ABSTRACT

In this study, we examined the peripheral blood (PB) central memory (TCM) CD4+ T cell subsets designated peripheral T follicular helper cells (pTfh cells) and non-pTfh cells to assess HIV permissiveness and persistence. Purified pTfh and non-pTfh cells from healthy HIV-negative donors were tested for HIV permissiveness using green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing HIV-1NL4-3/Ba-L, followed by viral reactivation using beads coated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies. The role of pTfh cells in HIV persistence was analyzed in 12 chronically HIV-1 infected patients before and 48 weeks after initiation of raltegravir-containing combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). Total cellular HIV-1 DNA and episomes containing two copies of the viral long terminal repeat (2LTR circles) were analyzed in using droplet digital PCR in the purified pTfh and non-pTfh cells. Activation-inducible HIV p24 expression was determined by flow cytometry. Results indicate that pTfh cells, in particular PD1+ pTfh cells, showed greater permissiveness for HIV infection than non-pTfh cells. At week 48 on cART, HIV DNA levels were unchanged from pre-cART levels, although a significant decrease in 2LTR circles was observed in both cell subsets. Inducible HIV p24 expression was higher in pTfh cells than in non-pTfh cells, with the highest frequencies in the PD1+ CXCR3− pTfh cell subset. Frequencies of HLADR+ CD38+ activated CD4 T cells correlated with 2LTR circles in pTfh and non-pTfh cells at both time points and with p24+ cells at entry. In conclusion, among CD4 TCM cells in PB of aviremic patients on cART, pTfh cells, in particular the PD1+ CXCR3− subset, constitute a major HIV reservoir that is sustained by ongoing residual immune activation. The inducible HIV p24 assay is useful for monitoring HIV reservoirs in defined CD4 T cell subsets.

IMPORTANCE Identification of the type and nature of the cellular compartments of circulating HIV reservoirs is important for targeting of HIV cure strategies. In lymph nodes (LN), a subset of CD4 T cells called T follicular helper (Tfh) cells are preferentially infected by HIV. Central memory (TCM) CD4 T cells are the major cellular reservoir for HIV in peripheral blood and contain a subset of CD4 TCM cells expressing chemokine receptor CXCR5 similar in function to LN Tfh cells termed peripheral Tfh (pTfh) cells. We found that the circulating pTfh cells are highly susceptible to HIV infection and that in HIV-infected patients, HIV persists in these cells following plasma virus suppression with potent cART. These pTfh cells, which constitute a subset of TCM CD4 T cells, can be readily monitored in peripheral blood to assess HIV persistence.

INTRODUCTION

Treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has resulted in significant reduction in morbidity and mortality associated with HIV infection, but it is not curative and does not eradicate the HIV reservoirs. Initiation of cART markedly reduces plasma HIV burden to levels undetectable by commercially available assays (1, 2). However, the ultrasensitive single-copy assay can still detect HIV RNA in peripheral blood at extremely low levels that persist even after several years of treatment (3). This observation points to the presence of a transcriptionally active reservoir of HIV-infected cells that continues to produce viruses despite potent cART. This reservoir appears to be remarkably stable, as several treatment intensification studies have shown that adding antiretroviral agents to the standard cART does not eradicate this low-level viremia (4–6). The major reason why HIV persists despite antiretroviral treatment is its ability to establish a latent infection in long-lived memory CD4+ T cells (7, 8). Latently infected cells contain integrated HIV DNA that is transcriptionally silent, but upon activation, these cells are capable of producing infectious virus. This cellular reservoir decays very slowly, with a half-life of 40 to 44 months, indicating that more than 70 years of intensive therapy would be required for its elimination (9). Studies by Chomont et al. have identified central memory (TCM) and transitional memory (TTM) CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood as the main viral reservoirs in HIV-infected subjects under viral-suppressive ART (10). Most proviral DNA was detected in TCM cells among patients with higher CD4 counts, whereas those with poorer immune reconstitution had more HIV DNA in TTM cells, indicating variability across patients in terms of T cell subset infection. Recently, a population of even more highly immature memory CD4+ T cells with stem cell-like properties (TSCM) has been described to harbor HIV DNA (11). Persistence of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) in different subpopulations of CD4+ T cells is a major barrier to HIV eradication despite cART, and it is critically important to define the cellular subsets that harbor HIV.

Emerging data point to germinal-center T follicular helper (GC-Tfh) cells in lymph nodes (LN) as reservoirs of HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). These cells expand in LN during chronic HIV and SIV infection (12–14) and are highly permissive for HIV and SIV (14–18). A recent study showed that productive SIV infection occurs in resident intrafollicular CD4+ Tfh cells within the B cell follicles in lymph nodes of SIV-infected elite controller rhesus macaques (19) and are shielded from cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. It has been suggested that latent infection is established in circulating memory CD4+ T cells as they pass through chemokine-rich environments, such as lymph nodes (20, 21).

In the peripheral blood, a subset of CD4 TCM cells expressing CXC chemokine receptor 5 (CXCR5) is important for antibody production (22–24). These cells have been termed as peripheral T follicular helper cells (pTfh cells), as they share functional properties with GC-Tfh cells and are capable of providing help to B cells to produce antibodies by promoting somatic hypermutation and class-switch recombination (22–25). The true relationship between pTfh and lymphoid Tfh cells has not yet been established, but experimental studies with mice (26) suggest that circulating pre-Tfh cells enter lymphoid follicles and traffic to GCs as mature Tfh cells; recent data imply that GC-Tfh cells exit the LN as memory cells (27). We hypothesized that pTfh cells are a key subset of circulating memory CD4 T cells and could constitute an important HIV reservoir. We reasoned that the TCM characteristics of the pTfh cells would provide ideal conditions for viral persistence due to their higher rate of proliferation and lower susceptibility to undergo apoptosis (9).

In this work, we highlight the following observations: (i) the pTfh CD4 T cell subset of HIV-negative individuals is highly permissive to HIV infection and manifests inducible virus reactivation upon ex vivo cellular activation; (ii) in HIV-infected, virologically suppressed patients, pTfh cells have evidence of HIV reservoirs which are sustained by immune activation of pTfh cells; and (iii) the inducible HIV p24 flow cytometry assay is a practical tool for monitoring HIV reservoirs in different subsets of CD4 T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study groups.

This study was performed as an extension of our previous studies on immune reconstitution analysis of HIV-infected participants in the A009 protocol (ClinicalTrials registration number [Clinicaltrials.gov] NCT00654147) as previously described (28). Briefly, A009 was a prospective, 48-week randomized open-label pilot study of raltegravir (RAL)-containing cART (RAL-cART) in treatment-naive chronically HIV-infected patients with plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of ≥5,000 copies/ml. RAL at 400 mg twice a day (BID) was administered in combination with either lopinavir at 400 mg and ritonavir at 100 mg BID (Kaletra) or emtricitabine at 200 mg and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate at 300 mg. Immunologic assessment and virus load determinations were performed at study entry (week 0) and at weeks 4, 8, 24, and 48 (28). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and plasma samples were cryopreserved as per approved guidelines (29). Demographic characteristics and detailed analysis of immune reconstitution of these patients at entry and different time points on RAL-cART were published previously (28). For the present study, PBMC from 12 participants were examined for viral reservoir analysis at entry and after 48 weeks of cART. The median age of the participants was 40.5 years (range, 24 to 53); the participants had a plasma HIV RNA level of 5.35 ± 5.47 log10 copies/ml, an absolute CD4 T cell count of 330 ± 206/μl and an absolute CD8 T cell count of 990 ± 362/μl (means ± standard deviations). All HIV-infected patients had suppressed viremia, with <50 HIV RNA copies/ml of plasma, for >24 weeks at the time of the 48-week blood sample, and the mean absolute CD4 T cells increased from entry to 588 ± 285 cells/μl (P = 0.0187). Ten HIV-seronegative volunteers served as healthy controls (HC) for pTfh cell phenotypic analysis. This study was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board, and all participants signed informed-consent forms. For HIV infectivity assays, PBMC were prepared from buffy coats obtained from five healthy adult volunteers by density gradient isolation (30) and processed directly for memory CD4 T cell isolation. A negative HIV antibody (Ab) test by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) confirmed the HIV infection status of the buffy coat samples.

Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), cell separation kits, and reagents.

CD3-AmCyan, CD3-peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP), CD4-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD45RO-phycoerythrin (PE)-Texas red, CD27-Alexa Fluor 700, CCR7-PE-Cy7, CXCR5-Alexa Fluor 647, CCR5-PE, PD1-allophycocyanin (APC)-Cy7, CD69-Alexa Fluor 700, HLA-DR-PerCP, Ki67-PerCpCy5.5, CXCR3-Alexa Fluor 700, CCR6-PE, and CD38-PE-Cy5 were purchased from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA. CD45RO-PE-Texas Red (PE-TR) and anti-p24-FITC (KC57-FITC) were obtained from Beckman Coulter. A LIVE/DEAD fixable violet dead cell stain (ViViD) kit, CD4-Qdot655, and CD8 Q-dot605 were purchased from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen), Eugene, OR. Saquinavir and raltegravir were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH.

Preparation of HIV-1 virions expressing EGFP.

HIV-1 NL4-3/Ba-L-EGFP is a macrophage-tropic recombinant clone of pNL4-3 containing the CCR5-utilizing envelope from HIV-1BaL and expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in infected cells. Construction of the proviral construct HIV-1 NL4-3/Ba-L-EGFP has been previously described by our group (31). HIV stocks were prepared by harvesting the supernatant of 293T cells transfected with NL4-3/Ba-L-EGFP. 293T cells were transfected with 5 μg of pNL4Ba-L-EGFP plasmid using Genjet plus transfection reagent (Signagen Laboratories, Iamsville, MD). Twenty-four hours following transfection, plates were washed twice with serum-free medium and replaced with Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 24 h. Cell culture supernatant was collected, clarified by centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 min, and filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). To prepare high-titer stocks, viral particles were concentrated by repeated low-speed centrifugation using YM-50 ultrafiltration units (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Aliquots (1 ml) of virus were cryopreserved at −80°C, and the concentration of virus was determined with an Alliance HIV-1 p24 antigen ELISA kit (PerkinElmer, Inc., MA).

Cell sorting for isolation of pTfh and non-pTfh cells.

To avoid nonspecific cellular activation, fresh PBMC or cryopreserved PBMC that had been rested for 4 h after thawing were processed to isolate memory CD4 T cells (CD45RA−) by negative selection with the EasySep human memory CD4 T cell enrichment kit (Stemcell Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol and sorted on a BD FACS Aria to obtain pTfh and non-pTfh cell subsets at purities of ≥99%. Briefly, negatively selected memory CD4 T cells were stained with ViViD, CD4-Qdot655, CXCR5-Alexa Fluor 647, and CCR7-PE-Cy7 to sort ViViDneg CD4+ memory CD4 T cells that were pTfh (CCR7+ CXCR5+) and non-pTfh (CCR7+ CXCR5neg) cells. Isolated CD4 T cells were washed and resuspended in R-10 medium. For flow cytometry-based inducible HIV p24 analysis, PBMC from HIV-infected patients were depleted of CD8 T cells by positive selection using a CD8 positive selection kit (Stemcell Technologies).

In vitro HIV infection assay.

Sort-purified pTfh and non-pTfh cells were counted, collected as pellets by centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 min at room temperature, and resuspended in R-10 medium. A fraction of the cells were activated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) (5 μg/ml) and 100 U/ml of interleukin 2 (IL-2) for 3 days, and another part was rested overnight. Both activated and nonactivated cells were infected by spinoculation with the appropriate volume of concentrated viral supernatant. Approximately 200 ng of p24gag per 4 × 105 sorted cell subsets was used. Spinoculation was performed in 96-well V-bottom plates in volumes of 200 μl or less with up to 5 × 105 CD4 T cells per well at 1,200 × g for 2 h at room temperature. After spinoculation, cells were pooled and cultured at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and supplemented with 5 μM saquinavir for 3 days to prevent residual spreading infection. Infection was analyzed by flow cytometry based on the frequencies of infected (GFP+) cells with each cell population.

Reactivation of HIV-1 from cells infected without preactivation.

Cells were spinoculated with GFP-expressing HIV-1 NL4-3/Ba-L without PHA activation. On day 3 after spinoculation, cells were counted and collected as pellets by centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 min. Cells were then plated in 96-well U-bottom plates at concentrations of 2.5 × 105 to 1 × 106/200 μl in the presence of 30 μM raltegravir and beads coated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 MAbs at a ratio of 1:1 for 3 days. Cells cultured alone were used as controls. After 3 days, cells were analyzed for HIV infection by GFP expression.

pTfh cell phenotyping and immune activation by flow cytometry.

In patient samples, phenotypic characteristics of the pTfh cells were determined at entry and at week 48 on cART. Cells were stained for basic surface markers (CD3 and CD4), markers specific for pTfh cell phenotypes (CXCR5, CXCR3, and PD1), maturation markers (CD45RO, CD27, and CCR7), activation markers (HLA-DR and CD38), and HIV coreceptor (CCR5). Cells were stained with surface markers at room temperature, fixed, permeabilized, and stained intracellularly for Ki67. ViViD staining was used for excluding dead cells, and fluorescence minus one (FMO) was used to optimize gating. Cells were acquired on a BDFortessa flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo (Ashland, OR) software (TreeStar 9.7.6). Flow cytometry analysis was performed after proper instrument setting, calibration, and compensation (32, 33). Live memory CD4 T cells (ViViDneg CD3+ CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+) were further gated based on the expression of CCR7 and CXCR5 into pTfh (CCR7+ CXCR5+) and non-pTfh (CCR7+ CXCR5neg) cell subsets. Both pTfh and non-pTfh cells were further divided into subsets based on the expression of CXCR3 and PD1 as CXCR3neg PD1+, CXCR3+ PD1+, CXCR3+ PD1neg, and CXCR3neg PD1neg subsets. pTfh and non-pTfh cells and their subsets were further analyzed for markers of immune activation and HIV coreceptor expression.

In addition, sorted pTfh and non-pTfh cells from the buffy coat samples were analyzed for the expression of activation markers (HLA-DR and Ki67) and HIV coreceptor (CCR5) and PD1 preactivation and after PHA activation.

Inducible HIV p24 flow cytometry assay.

CD8-depleted PBMC (2 × 106 cells/ml) were cultured with medium alone or activated for induction of HIV p24 with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads at a 1:1 ratio for 72 h at 37°C in the presence of 30 μM raltegravir to prevent de novo infection of cells (34). After incubation, cells were stained for phenotypic surface markers specific for pTfh cells and ViViD, fixed, permeabilized, and stained intracellularly using an optimized concentration of anti-p24 Abs at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were acquired immediately on a BDFortessa and analyzed using FlowJo software. Total CD4, pTfh, and non-pTfh cell subsets were analyzed for intracellular p24 expression (35, 36).

HIV-1 DNA analysis.

To further confirm our inducible p24 expression and HIV reservoirs, CD8-depleted PBMC, sorted pTfh cells, and non-pTfh cells were further analyzed for total HIV DNA, episomes containing two copies of the viral long terminal repeat (2LTR circles), and human CCR5 as described previously (37, 38). Total DNA was purified from cells using QIAamp DNA blood minikits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Primers and fluorogenic probes were designed to quantitate total HIV-1 clade B genomes, 2LTR episomal DNA, and human CCR5 (37, 38). All targets were measured by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) using a Bio-Rad QX100 ddPCR instrument. ddPCR allows precise determination of target DNA copy number that exceeds that possible with current PCR methods. The dynamic range of detection for ddPCR is 1 to 105 copies. Sensitivity for 2LTR circles is estimated to be 0.7 to 3 copies/million cells. All of the target amplicons were cloned into plasmids and used as positive controls to validate the assay. The single-copy human CCR5 gene was quantified to measure the number of cell equivalents in DNA samples for standardization (37, 38).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 6.02). Differences in the HIV infectivity between pTfh and non-pTfh cells and expression of various phenotypic markers relevant to infection were analyzed using an unpaired 2-tailed Student's t test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

pTfh cells are more permissive to HIV infection than non-pTfh cells, with PD1+ pTfh cells being the most permissive.

