Abstract

Zika virus infection has emerged as the world’s newest health threat, linked to microcephaly in infants and Guillain–Barré syndrome in adults. We address the rapid global spread of this disease, and the prospects for successful prevention and treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Zika virus infection (ZVI) has been making headlines as the newest health threat on the world stage. In this article, we address the rapid global spread of this insidious disease, and the prospects for successful prevention and treatment.

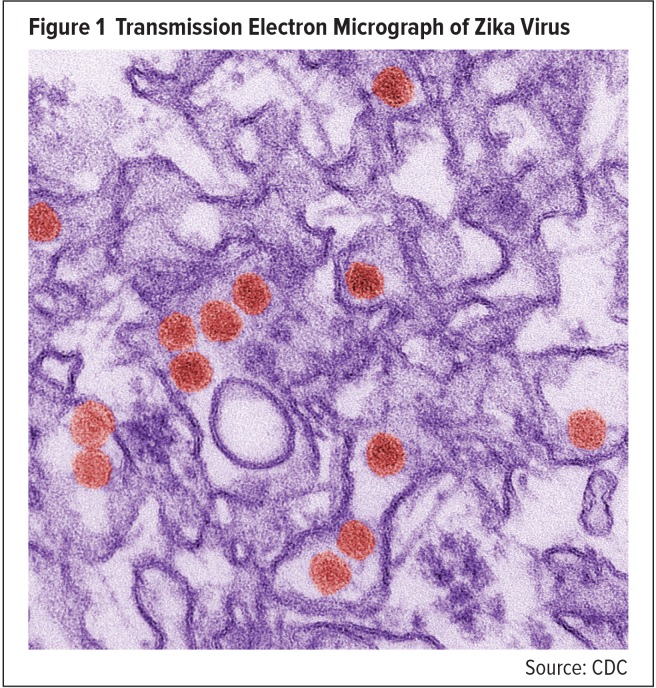

Zika virus (Figure 1) is a mosquito-borne flavivirus (a member of the family Flaviviridae)1 related to yellow fever virus, dengue virus, and West Nile virus.2 It is a single-stranded positive RNA virus (10,794-nt genome) that is transmitted by mosquitoes of the Aedes species—including Ae. africanus, Ae. luteocephalus, Ae. hensilli, Ae. aegypti, and Ae. albopictus—in geographic areas with warm climates, particularly Africa and South America.2,3 In the U.S., Ae. albopictus (Figure 2) has been found as far north as the Great Lakes.4

Figure 1.

Transmission Electron Micrograph of Zika Virus

Source: CDC

Figure 2.

Asian Tiger Mosquito, Aedes albopictus

Source: CDC

The virus was discovered in rhesus monkeys during routine surveillance for yellow fever in the Zika forest near Entebbe, Uganda, in 1947.5 The first cases of ZVI in humans were reported in Uganda and in the United Republic of Tanzania in 1952.6 From the late 1960s to the 1980s, the geographic distribution of the Zika virus expanded to equatorial Asia, including India, Pakistan, Malaysia, and Indonesia.7–10 From Southeast Asia, the infection crossed the Pacific to Yap Island in the Federated States of Micronesia, where the first large outbreak occurred in 2007.11,12 The Zika virus also caused a major epidemic in French Polynesia in 2013–2014, generating thousands of suspected infections.13,14 Neighboring New Caledonia reported imported cases from French Polynesia in 2013 and an outbreak in 2014.15,16

In May 2015, Brazil reported the first cases of locally transmitted ZVI in the Americas.17 Phylogenetic studies found that the closest strain to the one that emerged in Brazil had been isolated during the epidemic in French Polynesia and the Pacific Islands.2 According to one expert, the introduction of Zika virus into Brazil may have been a consequence of the Va’a World Sprint Championship canoe race, held in Rio de Janeiro in August 2014.18 Four Pacific nations (French Polynesia, New Caledonia, Cook Islands, and Easter Island) in which Zika virus was circulating had teams participating in that contest.

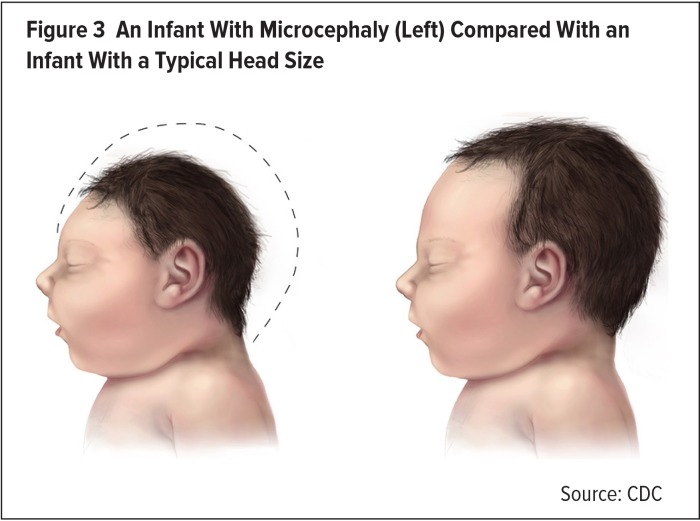

In July 2015, Brazil reported an apparent association between ZVI and Guillain–Barré syndrome in adults.19 In October, Brazil also pointed to a possible link between ZVI and microcephaly (Figure 3) in the infants of infected mothers.20

Figure 3.

An Infant With Microcephaly (Left) Compared With an Infant With a Typical Head Size

Source: CDC

In February 2016, as ZVI spread through the range of Aedes mosquitoes in the Americas, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the disease constituted a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.21 By mid-February 2016, Zika virus transmission had been documented in 48 countries and territories (Table 1).22

Table 1.

