ABSTRACT

For years, the S-layer glycoprotein (SLG), the sole component of many archaeal cell walls, was thought to be anchored to the cell surface by a C-terminal transmembrane segment. Recently, however, we demonstrated that the Haloferax volcanii SLG C terminus is removed by an archaeosortase (ArtA), a novel peptidase. SLG, which was previously shown to be lipid modified, contains a C-terminal tripartite structure, including a highly conserved proline-glycine-phenylalanine (PGF) motif. Here, we demonstrate that ArtA does not process an SLG variant where the PGF motif is replaced with a PFG motif (slgG796F,F797G). Furthermore, using radiolabeling, we show that SLG lipid modification requires the PGF motif and is ArtA dependent, lending confirmation to the use of a novel C-terminal lipid-mediated protein-anchoring mechanism by prokaryotes. Similar to the case for the ΔartA strain, the growth, cellular morphology, and cell wall of the slgG796F,F797G strain, in which modifications of additional H. volcanii ArtA substrates should not be altered, are adversely affected, demonstrating the importance of these posttranslational SLG modifications. Our data suggest that ArtA is either directly or indirectly involved in a novel proteolysis-coupled, covalent lipid-mediated anchoring mechanism. Given that archaeosortase homologs are encoded by a broad range of prokaryotes, it is likely that this anchoring mechanism is widely conserved.

IMPORTANCE Prokaryotic proteins bound to cell surfaces through intercalation, covalent attachment, or protein-protein interactions play critical roles in essential cellular processes. Unfortunately, the molecular mechanisms that anchor proteins to archaeal cell surfaces remain poorly characterized. Here, using the archaeon H. volcanii as a model system, we report the first in vivo studies of a novel protein-anchoring pathway involving lipid modification of a peptidase-processed C terminus. Our findings not only yield important insights into poorly understood aspects of archaeal biology but also have important implications for key bacterial species, including those of the human microbiome. Additionally, insights may facilitate industrial applications, given that photosynthetic cyanobacteria encode uncharacterized homologs of this evolutionarily conserved enzyme, or may spur development of unique drug delivery systems.

INTRODUCTION

A variety of protein complexes decorate cell surfaces, where they support cell stability and facilitate interactions between the cell and the extracellular environment (1–3). Determining the mechanisms that allow these proteins to remain associated with the cell envelope is critical for developing a comprehensive understanding of the biosynthesis of cell surface structures. Protein anchoring to the cell membrane was likely first accomplished by means of transmembrane (TM) segments (4). However, as cell membranes became densely packed with protein complexes, protein-anchoring mechanisms that allowed more economic use of membrane surface area emerged (5). One such mechanism anchors proteins through covalent attachment of their N-terminal cysteine to the lipid bilayer (6–8). In many Gram-positive bacteria, a subset of proteins are processed and anchored to the cell wall via the carboxy terminus (C terminus) by an enzyme known as sortase, a transpeptidase that recognizes a conserved tripartite structure at the C terminus consisting of a signature motif, a TM alpha-helical domain, and a cluster of basic residues (9). Following proteolytic cleavage of the substrate near its C terminus and formation of a covalent intermediate of the substrate with the sortase via a thioester bond, the sortase then transfers the substrate to a cell wall peptidoglycan precursor, resulting in covalent attachment of the substrate to the cell wall (10, 11).

In silico analyses by Haft et al. identified several species of Gram-negative bacteria and archaea that encode a set of Sec substrates that share a C-terminal domain structurally similar to the tripartite structure of the sortase substrates (12, 13). While species encoding these putative substrates lack sortase homologs, genome comparisons revealed that each genome encoding such substrates also encodes at least one member of a well-defined protein family, the exosortases and archaeosortases in bacteria and archaea, respectively (12, 13).

The first in vivo characterization of an archaeosortase was carried out in the model archaeon Haloferax volcanii (14), which has a cell wall consisting of a single protein, the S-layer glycoprotein (SLG) (15). This glycoprotein was previously thought to be anchored to the cell membrane by the intercalation of a C-terminal TM segment (15). However, we have demonstrated that this TM segment, which is part of a conserved tripartite structure, is processed in an archaeosortase A (ArtA)-dependent manner (14). In light of previous results demonstrating that this extensively studied cell wall subunit is lipid modified with archaetidic acid (2,3-di-O-phytanyl-sn-glycerylphosphate) (16–19), we hypothesized that ArtA also mediates proteolysis-coupled lipid modification. Cells lacking ArtA exhibit a growth defect, are relatively small, and have a severe motility defect (14). While some of these phenotypes are consistent with defects that might be caused by an unstable cell wall due to the improper surface anchoring of the unprocessed SLG, H. volcanii is predicted to contain eight additional ArtA substrates, so the failure to accurately process these other substrates might also contribute to the observed phenotypes (12).

In this study, we present data confirming that the S-layer glycoprotein is lipid modified in an ArtA-dependent manner. Moreover, a replacement mutant of the SLG in which the conserved tripeptide proline-glycine-phenylalanine (PGF) has been permutated to PFG is not processed, providing the first experimental confirmation of the importance of the PGF motif for ArtA processing. This mutant also allowed the identification of phenotypes that are, at least in part, due to an improperly anchored S-layer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

All enzymes used for standard molecular biology procedures were purchased from New England BioLabs. The ECL Prime Western blotting detection system and horseradish peroxidase-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. The polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, MF membrane filters (0.025 μm), and Ultracel-3K membrane were purchased from Millipore. The DNA and plasmid purification kits were purchased from Qiagen. NuPAGE gels, buffers, reagents, and the Pro-Q Emerald 300 glycoprotein stain kit were purchased from Invitrogen. Difco agar and Bacto yeast extract were purchased from Becton Dickinson and Company. Peptone was purchased from Oxoid. 5-Fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) was purchased from Toronto Research Biochemicals. [14C]mevalonic acid was a gift from Henry M. Miziorko, University of Missouri. All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from either Fisher or Sigma.

Strains and growth conditions.

