ABSTRACT

The human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) gene UL111A encodes cytomegalovirus-encoded human interleukin-10 (cmvIL-10), a homolog of the potent immunomodulatory cytokine human interleukin 10 (hIL-10). This viral homolog exhibits a range of immunomodulatory functions, including suppression of proinflammatory cytokine production and dendritic cell (DC) maturation, as well as inhibition of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II. Here, we present data showing that cmvIL-10 upregulates hIL-10, and we identify CD14+ monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages and DCs as major sources of hIL-10 secretion in response to cmvIL-10. Monocyte activation was not a prerequisite for cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10, which was dose dependent and controlled at the transcriptional level. Furthermore, cmvIL-10 upregulated expression of tumor progression locus 2 (TPL2), which is a regulator of the positive hIL-10 feedback loop, whereas expression of a negative regulator of the hIL-10 feedback loop, dual-specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1), remained unchanged. Engagement of the hIL-10 receptor (hIL-10R) by cmvIL-10 led to upregulation of heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), an enzyme linked with suppression of inflammatory responses, and this upregulation was required for cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10. We also demonstrate an important role for both phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and STAT3 in the upregulation of HO-1 and hIL-10 by cmvIL-10. In addition to upregulating hIL-10, cmvIL-10 could exert a direct immunomodulatory function, as demonstrated by its capacity to upregulate expression of cell surface CD163 when hIL-10 was neutralized. This study identifies a mechanistic basis for cmvIL-10 function, including the capacity of this viral cytokine to potentially amplify its immunosuppressive impact by upregulating hIL-10 expression.

IMPORTANCE Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a large, double-stranded DNA virus that causes significant human disease, particularly in the congenital setting and in solid-organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. A prominent feature of HCMV is the wide range of viral gene products that it encodes which function to modulate host defenses. One of these is cmvIL-10, which is a homolog of the potent immunomodulatory cytokine human interleukin 10 (hIL-10). In this study, we report that, in addition to exerting a direct biological impact, cmvIL-10 upregulates the expression of hIL-10 by primary blood-derived monocytes and that it does so by modulating existing cellular pathways. This capacity of cmvIL-10 to upregulate hIL-10 represents a mechanism by which HCMV may amplify its immunomodulatory impact during infection.

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a species-specific betaherpesvirus that infects a majority of the world's population (1). In immunocompetent individuals, productive HCMV infection is mostly asymptomatic and is eventually controlled by the host immune response, yet the virus is never completely cleared. Instead, HCMV establishes a lifelong latent infection in cells of the myeloid lineage, from where it can later reactivate to produce new, infectious virus (2–6). The outcome of infection in immunosuppressed or immuno-naïve individuals differs from infection in those who are immunocompetent, with primary productive infection or reactivated infection being associated with significant morbidity and mortality in neonates, in those with HIV AIDS, and in solid-organ and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients (1).

The capacity of HCMV to successfully infect the host and cause disease is likely to be at least partially attributable to a diverse range of HCMV genes which encode proteins with immunomodulatory functions (1). One group of HCMV immunomodulatory genes has acquired the capacity to mimic cellular cytokines, chemokines, or their receptors, including two homologs of the potent immunomodulatory cytokine human interleukin 10 (hIL-10), cytomegalovirus-encoded hIL-10, termed cmvIL-10, and latency-associated cmvIL-10 (LAcmvIL-10) (7, 8).

The expression of cmvIL-10 from the UL111A gene during productive HCMV infection was identified by two groups (9, 10). Despite sharing only 27% homology with hIL-10 amino acid sequence, cmvIL-10 retains the capacity to bind and signal through the hIL-10 receptor (hIL-10R) (11, 12). As a result, cmvIL-10 appears to share the same immunomodulatory functions as hIL-10, including suppression of proinflammatory cytokines (13), modulation of dendritic cell (DC) functions (14–18), suppression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II expression (13, 19), and stimulation of B lymphocytes (12). LAcmvIL-10 is a truncated version of cmvIL-10 (20), and its biological functions appear to be more restricted than those of cmvIL-10. For example, LAcmvIL-10 has been shown to suppress MHC class II expression (19), but, unlike cmvIL-10, it does not appear to suppress proinflammatory cytokine production or DC maturation or to stimulate B cells (12, 19).

Several studies have investigated the combined effects of cmvIL-10 and LAcmvIL-10 utilizing UL111A deletion viruses (that ablate expression of both cmvIL-10 and LAcmvIL-10). These studies identified a role for UL111A in suppression of MHC class II expression in latently infected cells, with subsequent protection from CD4+ T cell recognition, as well as impairment of differentiation of latently infected myeloid progenitor cells to DCs (21, 22). In addition, treatment of CD14+ monocytes with either a mixture of recombinant cmvIL-10 and LAcmvIL-10 proteins (termed viral IL-10) or with supernatants from permissive human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) infected with parental or UL111A deletion viruses has demonstrated that the UL111A gene products skew monocyte polarization toward a deactivated M2c phenotype that significantly reduces CD4+ T cell activation and proliferation (23). Interestingly, LAcmvIL-10 increases hIL-10 secretion by CD14+ monocytes, suggesting that this viral cytokine may amplify its biological impact via modulation of hIL-10 (24). In addition, there have been sporadic reports that cmvIL-10 also upregulates secretion of hIL-10 (12, 16, 25), but the cellular sources of hIL-10 and the mechanisms of cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10 secretion have not been defined.

In the present study, we demonstrate that cmvIL-10 potently induces hIL-10 mRNA transcription and protein secretion in human primary monocytes and monocyte-derived cells, thus providing additional means to amplify the immunomodulatory functions of cmvIL-10. The upregulation of hIL-10 by cmvIL-10 was dose and time dependent, but we also show that cmvIL-10 is capable of exerting a direct biological impact in the absence of functional hIL-10. Finally, we demonstrate that the induction of hIL-10 by cmvIL-10 is dependent on the induction of heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) via signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant proteins and neutralizing antibodies.

Recombinant cmvIL-10 and hIL-10 proteins (R&D Systems) were used at a variety of concentrations. Mo-DC differentiation medium (Mo-DC Generation Toolbox I; Miltenyi Biotech) containing recombinant human IL-4 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) was used as per the manufacturer's instructions. Purified rat anti-human IL-10 antibody (BD Pharmingen) was used at 2 μg/ml to neutralize hIL-10 protein. Human IL-10 receptor alpha neutralizing monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems) was used at 25 μg/ml. The isotype control for neutralization experiments was purified rat IgG2a antibody R35-95 (BD Pharmingen).

