Abstract

Background

Certain Chinese medicine (CM) herbs and acupuncture may protect against Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, there is a lack of research regarding the use of CM in patients with AD. The aim of this study was to investigate CM usage patterns in patients with AD, and identify the Chinese herbal formulae most commonly used for AD.

Methods

This retrospective, nationwide, population-based cohort study was conducted using a randomly sampled cohort of one million patients, selected from the National Health Insurance Research Database between 1997 and 2008 in Taiwan. CM use and the top ten most frequently prescribed formulae for treating AD were assessed, including average formulae dose and frequency of prescriptions. Demographic characteristics, including sex, age and insurance level were examined, together with geographic location. Existing medical conditions with the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, and medications associated with CM were also examined. Factors associated with CM use were analyzed by multiple logistic regressions.

Results

The cohort included 1137 newly diagnosed AD patients, who were given conventional treatment for AD between 1997 and 2008. Among them, 78.2 % also used CM treatments, including Chinese herbal remedies, acupuncture and massage manipulation. Female patients (aOR 1.57 with 95 % CI 1.16–2.13) and those living in urban areas (aOR 3.00 with 95 % CI 1.83–4.90 in the middle of Taiwan) were more likely to use CM. After adjusting for demographic factors, AD patients suffering from the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia were more likely to seek CM treatment than those with no symptoms (aOR 2.26 with 95 % CI 1.48–3.43 in patients suffering more than three symptoms). Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang and Ji-Sheng-Shen-Qi-Wan were the two formulae most frequently prescribed by CM practitioners for treating AD.

Conclusion

Most people with AD who consumed herbal products used supplement qi, nourish the blood, and quiet the heart spirit therapy as complementary medicines to relieve AD-related symptoms, in addition to using standard anti-AD treatments.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13020-016-0086-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by substantial memory impairment, aphasia, apraxia, agnosia and function disturbance [1]. AD is the most common cause of dementia in older people and accounts for 60–80 % of reported dementia cases in the World [2]. Although psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions can be effective for alleviating AD-related symptoms [3], there is currently no curative treatment for AD.

It has been reported that some Chinese herbs may protect brain cells against AD [4, 5]. However, clinical evidence regarding the efficacy of Chinese medicine (CM) for treating AD is limited. This study therefore aims to investigate the extent to which CM is used by patients suffering from AD, and to identify the most common Chinese herbal formulae used by AD patients to treat their symptoms.

Methods

This study was approved by the Taipei City Hospital Institutional Review Board under study number TCHIRB-1020816-E (Additional file 1) and National Health Research Institutes under study number NHIRD-103-091 (Additional file 2). The research and associated reporting have been conducted in accordance with conventional ethical principles to protect the identities of the patients involved.

Data resources

This retrospective, nationwide, population-based cohort study was conducted using a randomly sampled cohort of one million patients, selected from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) between 1997 and 2008 in Taiwan. The National Health Insurance (NHI) system covers over 97 % of the population of Taiwan and provides full reimbursement to its members for treatments based on CM, including Chinese herbal products, acupuncture, moxibustion and traumatology manipulative therapies. The NHI also holds all of the medical records for CM treatments prescribed by licensed CM practitioners [6].

One million patient records were randomly selected from those of the 23 million Taiwanese people currently insured under the NHI system. No significant differences were observed in the demographic distribution between the random sample and the original NHIRD. The medical records used in this study were collected for the dates between the 1st of January, 1996 and the 31st of December, 2008. The NHIRD database contained complete data pertaining to clinical visits, and hospitalization records, including visit date, hospital, physician specialist, major diagnoses and the dosage and frequency of any medicines prescribed. The Bureau of National Health Insurance requires physicians to record major diagnoses according to the format described in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).

Study sample

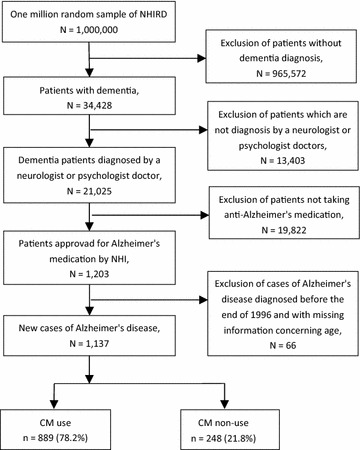

Figure 1 shows a flowchart describing of the sample selection process. First, all patients without dementia (ICD-9 codes: 290.0, 290.1, 290.2, 290.3, 290.4, 294.1, 294.2 and 331) were excluded (n = 965,572). Second, we excluded patients with a dementia diagnosis not made by a qualified neurologist or psychologist (n = 13,403), along with patients that did not receive anti-AD treatment (n = 19,822). Doctors in Taiwan are requested by the Bureau of National Health Insurance to only prescribe anti-AD drugs to patients that fulfill the criteria outlined by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS), the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV-TR). Finally, cases of AD diagnosed before the end of 1996 were excluded from the current study, as well as those without complete NHI reimbursement data (n = 66) to ensure that all of the patients represented newly diagnosed cases of AD. Upon completion of this exclusion process, we had a study cohort consisting of 1137 patients.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart detailing the recruitment of subjects from random sample of one million patients from the NHIRD between 1997 and 2008

Study variables

Several demographic factors were selected from previous studies [7]. The patients were categorized into six different age groups: <45, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84 and ≥85 years of age. The geographic locations of the patients were sorted into seven different regions with similar regional environments: Taipei City and Kaohsiung City, the Northern, Central, Eastern and Southern regions of Taiwan, and the outlying islands.