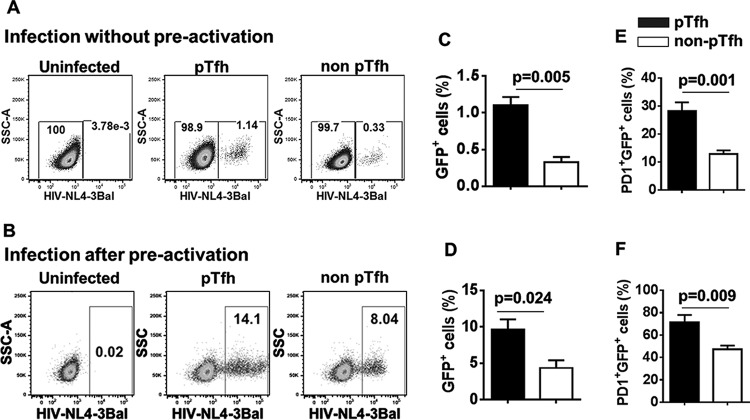

Since Tfh cells in the LN are preferentially infected by HIV (12), we sought to analyze the HIV permissiveness of pTfh and non-pTfh cells using sort-purified cell subsets from five healthy donors. Target cells were spinoculated with GFP-expressing HIV-1 NL4-3/Ba-L without prior activation or after 3 days of in vitro activation with PHA. The pTfh cells were more permissive for HIV than non-pTfh cells either with or without preactivation. Without preactivation, the mean frequency of GFP+ cells within pTfh cells was 1.1 ± 0.3, whereas in non-pTfh cells, it was 0.32 ± 0.16 (Fig. 1A and C). After 3 days of preactivation with PHA, the mean frequency of GFP+ cells in pTfh cells was 9.6 ± 3.2, while that in non-pTfh cells was 4.3 ± 2.4 (Fig. 1B and D). To further analyze the phenotypic characteristics of infected versus uninfected cells, we investigated the GFP expression in gated PD1+ CCR5+ HLA-DR+ Ki67+ pTfh and non-pTfh cells. We noted an association between PD1 expression and HIV permissiveness in pTfh and non-pTfh cells. PD1+ pTfh cells showed significantly higher frequencies of GFP+ cells with (20.2 ± 7.1 versus 11.04 ± 4.3) or without (5.3 ± 2.1 versus 1.02 ± 0.7) preactivation than did PD1+ non-pTfh cells, indicating the importance of PD1 in HIV persistence. When GFP+ cells were analyzed for PD1 expression, we found higher frequencies of PD1 expression in GFP+ pTfh cells than in GFP+ non-pTfh cells when infected either with (71.2 ± 14.2 versus 47. 2 ± 7.4) or without (28.2 ± 6.8 versus 12.8 ± 3.07) preactivation (Fig. 1E and F).

FIG 1.

pTfh cells are more permissive to HIV infection than non-pTfh cells. Memory CD4 T cells were negatively isolated from buffy coat PBMC (n = 5) and sorted for pTfh (CXCR5+ CCR7+) and non-pTfh (CXCR5neg CCR7+) cells. Sort-purified cells were infected with GFP-expressing macrophage-tropic HIV-1 NL4-3/Ba-L and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are representative flow cytometry dot plots depicting HIV infection in pTfh and non-pTfh cells, when cells were infected, without activation (A) and after 3 days of PHA activation (B). Bar graphs present the mean frequencies of GFP+ cells when cells were infected without preactivation (C) and after PHA activation (D) and mean frequencies of PD1+ cells within infected (GFP+) cells when cells were infected without preactivation (E) and after PHA activation (F).

pTfh cells infected in vitro without preactivation showed higher levels of GFP expression after restimulation using beads coated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 MAbs.

We employed a straightforward approach using cells that were spinoculated with HIV without preactivation and then activated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads for 3 days in the presence of raltegravir to prevent de novo infection. As shown in Fig. 2, 3-fold-higher frequencies of GFP+ cells in pTfh cells and 1.5-fold-higher frequencies of GFP+ cells in non-pTfh cells were evident following activation compared to the values prior to activation. When PD1+ cells were analyzed, 20% ± 3.6% of the PD1+ pTfh cells showed GFP expression, compared to 3.9% ± 1.6% (P = 0.002) of the PD1+ non-pTfh cells. These results demonstrate the capacity of pTfh cells to produce inducible virus when they are activated.

FIG 2.

pTfh cells infected in vitro with HIV-1 NL4-3/Ba-L-EGFP in the absence of activation show higher levels of GFP expression after restimulation with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads. Memory CD4 T cells were negatively isolated from buffy coat PBMC (n = 5) and sorted for pTfh (CXCR5+ CCR7+) and non-pTfh (CXCR5neg CCR7+) cells. Sort-purified cells were infected with GFP-expressing macrophage-tropic HIV-1 NL4-3/Ba-L without preactivation for 3 days. On day 3, cells were activated for induction of HIV with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots showing GFP expression within pTfh and non-pTfh cells after reactivation. (B) Bar graphs represent the mean frequencies of GFP+ cells within pTfh and non-pTfh cells with and without reactivation.

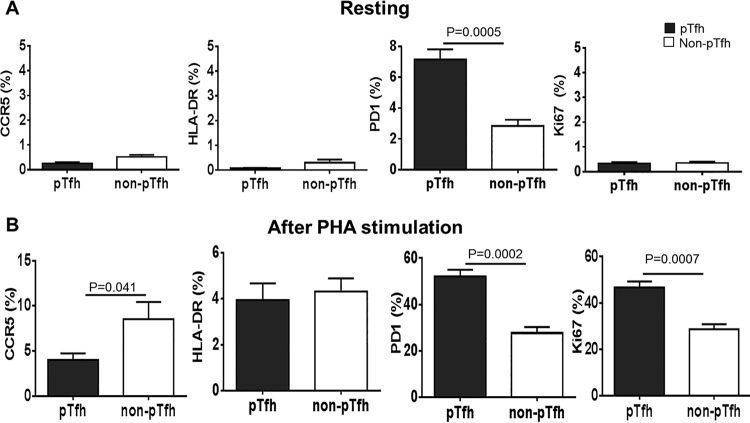

Phenotypic analysis of pTfh cells before and after in vitro activation.

We analyzed the expression of immune activation markers, HIV-1 coreceptor, and PD1 on pTfh and non-pTfh cells with and without in vitro activation to understand if any difference in the expression of these markers would contribute to HIV permissiveness of pTfh cells. No significant difference in the expression of activation markers (HLA-DR and Ki67) and HIV-1 coreceptor (CCR5) was observed in either pTfh or non-pTfh cells before activation (Fig. 3A). Expression of PD1 was significantly higher (P = 0.0005) in pTfh cells than in non-pTfh cells before activation (Fig. 3A). After 3 days of PHA activation, CCR5, HLA-DR, PD1, and Ki67 were upregulated (Fig. 3B), although CCR5 expression was lower in pTfh cells than in non-pTfh cells. Interestingly, PD1 expression after PHA stimulation was significantly higher in pTfh cells than in non-pTfh cells (P = 0.0002). Ki67 expression after PHA stimulation was also significantly higher in pTfh cells than in non-pTfh cells (P = 0.0007).

FIG 3.

pTfh cells show higher expression of PD1 before and after in vitro activation. Memory CD4 T cells were negatively isolated from buffy coat PBMC and sorted for pTfh (CXCR5+ CCR7+) and non-pTfh (CXCR5neg CCR7+) cells and analyzed for phenotypic markers either without stimulation or after 3 days of PHA stimulation. (A) pTfh and non-pTfh cells expressing HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5, HLA-DR, PD1, and Ki67 before activation. (B) pTfh and non-pTfh cells expressing HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5, HLA-DR, PD1, and Ki67 after 3 days of PHA activation.