Cells.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were derived from whole blood by Ficoll-Hypaque Plus (GE Healthcare) gradient centrifugation. Blood was obtained from the Australian Red Cross Blood Bank with Institutional Review Board Approval by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee. Primary human CD14+ monocytes were isolated from PBMCs by positive selection with anti-human CD14 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) and maintained at 7.5 × 105 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium (Lonza) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; CSL). Monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) were generated by culturing CD14+ monocytes at 7.5 × 105 cells/ml in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium for 2 h to allow monocyte adherence, followed by culturing in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% human AB serum (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 days. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MDDCs) were generated by culturing CD14+ monocytes at 7.5 × 105 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and Mo-DC differentiation medium for 5 days. Human primary CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and CD19+ B lymphocytes were isolated from PBMCs by positive selection with anti-human CD4, CD8, and CD19 magnetic beads, respectively (Miltenyi Biotec), and maintained at 1 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS. The purity for all cell types isolated with magnetic beads was >90%. Human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Lonza) supplemented with 10% FCS.

Treatment of CD14+ monocytes with zinc and cobalt protoporphyrins.

CD14+ monocytes were pulsed for 2 h with the HO-1 inhibitor zinc protoporphyrin (ZnPP, 10 nmol/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) or the HO-1 inducer cobalt protoporphyrin (CoPP, 10 nmol/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) prior to administration of recombinant cmvIL-10 protein (100 ng/ml) for 24 h.

PI3K and STAT3 inhibition in cmvIL-10-stimulated CD14+ monocytes.

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor LY-294002 and STAT3 inhibitor VI (S3I-201) (Sigma-Aldrich) were resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich). CD14+ monocytes were pulsed for 4 h with PI3K inhibitor (50 μM), STAT3 inhibitor (50 μM), or an equivalent volume of DMSO (control) prior to administration of recombinant cmvIL-10 protein (1 ng/ml) for 18 h.

ELISA.

A human IL-10 Quantikine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems) was used as per the manufacturer's protocol. Absorbance was measured by a FLUOstar Omega reader (BMG Labtech) at 450 nm with wavelength correction set at 540 nm.

qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from CD14+ monocytes using an innuPREP RNA minikit (Analytik-Jena) prior to cDNA synthesis using an AffinityScript cDNA synthesis kit (Agilent Technologies). Reaction mixtures were set up using Brilliant II SYBR Green quantitative PCR (QPCR) master mix (Agilent Technologies), and changes in mRNA expression levels were measured by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) (StepOne Plus; Applied Biosystems) as per a previously published protocol (23). The following primers were used in this study: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase forward primer (GAPDH-F), 5′-TCACCAGGGCTGCTTTTAAC-3′; GAPDH reverse (GAPDH-R), 5′-GACAAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAG-3′; hIL-10-F, 5′-GCCTAACATGCTTCGAGATC-3′; hIL-10-R, 5′-TGATGTCTGGGTCTTGGTTC-3′; dual-specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1)-F, 5′-CTGCCTTGATCAACGTCTCA-3′; DUSP1-R, 5′-ACCCTTCCTCCAGCATTCTT-3′; tumor progression locus 2 (TPL2)-F, 5′-TTCCGATGTTCTCCTGATCC-3′; TPL2-R, 5′-CAGTTTCACCCCACAGGACT-3′.

Immunostaining and flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry for cell surface proteins was performed as per a previously published protocol (23). Antibodies used in this study were mouse anti-human CD163-phycoerythrin (PE) (BD Biosciences) with a corresponding isotype control. In addition, samples for intracellular flow cytometry were prepared using a Cytofix/Cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization Solution kit (BD Biosciences) as per the manufacturer's protocol with the following antibodies: mouse anti-human HO-1–PE (Abcam) and mouse anti-human GAPDH-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (EMD Millipore) with corresponding isotype controls.

RESULTS

cmvIL-10 upregulates secretion of hIL-10 protein by CD14+ monocytes and monocyte-derived cells.

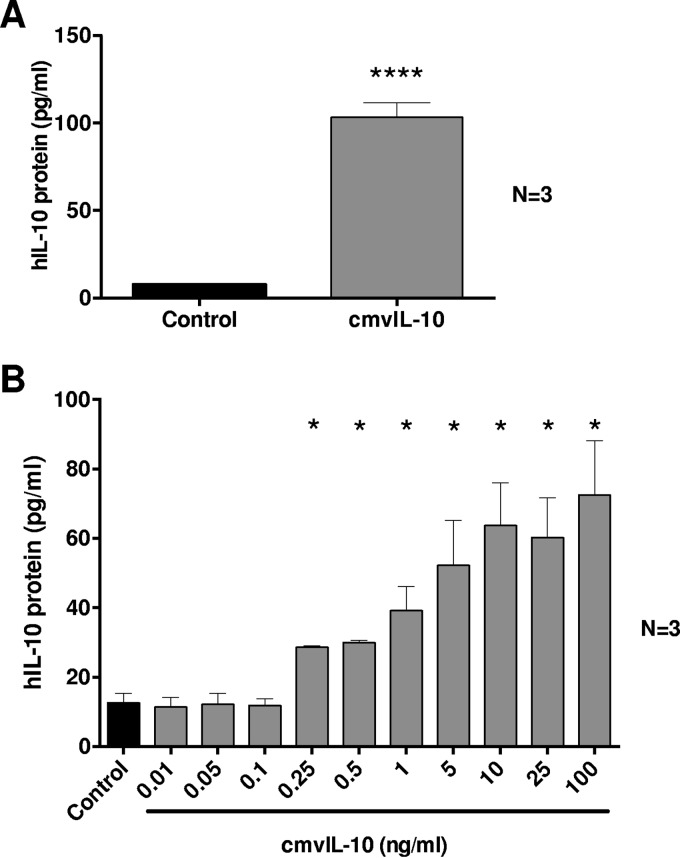

Secretion of cmvIL-10 from cells infected with HCMV may influence the hIL-10 production capacity of bystander cells. Thus, to investigate the impact of cmvIL-10 on hIL-10 secretion, we treated freshly isolated primary human CD14+ monocytes with cmvIL-10 protein (100 ng/ml for 24 h) or control diluent and measured secreted hIL-10 by ELISA. This treatment resulted in a strong upregulation of hIL-10 protein secretion (Fig. 1A). The impact of cmvIL-10 on hIL-10 secretion by CD14+ monocytes was dose dependent, with as little as 250 pg/ml of cmvIL-10 protein causing a significant upregulation of hIL-10 (Fig. 1B). To exclude the possibility of hIL-10 ELISA detecting cmvIL-10, we demonstrated the absence of cross-reactivity by adding 100 ng/ml of recombinant cmvIL-10 protein to ELISA wells, which resulted in absorbance readings equivalent to background readings seen in negative controls (data not shown).

