Abstract

Background

Incorporation of exon 11 of the insulin receptor gene is both developmentally and hormonally-regulated. Previously, we have shown the presence of enhancer and silencer elements that modulate the incorporation of the small 36-nucleotide exon. In this study, we investigated the role of inherent splice site strength in the alternative splicing decision and whether recognition of the splice sites is the major determinant of exon incorporation.

Results

We found that mutation of the flanking sub-optimal splice sites to consensus sequences caused the exon to be constitutively spliced in-vivo. These findings are consistent with the exon-definition model for splicing. In-vitro splicing of RNA templates containing exon 11 and portions of the upstream intron recapitulated the regulation seen in-vivo. Unexpectedly, we found that the splice sites are occupied and spliceosomal complex A was assembled on all templates in-vitro irrespective of splicing efficiency.

Conclusion

These findings demonstrate that the exon-definition model explains alternative splicing of exon 11 in the IR gene in-vivo but not in-vitro. The in-vitro results suggest that the regulation occurs at a later step in spliceosome assembly on this exon.

Background

The human insulin receptor (IR) is encoded by a single gene that is located on chromosome 19 and composed of 22 exons. The mature IR exists as two isoforms, designated A and B, which result from alternative splicing of the primary transcript. The A isoform lacking exon 11 binds both insulin and IGF-II with high affinity and is expressed ubiquitously; the B isoform containing exon 11 only binds insulin and is expressed predominantly in liver, muscle, adipocytes, and kidney [1,2]. The alternatively spliced exon 11 encodes a 12-amino acid segment (residues 717–728) of the  subunit of receptor that disrupts binding to IGF-II [3]. Inclusion of this exon is developmentally and hormonally-regulated and is altered in a number of disease states, such as type II diabetes and myotonic dystrophy, that are associated with insulin resistance [4-10]. The dysregulation of the alternative splicing of the IR may have important consequences for insulin-sensitivity and responsiveness. In previous studies, we have investigated the regulation of splicing of this exon in-vivo using a model minigene system containing exons 10, 11, and 12 and parts of the intervening introns [11]. Recognition of the exon appears to be rate-limiting as partially spliced RNAs were identified that lacked intron 10 but retained intron 11, but none were observed lacking only intron 11. We furthermore identified both enhancer and silencer elements in the precursor RNA that modulated incorporation of exon 11.

subunit of receptor that disrupts binding to IGF-II [3]. Inclusion of this exon is developmentally and hormonally-regulated and is altered in a number of disease states, such as type II diabetes and myotonic dystrophy, that are associated with insulin resistance [4-10]. The dysregulation of the alternative splicing of the IR may have important consequences for insulin-sensitivity and responsiveness. In previous studies, we have investigated the regulation of splicing of this exon in-vivo using a model minigene system containing exons 10, 11, and 12 and parts of the intervening introns [11]. Recognition of the exon appears to be rate-limiting as partially spliced RNAs were identified that lacked intron 10 but retained intron 11, but none were observed lacking only intron 11. We furthermore identified both enhancer and silencer elements in the precursor RNA that modulated incorporation of exon 11.

Splicing of pre-mRNA depends on the presence of relatively short RNA sequence elements, the 3' splice site, the 5' splice site, and the branch point sequence (reviewed in ref [12]). Removal of the intron occurs via two transesterification reactions; the first occurring between the 5' splice site and the 2'-OH of the branch point adenine, the second occurring between the 3'-OH of the 5' exon and the 3' exon. The sites are aligned for accurate excision by a complex network of RNA and protein interactions involving both splice sites and the branch point sequence in a large complex called the spliceosome. Assembly of the spliceosome begins with recognition of the 5' splice site by the U1 snRNP by base pairing. U2 snRNP is recruited to the branch point sequence by the accessory factor U2AF [13-15]. This factor is a heterodimer of a 65 kDa subunit that recognizes a polypyrimidine tract and a 35 kDa subunit that recognizes the 3' splice site and promotes binding of U2AF-65 [16-18]. Binding of U2AF to the 3' splice site is further stabilized by the branch point binding protein BBP/SF1 that also interacts with the Prp40 subunit of the U1 snRNP [19-21]. The complex containing the pre-RNA, and the U1 and U2 snRNPs is called the pre-spliceosomal complex or complex A in mammals. This complex then recruits the U4/U5/U6 tri-snRNP to form complex B, and the spliceosome undergoes a number of rearrangements to create the catalytically active splicing complex C. Each of the steps in assembly is facilitated by numerous extrinsic factors that may or may not become part of the final spliceosome [22].

Alternative cassette exons often contain splice sites that are weak matches to the consensus sequence and mutation of the sites to the consensus in many cases causes the exon to be spliced constitutively. Recognition of these splice sites is inherently poor but can be modulated by cis-acting elements in the RNA that bind trans-acting splicing factors (reviewed in ref [23]). These elements can either have a positive (splicing enhancers) or negative (splicing silencers) effect on splicing. Differences in the expression level, or activity of the trans-acting factors modulates the recognition of the alternative exon and leads to developmental or tissue specific differences in splicing. One model for enhancer function, the U2AF recruitment model, involves the stabilization of the interaction of the subunits of U2AF with the branch point sequence and 3' splice site. SR proteins have been shown to increase cross-linking of U2AF-65 to the 3' splice site by interacting with the 35 kDa subunit U2AF-35 [24]. SR proteins have also been shown to interact with the U1-70K protein that is a component of the U1-snRNP [25,26]. These interactions have led to the proposal that SR proteins bridge splice sites across introns, or exons, by binding to components of both the 5' and 3' splice sites. A number of studies have shown that the ability of SR proteins to bind to exonic enhancers correlates with their ability to activate splicing from weak splice sites, the inference being that the SR proteins were recruiting factors to the splice sites [27-30]. This has lead to the notion that alternative splicing is regulated at the level of splice site recognition. Consistent with this idea, a number of splicing factors have been shown to act as silencers by blocking access to splice sites and mutation of constitutive splice sites abrogates recognition of the sites [31,32]. In this study, we tested the exon-definition model on exon 11 of the IR gene by mutating the splice sites flanking the exon. We also investigated the recognition of these splice sites by the splicing apparatus in-vitro and found that pre-spliceosmal splicing complexes are formed on all sites irrespective of splicing efficiency.

Results

Mutation of splice sites surrounding exon 11 alters its incorporation into mRNA

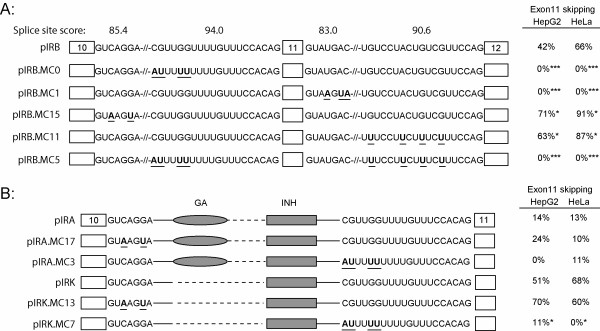

An inspection of the 5' splice site sequences of both exons 10 and 11 highlighted a number of differences from the consensus sequence that is complementary to the U1 snRNA. Analysis of splice site strength using the Shapiro-Senapathy method gave scores of 85.4 and 83.0 (out of 100) for the two 5' splice sites (Fig. 1A). This suggested to us that the sites encompassing exon 11 were likely to be inefficient. Splice sites at the 3' end of exons are less defined but the length of the poly-pyrimidine tract is often an indication of splice site strength. Both 3' splice sites in the IR minigene contain a number of purine nucleotide insertions in the polypyrimidine tract, but still scored 94.0 and 90.6. The scores suggested that these sites would be active splice sites, but we wanted to test whether they were less than optimal. Each 5' splice site was mutated to the consensus sequence and the purine insertions in the 3' splice sites were mutated to thymidines thus lengthening the tracts.

