Abstract

Azidoformates are interesting potential nitrene precursors, but their direct photochemical activation can result in competitive formation of aziridination and allylic amination products. Here, we show that visible light activated transition metal complexes can be triplet sensitizers that selectively produce aziridines via the spin-selective photogeneration of triplet nitrenes from azidoformates. This approach enables the aziridination of a wide range of alkenes and the formal oxyamination of enol ethers using the alkene as the limiting reagent. Preparative scale aziridinations can be easily achieved in flow.

Keywords: azides, aziridination, nitrenes, photocatalysis, chemoselectivity

Graphical Abstract

A fresh spin on heterocycles. Synthetically useful photochemical aziridinations can be achieved by using a visible light activated transition metal photosensitizer to produce nitrenes exclusively in their chemoselective triplet spin state. A wide range of aliphatic and aromatic alkenes can be readily aziridinated without competitive allylic insertion reactions.

Aziridines are versatile intermediates for the synthesis of nitrogen-containing compounds. 1 Many important natural products also feature aziridines as their principal bioactive functionality. 2 However, methods for aziridine synthesis are somewhat underdeveloped,3 particularly in comparison to the wealth of methods available for epoxide synthesis. The most widely utilized methods for alkene aziridination involve the generation of metallonitrenes from iminoiodinane reagents. 4 These methods, unfortunately, produce stoichiometric haloarene byproducts, and there has consequently been significant interest in the use of alternate nitrene precursors for aziridination reactions.5 Organic azides appear particularly attractive in this regard because they generate nitrenes by expelling dinitrogen as the sole stoichiometric byproduct. Several laboratories, notably including the Zhang6 and Katsuki7 groups, have reported pioneering advances in catalytic aziridination with organoazides. Nevertheless, these processes often require a large excess of alkene, and many methods are limited to styrenic olefins. Thus there remains a need for new approaches to aziridination that utilize organoazides as nitrene precursors.

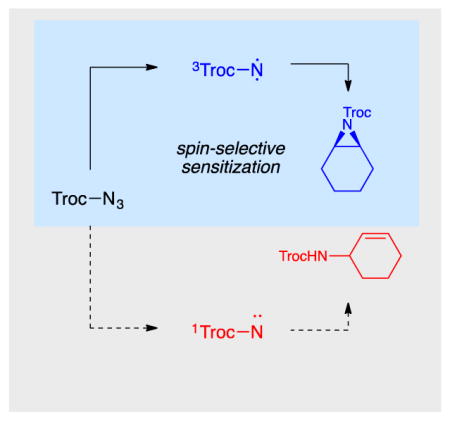

Photochemical activation offers one potential solution. Electronically excited organic azides rapidly decompose to reactive free nitrenes. 8 However, attempts to perform intermolecular aziridination reactions by direct photolysis of azidoformates typically produce complex mixtures containing both aziridines and allylic amination products,9 a result that has led to the pervasive notion that free nitrenes are too reactive to provide synthetically useful chemoselectivities. Seminal studies by Lwowski, however, demonstrated that while singlet carbethoxynitrenes competitively undergo both amination and aziridination reactions, triplet carbethoxynitrenes react selectively with alkenes to afford aziridines with comparatively slow reaction with allylic C–H bonds.10 Thus the fundamental challenge in photochemical aziridination reactions appears not to be the absolute reactivity of free nitrenes but rather the unselective production of both singlet and triplet nitrenes from direct photolysis of azides.

