Abstract

We aimed to define the taxonomic status of 16 strains which were phenetically congruent with Acinetobacter DNA group 15 described by Tjernberg & Ursing in 1989. The strains were isolated from a variety of human and animal specimens in geographically distant places over the last three decades. Taxonomic analysis was based on an Acinetobacter-targeted, genus-wide approach that included the comparative sequence analysis of housekeeping, protein-coding genes, whole-cell profiling based on matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), an array of in-house physiological and metabolic tests, and whole-genome comparative analysis. Based on analyses of the rpoB and gyrB genes, the 16 strains formed respective, strongly supported clusters clearly separated from the other species of the genus Acinetobacter. The distinctness of the group at the species level was indicated by average nucleotide identity values of ≤82 % between the whole genome sequences of two of the 16 strains (NIPH 2171T and NIPH 899) and those of the known species. In addition, the coherence of the group was also supported by MALDI-TOF MS. All 16 strains were non-haemolytic and non-gelatinase-producing, grown at 41 °C and utilized a rather limited number of carbon sources. Virtually every strain displayed a unique combination of metabolic and physiological features. We conclude that the 16 strains represent a distinct species of the genus Acinetobacter, for which the name Acinetobacter variabilis sp. nov. is proposed to reflect its marked phenotypic heterogeneity. The type strain is NIPH 2171T ( = CIP 110486T = CCUG 26390T = CCM 8555T).

At the time of writing, the formal classification of the genus Acinetobacter includes 33 distinct species with validly published names (http://www.bacterio.net/a/acinetobacter.html) and several species with effectively published names awaiting validation (e.g. Krizova et al., 2014; Smet et al., 2014). The real diversity of the genus at the species level, however, extends far beyond this existing classification as indicated by reports on groups of genomically related strains that did not belong to any of the named species (Touchon et al., 2014). Already the early taxonomic studies of Bouvet & Grimont (1986), Bouvet & Jeanjean (1989) and Tjernberg & Ursing (1989) have revealed several such putative taxa based on DNA–DNA hybridization (DDH) studies, with some of them still lacking formal classification. One of these taxa, DNA group 15, was delineated by Tjernberg & Ursing (1989) among Acinetobacter isolates recovered from human and environmental specimens received from hospitals and outpatient clinics in the city of Malmö, Sweden. This group encompassed two strains, one isolated from urine and the other from faeces. Based on DDH, the two strains appeared to represent a novel genomic species (gen. sp.) clearly separated from the validly or provisionally named species known at that time. Human clinical isolates genotypically congruent with these strains have been reported, although rarely, by later studies (Nemec et al., 2000; van den Broek et al., 2009). Moreover, Poirel et al. (2012) recently described a number of carbapenem-resistant isolates from faeces of cattle, which appeared to belong to DNA group 15 sensu Tjernberg & Ursing based on rpoB gene comparative analysis.

The present study aimed to define the taxonomic status of 16 strains that were genotypically congruent with DNA group 15 sensu Tjernberg & Ursing. For this purpose, we used a combination of taxonomic methods, which has been recently optimized to delineate novel species within the genus Acinetobacter(Krizova et al., 2014). This Acinetobacter-targeted, genus-wide approach includes the comparative sequence analysis of two housekeeping, protein-coding genes (rpoB and gyrB), whole-cell profiling based on whole-cell matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), a comprehensive array of in-house physiological and metabolic tests, and whole-genome comparative analysis performed on selected strains. The obtained results revealed that the 16 strains represented a both phenetically and phylogenetically coherent taxon, which was well-separated at the species level from all hitherto known species of the genus Acinetobacter. Given the relatively high number of strains isolated at different places over a long time period, we feel appropriate to formally name this taxon; the name Acinetobacter variabilis sp. nov. is proposed, which is used throughout the following text.