Countries and Territories With Local (Autochthonous) Zika Virus Circulation (2007–2016)22

2007–2009

|

As of February 17, 2016

Importantly, 80% of Zika-infected individuals do not become symptomatic.23 Those with symptoms generally experience fever, rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis lasting for up to one week, and the clinical features tend to be mild.24 The virus is expected to be carried worldwide by international travel, far beyond the range of its mosquito vectors.3 In addition, a handful of cases have suggested sexual transmission of the disease by infected men.25–29 Perhaps most troubling, the Zika virus appears to be able to cross the placental barrier in pregnant women, with disastrous consequences for the fetus.30,31 The convergence of these factors makes ZVI a truly global concern.

A timeline summarizing key events in the developing Zika crisis appears as Table 2.32–134

Table 2.

A Timeline of Key Events in the Developing Zika Crisis

1947

|

DIAGNOSIS

Symptomatic adults with ZVI typically present with rash and an elevated body temperature (greater than 98.96° F), along with at least one of the following: arthralgia, myalgia, nonpurulent conjunctivitis, conjunctival hyperemia, headache, or malaise.135 It is difficult to diagnose ZVI, however, because the symptoms are similar to those of dengue and chikungunya viral infections, which are spread via the same mosquitoes that transmit Zika.23,136,137 In addition to dengue and chikungunya, other diagnostic considerations include leptospirosis, malaria, rickettsia, group A Streptococcus, rubella, measles, and parvovirus, enterovirus, adenovirus, and alphavirus infections (e.g., Mayaro, Ross River, Barmah Forest, O’nyong-nyong, and Sindbis viruses).138

ZVI may be suspected based on symptoms and the patient’s recent history (e.g., residence or travel to an area where Zika virus is known to be present), but the clinical diagnosis can be confirmed only by laboratory testing for the presence of Zika virus RNA in the blood or other body fluids, such as urine or saliva.139 Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing should be performed on serum collected within one to three days after symptom onset or on saliva or urine samples collected during the first three to five days after symptom onset.140,141 An RT-PCR for dengue as the main differential diagnosis should be negative.135

Serological tests, including immunofluorescence assays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, may indicate the presence of anti-Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies, which typically develop toward the end of the first week of illness.140,141 These tests must demonstrate an increased antibody titer in paired samples, with an interval of approximately two weeks.135 Test results are usually available four to 14 days after receipt of the specimen.140 Cross-reaction with related flaviviruses, such as dengue, is common in serological assays; therefore, clinicians must view the results with caution.140

Serological assays for Zika antibodies include Anti-Zika Virus ELISA (IgG/IgM) and IIFT Arboviral Fever Mosaic 2 (IgG/IgM) from Germany,142 and Zika Virus Rapid Test from Canada.143 However, no commercially available diagnostic tests have been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the detection of Zika virus.144 In February 2016, Houston Methodist Hospital and Texas Children’s Hospital announced the joint development of the first U.S. rapid Zika test.116 The Texas test is capable of identifying viral DNA in blood, amniotic fluid, urine, or spinal fluid, and can distinguish ZVI from dengue, West Nile, or chikungunya virus infections. Results are obtained within several hours. In addition, a new laboratory test from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has been authorized for emergency use by the FDA. The Zika IgM Antibody Capture Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (Zika MAC-ELISA) is designed to detect antibodies against the Zika virus.121

The CDC has issued guidance for the evaluation of infants or children (up to 18 years of age) with possible ZVI. The agency advises that the testing of infants with possible congenital ZVI who were born to mothers who traveled to or resided in areas affected by Zika virus during pregnancy should be guided by two considerations: 1) whether microcephaly or intracranial calcifications were detected in the infant prenatally or at birth, and 2) the mother’s Zika virus testing results. Acute ZVI should be suspected in an infant or child less than 18 years of age who: 1) has traveled to or resided in an affected area within the past two weeks, and 2) has at least two of the following manifestations: fever, rash, red eyes (conjunctivitis), or arthralgia. Acute ZVI should also be suspected in an infant in the first two weeks of life 1) whose mother traveled to or resided in an affected area within two weeks of delivery, and 2) who has two or more of the following manifestations: fever, rash, conjunctivitis, or arthralgia.112,145

According to the CDC guidelines, the evaluation of infants and children for acute ZVI (symptom onset within the past seven days) should include the testing of serum and, if obtained for other reasons, cerebrospinal fluid specimens for evidence of Zika virus RNA using RT-PCR. If Zika virus RNA is not detected and symptoms suggestive of ZVI have been present for at least four days, the patient’s serum may be tested for Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM) and neutralizing antibodies as well as for dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies. Laboratory evidence of ZVI in a clinical specimen from an infant or child would include detectable Zika virus in culture, Zika virus RNA or antigen, or a clinical specimen positive for Zika virus IgM with confirmatory neutralizing antibody titers at least fourfold higher than dengue virus neutralizing antibody titers. If Zika virus antibody titers are less than fourfold higher than those for dengue virus, test results for Zika virus are considered inconclusive.145

The CDC has also issued guidance for health care providers caring for pregnant women and women of reproductive age who may have been exposed to Zika virus.96 Testing is recommended at the time of illness for pregnant women experiencing symptoms consistent with ZVI. For pregnant women not experiencing such symptoms, testing is recommended when they begin prenatal care. Follow-up testing around the middle of the second trimester of pregnancy is also recommended because of an ongoing risk of Zika virus exposure. Pregnant women should receive routine prenatal care, including an ultrasound during the second trimester of pregnancy. An additional ultrasound may be performed at the discretion of the health care provider. Pregnant women without symptoms of ZVI can be offered testing two to 12 weeks after returning from areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission.