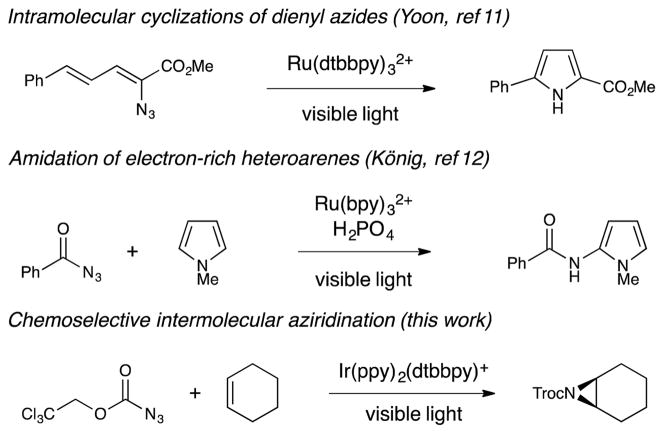

We wondered if chemoselective photochemical aziridination reactions might be achieved via triplet sensitization, which would produce nitrenes selectively in the triplet state. Our laboratory previously studied the use of visible light absorbing transition metal complexes to sensitize vinyl azides towards intramolecular heterocyclic ring-closing reactions (Scheme 1).11 Quite recently, König and coworkers reported an intriguing method for photocatalytic amidation of electron-rich heterocycles, the key step of which was proposed to involve triplet sensitization of a benzoyl azide.12 To the best of our knowledge, however, the use of triplet sensitizers to promote chemoselective intermolecular alkene aziridination reactions has not previously been described. Herein, we demonstrate that visible light triplet sensitization of azidoformates enables the preparation of a range of structurally diverse aziridines. Notably, this method utilizes the alkene as the limiting reagent, provides high yields for both aliphatic and aromatic alkenes, and exhibits excellent selectivity for aziridination over allylic amination.

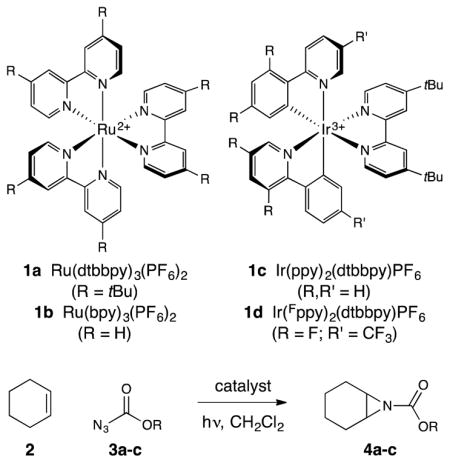

Scheme 1.

Photocatalytic activation of azides via visible light triplet sensitization.

We elected to focus our investigations on azidoformates as nitrene precursors, based on several considerations. First, unlike acyl azides, nitrenes derived from azidoformates have little proclivity to undergo Curtius-type rearrangements that might be competitive with bimolecular aziridination reactions.13 Second, azidoformates are less easily reduced than acyl azides, which should disfavor undesired photoreductive pathways for azide decomposition via non-nitrene-mediated pathways.14 Finally, we computationally estimated the lowest-energy triplet excited state of ethyl azidoformate to be ~54 kcal/mol,15 thermodynamically within a range accessible by the Ir complexes we have previously exploited as energy transfer photocatalysts.11,16

We began by examining the reaction of ethyl azidoformate (0.5 mmol) with cyclohexene (0.1 mmol) in the presence of a range of photoactive Ru(II) and Ir(III) complexes (Table 1, entries 1–4). From this study, Ir(ppy)2(dttbpy)PF6 (1c) emerged as the most effective photocatalyst, providing 17% yield of aziridine after 4 h of irradiation with a 15 W blue LED lamp (entry 3). Notably, we observed no allylic amination nor other products characteristic of uncontrolled nitrene insertion. A screen of azidoformates revealed that introduction of electron-withdrawing substituents increased the rate of aziridination (entries 5 and 6); when 2,2,2-trichloroethyl azidoformate (TrocN3) was used, the consumption of cyclohexene was complete after 4 h, and the aziridine was formed in 77% yield (entry 6).17 Interestingly, an excess of the azide was required only for optimal rate; lowering the azide concentration resulted in a slower reaction, but the mass balance of the azide remained high (entries 7 and 8). Similarly, increasing the reaction scale to 0.4 mmol resulted in partial conversion to the aziridine at 4 h (entry 9), although full conversion could be restored by increasing the reaction time to 20 h (entry 10). These results indicate the reaction is likely photon-limited, consistent with the high molar absorptivity of this class of photocatalysts.18 Control studies showed both catalyst and light (entries 11 and 12) are essential for the reaction to proceed. Finally, in line with our original hypothesis, we studied the direct UV-promoted photochemical reaction (310 nm) of 2 with 3c and observed an unselective mixture of allylic amination and aziridination products, highlighting the value of triplet sensitization for chemoselective aziridination.19

Table 1.

