ABSTRACT

We identified three nonpeptidic HIV-1 protease inhibitors (PIs), GRL-015, -085, and -097, containing tetrahydropyrano-tetrahydrofuran (Tp-THF) with a C-5 hydroxyl. The three compounds were potent against a wild-type laboratory HIV-1 strain (HIV-1WT), with 50% effective concentrations (EC50s) of 3.0 to 49 nM, and exhibited minimal cytotoxicity, with 50% cytotoxic concentrations (CC50) for GRL-015, -085, and -097 of 80, >100, and >100 μM, respectively. All the three compounds potently inhibited the replication of highly PI-resistant HIV-1 variants selected with each of the currently available PIs and recombinant clinical HIV-1 isolates obtained from patients harboring multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants (HIVMDR). Importantly, darunavir (DRV) was >1,000 times less active against a highly DRV-resistant HIV-1 variant (HIV-1DRVRP51); the three compounds remained active against HIV-1DRVRP51 with only a 6.8- to 68-fold reduction. Moreover, the emergence of HIV-1 variants resistant to the three compounds was considerably delayed compared to the case of DRV. In particular, HIV-1 variants resistant to GRL-085 and -097 did not emerge even when two different highly DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants were used as a starting population. In the structural analyses, Tp-THF of GRL-015, -085, and -097 showed strong hydrogen bond interactions with the backbone atoms of active-site amino acid residues (Asp29 and Asp30) of HIV-1 protease. A strong hydrogen bonding formation between the hydroxyl moiety of Tp-THF and a carbonyl oxygen atom of Gly48 was newly identified. The present findings indicate that the three compounds warrant further study as possible therapeutic agents for treating individuals harboring wild-type HIV and/or HIVMDR.

IMPORTANCE Darunavir (DRV) inhibits the replication of most existing multidrug-resistant HIV-1 strains and has a high genetic barrier. However, the emergence of highly DRV-resistant HIV-1 strains (HIVDRVR) has recently been observed in vivo and in vitro. Here, we identified three novel HIV-1 protease inhibitors (PIs) containing a tetrahydropyrano-tetrahydrofuran (Tp-THF) moiety with a C-5 hydroxyl (GRL-015, -085, and -097) which potently suppress the replication of HIVDRVR. Moreover, the emergence of HIV-1 strains resistant to the three compounds was considerably delayed compared to the case of DRV. The C-5 hydroxyl formed a strong hydrogen bonding interaction with the carbonyl oxygen atom of Gly48 of protease as examined in the structural analyses. Interestingly, a compound with Tp-THF lacking the hydroxyl moiety substantially decreased activity against HIVDRVR. The three novel compounds should be further developed as potential drugs for treating individuals harboring wild-type and multi-PI-resistant HIV variants as well as HIVDRVR.

INTRODUCTION

Currently available combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection and AIDS potently suppresses the replication of HIV-1 and significantly extends the life expectancy of HIV-1-infected individuals (1–4). Recent analyses have revealed that mortality rates for HIV-1-infected persons have become close to that of general population and that the recent first-line cART with integrase inhibitors or boosted protease inhibitor (PI)-based regimens has made the development of HIV-1 resistance significantly less likely over an extended period of time (5, 6). A recent study reported that 20-year-old HIV-1-infected individuals who started cART between 2003 and 2005 are expected to live an additional 49 years, to the age of 69 (7, 8). Notably, cART has been shown to definitively reduce sexual transmission of HIV-1 in the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 052 study, where a 96% reduction in the rate of sexual transmission has been seen with cART (9).

However, even the currently most frequently used antiretroviral therapeutics, such as tenofovir, reportedly increase the risks of chronic renal diseases and bone density loss (10, 11). Moreover, our ability to provide effective long-term cART for HIV-1 infection remains a complex issue, since many of those who initially achieve favorable viral suppression to undetectable levels eventually suffer treatment failure (12).

Darunavir (DRV), the latest protease inhibitor approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), contains a unique substrate sequence position 2 (P2) functional group in its structure, bis-tetrahydrofuranylurethane (bis-THF), and potently inhibits the replication of not only wild-type HIV-1 (HIV-1 strains not carrying known major amino acid substitutions) but also multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants (13–15). It is also known that DRV has a high genetic barrier against HIV-1 development of resistance (referred to here as a genetic barrier) apparently because of its dual antiviral activity, enzymatic inhibition activity, and dimerization inhibition activity of HIV-1 protease (16–20). However, the emergence of DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants has been reported both in vitro and in vivo, and patients with such DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants have experienced treatment failure (21–26). Hence, continuous efforts to develop more potent drugs with higher genetic barriers are required to combat such DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants.

In the present work, we evaluated three newly synthesized nonpeptidic HIV-1 protease inhibitors, GRL-015, -085, and -097, which contain a bicyclic P2 functional group, tetrahydropyrano-tetrahydrofuran (Tp-THF) carrying a hydroxyl moiety at its C-5 position and show highly potent antiviral activity against not only wild-type HIV-1 but also a variety of multi-PI-resistant HIV-1 variants, including highly DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants. Interestingly, it was found in this study that the removal of the hydroxyl moiety significantly reduces the antiviral activity against drug-resistant variants. In in vitro selection, GRL-015, -085, and -097 all demonstrated high genetic barriers against resistance development when four different HIV-1 populations were used as starting populations. The X-ray crystal structural analyses revealed that the Tp-THF moiety of the three protease inhibitors forms effective hydrogen bond interactions with the main-chain atoms of the protease active site amino acids, Asp29 and Asp30, as does the bis-THF moiety of DRV (15). Moreover, the C-5 hydroxyl moiety had a strong hydrogen bond with the backbone of Gly48 of the protease. The bindings with protease likely play key roles in their highly potent activity against both wild-type and drug-resistant HIV-1 strains and their substantially high genetic barrier.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

MT-2 and MT-4 cells were grown in RPMI 1640-based culture medium, while COS7 cells were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium. These media were supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; PAA Laboratories GmbH, Linz, Austria) plus 50 U of penicillin and 50 μg of kanamycin per ml. For the drug susceptibility assay and selection experiments, eleven HIV-1 clinical strains (HIV-1A, HIV-1B, HIV-1C, HIV-1G, HIV-1TM, HIV-1MM, HIV-1JSL, HIV-1SS, HIV-1ES, HIV-1EV, and HIV-113–52), which were originally isolated from patients with AIDS who were enrolled in an open-labeled clinical study of amprenavir (APV) and abacavir (ABC) at the Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, were randomly chosen from the enrollees, who had failed APV-plus-ABC therapy (27, 28) or a phase I/II study of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (29). Such patients had failed existing anti-HIV-1 regimens after receiving 7 to 11 anti-HIV-1 drugs over the previous 24 to 83 months in late 1990s. The clinical strains used in the present study contained 8 to 16 amino acid substitutions in the protease-encoding region (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), which have reportedly been associated with HIV-1 resistance to various PIs and have been genotypically and phenotypically characterized as multiprotease inhibitor (multi-PI)-resistant HIV-1 (30). Seven recombinant clinical HIV-1 isolates (rCLHIV-1F16, rCLHIV-1F39, rCLHIV-1V42, rCLHIV-1V44, rCLHIV-1T45, rCLHIV-1T48, and rCLHIV-1F71) were kindly provided by Robert Shafer of Stanford University and were produced using recombinant HIVNL4-3-based infectious molecular clones generated by ligating patient-derived amplicons encompassing approximately 200 nucleotides of Gag (beginning at the unique ApaI restriction site), the entire protease, and the first 72 nucleotides of reverse transcriptase using the expression vector pNLPFB (a generous gift from Tomozumi Imamichi of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases). The recombinant clinical HIV-1 isolates were chosen from 32 isolates that had been obtained from multi-PI-treated patients whose protease genotype contained prototypical patterns of PI resistance. The median duration of continuous PI treatment was 7.5 years (range, 6 to 10 years). The median number of PIs such patients received was 5 (range, 4 to 8 [excluding the use of ritonavir for pharmacokinetic boosting]).

Antiviral agents.

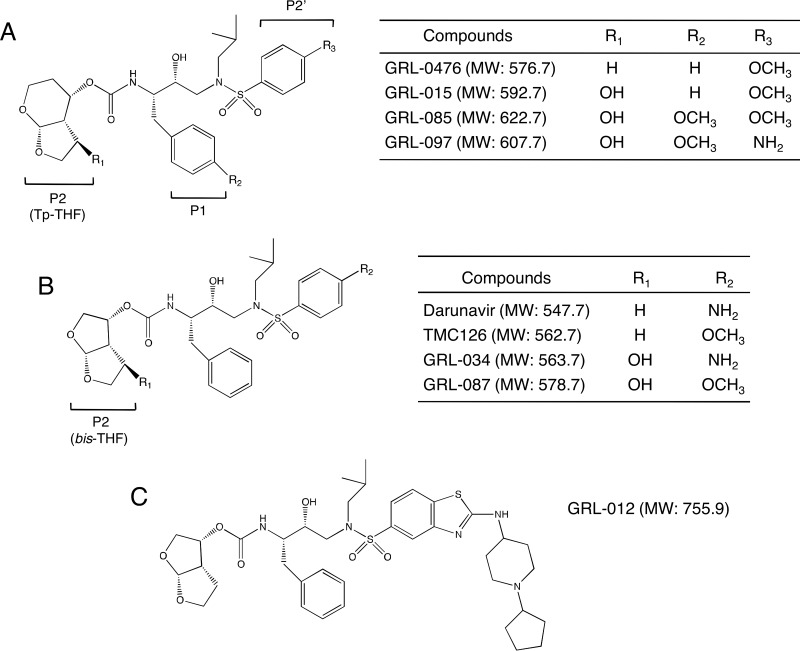

The nonpeptidic PIs GRL-015, -085, and -097 (Fig. 1) (molecular weights of 592.7, 622.7, and 606.7, respectively), which contain tetrahydropyrano-tetrahydrofuran (Tp-THF) with a hydroxyl moiety at the C-5 position, were synthesized. The method of synthesis of GRL-015, -085, and -097 will be published elsewhere by A. K. Ghosh et al. The structure of GRL-012 synthesized in this study is the same as that of TMC-310911 (31). DRV was synthesized as described previously (32). Saquinavir (SQV) was kindly provided by Roche Products Ltd. (Welwyn Garden City, United Kingdom) and Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, IL), respectively. Amprenavir (APV) was a kind gift from GlaxoSmithKline (Research Triangle Park, NC). Lopinavir (LPV) were kindly provided by Japan Energy Inc., Tokyo, Japan. Atazanavir (ATV) was a kind gift from Bristol Myers Squibb (New York, NY). Tipranavir (TPV) was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, National Institutes of Health. Azidothymidine (AZT) and dolutegravir (DTG) were purchased from US Biological (Swampscott, MA). Lamivudine (3TC) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) was purchased from BioVision (Milpitas, CA).