STEPS TO PREVENT VIRUS TRANSMISSION

In response to the growing evidence that ZVI is sexually transmissible, the CDC has recommended that men who reside in or have traveled to an area of active Zika virus transmission and who have pregnant sex partners should consistently use latex condoms during sex (vaginal, anal, or oral) or abstain from sexual activity for the duration of the pregnancy.96

Blood donations are another potential source of Zika virus transmission. The FDA recommends that individuals be deferred from donating blood if they have been to areas with active Zika virus transmission, have potentially been exposed to the virus, or have had confirmed ZVI.23 In areas without active Zika virus transmission, the FDA recommends that donors at risk for ZVI be deferred for four weeks. Individuals considered to be at risk include those who have had symptoms suggestive of ZVI during the past four weeks; those who have had sexual contact with a person who has traveled to or resided in an area with active Zika virus transmission during the prior three months; and those who have traveled to areas with active transmission of Zika virus during the past four weeks.

In areas with active Zika virus transmission, the FDA recommends that whole blood and blood components for transfusion be obtained from areas of the U.S. without active transmission. Blood establishments may continue collecting and preparing platelets and plasma if an FDA-approved pathogen-reduction device is used. The agency’s guidance also recommends that blood establishments update donor-education materials with information about the signs and symptoms of ZVI and ask potentially affected donors to refrain from giving blood.23

The FDA has also identified human cells, tissues, and cellular and tissue-based products (HCT/Ps) as another potential source of Zika virus transmission.124 The agency’s guidance addresses the donation of HCT/Ps from both living and deceased donors, including donors of umbilical cord blood, placenta, or other gestational tissues. HCT/Ps include corneas, bone, skin, heart valves, hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HPCs), gestational tissues (such as amniotic membrane), and reproductive tissues (such as semen and oocytes).

THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES

No specific treatments are available for patients with ZVI.23,134,139 Supportive therapy includes rest and the use of acetaminophen to relieve fever and pain.23 Aspirin should not be given to patients younger than 12 years of age with ZVI because of the risks of bleeding and of developing Reye’s syndrome.135 Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should also be avoided in patients with unconfirmed ZVI in case the symptoms are actually caused by dengue or chikungunya—two infections in which NSAIDs are contraindicated.135 Pruritus may be controlled with antihistamines,135 and patients should drink plenty of fluids to prevent dehydration from sweating and/or vomiting.23,135

According to the CDC, infants with a typical head size, normal ultrasounds, and a normal physical examination born to mothers who traveled to or lived in areas with Zika virus do not require special care beyond what is routinely provided to newborns.112

Researchers have taken tentative steps toward finding a pharmacological treatment for patients with established ZVI. At Utah State University, for example, investigators have evaluated the antiviral activity of ranpirnase, a cancer chemotherapeutic agent, in a cell model of ZVI.146 Overall, the study showed that ranpirnase was active in blocking Zika virus compared with a control. Ranpirnase for injection has been safely administered to more than 1,000 subjects in oncology trials. In another cell-based study, conducted in France, Zika virus appeared to be sensitive to the antiviral effects of both type I and type II interferons.147 But investigators have run into another roadblock: To date, there are no practical animal models against which potential Zika drugs may be screened.148

THE RACE FOR A VACCINE

Although scientists around the world are playing catch-up with the Zika virus,149 they are well versed in the ways of Zika’s relatives, dengue and West Nile. This knowledge has provided a valuable springboard for the development of potential vaccines.150

Brazil’s Butantan Institute, based in São Paulo, was the first group off the starting block, announcing in January that it planned to develop a Zika vaccine “in record time”—although its director warned that the project would likely take three to five years.151 The scientists in São Paulo plan to use animals to produce antibodies to combat the virus. A similar approach was used to develop a treatment for Ebola.152 The National Institutes of Health in the U.S. and the Public Health Agency of Canada have also begun looking for vaccine candidates.149 In January, a Canadian scientist at Laval University in Quebec told Reuters that work on a Zika vaccine could begin as early as August and that, if successful, the vaccine could be available for emergency use as early as October or November 2016, although full regulatory approval would take years.149,153 Also in January, vaccine developer Hawaii Biotech Inc. announced that it had started a formal program to test a Zika virus vaccine in fall 2015, when the virus was first making headlines in Brazil, but the company said it had no timetable for initiating clinical trials.154 Similarly, Inovio Pharmaceuticals, based in Pennsylvania, announced in early 2016 that it had been working on a DNA-based vaccine for the Zika virus since December 2015. In that time, the company has created a DNA strand that could potentially stop the virus, using knowledge acquired from its dengue virus program. Inovio said it planned to move into phase 1 testing in humans by the end of 2016.155

Some heavy hitters on the pharma scene have also entered the vaccine race. In early February, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and Merck said they were evaluating their technologies or existing vaccines for their potential to fight the Zika virus. In Europe, Sanofi announced that it would launch a Zika vaccine program, while in Japan, Takeda said it had formed a team to investigate how it might help make a vaccine.156

In India, biotechnology company Bharat Biotech said that it had started work on a Zika virus vaccine in 2015 while developing vaccines for chikungunya and dengue. The company is now actively developing two vaccine candidates. One is recombinant (i.e., created by genetic engineering), and the other is inactivated. Both are undergoing preclinical trials.157

Meanwhile, at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), scientists are working on a DNA-based Zika vaccine that uses a strategy similar to that of an investigational flavivirus vaccine developed by the agency for West Nile virus. The latter vaccine was able to provoke an immune response in a phase 1 study. The NIAID is also investigating a live-attenuated Zika vaccine, building on an approach used in creating a closely related vaccine for dengue virus. In other work, the agency is using a genetically engineered version of vesicular stomatitis virus—which primarily affects cattle—to develop a third Zika vaccine, which is being evaluated in tissue culture and animal models. The NIAID said it was possible that a vaccine could be ready for early-stage human trials before the end of 2016.150

Currently, the primary target group for Zika vaccines appears to be pregnant women, in view of growing evidence linking the infection to severe birth defects. This may complicate vaccine testing, however, since pregnant women are commonly excluded from clinical trials until the safety of a vaccine or drug has been established in other populations. Moreover, effective vaccines work by provoking an immune response that is sufficiently strong to weaken or destroy the targeted pathogen but not so strong that it sickens the patient. Currently, there is no simple way to determine the optimal immune response for warding off Zika virus.149 Most challenging of all: Since epidemics occur sporadically and with little or no warning, pre-emptively vaccinating large populations in anticipation of Zika outbreaks may be prohibitively expensive.137

ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL EFFORTS

Ultimately, lasting progress won’t be made in the Zika war until the threat is eliminated at its source: virus-carrying mosquitoes. Thus, the prevention and control of ZVI involves two basic strategies: 1) removing or modifying mosquito breeding sites, and 2) eliminating or reducing contact between mosquitoes and people.139 According to the WHO, the latter objective may be achieved by using insect repellent regularly; by wearing clothes (preferably light-colored) that cover as much of the body as possible when outdoors; by using physical barriers, such as window screens and closed doors and windows; and, if needed, by taking additional precautions, such as sleeping under mosquito nets during the day. Insect repellents should contain DEET (N, N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide); IR3535 (3-[N-acetyl-N-butyl]-aminopropionic acid ethyl ester); or icaridin (1-piperidinecarboxylic acid, 2-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-methylpropylester). During outbreaks, health authorities may elect to spray insecticides in affected areas.

In addition, outdoor containers that can hold water, such as buckets and pots, should be emptied and cleaned on a regular basis or covered. Other mosquito-breeding sites, such as roof gutters or used car tires, should be cleaned or removed.139

Several inventive methods are being developed to reduce mosquito populations. In Brazil, researchers are planning to zap millions of male mosquitoes with gamma rays to sterilize them using a device called an irradiator, which has been used to control fruit flies on the Portuguese island of Madeira. The government’s plan is to breed up to 12 million male mosquitoes each week and then sterilize them with the cobalt-60 irradiator. The sterile males will be released into target areas to mate with wild females, which will lay eggs that produce no offspring.158 Releasing sterile irradiated male mosquitoes is a technique that was first developed by the United Nations’ International Atomic Energy Agency to control tsetse flies in Africa.159

Another promising tool is a genetically modified prototype mosquito developed by a British company, Oxitec. The male mosquitoes are modified so that their offspring will die before reaching adulthood and before they are able to reproduce. A WHO advisory group has recommended further field trials of the technique, following promising tests in the Cayman Islands.159

An alternative approach uses Wolbachia bacteria, which prevent the hatching of eggs from female mosquitoes that have mated with infected males. The bacteria do not infect humans. Wolbachia bacteria have been shown to reduce mosquitoes’ ability to transmit the dengue virus. In February, the WHO announced that large-scale field trials of Wolbachia bacteria would start soon.159 Tests of Walbachia bacteria for both Zikaand dengue-carrying mosquitoes are already under way in Indonesia, where scientists are hoping to recruit 100,000 people in 2016. The investigators are faced with two key challenges, however: convincing the public that the trials are safe and securing funding from the government. They estimated that it will take at least three years before results are seen in the field.160

CONCLUSION

As the Zika virus sweeps across Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Americas, ZVI has undergone a correspondingly rapid change from a mild, endemic illness to a world-threatening infection linked to neurological disorders and severe birth defects.3 The transmission of ZVI may be expected to evolve beyond the virus’ mosquito vector to involve person-to-person contact on a global scale, with international travel playing a pivotal role in spread of the disease.3 Pharma companies and research centers around the globe are working feverishly to develop Zika vaccines, although a vaccine worthy of regulatory approval could take years to reach the market.149,151,153

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumo G, Chang GJJ, Tsuchita R, et al. Phylogeny of the genus Flavivirus. J Virol. 1998;72:73–83. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.73-83.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campos S, Bandeira AC, Sardi SI. Zika virus outbreak, Bahia, Brazil [letter] Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1885–1886. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.150847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kindhauser MK, Allen T, Frank V, et al. Zika: the origin and spread of a mosquito-borne virus. Bull World Health Organ. E-pub: 9 Feb 2016. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.171082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Kraemer MUG, Sinka ME, Duda KA, et al. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. ELife. 2015;4:e08347. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dick GW, Kitchen SF, Haddow AJ. Zika virus. I. Isolations and serological specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1952;46:509–520. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(52)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smithburn KC. Neutralizing antibodies against certain recently isolated viruses in the sera of human beings residing in East Africa. J Immunol. 1952;69:223–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchette NJ, Garcia R, Rudnick A. Isolation of Zika virus from Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Malaysia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;18:411–415. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1969.18.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson JG, Ksiazek TG, Suhandiman Triwibowo. Zika virus, a cause of fever in Central Java, Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1981;75:389–393. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(81)90100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson JG, Ksiazek TG, Gubler DJ, et al. A survey for arboviral antibodies in sera of humans and animals in Lombok, Republic of Indonesia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1983;77:131–137. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1983.11811687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darwish MA, Hoogstraal H, Roberts TJ, et al. A sero-epidemiological survey for certain arboviruses (Togaviridae) in Pakistan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77:442–445. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duffy MR, Chen T-H, Hancock WT, Powers AM. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2536–2543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanciotti RS, Kosoy OL, Laven JJ, et al. Genetic and serologic properties of Zika virus associated with an epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1232–1239. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.080287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao-Lormeau VM, Roche C, Teissier A, et al. Zika virus, French Polynesia, South Pacific, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1085–1086. doi: 10.3201/eid2006.140138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mallet HP, Vial AL, Musso D. Bilan de l’épidémie à virus Zika en Polynésie française, 2013–2014. BISES (Bulletin d’information sanitaire épidémiologique et statistique) 2015;13:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth A, Mercier A, Lepers C, et al. Concurrent outbreaks of dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus infections: an unprecedented epidemic wave of mosquito-borne viruses in the Pacific 2012–2014. Euro Surveill. 2014;19:20929. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.41.20929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupont-Rouzeyrol M, O’Connor O, Calvez E, et al. Co-infection with zika and dengue viruses in 2 patients, New Caledonia, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:381–382. doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Society for Infectious Diseases Zika virus—Brazil: confirmed. May 15, 2015. Available at: www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=3370768. Accessed February 19, 2016.

