths at less than one year of age per the number of 1,000 live births.

†IMR 95% CI: .

‡Incidence density (ID) of infant deaths: the ratio of the number of deaths at less than one year of age per 10,000 and sum of person-years.

§ID 95% CI: .

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference.

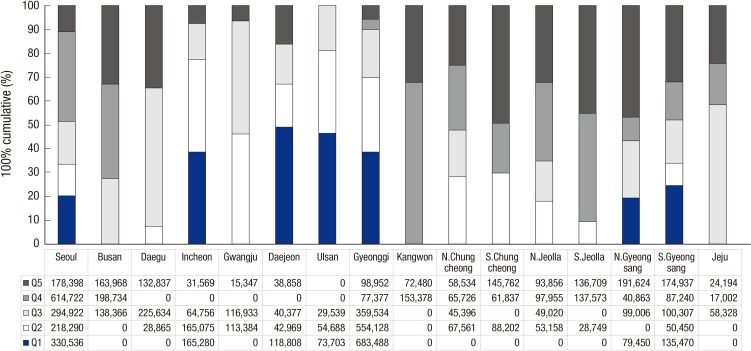

The distribution of regional deprivation quintiles throughout Korea is shown in Fig. 2. The less deprived areas (Q1 and Q2; first and second quintiles) were more commonly found in metropolitan regions, such as Seoul, Gyeonggi, and Incheon. Additionally, the more deprived areas (Q4 and Q5; fourth and fifth quintiles) were more often distributed in the non-metropolitan regions, such as South Jeolla, North Gyeongsang, and South Gyeongsang. The compositions of the deprivation quintiles were distributed unequally throughout the nation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The distribution of regional deprivation quintiles throughout Korea.

Q1, The least deprived quintiles; Q5, The most deprived quintiles; S, South; N, North.

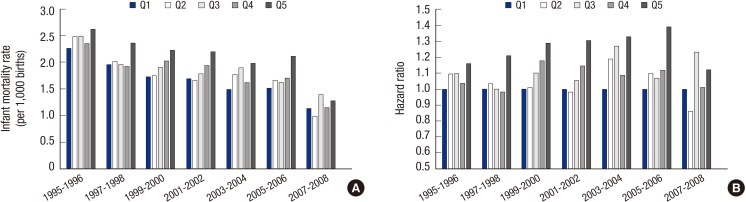

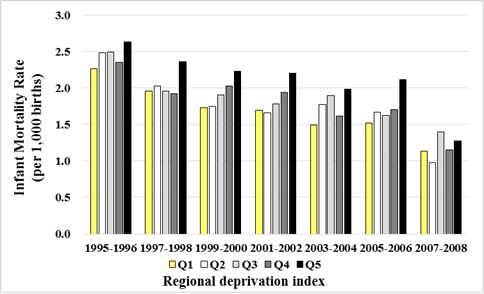

Time trends for the infant mortality rate and hazard ratio according to deprivation quintiles are presented in Fig. 3. The overall trend for the infant mortality rate was a gradual decrease over time from 1995 to 2008. However, inequalities in the infant mortality rate according to the deprivation quintiles persisted at each 2-year interval. The most deprived quintiles (Q5) generally had the highest infant mortality rate. The hazard ratios for infant deaths of the most deprived quintiles (Q5) generally increased with time compared with those of the least deprived quintiles (Q1) in the K index (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Time trends for infant mortality rate and hazard ratio according to the deprivation quintiles. (A) Time trend for the infant mortality rate according to the deprivation quintiles. (B) Time trend for the hazard ratios of infant deaths according to the deprivation quintiles.

Q1, the least deprived quintiles; Q5, the most deprived quintiles; the reference value of the hazard ratio was 1.000 at the Q1 for the K index.

