Abstract

Importance

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) are efficacious treatments for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) when given either daily or for half the menstrual cycle during the luteal phase. Preliminary studies suggest SRI treatment can be shortened to the interval between symptom-onset and the beginning of menses.

Objective

Determine the efficacy of symptom-onset dosing with sertraline for treatment of PMDD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted between 2007 and 2012 at three university medical centers. Women with PMDD were instructed to start pills at symptom onset and continue until the first few days of menses for six menstrual cycles.

Intervention

Placebo or sertraline 50–100 mg daily during the symptomatic interval

Main Outcome Measures

Premenstrual Tension Scale (PMTS)(Primary outcome measure), Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology– Clinician-Rated (IDS-C), Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP) (total and subscales), Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scales and Michelson SSRI Withdrawal Symptoms Scale.

Results

125 participants were randomized to sertraline and 127 to placebo. The improvement in IDS-C scores was greater in the sertraline than the placebo group (F(6,1183)=2.6; p=.02; estimated mean difference between intake and endpoint of 5.14 points between groups (95% CI=1.97–8.31)). Group differences in PMTS scores were at a trend level (F(6,448)=2.1; p=.06; estimated mean difference from intake to endpoint of 1.88 between groups (95% CI=0.01–3.75) points). Compared to the placebo group, those assigned to sertraline showed greater improvement on the Total (estimated mean difference of 1.09 points (95% CI=0.96–1.25) and Anger/Irritability subscale of the DRSP (estimated mean difference of 1.22 (95% CI=1.05–1.41) and were more likely to respond ((77 (67%) for sertraline and 65 (53%) for placebo, (Χ2(1)=5.23; p=0.02)). The number of symptomatic days before pill taking diminished over time (F(5,814)=5.3, p<.001) in both groups with no group differences on the Michelson SSRI Withdrawal Symptoms Scale.

Conclusions and Relevance

Women with PMDD may benefit from SRI treatment limited to the interval between the onset of premenstrual symptoms and the first few days of menses. Abrupt treatment cessation at the end of each cycle does not increase risk of discontinuation symptoms.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT00536198

Introduction

A wealth of evidence supports the use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) in the management of PMDD1 either as a daily treatment or one that is restricted to the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.1–14 However, symptoms are typically present for only 4–7 days before the onset of menses,15–17 leading to questions about the potential efficacy of treatments that fit this shorter time frame. Indeed, small studies show that use of an SRI for only one week,8, 14 or initiated at symptom onset, is therapeutic.14, 18–23 There are currently no large, randomized, placebo-controlled trials that assessed the efficacy and response parameters of symptom-onset dosing for PMDD.

With this unique treatment format come questions about feasibility and adverse events. Many women experience difficulty anticipating the onset of symptoms or attribute symptoms to environmental stressors rather than PMDD.15 This can complicate a woman’s ability to determine the optimal time to commence treatment. Additionally, a number of reports cite difficulties with abrupt cessation of SRIs and the emergence of a discontinuation syndrome.24–26 Intermittent treatment for PMDD, by definition, includes treatment that is abruptly stopped although this occurs after a short treatment interval. Thus, a clinical trial of an intermittent treatment would benefit from evaluation of feasibility and risk of discontinuation symptoms.

Herein we report the results of a clinical trial that evaluated symptom-onset dosing of sertraline for the treatment of PMDD. Sertraline is an effective treatment when given only in the luteal phase at doses of 50–100 mg/day.24–26 Our a priori hypothesis was that sertraline, dosed flexibly between 50 mgs and 100 mgs per day during the symptomatic interval, would be feasible and more effective than placebo in the treatment of PMDD. Our assessment includes secondary outcome data on improvement according to emotional and physical domains. Process outcomes, including the interval between symptom onset and pill taking over the course of the trial as a measure of feasibility, and possible discontinuation symptoms are also reported.