FIG 1.

Structures of GRL-015, -085, and -097. The structures of compounds used in this study, containing Tp-THF (A) or bis-THF (B) at the P2 site, are shown. The structure of GRL-012 (C) is also shown.

Drug susceptibility assay.

The susceptibility of HIV-1LAI to various drugs was determined as previously described (28), with minor modifications. Briefly, MT-2 cells (2 × 104/ml) were exposed to 100 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50s) of HIV-1LAI or HIV-2ROD in the presence or absence of various concentrations of drugs in 96-well microtiter culture plates, followed by incubation at 37°C for 7 days. After 100 μl of the culture medium was removed from each well, 3-(4,5-dimetylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution (10 μl; 7.5 mg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline) was added to each well, followed by incubation at 37°C for 3 h. After incubation to dissolve the formazan crystals, 100 μl of acidified isopropanol containing 4% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 was added to each well, and the optical density was measured by using a kinetic microplate reader (VMax; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). All assays were performed in duplicate. To determine the drug susceptibility of infectious molecular HIV-1 clones (including HIV-1NL4-3) and each PI-selected HIV-1 variant, MT-4 cells were used as target cells. MT-4 cells (105/ml) were exposed to 50 TCID50s of infectious molecular HIV-1 clones and PI-selected HIV-1 variants in the presence or absence of various concentrations of drugs and were incubated at 37°C. On day 7 of culture, the supernatant was harvested and the amount of p24 Gag protein was determined by using a fully automated chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay system (Lumipulse F; Fujirebio Inc., Tokyo, Japan) (30). The drug concentrations that suppressed the production of p24 Gag protein by 50% (50% effective concentration [EC50]) were determined by comparison with the level of p24 production in drug-free control cell cultures. All assays were performed in triplicate.

In vitro generation of highly GRL-015-, -085-, and -097-resistant HIV-1 variants.

Variants resistant to GRL-015, -085, and -097 were generated as previously described (21, 30, 33). Briefly, 30 TCID50s of each of 11 highly multi-PI-resistant HIV-1 isolates (HIV-1A, HIV-1B, HIV-1C, HIV-1G, HIV-1TM, HIV-1MM, HIV-1JSL, HIV-1SS, HIV-1ES, HIV-1EV, and HIV-113–52) were mixed and propagated in a mixture of an equal number of PHA-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (5 × 105) and MT-4 cells (5 × 105), in an attempt to adapt the mixed viral population for replication in MT-4 cells. The cell-free supernatant was harvested on day 7 of coculture (PHA-PBMCs and MT-4 cells), and the supernatant obtained was designated HIV-111MIX. On the first passage, MT-4 cells (5 × 105) were exposed to HIV-111MIX or 500 TCID50s of HIV-1NL4-3, rCLHIV-1T48, or HIV-1DRVRP30 and cultured in the presence of each compound at an initial concentration equivalent to the EC50. On the last day of each passage (weeks 1 to 3), 1.5 ml of the cell-free supernatant was harvested and transferred to a culture of fresh uninfected MT-4 cells in the presence of increased concentrations of the drug for the following round of culture. In this round of culture, three drug concentrations (1-, 2-, and 3-fold higher than the previous concentration) were employed. When the replication of HIV-1 in the culture was confirmed by substantial p24 Gag protein production (greater than 200 ng/ml), the highest drug concentration among the three concentrations was used to continue the selection (for the next round of culture). This protocol was repeated until the drug concentration reached the targeted concentration. Proviral DNA samples obtained from the lysates of infected cells at selected passages were subjected to nucleotide sequencing.

Determination of nucleotide sequences.

Molecular cloning and determination of the nucleotide sequences of HIV-1 strains passaged in the presence of each compound were performed as previously described (33). In brief, high-molecular-weight DNA was extracted from HIV-1-infected MT-4 cells by using the InstaGene matrix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and was subjected to molecular cloning, followed by nucleotide sequence determination. The primers used for the first round of PCR with the entire Gag- and protease-encoding regions of the HIV-1 genome were LTR F1 (5′-GAT GCT ACA TAT AAG CAG CTG C-3′) and PR12 (5′-CTC GTG ACA AAT TTC TAC TAA TGC-3′). The first-round PCR mixture consisted of 1 μl of proviral DNA solution, 10 μl of Premix Taq (Ex Taq version; TaKaRa Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan), and 10 pmol of each of the first PCR primers in a total volume of 20 μl. The PCR conditions used were an initial 3 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 40 s at 95°C, 20 s at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C, with a final 10 min of extension at 72°C. The first-round PCR products (1 μl) were used directly in the second round of PCR with primers LTR F2 (5′-GAG ACT CTG GTA ACT AGA GAT C-3′) and Ksma2.1 (5′-CCA TCC CGG GCT TTA ATT TTA CTG GTA C-3′) under the PCR conditions of an initial 3 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 20 s at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C, with a final 10 min of extension at 72°C. The second-round PCR products were purified using spin columns (MicroSpin S-400 HR columns; Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ), cloned directly, and subjected to sequencing using a model 3130 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Protein preparation and crystallization.

Protein preparation and crystallization were carried out as previously described (20). Briefly, the wild-type (D25N) HIV-1 protease (WTPRD25N) expression vector was transformed to the Rosetta(DE3)(pLysS) strain (Novagen) by heat shock transformation. The culture was grown in a shake flask containing 30 ml of Luria broth plus kanamycin and chloramphenicol at 37°C overnight. The Luria broth culture was grown in flasks to an optical density of 0.5 at 600 nm at 37°C, and expression was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 3 h. After examination, the culture was spun down for pellet collection, and the pellets were stored at −80°C until use. For purification of WTPRD25N, each pellet was resuspended in buffer A (20 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) and lysed by sonication. The cell lysates were separated into a supernatant fraction and inclusion body fraction by centrifugation. WTPRD25N was confirmed to be present in the inclusion body fraction, which was washed five times with buffer A containing 2 M urea and then was washed with buffer A without urea. The twice-washed pellet was solubilized with 50 mM formic acid (pH 2.8). WTPRD25N was unfolded in pH 2.8 (34). The unfolded PR was refolded with the addition of a neutralizing buffer (100 mM ammonium acetate [pH 6.0], 0.005% Tween 20), shifting the final pH from 5.0 to 5.2. WTPRD25N was buffer exchanged and concentrated to 2 mg/ml in 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.0) and 0.005% Tween 20 using Amicon Ultra-15 10K centrifugal filter units (Millipore). WTPRD25N was crystallized with a 5-fold molar excess of drugs using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. Equal volumes of WTPRD25N-drug complex and well solution were mixed to a final volume of 4 μl per drop. WTPRD25N–GRL-0476 complexes were crystalized in 0.6 M sodium/potassium phosphate (pH 6.5). WTPRD25N–GRL-097 complexes were crystalized in 0.1 M sodium dihydrogen phosphate (pH 6.5), 12% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol. WTPRD25N–GRL-015 complexes were crystalized in 0.6 M sodium/potassium phosphate (pH 6.3). WTPRD25N–GRL-085 complexes were crystalized in 0.6 M sodium/potassium phosphate (pH 6.1). Crystals of WTPRD25N-drug complex were flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen after immersing the crystal into a cryoprotective solution containing well solution plus glycerol.

X-ray diffraction data collection and processing.

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the beamlines BL44XU (BeamLine 44 X-ray Undulator, insertion device) and BL41XU (BeamLine 41 X-ray Undulator, insertion device) equipped with Rayonix MX225HE-CCD detectors at the SPring-8 (Super Photon ring, 8 GeV [the power output of the ring]), Japan. Data for WTPRD25N–GRL-0476, WTPRD25N–GRL-015, and WTPRD25N–GRL-085 complexes were collected at BL44XU (source wavelength, 0.9 Å) with a frame width of 1.00° and a 1-s exposure per frame. The crystal-to-detector distances for WTPRD25N–GRL-0476, WTPRD25N–GRL-015, and WTPRD25N–GRL-085 complexes were 189 mm, 175 mm, and 189 mm, respectively. Data for the WTPRD25N–GRL-097 complex were collected at a BL41XU (source wavelength, 1.0 Å) with a frame width of 1.00° and a 1-s exposure per frame. The crystal-to-detector distance for the WTPRD25N–GRL-097 complex was 175 mm. Diffraction data were processed and scaled using HKL2000 (35). X-ray diffraction data processing details are given in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Structure solutions and refinement.

Structure solutions were obtained using the molecular replacement (MR) method as described previously (36, 37). Briefly, MR was performed using MOLREP (38) through the CCP4 (39, 40) interface with WTPR taken from PDB ID 4HLA as a search model. Structure solutions were directly refined using REFMAC5 (41) through the CCP4 interface. The initial coordinates for GRL-0476, GRL-015, GRL-085, and GRL-097 were prepared by modifying the structure of TMC-126 taken from the crystal structure, PDB ID 2I4U. The PIs were fitted into the electron density using the automated refinement and weighted automated refinement procedures (ARP/wARP) through the CCP4 interface (42, 43). Initial refinement libraries for GRL-0476, GRL-015, GRL-085, and GRL-097 were obtained from REFMAC. Solvent molecules were built using ARP/wARP solvent building module through the CCP4 interface. After water molecules had been built, the final models were refined using the simulated annealing method from phenix.refine (PHENIX, version 1.9-1692) (44) on the NIH-Biowulf Linux cluster. The root mean square deviation in bond lengths and bond angles of ligands was significantly improved by employing geometry-optimized libraries using the semiempirical quantum mechanical method of refinement, eLBOW-AM1 (45), during refinement in phenix.refine. Details of the refinement statistics are given in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Structural analysis.

The final refined structures were used for structural analysis. Hydrogen bonds were calculated by using cutoff values for distance (the maximum distance between the donor and acceptor heavy atoms is 3.0 Å) and angles (minimum donor, 90°; minimum acceptor, 60°). Hydrogen bonds with a distance of >3.0 Å were considered weak interactions. Hydrophobic contacts were calculated between two carbon atoms (one from PI and one from WTPRD25N) with a maximum 4-Å distance cutoff.

Generation of FRET-based HIV-1 expression system.

