Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE:

This study examined the longitudinal association between birth of a sibling and changes in body mass index z-score (BMIz) trajectory during the first 6 years of life.

METHODS:

Children (n = 697) were recruited across 10 sites in the United States at the time of birth. Sibship composition was assessed every 3 months. Anthropometry was completed when the child was age 15 months, 24 months, 36 months, 54 months, and in first grade. Children were classified based on the timing of their sibling’s birth. A piecewise quadratic regression model adjusted for potential confounders examined the association of the birth of a sibling with subsequent BMIz trajectory.

RESULTS:

Children whose sibling was born when they were 24 to 36 months or 36 to 54 months old, compared with children who did not experience the birth of a sibling by first grade, had a lower subsequent BMIz trajectory and a significantly lower BMIz at first grade (0.27 vs 0.51, P value = 0.04 and 0.26 vs 0.51, P value = 0.03, respectively). Children who did not experience the birth of a sibling by the time they were in first grade had 2.94 greater odds of obesity (P value = 0.046) at first grade compared with children who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were between 36 to 54 months old.

CONCLUSIONS:

A birth of a sibling when the child is 24 to 54 months old is associated with a healthier BMIz trajectory. Identifying the underlying mechanism of association can help inform intervention programs.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Having younger siblings is associated with lower obesity risk cross-sectionally. The longitudinal association between birth of a sibling and child BMI has not been established. Whether this association varies by the timing of the sibling’s birth is unknown.

What This Study Adds:

A birth of a sibling when the child is 24 to 36 months or 36 to 54 months old is associated with a lower subsequent BMI z-score trajectory and a lower BMI z-score at first grade.

The rate of obesity among children in the United States continues to be high1 and novel strategies for effective interventions are needed. The home environment is an important venue for intervention programs, and although much work has focused on the association between parenting and obesity,2 the potential role of siblings in shaping obesity risk is not fully understood. Understanding the role of siblings may provide novel intervention strategies by targeting related behaviors and interaction patterns between siblings, as well as between siblings and parents.

Having younger siblings, compared with having older or no siblings, is associated with a lower risk of being overweight and obese cross-sectionally.3–8 However, there is limited understanding of how the birth of a sibling may relate to changes in BMI longitudinally during early childhood. Monitoring changes in child BMI after the birth of a sibling could help further establish the association between having younger siblings and lower child BMI by examining temporality of events. Furthermore, identifying sensitive time periods in the association between the birth of a sibling and child BMI could contribute to the targeting and tailoring of interventions and may inform research investigating the underlying mechanism of the association between the birth of a sibling and lower child BMI. Previous work in other domains of child development provides evidence that the age of a child when a sibling is born moderates the effects of the sibling’s birth on the child’s course of development.9–13 Therefore, the birth interval between the child and his/her younger sibling may be associated with behaviors that influence weight status, such as physical activity.14

The main goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that children who experience the birth of a sibling, compared with those who do not, have a lesser subsequent increase in BMI z-score (BMIz). A secondary goal was to test the hypothesis that the effect varies by the age of the child at the time of the sibling’s birth.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development were used for this analysis. The study sample included 1364 families recruited in 1991 at the time of the child’s birth across 10 sites in the United States. Conditional random sampling was used to prevent selection bias. Inclusion criteria were that the mother was healthy, at least 18 years of age, and an English speaker; the child was a singleton with an uncomplicated delivery; and the family resided within 1 hour of the research site in a relatively safe neighborhood, and was not planning to move.

Children and their families participated in home, laboratory, and phone assessments beginning at birth. For the present analysis, we only included children who had complete anthropometric and sibship composition data at every time point (15 months, 24 months, 36 months, 54 months, and first grade). Of the 1364 participants, 953 had complete sibship composition data, 742 had complete anthropometric data, and 697 had both at all 5 time points. Thus, our final sample size was 697 (52% of total participants). The original sample of 1364 was described in more detail elsewhere.15 The sample of children included in this analysis (n = 697) did not differ from the sample not included (n = 667) with regard to socioeconomic status. However, compared with the sample not included, the sample included in this analysis had a significantly higher percentage of females (52.6% vs 43.8%) and non-Hispanic whites (80.2% vs 76.8%).

