Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

The aim of this study was to evaluate patients with end stage renal failure (ESRD) who underwent chronic peritoneal dialysis (CPD). The clinical outcomes of laparoscopic and open placements of catheters were compared.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

We reviewed 49 (18 male and 31 female) children with CPD according to age, sex, cause of ESRD, catheter insertion method, kt/V rate, complications, presence of peritonitis, catheter survival rate between January 2002 and February 2014.

RESULTS:

Thirty-three patients were with open placement and 16 patients were with laparoscopic placement. The rate of the peritonitis is significantly less in patients with laparoscopic access than open access (n = 4 vs n = 25) (P <0.01). Patients with peritonitis were younger than those who had no attack of peritonitis (10.95 ± 0.8 years vs 13.4 ± 0.85 years). According to the development of complications, significant difference has not been found between the open (n = 9) and laparoscopic (n = 3) approaches except the peritonitis. Catheter survival rate for the first year was 95%, and for five years was 87.5%. There was no difference between open and laparoscopic group according to catheter survival rate. The mean kt/V which indicates the effectiveness of peritoneal dialysis was mean 2.26 ± 0.08. No difference was found between laparoscopic and open methods according to kt/V.

CONCLUSION:

Laparoscopic placement of CPD results in lower peritonitis rate. Catheter survival rate was excellent in both groups. Single port laparoscopic access for CPD catheter insertion is an effective and safe method.

Keywords: Chronic Peritoneal diaysis, complication, open placement, peritonitis, single-port laparoscopic placement

INTRODUCTION

Chronic peritoneal dialysis (CPD) is an effective treatment modality in the management of children with end-stage renal failure (ERDS).[1,2] There are three main techniques for peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheter insertion; open surgical technique, percutanous Seldinger technique, and laparoscopic technique.[3,4,5] The best technique for inserting PD catheter is still controversial.[6] Recently, laparoscopic technique has become more popular owing to the shorter hospital stay and more accurate placement of the catheter.[7,8] Peritonitis and catheter-related infections are still common complications and they are major causes of morbidity.[9] Peritonitis, pericatheter leakage, exit site infection, failure of fluid drainage due to mechanical dysfunction, and incorrect positioning are the main complications.[10]

We have developed a single port modified technique of laparoscopic placement of peritoneal dialysis catheter. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical outcomes of this modified laparoscopic technique and open placements of peritoneal catheters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

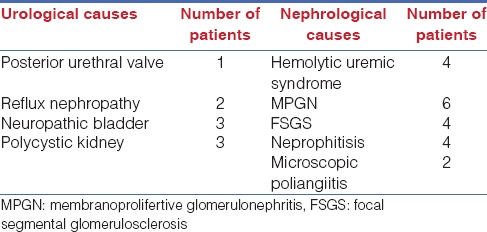

Medical records of 49 patients (18 male, 31 female) on PD were reviewed between January 2002 and February 2014. The median age of patients was 15 (range: 3-18 year) in females and 12 (range: 6-17 year) in males. Age, sex, cause of ESRD, catheter insertion method, kt/V rate, peritonitis or other complications, and catheter survival rate were reviewed. The etiology of ESRD was urologic origin in nine patients, nephrologic origin in 20 and etiology could not be determined in 20 patients [Table 1].

Table 1.

Etiologies of end stage renal disease (ESRD).

Kt/V (K; dialyzer clearance of urea, t; dialysis time, V; volume of distribution of urea in the body) is a parameter which is used to quantify the dialysis treatment adequacy.

All surgical procedures were performed under general anesthesia and all patients received a double-cuff curled PD catheter (Kendall, Tyco® peritoneal catheter, Hampshire, UK).

Surgical techniques

Open surgical method; A midline vertical incision was made under the umbilicus and the catheter was inserted into Douglas pouch. Intramuscular tunnel was created up to supra-umbilical area in a semilunar shape. The catheter was passed through the tunnel and exit to the skin. Only the patients, whose omentum is large and mobile enough to come to the incision, underwent omentectomy.