METHODS

Study Design and Eligibility

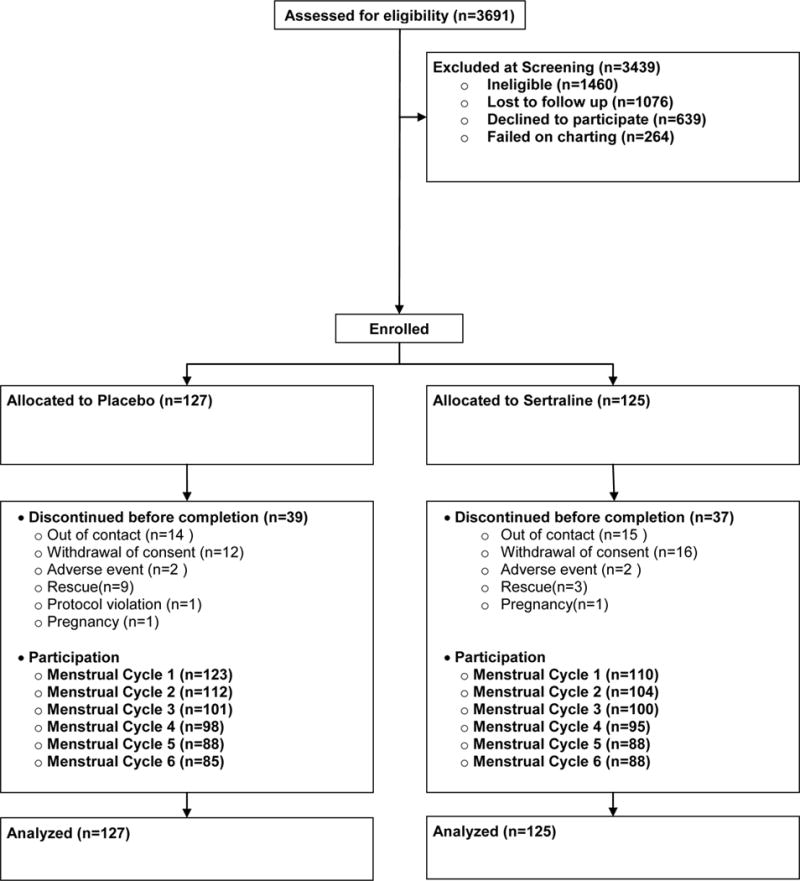

This was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-site, parallel group trial that included a minimum two month pre-trial assessment to confirm a diagnosis of PMDD. Randomized participants were allocated to either sertraline or placebo in a 1:1 ratio, to be taken daily during the symptomatic interval for six menstrual cycles (see Figure 1). Women who did not achieve a CGI-S rating of ≤2 after two months at 100mg or the highest tolerated dose were offered removal from the trial alongside daily sertraline “rescue” treatment. Completers were also offered three months of open-label, daily continuation treatment. Ratings during rescue/continuation treatment were not included in the efficacy analysis.

Figure 1. Study Flow Diagram.

* Randomization occurred between signing consent and the intake visit. Allocation was not disclosed to the participant

Participants

Women were eligible if they: were between 18–48 years; had menstrual cycles 21–35 days and met criteria for PMDD. Women were ineligible if they: currently met criteria for a major depressive episode (MDE) or a substance use condition other than tobacco; had lifetime bipolar disorder, a psychotic illness, or bulimia; had severe suicidal thoughts; were undergoing treatment with a psychotropic medication, an oral contraceptive comprised of drosperinone (an effective treatment for PMDD27), a depot hormonal preparation or intrauterine device that could stop menses; used any oral contraceptive for less than six months prior to screening or did not plan to continue the same hormonal contraceptive throughout the study; used an inadequate birth control method; had a history of hypersensitivity to sertraline; were pregnant or lactating; were planning on re-locating during the study period or were unable or unwilling to provide informed consent. The study was approved by human subjects’ boards at the collaborating institutions.

Randomization and Masking

Randomization and preparation of study pills occurred at Yale. We used a computer-generated randomization list that stratified assignment into block sizes of six and six strata based upon study site and participant use (Y/N) of an oral contraceptive. A research assistant (RA) who had no contact with participants prepared sequentially numbered stock bottles that had no information about the test drug. Sites were sent two lists (Y/N oral contraceptives) specific for their center, and stock bottles. The RA took stock bottles in sequence from the appropriate list and filled a smaller bottle with a medication event monitoring system (MEMS) cap that was given to the participant. The RA replaced pills from the stock bottle at monthly visits, as needed. In this way, masking of study medication was maintained.

Procedures

This study was conducted in New Haven, Connecticut; New York City, New York and Richmond, Virginia. Participants were recruited via flyers, newspaper advertisements and direct mail sent to women aged 18–40 in local zip codes. Respondents completed a brief pre-screening phone interview that included verbal consent. Provisionally eligible women attended a screening office visit wherein we obtained written consent, information about premenstrual symptoms, concurrent medical conditions and use of medications. Study staff gave respondents daily symptom rating forms that were returned weekly. Respondents were allowed to chart symptoms for an additional cycle if one of two cycles did not meet criteria. Participants were reimbursed $15 for the study visit and $50 for completion of daily ratings. Women who did not meet criteria were given treatment referrals.

We used the Daily Rating of Severity of Problems (DRSP)28 to prospectively establish a diagnosis of PMDD. It is comprised of 21 items that reflect the 11 candidate symptoms for PMDD according to DSM IV29 and DSM 5.30 Some symptoms are broken into several component items. Each item is scored 1–6. As in past studies,31 a diagnosis of PMDD required a minimal average luteal phase score of mild (≥ 3 on a 6-point scale) for at least five PMDD symptoms, including at least one mood symptom, during the five most symptomatic of the final luteal phase week and the first two days of menses onset; we required an average follicular phase score be <2 on these same items.

At the baseline visit, subjects were administered the MINI neuropsychiatric interview32 to determine the presence of exclusionary diagnoses. Premenstrual symptom severity was captured through administration of the Premenstrual Tension Scale(PMTS)33 and the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician version (IDS-C)34. A clinician assigned a Clinical Global Impression Severity (CGI-S)35 score and obtained urine for a pregnancy test.