Figure 1.

Skipping of exon 11 requires sub-optimal splice sites. Exons 10, 11, and 12 and the sequences of the splice sites at the ends of the introns are shown. Panel A: The 5' splice sites of exon 10 and exon 11 are 5/7 and 4/7 matches to the consensus sequence, respectively. The splice site scores (out of 100) are indicated above each site. These sites were altered to match the consensus sequence in the parental IR minigene (pIRB) that contains 2.3 Kb of intron 10 and 360 bp of intron 11 giving minigenes pIRB.MC15 and pIRB.MC1. The 3' splice sites of exon 11 and exon 12 contain a number of purine residues interspersed in the polypyrimidine tracts. These residues were mutated to thymidines to strengthen each 3' splice site giving minigenes pIRB.MC0 and pIRB.MC11. Mutated residues are shown in bold and underlined. The intervening sequence is omitted and indicated by the slashes. The minigenes were transfected into HepG2 and HeLa cells. RNA was extracted and mRNA subjected to reverse transcription and amplification by PCR. The columns to the right show the percentage of skipping of exon 11 in either cell line. Results are the mean of four independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance versus the parental minigene pIRB (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001). Panel B: The same mutations were introduced into the splice sites of intron 10 in minigenes containing internal deletions of intron 10. Minigene pIRA contains the purine-rich enhancer (GA) and the inhibitor (INH), minigene pIRK only contains the inhibitor (INH). Sequences of the 5' and 3' splice sites of intron 10 are shown. Intervening sequence is indicated by dashed lines. Both pIRA and pIRK contain the identical intron 11 and exon 12 sequences as pIRB in Panel A but these sequences are omitted for clarity. These minigenes were transfected into HepG2 and HeLa cells as above. The percentage of skipping of exon 11 is given in the columns on the right. Results are the mean of four independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance versus the minigene with natural splice sites * p < 0.05).

The mutant minigenes were tested by transfection into HepG2 and HeLa cells. RNA was extracted and subjected to reverse-transcription and PCR using primers described previously [11]. To ensure that only mature mRNA was analyzed, RNA was captured on oligo-dT before reverse transcription. The parental minigene containing the 2.3 Kb intron 10 showed 42% skipping of exon 11 in HepG2 cells and 66% in HeLa cells (pIRB, Fig. 1A). Thus, exon 11 in the minigene is recognized more efficiently in HepG2 cells than HeLa cells, which is consistent with the known splicing of the endogenous IR gene in these cells. We have previously shown that mutation of a single G residue at position -10 in the pyrimidine tract did not alter exon incorporation but increasing the length of the polypyrimidine tract caused the exon to be recognized constitutively in both HepG2 and HeLa cells (pIRB.MC0). Similarly, mutation of the 5' splice site on exon 11 to the consensus caused the exon to be spliced constitutively (pIRB.MC1, Fig. 1A). Therefore, strengthening either splice site flanking exon 11 caused the exon to be recognized more efficiently. Conversely, mutation of the 5' splice site on exon 10 or increasing the length of the polypyrimidine tract on exon 12 caused exon skipping to increase in both cell types (pIRB.MC15 and pIRB.MC11, respectively). Increasing the strength of the distal 3' splice site in the presence of a strong proximal site did not cause skipping of exon 11 (pIRB.MC5), however, indicating that exon skipping is only observed in the presence of non-consensus splice sites on exon 11.

These mutations were also tested in minigenes containing internal deletions in intron 10 as we had previously demonstrated the presence of a purine-rich enhancer at the 5' end and a silencer at the 3' end of intron 10, respectively. Minigene pIRA contains both the enhancer and silencer but the large internal deletion in intron 10 causes the juxtaposition of the purine-rich enhancer with the 3' splice site causing an increase in exon inclusion (Fig. 1B, pIRA). Mutation of neither the 3' splice site of exon 11 nor the 5' splice site in exon 10 in this background has a statistically significant effect on exon skipping, as the exon is already spliced efficiently due to the enhancer (Fig. 1B, pIRA.MC17 & pIRA.MC3). Removal of the purine-rich enhancer from minigene pIRA, resulting in minigene pIRK, restores exon incorporation to levels comparable to the parental minigene pIRB and once again mutation of the 3' splice site caused the exon to be incorporated constitutively in both cells (Fig. 1B, pIRK.MC7).

Intron 10 of the IR gene is spliced efficiently in-vitro

To analyze the recognition of exon 11 directly, we developed an in-vitro splicing assay. We had previously demonstrated that splicing of intron 10 is the regulated step, so templates were created which contained exon 10, segments of intron 10, and exon 11 of the IR gene. These RNA templates (A, C, K, and L) were derived from minigenes pIRA, pIRC, pIRK and pIRL that show differential skipping of exon 11 when transfected into HepG2 and HeLa cells [11]. The intron in template A (255 nt) contains both the purine-rich enhancer and the inhibitor; template C (188 nt) contains the enhancer only, template K (151 nt) contains the inhibitor only, and template L (84 nt) contains neither (Fig. 2A). The presence of a 5' splice site on the 3' end of a RNA template has been shown to enhance splicing on other RNAs by facilitating exon-definition [33]. Consequently, splicing reactions were performed on templates lacking the terminal splice site, containing the 7-nucleotide natural splice site, or containing a 7-nucleotide consensus splice site. We were unable to obtain HepG2 nuclear extracts that were capable of supporting splicing. Consequently, all of the in-vitro splicing reactions were performed with HeLa extracts alone. The four template RNAs were incubated with 40% HeLa nuclear extract for 60 min, and the spliced RNAs extracted and separated on 5% sequencing gels (Fig. 2B). Lariat intermediates were identified by differential mobility on 8% gels (data not shown). Similar experiments with a two-exon template containing the downstream intron, or a three-exon template containing both introns 10 and 11 failed to splice under these conditions (data not shown), so subsequent experiments focused on splicing of the upstream intron 10.

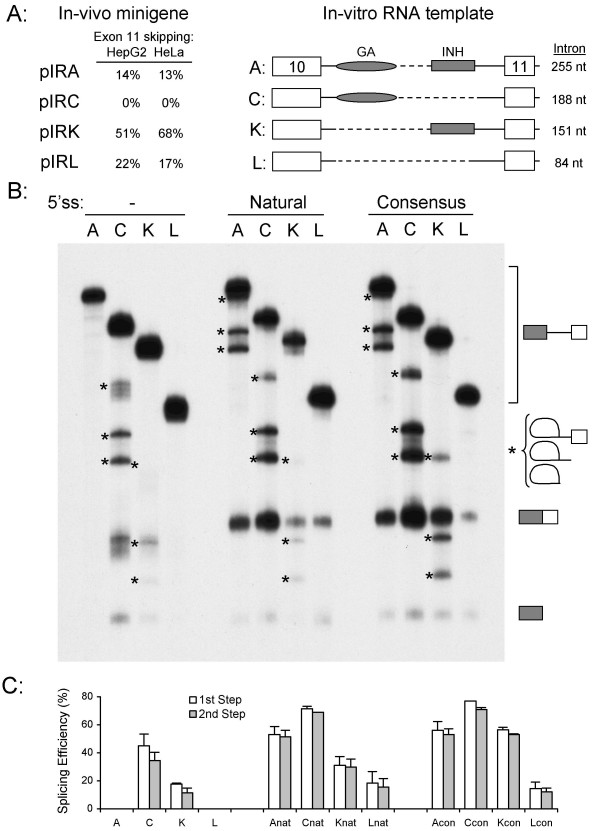

Figure 2.