- 18.Musso D. Zika virus transmission from French Polynesia to Brazil (letter) Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1887. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.151125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization Epidemiological update: neurological syndrome, congenital anomalies, and Zika virus infection. Jan 17, 2016. Available at: www.paho.org/hq/indexphp?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=32879&lang=en. Accessed February 19, 2016.

- 20.Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization Epidemiological update: increase of microcephaly in the northeast of Brazil. Nov 17, 2015. Available at: www.paho.org/hq/indexphp?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=32285&lang=en. Accessed February 19, 2016.

- 21.World Health Organization WHO director-general summarizes the outcome of the emergency committee regarding clusters of microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Feb 1, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2016/emergency-committee-zika-microcephaly/en, Accessed February 19, 2016.

- 22.World Health Organization Zika virus, microcephaly, and Guillain-Barré syndrome: situation report. Feb 19, 2016. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204454/1/zikasitrep_19Feb2016_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed February 23, 2016.

- 23.Food and Drug Administration FDA issues recommendations to reduce the risk for Zika virus blood transmission in the United States. Feb 16, 2016. Available at: www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm486359.htm. Accessed February 19, 2016.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Zika virus. Feb 12, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/media/dpk/2016/dpk-zika-virus.html. Accessed February 19, 2016. [PubMed]

- 25.Foy BD, Kobylinski KC, Chilson Foy JL, et al. Probable nonvector-borne transmission of Zika virus, Colorado, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:880–882. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.101939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musso D, Roche C, Robin E, et al. Potential sexual transmission of Zika virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:359–361. doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dallas County Health and Human Services DCHHS reports first Zika virus case in Dallas County acquired through sexual transmission. Feb 2, 2016. Available at: www.dallascounty.org/department/hhs/press/documents/PR2-2-16DCHHSReportsFirstCaseofZikaVirusThroughSexualTransmission.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2016.

- 28.Oster AM, Brooks JT, Stryker JE, et al. Interim guidelines for prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus: United States, 2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:120–121. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6505e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC encourages following guidance to prevent sexual transmission of Zika virus. Feb 23, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0223-zika-guidance.html. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 30.Besnard M, Lastère S, Teissier A, et al. Evidence of perinatal transmission of Zika virus, French Polynesia, December 2013 and February 2014. Euro Surveill. 2014;19:20751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reuters Study suggests Zika can cross placenta, adds to microcephaly link. Feb 17, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-study-idUSKCN0VQ32E. Accessed February 23, 2016.

- 32.MacNamara FN. Zika virus: a report on three cases of human infection during an epidemic of jaundice in Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1954;48:139–145. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(54)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinbren MP, Williams MC. Zika virus: further isolations in the Zika area, and some studies on the strains isolated. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1958;52:263–268. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(58)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson DI. Zika virus infection in man. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1964;58:335–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haddow AD, Schuh AJ, Yasuda CY, et al. Genetic characterization of Zika virus strains: geographic expansion of the Asian lineage. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore DL, Causey OR, Carey DE, et al. Arthropod-borne viral infections of man in Nigeria, 1964–1970. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1975;69:49–64. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1975.11686983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fagbami A. Epidemiological investigations on arbovirus infections at Igbo-Ora, Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 1977;29:187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fagbami AH. Zika virus infections in Nigeria: virological and seroepidemiological investigations in Oyo State. J Hyg (Lond) 1979;83:213–219. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400025997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robin Y, Mouchet J. Serological and entomological study on yellow fever in Sierra Leone. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1975;68:249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jan C, Languillat G, Renaudet J, Robin Y. A serological survey of arboviruses in Gabon. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1978;71:140–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saluzzo JF, Gonzalez JP, Herve JP, Georges AJ. Serological survey for the prevalence of certain arboviruses in the human population of the south-east area of Central African Republic. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1981;74:490–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saluzzo JF, Ivanoff B, Languillat G, Georges AJ. Serological survey for arbovirus antibodies in the human and simian populations of the South-East of Gabon. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1982;75:262–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buathong R, Hermann L, Thaisomboonsuk B, et al. Detection of Zika virus infection in Thailand, 2012–2014. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:380–383. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao-Lormeau VM, Musso D. Emerging arboviruses in the Pacific. Lancet. 2014;384:1571–1572. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61977-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Musso D, Nhan T, Robin E, et al. Potential for Zika virus transmission through blood transfusion demonstrated during an outbreak in French Polynesia, November 2013 to February 2014. Eur Surveill. 2014;19:20761. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.14.20761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization Epidemiological alert: Zika virus infection. May 7, 2015. Available at: www.paho.org/hq/indexphp?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=30075&lang=en. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 47.World Health Organization Zika situation report: neurologic syndrome and congenital anomalies. Feb 5, 2016. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204348/1/zikasitrep_5Feb2016_eng.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 48.Brazilian Ministry of Health Informative Note No. 01/2015: COES microcephaly [in Portuguese] Nov 17, 2015. Available at: www.saude.rs.gov.br/upload/1448404998_microcefalia_nota_informativa_17nov2015_MINISTERIO%20DA%20SAUDE.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 49.European Center for Disease Prevention and Control Communicable Disease Threats Report. Week 47, 15–21 November 2015. Available at: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/communicable-disease-threats-report-21-nov-2015pdf. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 50.European Center for Disease Prevention and Control Microcephaly in Brazil potentially linked to the Zika virus epidemic, ECDC assesses the risk. Nov 25, 2015. Available at: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/press/news/_layouts/forms/News_DispForm.aspx?ID=1329&List=8db7286c-fe2d-476c-9133-18ff4cb1b568&Source=http%3A%2F%2Fecdc.europa.eu%2Fen%2FPages%2Fhome.aspx. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 51.Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization Epidemiological alert: increase of microcephaly in the northeast of Brazil. Nov 17, 2015. Available at: www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=32285=en. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 52.Brazilian Ministry of Health Microcephaly: Ministry releases epidemiological bulletin [in Portuguese] Nov 17, 2015. Available at: http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/index.php/cidadao/principal/agencia-saude/20805-ministerio-da-saude-divulga-boletim-epidemiologico. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 53.World Health Organization Microcephaly—Brazil. Nov 27, 2015. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/27-november-2015-microcephaly/en, Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 54.European Center for Disease Prevention and Control Rapid risk assessment: microcephaly in Brazil potentially linked to the Zika virus epidemic. Nov 24, 2015. Available at: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/zika-microcephaly-Brazil-rapid-risk-assessment-Nov-2015pdf. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 55.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—El Salvador. Nov 27, 2015. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/27-november-2015-zika-el-salvador/en. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 56.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—Mexico. Dec 3, 2015. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/03-december-2015-zika-mexico/en. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 57.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—Venezuela. Dec 3, 2015. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/03-december-2015-zika-venezuela/en. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 58.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—Paraguay. Dec 3, 2015. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/03-december-2015-zika-paraguay/en. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 59.Brazilian Ministry of Health Ministry of Health confirms relationship between Zika virus and microcephaly. Nov 28, 2015. Available at: https://flutrackers.com/forum/forum/south-america/south-america-guillain-barr%C3%A9-microcephaly-zika-virus-tracking/741919-brazil-moh-statement-confirms-relationship-between-zika-virus-and-microcephaly-november-28-2015. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 60.Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization Neurological syndrome, congenital malformations, and Zika virus infection: implication for public health in the Americas. Epidemiological Alert. Dec 1, 2015. Available at: www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&Itemid=&gid=32405=en. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 61.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—Cape Verde. Dec 21, 2015. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/21-december-2015-zika-cape-verde/en. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 62.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—Honduras. Dec 21, 2015. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/21-december-2015-zika-honduras/en. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 63.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—Panama. Dec 22, 2015. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/22-december-2015-zika-panama/en. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 64.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—France—French Guiana and Martinique. Jan 8, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/8-january-2016-zika-france/en. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 65.Marcondes CB, Ximenes MF. Zika virus in Brazil and the danger of infestation by Aedes (Stegomyia) mosquitoes. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. Epub: December 22, 2015. Available at: www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0037-86822015005003102. Accessed February 25, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Avian Flu Diary. Brazil: MOH updates microcephalic birth numbers; Dec 29, 2015. Available at: http://afludiary.blogspot.com/2015/12/brazil-moh-updates-microcephalic-birth.html. Accessed February 25, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention First case of Zika virus reported in Puerto Rico. Available at: www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2015/s1231-zika.html. Accessed February 25, 2015.