Follow-up visits were 5–7 days after onset of menses wherein we administered measures of premenstrual symptom severity, collected daily ratings, assigned CGI-Improvement (CGI-I) and CGI-S scores and obtained urine pregnancy tests. Visits 5 and 6 were completed over the phone while other visits were face-to-face. Information on adverse events was collected at all visits. At face-to-face visits the RA conducted pill counts and reconciled pill taking with the chart and the MEMs cap.

The starting dose of sertraline was 50 mgs per day (two capsules) to be taken once daily during the symptomatic interval. Daily ratings were reviewed at each visit with the participant to estimate when premenstrual symptoms were likely to occur. Participants were instructed to begin taking sertraline when they first noticed onset of their typical premenstrual symptoms and asked to cease taking pills within a few days of their menstrual flow and around the time symptoms typically ended. The MEMS caps recorded whether the bottle was opened and participants recorded the days they took pills.

Participants who had an inadequate response (a CGI-S of >2) were instructed to increase their dose to a maximum dose of four capsules (100 mgs of sertraline). Participants were instructed to titrate by two capsules every two days to the final dose of 4 capsules and follow the reverse schedule to end dosing. Women who reported moderate to severe side effects, were allowed to reduce pills to one capsule (25 mgs of sertraline) but to increase pills at the next cycle unless rate-limiting side effects continued. Participants were reimbursed $65 for time, transportation and completion of daily symptom ratings.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the PMTS; secondary measures included the IDS-C, DRSP and the Michelson SSRI Withdrawal Scale. The PMTS is a 10-item scale (range 0–36)33, 36 that includes items for irritability-hostility, tension, efficiency, dysphoria, motor coordination, mental-cognitive function, eating habits, social impairment, sex drive, and physical symptoms.33 The IDS-C has 28 items34 (range 0–84) and detects appropriate variations in mood between follicular and luteal phases in subjects with PMDD.37 The PMTS and IDS-C were rated for the 7 days prior to menses. The DRSP total score was generated by computing the mean of each item over the final five days of the luteal phase and summing the 21 items.

Secondary outcomes included global change in illness severity and improvement according to the CGI-S and CGI-I scales, respectively.35 The ranges for both were 1–7, with 7 as most severe and least improvement. Additionally, “responders” were those who achieved a “1 or 2” on the CGI-I scale; remitters achieved a “1”.

We evaluated possible discontinuation symptoms by adding items from the Michelson SSRI withdrawal scale24 to the daily charting form that contained the DRSP. The Michelson items were summed for the three days after pill taking ended for each menstrual cycle.

The subscales from the DRSP and secondary outcomes were scored using the days and methods outlined above for the full DRSP. Items were grouped into a Depressive symptoms subscale (felt depressed, felt hopeless, felt worthless or guilty, slept more, trouble sleeping, felt overwhelmed), a Physical symptom subscale (breast tenderness, bloating, headache, joint or muscle pain) and an Anger/Irritability subscale (Anger/Irritability, conflicts with people). In prior work, internal consistency of these subscales (Cronbach’s α) were found to be 0.90, 0.76 and 0.90, respectively.28, 31

Inter-rater reliability was maintained throughout the trial via videotapes. The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was at 0.8 or higher.

Statistical Approach

The distributions of all continuous variables were examined prior to analysis. No transformations were necessary. For the comparison of sertraline and placebo groups, we used linear mixed effects models for the dependent measures of PMTS, IDS-C and DRSP scores (total and subscale scores) and the Michelson Withdrawal Symptom scale. We used generalized estimating equations for the ordinal CGI scales. In each repeated measures model, there were fixed effects of condition (sertraline, placebo), time (month 1–7), the interaction between condition and time, site (Yale, Cornell, VCU) and oral contraceptive use (Y/N). Interactions among the stratification variables, condition and time were considered but dropped from the models when non-significant. The best-fitting correlation structure was selected for each model based on Schwartz Bayesian Information criterion (BIC). Time was treated as a categorical variable, but linear effects of time were tested within each model. Post-hoc comparisons of least square means were performed to explain significant interactions and main effects. For the responder and remission (CGI-I) analysis, we used the observation from the last visit carried forward and the chi square statistic to compare the number of responders by group.

An alpha level of 0.05 was used for all overall tests of main effects and interactions. The sample size calculation was based on the PMTS. We estimated that with 143 subjects per group and a dropout rate of 30%, we had 80% power to detect a medium effect size (d=0.4) for the difference in mean change from baseline to end-point between groups. Such a difference is considered clinically meaningful.

We conducted an exploratory analysis to determine changes in the interval between symptom onset and initiation of pill-taking over the course of the trial. We computed the mean number of symptomatic days from the DRSP after applying the following conventions. A day was considered symptomatic if a woman had at least three symptoms, each with a severity score of at least three. We conducted sensitivity analyses that used five symptoms but the results were not substantially different (data available upon request). The mean number of symptomatic days prior to pill taking in each cycle was compared for groups, over time, by linear mixed effects models.

Adverse events experienced by participants were tabulated and groups were compared with the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test if the cell size was less than five.