The 16 strains of Acinetobacter variabilis sp. nov. used in this study are listed in Table 1. Of these, 11 strains were recovered from a variety of human clinical specimens at different geographical locations over the last three decades. The remaining five strains were recently isolated from faeces of cattle at a dairy farm in France (Poirel et al., 2012). The diversity of the 16 isolates at the strain level was indicated by the sequence heterogeneity of the rpoB and gyrB genes (Fig. 1) and was confirmed by macro-restriction analysis of genomic DNA (Fig. S1, available in the online Supplementary Material).

Table 1. Strains of Acinetobacter variabilis sp. nov.

Culture collections: CCM, Czech Collection of Microorganisms, Brno, Czech Republic; CCUG, Culture Collection, University of Göteborg, Sweden; CIP, Collection de l'Institut Pasteur, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France. ANC and NIPH, designations used in the Laboratory of Bacterial Genetics (National Institute of Public Health, Prague, Czech Republic).

| Strain designation | Specimen | Location and year of isolation | Donor or reference |

| NIPH 2171T ( = CIP 110486T = CCUG 26390T = CCM 8555T = Tjernberg & Ursing 151aT) | Urine (human) | Malmö, Sweden, 1980s | Tjernberg & Ursing (1989) |

| NIPH 899 ( = CIP 110487) | Conjunctiva (human) | Sedlčany, Czech Republic, 1998 | Nemec et al. (2000) |

| NIPH 2026 ( = CCUG 28276 = Tjernberg & Ursing 118) | Faeces (human) | Malmö, Sweden, 1980s | Tjernberg & Ursing (1989) |

| ANC 4681 | Urine (human) | Bukavu, DR Congo, 2013 | M. Vaneechoutte & M. Irenge |

| ANC 4692 | Blood (human) | Columbia, NY/USA, 2011 | |

| ANC 4693 | Leg (human) | Schenectady, NY/USA, 2012 | |

| ANC 4694 | Blood (human) | Queens, NY/USA, 2012 | |

| ANC 4695 | Leg wound (human) | Rensselaer, NY/USA, 2012 | |

| ANC 4696 | Toe (human) | Albany, NY/USA, 2012 | |

| ANC 4703 | Eye swab (human) | London, Canada, 1988 | D. Gopaul |

| ANC 4723 | Peritoneal dialysis fluid (human) | London, Canada, 1990 | D. Gopaul |

| ANC 4718 | Rectal swab (cow) | France, 2010 | |

| ANC 4720 | Rectal swab (cow) | France, 2010 | |

| ANC 4729 | Rectal swab (cow) | France, 2010 | |

| ANC 4750 | Rectal swab (cow) | France, 2010 | |

| ANC 4771 | Rectal swab (cow) | France, 2010 | |

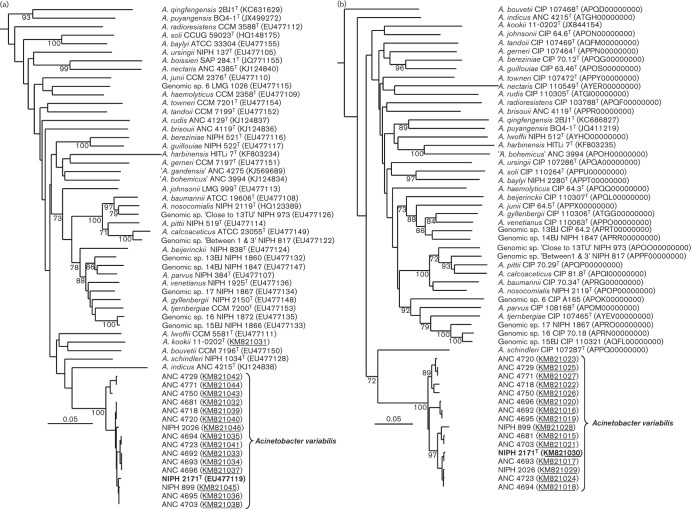

Fig. 1.