The intermolecular fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based HIV-1-expression assay employing cyan and yellow fluorescent protein-tagged protease monomers (CFP and YFP, respectively) was carried out as previously described (18). In brief, CFP- and YFP-tagged HIV-1 protease constructs were generated using BD Creator DNA cloning kits (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For the generation of full-length molecular infectious clones containing CFP- or YFP-tagged protease, the PCR-mediated recombination method was used (46). A linker consisting of five alanines was inserted between protease and fluorescent proteins. The phenylalanine-proline site that HIV-1 protease cleaves was also introduced between the fluorescent protein and reverse transcriptase. Thus, the DNA fragments obtained were subsequently joined by using the PCR-mediated recombination reaction performed under the standard condition for ExTaq polymerase (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan). The amplified PCR products were cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO vector according to the manufacturer's instructions (Gateway cloning system; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PCR products were generated with pCR-XL-TOPO vector as the template, followed by digestion by both ApaI and XmaI, and the ApaI-XmaI fragment was introduced into pHIV-1NLSma, generating pHIV-PRWTCFP and pHIV-PRWTYFP.

FRET procedure.

COS7 cells plated on EZ View cover, glass-bottom culture plates (Iwaki, Tokyo) were transfected with pHIV-PRWTCFP and pHIV-PRWTYFP using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions in the presence of various concentrations of each compound, cultured for 72 h, and analyzed under a Fluoview FV500 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus Optical Corp., Tokyo, Japan) at room temperature as previously described (18). When the effect of each compound was analyzed with FRET, test compounds were added to the culture medium simultaneously with plasmid transfection. Results of FRET were determined by quenching of CFP (donor) fluorescence and an increase in YFP (acceptor) fluorescence (sensitized emission), since a part of the energy of CFP is transferred to YFP instead of being emitted. The changes in the CFP and YFP fluorescence intensity in the images of selected regions were examined and quantified using Olympus FV500 Image software system (Olympus Optical Corp.). Background values were obtained from the regions where no cells were present and were subtracted from the values for the cells examined in all calculations. Ratios of intensities of CFP fluorescence after photobleaching to CFP fluorescence prior to photobleaching (CFPA/B ratios [18]) were determined. It is well established that CFPA/B ratios greater than 1.0 indicate that association of CFP- and YFP-tagged proteins occurred, and it was inferred that the dimerization of protease subunits occurred. A CFPA/B ratio less than 1 indicated that the association of the two subunits did not occur, and it was inferred that protease dimerization was inhibited (18).

Protein structure accession numbers.

The final refined coordinates for the crystal structures of WTPRD25N–GRL-0476, WTPRD25N–GRL-015, WTPRD25N–GRL-085, and WTPRD25N–GRL-097 complexes were deposited in the worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB) under accession IDs 5COK, 5CON, 5COO and 5COP, respectively.

RESULTS

GRL-015, -085, and -097 exert potent activity against wild-type HIV-1LAI and HIV-2ROD.

We designed, synthesized, and identified three novel protease inhibitors (PIs), GRL-015, -085, and -097, which exert potent anti-HIV activity against various HIV-1 strains. These three PIs have in common a tetrahydropyrano-tetrahydrofuran (Tp-THF) moiety with a hydroxyl at the C-5 position of the Tp-THF (Fig. 1A). In addition, GRL-085 and -097 carry a methoxy moiety in their P1 benzene ring. Of note, DRV does not contain a hydroxyl in its bis-THF moiety at the P2 site or a methoxy in its P1 benzene ring (Fig. 1B). Also, GRL-015 and -085 have a methoxybenzene moiety at their P2′ site, while GRL-097 and DRV contain an aminobenzene at the P2′ site.

As shown in Table 1, all three PIs (GRL-015, GRL-085, and GRL-097) showed potent antiviral activity against wild-type HIV-1LAI, with EC50s of 3.2 ± 1.5, 3.0 ± 1.3, and 49 ± 21 nM, and against HIV-2ROD, with EC50s of 1.6 ± 0.6, 2.4 ± 0.6, and 42 ± 19 nM, respectively, as examined in the MTT assay using CD4+ MT-2 cells as target cells. Notably, the 3 PIs were more potent than four FDA-approved PIs—APV, LPV, ATV, and TPV—and as potent as DRV (Table 1). Moreover, all three PIs had favorable cytotoxicity profiles. GRL-015 had a CC50 of 80 μM, and GRL-085 and -097 had CC50s of >100 μM (Table 1), giving selectivity index (SI) values of 25,000, >33,333, and >2,040, respectively (Table 1). On the other hand, GRL-012, whose structure is equivalent to that of TMC310911 (31) (Fig. 1C), was potent against HIV-1LAI and HIV-2ROD but turned out to be more toxic to the cells, with an SI value of 1,636 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Antiviral activity of GRL-015, -085, and -097 against HIV-1LAI and HIV-2ROD and their cytotoxicities in vitroa

| Drug | Mean EC50 (μM) ± SD |

CC50 (μM)b | Selectivity indexc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1LAI | HIV-2ROD | |||

| APV | 35 ± 12 | 180 ± 30 | >100 | >2,857 |

| LPV | 18 ± 8 | 16 ± 5 | 28 | 1,555 |

| ATV | 4.8 ± 2.3 | 14 ± 6 | 29 | 6,041 |

| TPV | 330 ± 30 | 1,300 ± 200 | 57 | 172 |

| DRV | 2.8 ± 10 | 3.7 ± 1.6 | 90 | 32,142 |

| GRL-012 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 3.6 | 1,636 |

| GRL-015 | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 80 | 25,000 |

| GRL-085 | 3.0 ± 1.3 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | >100 | >33,333 |

| GRL-097 | 49 ± 21 | 42 ± 19 | >100 | >2,040 |

All assays were conducted in duplicate, and the data are means ± 1 standard deviation, derived from the results of three independent experiments.

The concentration required to reduce the number of the cells by 50% compared to that of drug-unexposed controls.

Ratio of CC50 to EC50 against HIV-1LAI.

GRL-015, -085, and -097 exert potent antiviral activity against various in vitro PI-selected HIV-1 variants and multidrug-resistant clinical HIV-1 isolates.

We next examined whether GRL-015, -085, and -097 were active against a variety of HIV-1 variants that had been selected in vitro with each of six FDA-approved PIs: APV, LPV, ATV, SQV, TPV, and DRV (Table 2). Each HIV-1 variant was selected in vitro by increasing concentrations of each PI and propagating a wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 for APV, LPV, ATV, and SQV (21, 33) and a mixture of eight or 11 highly multiple-PI-resistant HIV-1 variants for TPV and DRV (21, 30). Those variants were confirmed to have acquired multiple amino acid substitutions in their protease region, which have reportedly been associated with viral resistance to PIs (Table 2, footnote b). Each of the PI-selected variants (HIV-1APV-5μM, HIV-1LPV-5μM, HIV-1ATV-5μM, HIV-1DRVRP30, HIV-1DRVRP40, and HIV-1DRVRP51) was highly resistant to the corresponding PI, which the variant was selected against, and the differences in the EC50s relative to the EC50 of each drug against HIV-1NL4-3 ranged from >41- to 1,022-fold (Table 2). Both HIV-1SQV-5μM and HIV-1TPV-15μM were also significantly resistant to the FDA-approved PIs examined in the present study (Table 2). Although the three nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) (AZT, 3TC, and TDF) were active against HIV-1NL4-3, they had greatly reduced activity for HIV-1DRVRP30 and HIV-1DRVRP51, since both HIV-1DRVRP30 and HIV-1DRVRp51P were derived from a mixed population of clinical HIV-1 strains isolated from heavily NRTI-experienced AIDS patients. As expected, an integrase inhibitor, DTG, showed highly potent activity against HIV-1NL4-3, HIV-1DRVRP30, and HIV-1DRVRp51P, since none of such patients had received DTG. However, all four novel PIs (GRL-012, -015, -085, and -097) were active against all the five in vitro-selected HIV-1 variants except DRV-selected resistant viruses, with differences in EC50s ranging from 0.4- to 11-fold (Table 2). It was noted that GRL-012 and -015 had less activity against the two in vitro DRV-selected variants (HIV-1DRVRP40 and HIV-1DRVRP51), with the differences in EC50s ranging from 30- to 69-fold. However, GRL-085 and -097 remained substantially active against HIV-1DRVRP40 and HIV-1DRVRP51, with the differences in EC50s ranging from only 6- to 13-fold (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Antiviral activities of GRL-015, -085, and -097 against in vitro PI-selected HIV-1 variantsa

| Viral variant | Mean EC50 (nM) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRL-015 | GRL-085 | GRL-097 | GRL-012 | APV | LPV | ATV | DRV | AZT | 3TC | TDF | DTG | |

| HIV-1NL4-3 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 46 ± 21 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 25 ± 2 | 12 ± 1 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 21 ± 7 | 420 ± 230 | 490 ± 190 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| HIV-1APV-5μM | 2.6 ± 0.8 (0.8) | 1.9 ± 0.2 (0.6) | 18 ± 4 (0.4) | 17 ± 3.2 (5.3) | >1,000 (>41) | 230 ± 18 (19) | 2.4 ± 0.7 (0.9) | 198 ± 21 (70) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| HIV-1LPV-5μM | 2.5 ± 0.5 (0.7) | 2.6 ± 0.4 (0.8) | 32 ± 3 (0.7) | 2.1 ± 1.1 (0.6) | 340 ± 40 (14) | >1,000 (>83) | 36 ± 9 (14) | 28 ± 6 (10) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| HIV-1ATV-5μM | 2.3 ± 0.4 (0.7) | 2.4 ± 0.6 (0.8) | 29 ± 4 (0.6) | 1.2 ± 0.7 (0.4) | 480 ± 10 (20) | 360 ± 50 (30) | >1,000 (>385) | 4.8 ± 0.4 (1.7) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| HIV-1SQV-5μΜ | 2.8 ± 0.1 (0.8) | 2.7 ± 0.5 (0.8) | 30 ± 3 (0.7) | 3.0 ± 0.1 (0.9) | 365 ± 22 (15) | >1,000 (>83) | 430 ± 20 (165) | 15 ± 10 (5.3) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| HIV-1TPV-15μM | 3.4 ± 0.4 (1.0) | 3.9 ± 0.7 (1.2) | 210 ± 20 (5) | 34 ± 6 (11) | >1,000 (>41) | >1,000 (>83) | >1,000 (>385) | 33 ± 1 (12) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| HIV-1DRVRP30 | 16 ± 3 (4.7) | 2.8 ± 0.2 (0.9) | 28 ± 3 (0.6) | 1.2 ± 0.1 (0.4) | >1,000 (>41) | >1,000 (>83) | >1,000 (>385) | 222 ± 31 (80) | >1,000 (>48) | >1,000 (>2.4) | >1,000 (>2) | 0.3 ± 0.1 (0.8) |

| HIV-1DRVRP40 | 230 ± 40 (69) | 29 ± 6 (9) | 280 ± 40 (6) | 66 ± 23 (30) | >1,000 (>41) | >1,000 (>83) | >1,000 (>385) | 2,500 ± 500 (910) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| HIV-1DRVRP51 | 220 ± 20 (68) | 42 ± 1 (13) | 310 ± 60 (6.8) | 170 ± 30 (53) | >1,000 (>41) | >1,000 (>83) | >1,000 (>385) | 2,800 ± 300 (1022) | >1,000 (>48) | >1,000 (>2.4) | >1,000 (>2) | 0.3 ± 0.5 (0.8) |