Multilevel survival analysis of infant deaths

To determine the effects of individual- and regional-level variables on infant death, the frailty model of the multilevel survival analysis was conducted, as shown in Table 4. The covariance of regional random effects was 0.0325 (standard error: 0.0050) in model 1. In model 2, the covariance slightly decreased (2.8%) compared with model 1. The likelihood ratio test (LRT) of models 1 and 2 was significant (P < 0.001). After the parental education and occupation variables were added in model 3, the covariance greatly decreased by 68% ([0.0316-0.0101]/0.0316 × 100) compared with model 2. The LRT of models 2 and 3 was significant (P < 0.001). After the regional deprivation variable was added in model 4, the hazard ratios of individual variables slightly decreased compared to model 3. The covariance decreased by 6.9% ([0.0101-0.0094]/0.0101 × 100) compared with model 3. The LRT of models 3 and 4 was not significant (P = 0.168). Model 3, which included individual variables but no regional variables, had greater explanatory power for the risk of infant death than did model 4, which included both individual and regional variables. Despite its significance, the regional deprivation variable had less of an effect on infant deaths than the individual variables, such as parental education and occupation (Table 4).

Table 4. Multilevel survival analysis of infant deaths.

| Variables | Model 1* | Model 2† | Model 3‡ | Model 4§ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Sex | female | Ref. (1.000) | Ref. (1.000) | Ref. (1.000) | |||||

| male | 1.191 (1.153-1.231) | < 0.001 | 1.192 (1.153-1.232) | < 0.001 | 1.192 (1.153-1.232) | < 0.001 | |||

| Gestational age | 0-36 | 2.084 (1.877-2.314) | < 0.001 | 2.105 (1.895-2.338) | < 0.001 | 2.108 (1.898-2.341) | < 0.001 | ||

| 36-37 | 1.321 (1.174-1.488) | < 0.001 | 1.331 (1.181-1.500) | < 0.001 | 1.333 (1.183-1.502) | < 0.001 | |||

| 37-38 | 1.236 (1.117-1.367) | < 0.001 | 1.255 (1.134-1.390) | < 0.001 | 1.256 (1.135-1.391) | < 0.001 | |||

| 38-39 | 1.163 (1.069-1.266) | < 0.001 | 1.170 (1.075-1.274) | < 0.001 | 1.171 (1.076-1.276) | < 0.001 | |||

| 39-40 | 1.032 (0.950-1.121) | 0.460 | 1.043 (0.959-1.133) | 0.328 | 1.043 (0.960-1.134) | 0.319 | |||

| 40-41 | 1.178 (1.091-1.271) | < 0.001 | 1.125 (1.042-1.215) | 0.003 | 1.126 (1.043-1.216) | 0.002 | |||

| 41-42 | Ref. (1.000) | Ref. (1.000) | Ref. (1.000) | ||||||

| 42- | 1.544 (1.330-1.792) | < 0.001 | 1.447 (1.245-1.681) | < 0.001 | 1.442 (1.241-1.676) | < 0.001 | |||

| Birth weight | 0-2000 | 20.184 (18.476-22.050) | < 0.001 | 18.882 (17.278-20.635) | < 0.001 | 18.871 (17.268-20.623) | < 0.001 | ||

| 2000-2500 | 4.001 (3.692-4.335) | < 0.001 | 3.790 (3.495-4.109) | < 0.001 | 3.787 (3.493-4.106) | < 0.001 | |||

| 2500-3000 | 1.920 (1.816-2.030) | < 0.001 | 1.884 (1.781-1.993) | < 0.001 | 1.883 (1.780-1.992) | < 0.001 | |||

| 3000-3500 | 1.191 (1.133-1.252) | < 0.001 | 1.187 (1.129-1.248) | < 0.001 | 1.187 (1.129-1.248) | < 0.001 | |||

| 3500-4000 | Ref. (1.000) | Ref. (1.000) | Ref. (1.000) | ||||||

| 4000- | 0.988 (0.894-1.091) | 0.808 | 0.960 (0.868-1.062) | 0.428 | 0.960 (0.869-1.062) | 0.430 | |||

| Father's education | ≥ University | Ref. (1.000) | Ref. (1.000) | ||||||

| High school | 1.192 (1.141-1.245) | < 0.001 | 1.190 (1.139-1.243) | < 0.001 | |||||