Rooted neighbour-joining trees based on partial nucleotide sequences of the (a) rpoB (861 bp) and (b) gyrB (759 bp) genes of 16 strains of Acinetobacter variabilis sp. nov. and the type or reference strains of known species of the genus Acinetobacter. Evolutionary distances were computed using Kimura’s two-parameter model. The sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (derived from GenBank accession no. NC002516) was used as the outgroup. Bootstrap values (>70 %) after 1000 simulations are shown at branch nodes. GenBank accession nos. are given in parentheses (those obtained in this study are underlined). Bars, 5 % of change per nucleotide site. Both rpoB- and gyrB-based clusters encompassing strains of A. variabilis sp. nov. were supported by bootstrap values of 100 % using maximum-parsimony analysis. All calculations were done by the BioNumerics 7.1 software (Applied-Maths).

To determine the taxonomic position of the 16 strains within the genus Acinetobacter, we first performed comparative sequence analysis of the RNA polymerase β-subunit (rpoB) gene, which is currently the best-studied single gene taxonomic and phylogenetic marker for the genus Acinetobacter (Nemec et al., 2009, 2011; Krizova et al., 2014). Similarity calculations and cluster analysis were carried out for the region spanning nucleotide positions 2915 to 3775 of the rpoB coding region of Acinetobacter baumannii CIP 70.34T using BioNumerics 7.1. software (Applied-Maths) with the default parameters. The results of cluster analysis of the rpoB sequences of the 16 strains of A. variabilis sp. nov. and the other species of the genus Acinetobacter are shown in Fig. 1(a). The intra-species pairwise similarity values (expressed as the percentages of identical nucleotides at homologous sequence positions in a multiple alignment) for the strains of A. variabilis sp. nov. were in the range of 96.8–100 %, whereas the similarities between these strains and the other members of the genus had values between 77.1 % (Acinetobacter qingfengensis ANC 4671T) and 90.0 % (Acinetobacter schindleri NIPH 1034T). The distinctiveness of the rpoB sequences of A. variabilis sp. nov. was also supported at the protein level. The amino acid sequences (RpoB positions 973–1258) inferred from nucleotide sequences were identical in all the 16 strains, except for NIPH 2171T with a single amino acid difference (1008E >Q), but differed from those of the other species of the genus Acinetobacter in at least 13 amino acids (A. schindleri NIPH 1034T).

Comparative analysis of the partial sequences of the DNA gyrase subunit B (gyrB) gene was carried out to confirm the genotypic relationship between the 16 strains and their separation from the other members of the genus based on the rpoB sequences as described (Krizova et al., 2014). To obtain the gyrB sequences for the strains of A. variabilis sp. nov., we used PCR amplification and sequencing primers gyrB-F-15TU (5′-CTAACCATTCATCGCGCCGG-3′) and gyrB-R-15TU (5′-CGAGTGCGCTCTTACGACGG-3′), which were inferred from the whole genome sequences of strains NIPH 2171T (GenBank accession no. APRS00000000.1) and NIPH 899 (APPE00000000.1). These primers target the region delimited by positions 436 and 1234 of the gyrB coding sequence of strain NIPH 2171T. The obtained gyrB sequences were compared to those of all species of the genus Acinetobacter included in the rpoB analysis except for Acinetobacter boissieri and ‘Acinetobacter gandensis’ for which the gyrB sequence was not available (Fig. 1b). The similarity calculations and cluster analysis were performed for a 759 bp region corresponding to positions 456–1214. The identity values between the A. variabilis sp. nov. strains were 95.4–100 % in contrast to the range from 74.4 % (Acinetobacter nectaris CIP 110549T) to 85.0 % (A. schindleri NIPH 1034T) observed between A. variabilis sp. nov. and the other species of the genus Acinetobacter. These values correspond to the inter- and intra-species similarity values found in our previous study (Krizova et al., 2014).