In-vitro splicing of IR intron 10 templates. Panel A: Schematic of RNA templates used for in-vitro splicing. Left panel shows the percentage of skipping of exon 11 for four minigenes pIRA, pIRC, pIRK, and pIRL in HepG2 and HeLa cells in-vivo. Right panel shows the four templates generated by PCR amplification across exons 10 and 11 of the respective minigenes. The templates lacked the downstream intron and exon 12 that are present in the minigenes. The presence of the purine-rich enhancer (GA) and inhibitor (INH) are indicated, dashed lines represent deleted sequence. The size of the intron is shown. Panel B: Splicing of RNA templates either lacking the first seven nucleotides of intron 11 (left lanes), or containing the natural 5' splice site (center lanes) or a consensus 5' splice site (right lanes). All templates were incubated with 40% HeLa nuclear extract under splicing conditions for 60 min, the RNA extracted and separated on 5% sequencing gels. The RNA templates, spliced RNA (153 nt), and 5' exon (110 nt) are indicated by symbols on the right. Lariat intermediates were identified by differential mobility on 8% acrylamide gels and are indicated by asterisks. Panel C: Splicing efficiency was quantified by densitometric scanning of autoradiographs. The natural 5' splice site is represented by nat, the consensus 5' splice site by con. Second step efficiency was calculated from the ratio of spliced product to total RNA (spliced, 5' exon, and template, adjusted for labeling), first step efficiency was calculated from the ratio of spliced product plus 5' exon to total RNA. Values below the gel show the mean of three determinations and show the percent efficiency of each step for each template.

All four templates lacking the terminal 5' splice site were spliced inefficiently (Fig. 2B left lanes). Templates A and L are not spliced in the HeLa nuclear extract, and only very weak splicing was observed for template K. Three lariat intermediates, the free 5' exon, and the spliced product were only observed on template C, which contains the GA-enhancer and lacks the inhibitor. The spliced product and the uppermost lariat intermediate also showed exonucleolytic degradation. Inclusion of the natural splice site on the four templates increased the efficiency of splicing and generated splicing products 7-nucleotides longer (Fig. 2B center lanes). The increased splicing is consistent with the exon-definition model. There is also less degradation, which is consistent with the terminal splice site having a protective effect on RNA stability. The relative splicing efficiencies of these four templates mirrors the in-vivo results with the exception of template L. This is the smallest template and is spliced less efficiently in-vitro, although it is spliced efficiently in-vivo. This is most likely due to a size limitation with the in-vitro system, as introns smaller than 80 nucleotides are not spliced efficiently in HeLa extracts although they can be spliced in-vivo. Mutation of the natural splice site to the consensus further increased the efficiency of splicing on template K, but not on templates A, C, & L (Fig. 2B right lanes). Data from three experiments were combined to calculate the efficiency of splicing (step 1 and step 2) and the results are shown graphically (Fig. 2C). All of the regulation appears to be at the first step of splicing as first and second step splicing efficiencies are highly correlated.

Elimination of the splicing inhibitor from the template RNA caused an increase in splicing on all templates irrespective of the presence of the terminal 5' splice site (Fig. 2C compare templates A and C). This is consistent with the increase in exon 11 inclusion in minigenes pIRA and pIRC in-vivo in HepG2 and HeLa cells. Elimination of the purine-rich enhancer caused a decrease in intron splicing only on the template containing the natural 5' splice site from exon 11 (Fig. 2C compare templates Anat and Knat). This is consistent with the behavior of minigenes pIRA and pIRK in-vivo. The two templates A and K lacking the terminal 5' splice site are not spliced, and the presence of a consensus 5' splice site abrogates the effect of the enhancer (Fig. 2C compare A & K, Acon & Kcon, respectively). Mutation of this site to the consensus sequence caused the exon to be spliced constitutively in-vivo (Fig. 1B), thus the in-vitro splicing assay recapitulates the regulation seen in-vivo.

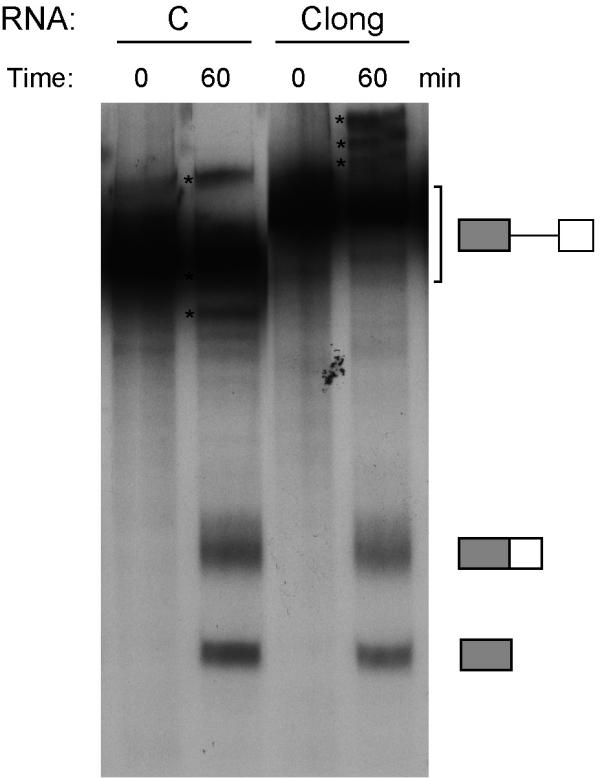

A simple explanation for the increased splicing efficiency with deletion of the splicing inhibitor in intron 10 (i.e. templates A & C) is that the splice site spacing is reduced, which might increase the possibility of intronic definition. To exclude this explanation, we constructed a template Clong that maintained the spacing of the splice sites but eliminated the splicing inhibitor sequence by including more sequence from the 5' end of the intron. The Clong and C templates were spliced with equal efficiency in the HeLa extract (Fig. 3), so we do not believe intron length alters splicing efficiency on these templates.

Figure 3.

Increasing intron length does not reduce splicing efficiency in-vitro. RNA templates were generated from minigene C and lacked the first seven nucleotides of intron 11. Clong contained an additional 67 nucleotides from the 5' end of intron 10 to maintain intron length at 255 nucleotides (see template A, Fig. 2). Both templates were incubated with 40% HeLa nuclear extract at 0°C or under splicing conditions for 60 min, the RNA extracted and separated on 8% sequencing gels. The RNA templates, spliced RNA (153 nt), and 5' exon (110 nt) are indicated by symbols on the right. Lariat intermediates are indicated by asterisks