Results

Recruitment occurred between September 2007 and February 2012, the first randomization on November 6, 2007, last randomization on February 20, 2012 and final visit on July 9, 2012. Screening, randomization and retention are illustrated in Figure 1. Participant characteristics are provided in Table 1. We note a slight imbalance between groups in the percentages of participants with at least a college education.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, by Random Assignment

| Characteristic | Active (N=125) N (%) |

Placebo (N=127) N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (μ, years) | 33.7 | 34.6 |

| Race | ||

| White | 86 (68.8) | 89 (70.1) |

| Black | 19 (15.2) | 20 (15.7) |

| Hispanic | 15 (12.0) | 13 (10.2) |

| Asian/mixed/other | 5 (4.0) | 5 (3.9) |

| Education | ||

| Missing | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Some high school/high school graduate | 11 (8.8) | 11 (8.7) |

| Some college | 40 (32.0) | 22 (17.3) |

| College/graduate or professional school | 73 (58.4) | 94 (74.0) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 51 (40.8) | 42 (33.1) |

| Living w partner | 14 (11.2) | 20 (15.7) |

| Divorced/separated | 11 (8.8) | 14 (11.0) |

| Never married | 49 (39.2) | 51 (40.2) |

| Past Psychiatric Conditions | ||

| Major Depressive Disorder | 35 (28.0) | 43 (33.8) |

| Baseline Length of Menstrual Cycle (μ±sd, days) | 27.9±5.1 | 27.0±4.6 |

| Baseline Luteal Phase Daily Rating of Severity of Problems Score (μ±sd,) | 61.2±20.1 | 60.4±17.4 |

Overall, 75% of participants completed the trial or were moved to rescue treatment. Groups had similar retention, although more participants in the placebo (n=9) than the sertraline (n=3) group were moved to rescue treatment.

The difference between sertraline and placebo in rates of change for the PMTS scores was at a trend level (F(6,448)=2.1; p=0.06) with an estimated mean group difference in change from baseline to end-point of 1.88 points (95% CI=0.01–3.75). Compared with placebo, those in the sertraline group showed greater improvement in IDS-C scores over time, F(6,1183)=2.6; p=.02 (Table 2) with an estimated mean difference from intake to endpoint of 5.14 points (95% CI=1.97–8.31).

Table 2.

Menstrual Cycle Symptom Scores for Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures, by Random Assignment

| Number of Participants | PMTS | IDS-C | CGI-S | CGI-I | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit | Act. | Pla. | Active | Placebo | Active | Placebo | Active | Placebo | Active | Placebo |

| Baseline | 125 | 127 | 22.3 (4.8) | 21.4 (4.5) | 35.4 (10.7) | 32.8 (10.4) | 4.5 (0.7) | 4.5 (0.6) | – | – |

| Cycle 1 | 110 | 123 | 15.6 (7.3) | 16.8 (6.0) | 23.7 (12.3) | 24.0 (11.4) | 3.4 (1.0) | 3.8 (0.9) | 2.7 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.0) |

| Cycle 2 | 104 | 112 | 14.1 (6.9) | 15.6 (6.1) | 21.0 (11.7) | 22.8 (10.6) | 3.1 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.1) |

| Cycle 3 | 100 | 101 | 13.0 (8.0) | 14.0 (5.8) | 19.2 (13.1) | 19.6 (10.0) | 2.8 (1.3) | 3.0 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.0) |

| Cycle 4 | 95 | 98 | 12.9 (6.7) | 13.9 (6.3) | 17.3 (11.1) | 19.1 (9.9) | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.3) |

| Cycle 5 | 88 | 85 | 11.4 (6.3) | 12.4 (6.3) | 15.2 (9.9) | 16.7 (10.4) | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.2) |

| Cycle 6 | 88 | 88 | 11.7 (6.8) | 12.8 (6.9) | 15.5 (10.7) | 17.8 (11.0) | 2.2 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.3) | 1.8 (0.9) | 2.2 (1.3) |

| Average Change from Baseline | 88 | 88 | −10.6 (6.6) | −8.9 (7.4) | −20.0 (11.4) | −15.3 (12.5) | −2.3 (1.2) | −1.9 (1.4) | −0.9 (1.2)** | −0.8 (1.4)** |

| Group | F(1,249)=1.6, p=0.21 |

F(1,245)=0.4, p=0.54 |

χ2(1)=6.2, p=0.01 |

χ2(1)=6.7, p=0.01 |

||||||

| Time | F(6,447)=131.8, p<.001 |

F(6,1210)=60.7, p<.001 |

χ2(6)=182.8, p<.001 |

χ2(5)=29.9, p<.001 |

||||||

| Group by Time | F(6,448)=2.1, p=0.06 |

F(6,1183)=2.6, p=0.02 |

χ2(6)=7.5, p=0.28 |

|||||||

| Estimated Mean difference from baseline to end point between active vs. placebo (95% CI) | 1.88 (0.01 – 3.75) | 5.14 (1.97 – 8.31) | 0.59 (0.30 – 1.19) | 0.55 (0.30 – 1.02)* | ||||||