Genus-wide whole-genome comparative analysis was performed on the sequences of strains NIPH 2171T (GenBank accession no. APRS00000000.1; size 3.48 Mb, no. of contigs 23, no. of proteins 3348, DNA G+C content 40.7 %) and NIPH 899 (APPE00000000.1; size 3.77 Mb, no. of contigs 88, no. of proteins 3731, DNA G+C content 39.3 %), and other species of the genus Acinetobacter, which are all available from the NCBI website under BioProject no. PRJNA183623 (Touchon et al., 2014). Genome sequences were not available for six species (A. boissieri, ‘A. gandensis’, Acinetobacter harbinensis, Acinetobacter kookii, Acinetobacter puyangensis and A. qingfengensis), which were clearly genotypically distinct from A. variabilis sp. nov. at the species level, as shown by the analysis of the rpoB and/or gyrB sequences (Fig. 1). Average nucleotide identity based on blast (ANIb) was calculated using the JSpecies web program (http://imedea.uib-csic.es/jspecies/) with the default settings (Richter & Rosselló-Móra, 2009). The ANIb value between the genome sequences of strains NIPH 2171T and NIPH 899 was 96.32 %, whereas between these two sequences and those of the other Acinetobacter taxa, it ranged from 71.12 % (A. nectaris CIP 110549T, GenBank accession no. AYER00000000.1) to 82.09 % (Acinetobacter lwoffii NIPH 512T, AYHO00000000.1) (Table S1). These values concur with the threshold interval (95–96 %) proposed to discriminate between bacterial species (Richter & Rosselló-Móra, 2009) and further support the distinctiveness of A. variabilis sp. nov. at the species level.