The amino acid substitutions identified in protease of HIV-1APV-5μM, HIV-1LPV-5μM, HIV-1ATV-5μM, HIV-1SQV-5μM, HIV-1TPV-15μM, HIV-1DRVRP30, HIV-1DRVRP40, and HIV-1DRVRP51 compared to the wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 include L10F/V32I/L33F/M46L/I54M/A71V, L10F/V32I/M46I/I47A/A71V/I84V, L23I/E34Q/K43I/M46I/I50L/G51A/L63P/A71V/V82A/T91A, L10I/N37D/G48V/I54V/L63P/G73C/I84V/L90M, L10I/L33I/M36I/M46I/I54V/K55R/I62V/L63P/A71V/G73S/V82T/L90M/I93L, L10I/I15V/K20R/L24I/V32I/M36I/M46L/L63P/K70Q/V82A/I84V/L89M, L10I/I15V/K20R/L24I/V32I/L33F/M36I/R41K/M46L/I54M/L63P/K70Q/V82A/I84V/L89M, and L10I/I15V/K20R/L24I/V32I/L33F/M36I/M46L/I54M/L63P/K70Q/V82I/I84V/L89M, respectively. Numbers in parentheses are fold changes in EC50 for each isolate compared to the EC50 for wild-type HIV-1NL4-3. All assays were conducted in triplicate, and the data are means ± 1 standard deviation derived from the results of three independent experiments. ND, not determined.

We also determined the activities of GRL-012, -015, -085, and -097 against seven recombinant clinical HIV-1 isolates (rCLHIV-1F16, rCLHIV-1F39, rCLHIV-1V42, rCLHIV-1V44, rCLHIV-1T45, rCLHIV-1T48, and rCLHIV-1F71), which contained 16 to 23 PI resistance-associated amino acid substitutions in their protease regions (Table 3, footnote a). The changes in the EC50s of APV and LPV against the rCLHIV-1 isolates were mostly >41-fold and >83-fold, respectively, and the activities of other two PIs, ATV and DRV, had also been significantly compromised, with changes of EC50s of 62- to 249-fold (Table 3). However, GRL-015, -085, and -097 still remained active against all of the multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants examined, and the changes were as low as 0.7- to 10-fold (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Antiviral activity of GRL-015, -085, and -097 against recombinant multidrug-resistant infectious HIV-1 clonesa

| Virus | Mean EC50 (nM) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRL-015 | GRL-085 | GRL-097 | GRL-012 | APV | LPV | ATV | DRV | |

| HIV-1NL4-3 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 46 ± 21 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 25 ± 2 | 12 ± 1 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.4 |

| rCLHIV-1F16 | 16 ± 8 (4.8) | 12 ± 9 (3.9) | 34 ± 2 (0.7) | 29 ± 17 (9.2) | >1,000 (>41) | >1,000 (>83) | 180 ± 18 (69) | 308 ± 84 (111) |

| rCLHIV-1F39 | 16 ± 7 (4.8) | 4.0 ± 0.5 (1.2) | 32 ± 9 (0.7) | 13 ± 4 (4.2) | >1,000 (>41) | >1,000 (>83) | 270 ± 3 0 (105) | 323 ± 62 (116) |

| rCLHIV-1V42 | 19 ± 8 (5.7) | 3.7 ± 0.4 (1.2) | 320 ± 20 (7.0) | 32 ± 2 (10) | >1,000 (>41) | >1,000 (>83) | 270 ± 20 (105) | 305 ± 20 (110) |

| rCLHIV-1T44 | 29 ± 6 (8.8) | 29 ± 4 (9.0) | 340 ± 40 (7.3) | 140 ± 40 (44) | 350 ± 30 (14) | >1,000 (>83) | 650 ± 110 (249) | 210 ± 90 (75) |

| rCLHIV-1M45 | 33 ± 8 (10) | 32 ± 8 (10) | 280 ± 60 (6.0) | 32 ± 7 (10) | >1,000 (>41) | >1,000 (>83) | 520 ± 19 (200) | 327 ± 71 (117) |

| rCLHIV-1T48 | 6.7 ± 4.3 (2.0) | 3.6 ± 0.5 (1.1) | 28 ± 1 (0.6) | 2.0 ± 0.8 (0.6) | >1,000 (>41) | >1,000 (>83) | 440 ± 20 (169) | 170 ± 10 (62) |

| rCLHIV-1F71 | 12 ± 14 (3.6) | 16 ± 11 (4.9) | 40 ± 4 (0.9) | 17 ± 3 (5.3) | >1,000 (>41) | >1,000 (>83) | 530 ± 20 (204) | 300 ± 120 (109) |

The amino acid substitutions identified in protease of rCLHIV-1F16, rCLHIV-1F39, rCLHIV-1V42, rCLHIV-1T44, rCLHIV-1M45, rCLHIV-1T48, and rCLHIV-1F71 compared to the wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 include L10F/V11I/I13V/L19Q/K20M/V32I/L33V/E35A/M36I/M46I/I47V/I54M/R57K/I62V/L63P/I64V/G73T/T74A/I84V/L89V/L90M, L10V/V11I/I13V/K14R/I15V/K20T/V32I/L33F/M36I/R41K/M46L/I54L/R57K/D60E/L63P/G68E/K70T/A71I/I72M/G73S/I84V/L89V/L90M/I93I, L10V/T12V/I13V/I15V/K20M/V32I/L33F/K43T/M46I/I47V/I54M/D60E/Q61N/I62V/L63P/C67Y/H69K/A71I/I72LG73S/V77I/V82A/L89V/L90M, L10F/I13V/G16A/L19V/L33F/E34Q/K43I/M46L/G51A/I54M/L63P/I64M/A71V/I72M/G73A/I84V/L90M, L10F/V11I/T12P/I13V/I15V/L19P/K20T/V32I/L33F/E35G/M36I/I54V/I62V/L63P/K70T/A71V/G73S/P79A/I84VL89V//L90M, L10I/I13V/I15V/L19V/L24I/V32I/L33F/K43E/M46L/I54L/D60E/L63P/A71V/I72V/V82A/I84V, and L10I/V11I/T12K/I13V/K20V/V32I/L33F/E35G/M36I/N37D/M46L/I47V/I54M/R57K/Q58E/L63P/I64V/I66V/A71V/G73S/I84V/L89M/L90M, respectively. Numbers in parentheses are fold changes in IC50s for each isolate compared to the EC50s for wild-type HIV-1NL4-3. All assays were conducted in triplicate, and the data are means ± 1 standard deviation derived from the results of three independent experiments.

The C-5 hydroxyl moiety of Tp-THF is critical for the potent antiviral activity of GRL-015, -085, and -097 against multi-PI-resistant HIV-1 variants.

In order to examine the potent activity of GRL-015, -085, and -097 against multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants, we employed a compound, GRL-0476, which has a structure identical to that of GRL-015 but lacks the hydroxyl moiety at the C-5 position in its Tp-THF (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, the antiviral activities of GRL-0476 against HIV-1DRVRP20 and HIV-1DRVRP30 were significantly reduced, with changes of 64-fold and 98-fold, respectively (Table 4). Moreover, two PIs (GRL-034 and -087) carrying bis-THF with a hydroxyl moiety at the C-4 position (Fig. 1B), also potently inhibited the replication of HIV-1DRVRP20 and HIV-1DRVRP30, with changes ranging from 0.7- to 1.1-fold, although DRV and TMC126, lacking a C-4 hydroxyl in their bis-THF, had less activity against the two variants (Fig. 1B and Table 4), strongly suggesting that the presence of the hydroxyl moiety at C-5 in Tp-THF and C4 in bis-THF is critical for inhibiting the replication of multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants.

TABLE 4.

Antiviral activity of compounds with or without the OH moiety at C-5 of Tp-THF or C-4 of bis-THF against DRV-resistant HIV-1 variantsa

| Virus | Mean EC50 (nM) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tp-THF |

bis-THF |

|||||

| GRL-0476 | GRL-015 | DRV | TMC126 | GRL-034 | GRL-087 | |

| HIV-1NL4-3 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 260 ± 70 | 27 ± 4 |

| HIV-1DRVRP20 | 270 ± 120 (64) | 3.3 ± 0.3 (1.0) | 36 ± 1 (13) | 19 ± 5 (70) | 269 ± 7 (1.1) | 30 ± 2 (1.1) |

| HIV-1DRVRP30 | 420 ± 60 (98) | 16 ± 3 (4.7) | 222 ± 31 (80) | 176 ± 62 (645) | 197 ± 37 (0.8) | 20 ± 3 (0.7) |

The amino acid substitutions identified in protease of HIV-1DRVRP20 compared to the wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 include L10I/I15V/K20R/L24I/V32I/M36I/M46L/L63P/A71T/V82A/L89M. Numbers in parentheses are fold changes in EC50s for each isolate compared to the EC50s for wild-type HIV-1NL4-3. All assays to determine the EC50s were conducted in duplicate or triplicate, and the data are means ± 1 standard deviation derived from the results of three independent assays.

The C-5 hydroxyl moiety in Tp-THF forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of Gly48.