The plasmids and strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. H. volcanii strains were grown at 45°C in solid agar (1.5%, wt/vol) with semidefined Casamino Acids (CA) medium supplemented with tryptophan and uracil (50-μg/ml final concentration) (20). H. volcanii strains transformed with pTA963 or its derivatives were grown in CA medium supplemented with tryptophan (50-μg/ml final concentration). For selection of the substitution mutants (see below), cells were grown at 45°C in CA medium supplemented with 5-FOA (150-μg/ml final concentration) and uracil (10-μg/ml final concentration). Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in NZCYM medium supplemented with ampicillin (200 μg/ml) (21).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pTA131 | Ampr; pBluescript II with BamHI-XbaI fragments from pGB70 harboring pfdx-pyrE2 | 22 |

| pTA231 | Ampr; pBluescript II with pHV2 replication origin harboring pfdx-trpA | 22 |

| pTA963 | Ampr, pyrE2 and hdrB markers, Trp-inducible (ptna) promoter | 24 |

| pAF9 | pTA963 carrying artA | 14 |

| pFH26 | pTA131 carrying fragment containing nucleotides encoding PFG with 400 bp flanking the intergenic region of slg and hvo_2073; the trpA gene cloned from pTA231 was inserted into the middle of the flanking fragments | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) phoA supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| DL739 | MC4100 recA dam-13::Tn9 | 39 |

| H. volcanii strains | ||

| H53 | ΔpyrE2 ΔtrpA | 24 |

| AF103 | H53 ΔartA | 14 |

| AF109 | AF103 containing pAF9 | 14 |

| ΔaglB mutant | H53 ΔaglB | 31 |

| FH37 | H53 ΔpyrE2 | This study |

| FH38 | H53 slgG796F,F797G ΔpyrE2 | This study |

Generation of chromosomal substitutions.

Chromosomal substitutions were generated using a homologous recombination (pop-in pop-out) method previously described by Allers et al. (22). To facilitate the recovery of mutant recombinants, the construct used for homologous recombination also contained the trpA gene (encoding the product with accession number gb|AAA72864.1) between slg (encoding the product with accession number gb|ADE05144.1) (400 nucleotides downstream of the SLG stop codon) and the downstream hvo_2073 gene (encoding the product with accession number WP_004041957.1) to minimize possible polar effects. Plasmid constructs were generated using overlap PCR as described previously (23). Upon homologous recombination, cells having trpA inserted into the chromosome were selected by growing them on CA agar plates lacking tryptophan. Recombinants were sequenced to identify the cell colonies containing an slg gene with the PFG codon mutation, slgG796F,F797G (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). An isogenic strain, FH37, containing the trpA gene insertion but having an unaltered slg PGF motif, was constructed and used as wild-type control.

Plasmid transformation.

The wild-type FH37, ΔartA, and slgG796F,F797G strains were transformed with nonmethylated plasmid pTA963 or pTA963 expressing ArtA (WP_004044024.1) (pAF9) (14), using the standard polyethylene glycol (PEG) transformation protocol (20). pTA963 is an overexpression vector derived from pBluescript II with the H. volcanii pHV2 replication origin in addition to both pyrE2 (encoding the product with accession number WP_004044590.1) and hdrB (encoding the product with accession number WP_004044748.1) markers. The plasmid also contains a 6×His tag at the multiple-cloning site (MCS) by the insertion of a 26-bp fragment of a (CAC)6 tract at the NdeI and PciI site (24).

CsCl purification of SLG.

The purification of SLG was performed by cesium chloride (CsCl) gradient centrifugation as described previously (25). Briefly, colonies from a solid-agar plate were inoculated into 5 ml CA liquid medium. Two liters of CA medium was inoculated with this 5-ml culture, and the cultures were harvested at optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 0.3 by centrifugation at 13,358 × g (JA-10 rotor; Beckman) for 30 min. The supernatant was centrifuged again (13,358 × g for 30 min) and incubated at room temperature with 4% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 6000 for 1 h. The PEG-precipitated proteins were then centrifuged at 39,175 × g (JLA 16.250) for 50 min at 4°C, and the SLG was purified by CsCl density gradient centrifugation (overnight centrifugation at 237,083 × g; VTI-65.1 rotor [Beckman]). CsCl was dissolved in a 3 M NaCl saline solution to a final density of 1.37 g cm−1.

Protein extraction, LDS-PAGE, and Coomassie blue staining.

Protein from cell pellets, CsCl purified samples, and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitations of H. volcanii strains were prepared, separated by lithium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (LDS-PAGE), and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue as previously described (14). Briefly, the liquid cultures were grown until the mid-log phase (OD600 of ∼0.5). Subsequently, cells were collected by centrifugation at 4,300 × g for 10 min. Cell pellets were resuspended and lysed in 1% LDS supplemented with 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The electrophoresis of the protein samples was performed with 7% Tris-acetate (TA) LDS-polyacrylamide gels under denaturing conditions by using TA running buffer. The Coomassie blue staining was carried out by incubating the gels with Coomassie brilliant blue G250 dye for 2 h, followed by washes in destaining 1 solution (40% methanol, 7% acetic acid) for 2 h and in destaining 2 solution (2% methanol, 8% acetic acid) for at least 6 h.

MS analysis.

The bands corresponding to SLG and SLGG796F,F797G from the CsCl-purified samples of wild-type FH37 and slgG796F,F797G strains, respectively, were excised from Coomassie blue-stained 7% TA LDS-polyacrylamide gels, followed by in-gel digestion with trypsin, as previously described (26, 27). Upon centrifugation of the digested sample, the resulting supernatants were dried in a vacuum centrifuge and reconstituted in 0.1% acetic acid for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. SLG samples were desalted as previously described (27).

A fused silica microcapillary column packed with Reprosil-pur C18 resin (3 μm; Dr. Maisch GmbH) was fitted with a fused silica emitter (New Objective; 10-μm tip). After using an Eksigent NanoLC AS-2 autosampler to load a sample, an Eksigent NanoLC 2D Plus high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) system was used to deliver a 2-phase gradient: 0.1% formic acid in water (A) or acetonitrile (B). The HPLC was coupled to a linear ion trap-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (LTQ-Orbitrap Elite; Thermo Scientific).