Laparoscopic method

After diagnostic laparoscopy, the site of the catheter on the right abdominal wall was marked according to the supposed places of the cuffs of the catheter, keeping some distance to the umbilicus. An incision was made on the cranial mark. Afterwards, a subcutaneous tunnel directing caudally was created. The guidebar of the catheter-set was placed through the tunnel into the abdominal cavity. The entrance point of the guidebar into the abdominal cavity at the peritoneum represented the place of caudal cuff of the catheter. Thereafter, a dissector and the catheter itself were placed through the same tunnel. The catheter was placed to the Douglas pouch. An optic forceps made for bronchoscopy replaced the conventional laparoscopy telescope and was inserted through the umbilical port. The catheter was placed its final position. In all cases, the omentum was grasped by the optic forceps. The umbilical trocar is removed, while optic forceps grasping the omentum was kept in situ. The optic forceps with omentum were taken out through the trocar-site and the omentum was excised ex-corpo.

Peritonitis was defined as clinical features (abdominal pain, fever, and cloudy dialysate) and leukocytosis in dialysis solution (white blood cell count >1000 µl with >50% neutrophils).[11]

In the case of peritonitis, the initial management is always conservative. Withdrawal of catheter is only indicated in patients with failed conservative treatment of systemic antibiotics or recurrent peritonitis attacks.

The application of dialysis before 2 weeks subsequent to catheter placement was defined as “early usage” and after 2 weeks as “late usage.”

Statistical analysis

Descriptic statistics were performed. For comparison of groups, ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis variance analysis, Chi-square test or Fishers’ exact test, and Mann-Whitney U test were used after normality analysis.

RESULTS

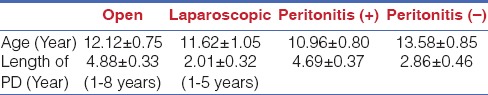

Thirty-three of the catheters were placed by open method (21 female and 12 male) whereas 16 were placed by laparoscopy (10 female and 6 male). The mean age of the patients was 11.95 ± 0.61 (12.12 ± 0.75 in open group; 11.62 ± 1.05 in the laparoscopic group). There was no difference between open and laparoscopic methods, as well as between males and females.

Total of 29 patients had peritonitis (59.1%) (16 females and 13 males) and only four of them developed after laparoscopic placement (25% in laparoscopic 75% in open group). The frequency of the peritonitis was significantly less in patients with laparoscopic access when compared to those with open method (P = 0.001). Patients with peritonitis were younger (10.95 ± 0.8) than those without peritonitis (13.4±0.85) (P = 0.049) [Table 2]. There was no significant difference in frequency of peritonitis between patients with underlying urologic or nephrological problems (P = 0.167) [Table 3]. Initially, all patients with peritonitis were treated conservatively, but in nine patients with peritonitis, the conservative management failed and we had to remove these patients’ catheters.

Table 2.

Mean age and length of PD measurement according to PD technique, presence of peritonitis

Table 3.

Number of peritonitis and other complications according to PD technique and etiology of ESRD

In nine patients, the catheter was used early after placement. Three of them had peritonitis. Dialysate leakage was not observed in patients with early usage. Forty patients were in the “late use” group and 23 of them developed peritonitis. There was no significant difference between early and late usage of PD according to development of peritonitis (P = 0.455).

Other complications were in total of 12 patients (24.5 %) including catheter leakage (n = 5), catheter obstruction leading to inadequate inflow and outflow (n = 4), exit-site or tunnel infection (n = 3). No significant difference was found between the open (nine complications) and laparoscopic (three complications) groups in terms of complication development (P = 0.541). Complication frequency was not different between patients with urological and nephrological problems either (P = 0.406) [Table 3]. In the laparoscopic group, two patients had catheter obstruction and one patient had a leakage. Patients with leakage were treated conservatively (Decreasing filling volume, switch to automated peritoneal dialysis temporarily). From the patients with catheter obstruction, three catheters were revised and the remaining one recovered without surgical intervention. One patient had catheter migration; his catheter was removed. Patients with exit-site or tunnel infection were treated conservatively.

Five patients were converted to hemodialysis due to recurrent peritonitis. None of them belonged to the laparoscopic group. Renal transplantation was performed in 12 patients. Inguinal hernia was developed in four male patients subsequently and one of them was bilateral.

Catheter survival rate for the first and second years was 95% in both groups and catheter survival rate for the 5 years were 87.5% in the open group. Since inadequate number of patients in the laparoscopic group had surveyed longer than 5 years, we are not able to measure catheter survival rate for 5 years in those patients.