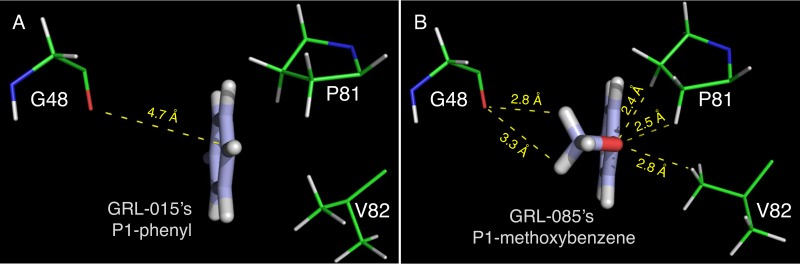

The X-ray crystal structures of wild-type (D25N) HIV-1 protease in complex with GRL-0476, -015, -085, and -097 were solved in the space group P61 with one protease dimer per asymmetric unit (Fig. 2 and 3). The Tp-THF moiety of all four inhibitors showed strong H bonds, with the polar hydrogen atoms associated with the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of D29 and D30 in a fashion similar to that of the bis-THF moiety of DRV (37) (PDB ID 4HLA) (Fig. 2). The average distance between the oxygen atom of the tetrahydropyran ring from the inhibitors' Tp-THF moiety and the polar hydrogen atom associated with the backbone amide nitrogen atom of D30 was found to be 2.2 Å, while the distance between the oxygen atom of the furan ring from the inhibitors' Tp-THF moiety and the polar hydrogen atom associated with the backbone amide nitrogen atom of D29 was found to be 1.8 Å. Additionally, the C-5 hydroxyl group from the Tp-THF moiety of GRL-015, -085, and -097 showed one strong H bond with the carbonyl oxygen atom of G48, in the corresponding crystal structures, with an average interatomic distance of 2.5 Å. The crystal structure of GRL-097 with protease shows an additional water molecule which is stabilized by a polar contact from the hydroxyl group attached to the C-5 atom of the Tp-THF moiety (Fig. 2D). In the case of GRL-0476, the hydrogen atom associated with the C-5 atom of Tp-THF was found to be 2.7 Å from the carbonyl oxygen atom of G48 (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the hydrogen atom attached to the C-5 atom of bis-THF (the P2-moiety of DRV; PDB ID 4HLA) was found to be 2.5 Å from the carbonyl oxygen atom of G48. The P2′ moieties (methoxybenzene) of GRL-0476, -015, and -085 show one strong H bond each with the polar hydrogen atom associated with the backbone amide nitrogen atom of D30′, with an average interatomic distance of 2.9 Å. In the case of GRL-097, the P2′ aniline moiety showed a strong H bond with the δ-oxygen atom from the side chain of D30′, with an interatomic distance of 2.1 Å, while the P2′ aniline moiety of DRV was found to be at an average distance of 2.5 Å from either the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of D30′ or the δ-oxygen atom from the side chain of D30′. All four inhibitors showed a strong H bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of G27, with an average interatomic distance of 2.5 Å, while in the case of DRV, this distance was found to be 2.3 Å. At least one H bond each with the side chains of N25 and N25′ was seen for all four inhibitors originating from the transition state mimic hydroxyl group, as was seen in the case of DRV. A conserved crystallographic water molecule was seen in all four crystal structures, with bridging H bonds between each inhibitor and the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of I50 and I50′. The methoxy group at the P1 site of GRL-085 has improved nonbonded interactions with G48, P81, and V82 (Fig. 3).

FIG 2.

X-ray crystal structures of HIV-1 protease complexed with GRL-0476, -015, -085, or -097. The profiles of polar contacts made by GRL-0476 (A), -015 (B), -085 (C), and -097 (D) with WTPRD25N are shown. In each structure, the inhibitor is bound in two alternate orientations with average occupancies of 0.49 and 0.51. In order to analyze the hydrogen bonds (H bonds), hydrogen atoms were added and their orientations were optimized sampling the crystallographic water molecules through the protein preparation wizard in Maestro (v9.0 Schrodinger LLC.). In each panel, the carbon atoms for the protease inhibitors are in white, while the carbon atoms of WTPRD25N are in green. Nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur atoms are in blue, red, and yellow, respectively. Crystallographic water molecules are shown as red spheres.

FIG 3.

The P1 methoxybenzene moiety of GRL-085 shows improved nonbonded interactions. The P1 phenyl moiety of GRL-015 (A) and P1 methoxybenzene moiety of GRL-085 (B) are shown (thick-stick representation). In both panels, the carbon atoms of the PIs are in light blue, hydrogens are in white, and oxygen is in red. The carbon atoms of the corresponding protease amino acid residues (thin-stick representation) are in green, nitrogen atoms are in blue, oxygen atoms are in red, and hydrogen atoms are in white.

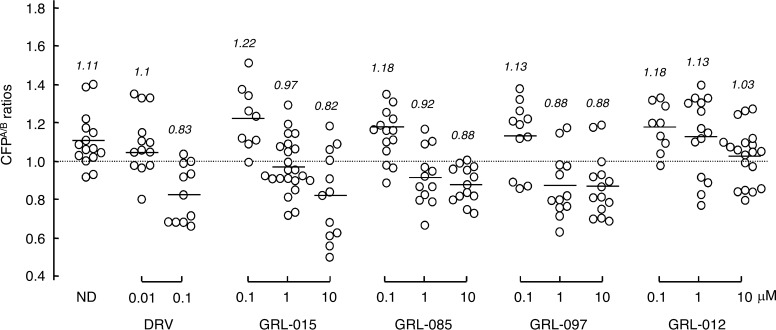

GRL-015, -085, and -097 disrupt the dimerization of HIV-1 protease.

We previously reported that DRV effectively disrupts the dimerization of HIV-1 protease monomer subunits, as determined by the FRET-based HIV-1 expression assay (18, 19). We therefore sought to determine whether GRL-015, -085, and -097 exerted protease dimerization inhibition activity. In the absence of drug, the mean CFPA/B ratio obtained was 1.11, indicating that protease dimerization clearly occurred (Fig. 4). However, the ratio decreased to 0.83 in the presence of 0.1 μM DRV, indicating that DRV blocked the dimerization of the protease subunit (Fig. 4). In the presence of 0.1 μM GRL-015, -085, and -097, the mean CFPA/B ratios were 1.22, 1.18, and 1.13, respectively, showing that these PIs failed to block the protease dimerization. However, the mean CFPA/B ratios obtained in the presence of 1 and 10 μM GRL-015, -085, and -097 were all less than 1.0, indicating that these three PIs blocked dimerization (Fig. 4). Of note, GRL-012, on the other hand, was not capable of inhibiting protease dimerization even at concentrations up to 10 μM (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Inhibition of HIV-1 protease dimerization. COS7 cells were exposed to each of the agents (GRL-015, -085, -097, and -012 and DRV) at various concentrations (0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 μM) and subsequently cotransfected with plasmids encoding full-length molecular infectious HIV-1 (HIVNL4-3) clones, producing CFP- or YFP-tagged protease. After 72 h, cultured cells were examined in the FRET-based HIV-1 expression assay, and the CFPA/B ratios (y axis) were determined. The mean values of the ratios obtained are shown as horizontal bars. A CFPA/B ratio greater than 1 signifies that protease dimerization occurred, whereas a ratio less than 1 signifies the disruption of protease dimerization. All the experiments were conducted in a blinded fashion. Statistical differences were as follows: for the CFPA/B ratios in the absence of drug (CFPA/BNo Drug) versus the CFPA/B ratios in the presence of 0.01 μM DRV (CFPA/B0.01 DRV), P = 0.5846; for CFPA/BNo Drug versus CFPA/B0.1 DRV, P = 0.0002; for CFPA/BNo Drug versus CFPA/B0.1 GRL-015, P = 0.1784; for CFPA/BNo Drug versus CFPA/B1 GRL-015, P = 0.0021; for CFPA/BNo Drug versus CFPA/B0.1 GRL-085, P = 0.2006; for CFPA/BNo Drug versus CFPA/B1 GRL-085, P = 0.0033; for CFPA/BNo Drug versus CFPA/B0.1 GRL-097, P = 0.4482; for CFPA/BNo Drug versus CFPA/B1 GRL-097, P = 0.0006; for CFPA/BNo Drug versus CFPA/B1 GRL-012, P = 0.1189; and for CFPA/BNo Drug versus CFPA/B10 GRL-012, P = 0.0007.

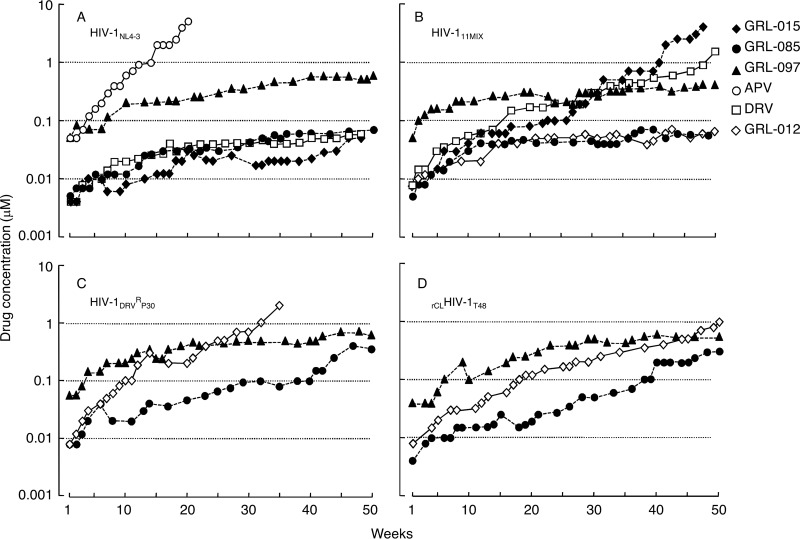

Failure of in vitro selection of HIV-1 variants resistant to GRL-015, -085, and -097 using HIV-1NL4-3 as a starting HIV-1 population.

We attempted to select HIV-1 variants resistant to GRL-015, -085, and -097 by propagating HIV-1NL4-3 in MT-4 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of each PI (Fig. 5A). When selected in the presence of APV, the virus quickly became resistant to the drug and started replicating in the presence of 5 μM by 20 weeks (HIVNL4-3APV-WK20) (Fig. 5A). The protease-encoding region of the virus obtained from the culture concluding at week 20 contained seven amino acid substitutions, which were thought to be associated with the acquisition of HIV-1 resistance against APV (Fig. 6A). However, the development of DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants was significantly delayed, and the concentration of DRV that allowed the virus to replicate was as low as 0.07 μM by 50 weeks. HIVNL4-3DRV-WK50 had accumulated only two amino acid substitutions, K45I and V82I, in the protease-encoding region (Fig. 5A and 6A). Of note, HIV-1NL4-3 failed to propagate in the presence of more than 0.05 μM GRL-015, >0.07 μM GRL-085, and >0.55 μM GRL-097 until 50 weeks of selection, as has been seen in the case of DRV (21) (Fig. 5A).

FIG 5.