SLG peptides were separated over an 80-min gradient (250-μl/min constant flow): 2% B for 2 min, 12% B for 10 min, 35% B for 55 min, 95% B for 10 min, and 95% B for 5 min. A full MS spectrum was obtained at 60,000 resolution, followed by eight data-dependent tandem MS (MS/MS) acquisitions of the eight most abundant ions using higher-energy C-trap dissociation (HCD) fragmentation.

SLG data were analyzed by searching against an H. volcanii proteome database (UniProt; http://www.uniprot.org/taxonomy/309800) using SEQUEST (precursor mass tolerance, 10 pmm; fragment mass tolerance, 0.5 Da; maximum missed cleavages, 2; false-discovery rate, 0.1). Methionine oxidation was set as a variable modification, and cysteine carbamidomethylation was set as a fixed modification. Xcalibur Qual software was used for manual visualization and analysis of raw data. Abundance values were obtained by integrating the area under the extracted ion chromatogram (XIC). To correct for differences in protein loading between samples, abundance values were normalized to the average abundance of three internal peptides that were identified in both SLG and SLGG796F,F797G (amino acids [aa] 453 to 467, SGDGSSILSLTGTYR [m/z 757.379]; aa 579 to 588, VTAHILSVGR [m/z 526.814]; and aa 487 to 504, SLTTSEFTSGVSSSNSIR [m/z 930.453]), which should have the same relative abundance in both samples. Normalization was completed by dividing the raw abundance value of the peptide of interest by the average of the raw abundances of the three internal peptides.

Lipid radiolabeling.

The wild-type FH37, ΔartA, and slgG796F,F797G cells were grown in 5 ml liquid CA. Upon reaching mid-log phase (OD600, ∼0.5), 20 μl of each culture was transferred into 1 ml fresh liquid CA in which [14C]mevalonic acid, resuspended in ethanol, was added to a final concentration of 1 μCi/ml. The cultures were harvested after 24 h for the wild-type FH37, 96 h for the ΔartA strain, and 72 h for the slgG796F,F797G strain, when they had reached OD600s of 0.48, 0.41 and 0.40, respectively. Similar radiolabeling methods were also carried out for the wild-type strain carrying pTA963, the ΔartA strain carrying pTA963, and the ΔartA artA strain (FH37/pTA963, AF103/pTA963, and AF109, respectively). Proteins were precipitated from 1-ml cultures with 10% TCA, followed by delipidation as described previously (16, 17). The delipidated proteins were separated by 7% TA LDS-PAGE. For analysis of the samples, the gel was dried onto blotting paper using a Gel Dryer (Bio-Rad model 583), exposed to a phosphor screen (Molecular Dynamics) for 3 weeks, and analyzed using a Typhoon imager (Amersham Biosciences).

Glycosylation staining.

The cell lysates of the wild-type FH37, ΔartA, slgG796F,F797G, and ΔaglB strain cultures grown to mid-log phase (OD600, ∼0.5), were separated by 7% TA LDS-PAGE. The protein glycosylation was visualized using the Pro-Q Emerald 300 glycoprotein gel staining kit (Molecular Probes) as described previously (28).

Electron microscopy.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was carried out as previously described (14) with the following modifications. The wild-type/pTA963, ΔartA/pTA963, and slgG796F,F797G/pTA963 cells were grown in 5 ml liquid semidefined CA medium until they reached OD600s of 0.36, 0.33, and 0.47, respectively. Next, the cells were concentrated by centrifugation at 6,800 × g for 1 min, washed with 18% salt water, and examined using JEOL10 transmission electron microscope.

Growth curve.

Cultures for the wild-type FH37, ΔartA, and slgG796F,F797G strains were inoculated into 5 ml liquid CA medium from colonies and grown to an OD600 of ∼0.55. Subsequently, 10 μl of each culture was transferred to 5 ml liquid CA medium and grown to stationary phase, with OD600 readings taken every 3 to 4 h. The average OD600 readings of 10 replicates were used to construct the growth curve.

Light microscopy.

The wild-type FH37, ΔartA, and slgG796F,F797G strains were grown in 5 ml CA medium until they reached an OD600 of 0.4 to 0.5. Subsequently, 2 ml of each culture was concentrated by centrifugation at 4,911 × g for 1 min, and pellets were resuspended in 10 μl of liquid CA medium. Then, 1 μl of the concentrated cells was transferred to a microscope slide and observed using the light microscope as described previously (14).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The PGF motif is critical for ArtA-dependent SLG C-terminal processing.