The amount of money to which each patient was insured was divided into four levels: 0, 1–19,999, 20,000–39,999 and >40,000 new Taiwanese dollars. The “0” insured level included unemployed and retired patients, for whom the insurance costs were covered by the government or other family members.

The NHIRD database was searched for diagnosis and treatment records relating to the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), including delirium (ICD9 codes: 290.11, 290.3 and 290.41), delusions (ICD9 codes: 290.20, 290.12 and 290.42), depression (ICD9 codes: 290.13, 290.21 and 290.43), sleep disturbances (ICD9 codes: 780.5 and 307.4), hallucination (ICD9 codes: 7801, 2913 and 2928) and behavioral disturbances (ICD9 codes: 294.11 and 294.21). The reimbursement database contains all of the important details relating to the prescription of conventional medicines for treating AD. The types of prescription drugs used to treat AD were categorized as follows: donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, memantine, deprenyl, antipsychotic, antimanic, anxiolytic and antidepressant.

The comorbidities of the patients were categorized using the icd-9-cm codes. Notably, the results of previous studies have shown that some comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus (icd9 codes: 249 and 250), hypertension (icd9 codes: 401–405), hyperlipidemia (icd9 codes: 272), chronic kidney disease (icd9 codes: 585, 586 and 588), cerebral vascular accident (icd9 codes: 430–438) and atherosclerosis (icd9 codes: 440), can affect the prognosis and treatment of patients diagnosed with AD.

Chinese medicine treatment

Chinese herbal products (CHPs) composed of one or more herbs (i.e., herbal formulae), which are covered by the NHI system, are more widely adopted by Taiwanese patients than any other form of CM. [8] Information pertaining to CHPs was obtained from the Department of Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy (DCMP), Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan, including the name and ingredients of their herbal formula, as well as their pharmaceutical effects, DCMP manufacturing code and manufacturer. CHPs with the same good manufacturing practices and DCMP standards were sorted into the same group [9]. The acupuncture therapy including acupoint and frequency and massage manipulation and treatment position were also record by the NHI system.

Statistical analysis

The factors associated with the CM treatments used in the current study were analyzed using multiple logistic regression with a significance level of α = 0.05. An odds ratio was used to quantify the relationships between the different conditions and CM use. All of the odds ratios were adjusted based on the demographic factors described above. Version 9.3 of the SAS statistical analysis software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for data management and analysis.

Results

The NHIRD of outpatient claims contained information pertaining to the claims of 1137 patients with AD from 1997 to 2008. Among them, 889 (78.2 %) AD patients used CM outpatient services. The mean age of non-CM users was slightly higher than that of CM users.

Table 1 shows details concerning the demographic and medication distributions of the CM and non-CM users. After adjusting for demographic factors, the results clearly showed that AD patients suffering from one or more BPSD (one symptom: OR = 0.90, 95 % CI 0.57–1.44; two symptoms: OR = 1.94, 95 % CI 1.24–3.05; three or more symptoms: OR = 2.26, 95 % CI 1.48–3.43) were more likely to seek CM treatment than those with no BPSD. Female patients and those living in urban areas were more likely to seek CM treatment than male patients and those living in rural areas. No discernible difference was observed in CM use between AD patients suffering from one or more comorbidities (one: OR = 1.1, 95 % CI 0.47–2.58; two: OR = 0.91, 95 % CI 0.41–2.01; and three or more types: OR = 1.76, 95 % CI 0.83–3.74) and those with no comorbidity.

Table 1.

Demographic and medication characteristics and results of multiple logistic regression for CM use among patients with Alzheimer’s disease

| Characteristics | CMa users | CMa non-users | aORb (95 % CIc) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | 889 (78.2 %) | 248 (21.8 %) | |