Represents difference between groups at end-point only

Represents average change from Cycle 1 to end-point

Secondary outcomes showed that groups did not differ on the CGI severity scale, although the CGI-Improvement scale favored sertraline (χ2(1)=6.7; p=0.01). The changes in the total DRSP and the Anger/Irritability subscale of the DRSP were greater for the active treatment than placebo group (estimated mean difference for change from baseline to end-point of 1.09 (95% CI=0.96–1.24; p=0.02) for total DRSP and 1.22 (95% CI=1.05–1.41; p<0.01) for irritability, but there were no differences between conditions in the Depression and Physical subscales(Table 4). Seventy seven (67%) and 65 (53%) participants in the sertraline and placebo groups, respectively, responded (χ2(1)=5.23; p=0.02); remission was attained by 48 (43%) and 39 (31%) in the sertraline and placebo group, respectively (χ2 (1)=2.73; p=0.10). There was no interaction between treatment response and hormonal contraceptive use on any of the continuous outcome measures. Table 3 shows that the number of symptomatic days between symptom onset and the initiation of pill-taking shortened significantly for both groups over the course of the trial (F(5, 814)=5.3; p<.001).

Table 4.

Total and Subscale Scores for the Daily Rating of Severity of Problems, by Random Assignment

| Number of Participants | Total DRSP | Depression Subscale | Physical Subscale | Anger/Irritability Subscale |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit | Act. | Pla. | Active | Placebo | Active | Placebo | Active | Placebo | Active | Placebo |

| Baseline | 113 | 115 | 60.3 (19.5) | 59.5 (17.3) | 7.5 (4.0) | 7.2 (3.5) | 10.6 (3.6) | 10.6 (3.9) | 6.4 (2.2) | 6.3 (2.1) |

| Cycle 1 | 104 | 110 | 43.7 (17.4) | 46.1 (17.2) | 5.5 (3.0) | 5.7 (8.4) | 8.4 (3.5) | 8.4 (3.6) | 4.1 (1.9) | 4.6 (2.1) |

| Cycle 2 | 95 | 104 | 38.7 (15.8) | 44.4 (17.5) | 4.8 (2.7) | 4.9 (2.4) | 8.2 (3.7) | 8.8 (3.8) | 3.5 (1.7) | 4.5 (2.3) |

| Cycle 3 | 87 | 89 | 36.8 (15.7) | 40.7 (14.7) | 4.6 (2.7) | 4.6 (2.0) | 7.8 (3.2) | 8.1 (3.4) | 3.3 (1.7) | 4.0 (1.9) |

| Cycle 4 | 81 | 74 | 35.3 (12.2) | 36.9 (11.3) | 4.3 (1.9) | 4.3 (1.5) | 7.4 (3.2) | 7.3 (2.8) | 3.2 (1.4) | 3.8 (1.6) |

| Cycle 5 | 76 | 64 | 31.7 (10.5) | 35.2 (12.7) | 3.9 (1.6) | 4.2 (1.8) | 6.9 (2.7) | 7.1 (3.0) | 2.9 (1.3) | 3.5 (1.7) |

| Cycle 6 | 58 | 51 | 32.2 (10.4) | 36.1 (13.6) | 3.9 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.0) | 6.9 (2.6) | 7.4 (2.9) | 2.8 (1.4) | 3.5 (1.5) |

| Average Change from Baseline | 55 | 49 | −29.7 (18.8) | −22.4 (16.0) | −4.0 (4.0) | −2.7 (3.0) | −4.2 (3.8) | −2.9 (3.5) | −3.7 (2.2) | −2.8 (1.9) |

| Group Effect | F(1,273)=0.1, p=0.83 |

F(1,252)=0.8, p=0.37 |

F(1,240)=1.1, p=0.31 |

F(1,228)=11.6, p<.001 |

||||||

| Time Effect | F(6,911)=79.5, p<.001 |

F(6,540)=31.8, p<.001 |

F(6,989)=50.0, p<.001 |

F(6,986)=109.4, p<.001 |

||||||

| Group by time | F(6,911)=2.5, p=0.02 |

F(6,537)=0.6, p=0.73 |

F(6,989)=1.0, p=0.46 |

F(6,986)=3.2, p<0.01 |

||||||

| Estimated Mean difference from baseline to end point between active vs. placebo (95% CI) | 1.09 (0.96 – 1.25) | 1.08 (0.91 – 1.28) | 1.09 (0.96 – 1.23) | 1.22 (1.05 – 1.41) | ||||||

Depressive symptoms included: felt depressed, felt hopeless, felt worthless or guilty, slept more, trouble sleeping, felt overwhelmed. Physical symptoms included breast tenderness, bloating, headache, joint or muscle pain. Anger/irritability included anger/irritability and conflicts with people

Table 3.