Measures

Mothers reported children’s birth weight (grams), which was later converted into z-scores based on national datasets.16 Children’s lengths/heights and weights were measured by using standardized procedures during laboratory visits when the children were 15 months, 24 months, 36 months, and 54 months old, as well as during the spring of the child’s first grade year in school. Weight-for-length and BMI were calculated and age and sex specific weight-for-length z-score and BMIz were calculated based on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reference growth curves.17

Family composition was assessed every 3 months throughout the duration of the study. Mothers were asked whether a new sibling was born since last contact during regularly scheduled telephone contacts or during home interviews that occurred at 15, 24, 36, and 54 months. These data were used to determine whether the child experienced a birth of a sibling as well as the timing of the sibling’s birth.

Additional characteristics for adjusted analysis were identified a priori from the literature. Mothers reported the child’s sex and race/ethnicity, family income and family size when the child was 24 months of age, and maternal years of education at the time of the child’s birth.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted by using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were used to assess sample characteristics. Analyses were performed by using mixed models with random coefficient to account for having repeated weight-for-length z-score/BMIz measures for each individual subject. Both linear and quadratic growth curve models were considered, with quadratic growth having a better fit as assessed by Bayesian Information Criteria. Thus, to model the possible impact of a sibling’s birth on children’s weight-for-length z-score/BMIz during the first 6 years of life, a piecewise quadratic regression model was examined. A piecewise quadratic regression model allows the weight-for-length z-score/BMIz growth curve to be altered in correspondence to a sibling’s birth. To examine how the effect of a sibling’s birth on the child’s weight-for-length z-score/BMIz trajectory varies by the timing of the sibling’s birth, children were classified into the following groups: (1) no siblings born by the time the child was in first grade (mean child age 72 months); (2) sibling born when the child was 9 to 24 months old (mean child age 16.5 months); (3) sibling born when the child was 24 to 36 months old (mean child age 30 months), and; (4) sibling born when the child was 36 to 54 months old (mean child age 45 months). There was insufficient follow-up time to examine changes in BMIz attributed to the birth of a sibling between 54 months and first grade. For children who had more than one sibling born during the 6-year period, weight-for-length z-score/BMIz data after the birth of the second sibling were not included in the analysis. Therefore, any modification in weight-for-length z-score/BMI trajectory would be attributed to the birth of 1 sibling. To further assess the association of a sibling’s birth during the first 6 years of life with children’s weight status, we used a multiple logistic regression model to estimate the prevalence of obesity at 72 months for each sibling category and test for differences. All analyses were adjusted for child sex (male versus female) and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white versus Hispanic or not white), income-to-needs ratio (calculated by dividing the total reported family income by the official federal poverty line for a family of that size in that particular year), and maternal years of education. Each of these characteristics has been previously associated with fertility choices and parity18–20 as well as child weight status.1 Significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

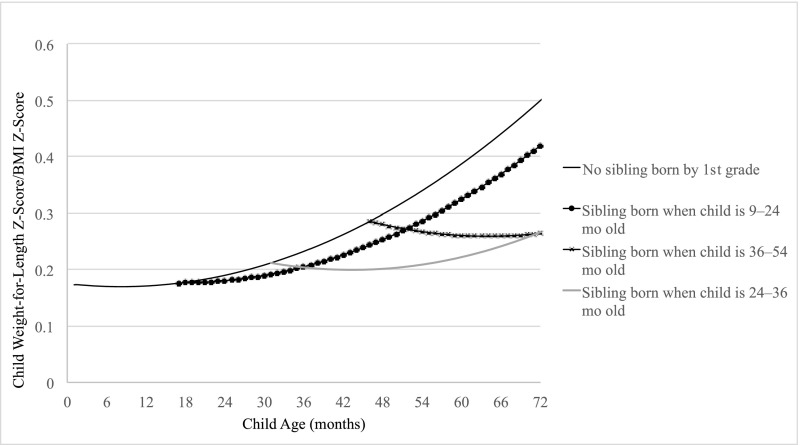

Sample characteristics for the whole sample and stratified by having or not having a sibling by first grade are shown in Table 1. Figure 1 shows changes in weight-for-length z-score and BMIz from birth to first grade, as well as the possible effect of the age of the child when the sibling was born on child weight-for-length z-score/BMIz trajectory. Adjusting for covariates, the birth of a sibling when the child was between 9 months and first grade was associated with lower child BMIz at first grade. Children who did not experience the birth of a sibling by the time they were in first grade had a quadratic growth curve from birth to first grade, such that BMIz did not change during the first 24 months, and then increased between 24 months and first grade.

