Abstract

PURPOSE:

The purpose of this study is to determine whether singleport laparoscopic repair (SLR) for incarcerated inguinal hernia in children is superior toconventional repair (CR) approaches.

METHOD:

Between March 2013 and September 2013, 126 infants and children treatedwere retrospectively reviewed. All the patients were divided into three groups. Group A (48 patients) underwent trans-umbilical SLR, group B (36 patients) was subjected to trans-umbilical conventional two-port laparoscopic repair (TLR) while the conventional open surgery repair (COR) was performed in group C (42 patients). Data regarding the operating time, bleeding volume, post-operative hydrocele formation, testicular atrophy, cosmetic results, recurrence rate, and duration of hospital stay of the patients were collected.

RESULT:

All the cases were completed successfully without conversion. The mean operative time for group A was 15 ± 3.9 min and 24 ± 7.2 min for unilateral hernia and bilateral hernia respectively, whereas for group B, it was 13 ± 6.7 min and 23 ± 9.2 min. The mean duration of surgery in group C was 35 ± 5.2 min for unilateral hernia. The recurrence rate was 0% in all the three groups. There were statistically significant differences in theoperating time, bleeding volume, post-operative hydrocele formation, cosmetic results and duration hospital stay between the three groups (P < 0.001). No statistically significant differences between SLR and TLR were observed except the more cosmetic result in SLR.

CONCLUSION:

SLR is safe and effective, minimally invasive, and is a new technology worth promoting.

Keywords: Children, incarcerated inguinal hernia, single-port laparoscopy, surgical repair

INTRODUCTION

Inguinal hernia is a common disease in children. Treatment of this disease by laparoscopic high ligation of the hernia sac has been accepted by domestic and foreign scholars.[1,2] Incarcerated hernia is the most common and serious complication, the incidence of incarcerated inguinal hernia cases is 1/6th of the total population with inguinal hernia. In the conventional approach, incarcerated inguinal hernias are manually reduced and the surgical repair is delayed by 1 day or 2 days when one has to wait for the oedema to lessen,[3] thus reducing the surgical risk in a traumatized anatomy. This report describes immediate laparoscopy when manual reduction fails and, after intra-operative combined laparoscopic plus external manual reduction, immediate laparoscopic treatment of the hernia. Now single-incision surgery is becoming increasingly popular among adult patients,[4] particularly cholecystectomy[5] and urologic indications,[6,7] and our institute has reported single-incision laparoscopic Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy using conventional instruments for children with choledochal cysts in 2012.[8] Compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery, the single-incision approach is initially cumbersome and entails some unique and novel challenges. So, in this study we introduced a novel surgical approach [single-port laparoscopic repair (SLR)] for incarcerated inguinal hernia and evaluated the safety and efficacy of it.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Between March 2013 and September 2013, patients in our centre who were operated by the same surgeon were retrospectively reviewed. Based on the time of admission, all the patients were divided into three groups (the first, second and third 10-day period of a month corresponds to group A, B and C respectively). Group A (aged 2 months to 4 years; median age: 1.9 years; gender distribution: 27 boys and 21 girls) presented with incarcerated hernia (16 left-sided and 32 right-sided). Group B (aged 1 month to 4 years; median age: 1.8 years; gender distribution: 21 boys and 15 girls) presented with incarcerated hernia (17 left-sided and 19 right-sided). Group C (aged 1 month to 3.5 years; median age: 2 years; gender distribution: 20 boys and 22 girls) presented with incarcerated hernia (20 left-sided and 22 right-sided). In all the 126 cases, external reduction was unsuccessful or incomplete. These children were taken to the operating room as an emergency. There were no statistically significant differences among the three groups in the general clinical data. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Capital Institute of Paediatrics. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the incarcerated inguinal hernia patients before the surgery.

Diagnosis and follow-up

Clinical manifestations were sudden crying and anxiety with visible mass in the groin, scrotum or labia major. On physical examination, local irreducible mass with high tension and obvious tenderness was observed. B-scan ultrasonography could diagnose incarcerated inguinal hernia and confirmed the contents of hernia. The main outcome of the measurements was operative time, duration of hospital stay, post-operative hydrocele formation, recurrence rate, testicular atrophy and cosmetic results. All the patients were followed up in the outpatient clinic after 7 days, 2 weeks, 3 months and 6 months. The patients’ follow-up time was 3 months to 9 months.

