Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Laparoscopy is a well-established alternative to open surgery for treating many diseases. Although laparoscopy has many advantages, it is also associated with disadvantages, such as slow learning curves and prolonged operation time. Fresh frozen cadavers may be an interesting resource for laparoscopic training, and many institutions have access to cadavers. One of the main obstacles for the use of cadavers as a training model is the difficulty in introducing a sufficient pneumoperitoneum to distend the abdominal wall and provide a proper working space. The purpose of this study was to describe a fresh human cadaver model for laparoscopic training without requiring a pneumoperitoneum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS AND RESULTS:

A fake abdominal wall device was developed to allow for laparoscopic training without requiring a pneumoperitoneum in cadavers. The device consists of a table-mounted retractor, two rail clamps, two independent frame arms, two adjustable handle and rotating features, and two frames of the abdominal wall. A handycam is fixed over a frame arm, positioned and connected through a USB connection to a television and dissector; scissors and other laparoscopic materials are positioned inside trocars. The laparoscopic procedure is thus simulated.

CONCLUSION:

Cadavers offer a very promising and useful model for laparoscopic training. We developed a fake abdominal wall device that solves the limitation of space when performing surgery on cadavers and removes the need to acquire more costly laparoscopic equipment. This model is easily accessible at institutions in developing countries, making it one of the most promising tools for teaching laparoscopy.

Keywords: Cadaver, laparoscopy, teaching

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopy is a well-established alternative to open surgery for treating many diseases.[1] Compared to open surgery, the laparoscopic approach is associated with more acceptable and aesthetically pleasing surgical scars, less post-operative pain, shorter hospital stays and faster recovery after surgery.[1,2,3] Although laparoscopy has many advantages, it is also associated with disadvantages, such as slow learning curves and prolonged operation time.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] These skills are not inborn, and open surgery skills are not transferable to laparoscopic surgery.[11,12]

The difficulty with mastering laparoscopic surgery is related to features that are not found in open surgery. Minimally invasive surgery involves images in two dimensions (2D), limited feedback of movements and diminished sensibility.[13] Therefore, it is necessary to develop proper hand-eye coordination, dexterity with laparoscopic forceps, a sense of depth in 2D and the ability to adjust to the fulcrum effect, which creates a conflict between visual and proprioceptive feedback.[7,14,15] Considering these challenges, societies and regulatory bodies such as the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) and the European Association of Endoscopic Surgeons (EAES) have stipulated minimum prerequisites for surgeons who are performing laparoscopic surgery.[16,17,18,19] This has resulted in the development of skill-training laboratories and simulation models, allowing surgeons to develop laparoscopic skills without putting patients at risk.[20,21]

Currently, there are different simulation models for laparoscopic training. They facilitate the acquisition of laparoscopic skills, which can then be transferred to actual laparoscopic surgery.[7,12,14,22,23] Fresh frozen cadavers may be an interesting resource for laparoscopic training, and many institutions have access to cadavers.[24,25,26,27] This approach allows for the training of basic and advanced skills, using a simulation that more closely matches reality by providing access to real anatomy. One of the main obstacles for the use of cadavers as a training model is the difficulty in introducing a sufficient pneumoperitoneum to distend the abdominal wall and provide a proper working space that matches that in an anaesthetised patient. The purpose of this study was to describe a fresh human cadaver model for laparoscopic training without requiring a pneumoperitoneum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS AND RESULTS

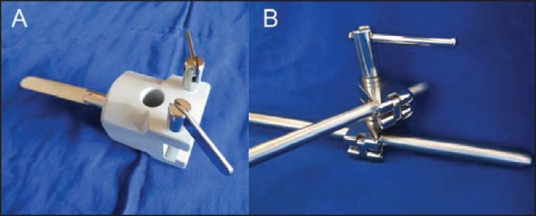

A fake abdominal wall device was developed to allow for laparoscopic training without requiring a pneumoperitoneum in cadavers. The device consists of a table-mounted retractor, two rail clamps [Figure 1a], two independent frame arms, two adjustable handle and rotating features [Figure 1b], and two frames of the abdominal wall (a smaller one that is used as the camera support and a bigger one for the fake abdominal wall) [Figure 2a]. The table-mounted retractor was constructed at a regular surgical material factory.

Figure 1.