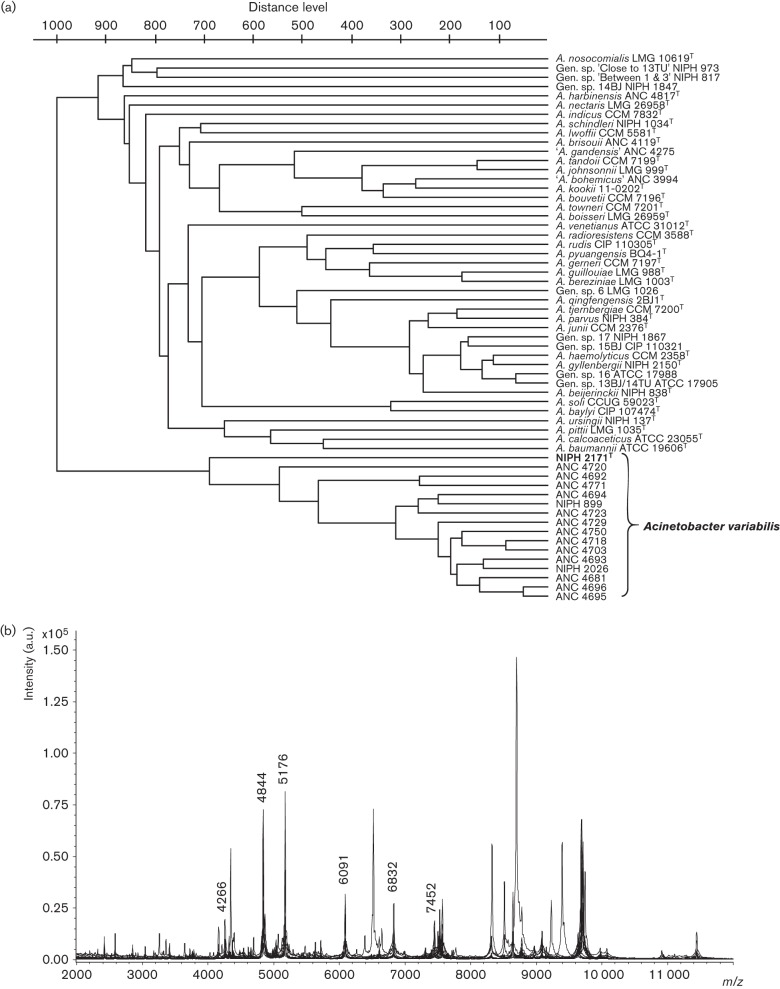

Whole-cell MALDI-TOF MS profiling was performed using a standard extraction protocol based on the extraction with acetonitrile/formic acid/water and alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid used as matrix (Krizova et al., 2014). MALDI-TOF mass spectra measurements were carried out using an UltrafleXtreme instrument (Bruker Daltonics), operated in linear positive mode under control of the FlexControl 3.4 software. Mass spectra were processed using the Flex Analysis version 3.4 and BioTyper version 3.1 software (Bruker Daltonics). The parameters of methods used for calibration, acquisition and evaluation of the obtained mass spectra were as described (Krizova et al., 2014). Based on MALDI-TOF MS analysis, the 16 strains formed a cohesive, although rather heterogeneous, cluster, which was separated from the type/reference strains of the hitherto known species of the genus Acinetobacter (Fig. 2a). All the 16 strains shared six peaks in the range of 4.2–7.5 kDa (Fig. 2b), but none of these peaks was unique for A. variabilis sp. nov. The variability within the spectra of the 16 strains resulted from the presence of intense strain-specific signals, detected mostly within the range of 8.2–9.8 kDa.

Fig. 2.

(a) Dendrogram based on the MALDI-TOF mass spectra of 16 strains of Acinetobacter variabilis sp. nov. and the type/reference strains of other species of the genus Acinetobacter. The dendrogram was constructed using UPGMA. (b) Combined spectra of the strains of A. variabilis sp. nov. with the peaks shared by all the strains indicated by molecular mass.

The in-house metabolic and physiological tests were performed as previously described (Nemec et al., 2009, 2011; Krizova et al., 2014). The assimilation and temperature growth tests were performed in fluid mineral medium supplemented with 0.1 % (w/v) carbon source and brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid), respectively. The cultivation temperature was 30 °C unless indicated otherwise. All tests were performed at least twice in a strictly standardized fashion and repeated when inconsistent results were obtained. The properties of the 16 strains were compared with those of nearly 800 strains deposited in the Acinetobacter collection of the Laboratory of Bacterial Genetics, which represent all species with validly published names and a number of tentative species or taxonomically unique strains. This comparison revealed two characteristic metabolic features of A. variabilis sp. nov. First, each of the 16 strains used a rather limited number of carbon sources; individual strains utilized 4–10 out of 36 different substrates tested (mean, 7.5 substrates). Thus, they could be easily differentiated from more biochemically active species such as those of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–Acinetobacter baumannii complex, Acinetobacter baylyi, Acinetobacter soli, Acinetobacter tandoii, Acinetobacter rudis, Acinetobacter gerneri and Acinetobacter brisouii, and from most species encompassing proteolytic and/or haemolytic strains [Acinetobacter beijerinckii, Acinetobacter gyllenbergii, Acinetobacter haemolyticus, Acinetobacter venetianus, gen. sp. 6 and gen. sp. 13–17 sensu Bouvet & Jeanjean (1989)]. Second, each strain displayed a unique combination of metabolic and physiological features. The name A. variabilis sp. nov. is proposed to reflect this unusual intra-species variability (as well as that of MALDI-TOF mass spectra). A consequence of this variability is the absence of unequivocal diagnostic traits enabling to differentiate A. variabilis sp. nov. from some other relatively inactive species including Acinetobacter indicus, Acinetobacter junii, A. kookii, A. lwoffii, or Acinetobacter towneri. The properties of A. variabilis sp. nov. and phenotypically most similar species are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Phenotypic characteristics of Acinetobacter variabilis sp. nov. and phenotypically most similar species of the genus Acinetobacter.