FIG 1.

Human CD14+ monocytes exhibit increased hIL-10 protein secretion in response to cmvIL-10. (A) ELISA-based quantitation of hIL-10 in the supernatants of cultures of primary human peripheral blood-derived CD14+ monocytes treated for 24 h with cmvIL-10 (100 ng/ml) or with phosphate-buffered saline (control). (B) Dose-dependent upregulation of hIL-10 secretion by CD14+ monocytes cultured with increasing concentrations of cmvIL-10 or with phosphate-buffered saline (control). The number (N) of independent biological replicate experiments is shown. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. Significant differences between results for the test samples and those of the control were determined using a two-tailed, paired Student's t test and are denoted by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; ****, P < 0.0001).

To determine whether cmvIL-10 exerted a similar impact on hIL-10 secretion by other immune cell types, we treated blood-derived monocyte derived-macrophages (MDMs), monocyte-derived immature dendritic cells (MDDCs), CD19+ B cells, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with cmvIL-10 or a control. We also examined primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs), which is a cell type permissive to productive HCMV replication that has also been shown to play an important role in regulating a variety of immune functions (26–28). In three independent replicate experiments, both MDMs and MDDCs significantly upregulated hIL-10 in response to cmvIL-10 treatment, whereas hIL-10 remained below detectable limits before and after cmvIL-10 treatment of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and HFFs. CD19+ B cells displayed a modest, but not statistically significant, increase in hIL-10 secretion (Table 1). These data demonstrated that myeloid cells (human primary CD14+ monocytes, MDMs, and MDDCs) were a prominent cell lineage that responded to cmvIL-10 by upregulating secretion of hIL-10.

TABLE 1.

Quantification of secreted hIL-10 protein by ELISA following exposure of different cell types to cmvIL-10

| Cell typea | Amt (pg/ml) of hIL-10 in cells treated with:b |

|

|---|---|---|

| Control | cmvIL-10 | |

| MDMs | 40.31 | 83.26*** |

| MDDCs | 22.20 | 112.12* |

| CD19+ B cells | 6.91 | 9.34 |

| CD8+ T cells | ND | ND |

| CD4+ T cells | ND | ND |

| HFFs | ND | ND |

MDMs, monocyte-derived macrophages; MDDCs, monocyte-derived dendritic cells; HFFs, human foreskin fibroblasts.

Values represent results from three replicate experiments. ND, not detected. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

cmvIL-10 does not require hIL-10 for its biological activity.

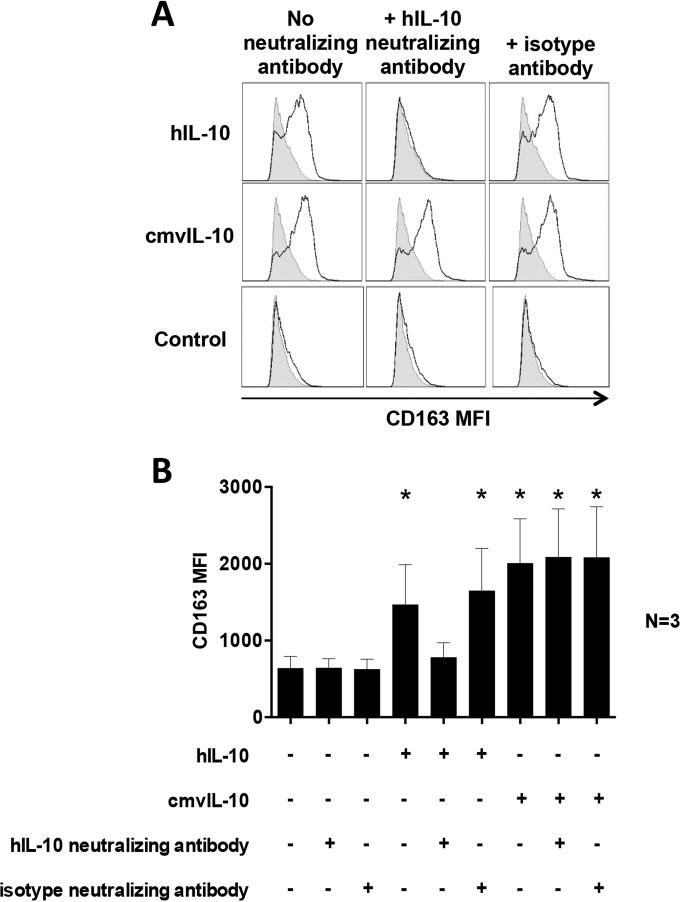

We along with others have established a range of impacts of cmvIL-10 on immune functions by myeloid cells (8, 12–16, 18, 19, 25, 29). Thus, the finding that cmvIL-10 upregulates hIL-10 secretion raises the important issue as to whether cmvIL-10 is dependent upon upregulation of hIL-10 to exert a biological impact or whether cmvIL-10 can function directly, without hIL-10. To address these possibilities, we preincubated CD14+ monocytes with a neutralizing antibody against hIL-10 for 2 h before addition of cmvIL-10 for 24 h and then assessed cell surface expression of CD163, which we have previously reported to be potently induced by hIL-10 and HCMV viral IL-10 (23). This analysis revealed that hIL-10 strongly upregulated cell surface CD163 on CD14+ monocytes, but this upregulation was abolished in the presence of hIL-10 neutralizing antibody (Fig. 2A). In contrast, cmvIL-10 was capable of strongly upregulating CD163 even in the presence of hIL-10 neutralizing antibody (Fig. 2A). The capacity of cmvIL-10, but not hIL-10, to upregulate CD163 in the presence of hIL-10 neutralizing antibody was observed consistently in three independent biological replicates (Fig. 2B). Collectively, these data demonstrate that, in addition to upregulating hIL-10, cmvIL-10 is also capable of directly exerting an immunomodulatory effect in the absence of functional hIL-10.