| ≤ Middle school | 1.580 (1.467-1.702) | < 0.001 | 1.572 (1.459-1.694) | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mother's education | ≥ University | Ref. (1.000) | Ref. (1.000) | ||||||

| High school | 1.231 (1.177-1.287) | < 0.001 | 1.229 (1.176-1.286) | < 0.001 | |||||

| ≤ Middle school | 1.659 (1.534-1.794) | < 0.001 | 1.653 (1.528-1.787) | < 0.001 | |||||

| Father's occupation | Non-manual | Ref. (1.000) | Ref. (1.000) | ||||||

| Manual | 1.203 (1.154-1.254) | < 0.001 | 1.198 (1.149-1.249) | < 0.001 | |||||

| Inactive | 1.262 (1.179-1.351) | < 0.001 | 1.258 (1.176-1.346) | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mother's occupation | Non-manual | Ref. (1.000) | Ref. (1.000) | ||||||

| Manual | 1.185 (1.033-1.359) | 0.015 | 1.163 (1.014-1.335) | 0.031 | |||||

| Inactive | 1.101 (1.044-1.161) | < 0.001 | 1.102 (1.046-1.162) | < 0.001 | |||||

| K index quintile | Q1 | Ref. (1.000) | |||||||

| Q2 | 0.996 (0.920-1.078) | 0.913 | |||||||

| Q3 | 1.071 (0.995-1.154) | 0.068 | |||||||

| Q4 | 1.032 (0.957-1.112) | 0.413 | |||||||

| Q5 | 1.116 (1.040-1.196) | 0.002 | |||||||

| Covariance (Standard Error) | 0.0325 (0.0050) | 0.0316 (0.0049) | 0.0101 (0.0025) | 0.0094 (0.0025) | |||||

| PCV∥ (%) | Ref. | 2.8% | 69.1% | 71.0% | |||||

| Likelihood Ratio | 530.0 | 15010.8 | 15675.2 | 15681.7 | |||||

Likelihood ratio test (LRT) of model 1 and 2: χ2=14,480.8, df=13, P<0.001. LRT of model 2 and 3: χ2=664.4, df=8, P<0.001. LRT of model 3 and 4: χ2=6.5, df=4, P=0.168. *Model 1 was default model with regional random effects; †Model 2 added sex, gestational age and birth weight variables; ‡Model 3 added sex, gestational age, birth weight, parental education and parental occupation variables; §Model 4 added sex, gestational age, birth weight, parental education, parental occupation and K index variables. PCV, proportional change in variance; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference.

There were interactive effects between the deprivation quintiles (Q1 and Q5) and socioeconomic variables, such as parental education and occupation. The risk of infant deaths increased when higher regional deprivation was combined with lower parental education or with manual occupation (Table 5).

Table 5. The joint effects of deprivation quintiles and socioeconomic variables.

| K index | Socioeconomic variables | Births | Infant deaths | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Father's education | ||||