- 68.World Health Organization Microcephaly—Brazil. Jan 8, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/8-january-2016-brazil-microcephaly/en. Accessed February 25, 2015.

- 69.Oliveira Melo AS, Malinger G, Ximenes R, et al. Zika virus intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:6–7. doi: 10.1002/uog.15831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—Maldives. Feb 8, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/8-february-2016-zika-maldives/en. Accessed February 25, 2015.

- 71.Enfissi A, Codrington J, Roosblad J, et al. Zika virus genome from the Americas. Lancet. 2016;387:227–228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ventura CV, Maia M, Bravo-Filho V, et al. Zika virus in Brazil and macular atrophy in a child with microcephaly. Lancet. 2016;387:228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Branswell H. Zika virus likely tied to Brazil’s surge in babies born with small heads, CDC says. Stat News. Jan 13, 2016. Available at: www.statnews.com/2016/01/13/zika-brazil-cdc-testing. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 74.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—Guyana, Barbados, and Ecuador. Jan 20, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/20-january-2016-zika-guyana-barbados-ecuador/en. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 75.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC issues interim travel guidance related to Zika virus for 14 countries and territories in Central and South America and the Caribbean. Jan 15, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0315-zika-virus-travel.html. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 76.State of Hawaii Department of Health Hawaii Department of Health receives confirmation of Zika infection in baby born with microcephaly. Jan 15, 2016. Available at: http://health.hawaii.gov/news/files/2013/05/HAWAII-DEPARTMENT-OF-HEALTH-RECEIVES-CONFIRMATION-OF-ZIKA-INFECTION-IN-BABY-BORN-WITH-MICROCEPHALY.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 77.World Health Organization Zika virus: news and updates. Jan, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/timeline-update/en/index1.html. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 78.World Health Organization Guillain-Barré syndrome—El Salvador. Jan 21, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/21-january-2016-gbs-el-salvador/en. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 79.World Health Organization Guillain-Barré syndrome—Brazil. Feb 8, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/8-february-2016-gbs-brazil/en. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 80.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—United States of America—United States Virgin Islands. Jan 29, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/29-january-2016-zika-usa/en. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 81.Reuters. U.S. issues treatment guidelines for infants exposed to Zika. Jan 26, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-usa-babies-idUSKCN0V423F. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 82.Reuters Virginia resident who traveled abroad tests positive for Zika virus. Jan 26, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-virginia-idUSKCN0V500N. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 83.Reuters Most U.S. efforts to fight Zika virus to be informational: White House. Jan 27, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-usa-white-house-idUSKCN0V52FG. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 84.Reuters Deformed babies also suffering eye damage linked to Zika in Brazil. Jan 29, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-eyesight-idUSKCN0V703U. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 85.World Health Organization Zika virus infection—region of the Americas. Feb 8, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/8-february-2016-zika-americas-region/en. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 86.Reuters Exclusive: Brazil says Zika virus outbreak worse than believed. Feb 2, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/health-zika-brazil-exclusive-idUSKCN0VA33F. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 87.World Health Organization Zika virus: news and updates. Feb, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/timeline-update/en. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 88.Reuters New York to offer free Zika tests. Feb 1, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-idUSKCN0VA3O1. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 89.Reuters First U.S. Zika virus transmission reported, attributed to sex. Feb 3, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-idUSKCN0VB145. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 90.Reuters Zika worries Olympic committee, Brazil sees dip in travel. Feb 2, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-olympics-idUSKCN0VB1KY. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 91.Reuters Australia reports two cases of Zika virus, detects mosquitoes at Sydney airport. Feb 2, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-australia-idUSKCN0VB178. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 92.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC emergency operations center moves to highest level of activation for Zika response. Feb 3, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0208-zika-eoca-activation.html. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 93.World Health Organization WHO calls for further investigation into sexual spread of Zika virus. Feb 3, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-who-idUSKCN0VC158. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 94.Reuters UK to spray insecticide inside planes from Zika-affected regions—Guardian. Feb 4, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/health-zika-planes-idUSL3N15K17H. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 95.Reuters Zika found in saliva, urine in Brazil; U.S. offers sex advice. Feb 5, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-idUSKCN0VD2QF. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 96.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC issues interim guidelines for preventing sexual transmission of Zika virus and updated interim guidelines for health care providers caring for pregnant women and women of reproductive age with possible Zika virus exposure. Feb 5, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0205-zika-interim-guidelines.html. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 97.Reuters Update 1: Puerto Rico declares public health emergency over Zika virus. Feb 5, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/health-zika-puertorico-idUSL2N15K1LO. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 98.Reuters France restricts blood transfusions over Zika virus. Feb 7, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-france-idUSKCN0VG0LW. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 99.Associated Press Obama asking Congress for emergency funding to combat Zika. Feb 8, 2016. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/49c5f168ff214eb2b01ff42730789e44/obama-asking-congress-emergency-funding-combat-zika. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 100.Reuters Exclusive: U.S. athletes should consider skipping Rio if fear Zika—officials. Feb 9, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-usa-olympics-exlusive-idUSKCN0VH0BJ. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 101.Reuters China confirms first case of Zika virus—Xinhua. Feb 10, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/health-zika-china-idUSKCN0VI1VG. Accessed February 25, 2016.