SLR technique

An incision was made down to the fascia and CO2 was insufflated to a pressure of 12 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kappa). The verse needle was exchanged with a 1-cm trocar (Changzhou Haida) and the pressure was lowered to 10 mmHg. A Z-laparoscope (Hangzhou Tonglu General Factory of Medical Optical Instruments) was inserted at the umbilicus with a no-damage clamp [Figure 1]. A diagnostic laparoscopy was done that included an inspection of the internal genitalia, the bowels and the parenchymatous organs [Figure 2]. With the help of pneumoperitoneal pressure and no-damage clamp, the incarcerated inguinal hernia can be pulled; the injury of the incarcerated organs can then be observed. If there was no injury, first, the open internal ring that had prompted the diagnosis was closed with a suture [Figure 3]. If, unexpectedly, a contralateral open internal ring was found of the same calibre or slightly smaller, it also was closed at this stage. Openings smaller than the diameter of the needle holder were designated ‘open processes vaginitis’ and were left open. Regular sutures for open surgery were used (2-0 non- absorbable sutures, Johnson, USA). Needle holders of size 5 mm were used for stitching and extra-corporeal knotting. These sutures were directly passed into the abdomen through the abdominal wall. One end was in the abdomen while the other end was outside it. The tissue grasped for stitching principally was serosa but included some underlying muscular tissue as well. The stitches were placed in such a manner that the gonadal vessels and the vas deferens were left unimpaired within a relatively loose fold. When the first knot was completed, both ends of the suture were tightened for the second. The post-operative recovery picture could be seen in Figure 4.

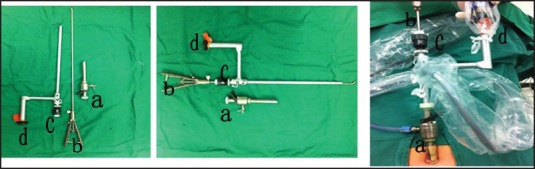

Figure 1.

(a) Trocar (b) No-damage clamp (c) Operation port (d) Laparoscopic lens

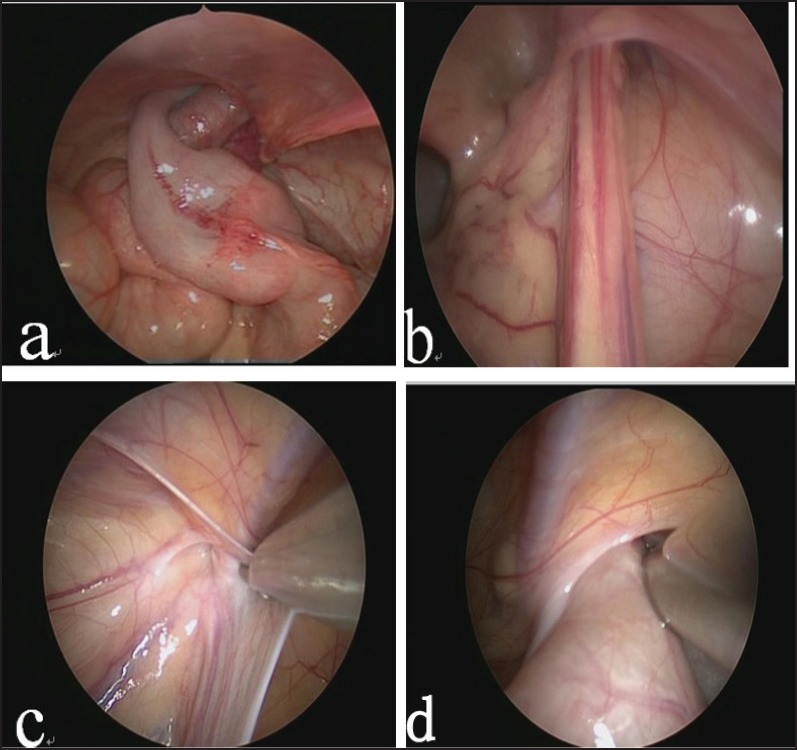

Figure 2.

(a) Intra-operative photograph showing a 3-year-old boy with incarcerated bowel (b) The incarcerated content is the momentum of 2-year-old girl (c) Intra-operative photograph to detect recessive contralateral hernia (d) The hernia contents pulled out

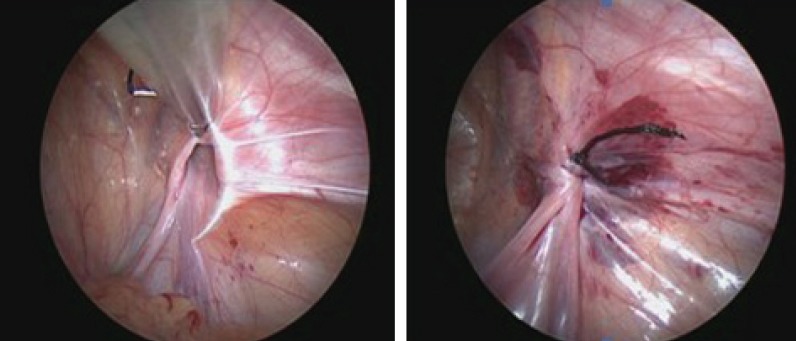

Figure 3.