| Q1 | ≥ University | 934,065 | 1,299 | Ref. (1.000) |

| High school | 598,600 | 1,217 | 1.448 (1.365-1.537) | |

| ≤ Middle school | 49,073 | 192 | 2.777 (2.407-3.203) | |

| Q5 | ≥ University | 674,026 | 1,019 | 1.089 (1.021-1.161) |

| High school | 749,092 | 1,742 | 1.657 (1.575-1.744) | |

| ≤ Middle school | 129,026 | 584 | 3.213 (2.956-3.493) | |

| Mother's education | ||||

| Q1 | ≥ University | 771,701 | 1,064 | Ref. (1.000) |

| High school | 769,016 | 1,490 | 1.326 (1.256-1.401) | |

| ≤ Middle school | 42,994 | 162 | 2.575 (2.205-3.008) | |

| Q5 | ≥ University | 551,167 | 798 | 1.008 (0.937-1.083) |

| High school | 888,266 | 2,037 | 1.570 (1.497-1.647) | |

| ≤ Middle school | 114,586 | 527 | 3.147 (2.882-3.435) | |

| Father's occupation | ||||

| Q1 | Non-manual | 1,274,031 | 1,995 | Ref. (1.000) |

| Manual | 237,457 | 571 | 1.811 (1.665-1.970) | |

| Inactive | 63,139 | 134 | 1.610 (1.358-1.910) | |

| Q5 | Non-manual | 1,031,517 | 1,889 | 1.386 (1.320-1.455) |

| Manual | 414,831 | 1,202 | 2.186 (2.060-2.321) | |

| Inactive | 91,610 | 237 | 1.967 (1.730-2.237) | |

| Mother's occupation | ||||

| Q1 | Non-manual | 268,890 | 355 | Ref. (1.000) |

| Manual | 7,203 | 16 | 1.339 (0.820-2.187) | |

| Inactive | 1,302,108 | 2,330 | 1.059 (1.012-1.108) | |

| Q5 | Non-manual | 227,296 | 350 | 0.922 (0.828-1.026) |

| Manual | 47,046 | 174 | 2.190 (1.885-2.544) | |

| Inactive | 1,274,662 | 2,836 | 1.316 (1.262-1.373) |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; Q1, the least deprived quintiles; Ref, reference; Q5, the most deprived quintiles.

DISCUSSION

The main conclusions of our study are described as follows. We constructed the K index using PCA tailored to the context of Korea. The K index functioned as the deprivation index estimating the regional socioeconomic status, and the validity and reliability of the index were confirmed. Although the infant mortality rate generally decreased over time from 1995 to 2008 in Korea, inequalities according to the deprivation quintiles persisted. We found that the regional deprivation variables were important factors in infant deaths. Despite its significance, the regional deprivation variable made less of a contribution to infant death than did individual variables such as the infants’ sex, gestational age, and weight and the parents’ age, education and occupation.

Our study demonstrated that regional deprivation was associated with the infant mortality rate. These results are similar to those found in several previous studies. Guildea et al. (24) showed that as the deprivation score increased (deprivation became more severe), the infant mortality rate increased. Singh and Kogan (25) demonstrated that the inequalities in the patterns of infant mortality according to the deprivation quintiles were consistent over the past three decades in the US.

Several articles demonstrated that the infant mortality rate was associated with socioeconomic status. Finch (2) demonstrated that the infant mortality rate was inversely related to income. Leon et al. (26) showed that the risk of infant mortality in the lower social classes was higher than that in the higher social classes. Arntzen et al. (27) demonstrated that there was a higher rate of mortality among infants with parents with a low level of education. Our study showed that the risk of infant death increased when the parents had less than a middle school level of education and manual occupations. Socioeconomic status was an important factor in estimating infant deaths using the deprivation index.

According to our results, regional deprivation was an important factor in estimating infant deaths. However, the regional deprivation variable made less of a contribution to infant death than did the individual variables. These results are similar to those presented in several previous studies. Calling et al. (28) demonstrated that a high level of neighborhood deprivation is associated with high infant mortality rates. However, after adjusting for individual socioeconomic variables, neighborhood deprivation was no longer statistically significant; thus, the individual-level variables were important than the community-level variables in explaining infant mortality. Adedini et al. (29) also demonstrated that individual-level variables were more important than community-level variables in explaining infant mortality. However, community-level variables were more important than individual-level variables in explaining child mortality. Adedini et al. (29) deduced that the interaction between the child and the community environment was likely to be greater in childhood (12-59 months) than in infancy (< 12 months).

We deduced the mechanism through which regional deprivation and individual variables affect infant death. Several articles demonstrated that individual variables strongly influence infant mortality. Glinianaia et al. (30) demonstrated that very low baby weight (< 1,500 g) and extremely preterm delivery (< 28 weeks) are strongly associated with infant mortality. Our study demonstrated that parental education and occupation variables influence infant mortality. We deduced that a low level of education and manual occupation influenced infant mortality through low income and unmet material needs. More research is needed to determine whether there is a causal relationship between regional deprivation and infant death.