Both the 5' and 3' splice sites are protected from RNaseH digestion in-vitro

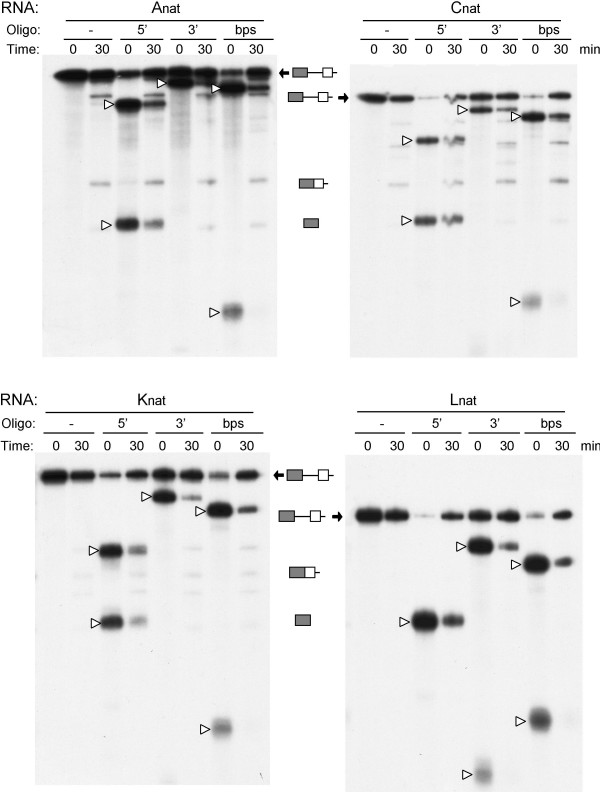

The exon-definition model for splicing regulation proposes that the inclusion of an exon in an mRNA is determined by the occupancy of the flanking 5' and 3' splice sites due to base-pairing interactions with the U1 and U2 snRNPs. We investigated whether the 5' and 3' splice sites were occupied on our insulin receptor templates using an RNase H protection assay [34]. The four IR templates, A, C, K, and L, containing the natural terminal 5' splice site were probed with three oligonucleotides, one targeting the 5' splice site of exon 10, another targeting the 3' splice site upstream of exon 11, and the third targeting the branch point sequence. The templates were incubated with HeLa nuclear extract on ice or at 30°C for 30 min before the addition of the oligonucleotides and RNase H. The cleaved RNAs were separated by gel-electrophoresis on 5% sequencing gels. The addition of RNase H alone did not result in cleavage of the template RNAs (Fig. 4, left lanes in each panel). Addition of RNase H plus any of the three oligonucleotides caused the appearance of two fragments on all four templates (Fig. 4). Incubation of the templates at 30°C for 30 min to allow the formation of splicing complexes, caused a decrease in the amount of cleaved RNA and a concomitant increase in the amount of un-cleaved RNA. Lariat intermediates and spliced products are also observed on templates A, C, and K following incubation at 30°C verifying that splicing had occurred. Thus, the splice sites on all four templates are protected under these conditions. Occupancy of these sites is to be expected as all templates are spliced, albeit with different efficiencies, when the templates contain terminal 5' splice sites (Fig. 2).

Figure 4.

Protection of the 5' and 3' splice sites and the branch point sequence. An RNaseH protection assay was used to probe occupancy of the splice sites on the IR templates. The four templates Anat, Cnat, Knat, and Lnat containing the natural terminal 5' splice site were incubated on ice or at 30°C for 30 min. Oligonucleotides complementary to the 5' splice site, the 3' splice site, or the branch point sequence (10 μM) were added followed by 2U RNaseH. Reactions were digested for 5 min at 37°C, the RNA extracted and separated on 5% sequencing gels. The time of incubation at 30°C is indicated above each panel along with the oligo added. Open arrowheads indicate RNase cleavage products for each oligonucleotide. RNase protection results in a decrease in cleavage products and an increase in uncleaved RNA. Spliced product and 5' exon are visible in some reactions that have been incubated at 30°C. The small fragment from cleavage of probes Anat, Cnat and Knat at the 3' splice site has run off the gel in this experiment. The two cleavage products from the 5' splice site oligo on template Lnat co-migrate.

Similar RNase H protection assays were performed on templates lacking the terminal 5' splice site or containing a consensus splice site. In these experiments we used the two oligonucleotides complementary to the 5' splice site or the branch point sequence. The 5' splice site oligonucleotide directed cleavage of all eight templates (Fig. 5A). Incubation of the reactions at 30°C for 30 min to allow formation of splicing complexes caused a decrease in the extent of cleavage on all templates. No intermediates or splicing products were observed on templates lacking the splice site, as these are not spliced efficiently at 30 min (Fig. 5A, left panel). Splicing products and lariat intermediates were observed for the templates containing consensus splice sites confirming that splicing had occurred (Fig. 5A, right panel). Similarly, the branch point sequence oligonucleotide directed cleavage of all templates, and protection was observed after incubation under splicing conditions (Fig. 5B). Here again, intermediates and splice products were only observed on the templates containing the consensus splice site (Fig. 5B, right panel).

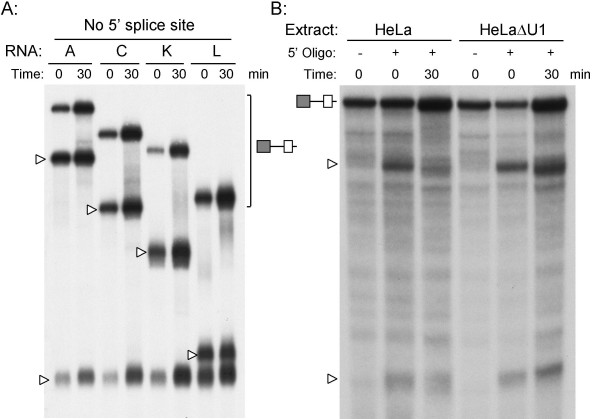

Figure 5.

Protection of the 5' splice site and branch point sequence of intron 10. The templates were derived from minigenes A, C, K, and L, and either lacked the terminal 5' splice site of exon 11 (A, C, K, & L, left panel) or contained a consensus terminal splice site (Acon, Ccon, Kcon, & Lcon, right panel). The templates were incubated on ice or at 30°C for 30 min. An oligonucleotide complementary to the 5' splice site of exon 10 was added followed by 2U RNase H. Reactions were digested for 5 min at 37°C, the RNA extracted and separated on 5% sequencing gels. The time of incubation at 30°C is indicated above each panel along with the template added. Panel A: RNase H protection assay using the oligonucleotide complementary to the 5' splice site of exon 10. Panel B: RNase H protection assay using the oligonucleotide complementary to the branch point sequence of intron 10. Open arrowheads indicate cleavage products from each template. Spliced product and 5' exon can be seen in the right panel as the templates with the consensus splice site are spliced efficiently.

To verify that the observed RNaseH protection was not due to non-specific protein binding to the RNA, an oligonucleotide to exon 10 upstream of the 5' splice site was used. This oligonucleotide caused efficient cleavage of four templates lacking the terminal splice site. Although the absolute recovery of RNAs varied, the ratio of cleaved to uncleaved RNA was not altered by incubation under splicing conditions at 30°C (Fig. 6A). Thus, this sequence is not protected from digestion by RNaseH. Furthermore, the initial step in spliceosomal assembly is recognition of the 5' splice site by the U1 snRNP. To verify that the observed protection at the 5' splice site is due to U1 snRNP binding, we performed RNaseH protection assays in HeLa nuclear extracts that had been depleted for U1 snRNP by RNaseH-mediated digestion of the U1 snRNA. No protection of the 5' splice site is observed in these extracts (Fig. 6B). Similar results were obtained by immuno-depleting extracts with an antibody to U1 70 K protein (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Lack of protection by an oligonucleotide complementary to exon 10. Panel A: RNase H protection assay was performed using an oligonucleotide complementary to exon 10. The templates were derived from minigenes A, C, K, and L, and lacked the terminal 5' splice site of exon 11. The templates were incubated on ice or at 30°C for 30 min. An oligonucleotide complementary to exon 10 was added followed by 2U RNase H. Reactions were digested for 5 min at 37°C, the RNA extracted and separated on 5% sequencing gels. The time of incubation at 30°C is indicated above each panel along with the template added. Open arrowheads indicate cleavage products from each template. The ratio of cleaved to uncleaved RNA is unaltered with this oligonucleotide. Panel B: the HeLa nuclear extract was pretreated with RNase H and an oligonucleotide complementary to the first 14 nucleotides of the U1 snRNA to deplete functional U1 snRNP. RNaseH protection assays were run as before using the oligonucleotide complementary to the 5' splice site using control (HeLa) or depleted (HeLaΔU1) extracts. Open arrowheads indicate cleavage products.