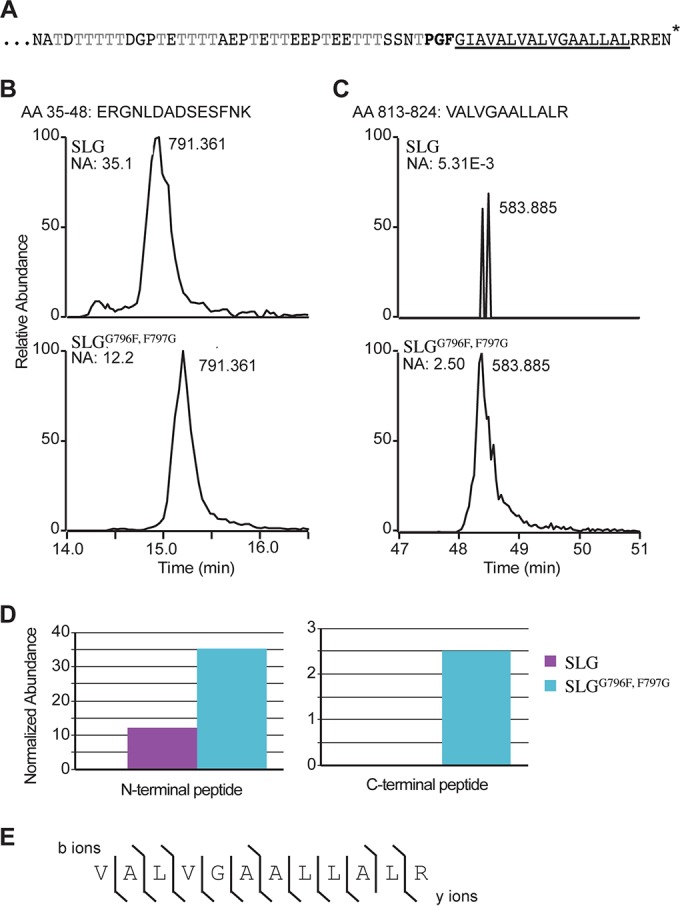

To determine whether the conserved PGF motif is indeed critical for ArtA-dependent C-terminal processing, we engineered an SLG substitution mutant in which the codon encoding the conserved PGF motif was mutated to a PFG motif (Fig. 1A). In silico analysis revealed that the glycine and phenylalanine of this highly conserved motif, found at the start of the conserved C-terminal tripartite structure of predicted ArtA substrates, are invariant, suggesting that the motif is crucial for ArtA recognition (12). Using homologous recombination, the slgG796F,F797G strain was constructed, in which a chromosomal copy of slg was replaced with an slgG796F,F797G mutation and selected for by a trpA gene inserted downstream (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Additionally, an isogenic strain encoding an unaltered SLG C-terminal PGF motif with an exactly corresponding trpA insertion, FH37, was also constructed. This strain, which exhibits wild-type morphology and growth phenotypes, was used as the wild-type control in our experiments.

FIG 1.

The conserved SLG PGF motif is critical for ArtA-dependent processing. (A) The SLG C-terminal region (aa 766 to 827) consists of a threonine-rich stretch followed by the conserved PGF motif (bold), a hydrophobic stretch (underlined), and positively charged residues (*, end of protein). (B and C) XICs of gel-purified SLG and SLGG796F,F797G peptides from aa 35 to 48 (B) and aa 813 to 824 (C), respectively. The masses and normalized abundances (NA) of the chromatographic peak are indicated. (D) Graphical representation of the relative abundances of the N-terminal peptide (aa 35 to 48) and C-terminal peptide (aa 813 to 824) in wild-type SLG (purple) and SLGG796F,F797G (blue) cells. (E) MS/MS fragment ions from C-terminal peptide aa 813 to 824 ([M + 2H]2+ = 583.885 m/z). The lines indicate which fragment ions were detected (b ions above the sequence; y ions below). Identification of a large number of the expected fragment ions lends strong support that the peptide was correctly identified.

The SLG and SLGG796F,F797G variant protein constructs were purified from the supernatants of the respective strain cultures, using CsCl density gradient centrifugation. Proteins in CsCl gradient fractions containing the SLG or SLGG796F,F797G were separated using LDS-PAGE. Purified SLGG796F,F797G, which, similar to the SLG purified from ΔartA supernatants, migrated slightly faster than SLG purified from the wild-type supernatants (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) (14), was trypsin digested in the gel, and subjected to mass spectrometry analysis (26). SEQUEST analysis of these trypsin-digested peptides revealed that both the SLG and SLGG796F,F797G mutant construct yielded similar peptides (SLG coverage, 12.8%; SLGG796F,F797G coverage, 20.6%), including the N-terminal peptide of SLG, upon signal peptidase I processing. Total extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) revealed that this N-terminal peptide (aa 35 to 48) has very similar abundance (same order of magnitude) and elutes simultaneously in the SLG and SLGG796F,F797G samples (SLG, 12.2; SLGG796F,F797G, 35.1 [normalized abundance]) (Fig. 1B and D). Consistent with previous results, mass spectrometric analysis of the trypsin-digested wild-type SLG detected statistically insignificant levels of peptides, essentially equivalent to background noise, that were derived from the C-terminal end of the protein subsequent to the PGF motif (Fig. 1C and D). This result is in accordance with the C-terminal region being processed by ArtA (14). Conversely, similar to SLG isolated from the ΔartA strain, the C-terminal peptide aa 813 to 824 (VALVGAALLALR) (Fig. 1C and D) was readily detected for digested SLGG796F,F797G (3 orders of magnitude higher abundance than wild-type SLG). MS/MS fragmentation of the C-terminal peptide yielded near complete coverage of the possible fragment ions, lending strong support that it was correctly identified (Fig. 1E). These results, in combination with the finding that the N-terminal peptide is found in roughly equal abundance, lend strong support that the C-terminal peptide is not processed in the SLGG796F,F797G and that ArtA processing requires that a substrate contain the conserved PGF motif. It is possible that the retention of the C-terminal domain results in faster migration of the SLGG796F,F797G than of the SLG on the LDS-polyacrylamide gels due to altered detergent binding to the hydrophobic stretch (29).

At this stage, the mass spectrometric analysis that we carried out on the digested SLG was unsuccessful in identifying either the ArtA processing site or the lipid moiety that modifies this glycoprotein. The inability to identify these posttranslational modifications is due to challenges in determining the C-terminal peptide mass of the processed SLG, as this region contains a stretch of threonine amino acid residues, which are potential targets for O-glycosylation, a poorly understood posttranslational modification in archaea (15).