In Table 2, we found that excess infant mortality rate was unequally represented throughout the county. We deduced that the differences in the average economic status, accessibility of the regional health care system, population structure and types of occupation between the metropolitan and local provinces resulted in the differences in infant death.

To reduce the differences in health problems such as infant deaths according to regional deprivation, policy should be established with consideration of more deprived areas and people. A regional perinatal care system and emergency medical system should be adequately established in more deprived regions. A monitoring and surveillance system for high-risk people should be adequately operated in more deprived regions. In particular, pregnant women and neonates in more deprived regions should be cared for and supported by government and regional administrations. In addition, the low accessibility of the medical care system in more deprived regions should be improved through the establishment of community health centers. To reduce differences in health problems across regions, regional deprivation should be considered.

We conducted PCA to construct the regional deprivation index. PCA methods were used to convert originally correlated variables into uncorrelated variables that were linear combinations with the original variables by different weighting. The weighting was determined by a statistical method based on the data. The Carstairs and Townsend indices were constructed by averaging each of four variables by the same weighting.

Several articles used PCA to construct deprivation indices worldwide. Havard et al. (12) constructed a deprivation index using the PCA method. The internal validity of their index was evaluated with Cronbach’s alpha (0.92). Convergent validity was evaluated by performing a Pearson’s correlation of their index and the Carstairs index (0.96, P < 0.01) (12). The findings of this study are similar to our results. In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha of the K index was 0.973, and the Pearson’s correlation between the K and Carstairs indices was 0.716 (P < 0.001). However, our Pearson’s correlation coefficient value was slightly lower than that in the study of Havard et al. (12).

Our study has a limitation that relates to the possible instability in the birth cohort data. We found that births from 2005 to 2008 sharply increased compared with births in previous years. By performing a detailed analysis, we found that some cases had missing values for parental socioeconomic variables. Consequently, those cases were deleted (25,885 cases, 0.33%). Compared with the official results from the Korean National Statistics Office, infant deaths were under-reported in the birth cohort data. Despite these disadvantages, data on fourteen years of birth cohorts (7,784,804 cases) from Korea are uniquely valuable. Therefore, we conducted our study using these data.

In future studies, new and more suitable deprivation indices should be developed for the Korean context. Relatively stable and recent birth cohort data should be analyzed. In addition, by using a newly developed deprivation index, we can evaluate the possible association between disease and deprivation.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (0720340).

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Conception and design: Son M, Yun JW, Kim YJ. Acquisition of data: Son M. Analysis and interpretation of data: Yun JW, Son M, Kim YJ. Manuscript composition: Yun JW, Son M, Kim YJ. Approval of the manuscript results and conclusions: all authors.