Optimization studies for photocatalytic aziridination. Unless otherwise noted, all reactions were conducted using 0.10 mmol of 2 in degassed solvent and irradiated with a 15 W blue LED flood lamp for 4 h.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Azidoformate (R) | Equiv. azide | Yield[a] |

| 1 | 1a | 3a (–CH2CH3) | 5 | 0% |

| 2 | 1b | 3a (–CH2CH3) | 5 | <2% |

| 3 | 1c | 3a (–CH2CH3) | 5 | 17% |

| 4 | 1d | 3a (–CH2CH3) | 5 | <2% |

| 5 | 1c | 3b (–CH2CH2Cl) | 5 | 50% |

| 6 | 1c | 3c (–CH2CCl3) | 5 | 77% |

| 7 | 1c | 3c (–CH2CCl3) | 3 | 65% |

| 8 | 1c | 3c (–CH2CCl3) | 1 | 41% |

| 9[b] | 1c | 3c (–CH2CCl3) | 5 | 50% |

| 10[b,c] | 1c | 3c (–CH2CCl3) | 5 | 75%[d] |

| 11[e] | 1c | 3c (–CH2CCl3) | 5 | 0% |

| 12 | none | 3c (–CH2CCl3) | 5 | 0% |

Yields determined via 1H NMR analysis using 1,4-bis(trimethylsilyl)benzene as an internal standard unless otherwise noted.

Reaction conducted on 0.40 mmol scale with respect to 2.

Reaction irradiated for 20 h.

Isolated yield.

Reaction conducted in the dark.

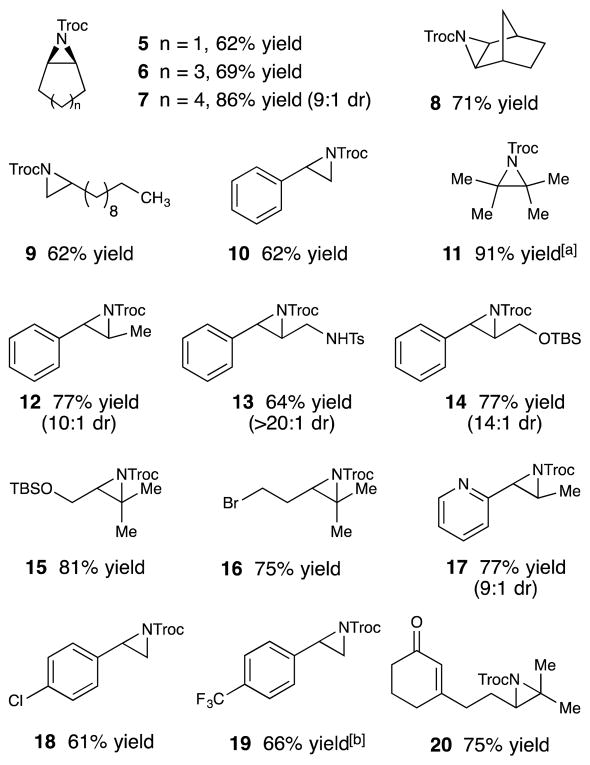

Table 2 summarizes the scope of the photocatalytic aziridination. A variety of cyclic alkenes undergo aziridination smoothly under optimized conditions (5–8). The method provides good yields of aziridines derived from both aliphatic and styrenic alkenes (9 and 10), and internal olefins (11 and 12) undergo aziridination as successfully as terminal alkenes. A variety of functional groups are tolerated including protected amines and alcohols (13–15), potentially photosensitive halides (16), and Lewis basic heterocycles (17). Electron-deficient alkenes react at a slower rate, consistent with the electrophilic nature of the nitrene intermediate, often requiring somewhat extended reaction times (18 and 19). Consistent with this rate difference, a substrate bearing both an α,β-unsaturated ketone and an aliphatic trisubstituted alkene undergoes selective aziridination at the electron-rich alkene (20).

Table 2.

Scope of aziridination products available by photocatalytic activation. Reactions were conducted using 0.40 mmol of alkene in degassed solvent and irradiated with a 15 W blue LED flood lamp for 20 h. Yields represent the averaged values from two reproduced experiments.