TABLE 1.

Sample Characteristics for the Whole Sample and Stratified by Having or Not Having a Sibling by First Grade

| Variables | Total (n = 697) | Children With No Siblings Born by First Grade (n = 402) | Children With a Sibling Born by First Grade (n = 295) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 330 (47.4) | 184 (45.8) | 146 (49.5) |

| Female | 367 (52.6) | 218 (54.2) | 149 (50.5) |

| Child race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 559 (80.2) | 323 (80.4) | 236 (80.0) |

| Hispanic or not white | 138 (19.8) | 79 (19.7) | 59 (20.0) |

| Income-to-needs ratio when child aged 24 mo, M (SD) (n = 691) | 3.86 (2.89) | 3.71(2.62) | 4.08 (3.22) |

| Maternal education (years), M (SD) | 14.60 (2.42) | 14.59(2.42) | 14.66 (2.42) |

| Weight-for-length Z-ccore/BMIz, M (SD) | |||

| 15-mo | 0.25 (0.92) | 0.25 (0.94) | 0.25 (0.94) |

| 24-mo | 0.15 (0.90) | 0.20 (0.91) | 0.09 (0.89) |

| 36-mo | 0.15 (0.99) | 0.19 (1.01) | 0.10 (0.97) |

| 54-mo | 0.37 (0.99) | 0.41(1.00) | 0.31 (0.97) |

| 72-mo | 0.42 (1.08) | 0.52 (0.96) | 0.28 (1.24) |

Table shows means (M) and SD or counts (n) and percentages (%).

FIGURE 1.

Child weight-for-length z-score/BMI z-score trajectory from birth to first grade.

The magnitude of effect varied by the age of the child when a sibling was born. Children who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were ages 9 to 24 months had a lower subsequent increase in BMIz compared with children who did not experience the birth of a sibling by the time they were in first grade. However, children who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were ages 9 to 24 months did not have a significantly lower BMIz at first grade compared with children who did not experience the birth of a sibling by the time they were in first grade (0.47 vs 0.51, P value = 0.53). Children who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were 24 to 36 months old had a significantly lower subsequent increase in BMIz and a significantly lower BMIz at first grade compared with children who did not experience the birth of a sibling by the time they were in first grade (0.27 vs 0.51, P value = 0.04). Similarly, children who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were 36 to 54 months old had a significantly lower subsequent increase in BMIz and a significantly lower BMIz at first grade compared with children who did not experience the birth of a sibling by the time they were in first grade (0.26 vs 0.51, P value = 0.03). There was no difference in BMIz at first grade between children who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were 24 to 36 months old versus those who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were 36 to 54 months old (P value = 0.97).

Children who did not experience the birth of a sibling by the time they were in first grade had the highest prevalence of obesity at 12.8%. Children who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were 36 to 54 months old had the lowest prevalence at 4.8%. The prevalence of obesity was 7.8% for children who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were 9 to 24 months old and 8.4% for children who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were 24 to 36 months old. The difference in obesity prevalence between children who did not experience the birth of a sibling by the time they were in first grade versus children who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were 36 to 54 months old was statistically significant (odds ratio = 2.94, P value = 0.046); children who did not experience the birth of a sibling by the time they were in first grade had 2.94 greater odds of obesity at first grade compared with children who experienced the birth of a sibling when they were between 36 to 54 months old. No other pairwise comparisons of obesity prevalence at first grade were statistically significant.

Discussion

We found that the birth of a sibling before first grade, especially when the child is 24 months to 54 months old, is associated with a healthier BMIz trajectory from the time of the sibling’s birth to first grade. Our findings are consistent with previous reports from cross-sectional studies that having younger siblings is associated with a lower risk of being overweight and obesity.3–8 To our knowledge, this study is the first to document a longitudinal association between the birth of a sibling and a lesser subsequent increase in BMIz. Although 1 study reported positive child behavior (eg, greater expression of affection and joyful behavior and less aggression) with a birth interval of >2 years between the child and his/her sibling,13 no previous study has reported a differential effect of the birth of a sibling on child BMIz based on the child’s age when his/her sibling was born.