| Age at diagnosis (incidence rate) | |||

| <45 (0.001 %) | 7 (0.8 %) | 2 (0.8 %) | 0.78 (0.15–4.05) |

| 45–54 (0.036 %) | 27 (3 %) | 2 (0.8 %) | 3.64 (0.80–16.53) |

| 55–64 (0.246 %) | 115 (12.9 %) | 27 (10.9 %) | 1 |

| 65–74 (1.185 %) | 309 (34.8 %) | 92 (37.1 %) | 0.74 (0.45–1.22) |

| 75–84 (7.105 %) | 381 (42.9 %) | 107 (43.1 %) | 0.83 (0.51–1.36) |

| ≥85 (17.942 %) | 50 (5.6 %) | 18 (7.3 %) | 0.61 (0.30–1.24) |

| Mean years | 72.8 | 73.8 | |

| Sex | |||

| Female (0.13 %) | 530 (59.6 %) | 121(48.8 %) | 1.57 (1.16–2.13) |

| Male (0.10 %) | 359 (40.4 %) | 127 (51.2 %) | 1 |

| Insured region | |||

| Taipei city | 137 (15.4 %) | 61 (24.6 %) | 1 |

| Kaohsiung city | 71 (8 %) | 14 (5.6 %) | 2.38 (1.24–4.57) |

| Northern Taiwan | 200 (22.5 %) | 58 (23.4 %) | 1.65 (1.07–2.54) |

| Middle Taiwan | 209 (23.5 %) | 32 (12.9 %) | 3.00 (1.83–4.90) |

| Southern Taiwan | 240 (27 %) | 78 (31.5 %) | 1.39 (0.91–2.12) |

| Eastern Taiwan | 21 (2.4 %) | 4 (1.6 %) | 2.48 (0.80–7.64) |

| Outlying island | 11 (1.2 %) | 1 (0.4 %) | 4.98 (0.61–40.51) |

| Insured amount (NT$d) | |||

| 0 | 353 (39.7 %) | 94 (37.9 %) | 0.99 (0.68–1.45) |

| 1–19,999 | 486 (54.7 %) | 140 (56.5 %) | 1 |

| 20,000–39,999 | 32 (3.6 %) | 8 (3.2 %) | 0.90 (0.38–2.15) |

| ≥400,000 | 18 (2 %) | 6 (2.4 %) | 0.77 (0.28–2.13) |

| Numbers of anti-Alzheimer’s or BPSD drugs | |||

| 1 | 28 (3.1 %) | 8 (3.2 %) | 1 |

| 2 | 145 (16.3 %) | 51 (20.6 %) | 0.81 (0.35–1.90) |

| 3 | 318 (35.8 %) | 87 (35.1 %) | 1.04 (0.46–2.37) |

| ≥4 | 398 (44.8 %) | 102 (41.1 %) | 1.12 (0.49–2.52) |

| Numbers of dementia BPSDe | |||

| 0 | 102 (11.5 %) | 46 (18.5 %) | 1 |

| 1 | 122 (13.7 %) | 61 (24.6 %) | 0.90 (0.57–1.44) |

| Delirium | 4 | 3 | |

| Delusions | 13 | 7 | |

| Depression | 18 | 12 | |

| Behavioral disturbance | 4 | 2 | |

| Sleep disturbances | 83 | 37 | |

| Hallucination | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 250 (28.1 %) | 58 (23.4 %) | 1.94 (1.24–3.05) |

| Delirium + delusions | 8 | 7 | |

| Delirium + depression | 2 | 1 | |

| Delirium + behavioral | 0 | 0 | |

| Delirium + sleep | 12 | 6 | |

| Delirium + hallucination | 0 | 0 | |

| Delusions + depression | 10 | 6 | |

| Delusions + behavioral | 0 | 0 | |

| Delusions + sleep | 21 | 11 | |

| Delusions + hallucination | 0 | 0 | |

| Depression + behavioral | 1 | 0 | |

| Depression + sleep | 21 | 8 | |

| Depression + hallucination | 0 | 1 | |

| Behavioral + sleep | 6 | 0 | |

| Behavioral + hallucination | 0 | 0 | |

| Sleep + hallucination | 169 | 22 | |

| ≥3 | 415 (46.7 %) | 83 (33.5 %) | 2.26 (1.48–3.43) |

| Numbers of comorbidity | |||

| 0 | 25 (2.81 %) | 10 (4.03 %) | 1 |

| 1 | 74 (8.32 %) | 27 (10.89 %) | 1.1 (0.47–2.58) |

| 2 | 148 (16.7 %) | 65 (26.21 %) | 0.91 (0.41–2.01) |

| ≥3 | 642 (72.2 %) | 146 (58.87 %) | 1.76 (0.83–3.74) |

a CM refers to Chinese medicine

b aOR refers to adjust odds ratio

c CI refers to confidence interval

d NT$ refers to new Taiwan dollars, of which 1 US $ = 30 NT$

e BPSD refers to behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia

Analyses of the major disease categories for all CM visits are summarized in Table 2. These results show that 18,138 (73.3 %) visits were treated with prescribed CHPs, whereas the remaining visits were treated with acupuncture and traumatology manipulative therapies. AD patients tended to use CHPs rather than acupuncture. “Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions” was cited as the most common reason for using CM (20.2 %, 5011 visits), followed sequentially by “diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue” (20.0 %, 4962 visits), “diseases of the respiratory system” (14.3 %, 3542 visits) and “diseases of the digestive system” (12.2 %, 3024 visits). Of the AD patients evaluated in the current study, 9.3 % sought CMs with the aim of treating their “mental disorders, diseases of the nervous system and sense organs”.