Pill Taking Across the Study, by Random Assignment

| Number of days pills were taken | Number of symptomatica days before pills were taken | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit | Active | Placebo | Active | Placebo |

| Cycle 1 | 6.5 (3.4) | 6.6 (3.5) | 2.8 (3.0) | 2.6 (3.0) |

| Cycle 2 | 7.4 (3.3) | 6.7 (3.3) | 2.0 (2.2) | 2.7 (3.1) |

| Cycle 3 | 8.2 (3.7) | 7.1 (3.3) | 1.9 (2.8) | 2.0 (2.7) |

| Cycle 4 | 7.0 (3.8) | 6.9 (3.4) | 2.0 (2.7) | 2.0 (2.9) |

| Cycle 5 | 7.6 (4.0) | 6.7 (3.1) | 1.9 (2.9) | 1.8 (2.4) |

| Cycle 6 | 6.9 (3.8) | 6.1 (3.2) | 1.7 (2.3) | 2.0 (3.2) |

| Average Change from Cycle 1 | 0.3 (4.2) | −0.3 (3.6) | −0.7 (3.4) | −1.0 (3.2) |

| Group effect | F(1,208)=1.1, p=0.30 |

F(1,224)=0.1, p=0.80 |

||

| Time Effect |

F(5,725)=3.6, P<0.01 |

F(5,814)=5.3, p<0.001 |

||

| Group by time | F(5,726)=0.6, p=0.73 |

F(5,815)=1.0, p=0.43 |

||

| Estimated Mean difference from baseline to end point between active vs. placebo (95% CI) | 1.12 (0.92 – 1.35) | 1.11 (0.85 – 1.45) | ||

Symptomatic days were those that participant experienced at least 3 symptoms at a severity of at least “3”.

Both groups endorsed fewer and similar symptoms on the Michelson scale as the trial progressed (F(6,631) = 6.41, p < 0.0001) (eTable 5), suggesting that these scores do not represent medication withdrawal. Adverse events were similar between groups with the following exceptions: 35 (28%) in the sertraline and 15 (12%) in placebo group endorsed nausea (χ2(1)=8.00, p = 0.01); 22 (18%) in the sertraline and 9 (7%) in the placebo group endorsed difficulty sleeping (χ2(1)= 5.45; p = 0.02). No serious adverse events occurred during the trial (eTable 6).

Discussion

In this first large randomized, placebo-controlled study of symptom-onset dosing with an SRI for PMDD, there was a trend in favor of the efficacy of sertraline using the PMTS (p=.06). Compared to placebo, symptom improvement was clearly better with sertraline when measured by the IDS and DRSP. DRSP subscale analysis showed that the Anger/Irritability subscale from the DRSP favored active treatment. Secondary outcomes of improvement and response according to the CGI-I Scale were also significantly greater with sertraline. The totality of our findings support our hypothesis that active treatment with sertraline, even administered for about ~6 days during the symptomatic period, is an effective means by which to treat PMDD, particularly the cardinal symptoms of irritability and anger. Our results are also consistent with smaller studies of symptom onset dosing for premenstrual symptoms.14, 21, 22

The efficacy signal in this study was not as large as PMDD trials using continuous and full luteal cycle sertraline dosing.5, 31 Three potential reasons are: we included symptomatic days prior to onset of pill taking in the luteal phase each month; 2) a possible true lack of effect on depression and somatic symptom dimensions included in the PMTS, IDS-C, and total DRSP scales, and 3) a potentially suboptimal maximal dose of sertraline. In addition, the repeated counseling regarding dosage, timing, and expectation effects of starting pill taking each month could have increased the non specific response levels, which at 53%, was 10–25% higher than rates reported in many full-and half cycle dosing SSRI trials.5, 31 It is also possible that we would have seen significant differences in the PMTS and depression and somatic measures with a larger sample size.

The robust effect on the Anger/Irritability symptoms in this study is in line with other complete luteal phase dosing studies,12, 38, 39 and the hypothesis that Anger/Irritability symptoms are the hallmark of the condition.15, 40–42 The higher standard deviation of DRSP subscale scores for depression and somatic symptoms suggest that these symptoms were less consistently severe than irritability.

A strength of this study is the 6-cycle duration, which allowed us to demonstrate the persistence of response and increased accuracy of pill-taking over time. Clinicians and patients may have concerns about determining when to initiate pill taking. Daily ratings of PMDD symptoms, are likely to familiarize women with their temporal pattern of symptom emergence and enable them to improve recognition of their symptomatic days. We cannot say whether the accuracy of pill taking would have improved without the necessary vigilance that accompanies keeping a daily symptom rating.

Our data support rapid therapeutic action of SRIs for PMDD symptoms.21, 23 Although a partial response can be seen in MDE within a week,43, 44 it is not the norm, and there is no evidence that a response occurs within a few days, as seen in PMDD. Suggested mechanisms of a rapid response are greater sensitivity among PMDD patients to the acute increased availability of synaptic serotonin21, 45, 46 or increased production of allopregnanolone, an anxiolytic neurosteroid produced in greater amounts after SRI treatment.47, 48 Animal studies demonstrate that SRIs increase activity of 3-α hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, the rate-limiting enzyme for allopregnanolone synthesis, independent of serotonin reuptake.49

Symptom onset dosing was well-tolerated. Attrition rates did not differ between groups and rates of adverse events were generally similar. Of note, there was no evidence of withdrawal symptoms after cessation of sertraline treatment each month.