There are several potential mechanisms of association. Changes in parenting practices that are specific to feeding may occur after the sibling is born. For example, because children who do not have siblings (ie, only children) are more likely to experience restrictive feeding behaviors,21 it is possible that parents may lessen their use of restrictive feeding practices after the birth of a sibling, and less restrictive feeding is associated with a lower child obesity risk.22 Furthermore, because children develop long-lasting eating habits and food preferences around the age of 3 years,23 altering feeding behaviors when the child is ∼3 years of age because of the birth of a sibling may contribute to the observed differential effect of the birth of a sibling on child BMIz. It is also possible that after the birth of a sibling, the older child assumes a caregiver or teacher role, which involves facilitation of active play.24,25 This behavior is more prevalent when the siblings are >2 years apart.13 Assuming the role of a leader in active play may contribute to older siblings becoming more physically active, resulting in greater caloric expenditure and maintenance of a healthy weight status.

The strengths of this study include the longitudinal design, which helps further establish the association between the birth of a sibling and lower child BMIz. We were uniquely positioned to examine how the association between the birth of a sibling and child BMIz differs by the age of the child when his/her sibling was born. Moreover, our sample was drawn from 10 sites across the United States, potentially making our findings more generalizable. The limitations of this study include that the data used for the analysis were collected from 1991 to 1998. Future work may consider examining this question in more contemporaneous data sets, as it is possible that secular trends in child obesity and family size, although null or modest,26,27 could alter results. We were unable to test the mechanism of association longitudinally because measures were not available in the data set used. Future longitudinal studies are needed to identify the mechanism of association between the birth of a sibling and child BMI. Furthermore, the number of children from racial/ethnic minorities is relatively limited, and thus the findings may not be generalizable to certain racial/ethnic groups. Interpretation of the results may also be limited by the necessary transition from using weight-for-length z-score to BMIz as the index of adiposity at 24 months. These are the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended indices of adiposity based on weight and length/height at these ages, but the change in index is methodologically challenging. Future studies might consider employing a feasible measure of adiposity that can be used repeatedly across this developmental period. Additionally, children’s birth weights were not objectively measured and thus errors may exist due to reporting bias. Finally, we did not have detailed information on family instability, which may relate to sibship composition. Instability could lead to disruptions in household routines and sleep patterns that are known to have an impact on children’s weights.28

Conclusions

Our findings suggest a novel framework for researchers and practitioners for designing child obesity interventions. Identifying the underlying mechanism for the association between the birth of a sibling, especially when the child is between age 24 months and first grade, and lesser subsequent increases in BMIz could help inform interventions and improve children’s outcomes. For example, behavioral characteristics of the child and his/her family members, such as mealtime behaviors and physical activity, may be evaluated and targeted for children who do not have younger siblings to help prevent excessive weight gain during early childhood. If the birth of a sibling changes behaviors within the family in ways that are protective against obesity, these patterns of behavior could be promoted among families without a younger sibling. For example, if it were determined that the birth of a sibling leads to less restrictive feeding behaviors by parents, interventionists may focus on counseling families of children without younger siblings regarding appropriate feeding strategies. Alternatively, if it were determined that the birth of a younger sibling is followed by healthy increases in active play due to a child playing with his/her younger siblings, interventionists might describe this phenomenon to families in which the youngest child has a high BMI and no younger siblings. Families may be made aware that the research suggests that having a younger sibling seems to lead to more active play, presumably as a result of the children serving as playmates to each other. Therefore, families might consider more actively seeking out same age or slightly younger playmates for these children to replicate the benefits of having a younger sibling. Incorporating such information regarding family structure and related behaviors into prevention and intervention strategies could contribute to efforts that aim to reduce the prevalence of childhood obesity.