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of Chinese medicine visits by major disease categories (according to 9th ICD codes) in Alzheimer’s patients from 1997 to 2008 in Taiwan

| Major disease category | ICD-9-CM code range | Number of visits (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese herbal remedies | Acupuncture, or manipulative therapies | Total of CM | ||

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | 001–139 | 42 (0.2) | 5 (0.02) | 47 (0.2) |

| Neoplasms | 140–239 | 119 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 119 (0.5) |

| Endocrine, nutritional, blood and metabolic diseases, and immunity disorders | 240–289 | 799 (3.2) | 25 (0.1) | 824 (3.3) |

| Mental disorders, diseases of the nervous system and sense organs | 290–389 | 1901 (7.7) | 389 (1.6) | 2290 (9.3) |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 390–459 | 1006 (4.1) | 162 (0.7) | 1168 (4.7) |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 460–519 | 3449 (13.9) | 93 (0.4) | 3542 (14.3) |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 520–579 | 2954 (11.9) | 70 (0.3) | 3024 (12.2) |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 580–677 | 789 (3.2) | 40 (0.2) | 829 (3.3) |

| Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 680–709 | 327 (1.3) | 9 (0.04) | 336 (1.4) |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 710–739 | 2016 (8.1) | 2946 (11.9) | 4962 (20.0) |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions | 780–799 | 3877 (15.7) | 1134 (4.6) | 5011 (20.2) |

| Injury and poisoning | 800–999 | 77 (0.3) | 852 (3.4) | 929 (3.8) |

| Supplementary classification | V01–V82, E800–E999 | 0 (0) | 4 (0.02) | 4 (0.02) |

| Othersa | 322 (1.3) | 848 (3.4) | 1170 (4.7) | |

| Total | 18,138 (73.3) | 6613 (26.7) | 24,751 (100.0) | |

a Other includes ICD-9-CM code range 740–779 and missing/error data

Table 3 shows the details of the CHPs most frequently prescribed by CM practitioners for treating mental disorders and diseases of the nervous system. The results show that Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang was the most frequently prescribed CHP, followed by Ji-Sheng-Shen-Qi-Wan, Ma-Zi-Ren-Wan and Tian-Wang-Bu-Xin-Dan. The potential effects of the herbs contained in the 10 most common formulae are shown in Table 4. It is noteworthy that several herbs, including Ginseng Radix(Ren-Shen) and Angelicae Sinensis Radix Integra(Dang-Gui), appeared repeatedly in formulae reported to be effective against AD. Table 5 shows that 77.1 % of the AD patients consumed Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang during the period covered by the current study. After adjusting for demographic factors, the results revealed that female AD patients (OR = 1.23, 95 % CI 1.04–1.57) were more likely to consume Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang than male patients.

Table 3.

Ten most commonly used herbal formulae prescribed by CM practitioners for treating mental disorders, diseases of the nervous system and sense organs (total prescriptions: 1901)

| Herbal formulae | English name | Average formulae dose (g/day) | Ren-Shen CHF dose (g/day) | Ren-Shen herbs (g/day) | Dang-Qui CHF dose (g/day) | Dang-Qui herbs (g/day) | Frequency of prescriptions (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang | Center-supplementing Qi-boosting decoction | 5.3 | 1.4 | 8.0 | 0.9 | 5.6 | 629 (33.1) |

| Ji-Sheng-Shen-Qi-Wan | Life saver kidney Qi Pill | 5.1 | – | – | – | – | 538 (28.3) |

| Ma-Zi-Ren-Wan | Cannabis fruit pill | 4.8 | – | – | – | – | 511 (26.9) |

| Tian-Wang-Bu-Xin-Dan | Celestial emperor heart-supplementing elixir | 4.2 | 0.7 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 8.1 | 476 (25) |

| Gan-Mai-Da-Zao-Tang | Licorice, wheat, and jujube decoction | 3.9 | – | – | – | – | 421 (22.1) |

| Sheng-Mai-San | Pulse-engendering powder | 2.6 | 1.5 | 8.6 | – | – | 396 (20.8) |

| Tian-Ma-Gou-Teng-Yin | Gastrodia and uncaria beverage | 5.5 | – | – | – | – | 381 (20) |

| Liu-Wei-Di-Huang-Wan | Six-ingredient rehmannia pill | 2.1 | – | – | – | – | 336 (17.7) |

| Qi-Bao-Mei-Ran-Dan | Seven-jewel beard-blackening elixir | 3.5 | – | – | 0.9 | 5.6 | 284 (14.9) |

| Tao-Hong-Si-Wu-Tang | Peach Kernel and Carthamus four agents decoction | 2.2 | – | – | 0.4 | 2.5 | 258 (13.6) |

Table 4.

Potential effects of the herbs contained in the ten most common formulae prescribed by CM practitioners for treating Alzheimer’s disease

| Herbal formulae | Constituents |

|---|---|

| Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang a, b, c, d | Astragali Radix Cruda (Huang-qi),Ginseng Radix (Ren-shen) a, b, c, d , Glycyrrhizae Radix cum Liquido Fricta (Zhi-gan-cao), Atractylodis MacrocephalaeRhizoma (Bai-zhu), Angelicae Sinensis Radix Integra (Dang-gui) a, c, d , CitriReticulatae Pericarpium (Chen-pi), Cimicifugae Rhizoma (Sheng-ma), Bupleuri Radix (Chai-hu), Zingiberis Rhizoma Recens (Sheng-jiang), Jujubae Fructus (Da-zao) |