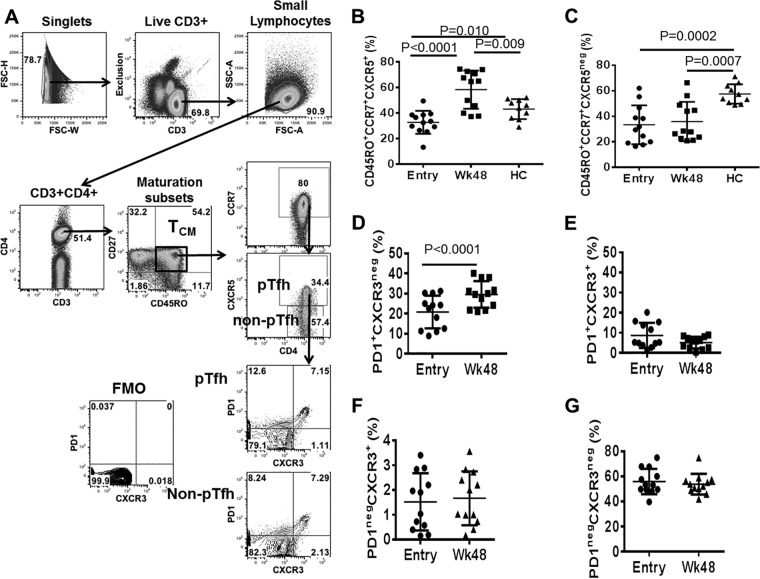

cART restores frequencies of pTfh cells and reduces their activation state.

An extensive analysis of immune reconstitution following cART in this cohort of HIV-infected patients was published by our group previously (28). In the present study, we restricted our analysis to pTfh and non-pTfh cells within the TCM CD4 T cells to define their role as HIV reservoirs. The gating strategy for identification of pTfh and non-pTfh cells is shown in Fig. 4A. Frequencies of pTfh and non-pTfh cells were significantly lower at entry in the patient group than in healthy controls (HC) (Fig. 4B and C). In accordance with our previous observations that frequencies of TCM CD4 T cells increase at week 48 after cART initiation (28), we found frequencies of pTfh cells to be higher at week 48 than pre-cART levels and also higher than in HC (Fig. 4B). However, frequencies of non-pTfh cells did not change at week 48, indicating a selective increase in frequencies of pTfh cells after initiation of cART in these patients (Fig. 4C). We further analyzed the pTfh cell subsets based on the expression of PD1 and CXCR3 and found that pTfh cell expansion at week 48 was restricted to the PD1+ CXCR3neg subset (Fig. 4D). Frequencies of the PD1+ CXCR3+ (Fig. 4E), PD1neg CXCR3+ (Fig. 4F), and PD1neg CXCR3neg (Fig. 4G) subsets did not change significantly at week 48. Taken together, our results indicate altered kinetics of TCM CD4 T cell subsets following cART during HIV infection. Within pTfh cells, ART-induced increase in frequency was restricted to the PD1+ CXCR3neg subset, indicating that there was a selective reconstitution of TCM CD4 T cells following ART.

FIG 4.

Frequencies of pTfh cells are increased following 48 weeks of cART in treatment-naive patients. Cryopreserved PBMC from study participants and healthy controls (HC) were thawed, rested overnight, and stained for markers specific for pTfh cell phenotyping along with LIVE/DEAD stain. (A) Gating strategy for pTfh cells and for pTfh cell subset identification based on PD1 and CXCR3 expression; (B to G) scatter plots showing frequencies of pTfh (B) and non-pTfh (C) cells at entry and week 48 on cART and frequencies of PD1+ CXCR3neg (D), PD1+ CXCR3+ (E), PD1neg CXCR3+ (F), and PD1neg CXCR3neg (G) pTfh cell subsets at entry and week 48 on cART.

We further analyzed the immune activation phenotype of pTfh and non-pTfh cells as measured by the frequencies of cells with HLA-DR and CD38 dual expression at entry and at week 48 on cART. As shown in Fig. 5A, a significant decrease in immune activation was observed in total CD4 T cells at week 48, to levels comparable to those in HC. As expected, frequencies of HLA-DR+ CD38+ pTfh and non-pTfh cells decreased significantly at week 48 in comparison to those at entry (Fig. 5B). Unlike the observation in total CD4 T cells, immune activation in pTfh and non-pTfh cells was still higher at week 48 than in HC (Fig. 5B), indicating persistent immune activation of the CD4 TCM compartment even after suppression of virus replication. Interestingly, the levels of immune activation were higher in the pTfh compartment than in the non-pTfh cells at entry (P = 0.009) and at week 48 (P = 0.0007). Moreover, pTfh cells in HC also showed higher frequencies of activated cells than non-pTfh cells (P = 0.001), indicating an overall higher state of immune activation in the pTfh compartment than in the non-pTfh compartment. Based on the selective expansion of PD1+ CXCR3neg pTfh cell subsets at week 48, we analyzed the immune activation of pTfh cell subsets. Immune activation of the PD1+ CXCR3neg subset did not decrease at week 48, indicating a sustained level of immune activation (Fig. 5C). However, the PD1+ CXCR3+ pTfh subset showed a significantly lower level of immune activation at week 48 (Fig. 5D). The other two pTfh cell subsets (PD1neg CXCR3+ [Fig. 5E] and PD1neg CXCR3neg [Fig. 5F]) and all non-pTfh cell subsets based on PD1 and CXCR3 expression showed decreases in immune activation at week 48 compared to pre-cART levels (Fig. 5G to J).

FIG 5.

cART reduces activation state of pTfh and non-pTfh cells after 48 weeks of treatment. Cryopreserved PBMC from study participants were thawed, rested overnight, and stained for markers specific for pTfh cell phenotyping along with LIVE/DEAD staining and markers of immune activation (HLA-DR and CD38). Scatter plots show total CD4 (A) and pTfh and non-pTfh cells (B) depicting dual expression of HLA-DR and CD38 at entry and week 48 on cART in comparison to HC. In addition, scatter plots show dual expression of HLA-DR and CD38 at entry and week 48 on cART in pTfh cell subsets (C to F) and non-pTfh cell subsets (G to J) based on PD1 and CXCR3 expression.

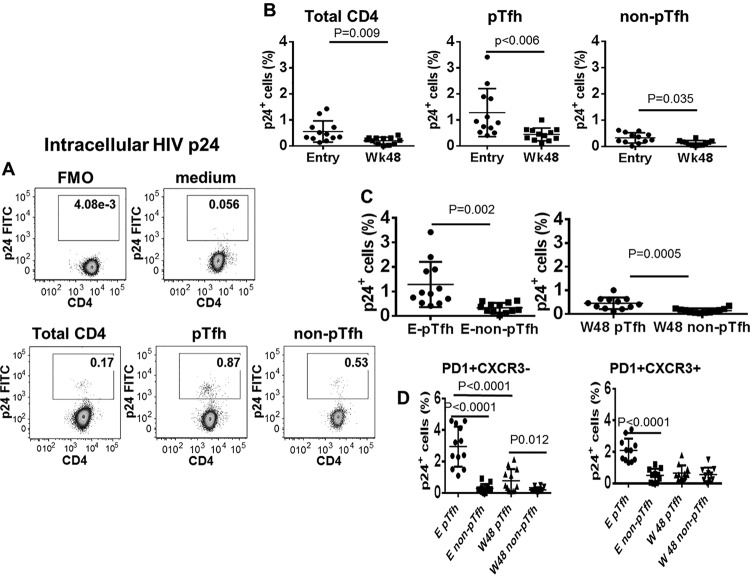

Frequencies of pTfh cells with inducible HIV are greater than frequencies of non-pTfh cells and decrease at week 48 of cART.