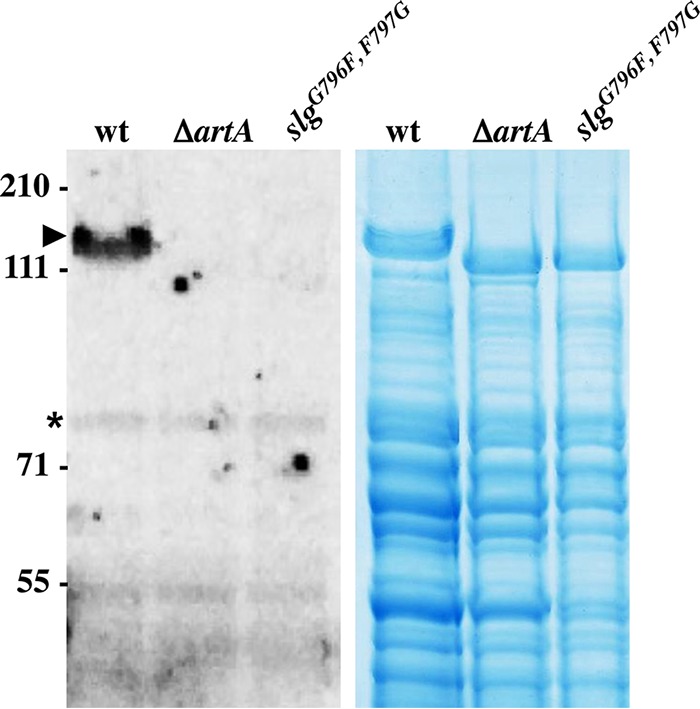

H. volcanii SLG is lipid modified in an ArtA-dependent manner.

Radiolabeled mevalonic acid, a natural prenyl group precursor in archaeal lipid biosynthesis pathways, was previously shown to be incorporated into the mature SLG (16, 17). Recently, this lipid covalent linkage to the SLG has been determined to specifically involve the archaetidic acid (2,3-di-O-phytanyl-sn-glycerylphosphate) (18, 19). However, the molecular machineries involved in creating this covalent lipid linkage to the SLG had not yet been elucidated. To determine whether this SLG lipid modification is ArtA dependent, we carried out [14C]mevalonic acid radiolabeling on the wild-type and ΔartA strains. After proteins in delipidated radiolabeled cell extracts were separated by LDS-PAGE, fluorography of the gels detected a significant band at the size corresponding to the SLG in protein extracts isolated from wild-type cells, while no signal was detected in that region of the gel for cell extracts of strains lacking ArtA (Fig. 2). It is unlikely that the failure to detect SLG labeling in the ΔartA strain extracts was due to a defective uptake or incorporation of the radiolabeled mevalonic acid into the cytoplasmic membrane, as additional lower-molecular-weight radiolabeled bands were reproducibly observed for protein in cell extracts from both the wild-type and ΔartA cells. These low-molecular-weight radiolabeled proteins perhaps represent the ArtA-independent N-terminally lipidated lipoproteins. Lipobox-containing H. volcanii proteins, in which an invariant cysteine near the N terminus of the mature protein is essential for processing the signal peptide and is required for cell surface anchoring in a subset of proteins, have previously been characterized (30). These results, suggesting that SLG lipid modification is ArtA dependent, were further supported by the finding that SLG radiolabeling was restored when the chromosomal artA deletion was complemented by artA overexpression in trans (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). ArtA-dependent radiolabeled protein bands other than the SLG were not observed in this fluorography, which might be expressed at low concentrations or may not be expressed at all under the conditions tested. Conversely, Coomassie blue staining of proteins separated by LDS-PAGE suggests that SLG, as indicated by its corresponding protein band previously defined by mass spectrometry and Western blot analysis (Fig. 1; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) (14), is highly abundant in both wild-type and ΔartA cell extracts, underscoring the fact that the lack of a signal in the fluorograph was not due to low protein abundance (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

ArtA and the conserved C-terminal PGF motif are required for H. volcanii SLG lipid modification. Left, fluorography of protein extracts isolated from wild-type FH37 (wt), ΔartA, and slgG796F,F797G cells grown in the presence of 1 μCi/ml [14C]mevalonic acid. Labeled SLG (arrowhead) is detected only in the wt extract. Additional labeled lower-molecular-weight proteins likely are ArtA-independent secreted lipobox-containing proteins (asterisk) (30). Right, Coomassie blue stain of protein extracts from wt, ΔartA, and slgG796F,F797G cells. The migration of molecular mass standards is indicated on the left (in kDa).

The SLGG796F,F797G mutant protein is not lipid modified.

To determine the importance of the conserved PGF motif for lipid modification, we also carried out [14C]mevalonic acid labeling on the H. volcanii slgG796F,F797G mutant, as described above. Similar to results that were obtained for the SLG isolated from the ΔartA strain, fluorographic analysis failed to detect the radiolabeled SLGG796F,F797G (Fig. 2). This finding strongly suggests that the SLG lipid modification not only is ArtA dependent but also requires the conserved C-terminal PGF motif. Since neither the SLG expressed in the ΔartA strain nor SLGG796F,F797G is covalently lipid modified, it is also possible that the absence of this lipid moiety contributes to the unusual migration behavior of these proteins on the LDS-polyacrylamide gel (17).

Alternatively, it is also possible that the lack of other posttranslational modifications, such as glycosylations, contributes to the migration shifts of the SLG isolated from the ΔartA strain and the SLGG796F,F797G. However, the LDS-PAGE glycostaining demonstrated that both the SLG of the ΔartA strain and SLGG796F,F797G are glycosylated (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The SLG obtained from a strain lacking the oligosaccharyltransferase AglB (WP_013035363.1), which is required for N-glycosylation under optimal salt concentrations, exhibits migration behavior similar to that of the wild type, suggesting that the lack of AglB-dependent N-glycosylation of the SLG is insufficient to cause such a migration shift (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) (31). However, since N-glycosylation of the SLG can involve at least one additional, poorly understood, N-glycosylation pathway (32), as well as at least one O-glycosylation pathway (15) whose components to date remain elusive, determining whether either of these pathways may be responsible for the SLG migration shift presents challenges and is beyond the scope of this paper.

The slgG796F,F797G strain growth and cell morphology defects are only slightly less severe then those of the ΔartA strain.

We previously reported that the ΔartA strain exhibits severe growth and morphology defects, phenotypes that can be complemented by expressing ArtA in trans (14). These phenotypic defects of the ΔartA strain may be due solely to improper anchoring of the SLG to the cell membrane or could be due at least in part to the lack of processing of the other ArtA substrates (14). In the slgG796F,F797G mutant strain, presumably, all of the other ArtA substrates are processed properly, so observing phenotypic defects matching those of the ΔartA strain would indicate that those defects are specifically due to disrupted processing of the SLG. Therefore, we first determined the growth curve for the slgG796F,F797G strain in semidefined CA medium and found that the slgG796F,F797G strain displays a growth defect similar to that of the ΔartA strain (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). It should be noted that transformation of the ΔartA strain but not the slgG796F,F797G strain with the pyrE2-bearing expression plasmid pTA963 (from which we derived the construct used to overexpress ArtA [pAF9] for the complementation studies [see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material] [14]) in CA medium lacking uracil to select for the transformants causes a more severe growth defect than is displayed by the nontransformed mutant strains grown in uracil-supplemented CA medium (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). It is possible that the addition of uracil to nontransformed culture aids growth, possibly since the pTA963 pyrE2 gene required for uracil biosynthesis was used as its selective marker for the transformants (24). The transformants may have had a growth disadvantage because they rely on the pTA963 pyrE2 gene product for the uracil biosynthesis, in contrast to the case for the untransformed cells, where uracil was readily available in the medium. pTA963 also contains a replication origin derived from the H. volcanii natural plasmid pHV2, which has yet to be fully characterized, and its replication may impose an additional metabolic cost to the cells compared to the untransformed cells (24, 33).