(a) Rail clamp with holes for inserting the frame arms (b) Adjustable handle and rotating feature also with holes for inserting the frame arms

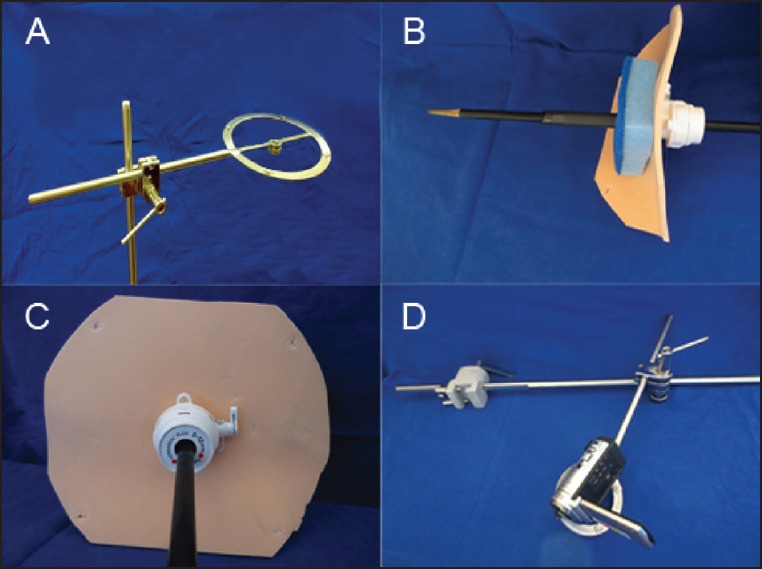

Figure 2.

(a) The bigger frame arm of the fake abdominal wall inserted in the adjustable handle and the rotating feature that moves the arm vertically and horizontally (b) The fake abdominal wall made of a round piece of EVA paper and cleaning sponge with a trocar and a forceps passing through (c) The surgeon's view of the fake abdominal wall. The EVA paper is put over and fixed on the frame arm depicted on Figure 3a (d) A handycam is secured with masking tape on the smaller frame arm

The fake abdominal wall consists of a round piece of ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) paper and cleaning sponge [Figure 2b]. It can be fixed to the frame with small spears on the frame surface. The trocars are passed through the fake abdominal wall as performed in real surgery [Figure 2c]. A regular handycam is fixed on the smaller frame in a similar fashion [Figure 2d].

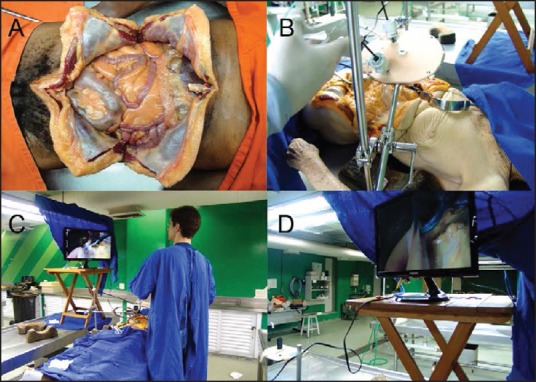

The cadaver is opened with an abdominal cross-shaped incision, allowing for wide access to the abdominal cavity [Figure 3a]. The rail clamp is adapted to a surgical table and the frame arms are mounted such that they can be adapted to many body sizes. The adjustable handle and rotating feature places the fake abdominal wall over the cadaver to block the surgeon's view of the operative field [Figure 3b]. The handycam is fixed over a frame arm, and positioned and connected through a USB connection to a television and dissector; scissors and other laparoscopic materials are positioned inside the trocars [Figure 3c]. The laparoscopic procedure is thus simulated [Figure 3d].

Figure 3.

(a) Cross-shaped incision of the cadaver abdominal wall exposing the peritoneal cavity (b) The adjustable handle and rotating feature places the fake abdominal wall over the cadaver according to the cadaver's size. The surgeon's view of the operative field is blocked by it, and laparoscopic forceps and scissors are positioned inside the trocars (c) The camera is positioned similarly to the fake abdominal wall over the cadaver and connected through a USB connection to a television. The surgeon is positioned laterally (d) The 2D view of the simulated laparoscopic procedure