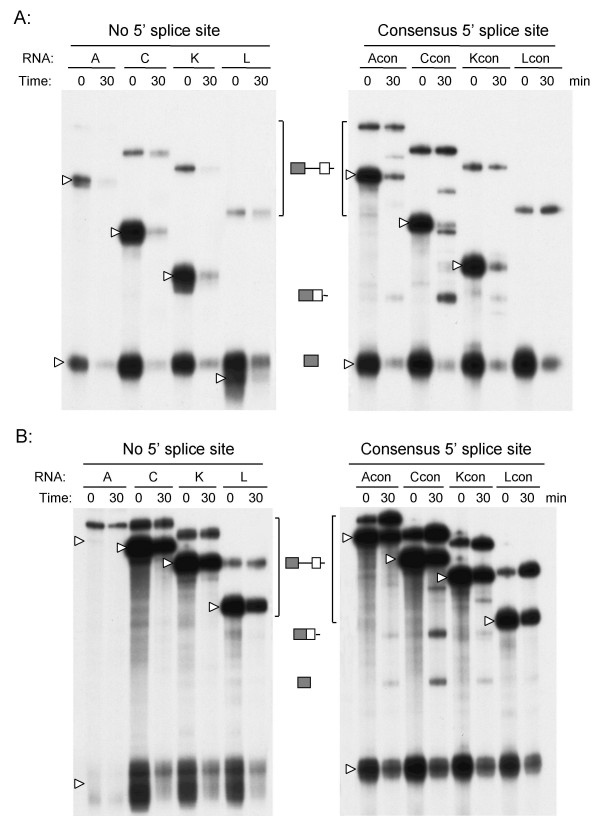

Splicing complexes are observed on all templates in-vitro irrespective of splicing

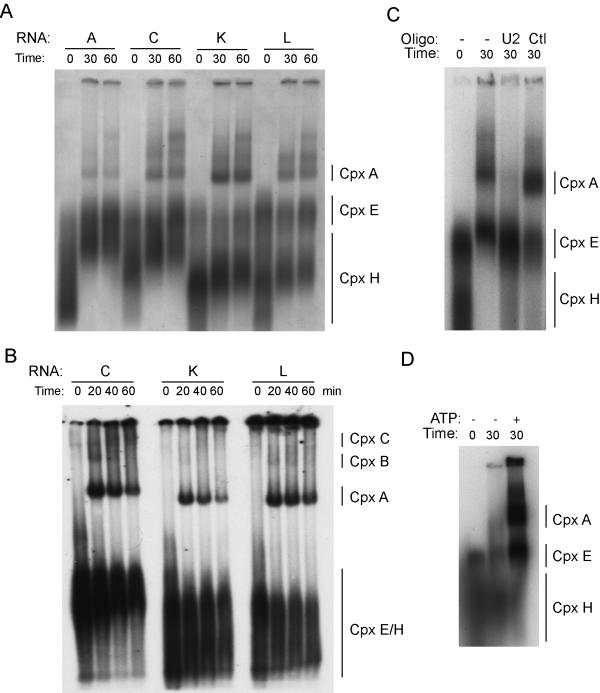

Although we had evidence for occupancy of the 5' splice site by U1 snRNP, it was possible that the observed RNase H protection was not related to the formation of splicing complexes. Consequently, complex assembly gels were run to verify that splicing complexes were indeed assembled on the templates. The four templates lacking the terminal 5' splice site were used. Only template C containing the purine-rich enhancer was spliced efficiently under these circumstances (Fig. 2). These templates were incubated with HeLa nuclear extract under splicing conditions for increasing times, then loaded directly onto agarose gels (Fig. 7A). Spliceosomal E complexes and A complexes were observed on all templates, but identification of higher complexes was not possible due to smearing on the agarose gel. To achieve better resolution of the complexes, splicing complex assembly assays were also run on native polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 7B). A strong A complex was observed on all templates, with much weaker B and C complexes only visible on template C that is actively spliced. We verified that the A complexes were bona-fide splicing complexes by demonstrating that the complexes were dependent on ATP and contained the U2 snRNP. Prior treatment of the nuclear extract with an oligonucleotide directed against the U2 snRNA and RNaseH to eliminate the U2 snRNP, prevented the formation of the complex indicating that it contained U2 snRNP and thus corresponds to the splicing A complex (Fig. 7C). Treatment with a control oligonucleotide was without effect. Omission of ATP from the splicing buffer prevented the formation of the retarded A complex but did not alter E complex formation (Fig. 7D). These findings confirm the conclusion from the RNaseH protection experiments that both the 5' and 3' splice sites are occupied on all templates in a pre-spliceosomal complex irrespective of splicing.

Figure 7.

Splicing complexes are assembled on all templates. RNA templates were derived from minigenes A, C, K, and L and lacked the terminal 5' spice site of exon 11. The RNAs were incubated in 40 % HeLa nuclear extract on ice or for increasing times at 30°C to allow the formation of splicing complexes. Reactions were loaded directly onto 2% low-melting agarose gels (Panel A) or 4% native polyacrylamide gels (Panel B) and complexes separated by electrophoresis. Gels were dried under vacuum and exposed to film. The non-specific hnRNP complex H is indicated as well as the pre-spliceosomal complexes E and A. In Panel B, the higher order complexes B and C are indicated. In Panel C, the nuclear extract was pretreated with RNase H and an oligonucleotide complementary to the first 14 nucleotides of the U2 snRNA or a control oligonucleotide before complex assembly. In Panel D, the assembly reactions were performed in the absence or presence of ATP.

Discussion

In this paper, we investigated how the small, 36-nucleotide, exon 11 of the insulin receptor gene is skipped to generate a mature insulin receptor A isoform. We demonstrated that skipping of exon 11 in-vivo requires sub-optimal splice sites, as increasing the strength of either the 5' or 3' splice site of exon 11 leads to constitutive incorporation of the exon. In contrast, we found that strengthening of the upstream and downstream splice donor and acceptor sites on the neighboring exons leads to decreased exon incorporation in-vivo. These results are consistent with the exon-definition model proposed by Berget, in which exons are defined in the context of genomic sequence by both flanking splice sites [35]. Binding of the U1 snRNP to the 5' splice site of the exon facilitates recruitment of factors, such as SF1 and U2AF65/35 that recognize the upstream 3' splice site [36]. Stabilization of the protein complex on the 3' splice site by these bridging interactions across the exon then facilitates interaction with the U1 snRNP bound to the 5' splice site of the previous exon allowing the intron to be defined [37,38]. This method of exon definition may have evolved to minimize the recognition of cryptic 3' splice sites that are not associated with exons, as 3' splice site sequences are not strictly defined and occur with high frequency throughout the genome.

Small or microexons such as IR exon 11 impose a further constraint on exon definition. Although the U1 snRNP may recognize the 5' splice site on such a small exon, it may not be able to interact productively with the 3' splice site factors due to steric constraints over the small distance. Usually in these cases, increasing the length of the exon overcomes this constraint [39]. Exonic splicing enhancers are occasionally found in such small exons, and may compensate for the steric hindrance to exon definition [40]. Consistent with this, we have previously defined both positive and negative regulatory sequences in exon 11 in the IR gene. The exon-definition model may also explain the decrease in exon 11 recognition when splice sites on the flanking exons are strengthened. Splicing of RNA is co-transcriptional and generally proceeds in a linear manner along the RNA. Each exon may itself be defined on the nascent transcript by the RNA polymerase complex. If assembly of the U1/U2 snRNPs and/or other splicing factors that define a particular exon is slow, whether due to steric constraints or weak splice sites, the next downstream exon may be defined preferentially. This kinetic competition could lead to skipping of the exon.