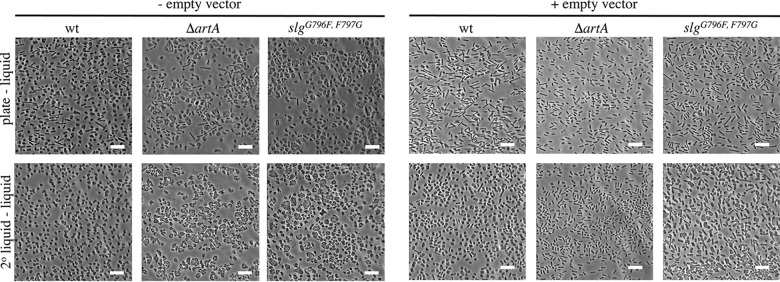

Since the presence of pTA963 affected the growth rate of the ΔartA strain, cell morphology analyses were performed for both sets of cultures. Using light microscopy to examine cells from cultures of untransformed cells grown in liquid CA medium, we determined that wild-type cells, inoculated from colonies grown on agar plates, are predominantly pleomorphic disk-shaped cells (∼300 cells per panel), while approximately 20% of the cells are rod shaped with an average cell length of approximately 3.9 μm (standard deviation [SD], 1.5 μm). A similar portion of the ΔartA strain cultures are rod shaped; however, these rods are shorter (2.2 μm; SD, 1.1 μm) than the wild-type rods. While there appear to be fewer disk-shaped cells in the ΔartA strain cultures (∼200 cells per panel) than in the wild-type sample, the highly irregular shapes and large size of these cells, compared to those of the wild-type cells, suggest that the ΔartA cells may be forming aggregates or are enlarged due to abnormal cell division (34). The slgG796F,F797G cultures also contain irregular disk-shaped cells (∼250 cells per panel), as well as rod-shaped cells of shorter average length (2.3 μm; SD, 0.3 μm); however, the percentage of rods is reduced to approximately 2% (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

The ΔartA and slgG796F,F797G strains exhibit distinct cell morphology compared to the wild type. Phase-contrast microscopy of wild-type FH37 (wt), ΔartA, and slgG796F,F797G without or with pTA963 grown to mid-log phase in liquid semidefined CA medium supplemented with tryptophan and uracil or with tryptophan only, respectively, is shown. Liquid medium was inoculated with cells from colonies grown on solid CA agar plates (top row) or cells that had been grown by serial transfer in liquid medium to mid-log phase (bottom row). Size bars, 10 μm.

The presence of the pTA963 plasmid has little or no effect on the average length of rods observed among either the wild-type or slgG796F,F797G cells, with average lengths of 3.9 μm (SD, 1.3 μm) and 2.9 μm (SD, 1.2 μm), respectively. In contrast, the ΔartA rod-shaped transformants are slightly shorter, with an average length of 1.8 μm (SD, 0.3 μm). Moreover, in cultures of cells containing the plasmid, approximately 90% of wild-type and slgG796F,F797G transformants, and 100% of ΔartA transformants, are rods (Fig. 3).

Interestingly, while serial transfers of the liquid wild-type culture to new liquid medium results in more than 90% disk-shaped cells, regardless of whether the cells contain the plasmid, the morphology phenotypes of the mutants vary significantly from that of the wild-type cells upon extended liquid-to-liquid transfer. For both the slgG796F,F797G and ΔartA strains, after two transfers in liquid medium, untransformed cells are highly pleomorphic and appear to form clumps of highly deformed disk-shaped cells. Moreover, approximately 75% of slgG796F,F797G cells transformed with pTA963 are rod shaped upon initial liquid-to-liquid transfer (data not shown), with 53% remaining rod shaped after a second transfer. Most unexpectedly, ΔartA cells transformed with pTA963 remained exclusively rod shaped even after two liquid-to liquid transfers (Fig. 3).

The biological significance of, and the underlying mechanisms involved in, regulating archaeal cell morphology has only recently begun to be fully appreciated (34). Here we report that the lack of proper processing and anchoring of surface proteins can affect the ability of cells to alter their cell morphology. Based on our results, it appears that one or more ArtA substrates play a critical role in this process. Based on the inability of ΔartA cells and, to a lesser extent, cells expressing the SLG replacement mutant, but not wild-type cells, to morph from rod-shaped to disk-shaped cells, additional analyses and characterizations of the ArtA substrates may allow us to identify specific proteins involved in regulating cell morphology and may ultimately lead to the discovery of the molecular mechanisms that allow cells to modify their shapes as conditions demand.

Moreover, while the more severe growth and morphology phenotypes exhibited by the mutant transformants suggest that the ArtA-mediated surface protein processing and anchoring are not limited to the SLG, the phenotypes of the slgG796F,F797G strain also underscore the importance of ArtA-mediated processing and anchoring of the SLG for growth and maintenance of cell morphology (35).

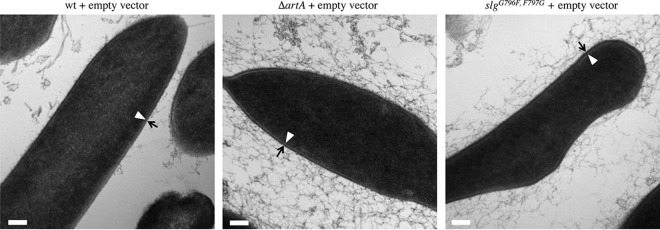

The S-layer of slgG796F,F797G cells is thicker then that of wild-type cells.

TEM of thin sections of wild-type and ΔartA cells previously revealed that the mutant strain has a thicker cell wall (14). Considering that morphological differences may also affect cell wall thickness, we used similar technique to compare the S-layer thicknesses of slgG796F,F797G cells to those of ΔartA and wild-type cells, using cells transformed with pTA963, as the rod-shape morphology is predominant among these cells upon inoculation from colonies grown on solid agar plates into semidefined CA liquid medium (Fig. 3).