In summary, in this large, multisite, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, symptom onset dosing of sertraline demonstrated efficacy for PMDD. Irritability symptoms were most responsive to symptom onset treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants R01 MH072955 (Dr Yonkers), 1R01 MH072645 (Dr Kornstein), R01 MH072962 (Dr. Altemus), from the National Institute of Mental Health. and UL1 TR000457 (Clinical andTranslational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. . Study drug and matching placebo were donated by Pfizer, Inc. Dr. Kornstein discloses participation in consulting/advisory boards for the following companies: Forest, Lilly, Pfizer, Shire, Naurex, Takeda; research funded by Takeda, Palatin Technologies, Forest, and Roche; and royalties from Guilford Press. Kimberly Yonkers, M.D., Susan Kornstein and Margaret Altemus, M.D. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Ralitza Gueorguieva, Ph.D., Yale University, and Brian Merry, M.S., Yale University conducted the data analysis.

Footnotes

None of the other authors have relationships or activities that are conflicts of interest with the work presented in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Kimberly A. Yonkers, Departments of Psychiatry and Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, Yale University School of Medicine.

Susan G. Kornstein, Department of Psychiatry and Institute for Women’s Health, Virginia Commonwealth University

Ralitza Gueorguieva, Department of Biostatistics, Yale University School of Public Health