FIG 2.

cmvIL-10 is biologically active in the absence of hIL-10. (A) Flow cytometry-based assessment of cell surface CD163 by CD14+ monocytes pretreated with hIL-10 neutralizing antibody or its isotype control antibody for 2 h prior to incubation for 24 h with cmvIL-10, hIL-10, or phosphate-buffered saline (Control). Open histograms depict CD163 after staining with a CD163-specific antibody, and filled histograms depict CD163 expression after staining with an isotype control antibody. (B) Graph depicting the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of cell surface CD163 by CD14+ monocytes pretreated with hIL-10 neutralizing antibody or isotype control antibody followed by hIL-10 or cmvIL-10 treatment. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means from three independent biological replicate experiments. Significant differences between results for the test samples and those with the control were determined using a two-tailed, paired Student's t test and are denoted by asterisks (*, P < 0.05).

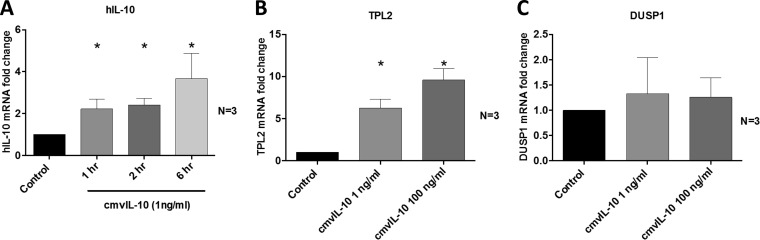

cmvIL-10 upregulates mRNA expression of hIL-10 and its positive regulator TPL2.

To determine whether cmvIL-10 upregulates hIL-10 at the level of transcription, levels of hIL-10 mRNA were measured by qRT-PCR over time in CD14+ monocytes following treatment with cmvIL-10. Induction of hIL-10 by cmvIL-10 was regulated at the transcript level, as indicated by a significant increase in hIL-10 mRNA expression following exposure of cmvIL-10 to CD14+ monocytes (Fig. 3A). We also examined the mRNA expression of tumor progression locus 2 (TPL2) and dual-specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1), which act as regulators of positive and negative feedback loops for hIL-10 production, respectively (30). As shown in Fig. 3B, CD14+ monocytes responded to cmvIL-10 by upregulating TPL2, while expression of DUSP1 remained unchanged (Fig. 3C). These data demonstrate that cmvIL-10 acts to upregulate transcription of hIL-10 as well as the positive regulator of hIL-10, TPL2, but does not significantly alter expression of the negative hIL-10 regulator DUSP1.

FIG 3.

cmvIL-10 upregulates transcription of hIL-10 and TPL2 but not DUSP1. CD14+ monocytes were treated with cmvIL-10 or with phosphate-buffered saline (Control), and qRT-PCR was used to quantify the fold change in mRNA expression of hIL-10, TPL2, and DUSP1, determined relative to the levels with treatment with phosphate-buffered saline (Control). The number (N) of independent biological replicate experiments is shown. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. Significant differences between results for the test samples and those of the control were determined using a two-tailed, paired Student's t test and are denoted by asterisks (*, P < 0.05).

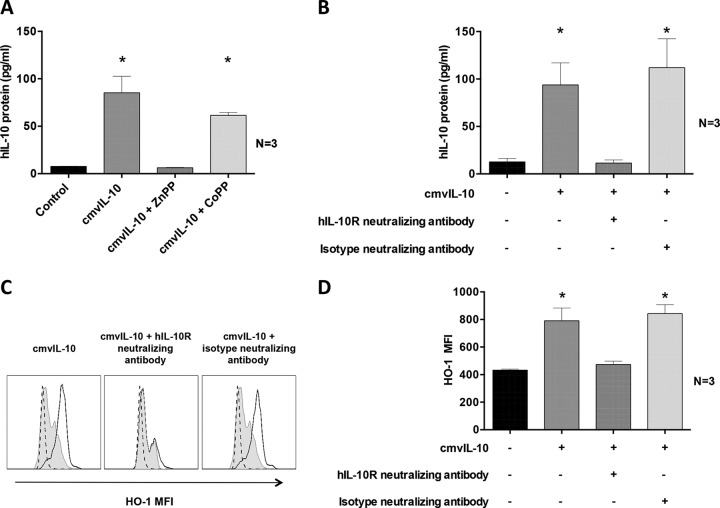

Heme oxygenase 1 expression is associated with cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10 secretion.

We previously reported that heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), an enzyme associated with suppression of inflammatory responses (31), is induced by HCMV viral IL-10 (23). We along with others have also reported that cmvIL-10 exerts its biological functions by binding and signaling through the hIL-10 receptor (hIL-10R) (9, 11, 12, 19). In the present study, we sought to determine whether cmvIL-10 utilizes HO-1 and hIL-10R to upregulate hIL-10 secretion by CD14+ monocytes. Monocytes were cultured with the HO-1 competitive inhibitor ZnPP or with the HO-1 inducer CoPP for 2 h prior to exposure to cmvIL-10, and then supernatants were assessed by ELISA for secreted hIL-10. While inhibition of HO-1 by ZnPP strongly impaired hIL-10 secretion by CD14+ monocytes treated with cmvIL-10, hIL-10 secretion by CD14+ monocytes treated with CoPP continued to be strongly upregulated by cmvIL-10 (Fig. 4A). To further investigate the role of HO-1 in cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10 secretion, we utilized a hIL-10R neutralizing antibody to block cmvIL-10 binding to hIL-10R and then measured hIL-10 and HO-1 protein expression in response to treatment with cmvIL-10. An isotype control antibody was included to confirm the specificity of the IL-10R neutralizing antibody. This analysis demonstrated that cmvIL-10 was unable to upregulate hIL-10 secretion when hIL-10R was blocked, confirming a role of IL-10R in upregulation of hIL-10 by cmvIL-10 (Fig. 4B). Moreover, upregulation of HO-1, as determined by intracellular flow cytometry, was also prevented in cmvIL-10-treated CD14+ monocytes treated with the hIL-10R neutralizing antibody but not in cmvIL-10-treated CD14+ monocytes treated with the isotype antibody (Fig. 4C and D). These results demonstrate that interaction between cmvIL-10 and IL-10R modulates HO-1 production, leading to hIL-10 secretion.