Despite having an unprocessed C terminus and lacking lipid anchoring, the mutant SLG of an slgG796F,F797G strain transformed with pTA963 can be assembled into an S-layer, similar to the SLG in ΔartA cells. While the average thickness of S-layers of the slgG796F,F797G transformants is approximately 16 nm (SD, 1.6 nm), S-layers of wild-type and ΔartA transformants have similar average thicknesses (12 nm) (SD, 2.6 nm and 2.4 nm, respectively) (Fig. 4). Unlike wild-type or slgG796F,F797G transformants, ΔartA cells are surrounded by substantial amounts of additional loose material. Although the origin and composition of this material are unclear, based on its proximity to the cell wall, it is possible that it is S-layer that has been shed. Supporting this notion, we observed that while the majority of wild-type cells are devoid of this material, the few cells surrounded by loose material exhibit a reduced S-layer width, averaging 9.5 nm. It is possible that under the growth conditions used, the presence of pTA963 or the use of semidefined CA growth medium (the cells examined previously [14] were grown on complex medium) imposes greater stress on the ΔartA strain, causing a large fraction of its unstable S-layer to be shed into its surrounding environment. It is also possible that the unstable S-layer is extremely sensitive to mechanical stress exerted by the centrifugal force applied to the cultures, even at a low speed, for concentrating and washing the cells prior to high-pressure freezing preservation. While the material is also present in the slgG796F,F797G cultures, it is less abundant than in the ΔartA cultures, suggesting that in the slgG796F,F797G strain, proper processing and anchoring of ArtA substrates other than the SLG may sufficiently stabilize the S-layer to prevent mass shedding.

FIG 4.

SLGG796F,F797G forms a thicker S-layer than the wild type. Wild-type FH37 (wt), ΔartA, and slgG796F,F797G cells transformed with pTA963 were preserved with high-pressure freezing techniques, followed by thin-slice section microscopy. The S-layer thickness was determined by measuring the region between the cell membrane (arrowhead) and the outer edge of the S-layer (arrow). The slgG796F,F797G cells contain a wider S-layer (16 nm) than the wt (12 nm) and contain material around the cells. While displaying an S-layer with a width similar to that of the wt, the ΔartA cells generally contained significant amounts of material surrounding the cell compared to the other strains. Size bars, 100 nm.

Alternatively, this material might be cytoplasmic content released into the extracellular environment by lysed cells, which would indirectly suggest that the ΔartA cells face a severe cell stability issue under the conditions tested. This is consistent with the more severe growth defect exhibited by ΔartA transformants, particularly when grown in low-salt media, in which defects in cell wall anchoring and processing of additional ArtA substrates may leave the fragile cells more prone to lysis (14). In either case, this underscores the importance of proper anchoring of the SLG as well as the other ArtA substrates for maintaining cell stability in the high-salinity environment.

Concluding remarks.

Anchoring mechanisms involving either N- or C-terminal transmembrane segments have been well characterized in bacteria and archaea (1, 36–38). However, while anchoring mechanisms involving N-terminal covalently attached lipids have been studied in detail in bacteria (6, 8) and archaeal proteins requiring the invariant lipobox cysteine for proper surface attachment have been identified (30), this is the first report to present evidence consistent with protein anchoring of secreted prokaryotic proteins that is mediated through the covalent attachment of a cell membrane lipid to the C terminus. Our findings provide a sound foundation for future biochemical and molecular biological studies that will allow us to fully understand the mechanisms underpinning the ArtA-dependent processing and lipidation of the C terminus of the SLG.