Species: 1, A. variabilis sp. nov. (n = 16, where n is no. of strains); 2, A. bouvetii (n = 1); 3, A. gandensis (n = 6); 4, A. harbinensis (n = 1); 5, A. indicus (n = 2); 6, A. johnsonii (n = 20); 7, A. junii (n = 14); 8, A. kookii (n = 1); 9, A. lwoffii (n = 16); 10, A. parvus (n = 10); 11, A. radioresistens (n = 12); 12, A. schindleri (n = 23); 13, A. towneri (n = 2); 14, A. ursingii (n = 29). All species with validly published names include the type strain. Results were obtained either in this study or have been published previously (Krizova et al., 2014; Smet et al., 2014). Tests were evaluated after six (assimilation tests), three (haemolytic and gelatinase activities), or two (d-glucose acidification, temperature growth tests) days. All strains grew on acetate, whereas no strains liquefied gelatin or grew on β-alanine, citraconate, d-gluconate, d-glucose, levulinate, trigonelline instead of putrescine. +, All strains positive; −, all strains negative; numbers, percentages of strains giving a positive reaction; d, mostly doubtful reactions; w, mostly weak positive reactions.

| Characteristic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| Growth at: | ||||||||||||||

| 44 °C | 31 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 41 °C | + | − | − | − | + | − | 93 | + | 6 | − | + | + | +w | − |

| 37 °C | + | d | + | − | + | 25w | + | + | + | 90 | + | + | + | + |

| Acidification of d-glucose | 13 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 19 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Haemolysis of sheep blood | − | − | − | − | − | 70w | 50 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Utilization of: | ||||||||||||||

| trans-Aconitate | 6 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 6 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Adipate | 69 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 81 | − | 92 | 30 | − | + |

| 4-Aminobutyrate | 19 | − | − | − | − | + | 86 | + | 88 | − | + | − | − | − |

| l-Arabinose | 19 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| l-Arginine | 19 | − | − | − | − | + | 93 | − | − | − | 83 | − | − | − |

| l-Aspartate | − | − | − | − | − | 95 | 21 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 97w |

| Azelate | 81 | − | − | − | 50 | − | − | − | + | − | + | 64 | − | + |

| Benzoate | 88 | + | + | + | 50 | + | 79 | + | 88 | − | + | 75 | + | 50 |

| 2,3-Butanediol | 81 | − | 33 | − | − | 80 | − | + | 6 | − | + | 32 | 50 | − |

| Citrate (Simmons) | 25 | + | 50 | − | − | 90 | 79 | − | 13 | − | − | 59 | − | + |

| Ethanol | + | + | + | + | + | + | 93 | + | + | + | + | 95 | + | + |

| Gentisate | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 30 | − | − |

| l-Glutamate | 25 | + | 33 | − | 50 | + | + | − | 6 | − | 92 | − | 50 | + |

| Glutarate | 19 | + | 83 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | 95 | − | 97 |

| l-Histidine | − | + | − | − | − | − | 93 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoate | − | − | − | − | − | 30 | − | − | − | − | − | 64 | − | 97 |

| dl-Lactate | 6 | + | + | + | + | + | 93 | + | 89 | − | + | + | + | + |

| l-Leucine | − | − | − | − | − | − | 14 | − | − | − | 92 | − | − | − |

| d-Malate | 13 | − | − | − | − | 15w | 79 | − | 19w | − | − | 95 | 50 | + |

| Malonate | − | − | 17 | + | − | 90 | − | − | 6 | − | + | − | − | − |

| l-Ornithine | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 20 | − | − | − | − |

| Phenylacetate | 75 | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | 69 | − | + | − | − | − |

| l-Phenylalanine | 38 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 92 | − | − | − |

| Putrescine | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 92 | − | − | − |

| d-Ribose | 13 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| l-Tartrate | − | − | − | − | − | 45 | − | − | − | − | − | 18 | − | − |

| Tricarballylate | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 6 | − | − | 25 | − | − |

Description of Acinetobacter variabilis sp. nov.