Isolated as a 13:1 mixture of aziridine to imine (see SI for more information).

Reaction irradiated for 30 h.

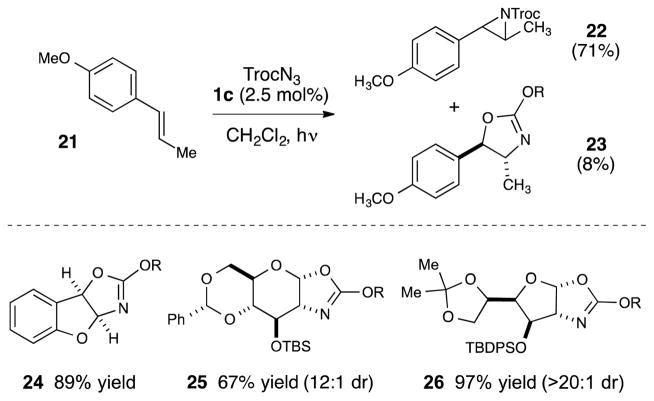

Reactions of alkenes bearing electron-releasing moieties were also explored (Scheme 2); however, the resulting aziridines were formed with varying amounts of an isomeric oxazoline. Anethole, for example, yielded a 9:1 mixture of aziridine 22 and oxazoline 23 in 79% combined yield. We wondered if more electron-rich substrates such as enol ethers might favor the formation of these formal oxyamination products. 20 Indeed, the reaction of benzofuran afforded oxazoline exclusively (24), 21 with no azirdine observable in the reaction mixture. Glycals similarly underwent exclusive oxyamination, yielding 25 and 26 with excellent d.r..

Scheme 2.

Scope of oxazoline products available by photocatalytic activation. (R = –CH2CCl3)

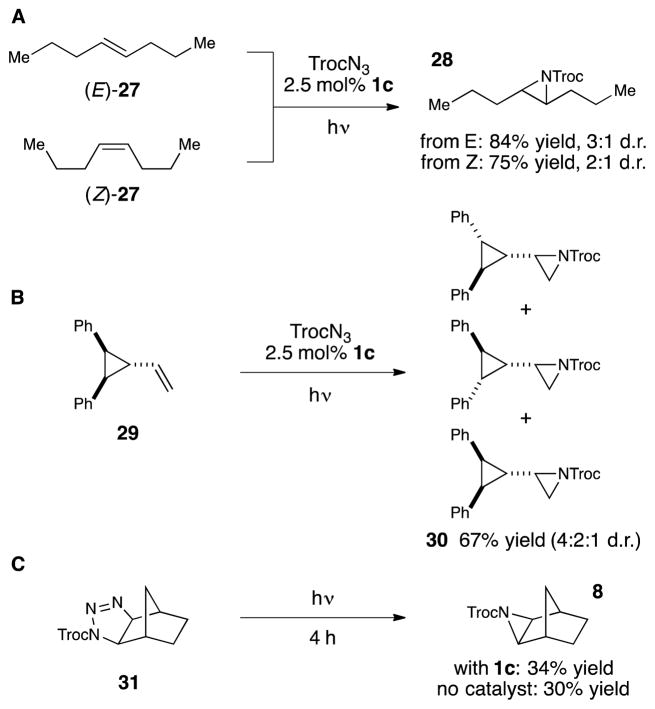

We predicated our reaction design on the hypothesis that triplet nitrenes would be selectively formed via Dexter energy transfer from the triplet excited state of a transition metal photocatalyst.22 Aziridination reactions of triplet nitrenes should proceed in a stepwise fashion involving electrophilic radical addition to an alkene followed by relatively slow intersystem crossing and fast ring-closure of the resulting singlet 1,3-diradical. Consistent with this expectation, aziridinations of stereodefined cis and trans alkenes are not stereospecific (Scheme 3A). The radical nature of the intermediate was further verified by subjecting cyclopropyl alkene 29 to the aziridination conditions (Scheme 3B). This reaction resulted in the scrambling of the cyclopropane stereochemistry in the aziridinated products (30), a result that is only consistent with the reversible ring fragmentation of a cyclopropyl carbinyl radical intermediate.23 Finally, we considered the possibility that the aziridination was not proceeding via a nitrene intermediate but rather by a [3+2] cycloaddition of the carbamoyl azide followed by a photocatalytic decomposition of a 1,2,3-triazoline intermediate.24 To test this hypothesis, we prepared norbornene-derived triazoline 31 and irradiated it for 4 h in the presence and absence of 1c (Scheme 3C). While we observed slow conversion of 31 to aziridine 8, the rate of this spontaneous ring contraction is not impacted by the presence of photocatalyst 1c and is kinetically incompetent to be a significant contributor to the formation of aziridine under catalytic conditions. Thus all available evidence is consistent with the triplet nitrene postulated in our reaction design.