The mean kt/V which indicates the effectiveness of peritoneal dialysis was 2.26 ± 0.08 in all patients. kt/V values were not different between laparoscopic and open approach groups (2.20 ± 0.17 vs 2.28 ± 0.1) (P = 0.416).

Three patients died due to septic complications and peritonitis. All of them were in the open group. There was no significant difference of survival between open and laparoscopic groups.

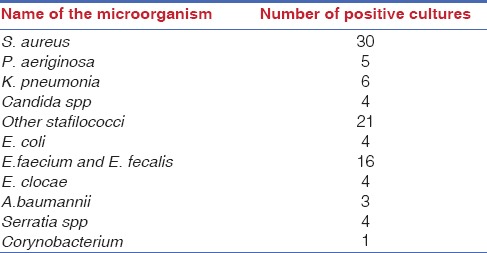

Microbiologic analysis of the blood and/or peritoneal fluid of those with peritonitis is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Number of positive cultures in patients with peritonitis

DISCUSSION

PD is an effective and alternative method for renal replacement therapy in children with ESRD to enhance patient's survival and quality of life. The major advantage of the PD is its easy use as home setting by caregivers.[12,13] There are three main methods available for PD placement including open, laparoscopic approaches, and Seldinger method. In all types of placements, complications may occur such as catheter obstruction and leakage, tunnel infection, or peritonitis. These complications may decline the quality of life of the patients and duration of catheter.[14,15,16]

Laparoscopic catheter placement for PD provides direct vision, minimal invasion, and accurate positioning of catheter into pelvis[17,18,19] as well as a more proper omentectomy. Many investigators suggested that laparoscopic catheter placement is superior to open method in terms of the complication rate (especially peritonitis) and catheter survival.[8,20] In this study, we did not detect such advantages except peritonitis which was very low in laparoscopic group (25 in open group vs 4 in laparoscopic group). The cause of dialysis associated peritonitis in children is not clear. Contamination, training, prophylactic antibiotics, patient age were primary factors that affect the incidence of peritonitis. The incidence of peritonitis was less in laparoscopic catheter insertion group. Accurate placement with direct vision provides more appropriate positioning of the catheter. Omentectomy was performed in all of our patients with laparoscopic access by direct vision. Laparoscopic insertion favors in terms of omentectomy because of better vision of omentum. We think omentectomy decreases complication rate particularly related to obstruction and peritonitis,[15,21] though survival rates were similar in both groups in the current study. The reason might be shorter duration of follow up for patients with laparoscopic catheter placement.

Many studies suggested that laparoscopic catheter placement has no obvious advantages over open placement according to complication rate, cost-effectiveness, and length of procedure.[17,22,23] However, we suggest laparoscopic placement has lower peritonitis rate and less incidence of catheter migration due to the ability of direct vision of peritoneal cavity. Similarly, some authors[24,25] claim that placement modality catheter survival had no superiority on catheter survival, but some others[2,26] suggest that laparoscopic placement had higher catheter survival.

Many technical modifications have been described for the laparoscopic placement.[27] Our modified method provides an easier placement. The usage of optic forceps for the laparoscopic insertion of peritoneal dialysis catheter facilitates the dissection. It reduces the need for additional trocar and provides appropriate position of the catheter. The omentectomy is much simpler than other laparoscopic placement methods.