Glossary

- BMIz

BMI z-score

- NICHD

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- SECCYD

Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development

Footnotes

Dr Mosli conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted; Drs Corwyn and Bradley designed the data collection instruments, coordinated and supervised data collection, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted; Dr Lumeng designed the study, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted; Dr Kaciroti analyzed the data, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01HD061356. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faith MS, Scanlon KS, Birch LL, Francis LA, Sherry B. Parent-child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obes Res. 2004;12(11):1711–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ochiai H, Shirasawa T, Ohtsu T, et al. Number of siblings, birth order, and childhood overweight: a population-based cross-sectional study in Japan. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:76. Available at: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-12-766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haugaard LK, Ajslev TA, Zimmermann E, Ängquist L, Sørensen TI. Being an only or last-born child increases later risk of obesity. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hesketh K, Crawford D, Salmon J, Jackson M, Campbell K. Associations between family circumstance and weight status of Australian children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2007;2(2):86–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunsberger M, Formisano A, Reisch LA, et al. Overweight in singletons compared to children with siblings: the IDEFICS study. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:e35. Available at: http://www.nature.com/nutd/journal/v2/n7/full/nutd20128a.html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen AY, Escarce JJ. Family structure and childhood obesity, early childhood longitudinal study–kindergarten cohort. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A50 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/May/09_0156.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosli RH, Miller AL, Peterson KE, et al. Birth order and sibship composition as predictors of overweight or obesity among low-income 4- to 8-year-old children. Pediatr Obes. 2015;11(1):40–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart RB, Mobley LA, Van Tuyl SS, Salvador MA. The firstborn’s adjustment to the birth of a sibling: a longitudinal assessment. Child Dev. 1987;58(2):341–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nadelman L, Begun A. The effect of the newborn on the older sibling: mothers’ questionnaires. In: Lamb ME, Sutton-Smith B, eds. Sibling Relationships: Their Nature and Significance Across the Lifespan. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 1982:13–37 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn J, Kendrick C, MacNamee R. The reaction of first-born children to the birth of a sibling: mothers’ reports. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1981;22(1):1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baydar N, Greek A, Brooks-Gunn J. A longitudinal study of the effects of the birth of a sibling during the first 6 years of life. J Marriage Fam. 1997;59(4):939–956 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minnett AM, Vandell DL, Santrock JW. The effects of sibling status on sibling interaction: influence of birth order, age spacing, sex of child, and sex of sibling. Child Dev. 1983;54(4):1064–1072 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jago R, Baranowski T, Baranowski JC, Thompson D, Greaves KA. BMI from 3-6 y of age is predicted by TV viewing and physical activity, not diet. Int J Obes. 2005;29(6):557–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network . Child care and common communicable illnesses: Results from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(4):481–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman MW. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatr. 2003;3(6). Available at: http://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2431-3-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogden CL, Flegal KM. Changes in terminology for childhood overweight and obesity. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2010;No. 25:1–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Vital Statistics Report Births: Final Data for 2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr59/nvsr59_01.pdf. Accessed July 2015 [PubMed]

- 19.Lovenheim MF, Mumford KJ. Do family wealth shocks affect fertility choices? Evidence from the housing market. Rev Econ Stat. 2013;95(2):464–475 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raley S, Bianchi S. Sons, daughters, and family processes: does gender of children matter? Annu Rev Sociol. 2006;32(1):401–421 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosli RH, Lumeng JC, Kaciroti N, et al. Higher weight status of only and last-born children. Maternal feeding and child eating behaviors as underlying processes among 4-8 year olds. Appetite. 2015;92:167–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhee KE, Lumeng JC, Appugliese DP, Kaciroti N, Bradley RH. Parenting styles and overweight status in first grade. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):2047–2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicklas TA, Baranowski T, Baranowski JC, Cullen K, Rittenberry L, Olvera N. Family and child-care provider influences on preschool children’s fruit, juice, and vegetable consumption. Nutr Rev. 2001;59(7):224–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn J. Sibling relationship in early childhood. Child Dev. 1983;54(4):787–811 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brody GH. Siblings’ direct and indirect contributions to child development. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2004;13(3):124–126 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vespa J, Lewis JM, Kreider RM. America’s families and living arrangements. In: Current Population Reports, P20–570. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Appelhans BM, Fitzpatrick SL, Li H, et al. The home environment and childhood obesity in low-income households: indirect effects via sleep duration and screen time. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1160. Available at: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]