Scheme 3.

Studies supporting a stepwise diradical mechanism for aziridination via a triplet nitrene.

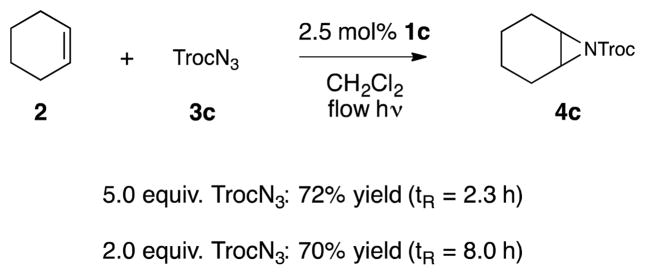

One notable result of our optimization studies was the observation that the rate of azide consumption decreased as the scale of the reaction increased. This phenomenon is consistent with a photon-limited process, which is common in photoreactions that involve chromophores with high molar absorptivity. Such reactions often benefit from flow reactors whose reduced dimensionality can increase the photon flux and allow for efficient scale-up.25 We thus examined the aziridination of cyclohexene in flow and observed significantly increased efficiency, with a high yield and short residence time (tR) of 2.3 h. More importantly, we also observed that the concentration of azide could be lowered to 2.0 equiv in flow, albeit with a somewhat longer residence time (tR = 8 h). Finally, to demonstrate the scalability of the aziridination in flow, we conducted an aziridination reaction on preparative scale and produced 785 mg of pure aziridine in 70% isolated yield over a 16 h period.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that photocatalytic aziridinations can be achieved by using a visible light absorbing transition metal photosensitizer for the spin-selective generation of triplet nitrenes from azidoformates. A wide range of alkenes can be aziridinated or oxyaminated under operationally facile batch conditions, and the use of a flow reactor enables the reaction to be conducted on preparative scale. Further efforts in our lab will continue to develop visible light triplet sensitization as a general, conceptually novel strategy for C–N bond-forming reactions using organoazides as nitrene precursors.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 4.

Aziridination of 2 in flow.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dale Kreitler and Prof. Sam Gellman for the loan of the HPLC pump used in all flow experiments. We thank Yuliya Preger for helpful discussions. We gratefully acknowledge the NIH NIGMS for financial support (GM095666) and Sigma–Aldrich for a generous gift of iridium(III) chloride.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- 1.a) Hu XE. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:2701–2743. [Google Scholar]; b) Huang CY, Doyle AG. Chem Rev. 2014;114:8153–8198. doi: 10.1021/cr500036t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yudin AK, editor. Aziridines and Epoxides in Organic Synthesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Kametani T, Honda T. Adv Heterocycl Chem. 1986;39:3373–3387. [Google Scholar]; b) Botuha C, Chemla F, Ferreira F, Pérez-Luna A. In: Heterocycles in Natural Product Synthesis. Majumdar KC, Chattopadhyay SK, editors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2011. pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Sweeney JB. Chem Soc Rev. 2002;31:247–258. doi: 10.1039/b006015l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Watson IDG, Yu L, Yudin AK. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:194–206. doi: 10.1021/ar050038m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Müller P, Fruit C. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2905–2920. doi: 10.1021/cr020043t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Degennaro L, Trinchera P, Luisi R. Chem Rev. 2014;114:7881–7929. doi: 10.1021/cr400553c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For reviews, see: Katsuki T. Chem Lett. 2005;34:1304–1309.Fantauzzi S, Caselli A, Gallo E. Dalt Trans. 2009:5434. doi: 10.1039/b902929j.Driver TG. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:3831–3846. doi: 10.1039/c005219c.Lu H, Zhang XP. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1899–1909. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00070a.