| Ji-Sheng-Shen-Qi-Wan a, c | Rehmanniae Radix (Di-huang), Poria cum (Fu-ling) a, c , Corni Fructus (Shan-zhu-yu), Dioscoreae Rhizoma (Shan-yao), Moutan Cortex (Mu-dan-pi), Alismatis Rhizoma (Ze-xie), Aconiti Radix Lateralis (Fu-zi), Cinnamomi Cortex (Rrou-gui), Achyranthis Bidentatae Radix (Huai-niu-xi), Plantaginis Semen (Che-qian-zi) |

| Ma-Zi-Ren-Wan a, c | Cannabis Fructus (Ma-zi-ren), Rhei Radix et Rhizoma (Da-huang) c , Paeoniae Radix Alba (Bai-shao) a , Aurantii Fructus Immaturus (Zhi-shi), Magnoliae Officinalis Cortex (Hou-po), Armeniacae Semen (Xing-ren) |

| Tian-Wang-Bu-Xin-Dan a, b, c, d | Rehmanniae Radix (Di-huang), Ginseng Radix (Ren-shen) a, b, c, d , Polygalae Radix (Yuan-zhi) c , Scrophulariae Radix(Xuan-shen), Platycladi Semen (Bai-zi-ren), Platycodonis Radix (Jie-geng), Asparagi Radix (Tian-men-dong), Salviae Miltiorrhizae Radix (Dan-shen) c , Ziziphi Spinosi Semen (Suan-zao-ren), Ophiopogonis Radix (Mai-men-dong), Poria cum PiniRadice (Fu-shen) a, c , Angelicae Sinensis Radix Integra (Dang-gui) a, c, d , Schisandrae Fructus (Wu-wei-zi) |

| Gan-Mai-Da-Zao-Tang | Glycyrrhizae Radix Cruda (Zhi-gan-cao),Jujubae Fructus (Da-zao), Tritici Semen (Xiao-mai) |

| Sheng-Mai-San a, b, c, d | Ginseng Radix (Ren-shen) a, b, c, d ,Ophiopogonis Radix (Mai-men-dong), Schisandrae Fructus (Wu-wei-zi) |

| Tian-Ma-Gou-Teng-Yin a, c | Gastrodiae Rhizoma (Tian-ma) c , Uncariae Ramulus cum Uncis (Gou-teng) a , Haliotidis Concha (Shi-jue-ming), Gardeniae Fructus(Shan-zhi-zi), Scutellariae Radix (Huang-qin), Eucommiae Cortex (Du-zhong), Loranthiseu Visci Ramus (Sang-ji-sheng), LeonuriHerba (Yi-mu-cao), PolygoniMultiflori Caulis (Ye-jiao-teng), Achyranthis Bidentatae Radix (Huai-niu-xi), Poria cum Pini Radice (Fu-shen) a, c |

| Liu-Wei-Di-Huang-Wan c | Rehmanniae Radix (Di-huang), Poria cum (Fu-ling) c , CorniFructus (Shan-zhu-yu), DioscoreaeRhizoma (Shan-yao), Moutan Cortex (Mu-dan-pi), AlismatisRhizoma (Ze-xie) |

| Qi-Bao-Mei-Ran-Dan a, c, d | PolygoniMultiflori Radix (He-shou-wu), AchyranthisBidentatae Radix (Huai-niu-xi), AngelicaeSinensis Radix Integra (Dang-gui) a, c, d , Poria cum (Fu-ling), Cuscutae Semen (Tu-si-zi), LyciiFructus (Gou-qi-zi), PsoraleaeFructus (Po-gu-zhi) |

| Tao-Hong-Si-Wu-Tang a, c, d | Persicae Semen (Yao-ren), Carthamustinctorius Flos (Hong-hua), Angelicae Sinensis Radix Integra (Dang-gui) a, c, d , Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuan-xiong), Paeoniae Radix Alba (Bai-shao) a , Rehmanniae Radix (Di-huang) |

a Formula containing a single herb that might promote the neurotransmitter acetylcholine

b Formula containing a single herb that might inhibit the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor

c Formula containing a single herb that might reduce the β-amyloid

d Formulae containing a single herb that might decrease the Tau protein

Table 5.

Demographic characteristics of Bu–Zhong–Yi–Qi–Tang use among patients with Alzheimer’s disease

| Characteristics | Bu–Zhong–Yi–Qi–Tang users (%) | CMa users not using Bu–Zhong–Yi–Qi–Tang (%) | aORb (95 % CIc) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | 685 (77.1) | 204 (22.9) | |

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| <45 | 5 (0.7) | 2 (1) | 0.69 (0.12–6.03) |

| 45–54 | 21 (3.1) | 2 (1) | 3.17 (0.70–17.44) |

| 55–64 | 88 (12.8) | 22 (10.8) | 1 |

| 65–74 | 221 (32.1) | 70 (34.3) | 0.72 (0.23–1.34) |

| 75–84 | 304 (44.1) | 92 (45.1) | 0.92 (0.41–1.52) |

| ≥85 | 45 (6.5) | 16 (7.8) | 0.64 (0.22–1.59) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 377 (55.0) | 99 (48.5) | 1.23 (1.04–1.57) |