Acinetobacter variabilis (va.ri.a′bi.lis. L. masc. adj. variabilis variable, referring to the heterogeneous, strain-dependent phenotypic properties of the species).

The phenotypic characteristics correspond to those of the genus (Baumann et al., 1968), i.e. Gram-negative, strictly aerobic, oxidase-negative and catalase-positive coccobacilli typically occurring in pairs, incapable of swimming motility, capable of growing in mineral media with acetate as the sole carbon source and ammonia as the sole source of nitrogen, and incapable of dissimilative denitrification. Positive in the transformation assay (Juni, 1972).

Colonies on tryptic soy agar (Oxoid) after 24 h incubation at 30 °C are 1.0–2.5 mm in diameter, grey–white, slightly opaque, circular, convex and smooth, with entire margins. Growth occurs in brain heart infusion (Oxoid) at temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 41 °C and to a certain extent at 44 °C (about one-third of strains weakly positive). Acid is produced from d-glucose by the minority of strains. Gelatin is not hydrolysed. Haemolysis is not observed on agar media supplemented with sheep erythrocytes, although some strains display a greenish discoloration of the agar. Acetate and ethanol are utilized as sole sources of carbon with growth visible in six (mostly two) days of incubation. No growth occurs on β-alanine, l-aspartate, citraconate, gentisate, d-gluconate, d-glucose, histamine, l-histidine, 4-hydroxybenzoate, l-leucine, levulinate, malonate, l-ornithine, putrescine, l-tartrate, tricarballylate, trigonelline, or tryptamine in 10 days. Various numbers of strains utilize trans-aconitate, adipate, 4-aminobutyrate, l-arabinose, l-arginine, azelate, benzoate, 2,3-butanediol, citrate (Simmons), l-glutamate, glutarate, dl-lactate, d-malate, phenylacetate, l-phenylalanine or d-ribose within 6 days (Table 2).

The type strain is NIPH 2171T ( = CIP 110486T = CCUG 26390T = NIPH 546T = CCM 8555T = Tjernberg & Ursing 151aT), isolated from urine of a human patient in Malmö , Sweden in the 1980s. It was used as the reference strain of DNA group 15 by Tjernberg & Ursing (1989). The type strain (NIPH 2171T) grows weakly at 44 °C and assimilates azelate, benzoate, 2,3-butanediol, d-malate and phenylacetate. It produces whitish colonies 2.0 mm in diameter on tryptic soy agar after 24 h at 30 °C. Strain NIPH 2171T neither produces acid from d-glucose nor utilizes trans-aconitate, 4-aminobutyrate, l-arabinose, l-arginine, citrate (Simmons), l-glutamate, glutarate, dl-lactate, l-phenylalanine or d-ribose. Growth on adipate is visible between the sixth and tenth day of incubation. The fatty acid pattern of this strain was published by Kämpfer (1993). The whole genome sequence of is available from NCBI under accession no. APRS00000000. The GenBank accession nos. for the partial rpoB and 16S rRNA gene sequences of strain NIPH 2171T are EU477119 and KP278590, respectively.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the donors listed in Table 1 for generous provision of strains and Eva Kodytkova (National Institute of Public Health, Prague) for linguistic revision of the manuscript. The authors also thank the Wadsworth Center Applied Genomic Technologies Core for Sanger and next-generation sequencing, and the Wadsworth Center Bacteriology Laboratory for maintaining the novel strains described in this study. The study benefited from the public availability of Acinetobacter genome sequences generated by the Broad Institute Genome Sequencing Platform within the collaborative project (NCBI BioProject no. PRJNA183623). This work was supported by a grant from the Czech Science Foundation (13-26693S) and by MH CZ - DRO [National Institute of Public Health (NIPH) 75010330].