FIG 4.

cmvIL-10 requires binding to hIL-10R and functional HO-1 for induction of hIL-10 protein secretion. (A) hIL-10 protein secretion determined by ELISA in supernatants from CD14+ monocytes pretreated with the HO-1 inhibitor ZnPP or the HO-1 inducer CoPP for 2 h prior to incubation for 24 h with cmvIL-10 or with phosphate-buffered saline (Control). (B) Graph depicting the amount of secreted hIL-10 determined by ELISA from CD14+ monocyte cultures pretreated with hIL-10R neutralizing antibody or its isotype antibody for 2 h prior to 24 h of treatment with cmvIL-10. (C) Representative flow cytometry histograms showing expression of intracellular HO-1 in CD14+ monocytes pretreated with neutralizing antibody to hIL-10R or its isotype control antibody. Open histograms depict HO-1 expression after treatment with cmvIL-10. Filled histograms depict results with phosphate-buffered saline (Control), and dotted histograms depict results after staining with an isotype control antibody. (D) Graph depicting the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of HO-1 determined by intracellular flow cytometry from CD14+ monocyte cultures pretreated with hIL-10R neutralizing antibody or its isotype antibody The number (N) of independent biological replicate experiments is shown. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. Significant differences between results for the test samples and those with the control were determined using a two-tailed, paired Student's t test and are denoted by asterisks (*, P < 0.05).

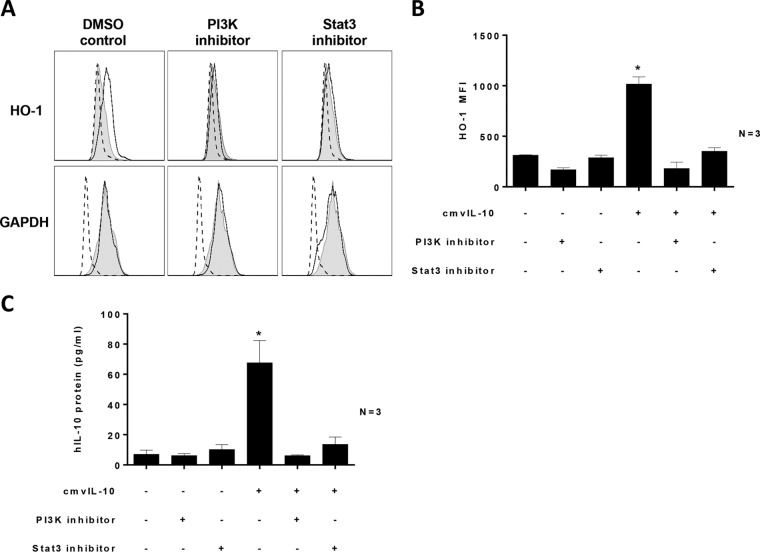

Both PI3K and STAT3 activity are required for cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of HO-1 and hIL-10.

It is well established that hIL-10 activates transcription factor STAT3 (32). However, emerging evidence also highlights the importance of PI3K signaling as a regulator of hIL-10 anti-inflammatory functions (33). Furthermore, cmvIL-10 activates both STAT3 and PI3K signaling (29). Thus, we sought to determine whether PI3K and STAT3 played a role in the cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of HO-1 and hIL-10. CD14+ monocytes were pretreated with inhibitors of PI3K or STAT3 before exposure of cells to cmvIL-10.

Inhibition of both PI3K and STAT3 resulted in inhibition of cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of HO-1 protein expression, as determined by intracellular flow cytometry (Fig. 5A and B). This suppression of HO-1 was not due to global suppression of cellular proteins by these inhibitors, as indicated by consistent levels of GAPDH expression (Fig. 5A), and there was no difference in cell death in monocyte cultures treated with PI3K and STAT3 inhibitors compared to results in control samples (measured by a Zombie live/dead cell stain [BioLegend]) (data not shown). In addition, inactivation of PI3K or STAT3 blocked cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10, as determined by ELISA (Fig. 5C). These data identify an important role for both STAT3 and PI3K in the upregulation of HO-1 and hIL-10 by cmvIL-10 in CD14+ monocytes.

FIG 5.

PI3K and STAT3 are required for cmvIL-10-mediated induction of HO-1 and hIL-10. CD14+ monocytes were pretreated with PI3K inhibitor (LY-294002; 50 μM) and STAT3 inhibitor (S3I-201; 50 μM) or with DMSO (Control) for 4 h prior to incubation for 18 h with cmvIL-10. (A) Histograms showing HO-1 and GAPDH levels by intracellular flow cytometry. Open histograms depict results for samples treated with cmvIL-10, and filled histograms depict results for samples treated with DMSO (Control). Dotted-line histograms depict results for samples treated with an isotype control antibody. (B) Graph depicting the intracellular HO-1 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values in monocyte cultures treated with cmvIL-10, with or without inhibitors, relative to those of the control. (C) Graph depicting the levels of secreted hIL-10 in monocyte cultures treated with cmvIL-10, with or without inhibitors, relative to those of the control. The number (N) of independent biological replicate experiments is shown. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. Significant differences between results for test samples and those with the DMSO control were determined using a two-tailed, paired Student's t test and are denoted by asterisks (*, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Human IL-10 (hIL-10) is a major immunomodulatory cytokine that strongly suppresses proinflammatory cytokines, MHC class I and II expression, and a range of monocyte, macrophage, DC, and T cell functions (32). Since the discovery of cmvIL-10 (9, 10), a number of studies have identified a range of cmvIL-10-mediated immunomodulatory functions that appear to mimic those of hIL-10 (8, 12–14, 16, 18, 19, 29, 32). Here, we report that cmvIL-10 adopts a two-pronged approach to exert its immunomodulatory functions. First, cmvIL-10 can directly modulate host immune gene expression, and, second, cmvIL-10 potently upregulates secretion of hIL-10, thus amplifying its immunomodulatory potential. We also identify the major cell types targeted by cmvIL-10 to upregulate hIL-10, the kinetics of hIL-10 mRNA upregulation, and cellular factors mediating this upregulation.

cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10 protein secretion was most evident from CD14+ monocytes, monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs), and immature monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MDDCs). Although subsets of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have been identified in a range of settings to be capable of secreting hIL-10 (34–37), hIL-10 secretion remained undetectable from these cell types following treatment with cmvIL-10, indicating that they may be incapable of responding to cmvIL-10 in the same manner as myeloid cells or that any upregulation of hIL-10 remained below the limits of detection of the ELISA (3.9 pg/ml). Together with the Spencer group, we previously reported that the human B cell line Daudi can upregulate hIL-10 secretion in response to cmvIL-10 (12), and in the present study we found that primary CD19+ B cells displayed a modest, although not statistically significant, increase in hIL-10 secretion in response to cmvIL-10. Thus, while myeloid cells were the most prominent cell lineage that upregulated hIL-10 in response to cmvIL-10, primary B cells may also represent a cell type that is capable of responding to cmvIL-10 in this manner.