| Male | 308 (45.0) | 104 (51.0) | 1 |

| Numbers of anti–Alzheimer’s or BPSD drugs | |||

| 1 | 26 (3.8) | 11 (5.4) | 1 |

| 2 | 133 (19.4) | 55 (27.0) | 0.82 (0.21–2.01) |

| 3 | 259 (37.8) | 75 (36.8) | 1.32 (0.52–2.81) |

| ≥4 | 367 (39.0) | 63 (40.9) | 1.04 (0.57–2.11) |

| Numbers of dementia BPSDd | |||

| 0 | 84 (12.3) | 42 (20.6) | 1 |

| 1 | 115 (16.8) | 63 (30.9) | 0.72 (0.31–1.68) |

| 2 | 206 (30.1) | 52 (25.5) | 2.11 (0.93–3.38) |

| ≥3 | 280 (40.9) | 63 (30.9) | 2.75 (0.82–4.31) |

| Numbers of comorbidity | |||

| 0 | 22 (3.2) | 12 (5.9) | 1 |

| 1 | 90 (13.1) | 35 (17.2) | 1.21 (0.38–3.71) |

| 2 | 119 (17.4) | 57 (27.9) | 1.02 (0.31–4.23) |

| ≥3 | 454 (66.3) | 99 (48.5) | 2.24 (0.71–4.55) |

a CM refers to traditional Chinese medicine

b aOR refers to adjust odds ratio

c CI refers to confidence interval

d BPSD refers to behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first reported one using a random national-level sample to document the usage characteristics of traditional Chinese medicines in AD patients. The incidence of AD was less than 0.3 % in people aged 55–64 years, with the incidence increasing with increasing age. In people aged 85 years or older, the incidence was found to be 17.9 %, which is low compared with results of previous surveys [10, 11]. Notably, all of the patients described in the current study were newly diagnosed with AD by board-certified neurologists or psychiatrists and selected from a random sample of one million patients. Furthermore, these patients were selected from the insured general population of Taiwan and the rate of insured people was consistently above 97 % since 1997. The possibility of selection or recall bias could therefore be excluded.

More than 78 % of the AD patients in the cohort were used some form of CM during the 12 years covered by the current study. High accessibility and full coverage for CM through the NHI scheme in Taiwan could lead to an increase in CM use. Furthermore, several Chinese herbs may be effective as alternative therapies for treating AD and related disorders [12]. The current findings also show that women and those living in urban areas are more likely to use CM than men and patients living rural areas. Similar trends were reported previously [13].

BPSD relating to AD such as delusions, paranoia, hallucinations and anxiety could lead to an increase in caregiver burden and accelerate the progression of AD [14]. AD patients suffering from one or more BPSD were more likely to use traditional CM than those with no BPSD. In addition, using anti-AD or BPSD drugs did not lead to a reduction in CM use. AD patients consumed herbal therapies with the aim of relieving their AD-related symptoms, rather than using these treatments as alternatives to standard anti-AD treatments (i.e., herbal therapies were consumed as complementary medicines).

The category “symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions” was the most frequently cited diagnosis in the disease category for CM visits to classify the diagnosis pattern of CM. This phenomenon has also been observed in several other patient populations [15]. In addition, 9.3 % of patients with AD in the “mental disorders, diseases of the nervous system and sense organs” disease category had specifically sought out CM to treat their condition. CM treatments were generally used as adjuvant therapies to relieve AD-related symptoms rather than being used as replacements for conventional anti-AD treatment.

The category “diseases of the digestive system” was cited as one of the most common reasons for using CHPs (11.9 %, 2954 visits), with Ma-Zi-Ren-Wan being used to treat constipation [16]. Constipation is a common problem among geriatric patients, especially those with AD, in whom it is generally exacerbated by a lack of exercise or the side effects of anti-AD drugs [17]. Severe constipation in AD patients can lead to confusion and symptoms of irritability or aggression because of the pain and discomfort associated with this condition [18]. Moreover, emodin, which is the major chemical constituent of Ma-Zi-Ren-Wan, protects the cortical neurons from β-amyloid-induced toxicity, representing a possible mechanism for treating AD [19]. In this study, Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang was determined to be the most commonly prescribed formula, especially for female AD patients. Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang led to elevated levels of dopamine and noradrenaline in the cortical tissues of mice, as well as improved attention, learning function and memory [20, 21]. Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang was also used to treat elderly patients with weakness and fatigue [22].

Some frequently prescribed formulae have been reported to exhibit potentially positive effects on AD. For example, Sheng-Mai-San was reported to improve memory and decrease neuronal apoptosis in the hippocampus [23]. Furthermore, Ji-Sheng-Shen-Qi-Wan and Liu-Wei-Di-Huang-Wan, which both belong to the Di-Huang-Wan group of formulae and share similar herbal components, were reported to increase cognitive function after 2 months of treatment [24]. Some formulae were reported to show neuroprotective activity. For example, Tian-Ma-Gou-Teng-Yin led to a reduction in necrosis and apoptosis in neuronal cells through a variety of pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidative and antiapoptotic activities [25]. Tao-Hong-Si-Wu-Tang exhibited neuroprotective effects against focal cerebral ischemia. Moreover, Gan-Mai-Da-Zao-Tang exhibited sedative and anti-anxiety effects in an animal model [26]. All of the aforementioned formulae, which are standard formulae recommended by the DCMP, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan, must be modified by qualified CM practitioners in accordance with the principle of syndrome pattern identification as the basis for determining treatment.