References

- 1.Olson ME, Diekema D, Elliott BA, Renier CM. Impact of income and income inequality on infant health outcomes in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1165–1173. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finch BK. Early origins of the gradient: the relationship between socioeconomic status and infant mortality in the United States. Demography. 2003;40:675–699. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh GK, Yu SM. Infant mortality in the United States: trends, differentials, and projections, 1950 through 2010. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:957–964. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDorman MF, Mathews T. Recent trends in infant mortality in the United States. NCHS Data Brief. 2008:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Son M, Oh J, Choi YJ, Kong JO, Choi J, Jin E, Jung ST, Park SJ. The effects of the parents’ social class on infant and child death among 1995-2004 birth cohort in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2006;39:469–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh GK, Siahpush M, Azuine RE, Williams SD. Increasing area deprivation and socioeconomic inequalities in heart disease, stroke, and cardiovascular disease mortality among working age populations, United States, 1969-2011. Int J MCH AIDS. 2015;3:119–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carstairs V, Morris R. Deprivation: explaining differences in mortality between Scotland and England and Wales. BMJ. 1989;299:886–889. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6704.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deprivation TP. J Soc Policy. 1987;16:125–146. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salmond C, Crampton P, Sutton F. NZDep91: a New Zealand index of deprivation. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1998;22:835–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tello JE, Jones J, Bonizzato P, Mazzi M, Amaddeo F, Tansella M. A census-based socio-economic status (SES) index as a tool to examine the relationship between mental health services use and deprivation. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:2096–2105. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messer LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS, Eyster J, Holzman C, Culhane J, Elo I, Burke JG, O’Campo P. The development of a standardized neighborhood deprivation index. J Urban Health. 2006;83:1041–1062. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9094-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Havard S, Deguen S, Bodin J, Louis K, Laurent O, Bard D. A small-area index of socioeconomic deprivation to capture health inequalities in France. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:2007–2016. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pampalon R, Raymond G. A deprivation index for health and welfare planning in Quebec. Chronic Dis Can. 2000;21:104–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahn KO, Shin SD, Hwang SS, Oh J, Kawachi I, Kim YT, Kong KA, Hong SO. Association between deprivation status at community level and outcomes from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a nationwide observational study. Resuscitation. 2011;82:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park EJ, Kim H, Kawachi I, Kim IH, Cho SI. Area deprivation, individual socioeconomic position and smoking among women in South Korea. Tob Control. 2010;19:383–390. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yi O, Kwon HJ, Kim D, Kim H, Ha M, Hong SJ, Hong YC, Leem JH, Sakong J, Lee CG, et al. Association between environmental tobacco smoke exposure of children and parental socioeconomic status: a cross-sectional study in Korea. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:607–615. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J, Lee WY, Noh M, Khang YH. Does a geographical context of deprivation affect differences in injury mortality? A multilevel analysis in South Korean adults residing in metropolitan cities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68:457–465. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi MH, Cheong KS, Cho BM, Hwang IK, Kim CH, Kim MH, Hwang SS, Lim JH, Yoon TH. Deprivation and mortality at the town level in Busan, Korea: an ecological study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2011;44:242–248. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2011.44.6.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howe N, Jackson R, Nakashima K. The aging of Korea: demographics and retirement policy in the land of the morning calm. Washington, D.C.: Center For Strategic and International Studies; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin C, Shaw I. Social policy in South Korea: cultural and structural factors in the emergence of welfare. Soc Policy Adm. 2003;37:328–341. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CJ. Korean education fever and private tutoring. KEDI J Educ Policy. 2005;2:99–107. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pampalon R, Hamel D, Gamache P, Simpson A, Philibert MD. Validation of a deprivation index for public health: a complex exercise illustrated by the Quebec index. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014;34:12–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juhn YJ, Sauver JS, Katusic S, Vargas D, Weaver A, Yunginger J. The influence of neighborhood environment on the incidence of childhood asthma: a multilevel approach. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:2453–2464. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guildea ZE, Fone DL, Dunstan FD, Sibert JR, Cartlidge PH. Social deprivation and the causes of stillbirth and infant mortality. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:307–310. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.4.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh GK, Kogan MD. Persistent socioeconomic disparities in infant, neonatal, and postneonatal mortality rates in the United States, 1969-2001. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e928–e939. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leon DA, Vågerö D, Olausson PO. Social class differences in infant mortality in Sweden: comparison with England and Wales. BMJ. 1992;305:687–691. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6855.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arntzen A, Samuelsen SO, Bakketeig LS, Stoltenberg C. Socioeconomic status and risk of infant death. A population-based study of trends in Norway, 1967-1998. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:279–288. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calling S, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Socioeconomic inequalities and infant mortality of 46,470 preterm infants born in Sweden between 1992 and 2006. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2011;25:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adedini SA, Odimegwu C, Imasiku EN, Ononokpono DN, Ibisomi L. Regional variations in infant and child mortality in Nigeria: a multilevel analysis. J Biosoc Sci. 2015;47:165–187. doi: 10.1017/S0021932013000734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glinianaia SV, Rankin J, Pearce MS, Parker L, Pless-Mulloli T. Stillbirth and infant mortality in singletons by cause of death, birthweight, gestational age and birthweight-for-gestation, Newcastle upon Tyne 1961-2000. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2010;24:331–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2010.01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]