In conclusion, catheter survival rate was excellent both in open and single port laparoscopic surgery groups. None of the method is complication free and rates of complications are similar in both groups except the peritonitis which is significantly lower in the laparoscopic group. The single port laparoscopic method for the CPD seems to be safe, effective, and cosmetically superior. Laparoscopic method for CPD may lead to less peritonitis episodes.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Milliken I, Fitzpatrick M, Subramaniam R. Single-port laparoscopic insertion of peritoneal dialysis catheters in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2006;2:308–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogunc G, Tuncer M, Ogunc M, Yardimsever M, Ersoy F. Laparoscopic omental fixation technique vs open surgical placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1749–55. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8586-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stringel G, Mcbride W, Weiss R. Laparoscopic placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:857–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harissis HV, Katsios CS, Koliousi EL, Ikonomou MG, Siamopoulos KC, Fatouros M, et al. A new simplified one port laparoscopic technique of peritoneal dialysis catheter placement with intra-abdominal fixation. Am J Surg. 2006;192:125–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atapour A, Asadabadi HR, Karimi S, Eslami A, Beigi AA. Comparing the outcomes of open surgical techniques and percutaneously peritoneal dialysis catheter (CPD) insertion using laparoscopic needle: A two month follow-up study. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:463–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aksu N, Yavascan O, Anil M, Kara OD, Erdogan H, Bal A. A ten year single-centre experience in children on chronic peritoneal dialysis-significance of percutaneous placement of peritoneal dialysis catheter. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2045–51. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu CT, Watson DI, Ellias TJ, Faull RJ, Clarkson AR, Bannister KM. Laparoscopic placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters: 7 years experience. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:109–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt SC, Pohle C, Langrehr JM, Schumacher G, Jacob D, Neuhaus P. Laparoscopic-assisted placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters: Implantation technique and results. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:596–9. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahim KA, Seidel K, McDonald RA. Risk factors for catheter related complications in pediatric peritoneal dialysis. Pediatr Neprhol. 2004;19:1021–8. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh TJ, Wei CF, Chin TW. Catheter related complications of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Eur J Surg. 1992;158:277–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke M, Hawley CM, Badve SV, McDonald SP, Brown FG, Boudville N, et al. Relapsing and recurrent peritoneal dialysis — Associated peritonitis: A multicentre registry study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:429–36. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grünberg J, Verocay MC, Rebori A, Pouso J. Comparison ofchronic peritoneal dialysis outcomes in children with and without spina bifida. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:573–7. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0369-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prasad N, Gulati S, Gupta A, Sharma RK, Kumar A, Kumar R, et al. Continuous peritoneal dialysis in children: A single-center experience in a developing country. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:403–7. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-2090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chadha V, Schaefer FS, Warady BA. Dailysis-associated peritonitis in children. Pediatr Neprhol. 2010;25:425–40. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-1113-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cribbs RK, Greenbaum LA, Heiss KF. Risk factors for early peritoneal dialysis catheter failure in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:585–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leblanc M, Quimet D, Pichette V. Dialysate leaks in peritoneal dialysis. Semin Dial. 2001;14:50–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2001.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jwo SC, Chen KS, Lee CC, Chen HY. Prospective randomized study for comparison of open surgery with laparoscopic-assisted placement of Tenckhoff peritoneal dialysis catheter — A single center experience and literature review. J Surg Res. 2010;159:489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manaouras AJ, Kekis PB, Stamou KM, Konstadoulakis MM, Apostolidis NS. Laparoscopic placement of Oreopoulos-Zellerman catheters in CAPD patients. Perit Dial Int. 2004;24:252–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jwo SC, Chen KS, Lin YY. Video-assisted laparoscopic procedures in peritoneal dialysis. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1666–70. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emir H. Endoscopic surgery for peritoneal dialysis catheters in children. In: Bax KM, Georgeson KE, Rothenberg SS, editors. Endoscopic surgery in infants and children. 1st ed. Chapter 66. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2008. pp. 485–98. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ladd AP, Breckler FD, Novotny NM. Impact of primary omentectomy on longevity of peritoneal dialysis catheters in children. Am J Surg. 2011;201:401–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsimoyiannis EC, Siakas P, Glantzounis G, Toli C, Sferopoulos G, Pappas M, et al. Laparoscopic placement of the tenckhoff catheter for peritoneal dialysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2000;10:218–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medani S, Shantier M, Hussein W, Wall C, Mellotte G. A comparative analysis of percutaneous and open surgical techniques for peritoneal catheter placement. Perit Dial Int. 2012;32:628–35. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2011.00187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright MJ, Bel’eed K, Johnson BF, Eadington DW, Sellars L, Farr MJ. Randomized prospective comparison of laparoscopic and open peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion. Perit Dial Int. 1999;19:372–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park YS, Min SI, Kim DK, Oh KH, Min SK, Kim SM, et al. The outcomes of percutaneous versus open placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters. World J Surg. 2014;38:1058–64. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2346-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gadallah MF, Pervez A, el-Shahawy MA, Sorrells D, Zibari G, McDonald J, et al. Peritoneoscopic versus surgical placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters: A prospective randomized study on outcome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:118–22. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh CN, Liao CH, Liu YY, Cheng CT, Wang SY, Chiang KC, et al. Dual-incision laparoscopic surgery for peritoneal dialysis catheter implantation and fixation: A novel, simple, and safe procedure. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:673–8. doi: 10.1089/lap.2013.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]