We obtained similar results when splicing of exon 11 was studied in-vitro. Efficient splicing was only seen if a terminal 5' splice site was included in the RNA. In the absence of this terminal splice site, only a template that contained a purine-rich intronic enhancer was spliced efficiently. In the presence of the natural 5' splice site, all templates were spliced but to different extents. Again, the most efficiently spliced template contained the intronic enhancer, a template containing an inhibitory element was spliced less efficiently, and a template containing both was intermediate. Addition of a consensus splice site to the templates further increases the efficiency of splicing but the effect of the intronic inhibitor is lost, as is seen in-vivo. Thus, the in-vitro splicing results are also consistent with the exon-definition model.

Although we do not know how the intronic enhancer promotes splicing in the absence of the terminal splice site, two scenarios can be envisioned. The fact that this enhancer is very GA rich might indicate that SR proteins functionally replace the terminal 5' splice site and stabilize binding of U2AF to the 3' splice site. Exonic binding sites for the SR proteins SF2/ASF and SC35 have been shown to stabilize binding of U2AF to 3' splice sites [24,26,27,30]. One argument against this model is that co-transfection of expression vectors for SRp20, SC35, SRp40, SRp55, or SRp75 did not alter exon incorporation in-vivo (data not shown). Unfortunately, this experiment is of limited value as most SR proteins are in excess, so further overexpression might not show a phenotype. Depletion of individual or groups of SR proteins would be more convincing but is harder to achieve. Alternatively, the enhancer may recruit the U1 snRNP directly, independently of the terminal 5' splice site. McCullough and Berget have shown that the U1 snRNP helps to define small exons by base-pairing with intronic GGG triplets [41]. The purine-rich intronic enhancer in the IR gene contains nine GGG triplets, so targeting the U1 snRNP to the enhancer may stabilize the binding of U2AF to the 3' splice site in the same manner as when the U1 snRNP is bound to the 5' splice site of the exon. This enhancement may be position dependent, however, as insertion of random genomic sequences containing GGG sequences into exons has been shown to inhibit splicing [42].

Noticeably different results were obtained, however, when we examined splice site occupancy and splicing complex assembly. Using RNaseH to probe occupancy of the 5' and 3' splice sites, we observed that these sites were occupied on all of the splicing templates irrespective of how the templates splice in-vitro. This finding was confirmed by complex assembly assays. The spliceosomal A complex was observed on all templates, even those that did not splice efficiently. We verified that these corresponded to bona-fide pre-spliceosomal complexes by demonstrating that they were ATP-dependent and contained the U2 snRNP. This implies that the regulation of splicing on this template must occur after the initial recognition of the splice sites but before the first catalytic step, as there was good concordance between splicing intermediates and products for all templates. These findings are not consistent with the exon-definition model. However, a number of studies have questioned this model. Recognition of 5' splice sites by the U1 snRNP does not always correlate with splicing efficiency, especially for substrates that contain alternative 5' splice sites. Nasim et al. demonstrated that repression of proximal 5' splice site use by hnRNP A1 was related to RNA looping and not U1 snRNP binding [43]. This may be a special case as the looping was mediated by duplicate high affinity hnRNP A1 binding sites flanking the alternative exon and could be mimicked by inverted repeat sequences. Eperon et al. showed that the SF2/ASF-mediated enhancement of proximal 5' splice site use was accompanied by enhanced binding of U1 snRNP to both 5' splice sites, but the hnRNP A1-mediated repression of proximal 5' splice site use was related to reduced U1 snRNP binding to both sites [44]. They concluded that shift from the use of the distal 5' splice site by the addition of hnRNP A1 resulted not from a reduction in U1 snRNP binding, but by sequestration of the site.

At the 3' end of the intron, recent publications have also questioned the U2AF-recruitment hypothesis. Blencowe and co-workers found that the splicing accessory factor U2AF-65 bound to a double-sex (dsx)pre-mRNA irrespective of splicing [36]. This mRNA, which lacked the exonic splicing enhancer, was not spliced in-vitro, but U2AF-65 was still bound to the 3' splice site. The binding of U2AF-65 required the presence of the U1 snRNP on the 5' splice site but did not require SR proteins. It's possible that another protein such as the BBP/SF1 was mediating the interaction between the 5' and 3' splice sites in the absence of SR proteins. The recruitment of SR proteins and splicing of the RNA was still dependent on the enhancer, however, suggesting a role for SR proteins other than to recruit U2AF-65. The authors suggested that this function may be to recruit the splicing co-activator SRm160/300 that is required for the formation of a functional spliceosome.

The recruitment model of exon-definition is attractive as it makes little teleological sense to assemble splicing complexes on non-functional splice sites. However, spliceosomal assembly on a number of decoy sites has been shown. Cote et al. showed that non-productive splicing complexes containing the U2 snRNP are formed between the 5' splice site of exon 9 and a pseudo 3' splice site sequence in the downstream intronic inhibitory element in the caspase 2 pre-mRNA [45]. Similar dead-end complexes are formed on the immunoglobulin M2 exonic silencer [46]. Sun et al. have investigated the splicing of pseudoexons that are present through out the genome [47]. These pseudoexons have good matches to consensus splice site sequences but are not used. They showed that both the 5' splice site and the polypyrimidine tract are defective and identified an upstream inhibitory element. The mechanism for inhibition is not known but the authors suggest that it might involve binding of U2 snRNP in a dead-end complex. A potential pseudo 3' splice site also exists in intron 10 of the IR gene (U16GACAG). While we have no evidence for assembly on this site, it is worth noting that internal deletions of intron 10, which show enhanced exon incorporation in-vivo, lack this pseudo splice site.

Our findings raise a number of questions. Firstly, why are some pre-spliceosomal complexes non-functional on selected IR templates? One possible explanation is that splicing of exon11 in-vitro is regulated either at the level of recruitment of the U4/5/6 tri-snRNP or the subsequent rearrangements to form the active splicing complex, as has been proposed for dsx splicing. In this model, factors binding to the intronic regulatory sequences could stabilize the U1 snRNP interaction at the 5' splice site and prevent the stable accommodation of the tri-snRNP complex. This is supported by a recent study defining 5' splice sites by functional selection. Lund and Kjems highlighted an inherent discontinuity between stable complex A formation and progression to complex B and active splicing [48]. In their experiments, extended complementarity between the 5' splice site and the U1 snRNA promoted complex A formation but inhibited subsequent splicing. Truncation of the U1 snRNA allowed a rapid transition from complex A to complex B and restored splicing. The authors concluded that stable U1 snRNA binding is advantageous for assembly of commitment complexes, but inhibitory for the entry of the U4/5/6 tri-snRNP due to delayed release of the U1 snRNP.

Our minigene transfection studies are consistent with the exon-definition model, but the in-vitro studies suggest that regulation may not be explained by the simple recruitment model. How can we reconcile the in-vivo and in-vitro results? The finding that the splice sites are occupied in-vitro does not necessarily imply the sites are occupied in-vivo. It may be that competitive splice site recognition is the dominant regulatory mechanism, but the slower kinetics of splicing in-vitro allows assembly of splicing complexes on weak splice sites that would otherwise be ignored. Alternatively, the deleted intron used for in-vitro splicing studies may have caused a shift from exon definition to intron definition. Spliceosomal complexes could have assembled due to interactions across introns, which would not occur in-vivo where the introns are 2.3 kB and 9 Kb. These complexes may be functionally distinct from complexes assembled across exons.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that alternative splicing of exon 11 of the IR gene in-vivo involves sub-optimal splice sites consistent with the exon-definition model. However, we observed occupancy of the 5' splice site by U1 snRNP, and the formation of non-functional spliceosomal A complexes, containing U2-snRNP, on exon 11 RNA templates in-vitro. This observation suggests that the regulation of splicing of this exon in-vitro is not explained by the simple recruitment model. Further studies to analyze splice site recognition and spliceosomal complex assembly in-vivo will be required to resolve these questions.