The high ligation of hernia sac was given

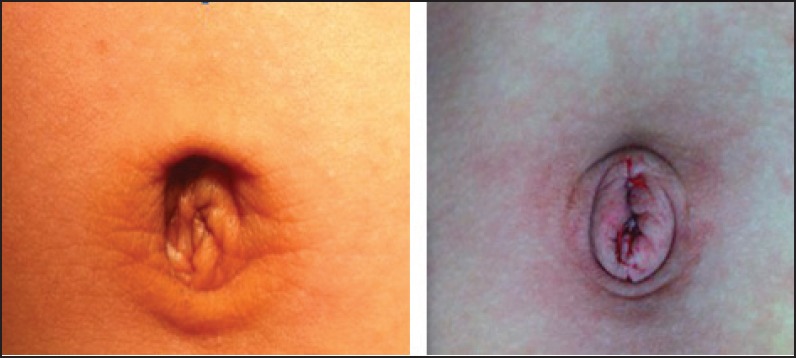

Figure 4.

Left: Pre-operative picture; Right: Post-operative picture

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 19 (Sweet, Stephen A., Addison-Wesley). Descriptive statistical analysis included the calculation of means, medians and standard deviation (SD) of the data obtained. The continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using a two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test; the categorical variables were compared using χ2 or Fisher's method. P < 0.05 was considered significant in all the analyses.

RESULTS

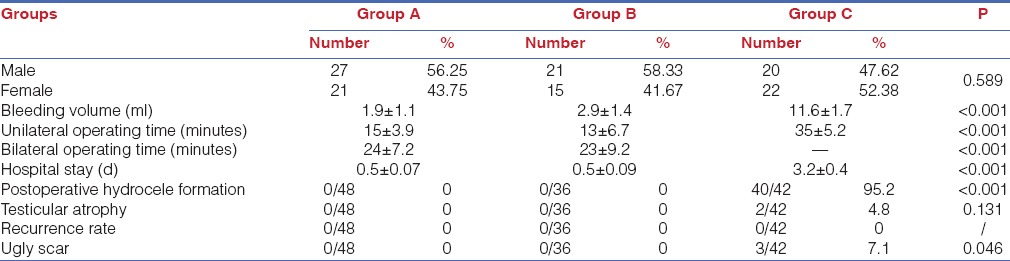

Surgery on three groups of children was successfully completed. No intra-operative complications occurred during this study. The results are shown in Table 1. The contralateral internal ring was open unexpectedly in 20.9% of the patients (10/48) in group A and 19.6% of the patients (9/46) in group B. Children of groups A and B who were awake after anaesthesia, were offered regular diet 4 h after the surgery, and were discharged on the same day (mean post-operative duration being 12 h), with the exception of those who were required to stay 1 night for monitoring. In the study period, all the infants could endure post-operative pain without wound infection and neither recurrence nor post-operative complications was observed. Group C children could eat when they were awake after anaesthesia but post-operative analgesia was needed. Forty children were diagnosed to have inguinal or scrotal oedema. The patients were discharged with the mean period being 3 days after the operation. The follow-up time was 3 months to 9 months. There were no recurrences in all three groups but eight patients in group C were re-admitted due to contralateral side inguinal hernia.

Table 1.

Comparison of three groups of children (x ± s)

DISCUSSION

Incarcerated inguinal hernia is a common disease in children's emergency surgery. If not treated timely and appropriately, serious complications, such as intestinal obstruction, intestinal strangulation, intestinal perforation or ovarian necrosis, are possible. If children are generally in a good condition or the incarceration time is less than 12 h, manual reduction could be tried. This manoeuvre is not without risk because it refrains from direct visual control. The mechanical damage, caused internally, is never seen, not even during subsequent surgery. Therefore, incorrect or incomplete reduction is not uncommon.[9] Subsequent surgical correction is performed after 1 day or 2 days and carries an increased risk because it is executed in traumatized anatomy. The total procedure may keep the child in hospital for 3 days.