In vitro selection of HIV-1 variants against GRL-015, -085, and -097. HIV-1NL4-3 (A), a mixture of 11 multi-PI-resistant HIV-1 isolates (HIV-111MIX) (B), a DRV-resistant HIV-1 variant obtained from in vitro passage 30 with DRV (HIV-1DRVRP30) (C), and an infectious molecular HIV-1 clone derived from heavily treated HIV-1-infected patient (rCLHIV-1T48) (D) were propagated in the presence of increasing concentrations of each agent in MT-4 cells. The selection was carried out in a cell-free manner by 50 weeks escalating from the EC50 of the compounds for each virus.

FIG 6.

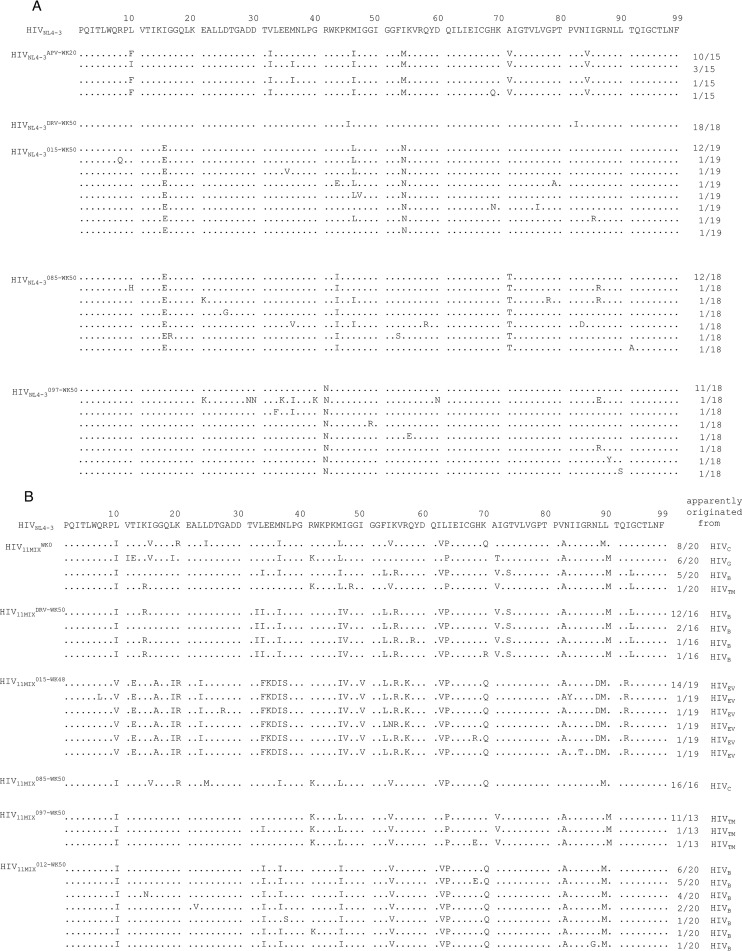

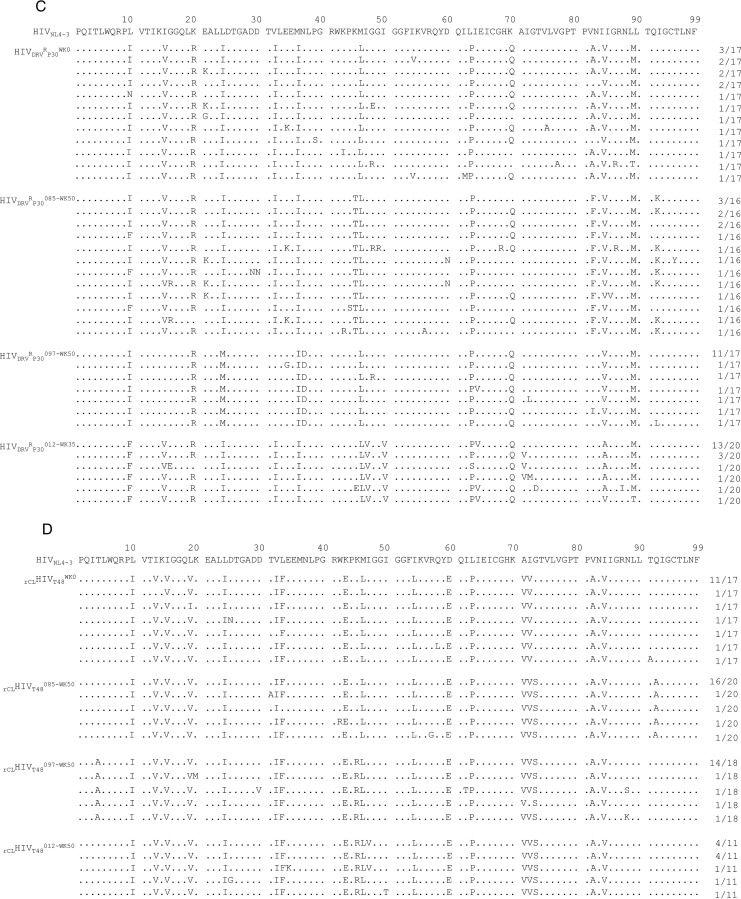

Amino acid sequences of the protease-encoding regions of HIV-1NL4-3, HIV-111MIX, HIV-1DRVRP30, and rCLHIV-1T48 in vitro, selected with various agents. Shown are the amino acid sequences deduced from the nucleotide sequences of the protease-encoding region of proviral DNA isolated from HIV-1NL4-3 at week 20 with APV and at week 50 with DRV or GRL-015, -085, or -097 (A); HIV-111MIX at week 0 and week 50 with DRV or GRL-015, -085, -097, or -012 (B); HIV-1DRVRP30 at week 0 and week 35 with GRL-012 and at week 50 with GRL-085 or -097 (C); and rCLHIV-1T48 at week 0 and week 50 with GRL-085, -097, or -012 (D). The consensus sequence of HIV-1NL4-3 is at the top as a reference. Identity with sequence at individual amino acid positions is indicated by dots. The fractions on the right are the number of viruses which each clone is presumed to have originated from over the number of clones examined.

In vitro selection of HIV-1 variants resistant to GRL-015, -085, and -097 using HIV-111MIX, HIV-1DRVRP30, and rCLHIV-1T48 as a starting HIV-1 population.

We previously reported that the use of a mixture of 8 or 11 mult-PI-resistant clinical HIV-1 isolates, HIV-18MIX or HIV-111MIX, as a starting HIV-1 population makes it possible to rapidly obtain highly DRV- or TPV-resistant HIV-1 variants (21, 30). We therefore employed HIV-111MIX to possibly obtain resistant HIV-1 variants against GRL-015, -085, and -097 (Fig. 5B). The concentrations of DRV and GRL-015 that allowed HIV-111MIX to propagate reached 2 and 4 μM by 50 and 48 weeks of selection, respectively (Fig. 5B). In HIV11MIXDRV-WK50 and HIV11MIX015-WK48, HIVB and HIVEV, which constituted a part of HIV11MIX, were found to have apparently dominated at the conclusion of 50 and 48 weeks of selection, respectively (Fig. 6B). In fact, HIV11MIXDRV-WK50 contained almost all the amino acid substitutions that HIVB originally had and an additional three amino acid substitutions, K14R, V32I, and I47V, in its protease-encoding region (Fig. 6B; also, see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). HIV11MIX015-WK48 contained almost all the amino acid substitutions that HIVEV originally had and an additional 10 amino acid substitutions, L23I, E34K, N37S, I47V, V54I, E60D, K70Q, V71A, N88D, and Q92R, in its protease-encoding region (Fig. 6B; also, see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

In contrast, the development of viral resistance to GRL-085 and -097 was significantly delayed even when HIV-111MIX was used as a starting HIV-1 population. The concentrations of GRL-085 and GRL-097 were as low as 0.055 μM and 0.55 μM even at the conclusion of 50 weeks of selection (Fig. 5B). The development of resistance to GRL-012 was also significantly delayed. The apparently dominant viral populations in HIV11MIX085-WK50, HIV11MIX097-WK50, and HIV11MIX012-WK50 were HIVC, HIVTM, and HIVB, respectively (Fig. 6B); however, the virological significance of these findings is not known.

Finally, we employed HIV-1DRVRP30 and rCLHIV-1T48 as a starting virus population for the selection of HIV-1 resistant against GRL-012, -085, and -097 (Fig. 5C and D). By 35 weeks of selection, HIV-1DRVRP30 was propagating in the presence of 2 μM GRL-012 and had acquired additional five amino acid substitutions, I47V, I50V, I64V, A82V, and V84A, in its protease-encoding region (Fig. 5C and 6C). By 50 weeks of selection, rCLHIV-1T48 was propagating in the presence of 1 μM GRL-012 and contained two additional amino acid substitutions, K45R and G73S (Fig. 5D and 6D). In contrast, HIV-1DRVRP30 did not propagate well in the presence of increasing concentrations of GRL-085 and -097, which reached only 0.35 and 0.6 μM, respectively, at 50 weeks of selection. HIVDRVRP30085-WK50 had acquired only three additional amino acid substitutions, K45T, V82F, and Q92K, while HIVDRVRP30097-WK50 had acquired four additional 4 substitutions, V15I, I32V, N37D, and A82V (Fig. 6C). The recombinant virus rCLHIV-1T48 also failed to propagate well in the presence of GRL-085 and -097, which reached concentrations as low as 0.3 μM and 0.55 μM, respectively, at the end of 50 weeks of selection (Fig. 5D). The variants rCLHIVT48085-WK50 and rCLHIVT48097-WK50 had acquired only a few substitutions, G73S and Q92A for the former and T4A, K45R, and G73S for the latter (Fig. 6D).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we designed, synthesized and identified three novel PIs, GRL-015, -085, and -097, containing a Tp-THF moiety with a hydroxyl at the C-5 position (Fig. 1) which exhibit comparable or more potent antiviral activity against wild-type HIV-1LAI as well as favorable cytotoxicity in vitro compared to four representative FDA-approved PIs, APV, LPV, ATV, and DRV (Table 1). Furthermore, the three compounds also potently inhibited the replication of HIV-2ROD, despite the fact that HIV-2 originally has various PI-related resistance mutations, such as V32I and I47V, as polymorphisms (47).