Methods

Reagents

Cell culture media and antibiotics were from Gibco (Grand Island, NY), reverse transcriptase (SuperScript II), Lipofectamine Plus and oligo-dT were purchased from Life Technologies (Rockville, MD) and fetal calf serum from Omega Scientific (Tarzana, CA). Nuclear extracts were purchased from Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corporation (Westbury, NY). RNase H was from USB Corporation (Cleveland, OH). RNA cap analog was purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverley, MA). Nucleotides were purchased from Amersham/Pharmacia (Piscataway, NJ), T7 RNA Polymerase was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). The QuickChange mutagenesis kit and CalPhos Maximizer transfection kit were from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). All plasmids were constructed using standard techniques. Point mutations were introduced into minigenes using the QuickChange mutagenesis kit and verified by dideoxysequencing. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MI) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Cell culture and transfections

HepG2 and HeLa cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment. HepG2 and HeLa cells were cultured in MEM-Earle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and gentamycin sulfate antibiotic. Cells were plated in 6-well dishes for transfection. Hela cells were transfected using the calcium phosphate method. HepG2 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine Plus following the manufacturers protocol. Splice site strength was calculated using Shapiro and Senapathy Splice Score http://home.snafu.de/probins/Splice/splice.html.

RT-PCR analysis

RNA was extracted from transfected cells using RNAzolB (TelTest, TX) following manufacturers directions and precipitated twice. To avoid interference from partially spliced intermediates, RNA was purified by mRNA Capture (Roche Biosciences, IN) before reverse transcription using SuperScript II and oligo-dT as primer. PCR amplification of IR splice products derived from the minigenes was performed as published previously. Splice products were resolved on 4% agarose gels (Latitude HT, BioWhittaker Molecular Applications, Rockland, ME) and quantified using a Kodak EDAS290 imaging system.

In-vitro splicing

Templates for in-vitro transcription were generated by PCR from minigenes A, C, K, and L [11]. The 5' PCR primer contained a T7 promoter to allow in-vitro transcription. Three different 3' PCR primers were used to generate templates either lacking the 5' splice site on exon 11, or containing the 7 nucleotide natural splice site (GUAUGAC), or a 7 nucleotide consensus splice site (GUAAGUA). Templates were gel purified before use.

Capped and labeled pre-mRNA templates were transcribed using T7 RNA polymerase and 32P-GTP as published previously [49]. RNAs were gel-purified before use. Splicing reactions were performed by incubating 20 fmol of pre-mRNA at 30°C in the presence of 0.5 mM ATP, 8 mM MgCl2, 2.6% polyvinylalcohol, 60 mM KCl and 40% HeLa nuclear extract. Reaction products were extracted with phenol and precipitated in ethanol before electrophoresis on 5% sequencing gels. Gels were exposed to film at -70°C for different times. Quantification of splicing efficiency was performed by densitometric scanning of autoradiographs (Agfa Arcus II scanner and Kodak 1D software, Ver. 3.5) from multiple exposures of the gels. First step splicing efficiency was defined as the sum of free 5' exon plus spliced mRNA versus the total of free 5' exon, spliced mRNA and unspliced RNA template. Second step efficiency was defined as the spliced mRNA versus the total of free 5' exon, spliced mRNA plus unspliced RNA. All bands intensities were adjusted for the number of G residues.

RNase H protection assay

Duplicate splicing reactions were set up as above. One reaction was kept on ice while the other was incubated at 30°C for 30 min to allow the formation of splicing complexes. Oligonucleotides were added to a final concentration of 10 μM, then 2 U RNase H was added and the reaction incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Reaction products were extracted and analyzed by gel electrophoresis as before. The following oligonucleotides were used: 5' splice site, GTCCTGACCTGG; branch point sequence, CCTTTGAGGACAG; 3' splice site, CTGTGGAAACAAAAC; exon 10 control, GTGGGGACGAAA. The percentage of uncleaved RNA was determined by densitometric scanning of autoradiographs for both cleavage products and the remaining uncleaved RNA. Relative protection was calculated as the ratio of the percentage of uncleaved RNA in reactions incubated at 30°C versus the percentage of uncleaved RNA in reactions kept at 0°C. In some experiments, the U1 snRNP was depleted by treating the nuclear extract for 20 min at 30°C with 2 U RNase H and 10 μM of an oligonucleotide complementary to nucleotides 1–14 of the U1 snRNA (TGCCAGGTAAGTAT).

Spliceosomal complex assembly assay

Splicing reactions were performed as above in 40% HeLa nuclear extract. At the appropriate times, heparin was added to 5 μg/μl and the reaction analyzed on 5% non-denaturing, non-reducing acrylamide gels or 2% low-melting agarose gels. Acrylamide gels were run for 16 h at 4 W at room temperature, agarose gels were run for 3.5 h at 70 V at 4°C. Gels were fixed and dried under vacuum then exposed to film. In some experiments, the U2 snRNP was depleted by treating the nuclear extract for 20 min at 30°C with 2 U RNase H and 10 μM of an oligonucleotide complementary to nucleotides 1–15 of the U2 snRNA (GGCCGAGAAGCGAT) or a control oligonucleotide (GGGGTGAATTCTTTGCCA). In experiments in the absence of ATP, the nuclear extract was incubated at 30°C for 20 min before the addition of RNA to deplete residual ATP in the nuclear extract.

Abbreviations

IR, insulin receptor; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; snRNA, small nuclear RNA; snRNP, small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle; SR protein, serine-arginine rich splicing factor

Authors' contributions

NJGW performed the in-vitro splicing reactions and complex assembly experiments. LGE performed the transfections and RT-PCR assays. MC and LR constructed mutations. SLC supervised the in-vitro splicing, RNaseH protection and complex assembly experiments and provided essential reagents and advice.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Merit Review Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs (to N.J.G.W.) and by the Joint Research Board of St. Bartholomew's Hospital (to S.L.C.). N.J.G.W. is a faculty member of the UCSD Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program.

Contributor Information

Nicholas JG Webster, Email: nwebster@ucsd.edu.

Lui-Guojing Evans, Email: guojing@hotmail.com.

Matt Caples, Email: mattcaples@hotmail.com.

Laura Erker, Email: lauraerker@yahoo.com.

Shern L Chew, Email: s.l.chew@mds.qmw.ac.uk.