DISCUSSION

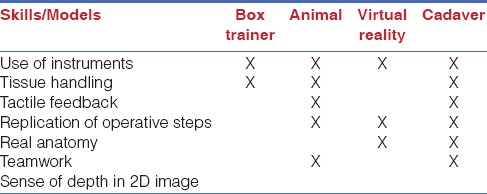

In developing countries, laparoscopy is not widely accessible. Surgeons commonly choose the conventional approach over the laparoscopic approach when there is a lack of equipment and experience.[7,28] Under these circumstances, it is reasonable to infer that developing countries have severe difficulties in training surgeons for laparoscopic procedures. Virtual reality training in laparoscopic surgery is an interesting option and is not too complex to implement into an institutional training programme.[24] However, virtual laparoscopy may be prohibitively expensive for many institutions, and virtual simulators are limited in providing training for some laparoscopic skills, such as teamwork and real tissue-handling feedback.[24] Fortunately, there are other options. Animal models have the same potential for use in advanced surgical skills training. Animal models provide real tissue handling, arterial and venous bleeding, and breathing movements when mechanic ventilation is available. However, animal models are also very expensive because, in addition to the cost of laparoscopic equipment, there is the cost of a structured laboratory and trained personnel to manage the animals. The box trainer is an interesting low-cost alternative for laparoscopic training. The simplicity of the box trainer is an important advantage, allowing for trainees to acquire or build their own devices. Nevertheless, the box trainer is criticised for being unrealistic and very limited as a tool for training in advanced laparoscopic skills.[23] These differences are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of skills in laparoscopic training models

On the other hand, fresh frozen cadavers are generally more accessible; additionally, they offer a high-fidelity laparoscopic simulation model and are an interesting resource for laparoscopic training within the available infrastructure.[24,25,26,27] The cadaver model permits training in all basic laparoscopic skills as follows:

Handling laparoscopic instruments;

Depth perception in a three-dimensional (3D) environment with a 2D view;

Adjustment to the fulcrum effect;

Hand-eye coordination;

Bimanual manipulation; and

Ambidexterity.[24]

Although not usually considered a basic laparoscopic skill, the recognition of real anatomic structures in a 2D view is fundamental; furthermore, compared to other training models, the cadaver offers the best training option.[25,26,27] In addition, the cadaver also allows for training in advanced laparoscopic skills such as teamwork, real tissue handling and replication of the operation steps.[24] Cholecystectomy, colorectal surgeries and other more advanced procedures may be performed on this model.[25,26,27] The cadaver may additionally be appropriate for experimental surgery and for the development of new operative techniques and technologies. It is further possible to reuse the same cadaver for many operations if the cadaver is embalmed with Thiel's preservation solution, which preserves the tissue with the same efficacy as the formaldehyde solution with very small changes to the original colour and consistency.[25] The Achilles’ heel of this approach is the additional cost of Thiel's preservation method, which is very expensive.[25] Additionally, the use of cadavers for laparoscopic training requires real laparoscopic equipment for making a pneumoperitoneum, which means that, although this option is cheaper than the virtual models, the cadaver model includes the costs of video equipment, insufflation equipment and gas carbonic. These tools are not widely accessible in developing countries. Currently, there is a debate about whether laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be practised in the developing world.[28] In Brazil, according to official governmental data, 181,742 cholecystectomies were performed, but only 49,056 (27%) were laparoscopic.[29] The costs of basic materials in these countries, such as a laparoscopic optical system and endoscope, are sometimes prohibitive for hospitals, let alone teaching institutions. In these circumstances, it is reasonable to infer that these countries have severe difficulties in training surgeons in laparoscopy.

The model we describe here may be more accessible for institutions in developing countries that have budget restrictions and are in need of establishing a laparoscopic training programme. The more costly equipment is substituted with material cheaper and easier to acquire. The fake abdominal wall mentioned here consisted of EVA paper and a cleaning sponge, which are inexpensive, disposable materials. This combination of materials was developed to fasten the trocar while moving laparoscopic forceps through the fake abdominal wall. The image was transmitted to a screen using a regular handycam attached to one of the table-mounted retractor's arm frames. This invention addresses the high costs of laparoscopic materials, preventing the need to acquire a laparoscopic optical system, endoscope, endoscopic light source, gas carbonic insufflator and gas carbonic. In addition, it solves the problem of the limitation of space when performing surgery after establishing a pneumoperitoneum, which is a consequence of the rigor mortis of the abdominal wall muscles and distension of the intestine and stomach in the gas-producing decay process.