CD14+ monocytes and monocyte-derived cells are known producers of hIL-10 in response to Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling triggered by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (38). Chang and colleagues (16) reported that cmvIL-10 treatment of LPS-activated DCs resulted in increased upregulation of endogenous hIL-10 production compared to levels with LPS treatment alone. However, our results demonstrate that cmvIL-10 upregulates hIL-10 secretion even in the absence of LPS-mediated cell activation. We also show that the treatment of unstimulated CD14+ monocytes with cmvIL-10 results in a time-dependent upregulation of hIL-10 at the transcriptional level, with elevated hIL-10 mRNA observed as early as 1 h posttreatment with cmvIL-10. The timing of this upregulation is comparable to that of the upregulation of hIL-10 transcription by hIL-10 protein (39) and so not only highlights the rapid nature of cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10 mRNA transcription but also suggests that cmvIL-10 may act as a catalyst to drive hIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10. However, while cmvIL-10 may amplify its immunomodulatory impact by upregulating hIL-10, it does not absolutely require hIL-10 to function as cmvIL-10 remained capable of upregulating cell surface CD163, a scavenger receptor expressed at high levels on hIL-10-induced, deactivated M2 monocytes/macrophages (23, 40, 41), even when hIL-10 was neutralized. Thus, cmvIL-10 appears to be capable of functioning both directly and indirectly and in doing so may provide more than one opportunity for HCMV to suppress host immune function(s).

The capacity of hIL-10R neutralizing antibody to completely block upregulation of hIL-10 by cmvIL-10 in CD14+ monocytes suggests that there is an essential requirement for cmvIL-10 to engage the hIL-10R to manifest this phenotype. The capacity of cmvIL-10 to function in this manner is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that cmvIL-10 exerts other functions by binding and signaling through hIL-10R (9, 11, 13, 19). In addition to the engagement of hIL-10R, we show that functional HO-1, a heme-degrading enzyme with immunosuppressive functions (31), is also required for cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10. We previously reported that HO-1 is upregulated in CD14+ monocytes treated with recombinant viral IL-10 protein or by treatment with supernatant from cells infected with parental virus but not by treatment with supernatant from cells infected with a viral IL-10 deletion virus (23). Our current work shows that cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of HO-1 in CD14+ monocytes requires binding of cmvIL-10 to hIL-10R and that this HO-1 upregulation is important for the upregulation of hIL-10.

We also identified signaling pathways utilized by cmvIL-10 to stimulate expression of both HO-1 and hIL-10. Both PI3K and STAT3 were each required for cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10 and HO-1 as blocking either PI3K or STAT3 abolished the capacity of cmvIL-10 to modulate the expression of both hIL-10 and HO-1. In this respect, there is increasing evidence suggesting that both hIL-10 and cmvIL-10 utilize PI3K signaling for a number of their functions (29, 33, 42, 43). In the case of cmvIL-10, the PI3K pathway is essential for suppression of proinflammatory cytokines (29). Interestingly, cmvIL-10-driven PI3K activation also results in phosphorylation of STAT3, suggesting that, in this context at least, the two signaling pathways may be linked (29). Furthermore, the upregulation of HO-1 by hIL-10 also requires both PI3K and STAT3 activity (42). Thus, hIL-10 and cmvIL-10 may simultaneously trigger both the STAT3 and PI3K pathways, which, independent of each other, induce HO-1 and hIL-10; alternatively, the PI3K pathway may converge at some point with the STAT3 pathway to ultimately phosphorylate STAT3 and activate transcription of STAT3-inducible genes. In this respect, PI3K-dependent STAT3 phosphorylation, possibly via activation of Tec family tyrosine kinases, has been reported, and this therefore points toward convergence of the PI3K and STAT3 pathways (44). Given that STAT3 (S727) phosphorylation in cmvIL-10-treated monocytes is PI3K dependent (29) and that STAT3 binding sites are present in the HO-1 gene HMOX1 (45), it is more likely that STAT3 phosphorylation (via PI3K) is the end target of cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10, driven by STAT3 binding to STAT binding sites in HMOX1 promoter, resulting in increased expression of HO-1.

Apart from cmvIL-10, a second homolog of hIL-10, termed latency associated cmvIL-10 (LAcmvIL-10), is also encoded by the HCMV gene UL111A. LAcmvIL-10 is expressed during both latent and productive phases of HCMV infection (20, 46) but appears to exert only a subset of the immunomodulatory functions of cmvIL-10 (8, 12, 19). In the context of upregulation of hIL-10, it has been shown that LAcmvIL-10 is responsible, at least in part, for increased secretion of hIL-10 by latently infected myeloid cells and that the capacity of LAcmvIL-10 to upregulate hIL-10 is mediated by a decrease in the level of the cellular microRNA hsa-miRNA-92a (24, 47, 48). While these studies did not explore the impact of cmvIL-10 on hIL-10 and while our current study did not determine whether LAcmvIL-10 shares the same mechanism to upregulate hIL-10 as reported here, cmvIL-10 and LAcmvIL-10 may utilize different mechanisms to modulate hIL-10, given that LAcmvIL-10 does not appear to bind and signal through hIL-10R or to phosphorylate STAT3 (12, 19). Thus, a comparison of the mechanisms by which cmvIL-10 and LAcmvIL-10 modulate hIL-10 expression across a variety of infection and cell type settings, together with functional analyses, will be important components of future studies aimed at fully delineating the means by which HCMV-encoded IL-10 homologs may amplify their immunomodulatory capability.

The serostatus of the healthy blood donors from which we isolated monocytes was not determined, but based upon population studies, approximately 50% of these donors would be expected to be HCMV seropositive. Thus, it is possible that some monocyte cell samples were obtained from HCMV-seropositive donors that may have been producing LAcmvIL-10 from latently infected cells. However, we did not observe any significant difference in the basal hIL-10 expression levels across multiple different blood donors (data not shown). In addition, during natural latent infection, the proportion of mononuclear cells harboring latent HCMV genomes has been shown to be extremely low (0.004 to 0.01%) (49). Taken together, the HCMV serostatus of blood donors did not appear to have any impact on the cmvIL-10-mediated upregulation of hIL-10 observed in the current study.