Recent studies have identified a major role for Tfh cells in the LN as HIV reservoirs in cART-treated individuals (12, 19). To establish the role of pTfh cells as HIV reservoirs, CD8-depleted PBMC were activated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads for 3 days, and cells were analyzed for HIV p24 expression by flow cytometry as a marker of viral replication (Fig. 6A). Total CD4, pTfh, and non-pTfh cells showed HIV p24 expression after anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation that decreased at week 48 (Fig. 6B). Frequencies of HIV p24+ cells were significantly higher in the pTfh compartment than in non-pTfh cells at entry (1.2 ± 0.7 versus 0.33 ± 0.19; P < 0.0001) and also at week 48 (0.4 ± 0.3 versus 0.13 ± 0.09; P = 0.01) (Fig. 6C). PD1+ CXCR3neg pTfh cells manifested higher p24-expressing cells after anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation than did PD1+ CXCR3neg non-pTfh cells at entry and at week 48 (Fig. 6D). Our data indicate that transcriptionally active HIV can be identified from pTfh cells of virally suppressed HIV-infected patients on cART, demonstrating that pTfh cells constitute a reservoir where replication-competent virus persists.

FIG 6.

Frequencies of HIV p24 inducible cells are higher in pTfh than in non-pTfh cells. CD8-depleted PBMC were activated for induction of HIV with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation and surface stained for markers for pTfh phenotyping, followed by intracellular staining for HIV-p24. (A) Flow cytometric dots plots showing p24 expression in CD4 T cells and pTfh and non-pTfh cells; (B to D) scatter plots showing mean frequencies of p24 expression in total CD4, pTfh and non-pTfh cells (B and C) and p24 expression in PD1+ CXCR3− and PD1+ CXCR3+ pTfh subsets (D).

Total HIV DNA remains unchanged but 2LTR circles decrease in pTfh and non-pTfh cells at week 48.

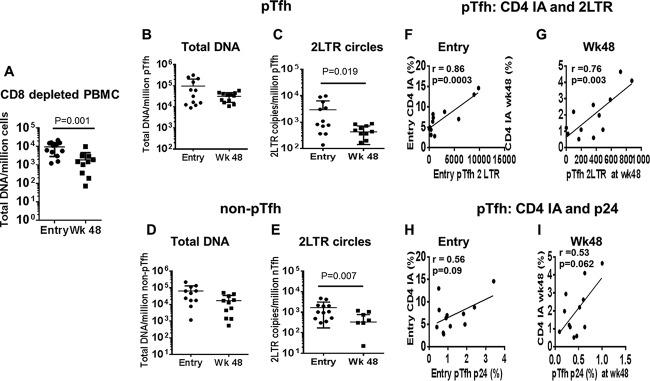

To further understand the role of pTfh cells in HIV persistence, we analyzed total HIV DNA levels and 2LTR circles in purified pTfh and non-pTfh cells at entry and at week 48 on cART. Total DNA decreased significantly at week 48 in CD8-depleted PBMC samples (Fig. 7A). Although a trend of decrease was observed, total HIV DNA did not change significantly at week 48 in pTfh and non-pTfh compartments compared to entry levels (Fig. 7B and D). Although HIV DNA levels at entry were not significantly different in pTfh and non-pTfh cells, the differences were statistically significant at week 48 (P = 0.041). However, 2LTR circles were significantly lower at week 48 than at entry in both pTfh and non-pTfh compartments (Fig. 7C and E). At week 48, the levels of 2LTR circles were significantly higher in pTfh cells than in non-pTfh cells (428 ± 286.3 versus 177.7 versus 232.9; P = 0.028). Moreover, 2LTR circles at week 48 were detectable in 11/12 (91.7%) patients and in non-pTfh cells in 7/12 (58.3%) patients, indicating the importance of pTfh cells in contributing to the reservoir of HIV-infected cells that continues to produce viruses during potent cART.

FIG 7.

2LTR circles decrease in pTfh and non-pTfh cells at week 48 and correlate with CD4 T cell activation. Sort-purified populations of pTfh and non-pTfh cells were subjected to analysis of total HIV-DNA and 2LTR circles by real-time PCR and droplet digital PCR, respectively. Scatter plots show total HIV DNA in CD8-depleted PBMC (A), total HIV DNA and 2LTR circles in pTfh cells (B and C), and total HIV DNA and 2LTR circles in non-pTfh cells (D and E) at entry and at week 48 on cART. Correlations between CD4 T cell immune activation with 2LTR DNA levels in pTfh cells at entry and week 48 on cART (F and G) and frequencies of p24 expression in pTfh cells at entry and week 48 on cART (H and I) are also shown.

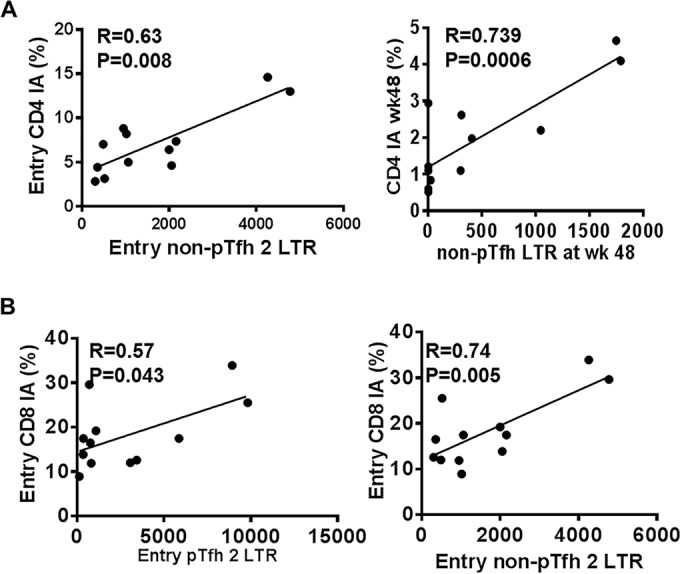

Activated CD4 T cells correlate with frequencies of 2LTR circles and HIV p24+ pTfh cells.

We next analyzed the association of HIV reservoirs in pTfh and non-pTfh cells with an immune activation phenotype at entry and week 48. Total HIV DNA in pTfh and non-pTfh cells did not correlate with immune activation of CD4 and CD8 T cells either at entry or at week 48 (data not shown). However, frequencies of 2LTR circles in pTfh cells correlated with immune activation in pTfh cells at entry and week 48 (Fig. 7F and G). At week 48, frequencies of 2LTR circles in pTfh cells also correlated with activated total CD4 T cells (r = 0.775; P = 0.005). In addition, CD4 T cell immune activation also showed a correlation with non-pTfh cells expressing 2LTR circles at entry and at week 48 (Fig. 8A). Activation of CD8 T cells showed a correlation with 2LTR circles in pTfh and non-pTfh cells only at entry (Fig. 8B).The frequency of p24+ pTfh cells also showed a trend toward a direct correlation with CD4 immune activation at entry and at week 48 (Fig. 7H and I).

FIG 8.

CD8 T cell immune activation at entry correlates with 2LTR DNA in pTfh and non-pTfh cells at entry. Sort-purified populations of pTfh and non-pTfh cells were subjected to 2LTR circles analysis by droplet digital PCR. Correlations between CD4 IA at entry and week 48 with 2LTR DNA in non-pTfh cells at entry and week 48 (A) and CD8 T cell immune activation at entry with entry pTfh and non-pTfh 2LTR circles (B) are shown.

DISCUSSION

T follicular helper cells are specialized memory CD4 T helper cells that are critical for providing help to B cells to generate high-affinity antibodies (25, 39). Recent studies have ascribed an important role for Tfh cells in the LN in contributing to HIV persistence (12, 19). LN Tfh cells in rhesus macaques and humans show preferential infection with SIV and HIV (12–14, 16–19, 40), pointing to these cells as potential reservoirs for HIV. In peripheral blood, there is a subset of cells within the TCM CD4 T cell compartment that express the chemokine receptor CXCR5 and provide help to B cells to produce antibodies (22–24, 41) These cells have been termed peripheral Tfh cells, although their relationship to LN pTfh cells is not firmly established. High expression of CCR7 on pTfh cells suggests that they may traffic to secondary lymphoid organs, possibly upon antigen encounter (24). New findings also support the concept that LN Tfh cells can exit into the circulation after becoming memory cells (42). However, the association of pTfh cells with HIV reservoirs in the context of cART and the susceptibility of pTfh cells to HIV infection are currently unknown. In this study, our findings imply that like LN Tfh cells, the pTfh cells in circulation may be enriched for HIV-infected cells and serve as a source of HIV persistence in patients on potent cART with suppressed plasma virus.