The research described here also provides a basis on which to initiate studies aimed at identifying the functions of bacterial exosortases and their substrates, which, although present in a highly diverse set of bacteria, have not yet been studied in vivo. Future investigations of lipid-anchored proteins, as well as comparisons of the organisms that use these lipid-mediated protein-anchoring strategies to those that use other anchoring strategies, will clarify the benefits and limitations of this protein-anchoring mechanism. These comparisons, combined with complementary in vivo studies, will be crucial to gaining a greater understanding of prokaryotic cell surface biogenesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Fevzi Daldal, Phil Rea, Friedhelm Pfeiffer, and the Pohlschroder lab for helpful discussions. We thank Henry M. Miziorko for providing us with the [14C]mevalonic acid.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00849-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albers S-V, Meyer BH. 2011. The archaeal cell envelope. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:414–426. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster TJ, Geoghegan JA, Ganesh VK, Höök M. 2014. Adhesion, invasion and evasion: the many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thanassi DG, Bliska JB, Christie PJ. 2012. Surface organelles assembled by secretion systems of Gram-negative bacteria: diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36:1046–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renthal R. 2010. Helix insertion into bilayers and the evolution of membrane proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci 67:1077–1088. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0234-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pohlschröder M, Hartmann E, Hand NJ, Dilks K, Haddad A. 2005. Diversity and evolution of protein translocation. Annu Rev Microbiol 59:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zückert WR. 2014. Secretion of bacterial lipoproteins: through the cytoplasmic membrane, the periplasm and beyond. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843:1509–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutchings MI, Palmer T, Harrington DJ, Sutcliffe IC. 2009. Lipoprotein biogenesis in Gram-positive bacteria: knowing when to hold 'em, knowing when to fold 'em. Trends Microbiol 17:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buddelmeijer N. 2015. The molecular mechanism of bacterial lipoprotein modification—how, when and why? FEMS Microbiol Rev 39:246–261. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuu006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneewind O, Missiakas D. 2014. Sec-secretion and sortase-mediated anchoring of proteins in Gram-positive bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843:1687–1697. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ton-That H, Liu G, Mazmanian SK, Faull KF, Schneewind O. 1999. Purification and characterization of sortase, the transpeptidase that cleaves surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus at the LPXTG motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:12424–12429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perry AM, Ton-That H, Mazmanian SK, Schneewind O. 2002. Anchoring of surface proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. III. Lipid II is an in vivo peptidoglycan substrate for sortase-catalyzed surface protein anchoring. J Biol Chem 277:16241–16248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haft DH, Payne SH, Selengut JD. 2012. Archaeosortases and exosortases are widely distributed systems linking membrane transit with posttranslational modification. J Bacteriol 194:36–48. doi: 10.1128/JB.06026-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haft DH, Paulsen IT, Ward N, Selengut JD. 2006. Exopolysaccharide-associated protein sorting in environmental organisms: the PEP-CTERM/EpsH system. Application of a novel phylogenetic profiling heuristic. BMC Biol 4:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdul Halim MF, Pfeiffer F, Zou J, Frisch A, Haft D, Wu S, Tolic N, Brewer H, Payne SH, Pasa-Tolic L, Pohlschroder M. 2013. Haloferax volcanii archaeosortase is required for motility, mating, and C-terminal processing of the S-layer glycoprotein. Mol Microbiol 88:1164–1175. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sumper M, Berg E, Mengele R, Strobel I. 1990. Primary structure and glycosylation of the S-layer protein of Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol 172:7111–7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kikuchi A, Sagami H, Ogura K. 1999. Evidence for covalent attachment of diphytanylglyceryl phosphate to the cell-surface glycoprotein of Halobacterium halobium. J Biol Chem 274:18011–18016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.18011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konrad Z, Eichler J. 2002. Lipid modification of proteins in Archaea: attachment of a mevalonic acid-based lipid moiety to the surface-layer glycoprotein of Haloferax volcanii follows protein translocation. Biochem J 366:959–964. doi: 10.1042/bj20020757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kandiba L, Guan Z, Eichler J. 2013. Lipid modification gives rise to two distinct Haloferax volcanii S-layer glycoprotein populations. Biochim Biophys Acta 1828:938–943. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishimura Y, Eguchi T. 2006. Biosynthesis of archaeal membrane lipids: digeranylgeranylglycerophospholipid reductase of the thermoacidophilic archaeon Thermoplasma acidophilum. J Biochem 139:1073–1081. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyall-Smith M. 2004. The Halohandbook—protocols for haloarchaeal genetics. University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: http://www.haloarchaea.com/resources/halohandbook/Halohandbook_2009_v7.2mds.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blattner FR, Williams BG, Blechl AE, Denniston-Thompson K, Faber HE, Furlong L, Grunwald DJ, Kiefer DO, Moore DD, Schumm JW, Sheldon EL, Smithies O. 1977. Charon phages: safer derivatives of bacteriophage lambda for DNA cloning. Science 196:161–169. doi: 10.1126/science.847462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allers T, Ngo H-P, Mevarech M, Lloyd RG. 2004. Development of additional selectable markers for the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii based on the leuB and trpA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:943–953. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.2.943-953.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tripepi M, Imam S, Pohlschroder M. 2010. Haloferax volcanii flagella are required for motility but are not involved in PibD-dependent surface adhesion. J Bacteriol 192:3093–3102. doi: 10.1128/JB.00133-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allers T, Barak S, Liddell S, Wardell K, Mevarech M. 2010. Improved strains and plasmid vectors for conditional overexpression of His-tagged proteins in Haloferax volcanii. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:1759–1769. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02670-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tripepi M, You J, Temel S, Önder Ö, Brisson D, Pohlschröder M. 2012. N-glycosylation of Haloferax volcanii flagellins requires known Agl proteins and is essential for biosynthesis of stable flagella. J Bacteriol 194:4876–4887. doi: 10.1128/JB.00731-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin S, Garcia BA. 2012. Examining histone posttranslational modification patterns by high-resolution mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol 512:3–28. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-391940-3.00001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shevchenko A, Tomas H, Havlis J, Olsen JV, Mann M. 2006. In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat Protoc 1:2856–2860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinberg TH, Pretty On Top K, Berggren KN, Kemper C, Jones L, Diwu Z, Haugland RP, Patton WF. 2001. Rapid and simple single nanogram detection of glycoproteins in polyacrylamide gels and on electroblots. Proteomics 1:841–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rath A, Glibowicka M, Nadeau VG, Chen G, Deber CM. 2009. Detergent binding explains anomalous SDS-PAGE migration of membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:1760–1765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813167106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Storf S, Pfeiffer F, Dilks K, Chen ZQ, Imam S, Pohlschröder M. 2010. Mutational and bioinformatic analysis of haloarchaeal lipobox-containing proteins. Archaea 2010. doi: 10.1155/2010/410975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abu-Qarn M, Yurist-Doutsch S, Giordano A, Trauner A, Morris HR, Hitchen P, Medalia O, Dell A, Eichler J. 2007. Haloferax volcanii AglB and AglD are involved in N-glycosylation of the S-layer glycoprotein and proper assembly of the surface layer. J Mol Biol 374:1224–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaminski L, Guan Z, Yurist-Doutsch S, Eichler J. 2013. Two distinct N-glycosylation pathways process the Haloferax volcanii S-layer glycoprotein upon changes in environmental salinity. mBio 4:e00716-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00716-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenshine I, Tchelet R, Mevarech M. 1989. The mechanism of DNA transfer in the mating system of an archaebacterium. Science 245:1387–1389. doi: 10.1126/science.2818746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duggin IG, Aylett CH, Walsh JC, Michie KA, Wang Q, Turnbull L, Dawson EM, Harry EJ, Whitchurch CB, Amos LA, Lowe J. 2015. CetZ tubulin-like proteins control archaeal cell shape. Nature 519:362–365. doi: 10.1038/nature13983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mescher MF, Strominger JL. 1976. Structural (shape-maintaining) role of the cell surface glycoprotein of Halobacterium salinarium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 73:2687–2691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.8.2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dalbey RE, Wang P, Kuhn A. 2011. Assembly of bacterial inner membrane proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 80:161–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060409-092524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luirink J, Yu Z, Wagner S, de Gier J-W. 2012. Biogenesis of inner membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta 1817:965–976. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giménez MI, Dilks K, Pohlschröder M. 2007. Haloferax volcanii twin-arginine translocation substates include secreted soluble, C-terminally anchored and lipoproteins. Mol Microbiol 66:1597–1606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blyn LB, Braaten BA, Low DA. 1990. Regulation of pap pilin phase variation by a mechanism involving differential dam methylation states. EMBO J 9:4045–4054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.