The latest FDA-approved protease inhibitor, DRV, potently inhibits the replication of multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants (13–15) and has a high genetic barrier against HIV's development of drug resistance (16–19). However, the emergence of DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants has been reported in in vitro and in vivo (21–26); hence, more potent PIs are needed to intercept the replication of such DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants. In regard to in vitro DRV-selected HIV-1 variants, we previously selected highly DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants using a mixture of 8 multidrug-resistant HIV-1 strains in vitro (21), which had significantly reduced sensitivity against all of four FDA-approved PIs, DRV as well as APV, LPV, and ATV, as illustrated in Table 2. In the present study, we also employed three highly DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants (HIV-1DRVRP30, HIV-1DRVRP40, and HIV-1DRVRP51) (21). As previously described (21), all of these variants were significantly less susceptible to DRV (Table 2). In particular, HIV-1DRVRP51, which contains a unique combination of amino acid substitutions (V32I, L33F, I54M, and I84V) in its protease region that is responsible for HIV-1's DRV resistance (21), was 1,022 times less susceptible to DRV than wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 (Table 2). Although V82I is present in HIV-1DRVRP51 and emerged in HIVNL4-3DRV-WK50 (Fig. 6A), HIV-1NL4-3 carrying V82I was still sensitive to DRV, with an EC50 of 4 nM (data not shown). However, GRL-085, and -097 potently inhibited the replication of HIV-1DRVRP51, with 13- and 6.8-fold differences (Table 2). Moreover, GRL-015, -085, and -097 showed potent antiviral activity against all seven recombinant multidrug-resistant clinical HIV-1 variants, exhibiting 0.7- to 10-fold differences, compared to DRV, which exhibited 62- to 117-fold differences (Table 3). Of note, GRL-085 mostly showed more potent antiviral activity against HIV-1DRVRP40, HIV-1DRVRP51, and the recombinant HIV-1 clones than GRL-012, which is identical to TMC310911 (31) (Tables 2 and 3), indicating that the novel PIs, especially GRL-085, should be further investigated as potential therapeutics for treating individuals harboring DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants.

X-ray crystal structure analyses suggest that GRL-015, -085, and -097 have strong binding interactions with HIV-1 protease (Fig. 2). The tetrahydropyran ring of the Tp-THF moiety showed a “chair” conformation in all four crystal structures, while the conformation of the THF ring remains the same as that seen for the bis-THF moiety of DRV (PDB ID 4HLA). Notably, the C-5 hydroxyl group substitution on the Tp-THF moiety gained an additional strong H bond with the carbonyl oxygen atom of G48 (located on the flap region of the protease) that should contribute to the enhanced antiviral activity of GRL-015, -085, and -097, especially against drug-resistant HIV-1 variants, compared to those of GRL-0476 and DRV (Tables 2 to 4). It has been reported that the HIV-1 protease (PR) flaps are highly flexible and can adopt a range of conformations (closed, semiopen, and open) (48–50), and the flap dynamics are altered by acquiring drug resistance-related amino acid substitutions in PR (51–53). Galiano et al. showed that the flaps of PR carrying multiple drug resistance-related mutations (at positions 10, 36, 46, 54, 62, 63, 71, 82, 84, and 90) adopt a more open conformation than those of wild-type PR, as assessed using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and distance measurements with pulsed electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy (54). The C-5 hydroxyl group has additional polar interactions with G48, located in the flap region of the protease, and this explains the improved antiviral potencies of GRL-015, -085, and -097 compared to those of GRL-0476 and DRV (Tables 2 to 4). In addition to the C-5 hydroxyl substitution, the P1 methoxybenzene moieties of GRL-085 and -097 provide improved interactions in the S2/S1 binding pockets of the protease compared to the P1 phenyl moieties of GRL-0476 and -015 (Fig. 3). In in vitro selection of resistant HIV-1 variants against GRL-085, the alanine at amino acid position 82 was changed to a valine in HIV11MIX085-WK50 and a phenylalanine in HIVDRVRP30085-WK50 (Fig. 6B and C), while none of the changes were seen in the selection against GRL-015 (Fig. 6B). The terminal methyl group of the P1 methoxybenzene moiety may alternate between the side chain of P81 and the backbone of G48, thus stabilizing the 80s loop (residues G78 to I85) (55) as well as the protease flap (residues I47 to I54). However, as shown in Fig. 3, the binding orientation of the terminal methyl group is pointed toward G48 (flap residue) rather than the 80s loop, suggesting that there may be improved nonbonded interaction between the methyl group of P1 methoxybenzene and the carbonyl oxygen atom of G48. Thus, the combination of the P-2 Tp-THF plus C-5 hydroxyl substitution and the P1 methoxybenzene moiety in GRL-085 and -097 may explain the increased antiviral activity of GRL-085 and -097 against drug-resistant HIV-1 variants and the higher genetic barrier to the development of resistance compared to the cases of GRL-0476 and -015.

Dimerization of PR subunits is an essential process for the acquisition of proteolytic activity of PR, which plays a critical role in viral maturation in the replication cycle of HIV-1 (56). Previously, we determined that DRV effectively blocks the dimerization of HIV-1 protease monomer subunits, as examined with the intermolecular FRET-based HIV expression assay. In addition, DRV binds to the active site of dimerized protease (19). More recently, we showed that DRV directly binds to the protease monomer subunit and inhibits PR dimerization (20). Thus, DRV's two protease inhibition modalities should explain the highly favorable clinical efficacy and high-level genetic barrier against HIV-1 acquisition of resistance to DRV in clinical settings (16, 17). In the present study, a high level of DRV-resistant viruses using wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 did not develop until 50 weeks in in vitro selection, while APV-resistant HIV-1 variants rapidly developed (Fig. 5A). In fact, DRV/RTV (DRV/r) monotherapy has been examined in HIV-1-infected patients (57–60), and the monotherapy regimen proved to be a potential long-term strategy to avoid nucleoside/nucleotide analogue toxicities and to reduce costs. Even though the protease dimerization inhibition activity of GRL-015, -085, and -097 was moderate compared to that of DRV (Fig. 4), no HIV-1 variants highly resistant to GRL-015, -085, or -097 were seen until 50 weeks using HIV-1NL4-3 (Fig. 5A). Most notably, GRL-085 and -097 did not allow the three HIV-1 populations (HIV-111MIX, HIV-1DRVRP30, and rCLHIV-1T48) to acquire significant resistance to either of the PIs throughout the 50 weeks' selection (Fig. 5B, C, and D). Amino acid sequence determination confirmed that no significant amino acid substitutions had occurred in HIV-111MIX, HIV-1DRVRP30, or rCLHIV-1T48.

In conclusion, the data obtained in the present study show that GRL-015, -085, and -097 exert potent activity against a wide spectrum of multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants, which may stem from the addition of the C-5-hydroxyl group to the Tp-THF moiety, delivering increased anti-HIV-1 potency compared to that of the structurally related, bis-THF-containing compound DRV. Furthermore, the P1 methoxybenzene moiety in GRL-085 and -097 should also be conducive to the observed high genetic barrier. The present data suggest that a component that strongly interacts with G48 of PR, such as the C-5-hydroxyl group of the Tp-THF moiety, may play a role in improving the anti-HIV-1 profile of PIs and may contribute to the design of more potent anti-HIV-1 compounds that are less likely to exhibit drug resistance.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; in part by grants for Promotion of AIDS Research from the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labor of Japan; in part by grants from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED); in part by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT); in part by grant from the National Center for Global Health & Medicine (NCGM) Research Institute (to H.M.); and in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM53386 to A.K.G.). This work was also supported in part by the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Platform for Drug Discovery, Informatics, and Structural Life Science) funded by MEXT and AMED.

This study utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (http://biowulf.nih.gov). We thank the synchrotron beam lines staff at Spring8 for their support in X-ray diffraction data collection.