References

- Moller DE, Yokota A, Caro JF, Flier JS. Tissue-specific expression of two alternatively spliced insulin receptor mRNAs in man. MolEndocrinol. 1989;3:1263–1269. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-8-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren S, Arner P, Luthman H. Insulin receptor ribonucleic acid levels and alternative splicing in human liver, muscle, and adipose tissue: tissue specificity and relation to insulin action. JClinEndocrinolMetab. 1994;78:757–762. doi: 10.1210/jc.78.3.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca F, Pandini G, Scalia P, Sciacca L, Mineo R, Costantino A, Goldfine ID, Belfiore A, Vigneri R. Insulin receptor isoform A, a newly recognized, high-affinity insulin-like growth factor II receptor in fetal and cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3278–3288. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerer M, Sesti G, Seffer E, Obermaier-Kusser B, Pongratz DE, Mosthaf L, Haring HU. Altered pattern of insulin receptor isotypes in skeletal muscle membranes of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic subjects. Diabetologia. 1993;36:628–632. doi: 10.1007/BF00404072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaki A, Webster NJ. Effect of dexamethasone on the alternative splicing of the insulin receptor mRNA and insulin action in HepG2 hepatoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21990–21996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosthaf L, Vogt B, Haring HU, Ullrich A. Altered expression of insulin receptor types A and B in the skeletal muscle of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4728–4730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren S, Zierath J, Galuska D, Wallberg-Henriksson H, Luthman H. Differences in the ratio of RNA encoding two isoforms of the insulin receptor between control and NIDDM patients. The RNA variant without Exon 11 predominates in both groups. Diabetes. 1993;42:675–681. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren S, Li LS, Luthman H. Regulation of human insulin receptor RNA splicing in HepG2 cells: effects of glucocorticoid and low glucose concentration. BiochemBiophysResCommun. 1994;199:277–284. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips AV, Timchenko LT, Cooper TA. Disruption of splicing regulated by a CUG-binding protein in myotonic dystrophy. Science. 1998;280:737–741. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savkur RS, Philips AV, Cooper TA. Aberrant regulation of insulin receptor alternative splicing is associated with insulin resistance in myotonic dystrophy. Nat Genet. 2001;29:40–47. doi: 10.1038/ng704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaki A, Nelson J, Webster NJ. Identification of intron and exon sequences involved in alternative splicing of insulin receptor pre-mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10331–10337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PA. Split genes and RNA splicing. Cell. 1994;77:805–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MJ. Intron recognition comes of AGe. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:14–16. doi: 10.1038/71207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcarcel J, Gaur RK, Singh R, Green MR. Interaction of U2AF65 RS region with pre-mRNA branch point and promotion of base pairing with U2 snRNA. Science. 1996;273:1706–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamore PD, Patton JG, Green MR. Cloning and domain structure of the mammalian splicing factor U2AF. Nature. 1992;355:609–614. doi: 10.1038/355609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merendino L, Guth S, Bilbao D, Martinez C, Valcarcel J. Inhibition of msl-2 splicing by Sex-lethal reveals interaction between U2AF35 and the 3' splice site AG. Nature. 1999;402:838–841. doi: 10.1038/45602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Romfo CM, Nilsen TW, Green MR. Functional recognition of the 3' splice site AG by the splicing factor U2AF35. Nature. 1999;402:832–835. doi: 10.1038/45996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorio DA, Blumenthal T. Both subunits of U2AF recognize the 3' splice site in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1999;402:835–838. doi: 10.1038/45597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abovich N, Rosbash M. Cross-intron bridging interactions in the yeast commitment complex are conserved in mammals. Cell. 1997;89:403–412. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund JA, Chua K, Abovich N, Reed R, Rosbash M. The splicing factor BBP interacts specifically with the pre-mRNA branchpoint sequence UACUAAC. Cell. 1997;89:781–787. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rain JC, Rafi Z, Rhani Z, Legrain P, Kramer A. Conservation of functional domains involved in RNA binding and protein-protein interactions in human and Saccharomyces cerevisiae pre-mRNA splicing factor SF1. RNA. 1998;4:551–565. doi: 10.1017/S1355838298980335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer A. The structure and function of proteins involved in mammalian pre-mRNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:367–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AJ. Alternative splicing of pre-mRNA: developmental consequences and mechanisms of regulation. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:279–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo P, Maniatis T. The splicing factor U2AF35 mediates critical protein-protein interactions in constitutive and enhancer-dependent splicing. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1356–1368. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohtz JD, Jamison SF, Will CL, Zuo P, Luhrmann R, Garcia-Blanco MA, Manley JL. Protein-protein interactions and 5'-splice-site recognition in mammalian mRNA precursors. Nature. 1994;368:119–124. doi: 10.1038/368119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Maniatis T. Specific interactions between proteins implicated in splice site selection and regulated alternative splicing. Cell. 1993;75:1061–1070. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90316-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigueur A, La Branche H, Kornblihtt AR, Chabot B. A splicing enhancer in the human fibronectin alternate ED1 exon interacts with SR proteins and stimulates U2 snRNP binding. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2405–2417. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley JL, Tacke R. SR proteins and splicing control. GenesDev. 1996;10:1569–1579. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staknis D, Reed R. SR proteins promote the first specific recognition of Pre-mRNA and are present together with the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle in a general splicing enhancer complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7670–7682. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Hoffmann HM, Grabowski PJ. Intrinsic U2AF binding is modulated by exon enhancer signals in parallel with changes in splicing activity. RNA. 1995;1:21–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RC, Black DL. The polypyrimidine tract binding protein binds upstream of neural cell-specific c-src exon N1 to repress the splicing of the intron downstream. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4667–4676. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcarcel J, Singh R, Zamore PD, Green MR. The protein Sex-lethal antagonizes the splicing factor U2AF to regulate alternative splicing of transformer pre-mRNA. Nature. 1993;362:171–175. doi: 10.1038/362171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talerico M, Berget SM. Effect of 5' splice site mutations on splicing of the preceding intron. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6299–6305. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eperon IC, Ireland DC, Smith RA, Mayeda A, Krainer AR. Pathways for selection of 5' splice sites by U1 snRNPs and SF2/ASF. EMBO J. 1993;12:3607–3617. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berget SM. Exon recognition in vertebrate splicing. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2411–2414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Blencowe BJ. Distinct factor requirements for exonic splicing enhancer function and binding of U2AF to the polypyrimidine tract. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35074–35079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achsel T, Shimura Y. Factors involved in the activation of pre-mRNA splicing from downstream splicing enhancers. JBiochem(Tokyo) 1996;120:53–60. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabot B. Directing alternative splicing: cast and scenarios. Trends Genet. 1996;12:472–478. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DL. Does steric interference between splice sites block the splicing of a short c-src neuron-specific exon in non-neuronal cells? Genes Dev. 1991;5:389–402. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo T, Sterner DA, Berget SM. An intron splicing enhancer containing a G-rich repeat facilitates inclusion of a vertebrate micro-exon. RNA. 1996;2:342–353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough AJ, Berget SM. An intronic splicing enhancer binds U1 snRNPs to enhance splicing and select 5' splice sites. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9225–9235. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.24.9225-9235.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother WG, Chasin LA. Human genomic sequences that inhibit splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6816–6825. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.18.6816-6825.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasim FU, Hutchison S, Cordeau M, Chabot B. High-affinity hnRNP A1 binding sites and duplex-forming inverted repeats have similar effects on 5' splice site selection in support of a common looping out and repression mechanism. RNA. 2002;8:1078–1089. doi: 10.1017/S1355838202024056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eperon IC, Makarova OV, Mayeda A, Munroe SH, Caceres JF, Hayward DG, Krainer AR. Selection of alternative 5' splice sites: role of U1 snRNP and models for the antagonistic effects of SF2/ASF and hnRNP A1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8303–8318. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.22.8303-8318.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote J, Dupuis S, Jiang Z, Wu JY. Caspase-2 pre-mRNA alternative splicing: Identification of an intronic element containing a decoy 3' acceptor site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:938–943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031564098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan JL, Green MR. Pre-mRNA splicing of IgM exons M1 and M2 is directed by a juxtaposed splicing enhancer and inhibitor. Genes Dev. 1999;13:462–471. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Chasin LA. Multiple splicing defects in an intronic false exon. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6414–6425. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.17.6414-6425.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund M, Kjems J. Defining a 5' splice site by functional selection in the presence and absence of U1 snRNA 5' end. RNA. 2002;8:166–179. doi: 10.1017/S1355838202010786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda A, Krainer AR. Mammalian in vitro splicing assays. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;118:315–321. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-676-2:315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]