Brian Merry, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine

Kari Van Steenburgh, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine

Margaret Altemus, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College

Bibliography

- 1.Marjoribanks J, Brown J, O’Brien PM, Wyatt K. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:Cd001396. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halbreich U, Smoller JW. Intermittent luteal phase sertraline treatment of dysphoric premenstrual syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1997;58:399–402. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jermain DM, Preece CK, Sykes RL, Kuehl TJ, Sulak PJ. Luteal phase sertraline treatment for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Archives of Family Medicine. 1999;8:328–332. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young SA, Hurt PH, Benedek DM, Howard RS. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with sertraline during the luteal phase: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:76–80. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halbreich U, Bergeron R, Yonkers KA, Freeman E, Stout AL, Cohen L, Halbreich U, Bergeron R, Yonkers KA, Freeman E, Stout AL, Cohen L. Efficacy of intermittent, luteal phase sertraline treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2002;100(6):1219–1229. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steiner M, Korzekwa M, Lamont J, Wilkins A. Intermittent fluoxetine dosing in the treatment of women with premenstrual dysphoria. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1997;33:771–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen L, Miner C, Brown E, Freeman E, Halbreich U, Sundell K, McCray S. Premenstrual daily fluoxetine for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a placebo-controlled, clinical trial using computerized diaries. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;100:435–444. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miner C, Brown E, McCray S, Gonzales J, Wohlreich M. Weekly luteal phase dosing with enteric-coated fluoxetine 90 mg in premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clinical Therapeutics. 2002;24:417–433. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)85043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wikander I, Sundblad C, Andersch B, Dagnell I, Sylberstein D, Bengtsson F, Eriksson E. Citalopram in premenstrual dysphoria: is intermittent treatment during luteal phases more effective than continuous medication throughout the menstrual cycle? Journal of Clinical Psychopharmaocology. 1998;18:390–398. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landen M, Sorvik K, Ysander C, Allgulander C, Nissbrandt H, Gezelius B, Hunter B, Eriksson E. A placebo-controlled trial exploring the efficacy of paroxetine for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. Paper presented at: Presented at the APA; 2002; Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gee M, Bellew K, Holland F, Van Erp E, Perera P, McCafferty J. Luteal phase dosing of paroxetine controlled-release (CR) is effective in treating premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Paper presented at: American Psychiatric Association; 2003; San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sundblad C, Hedberg MA, Eriksson E. Clomipramine administered during the luteal phase reduces the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome: A placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;9:133–145. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman E, Rickels K, Sondheimer S, Polansky M, Xiao S. Continuous or intermittent dosing with sertraline for patients with severe premenstrual syndrome or premenstrual dysphoric disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):343–351. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kornstein SG, Pearlstein TB, Fayyad R, Farfel GM, Gillespie JA. Low-dose sertraline in the treatment of moderate-to-severe premenstrual syndrome: efficacy of 3 dosing strategies. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67(10):1624–1632. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearlstein T, Yonkers K, Fayyad R, Gillespie J. Pretreatment pattern of symptom expression in premenstrual dsyphoric disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;85:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sternfeld B, Swindle R, Chawla A, Long S, Kennedy S. Severity of premenstrual symptoms in a health maintenance organization population. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;99:1014–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)01958-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartlage SA, F S, Gotman N, Yonkers KA. Criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Secondary analyses of relevant data sets. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):300–305. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su T-P, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy DL, Rubinow DR. Effect of menstrual cycle phase on neuroendocrine and behavioral responses to the serotonin agonist m-chlorophenylpiperazine in women with premenstrual syndrome and controls. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1997;82:1220–1228. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.4.3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman E, Sondheimer S, Sammel M, Ferdousi T, Lin H. A preliminary study of luteal phase versus symptom-onset dosing with escitalopram for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66(6):769–773. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravindran LN, Woods SA, Steiner M, Ravindran AV. Symptom-onset dosing with citalopram in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD): a case series. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2007;10(3):125–127. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landen M, Erlandsson H, Bengtsson F, Andersch B, Eriksson E. Short Onset of Action of a Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor When Used to Reduce Premenstrual Irritability. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:585–592. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yonkers KA, Holthausen GA, Poschman K, Howell HB. Symptom- onset treatment for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;26:198–202. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000203197.03829.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinberg EM, Cardoso GMP, Martinez PE, Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ. Rapid response to fluoxetine in women with premsnstrual dysphoric disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29(6):531–540. doi: 10.1002/da.21959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michelson D, Fava M, Amsterdam JD, Apter J, Londborg P, Tamura R, Tepner RG. Interruption of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;176:363–368. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baldwin DS, Cooper JA, Huusom AK, Hindmarch I. A double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, flexible-dose study to evaluate the tolerability, efficacy and effects of treatment discontinuation with escitalopram and paroxetine in patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(3):159–169. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000194377.88330.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Geffen EC, Hugtenburg JG, Heerdink ER, van Hulten RP, Egberts AC. Discontinuation symptoms in users of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in clinical practice: tapering versus abrupt discontinuation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(4):303–307. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0921-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yonkers K, Brown C, Pearlstein T, Foegh M, Sampson-Landers C, Rapkin A. Efficacy of a new low-dose oral contraceptive with drospirenone in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:492–501. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000175834.77215.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W. Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): reliability and validity. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2006;9(1):41–49. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (4th) 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epperson CE, S M, Hartlage SA, Eriksson E, Schmidt PJ, Jones I, Yonkers KA. Premenstrual dysphoric disoder: Evidence for a new category for DSM-5. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):465–475. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yonkers KA, Halbreich U, Freeman E, Brown C, Endicott J, Frank E, Parry B, Pearlstein T, Severino S, Stout A, Stone A, Harrison W. Symptomatic improvement of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with sertraline treatment. A randomized controlled trial. Sertraline Premenstrual Dysphoric Collaborative Study Group.[see comment] JAMA. 1997;278(12):983–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janava J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar G. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(S20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steiner M, Haskett RF, Carroll BJ. Premenstrual tension syndrome: The development of research diagnostic criteria and new rating scales. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1980;62:177–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS) Psychometric properties. Psychological Medicine. 1996;26:477–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. 049 HAMD Hamilton Depression Scale. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Health Department of Health, Education and Welfare; 1976. (HEW Publication No. (ADM) 76-338 ed). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steiner M, Streiner D, Steinberg S, Stewart D, Carter D, Berger C. The measurement of premenstrual mood symptoms. J Affective Dis. 1999;53:269–273. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yonkers KA, Gullion C, Williams A, Novak K, Rush AJ. Paroxetine as a treatment for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;16:3–8. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199602000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eriksson E, Ekman A, Sinclair S, Sorvik K, Ysander C, Mattson UB, Nissbrandt H. Escitalopram administered in the luteal phase exerts a marked and dose-dependent effect in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;28(2):195–202. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181678a28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Landen M, Nissbrandt H, Allgulander C, Sorvik K, Ysander C, Eriksson E. Placebo-controlled trial comparing intermittent and continuous paroxetine in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(1):153–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eriksson E, Andersch B, Ho HP, Landen M, Sundblad C. Diagnosis and treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63(S7):16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Angst J, R S, Merikangas K, Endicott J. The epidemiology of perimenstrual psychological symptoms. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104:110–116. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landen M, Eriksson E. How does premenstrual dysphoric disorder relate to depression and anxiety disorders? Depression and Anxiety. 2003;17:122–129. doi: 10.1002/da.10089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uher R, Mors O, Rietschel M, Rajewska-Rager A, Petrovic A, Zobel A, Henigsberg N, Mendlewicz J, Aitchison KJ, Farmer A, McGuffin P. Early and delayed onset of response to antidepressants in individual trajectories of change during treatment of major depression: a secondary analysis of data from the Genome-Based Therapeutic Drugs for Depression (GENDEP) study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(11):1478–1484. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stassen HH, Angst J, Hell D, Scharfetter C, Szegedi A. Is there a common resilience mechanism underlying antidepressant drug response? Evidence from 2848 patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(8):1195–1205. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su T-P, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau MA, Tobin MB, Rosenstein DL, Murphy DL, Rubinow DR. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;16:346–356. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00245-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brzezinski AA, Wurtman JJ, Wurtman RJ, Gleason R, Greenfield J, Nader T. d-fenfluramine suppresses the increased calorie and carbohydrate intakes and improves the mood of women with premenstrual depression. Journal of The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist. 1990;76:296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A. Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine sterospecifically and selectively increase brain neurosteroid content at doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Psychopharmacology. 2004;24:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uzunov DP, Uzunov P, Sheline Y, Costa E, Guidotti Increase in 3a,5a-TH-PROG (ALLO) and 3a-5B-TH-PROG content in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of depressed patients following fluoxetine treatment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(6):3239–3244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griffin L, Mellon S. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors directly alter activity of neurosteroidogenic enzymes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(23):13512–13517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.