The conventional approach to incarceration is open surgery but it undermines the physiological anatomy of the inguinal canal. Due to inflammatory oedema, the vas deferens and the testicular vessels may be intra-operatively injured, and scrotal hematoma and oedema is post-operatively possible. With the development of laparoscopic techniques, multi-centres have successfully undertaken incarcerated inguinal hernia surgery with laparoscopic repair.[10,11,12] Pneumoperitoneum may help to widen the internal ring[13] and further facilitates the reduction of incarcerated hernia during laparoscopy. Advantages of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair include excellent visual exposure, the ability to evaluate the contralateral side, minimal dissection and avoidance of access trauma to the vas deferens and the testicular vessels, iatrogenic ascent of the testis, and decreased operative time, especially in recurrent and obese cases.[14]

Single-incision surgery is becoming increasingly popular among adult patients,[4] particularly cholecystectomy[5] and urologic indications,[6,7] and our institute has reported single-incision laparoscopic Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy using conventional instruments for children with choledochal cysts in 2012. Compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery, the single-incision approach is initially cumbersome because there are several challenges to overcome such as:

Trocar crowding,

Fewer degrees of freedom,

Clashing instruments, and

Limited number of working ports. So, we introduce the novel method, i.e., SLR that has not been previously reported for incarcerated inguinal hernia.

Our centre actively gave surgical treatment to children who were contraindicated to manual reduction and manual reduction not reset. All the patients were divided into three groups. Group A (48 patients) underwent SLR, group B (36 patients) underwent TLR while conventional open surgery repair (COR) was performed in group C (42 patients). We compared the three groups’ surgical efficacy and found that there were statistically significant differences in the operating time (P < 0.001), bleeding volume (P < 0.001), post-operative hydrocele formation (P < 0.001), cosmetic results (P = 0.046) and duration of hospital stay (P < 0.001); among the three groups, the minimally invasive group was significantly better than the open group. No statistically significant differences were observed between group A and group B, except the more cosmetic result in group A that was more easily accepted by the children and their parents. The most striking advantage of SLR is the virtually scar-less appearance after operation. Through the research, SLR for incarcerated inguinal hernia appears to be more safe and cost-effective. At the same time, we believe that there must be a wealth of experience in porous laparoscopic techniques before using this technique.

To summarise, this study shows that SLR for incarcerated inguinal hernia not only maintains the advantages of the porous laparoscopic surgery but can also further reduce surgical trauma. Single-port surgery provides a potentially more broadly applicable and accessible technique to the surgeon with a pre-existing minimally invasive skill, and therefore, is gaining momentum as a means of offering virtually ‘scar-less’ surgery. This technicality truly achieves virtually scar-less appearance, is safe and effective, minimally invasive and is a new technology worth promoting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank those authors who provided us with the full text and those patients who support our work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: There was no funding source for this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gholoum S, Baird R, Laberge JM, Puligandla PS. Incarceration rates in pediatric inguinal hernia: Do not trust the coding. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1007–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, Li JW, Zhang Y, Sun J, Zheng MH, Dong F. The surgical strategy for laparoscopic approach in recurrent inguinal hernia repair: 213 cases report. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2013;51:792–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapur P, Caty MG, Glick PL. Pediatric hernias and hydroceles. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45:773–89. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamberlain RS, Sakpal SV. A comprehensive review of single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) techniques for cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1733–40. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0902-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow A, Purkayastha S, Paraskeva P. Appendicectomy and cholecystectomy using single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS): The first UK experience. Surg Innov. 2009;16:211–7. doi: 10.1177/1553350609344413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canes D, Berger A, Aron M, Brandina R, Goldfarb DA, Shoskes D, et al. Laparo-endoscopic single site (LESS) versus standard laparoscopic left donor nephrectomy: Matched-pair comparison. Eur Urol. 2010;57:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rassweiler J. Editorial comment on: Single-incision, umbilical laparoscopic versus conventional laparoscopic nephrectomy: A comparison of perioperative outcomes and short-term measures of convalescence. Eur Urol. 2009;55:1205. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diao M, Li L, Dong N, Li Q, Cheng W. Single-incision laparoscopic Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy using conventional instruments for children with choledochal cysts. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1784–90. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stylianos S, Jacir NN, Harris BH. Incarceration of inguinal hernia in infants prior to elective repair. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:582–3. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(93)90665-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Celebi S, Uysal AI, Inal FY, Yildiz A. A single-blinded, randomized comparison of laparoscopic versus open bilateral hernia repair in boys. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014;24:117–21. doi: 10.1089/lap.2013.0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaya M, Hückstedt T, Schier F. Laparoscopic approach to incarcerated inguinal hernia in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:567–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tam YH, Lee KH, Sihoe JD, Chan KW, Cheung ST, Pang KK. Initial experience in children using conventional laparoscopic instruments in single-incision laparoscopic surgery. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:2381–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreno-Egea A, Girela E, Parlorio E, Aguayo-Albasini JL. Controversies in the current management of traumatic abdominal wall hernias. Cir Esp. 2007;82:260–7. doi: 10.1016/s0009-739x(07)71723-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saranga Bharathi R, Arora M, Baskaran V. Pediatric inguinal hernia: Laparoscopic versus open surgery. JSLS. 2008;12:277–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]