In the context of productive replication, our results suggest that reactivation of latent HCMV virus in dendritic cells and macrophages may be a source of cmvIL-10-induced hIL-10 secretion as these were the most prominent cell types that upregulated hIL-10 secretion in response to treatment with cmvIL-10 (Table 1). In contrast to these myeloid lineage cells, cmvIL-10 did not induce detectable hIL-10 by HFFs; however, it remains possible that other cell types permissive to HCMV replication, such as epithelial and endothelial cells, may also respond to cmvIL-10 in a similar manner. In addition, although it remains to be determined experimentally, we predict that the effect of cmvIL-10 on hIL-10 secretion is likely to act in both an autocrine and paracrine manner (i.e., affecting both infected cells and uninfected bystander cells), given that cmvIL-10 is secreted during productive infection and that it also requires interaction with the cell surface IL-10 receptor to induce hIL-10 secretion.

In conclusion, we identify both a direct capacity of cmvIL-10 to exert an immunomodulatory effect and an indirect mechanism whereby cmvIL-10 upregulates hIL-10 in myeloid cells. We therefore propose that cmvIL-10 employs a two-pronged approach, utilizing existing cellular pathways to mediate upregulation of hIL-10 in a manner that enhances the capacity of HCMV to modulate the host immune function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant funding awarded to B.S. and A.A and a British Medical Research Council (MRC) Programme Grant to J.S. (G:0701279)