To understand the role of pTfh cells in HIV infection, we first analyzed the HIV permissiveness of pTfh cells and non-pTfh cells using sort-purified cells subsets from healthy HIV-negative volunteers by spinoculation of a GFP-expressing molecular clone of HIV (HIV-1 NL4-3/Ba-L). Our data indicate that PD1+pTfh cells harbor more virus than PD1neg pTfh cells or PD1+ non-pTfh cells among virally infected cells, as more than >70% of infected cells were PD1+ in the pTfh compartment. This observation is in agreement with previous findings of HIV-1 DNA in PD1hi TCM cells (10), which most likely represent the pTfh subset within the CD4 TCM cells. Taken together, our results support the concept that PD1+ pTfh cells constitute a circulating counterpart of LN-Tfh cells and provide valuable insight into the size of HIV reservoirs. Interestingly, susceptibility to HIV-1 in pTfh cells dominated irrespective of the coreceptor expression pattern, as non-pTfh cells showed higher CCR5 expression upon activation than pTfh cells. The permissiveness of these cells to become infected after overnight rest followed by spinoculation with HIV was borne out by the expression of GFP upon subsequent anti-CD3/anti-CD28 activation. These findings provide evidence for the potential role of pTfh cells as HIV reservoirs.

To substantiate the findings of HIV permissiveness in cells of healthy HIV-negative volunteers, we examined the pTfh cells of patients on cART by different approaches. First, we analyzed the total HIV DNA and 2LTR circles in purified pTfh cells and non-pTfh cells isolated from the CD4 TCM subset. 2LTR circular forms of HIV-1 are surrogate markers for recently infected cells due to their labile nature. Measurement of these products of abortive infection provides the means to gauge the level of ongoing infection and the types of cells that are infected in patients on suppressive therapy (10, 43). Although pTfh and non-pTfh cells showed similar levels of HIV DNA and 2LTR circles before cART, a significant decrease in 2LTR circles was observed at week 48 in both cell subsets even though total HIV DNA remained unchanged. Failure of HIV DNA to decrease in 12 months post-cART in pTfh and non-pTfh cells of chronically infected patients is not surprising. It is well known that the rate of decay of cell-associated HIV DNA is fastest in patients initiating treatment very early during the acute infection, and even in these situations the decay can take up to 8 months following cART initiation (44–46). In our study, all patients were chronically HIV infected, and it is likely that HIV DNA decay takes longer than 48 weeks on cART. The fast first-phase decay of viral DNA could result from the clearance of activated and productively infected TEM and TTM CD4 T cells (47) rather than the less activated long-living TCM cells (46, 47). Further, TEM and TTM CD4 T cells have shorter half-lives and are infected earlier than naive and TCM cells due to their higher level of immune activation and coreceptor expression. In fact, HIV DNA levels in total CD8-depleted PBMC at week 48 were significantly (P = 0.017) lower than pre-ART levels (Fig. 7A). As the majority of HIV DNA represents defective or mutated non-replication-competent virus (48), it is less relevant than 2LTR circles as an indicator of replicating virus (37, 38, 49, 50). The higher frequencies of 2LTR circles in pTfh cells than in non-pTfh cells at week 48 supports the concept that the pTfh cells are more supportive of HIV replication than non-pTfh or total CD4 TCM cells.

To obtain further proof for the role of pTfh cells as potential HIV reservoirs, we assessed whether HIV gag protein could be expressed in CD8-depleted PBMC with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation as a potential measure of inducible virus in patient cells (35, 36, 51). Using this assay, we could clearly identify PD1+ pTfh cells as the subset with the highest frequencies of HIV p24 protein before cART that underwent substantial reduction at 48 weeks on cART. The preferential expression of HIV-p24 in PD1+ pTfh cells substantiates the role of these cells as reservoirs based on prior studies of LN Tfh (12) and peripheral TCM (9, 10) in which PD1 expression was associated with HIV reservoirs (10). Our data support the concept that in circulating CD4 TCM cells, the pTfh cells are a major cellular subset for virus persistence in HIV-infected patients on potent cART. This observation underscores the importance of analyzing different subsets of CD4 TCM cells to identify and quantify the breadth and magnitude of HIV reservoirs in peripheral blood.

In the current study, cell limitation did not permit performing a quantitative viral outgrowth assay (QVOA) on resting CD4 T cells, which is the “gold standard” for HIV reservoir analysis. However, it is reasonable to consider the inducible HIV p24 in circulating CD4 TCM cells as being indicative of active virus transcription in cART-experienced patients. A potential argument against the relevance of the HIV p24 assay result as a measure of replication-competent HIV reservoir could be that frequencies of cells with inducible HIV p24 were higher than numbers of latently infected cells detected in the viral outgrowth assay (1 per million PBMC or less after a single round of activation). However, there is increasing evidence that the latent pool is much larger and at least 5-fold greater even in the QVOA after multiple rounds of stimulation (52, 53). Moreover, the subset analysis of pTfh cells within CD4 TCM cells likely enriched latent and active reservoirs that were expressed as inducible HIV gag p24 following in vitro cellular activation with minimal contribution of replication-incompetent viruses harboring lethal mutations. We contend that the inducible HIV p24 flow cytometry assay could be especially useful for monitoring HIV reservoirs in minor cell populations in circulating PBMC in situations where cell numbers are limiting, e.g., in young infants.

The state of T cell activation influenced HIV persistence, as suggested by the direct relationship of the frequencies of activated CD4 T cells with pTfh cells expressing 2LTR circles as well as inducible HIV p24 pre-ART and with 2LTR circle-expressing cells at week 48 post-ART. Activated CD8 T cells also correlated with HIV 2LTR circles in pTfh cells at entry. These findings are consistent with previous studies of raltegravir intensification in which HIV 2LTR circles were correlated with CD8 T cell immune activation in patients with undetectable plasma HIV RNA levels (50, 54). In these studies, however, CD4 T cell activation was not investigated, which may be more important in the context of HIV reservoirs. The data suggest that a generalized state of immune activation and in particular activation of pTfh cells makes these cells targets for HIV infection and HIV persistence despite cART.

We conclude that pTfh cells in circulation are highly permissive for HIV and that within TCM CD4 T cells, pTfh cells, in particular PD1+ pTfh cells, constitute HIV reservoirs in cART-treated patients. The TCM nature of pTfh cells could allow them to persist within total memory pool and contribute to HIV latency (10, 55). The inducible HIVp24 assay is simple to perform, with high degree of precision which could screen for HIV reservoirs and complement existing reservoir assays for HIV. Whether pTfh cells become infected via traffic through lymph nodes is unknown but is a possibility, given the functional and partial phenotypic similarity of pTfh with LN-Tfh. Evaluation of this subset could be of value in assessing reservoir size in clinical approaches for eliminating HIV reservoirs (56).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Laboratory Sciences Core of the CFAR and Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center for facilitating conduct of the flow cytometry studies. We also acknowledge AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH for providing the saquinavir and raltegravir for the experiments.