- 102.Reuters Finland has had two cases of Zika virus: official. Feb 10, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-finland-idUSKCN0VJ1EK. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 103.Reuters Corrected—Zika virus may hide in organs protected from the immune system. Feb 16, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/health-zika-immune-idUSL2N15V1C9. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 104.Reuters Zika may linger in semen long after symptoms fade: doctors’ report. Feb 12, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-semen-idUSKCN0VL1N5. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 105.Reuters Guillain-Barré on rise in 5 Latam countries, no proven link to Zika—WHO. Feb 13, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/health-zika-who-guillain-barre-idUSKCN0VM0BO. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 106.Reuters More than 5,000 pregnant women in Colombia have Zika virus: government. Feb 13, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-colombia-idUSKCN0VM0JS. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 107.Reuters Russia reports first case of person infected with Zika virus. Feb 13, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-russia-idUSKCN0VO13U. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 108.Reuters Mexico says six pregnant women infected with Zika. Feb 16, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-mexico-idUSKCN0VP1OK. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 109.Reuters Study suggests Zika can cross placenta, adds to microcephaly link. Feb 17, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-study-idUSKCN0VQ32E. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 110.Reuters Brazil says ‘most’ of confirmed microcephaly cases linked to Zika. Feb 17, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-brazil-idUSKCN0VQ2GG. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 111.Reuters World Bank offers $150 million in financing to Zika-affected countries. Feb 17, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-world-bank-idUSKCN0VR21Y. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 112.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Updated guidelines for healthcare providers caring for infants or children with possible Zika virus infection. Feb 19, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0219-zika-guidelines.html. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 113.Reuters South Africa confirms first case of Zika virus. Feb 20, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zikasafrica-idUSKCN0VT092. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 114.Reuters Cuba deploys 9,000 troops in effort to ward off Zika virus. Feb 22, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-cuba-idUSKCN0VV1EW. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 115.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC encourages following guidance to prevent sexual transmission of Zika virus. Feb 23, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0223-zika-guidance.html. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 116.Texas Children’s Hospital First rapid detection Zika test now available through collaboration with Texas Children’s Hospital and Houston Methodist Hospital. Feb 23, 2016. Available at: www.texaschildrens.org/about-us/news/releases/first-rapid-detection-zika-test-now-available-through-collaboration-texas. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 117.Reuters Czech Republic reports first two cases of Zika virus. Feb 24, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-czech-idUSKCN0VY0WJ. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 118.Reuters Colombia reports ‘probable’ case of microcephaly in aborted fetus. Feb 24, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-colombia-idUSKCN0VX2S9. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 119.Greenwood M. Zika virus linked to stillbirth, other symptoms in Brazil. Yale News. Feb 25, 2016. Available at: http://news.yale.edu/2016/02/25/zika-virus-linked-stillbirth-other-symptoms-brazil. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 120.Samo M, Sacramento GA, Khouri R, et al. Zika virus infection and stillbirths: a case of hydrops fetalis, hydranencephaly, and fetal demise. PloS Negl Trop Dis. Feb 25, 2016. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0004517. Accessed February 26, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 121.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention New CDC laboratory test for Zika virus authorized for emergency use by FDA. Feb 26, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0226-laboratory-test-for-zika-virus.html. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 122.Elgot J. France records first sexually transmitted case of Zika in Europe. The Guardian. Feb 27, 2016. Available at: www.theguardian.com/world/2016/feb/27/zika-france-records-first-sexually-transmitted-case-europe. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 123.Duhaime-Ross A. Zika virus can cause severe neurological disorder, scientists say. The Verge. Feb 29, 2016. Available at: www.theverge.com/2016/2/29/11136252/zika-virus-causes-guillainbarre-syndrome. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 124.Food and Drug Administration FDA issues recommendations to reduce the risk of Zika virus transmission by human cell and tissue products. Mar 1, 2016. Available at: www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm488612.htm. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 125.Reuters Cuba reports first case of Zika in Venezuelan doctor. Mar 2, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-cuba-idUSKCN0W40VL. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 126.Reuters New Zealand investigating possible sexual transmission of Zika virus. Mar 2, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-newzealand-idUSKCN0W50BI. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 127.Reuters Google says its engineers working with UNICEF to map Zika. Mar 3, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-alphabet-idUSKCN0W50OR. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 128.Mécharles S, Herrmann C, Poullain P, et al. Acute myelitis due to Zika virus infection. Lancet. Epub: 3 Mar 2016. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00644-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 129.Reuters White House and states to craft Zika attack plan at summit. Mar 4, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-whitehouse-idUSKCN0W60XM. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 130.Reuters WHO convenes experts amid ‘accumulating evidence’ of Zika link to disorders. Mar 4, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-who-idUSKCN0W618T. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 131.Reuters Research indicates another common mosquito may be able to carry Zika. Mar 4, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-brazil-idUSKCN0W52AW. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 132.Reuters Mosquito spraying may not stop Zika, other methods needed: WHO. Mar 9, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-who-idUSKCN0WB1QU. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 133.Reuters CDC director calls Zika in Puerto Rico a ‘challenge and crisis.’. Mar 9, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-frieden-idUSKCN0WA2V1. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 134.Reuters Brazil says microcephaly cases linked to Zika rise to 4,976. Mar 9, 2016. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/health-zika-brazil-idUSL1N16H1LQ. March 9, 2016. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 135.Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization Epidemiological update: Zika virus infection. 2015 Oct 16; Available at: www.paho.org/hq/indexphp?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=32021&lang=en. Accessed February 19, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sikka V, Chattu VK, Popli K, et al. The emergence of Zika virus as a global health security threat: a review and a consensus statement of the INDUSEM Joint Working Group (JWG) J Global Infect Dis. 2016;8:3–15. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.176140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Fauci AS, Morens DM. Zika virus in the Americas: yet another arbovirus threat. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:601–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1600297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Centers for Disease Control and Infection Zika virus: clinical evaluation & disease. Feb 5, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/zika/hc-providers/clinicalevaluation.html. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 139.World Health Organization Zika virus: fact sheet. Feb, 2016. Available at: www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/zika/en. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 140.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Zika virus: diagnostic testing. Feb 25, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/zika/hc-providers/diagnostic.html. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 141.World Health Organization Zika virus. Jan, 2016. Available at: www.wpro.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs_05182015_zika/en. Accessed February 26, 2016. [PubMed]