CONCLUSION

Simulation laparoscopic models have critical importance in allowing surgeons to develop laparoscopic skills without putting patients at risk. Cadavers offer a very promising and useful model for laparoscopic training, albeit with important limitations that are related to the cost and difficulty of implementing their use in training institution programmes. We developed a fake abdominal wall device that overcomes the limitation of space when performing surgery on cadavers and removes the need to acquire more costly laparoscopic equipment. This model is easily accessible at institutions in developing countries, making it one of the most promising tools for teaching laparoscopy.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Daniel Reis Waisberg for helping testing and being a enthusiastic of the project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harrell AG, Heniford BT. Minimally invasive abdominal surgery: Lux et ventas past, present, and future. Am J Surg. 2005;190:239–43. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapron C, Fauoconnier A, Goffinet F, Bréart G, Dubuisson JB. Laparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynaecological pathology: Results of meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1334–442. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.5.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.A prospective analysis of 1518 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. The Southern Surgeons Club. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1073–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104183241601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart R, Ruach M, Magos A. Is laparoscopic surgery really worth it? The view of patients, hospital doctors and health care managers. Gynaecol Endosc. 2001;10:289–96. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu SY, Leighton T, Davis I, Klein S, Lippmann M, Bongard F. Prospective analysis of cardiopulmonary responses to laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1991;1:241–6. doi: 10.1089/lps.1991.1.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wattiez A, Soriano D, Cohen SB, Nervo P, Canis M, Botchorishvili R, et al. The learning curve of total laparoscopic hysterectomy: Comparative analysis of 1647cases. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:339–45. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosser JC, Rosser LE, Savalgi RS. Skill acquisition and assessment for laparoscopic surgery. Arch Surg. 1997;132:200–4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430260098021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Occelli B, Narducci F, Lanvin D, LeBlanc E, Querleu D. Learning curves for transperitoneal laparoscopic and extraperitoneal endoscopic paraaortic lymphadenectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7:51–3. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(00)80009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Voitk AJ. The learning curve in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair for the community general surgeon. Can J Surg. 1998;41:446–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derossis AM, Bothwell J, Sigman HH, Fried GM. The effect of practice on performance in a laparoscopic simulator. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1117–20. doi: 10.1007/s004649900796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Driscoll PJ, Paisley AM, Paterson-Brown S. Video assessment of basic surgical trainees’ operative skills. Am J Surg. 2008;196:265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figert PL, Park AE, Witzke DB, Schwartz RW. Transfer of training in acquiring laparoscopic skills. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:533–7. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soper NJ, Brunt LM, Kerbl K. Laparoscopic general surgery. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:409–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402103300608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emken JL, McDougall EM, Clayman RV. Training and assessment of laparoscopic skills. JSLS. 2004;8:195–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crothers IR, Gallagher AG, McClure N, James DT, McGuigan J. Experienced laparoscopic surgeons are automated to the “Fulcrum effect”: An ergonomic demonstration. Endoscopy. 1999;31:365–9. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guidelines for granting of privileges for laparoscopic and/or thoracoscopic general surgery. Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) Surg Endosc. 1998;12:379–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Society for Bariatric Surgery's guidelines for granting privileges in bariatric surgery. ASBS Bariatric Training Committee. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:65–7. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miskovic D, Wyles SM, Ni M, Darzi AW, Hanna GB. Systematic review on mentoring and simulation in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Ann Surg. 2010;252:943–51. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f662e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Training and assessment of competence. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:721–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birch DW, Bonjer HJ, Crossley C, Burnett G, de Gara C, Gomes A, et al. Consensus Panel Members. Canadian consensus conference on the development of training and practice standards in advanced minimally invasive surgery: Edmonton, Alta., Jun. 1, 2007. Can J Surg. 2009;52:321–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenyon TA, Lenker MP, Bax TW, Swanstrom LL. Cost and benefit of the trained laparoscopic team. A comparative study of a designated nursing team vs a nontrained team. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:812–4. doi: 10.1007/s004649900460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sturm LP, Windsor JA, Cosman PH, Cregan P, Hewett PJ, Maddern GJ. A systematic review of skills transfer after surgical simulation training. Ann Surg. 2008;248:166–79. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318176bf24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aggarwal R, Moorthy K, Darzi A. Laparoscopic skills training and assessment. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1549–58. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma M, Horgan A. Comparison of fresh-frozen cadaver and high-fidelity virtual reality simulator as methods of laparoscopic training. World J Surg. 2012;36:1732–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giger U, Frésard I, Häfliger A, Bergmann M, Krähenbühl L. Laparoscopic training on Thiel human cadavers: A model to teach advanced laparoscopic procedures. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:901–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pattanshetti VM, Pattanshetti SV. Laparoscopic surgery on cadavers: A novel teaching tool for surgical residents. ANZJ Surg. 2010;80:676–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lloyd GM, Maxwell-Armstrong C, Acheson AG. Fresh frozen cadavers: An under-utilized resource in laparoscopic colorectal training in the United Kingdom. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e303–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manning RG, Aziz AQ. Should laparoscopic cholecystectomy be practiced in the developing world? The experience of the first training program in Afghanistan. Ann Surg. 2009;249:794–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a3eaa9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.BRASIL, DATASUS (2014) [Last accessed on 2014 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.datasus.gov.br/DATASUS/datasusphp .