This study was supported by the University of Miami Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) via a CFAR developmental award to Suresh Pallikkuth and Laboratory Sciences Core of the CFAR to Savita Pahwa (National Institutes of Health, P30AI073961) and NIH R56 (R56AI106718) to Savita Pahwa. The CFAR program at the NIH includes the following cofunding and participating institutes and centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, FIC, and OAR.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

We do not have any financial, consultant or institutional conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perelson AS, Essunger P, Cao Y, Vesanen M, Hurley A, Saksela K, Markowitz M, Ho DD. 1997. Decay characteristics of HIV-1-infected compartments during combination therapy. Nature 387:188–191. doi: 10.1038/387188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perelson AS, Neumann AU, Markowitz M, Leonard JM, Ho DD. 1996. HIV-1 dynamics in vivo: virion clearance rate, infected cell life-span, and viral generation time. Science 271:1582–1586. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer S, Maldarelli F, Wiegand A, Bernstein B, Hanna GJ, Brun SC, Kempf DJ, Mellors JW, Coffin JM, King MS. 2008. Low-level viremia persists for at least 7 years in patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:3879–3884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800050105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dinoso JB, Kim SY, Wiegand AM, Palmer SE, Gange SJ, Cranmer L, O'Shea A, Callender M, Spivak A, Brennan T, Kearney MF, Proschan MA, Mican JM, Rehm CA, Coffin JM, Mellors JW, Siliciano RF, Maldarelli F. 2009. Treatment intensification does not reduce residual HIV-1 viremia in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:9403–9408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903107106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi RT, Coombs RW, Chan ES, Bosch RJ, Zheng L, Margolis DM, Read S, Kallungal B, Chang M, Goecker EA, Wiegand A, Kearney M, Jacobson JM, D'Aquila R, Lederman MM, Mellors JW, Eron JJ. 2012. No effect of raltegravir intensification on viral replication markers in the blood of HIV-1-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 59:229–235. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823fd1f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMahon D, Jones J, Wiegand A, Gange SJ, Kearney M, Palmer S, McNulty S, Metcalf JA, Acosta E, Rehm C, Coffin JM, Mellors JW, Maldarelli F. 2010. Short-course raltegravir intensification does not reduce persistent low-level viremia in patients with HIV-1 suppression during receipt of combination antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 50:912–919. doi: 10.1086/650749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun TW, Fauci AS. 2012. HIV reservoirs: pathogenesis and obstacles to viral eradication and cure. AIDS 26:1261–1268. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328353f3f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MZ, Wightman F, Lewin SR. 2012. HIV reservoirs and strategies for eradication. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 9:5–15. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chomont N, DaFonseca S, Vandergeeten C, Ancuta P, Sekaly RP. 2011. Maintenance of CD4+ T-cell memory and HIV persistence: keeping memory, keeping HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 6:30–36. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283413775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chomont N, El-Far M, Ancuta P, Trautmann L, Procopio FA, Yassine-Diab B, Boucher G, Boulassel MR, Ghattas G, Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Hill BJ, Douek DC, Routy JP, Haddad EK, Sekaly RP. 2009. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat Med 15:893–900. doi: 10.1038/nm.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buzon MJ, Sun H, Li C, Shaw A, Seiss K, Ouyang Z, Martin-Gayo E, Leng J, Henrich TJ, Li JZ, Pereyra F, Zurakowski R, Walker BD, Rosenberg ES, Yu XG, Lichterfeld M. 2014. HIV-1 persistence in CD4+ T cells with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med 20:139–142. doi: 10.1038/nm.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perreau M, Savoye AL, De Crignis E, Corpataux JM, Cubas R, Haddad EK, De Leval L, Graziosi C, Pantaleo G. 2013. Follicular helper T cells serve as the major CD4 T cell compartment for HIV-1 infection, replication, and production. J Exp Med 210:143–156. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinuesa CG. 2012. HIV and T follicular helper cells: a dangerous relationship. J Clin Invest 122:3059–3062. doi: 10.1172/JCI65175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindqvist M, van Lunzen J, Soghoian DZ, Kuhl BD, Ranasinghe S, Kranias G, Flanders MD, Cutler S, Yudanin N, Muller MI, Davis I, Farber D, Hartjen P, Haag F, Alter G, Schulze zur Wiesch J, Streeck H. 2012. Expansion of HIV-specific T follicular helper cells in chronic HIV infection. J Clin Invest 122:3271–3280. doi: 10.1172/JCI64314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenchley JM, Vinton C, Tabb B, Hao XP, Connick E, Paiardini M, Lifson JD, Silvestri G, Estes JD. 2012. Differential infection patterns of CD4+ T cells and lymphoid tissue viral burden distinguish progressive and nonprogressive lentiviral infections. Blood 120:4172–4181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-437608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukazawa Y, Park H, Cameron MJ, Lefebvre F, Lum R, Coombes N, Mahyari E, Hagen SI, Bae JY, Reyes MD III, Swanson T, Legasse AW, Sylwester A, Hansen SG, Smith AT, Stafova P, Shoemaker R, Li Y, Oswald K, Axthelm MK, McDermott A, Ferrari G, Montefiori DC, Edlefsen PT, Piatak M Jr, Lifson JD, Sekaly RP, Picker LJ. 2012. Lymph node T cell responses predict the efficacy of live attenuated SIV vaccines. Nat Med 18:1673–1681. doi: 10.1038/nm.2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klatt NR, Vinton CL, Lynch RM, Canary LA, Ho J, Darrah PA, Estes JD, Seder RA, Moir SL, Brenchley JM. 2011. SIV infection of rhesus macaques results in dysfunctional T- and B-cell responses to neo and recall Leishmania major vaccination. Blood 118:5803–5812. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-365874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrovas C, Yamamoto T, Gerner MY, Boswell KL, Wloka K, Smith EC, Ambrozak DR, Sandler NG, Timmer KJ, Sun X, Pan L, Poholek A, Rao SS, Brenchley JM, Alam SM, Tomaras GD, Roederer M, Douek DC, Seder RA, Germain RN, Haddad EK, Koup RA. 2012. CD4 T follicular helper cell dynamics during SIV infection. J Clin Invest 122:3281–3294. doi: 10.1172/JCI63039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukazawa Y, Lum R, Okoye AA, Park H, Matsuda K, Bae JY, Hagen SI, Shoemaker R, Deleage C, Lucero C, Morcock D, Swanson T, Legasse AW, Axthelm MK, Hesselgesser J, Geleziunas R, Hirsch VM, Edlefsen PT, Piatak M Jr, Estes JD, Lifson JD, Picker LJ. 2015. B cell follicle sanctuary permits persistent productive simian immunodeficiency virus infection in elite controllers. Nat Med 21:132–139. doi: 10.1038/nm.3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cameron PU, Saleh S, Sallmann G, Solomon A, Wightman F, Evans VA, Boucher G, Haddad EK, Sekaly RP, Harman AN, Anderson JL, Jones KL, Mak J, Cunningham AL, Jaworowski A, Lewin SR. 2010. Establishment of HIV-1 latency in resting CD4+ T cells depends on chemokine-induced changes in the actin cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:16934–16939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002894107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saleh S, Solomon A, Wightman F, Xhilaga M, Cameron PU, Lewin SR. 2007. CCR7 ligands CCL19 and CCL21 increase permissiveness of resting memory CD4+ T cells to HIV-1 infection: a novel model of HIV-1 latency. Blood 110:4161–4164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-097907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chevalier N, Jarrossay D, Ho E, Avery DT, Ma CS, Yu D, Sallusto F, Tangye SG, Mackay CR. 2011. CXCR5 expressing human central memory CD4 T cells and their relevance for humoral immune responses. J Immunol 186:5556–5568. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morita R, Schmitt N, Bentebibel SE, Ranganathan R, Bourdery L, Zurawski G, Foucat E, Dullaers M, Oh S, Sabzghabaei N, Lavecchio EM, Punaro M, Pascual V, Banchereau J, Ueno H. 2011. Human blood CXCR5(+)CD4(+) T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity 34:108–121. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinuesa CG, Cook MC. 2011. Blood relatives of follicular helper T cells. Immunity 34:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crotty S. 2011. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu Rev Immunol 29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sage PT, Alvarez D, Godec J, von Andrian UH, Sharpe AH. 2014. Circulating T follicular regulatory and helper cells have memory-like properties. J Clin Invest 124:5191–5204. doi: 10.1172/JCI76861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai LM, Yu D. 2014. Follicular helper T-cell memory: establishing new frontiers during antibody response. Immunol Cell Biol 92:57–63. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pallikkuth S, Fischl MA, Pahwa S. 2013. Combination antiretroviral therapy with raltegravir leads to rapid immunologic reconstitution in treatment-naive patients with chronic HIV infection. J Infect Dis 208:1613–1623. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.HIV AIDS Network Coordination (hanc). 3 October 2011. Cross-network PBMC processing SOP v4.0. https://www.hanc.info/labs/Documents/HANC-LAB-0001_v4.0_2011-10-03_PBMC%20SOP.pdf Accessed 5 March 2012.