- 142.Euroimmun AG. First commercial antibody tests for Zika virus diagnostics now available. Jan 29, 2016. Available at: www.euroimmun.com/index.php?eID=dumpFile&t=f&f=3013&token=6cc0bb2eb7c10f484ae50ad91e69cd6424088529. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 143.Biocan Diagnostics Inc Zika virus rapid test. Dec 25, 2015. Available at: www.zikatest.com/?p=1. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 144.Food and Drug Administration Zika virus response updates from FDA. Mar 2, 2016. Available at: www.fda.gov/EmergencyPreparedness/Counterterrorism/MedicalCountermeasures/MCMIssues/ucm485199.htm#mosquitoes. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 145.Fleming-Dutra KE, Nelson JM, Fischer M, et al. Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for infants and children with possible Zika virus infection—United States, February 2016. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:182–187. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6507e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.PRNewswire Ranpirnase exhibits anti-Zika activity. Feb 22, 2016. Available at: www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/ranpirnase-exhibits-anti-zika-activity-300223469.html. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 147.Hamel R, Dejarnac O, Wichit S, et al. Biology of Zika virus infection in human skin cells. J Virol. 2015;89:8880–8896. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00354-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Halford B. Scientists scramble to develop tools, treatments for Zika virus. Chem Eng News. 2016;94:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Reuters Scientists’ path to usable Zika vaccine strewn with hurdles. Feb 3, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-vaccine-idUSKCN0VB21X. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 150.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Zika virus. Feb 25, 2016. Available at: www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/zika/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 151.Reuters Zika virus set to spread across Americas, spurring vaccine hunt. Jan 25, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-idUSKCN0V30U6. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 152.Reuters Brazilian researchers hope to test Zika virus treatment within a year. Feb 4, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-brazil-treatment-idUSKCN0VD2SD. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 153.Reuters Zika vaccine may be ready for emergency use this year: developer. Jan 29, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-interview-idUSKCN0V704J. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 154.Reuters Race for Zika vaccine gathers momentum as virus spreads. Jan 29, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-who-idUSKCN0V61JB. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 155.Lorenzetti L. Here’s the company that’s the closest to developing a Zika vaccine. Fortune. 2016 Jan 28; Available at: http://fortune.com/2016/01/28/zika-virus-vaccine. Accessed March 4, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 156.Reuters Pfizer, J&J, Merck evaluating technologies for Zika vaccine. Feb 3, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-big-pharma-idUSKCN0VC1EB. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 157.Reuters Bharat Biotech says working on two possible Zika vaccines. Feb 3, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/health-zika-vaccine-idUSKCN0VC12U. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 158.Reuters Brazil to fight Zika by sterilizing mosquitoes with gamma rays. Feb 22, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-radiation-idUSKCN0VV2JK. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 159.Reuters Genes, bugs, and radiation: WHO backs new weapons in Zika fight. Feb 16, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-idUSKCN0VP15D. Accessed March 4, 2016.

- 160.Reuters In Indonesia, an experiment with bacteria to tackle Zika. Feb 5, 2016. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/health-zika-research-idUSL3N15I34P. Accessed March 4, 2016.