Funding Statement

The HHS/National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labor of Japan, the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, the National Center for Global Health & Medicine (NCGM), and the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research supported by MEXT and AMED provided funding to Hiroaki Mitsuya. HHS/NIH provided funding to Arun K. Ghosh.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01829-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Edmonds A, Yotebieng M, Lusiama J, Matumona Y, Kitetele F, Napravnik S, Cole SR, Van Rie A, Behets F. 2011. The effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the survival of HIV-infected children in a resource-deprived setting: a cohort study. PLoS Med 8:e1001044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lohse N, Hansen AB, Gerstoft J, Obel N. 2007. Improved survival in HIV-infected persons: consequences and perspectives. J Antimicrob Chemother 60:461–463. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitsuya H, Maeda K, Das D, Ghosh AK. 2008. Development of protease inhibitors and the fight with drug-resistant HIV-1 variants. Adv Pharmacol 56:169–197. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(07)56006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, Mercincavage LM, Schackman BR, Sax PE, Weinstein MC, Freedberg KA. 2006. The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States. J Infect Dis 194:11–19. doi: 10.1086/505147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tejerina F, Bernaldo de Quiros JC. 2011. Protease inhibitors as preferred initial regimen for antiretroviral-naive HIV patients. AIDS Rev 13:227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, Duiculescu D, Eberhard A, Gutierrez F, Hocqueloux L, Maggiolo F, Sandkovsky U, Granier C, Pappa K, Wynne B, Min S, Nichols G, Investigators S. 2013. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 369:1807–1818. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. 2008. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet 372:293–299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakagawa F, May M, Phillips A. 2013. Life expectancy living with HIV: recent estimates and future implications. Curr Opin Infect Dis 26:17–25. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835ba6b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Hakim JG, Kumwenda J, Grinsztejn B, Pilotto JH, Godbole SV, Mehendale S, Chariyalertsak S, Santos BR, Mayer KH, Hoffman IF, Eshleman SH, Piwowar-Manning E, Wang L, Makhema J, Mills LA, de Bruyn G, Sanne I, Eron J, Gallant J, Havlir D, Swindells S, Ribaudo H, Elharrar V, Burns D, Taha TE, Nielsen-Saines K, Celentano D, Essex M, Fleming TR, HPTN 062 Study Team . 2011. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grigsby IF, Pham L, Mansky LM, Gopalakrishnan R, Mansky KC. 2010. Tenofovir-associated bone density loss. Ther Clin Risk Manag 6:41–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winston J, Chonchol M, Gallant J, Durr J, Canada RB, Liu H, Martin P, Patel K, Hindman J, Piontkowsky D. 2014. Discontinuation of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for presumed renal adverse events in treatment-naive HIV-1 patients: meta-analysis of randomized clinical studies. HIV Clin Trials 15:231–245. doi: 10.1310/hct1506-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Douce V, Janossy A, Hallay H, Ali S, Riclet R, Rohr O, Schwartz C. 2012. Achieving a cure for HIV infection: do we have reasons to be optimistic? J Antimicrob Chemother 67:1063–1074. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh AK, Kincaid JF, Cho W, Walters DE, Krishnan K, Hussain KA, Koo Y, Cho H, Rudall C, Holland L, Buthod J. 1998. Potent HIV protease inhibitors incorporating high-affinity P2-ligands and (R)-(hydroxyethylamino)sulfonamide isostere. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 8:687–690. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(98)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh AK, Krishnan K, Walters DE, Cho W, Cho H, Koo Y, Trevino J, Holland L, Buthod J. 1998. Structure based design: novel spirocyclic ethers as nonpeptidal P2-ligands for HIV protease inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 8:979–982. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(98)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh Y, Nakata H, Maeda K, Ogata H, Bilcer G, Devasamudram T, Kincaid JF, Boross P, Wang YF, Tie Y, Volarath P, Gaddis L, Harrison RW, Weber IT, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2003. Novel bis-tetrahydrofuranylurethane-containing nonpeptidic protease inhibitor (PI) UIC-94017 (TMC114) with potent activity against multi-PI-resistant human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:3123–3129. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3123-3129.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Meyer S, Vangeneugden T, van Baelen B, de Paepe E, van Marck H, Picchio G, Lefebvre E, de Bethune MP. 2008. Resistance profile of darunavir: combined 24-week results from the POWER trials. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 24:379–388. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dierynck I, De Wit M, Gustin E, Keuleers I, Vandersmissen J, Hallenberger S, Hertogs K. 2007. Binding kinetics of darunavir to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease explain the potent antiviral activity and high genetic barrier. J Virol 81:13845–13851. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01184-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh Y, Matsumi S, Das D, Amano M, Davis DA, Li J, Leschenko S, Baldridge A, Shioda T, Yarchoan R, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2007. Potent inhibition of HIV-1 replication by novel non-peptidyl small molecule inhibitors of protease dimerization. J Biol Chem 282:28709–28720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh Y, Aoki M, Danish ML, Aoki-Ogata H, Amano M, Das D, Shafer RW, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2011. Loss of protease dimerization inhibition activity of darunavir is associated with the acquisition of resistance to darunavir by HIV-1. J Virol 85:10079–10089. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05121-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi H, Takamune N, Nirasawa T, Aoki M, Morishita Y, Das D, Koh Y, Ghosh AK, Misumi S, Mitsuya H. 2014. Dimerization of HIV-1 protease occurs through two steps relating to the mechanism of protease dimerization inhibition by darunavir. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:12234–12239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400027111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koh Y, Amano M, Towata T, Danish M, Leshchenko-Yashchuk S, Das D, Nakayama M, Tojo Y, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2010. In vitro selection of highly darunavir-resistant and replication-competent HIV-1 variants by using a mixture of clinical HIV-1 isolates resistant to multiple conventional protease inhibitors. J Virol 84:11961–11969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00967-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitsuya Y, Liu TF, Rhee SY, Fessel WJ, Shafer RW. 2007. Prevalence of darunavir resistance-associated mutations: patterns of occurrence and association with past treatment. J Infect Dis 196:1177–1179. doi: 10.1086/521624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Marck H, Dierynck I, Kraus G, Hallenberger S, Pattery T, Muyldermans G, Geeraert L, Borozdina L, Bonesteel R, Aston C, Shaw E, Chen Q, Martinez C, Koka V, Lee J, Chi E, de Bethune MP, Hertogs K. 2009. The impact of individual human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease mutations on drug susceptibility is highly influenced by complex interactions with the background protease sequence. J Virol 83:9512–9520. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00291-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterrantino G, Zaccarelli M, Colao G, Baldanti F, Di Giambenedetto S, Carli T, Maggiolo F, Zazzi M. 2012. Genotypic resistance profiles associated with virological failure to darunavir-containing regimens: a cross-sectional analysis. Infection 40:311–318. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0237-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delaugerre C, Mathez D, Peytavin G, Berthe H, Long K, Galperine T, de Truchis P. 2007. Key amprenavir resistance mutations counteract dramatic efficacy of darunavir in highly experienced patients. AIDS 21:1210–1213. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32810fd744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Meyer S, Lathouwers E, Dierynck I, De Paepe E, Van Baelen B, Vangeneugden T, Spinosa-Guzman S, Lefebvre E, Picchio G, de Bethune MP. 2009. Characterization of virologic failure patients on darunavir/ritonavir in treatment-experienced patients. AIDS 23:1829–1840. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832cbcec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamiya S, Mardy S, Kavlick MF, Yoshimura K, Mistuya H. 2004. Amino acid insertions near Gag cleavage sites restore the otherwise compromised replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants resistant to protease inhibitors. J Virol 78:12030–12040. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.12030-12040.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshimura K, Kato R, Yusa K, Kavlick MF, Maroun V, Nguyen A, Mimoto T, Ueno T, Shintani M, Falloon J, Masur H, Hayashi H, Erickson J, Mitsuya H. 1999. JE-2147: a dipeptide protease inhibitor (PI) that potently inhibits multi-PI-resistant HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:8675–8680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harada S, Hazra R, Tamiya S, Zeichner SL, Mitsuya H. 2007. Emergence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants containing the Q151M complex in children receiving long-term antiretroviral chemotherapy. Antiviral Res 75:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aoki M, Danish ML, Aoki-Ogata H, Amano M, Ide K, Das D, Koh Y, Mitsuya H. 2012. Loss of the protease dimerization inhibition activity of tipranavir (TPV) and its association with the acquisition of resistance to TPV by HIV-1. J Virol 86:13384–13396. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07234-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dierynck I, Van Marck H, Van Ginderen M, Jonckers TH, Nalam MN, Schiffer CA, Raoof A, Kraus G, Picchio G. 2011. TMC310911, a novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor, shows in vitro an improved resistance profile and higher genetic barrier to resistance compared with current protease inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:5723–5731. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00748-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosh AK, Leshchenko S, Noetzel M. 2004. Stereoselective photochemical 1,3-dioxolane addition to 5-alkoxymethyl-2(5H)-furanone: synthesis of bis-tetrahydrofuranyl ligand for HIV protease inhibitor UIC-94017 (TMC-114). J Org Chem 69:7822–7829. doi: 10.1021/jo049156y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aoki M, Venzon DJ, Koh Y, Aoki-Ogata H, Miyakawa T, Yoshimura K, Maeda K, Mitsuya H. 2009. Non-cleavage site gag mutations in amprenavir-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) predispose HIV-1 to rapid acquisition of amprenavir resistance but delay development of resistance to other protease inhibitors. J Virol 83:3059–3068. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02539-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Louis JM, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. 1999. Autoprocessing of HIV-1 protease is tightly coupled to protein folding. Nat Struct Biol 6:868–875. doi: 10.1038/12327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yedidi RS, Garimella H, Aoki M, Aoki-Ogata H, Desai DV, Chang SB, Davis DA, Fyvie WS, Kaufman JD, Smith DW, Das D, Wingfield PT, Maeda K, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2014. A conserved hydrogen-bonding network of P2 bis-tetrahydrofuran-containing HIV-1 protease inhibitors (PIs) with a protease active-site amino acid backbone aids in their activity against PI-resistant HIV. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3679–3688. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00107-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yedidi RS, Maeda K, Fyvie WS, Steffey M, Davis DA, Palmer I, Aoki M, Kaufman JD, Stahl SJ, Garimella H, Das D, Wingfield PT, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2013. P2′ benzene carboxylic acid moiety is associated with decrease in cellular uptake: evaluation of novel nonpeptidic HIV-1 protease inhibitors containing P2 bis-tetrahydrofuran moiety. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:4920–4927. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00868-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. 1997. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr 30:1022–1025. doi: 10.1107/S0021889897006766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 1994. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS. 2011. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murshudov G, Vagin A, Dodson E. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamzin V, Wilson K. 1993. Automated refinement of protein models. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 49:129–147. doi: 10.1107/S0907444992008886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zwart PH, Langer GG, Lamzin VS. 2004. Modelling bound ligands in protein crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60:2230–2239. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904012995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moriarty NW, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD. 2009. electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): a tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 65:1074–1080. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909029436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang G, Weiser B, Visosky A, Moran T, Burger H. 1999. PCR-mediated recombination: a general method applied to construct chimeric infectious molecular clones of plasma-derived HIV-1 RNA. Nat Med 5:239–242. doi: 10.1038/5607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pieniazek D, Rayfield M, Hu DJ, Nkengasong JN, Soriano V, Heneine W, Zeh C, Agwale SM, Wambebe C, Odama L, Wiktor SZ. 2004. HIV-2 protease sequences of subtypes A and B harbor multiple mutations associated with protease inhibitor resistance in HIV-1. AIDS 18:495–502. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200402200-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hornak V, Okur A, Rizzo RC, Simmerling C. 2006. HIV-1 protease flaps spontaneously open and reclose in molecular dynamics simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:915–920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508452103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ishima R, Freedberg DI, Wang YX, Louis JM, Torchia DA. 1999. Flap opening and dimer-interface flexibility in the free and inhibitor-bound HIV protease, and their implications for function. Structure 7:1047–1055. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ishima R, Louis JM. 2008. A diverse view of protein dynamics from NMR studies of HIV-1 protease flaps. Proteins 70:1408–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Layten M, Hornak V, Simmerling C. 2006. The open structure of a multi-drug-resistant HIV-1 protease is stabilized by crystal packing contacts. J Am Chem Soc 128:13360–13361. doi: 10.1021/ja065133k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cai Y, Yilmaz NK, Myint W, Ishima R, Schiffer CA. 2012. Differential flap dynamics in wild-type and a drug resistant variant of HIV-1 protease revealed by molecular dynamics and NMR relaxation. J Chem Theory Comput 8:3452–3462. doi: 10.1021/ct300076y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Chang YC, Louis JM, Wang YF, Harrison RW, Weber IT. 2014. Structures of darunavir-resistant HIV-1 protease mutant reveal atypical binding of darunavir to wide open flaps. ACS Chem Biol 9:1351–1358. doi: 10.1021/cb4008875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galiano L, Ding F, Veloro AM, Blackburn ME, Simmerling C, Fanucci GE. 2009. Drug pressure selected mutations in HIV-1 protease alter flap conformations. J Am Chem Soc 131:430–431. doi: 10.1021/ja807531v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stebbins J, Towler EM, Tennant MG, Deckman IC, Debouck C. 1997. The 80's loop (residues 78 to 85) is important for the differential activity of retroviral proteases. J Mol Biol 267:467–475. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wlodawer A, Miller M, Jaskolski M, Sathyanarayana BK, Baldwin E, Weber IT, Selk LM, Clawson L, Schneider J, Kent SB. 1989. Conserved folding in retroviral proteases: crystal structure of a synthetic HIV-1 protease. Science 245:616–621. doi: 10.1126/science.2548279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]