- 30.Boyum A. 1968. Isolation of mononuclear cells and granulocytes from human blood. Isolation of monuclear cells by one centrifugation, and of granulocytes by combining centrifugation and sedimentation at 1 g. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl 97:77–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta S, Termini JM, Niu L, Kanagavelu SK, Schmidtmayerova H, Snarsky V, Kornbluth RS, Stone GW. 2011. EBV LMP1, a viral mimic of CD40, activates dendritic cells and functions as a molecular adjuvant when incorporated into an HIV vaccine. J Leukoc Biol 90:389–398. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0211068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maecker HT, Trotter J. 2006. Flow cytometry controls, instrument setup, and the determination of positivity. Cytometry A 69:1037–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perfetto SP, Ambrozak D, Nguyen R, Chattopadhyay P, Roederer M. 2006. Quality assurance for polychromatic flow cytometry. Nat Protoc 1:1522–1530. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lassen KG, Hebbeler AM, Bhattacharyya D, Lobritz MA, Greene WC. 2012. A flexible model of HIV-1 latency permitting evaluation of many primary CD4 T-cell reservoirs. PLoS One 7:e30176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mascola JR, Louder MK, Winter C, Prabhakara R, De Rosa SC, Douek DC, Hill BJ, Gabuzda D, Roederer M. 2002. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralization measured by flow cytometric quantitation of single-round infection of primary human T cells. J Virol 76:4810–4821. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4810-4821.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saleh S, Wightman F, Ramanayake S, Alexander M, Kumar N, Khoury G, Pereira C, Purcell D, Cameron PU, Lewin SR. 2011. Expression and reactivation of HIV in a chemokine induced model of HIV latency in primary resting CD4+ T cells. Retrovirology 8:80. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharkey M, Babic DZ, Greenough T, Gulick R, Kuritzkes DR, Stevenson M. 2011. Episomal viral cDNAs identify a reservoir that fuels viral rebound after treatment interruption and that contributes to treatment failure. PLoS Pathog 7:e1001303. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharkey ME, Teo I, Greenough T, Sharova N, Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL, Bucy RP, Kostrikis LG, Haase A, Veryard C, Davaro RE, Cheeseman SH, Daly JS, Bova C, Ellison RT III, Mady B, Lai KK, Moyle G, Nelson M, Gazzard B, Shaunak S, Stevenson M. 2000. Persistence of episomal HIV-1 infection intermediates in patients on highly active anti-retroviral therapy. Nat Med 6:76–81. doi: 10.1038/71569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fazilleau N, Mark L, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. 2009. Follicular helper T cells: lineage and location. Immunity 30:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu Y, Weatherall C, Bailey M, Alcantara S, De Rose R, Estaquier J, Wilson K, Suzuki K, Corbeil J, Cooper DA, Kent SJ, Kelleher AD, Zaunders J. 2013. Simian immunodeficiency virus infects follicular helper CD4 T cells in lymphoid tissues during pathogenic infection of pigtail macaques. J Virol 87:3760–3773. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02497-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pallikkuth S, Parmigiani A, Silva SY, George VK, Fischl M, Pahwa R, Pahwa S. 2012. Impaired peripheral blood T-follicular helper cell function in HIV-infected non-responders to the 2009 H1N1/09 vaccine. Blood 120:985–993. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-396648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suan D, Nguyen A, Moran I, Bourne K, Hermes JR, Arshi M, Hampton HR, Tomura M, Miwa Y, Kelleher AD, Kaplan W, Deenick EK, Tangye SG, Brink R, Chtanova T, Phan TG. 2015. T follicular helper cells have distinct modes of migration and molecular signatures in naive and memory immune responses. Immunity 42:704–718. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharkey M, Triques K, Kuritzkes DR, Stevenson M. 2005. In vivo evidence for instability of episomal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cDNA. J Virol 79:5203–5210. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.5203-5210.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viard JP, Burgard M, Hubert JB, Aaron L, Rabian C, Pertuiset N, Lourenco M, Rothschild C, Rouzioux C. 2004. Impact of 5 years of maximally successful highly active antiretroviral therapy on CD4 cell count and HIV-1 DNA level. AIDS 18:45–49. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hocqueloux L, Avettand-Fenoel V, Jacquot S, Prazuck T, Legac E, Melard A, Niang M, Mille C, Le Moal G, Viard JP, Rouzioux C. 2013. Long-term antiretroviral therapy initiated during primary HIV-1 infection is key to achieving both low HIV reservoirs and normal T cell counts. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1169–1178. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laanani M, Ghosn J, Essat A, Melard A, Seng R, Gousset M, Panjo H, Mortier E, Girard PM, Goujard C, Meyer L, Rouzioux C. 2015. Impact of the timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy during primary HIV-1 infection on the decay of cell-associated HIV-DNA. Clin Infect Dis 60:1715–1721. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chéret A, Bacchus C, Mélard A, Nembot G, Blanc C, Samri A, Avettand-Fenoël V, SaezCirion A, Autran B, Rouzioux C, OPTIPRIM ANRS-147 Study Group . 2014. Early HAART in primary HIV infection protects TCD4 central memory cells and can induce HIV remission, poster 398. In 21st Conf Retroviruses Opportunistic Infect (CROI), Boston, MA, 3 to 6 March 2014 http://croi2014.org/sites/default/files/uploads/CROI2014_Final_Abstracts.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ho YC, Shan L, Hosmane NN, Wang J, Laskey SB, Rosenbloom DI, Lai J, Blankson JN, Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF. 2013. Replication-competent noninduced proviruses in the latent reservoir increase barrier to HIV-1 cure. Cell 155:540–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buzón MJ, Massanella M, Llibre JM, Esteve A, Dahl V, Puertas MC, Gatell JM, Domingo P, Paredes R, Sharkey M, Palmer S, Stevenson M, Clotet B, Blanco J, Martinez-Picado J. 2010. HIV-1 replication and immune dynamics are affected by raltegravir intensification of HAART-suppressed subjects. Nat Med 16:460–465. doi: 10.1038/nm.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Llibre JM, Buzon MJ, Massanella M, Esteve A, Dahl V, Puertas MC, Domingo P, Gatell JM, Larrouse M, Gutierrez M, Palmer S, Stevenson M, Blanco J, Martinez-Picado J, Clotet B. 2012. Treatment intensification with raltegravir in subjects with sustained HIV-1 viraemia suppression: a randomized 48-week study. Antivir Ther 17:355–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shete A, Thakar M, Singh DP, Gangakhedkar R, Gaikwad A, Pawar J, Paranjape R. 2012. Short communication: HIV antigen-specific reactivation of HIV infection from cellular reservoirs: implications in the settings of therapeutic vaccinations. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 28:835–843. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruner KM, Hosmane NN, Siliciano RF. 2015. Towards an HIV-1 cure: measuring the latent reservoir. Trends Microbiol 23:192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenbloom DI, Elliott O, Hill AL, Henrich TJ, Siliciano JM, Siliciano RF. 2015. Designing and interpreting limiting dilution assays: general principles and applications to the latent reservoir for human immunodeficiency virus-1. Open Forum Infect Dis 2:ofv123. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vallejo A, Gutierrez C, Hernandez-Novoa B, Diaz L, Madrid N, Abad-Fernandez M, Dronda F, Perez-Elias MJ, Zamora J, Munoz E, Munoz-Fernandez MA, Moreno S. 2012. The effect of intensification with raltegravir on the HIV-1 reservoir of latently infected memory CD4 T cells in suppressed patients. AIDS 26:1885–1894. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283584521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lambotte O, Demoustier A, de Goer MG, Wallon C, Gasnault J, Goujard C, Delfraissy JF, Taoufik Y. 2002. Persistence of replication-competent HIV in both memory and naive CD4 T cell subsets in patients on prolonged and effective HAART. AIDS 16:2151–2157. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211080-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DaFonseca S, Chomont N, El Far M, Boulassel R, Routy J, Sékaly R. 2010. Purging the HIV-1 reservoir through the disruption of the PD-1 pathway. J Int AIDS Soc 13:O15. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-S3-O15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]