REFERENCES

- 1.Mocarski ES, Shenk T, Griffiths PD, Pass RF. 2013. Cytomegaloviruses, p 1960–2014. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Rancaniello VR, Roizman B (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed, vol 2 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeves MB, MacAry PA, Lehner PJ, Sissons JG, Sinclair JH. 2005. Latency, chromatin remodeling, and reactivation of human cytomegalovirus in the dendritic cells of healthy carriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:4140–4145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408994102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slobedman B, Cao JZ, Avdic S, Webster B, McAllery S, Cheung AK, Tan JC, Abendroth A. 2010. Human cytomegalovirus latent infection and associated viral gene expression. Future Microbiol 5:883–900. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soderberg-Naucler C, Fish KN, Nelson JA. 1997. Reactivation of latent human cytomegalovirus by allogeneic stimulation of blood cells from healthy donors. Cell 91:119–126. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)80014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanier P, Taylor DL, Kitchen AD, Wales N, Tryhorn Y, Tyms AS. 1989. Persistence of cytomegalovirus in mononuclear cells in peripheral blood from blood donors. BMJ 299:897–898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6704.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor-Wiedeman J, Sissons JG, Borysiewicz LK, Sinclair JH. 1991. Monocytes are a major site of persistence of human cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Gen Virol 72:2059–2064. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-9-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McSharry BP, Avdic S, Slobedman B. 2012. Human cytomegalovirus encoded homologs of cytokines, chemokines and their receptors: roles in immunomodulation. Viruses 4:2448–2470. doi: 10.3390/v4112448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slobedman B, Barry PA, Spencer JV, Avdic S, Abendroth A. 2009. Virus-encoded homologs of cellular interleukin-10 and their control of host immune function. J Virol 83:9618–9629. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01098-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotenko SV, Saccani S, Izotova LS, Mirochnitchenko OV, Pestka S. 2000. Human cytomegalovirus harbors its own unique IL-10 homolog (cmvIL-10). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:1695–1700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lockridge KM, Zhou SS, Kravitz RH, Johnson JL, Sawai ET, Blewett EL, Barry PA. 2000. Primate cytomegaloviruses encode and express an IL-10-like protein. Virology 268:272–280. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones BC, Logsdon NJ, Josephson K, Cook J, Barry PA, Walter MR. 2002. Crystal structure of human cytomegalovirus IL-10 bound to soluble human IL-10R1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:9404–9409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152147499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spencer JV, Cadaoas J, Castillo PR, Saini V, Slobedman B. 2008. Stimulation of B lymphocytes by cmvIL-10 but not LAcmvIL-10. Virology 374:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spencer JV, Lockridge KM, Barry PA, Lin G, Tsang M, Penfold ME, Schall TJ. 2002. Potent immunosuppressive activities of cytomegalovirus-encoded interleukin-10. J Virol 76:1285–1292. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1285-1292.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avdic S, McSharry BP, Slobedman B. 2014. Modulation of dendritic cell functions by viral IL-10 encoded by human cytomegalovirus. Front Microbiol 5:337. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang WL, Barry PA, Szubin R, Wang D, Baumgarth N. 2009. Human cytomegalovirus suppresses type I interferon secretion by plasmacytoid dendritic cells through its interleukin 10 homolog. Virology 390:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang WL, Baumgarth N, Yu D, Barry PA. 2004. Human cytomegalovirus-encoded interleukin-10 homolog inhibits maturation of dendritic cells and alters their functionality. J Virol 78:8720–8731. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8720-8731.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raftery MJ, Hitzler M, Winau F, Giese T, Plachter B, Kaufmann SH, Schonrich G. 2008. Inhibition of CD1 antigen presentation by human cytomegalovirus. J Virol 82:4308–4319. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01447-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raftery MJ, Wieland D, Gronewald S, Kraus AA, Giese T, Schonrich G. 2004. Shaping phenotype, function, and survival of dendritic cells by cytomegalovirus-encoded IL-10. J Immunol 173:3383–3391. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkins C, Garcia W, Godwin MJ, Spencer JV, Stern JL, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. 2008. Immunomodulatory properties of a viral homolog of human interleukin-10 expressed by human cytomegalovirus during the latent phase of infection. J Virol 82:3736–3750. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02173-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkins C, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. 2004. A novel viral transcript with homology to human interleukin-10 is expressed during latent human cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol 78:1440–1447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1440-1447.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avdic S, Cao JZ, Cheung AK, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. 2011. Viral interleukin-10 expressed by human cytomegalovirus during the latent phase of infection modulates latently infected myeloid cell differentiation. J Virol 85:7465–7471. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00088-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung AK, Gottlieb DJ, Plachter B, Pepperl-Klindworth S, Avdic S, Cunningham AL, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. 2009. The role of the human cytomegalovirus UL111A gene in down-regulating CD4+ T-cell recognition of latently infected cells: implications for virus elimination during latency. Blood 114:4128–4137. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-197111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avdic S, Cao JZ, McSharry BP, Clancy LE, Brown R, Steain M, Gottlieb DJ, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. 2013. Human cytomegalovirus interleukin-10 polarizes monocytes toward a deactivated M2c phenotype to repress host immune responses. J Virol 87:10273–10282. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00912-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poole E, Avdic S, Hodkinson J, Jackson S, Wills M, Slobedman B, Sinclair J. 2014. Latency-associated viral interleukin-10 (IL-10) encoded by human cytomegalovirus modulates cellular IL-10 and CCL8 secretion during latent infection through changes in the cellular microRNA hsa-miR-92a. J Virol 88:13947–13955. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02424-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto-Tabata T, McDonagh S, Chang HT, Fisher S, Pereira L. 2004. Human cytomegalovirus interleukin-10 downregulates metalloproteinase activity and impairs endothelial cell migration and placental cytotrophoblast invasiveness in vitro. J Virol 78:2831–2840. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.2831-2840.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsonage G, Falciani F, Burman A, Filer A, Ross E, Bofill M, Martin S, Salmon M, Buckley CD. 2003. Global gene expression profiles in fibroblasts from synovial, skin and lymphoid tissue reveals distinct cytokine and chemokine expression patterns. Thromb Haemost 90:688–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saalbach A, Klein C, Schirmer C, Briest W, Anderegg U, Simon JC. 2010. Dermal fibroblasts promote the migration of dendritic cells. J Investig Dermatol 130:444–454. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schirmer C, Klein C, von Bergen M, Simon JC, Saalbach A. 2010. Human fibroblasts support the expansion of IL-17-producing T cells via up-regulation of IL-23 production by dendritic cells. Blood 116:1715–1725. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-263509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spencer JV. 2007. The cytomegalovirus homolog of interleukin-10 requires phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity for inhibition of cytokine synthesis in monocytes. J Virol 81:2083–2086. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01655-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saraiva M, O'Garra A. 2010. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat Rev Immunol 10:170–181. doi: 10.1038/nri2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otterbein LE, Soares MP, Yamashita K, Bach FH. 2003. Heme oxygenase-1: unleashing the protective properties of heme. Trends Immunol 24:449–455. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O'Garra A. 2001. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol 19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antoniv TT, Ivashkiv LB. 2011. Interleukin-10-induced gene expression and suppressive function are selectively modulated by the PI3K-Akt-GSK3 pathway. Immunology 132:567–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Garra A, Barrat FJ, Castro AG, Vicari A, Hawrylowicz C. 2008. Strategies for use of IL-10 or its antagonists in human disease. Immunol Rev 223:114–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Del Prete G, De Carli M, Almerigogna F, Giudizi MG, Biagiotti R, Romagnani S. 1993. Human IL-10 is produced by both type 1 helper (Th1) and type 2 helper (Th2) T cell clones and inhibits their antigen-specific proliferation and cytokine production. J Immunol 150:353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrat FJ, Cua DJ, Boonstra A, Richards DF, Crain C, Savelkoul HF, de Waal-Malefyt R, Coffman RL, Hawrylowicz CM, O'Garra A. 2002. In vitro generation of interleukin 10-producing regulatory CD4+ T cells is induced by immunosuppressive drugs and inhibited by T helper type 1 (Th1)- and Th2-inducing cytokines. J Exp Med 195:603–616. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y, Zhao H, Sun Y, Hao J, Qi X, Zhou X, Wu Z, Wang P, Kaech SM, Weaver CT, Flavell RA, Zhao L, Yao Z, Yin Z. 2013. IL-4 induces a suppressive IL-10-producing CD8+ T cell population via a Cdkn2a-dependent mechanism. J Leukoc Biol 94:1103–1112. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0213064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Waal Malefyt R, Abrams J, Bennett B, Figdor CG, de Vries JE. 1991. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J Exp Med 174:1209–1220. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staples KJ, Smallie T, Williams LM, Foey A, Burke B, Foxwell BM, Ziegler-Heitbrock L. 2007. IL-10 induces IL-10 in primary human monocyte-derived macrophages via the transcription factor Stat3. J Immunol 178:4779–4785. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sulahian TH, Hogger P, Wahner AE, Wardwell K, Goulding NJ, Sorg C, Droste A, Stehling M, Wallace PK, Morganelli PM, Guyre PM. 2000. Human monocytes express CD163, which is upregulated by IL-10 and identical to p155. Cytokine 12:1312–1321. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams L, Jarai G, Smith A, Finan P. 2002. IL-10 expression profiling in human monocytes. J Leukoc Biol 72:800–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricchetti GA, Williams LM, Foxwell BM. 2004. Heme oxygenase 1 expression induced by IL-10 requires STAT-3 and phosphoinositol-3 kinase and is inhibited by lipopolysaccharide. J Leukoc Biol 76:719–726. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0104046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park HJ, Lee SJ, Kim SH, Han J, Bae J, Kim SJ, Park CG, Chun T. 2011. IL-10 inhibits the starvation induced autophagy in macrophages via class I phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway. Mol Immunol 48:720–727. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogt PK, Hart JR. 2011. PI3K and STAT3: a new alliance. Cancer Discov 1:481–486. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weis N, Weigert A, von Knethen A, Brune B. 2009. Heme oxygenase-1 contributes to an alternative macrophage activation profile induced by apoptotic cell supernatants. Mol Biol Cell 20:1280–1288. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jenkins C, Garcia W, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. 2008. Expression of a human cytomegalovirus latency-associated homolog of interleukin-10 during the productive phase of infection. Virology 370:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mason GM, Poole E, Sissons JG, Wills MR, Sinclair JH. 2012. Human cytomegalovirus latency alters the cellular secretome, inducing cluster of differentiation CD4+ T-cell migration and suppression of effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:14538–14543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204836109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poole E, McGregor Dallas SR, Colston J, Joseph RS, Sinclair J. 2011. Virally induced changes in cellular microRNAs maintain latency of human cytomegalovirus in CD34+ progenitors. J Gen Virol 92:1539–1549. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.031377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slobedman B, Mocarski ES. 1999. Quantitative analysis of latent human cytomegalovirus. J Virol 73:4806–4812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]