Abbreviations:

- ANIb

average nucleotide identity based on blast

- DDH

DNA–DNA hybridization

- MALDI-TOF MS

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry

References

- Baumann P., Doudoroff M., Stanier R. Y. (1968). A study of the Moraxella group. II. Oxidative-negative species (genus Acinetobacter). J Bacteriol 95, 1520–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvet P. J. M., Grimont P. A. D. (1986). Taxonomy of the genus Acinetobacter with the recognition of Acinetobacter baumannii sp. nov., Acinetobacter haemolyticus sp. nov., Acinetobacter johnsonii sp. nov., and Acinetobacter junii sp. nov. and emended descriptions of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Acinetobacter lwoffii. Int J Syst Bacteriol 36, 228–240. 10.1099/00207713-36-2-228 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvet P. J. M., Jeanjean S. (1989). Delineation of new proteolytic genomic species in the genus Acinetobacter. Res Microbiol 140, 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juni E. (1972). Interspecies transformation of Acinetobacter: genetic evidence for a ubiquitous genus. J Bacteriol 112, 917–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kämpfer P. (1993). Grouping of Acinetobacter genomic species by cellular fatty acid composition. Med Microbiol Lett 2, 394–400. [Google Scholar]

- Krizova L., Maixnerova M., Sedo O., Nemec A. (2014). Acinetobacter bohemicus sp. nov. widespread in natural soil and water ecosystems in the Czech Republic. Syst Appl Microbiol 37, 467–473. 10.1016/j.syapm.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemec A., Dijkshoorn L., Ježek P. (2000). Recognition of two novel phenons of the genus Acinetobacter among non-glucose-acidifying isolates from human specimens. J Clin Microbiol 38, 3937–3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemec A., Musílek M., Maixnerová M., De Baere T., van der Reijden T. J. K., Vaneechoutte M., Dijkshoorn L. (2009). Acinetobacter beijerinckii sp. nov. and Acinetobacter gyllenbergii sp. nov., haemolytic organisms isolated from humans. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 59, 118–124. 10.1099/ijs.0.001230-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemec A., Krizova L., Maixnerova M., van der Reijden T. J. K., Deschaght P., Passet V., Vaneechoutte M., Brisse S., Dijkshoorn L. (2011). Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex with the proposal of Acinetobacter pittii sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 3) and Acinetobacter nosocomialis sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU). Res Microbiol 162, 393–404. 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L., Berçot B., Millemann Y., Bonnin R. A., Pannaux G., Nordmann P. (2012). Carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter spp. in Cattle, France. Emerg Infect Dis 18, 523–525. 10.3201/eid1803.111330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M., Rosselló-Móra R. (2009). Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 19126–19131. 10.1073/pnas.0906412106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smet A., Cools P., Krizova L., Maixnerova M., Sedo O., Haesebrouck F., Kempf M., Nemec A., Vaneechoutte M. (2014). Acinetobacter gandensis sp. nov. isolated from horse and cattle. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64, 4007–4015. 10.1099/ijs.0.068791-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjernberg I., Ursing J. (1989). Clinical strains of Acinetobacter classified by DNA-DNA hybridization. APMIS 97, 595–605. 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1989.tb00449.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchon M., Cury J., Yoon E.-J., Krizova L., Cerqueira G. C., Murphy C., Feldgarden M., Wortman J., Clermont D., et al. (2014). The genomic diversification of the whole Acinetobacter genus: origins, mechanisms, and consequences. Genome Biol Evol 6, 2866–2882. 10.1093/gbe/evu225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Broek P. J., van der Reijden T. J. K., van Strijen E., Helmig-Schurter A. V., Bernards A. T., Dijkshoorn L. (2009). Endemic and epidemic Acinetobacter species in a university hospital: an 8-year survey. J Clin Microbiol 47, 3593–3599. 10.1128/JCM.00967-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]