Table 4 lists all of the herbs contained in the top ten most frequently prescribed formulae. Ginseng Radix (Ren-Shen), which is the major constituent herb in three of the top ten formulae, has been reported to show multiple effects against AD-related factors such as decreasing β-amyloid formation [27], increasing choline acetyltransferase [28] and forming a competitive interaction with the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor [29]. Ginseng Radix has also been reported to increase cognitive function [30]. Angelicae Sinensis Radix Integra (Dang-Gui) is the key component of Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang, Tian-Wang-Bu-Xin-Dan and Tao-Hong-Si-Wu-Tang. An ethanolic extract of Dang-Gui enhanced cholinergic function [31], inhibited acetylcholinesterase [32], reduced β-amyloid associated neurotoxicity and decreased Tau protein hyperphosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner [33].

There were several limitations associated with the current study. First, health foods containing herbs, folk medicines and prescriptions from CM practitioners without a license from the Taiwanese authorities were not included in this study. Therefore CHP use may have therefore been underestimated. However, high healthcare insurance coverage and low prices of government-approved CM led to a reduction in herbal folk medicine use. Second, it is not possible to draw any conclusions regarding the relationship between cognitive function and CM use because of a general lack of detailed clinical data. This study focused primarily on a patient population with AD, the AD diagnosis was rigorously censored by the Bureau of National Health Insurance. Third, this study was conducted retrospectively and did not include a randomized placebo group. Lastly, the CM formulae were modified according to the principle of syndrome differentiation.

Conclusions

Most people with AD who consumed herbal products used supplement qi, nourish the blood, and quiet the heart spirit therapy as complementary medicines to relieve AD-related symptoms, in addition to using standard anti-AD treatments.

Authors’ contributions

SKL, SHY, and JNL designed the study. SKL and JNL acquired the data. SKL analyzed the data. SKL, SHY, and THT wrote the manuscript. SKL, SHY, and THT revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted at the Institute of Traditional Medicine at the School of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taiwan. The authors would like to express sincere gratitude for the partial support provided for this project in the form of grants from the Department of Health, Taipei City Government 102XDAA00111), the Department of Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy (CCMP-102-CMB-7), and the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC 99-2320-B-010-011-MY2). We would like to thank language editor Mrs. Judy Wu for professional assistance.

Competing interests

The sponsors of the study did not participate in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. All data was collected from the National Health Research Database. All authors had financial support from the Department of Health, Taipei City Government (Taiwan), the Department of Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy, and the National Science Council (Taiwan) for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 5 years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- CM

Chinese medicine

- CHPs

Chinese herbal products

- BPSD

behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia

- NHIRD

National Health Insurance Research Database

- NHI

National Health Insurance

- ICD-9-CM

international classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification

- NINCDS-ADRDA

National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association

- DSM IV

diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

- DCMP

Department of Chinese medicine and pharmacy

- GMP

good manufacturing practice

- MMSE

mini-mental state examination

Additional files

10.1186/s13020-016-0086-9 The approval Letter from Taipei City Hospital Institutional Review Board.

10.1186/s13020-016-0086-9 The approval Letter from National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Shun-Ku Lin, Email: gigilaskl@gmail.com.

Sui-Hing Yan, Email: DAK02@tpech.gov.tw.

Jung-Nien Lai, Email: jnlaitpee@gmail.com.