- 6.a) Gao G-Y, Jones JE, Vyas R, Harden JD, Zhang XP. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6655–6658. doi: 10.1021/jo0609226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ruppel JV, Jones JE, Huff CA, Kamble RM, Chen Y, Zhang XP. Org Lett. 2008;10:1995–1998. doi: 10.1021/ol800588p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jin L-M, Xu X, Lu H, Xui X, Wojtas L, Zhang XP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;20:5309–5313. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Subbarayan V, Ruppel JV, Zhu S, Perman JA, Zhang XP. Chem Commun. 2009:4266–4268. doi: 10.1039/b905727g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Omura K, Murakami M, Uchida T, Irie R, Katsuki T. Chem Lett. 2003;32:354–355. [Google Scholar]; b) Omura K, Uchida T, Irie R, Katsuki T. Chem Commun. 2004;18:2060–2061. doi: 10.1039/b407693a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kawabata H, Omura K, Katsuki T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:1571–1574. [Google Scholar]; d) Kawabata H, Omura K, Katsuki T. Chem Asian J. 2007;2:248–256. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scriven EFV, editor. Azides and Nitrenes, Reactivity and Utility. Academic Press; New York: 1984. pp. 1–291. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lwowski W, Mattingly T. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:1947–1958. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Lwowski W, Woerner FP. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:5491–5492. [Google Scholar]; b) Lwowski W. Angew Chem Int, Ed. 1967;6:897–906. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farney EP, Yoon TP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:793–797. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brachet E, Ghosh T, Ghosh I, König B. Chem Sci. 2015;6:987–992. doi: 10.1039/c4sc02365j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Mandel S, Hadad CM, Platz MS. J Org Chem. 2004;69:8583–8593. doi: 10.1021/jo048433y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Kamlet AS, Steinman JB, Liu DR. Nat Chem. 2011;3:146–153. doi: 10.1038/nchem.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.See Supporting Information for further information regarding the molecular energies and coordinates of these computational studies.

- 16.a) Lu Z, Yoon TP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:10329–10332. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hurtley AE, Lu Z, Yoon TP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:8991–8994. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Organoazide compounds are potentially explosive, and proper safety procedures should always be used in their manipulation. However, samples of TrocN3 stored at 0 °C in our laboratory show no signs of decomposition after several months, and DSC analysis indicates that TrocN3 is stable to 157 °C. See: Lus H, Subbarayan V, Tao J, Zhang XP. Organometallics. 2010;29:389–393.

- 18.Flamigni L, Barbieri A, Sabatini C, Ventura B, Barigelletti F. Top Curr Chem. 2007;281:143–203. [Google Scholar]

- 19.See Supporting Information for details of these experiments.

- 20.Du Bois J, Tomooka CS, Hong J, Carreira EM. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:3179–3180. [Google Scholar]

- 21.König observes the formation of an analogous oxazoline product in two examples. In the reaction of benzoyl azide with benzofuran, the oxazoline is produced as a 2:1 mixture with the C–H amination product in 50% overall yield. See Ref 12.

- 22.Addition of anthracene to an aziridination reaction completely inhibits consumption of the azidoformate, indicating that the excited Ir triplet reacts more rapidly with this triplet quencher than with azidoformate. This experiment, unfortunately, does not elucidate the mechanism by which azidoformate and the photocatalyst interact in the productive reaction.

- 23.a) Müller P, Baud C, Jacquier Y. Can J Chem. 1998;76:738. [Google Scholar]; b) Benkovics T, Du J, Guzei IA, Yoon TP. J Org Chem. 2009;74:5545–5552. doi: 10.1021/jo900902k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Van Humbeck JF, Simonovich SP, Knowles RR, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10012–10014. doi: 10.1021/ja1043006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.For an example of the formation of aziridines by decomposition of triazolines, see: Scheiner P. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:4759–4760.

- 25.For review see: Garlets ZJ, Nguyen JD, Stephenson CRJ. Isr J Chem. 2014;54:351–360. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201300136.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.