Tung-Hu Tsai, Email: thtsai@ym.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Ballard C, Gauthier S, Corbett A, Brayne C, Aarsland D, Jones E. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2011;377:1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markowitsch HJ, Staniloiu A. Amnesic disorders. Lancet. 2012;380:1429–1431. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McShane R, Areosa Sastre A, Minakaran N. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD003154. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Yan H, Li L, Tang XC. Treating senile dementia with traditional Chinese medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006;3:441–445. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stange R, Amhof R, Moebus S. Complementary and alternative medicine: attitudes and patterns of use by German physicians in a national survey. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:1255–1261. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsieh SC, Lai JN, Lee CF, Hu FC, Tseng WL, Wang JD. The prescribing of Chinese herbal products in Taiwan: a cross-sectional analysis of the national health insurance reimbursement database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:609–619. doi: 10.1002/pds.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang LC, Huang N, Chou YJ, Lee CH, Kao FY, Huang YT. Utilization patterns of Chinese medicine and Western medicine under the National Health Insurance Program in Taiwan, a population-based study from 1997 to 2003. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:170–177. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin SK, Tsai YT, Lai JN, Wu CT. Demographic and medication characteristics of traditional Chinese medicine users among dementia patients in Taiwan: a nationwide database study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;161:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen FP, Chen TJ, Kung YY, Chen YC, Chou LF, Chen FJ, Hwang SJ. Use frequency of traditional Chinese medicine in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;23:26–34. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu CK, Lai CL, Tai CT, Lin RT, Yen YY, Howng SL. Incidence and subtypes of dementia in southern Taiwan: impact of socio-demographic factors. Neurology. 1998;50:1572–1579. doi: 10.1212/WNL.50.6.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang MI, Katzman R, Yu E, Liu W, Xiao SF, Yan H. A preliminary analysis of incidence of dementia in Shanghai, China. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;52:291–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb03248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dos Santos-Neto LL, de Vilhena Toledo MA, Medeiros-Souza P, de Souza GA. The use of herbal medicine in Alzheimer’s disease—a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006;3:441–445. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang CH, Tsai YT, Lai JN, Hsu FL. Prescription pattern of Chinese herbal products for diabetes mellitus in Taiwan: a population-based study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:201329. doi: 10.1155/2013/201329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Bookwala J, Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: prevalence, correlates, and causes. Gerontologist. 1995;35:771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai JN, Wu CT, Wang JD. Prescription pattern of Chinese herbal products for breast cancer in Taiwan: a population-based study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:891893. doi: 10.1155/2012/891893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jong MS, Hwang SJ, Chen YC, Chen TJ, Chen FJ, Chen FP. Prescriptions of Chinese herbal medicine for constipation under the national health insurance in Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc. 2010;73:375–383. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(10)70081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henley DB, Sundell KL, Sethuraman G, Siemers ER. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative: safety profile of Alzheimer’s disease populations in Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative and other 18-month studies. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allan L, McKeith I, Ballard C, Kenny RA. The prevalence of autonomic symptoms in dementia and their association with physical activity, activities of daily living and quality of life. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22:230–237. doi: 10.1159/000094971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu T, Jin H, Sun QR, Xu JH, Hu HT. Neuroprotective effects of emodin in rat cortical neurons against beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 2010;1347:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih HC, Chang KH, Chen FL, Chen CM, Chen SC, Lin YT, Shibuya A. Anti-aging effects of the traditional Chinese medicine Bu-zhong-yi-qi-tang in mice. Am J Chin Med. 2000;28:77–86. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X00000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura M, Sasada T, Kanai M, Kawai Y, Yoshida Y, Hayashi E, Iwata S, Takabayashi A. Preventive effect of a traditional herbal medicine, Hochu-ekki-to, on immunosuppression induced by surgical stress. Surg Today. 2000;38:316–322. doi: 10.1007/s00595-007-3631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toshiaki K, Nobuhiko S, Eiichi T, Shinya S, Yutaka S, Hiroshi O, Hideki O, Katsutoshi T. Assessment of effects of traditional herbal medicines on elderly patients with weakness using a self-controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2004;4:169–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2004.00246.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Y, Wen YL, Du L. Effect of Shengmaisan on learning and memory abilities and hippocampal nitric oxide synthase expression and neuronal apoptosis in rats with vascular dementia. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2010;30:1327–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwasaki K, Kobayashi S, Chimura Y, Taguchi M, Inoue K, Cho S, Akiba T, Arai H, Cyong JC, Sasaki H. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of the Chinese herbal medicine “ba wei di huang wan” in the treatment of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1518–1521. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chik SC, Or TC, Luo D, Yang CL, Lau AS. Pharmacological effects of active compounds on neurodegenerative disease with gastrodia and uncariadecoction, a commonly used poststroke decoction. Sci World J. 2013;14:896873. doi: 10.1155/2013/896873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen HC, Hsieh MT, Lai E. Studies on the suanzaorentang in the treatment of anxiety. Psychopharmacology. 1985;85:486–487. doi: 10.1007/BF00429670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song XY, Hu JF, Chu SF, Zhang Z, Xu S, Yuan YH, Han N, Liu Y, Niu F, He X, Chen NH. Ginsenoside Rg1 attenuates okadaic acid induced spatial memory impairment by the GSK3β/tau signaling pathway and the Aβ formation prevention in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;710:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi S, Shi R, Hashizume K. American ginseng improves neurocognitive function in senescence-accelerated mice: possible role of the upregulated insulin and choline acetyltransferase gene expression. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12:123–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim S, Kim T, Ahn K, Park WK, Nah SY, Rhim H. Ginsenoside Rg3 antagonizes NMDA receptors through a glycine modulatory site in rat cultured hippocampal neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:416–424. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heo JH, Lee ST, Chu K, Oh MJ, Park HJ, Shim JY, Kim M. An open-label trial of Korean red ginseng as an adjuvant treatment for cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:865–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng LL, Chen XN, Wang Y, Yu L, Kuang X, Wang LL, Yang W, Du JR. Z-ligustilide isolated from radix Angelicae sinensis ameliorates the memory impairment induced by scopolamine in mice. Fitoterapia. 2011;82:1128–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park SJ, Jung JM, Lee HE, Lee YW, Kim DH, Kim JM, Hong JG, Lee CH, Jung IH, Cho YB, Jang DS, Ryu JH. The memory ameliorating effects of INM-176, an ethanolic extract of Angelica gigas, against scopolamine- or Aβ(1-42) - induced cognitive dysfunction in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;143:611–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang ZI, Zhao R, Qi J, Wen S, Tang Y, Wang D. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β by Angelica sinensis extract decreases β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity and tau phosphorylation in cultured cortical neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:437–447. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]