Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the incidence of remission among patients with intermediate uveitis; to identify factors potentially predictive of remission.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Methods

Involved eyes of patients with primary non-infectious intermediate uveitis at 4 academic ocular inflammation subspecialty practices, followed sufficiently long to meet the remission outcome definition, were studied retrospectively by standardized chart review data. Remission of intermediate uveitis was defined as a lack of inflammatory activity at ≥2 visits spanning ≥90 days in the absence of any corticosteroid or immunosuppressant medications. Factors potentially predictive of intermediate uveitis remission were evaluated using survival analysis.

Results

Among 849 eyes (of 510 patients) with intermediate uveitis followed over 1,934 eye-years, the incidence of intermediate uveitis remission was 8.6/100 eye-years (95% confidence interval (CI), 7.4–10.1). Factors predictive of disease remission included prior pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) (HR (vs. no PPV)=2.39; 95% CI, 1.42–4.00), diagnosis of intermediate uveitis within the last year (vs. diagnosis >5 years ago)=3.82; 95% CI, 1.91–7.63), age ≥45 years (HR (vs. age <45 years)=1.79; 95% CI, 1.03–3.11), female sex (HR=1.61; 95% CI, 1.04–2.49), and Hispanic race/ethnicity (HR (vs. white race)=2.81; 95% CI, 1.23–6.41). Presence/absence of a systemic inflammatory disease, laterality of uveitis, and smoking status were not associated with differential incidence.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that intermediate uveitis is a chronic disease with an overall low rate of remission. Recently diagnosed cases, and older, female and Hispanic cases were more likely to remit. With regards to management, pars plana vitrectomy was associated with increased probability of remission.

INTRODUCTION

Uveitis, as the 5th or 6th leading cause of blindness in Western populations, accounts for a large amount of visual disability in the U.S.,1 striking at a younger age than most of the other leading causes of blindness, and thus leading to more years of potential vision lost per case of blindness than conditions striking at a later age. Intermediate uveitis (IU), as defined by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group, is a subset of uveitis in which the primary site of inflammation is in the vitreous, particularly the anterior vitreous and vitreous overlying the ciliary body and peripheral retina-pars plana complex.2 Clinically, inflammation predominantly affects the vitreous, often forming “snowbanks” and/or “snowballs” in association with vitreous cells and inflammatory debris. A small retrospective cohort study providing population-based natural history data suggests that while the majority of intermediate uveitis patients do relatively well, with 75% maintaining visual acuity of 20/40 or better at ten years, the course can vary widely.3 Possible vision-threatening sequelae of intermediate uveitis include but are not limited to macular edema, epiretinal membrane formation, cataract, retinal neovascularization, vitreous cellular opacification, and retinal detachment.3–5

The probability of remission of intermediate uveitis, and predictive factors for remission, are unclear. Valencic et al. studied 29 patients with unilateral or bilateral intermediate uveitis and found that one-third of patients achieved remission for longer than one year, with a mean time-to-remission of 8.6 years.6 An additional study conducted by Smith et al 1973 reported a remission rate of cyclitis, a term previously used for intermediate uveitis, to be 5% in patients with variable follow-up ranging from 4–26 year follow up.7

With regard to treatment options to induce remission of intermediate uveitis, a “4-step” approach proposed by Kaplan et al. in 1984, suggests a trial of (local/systemic) corticosteroids, followed by peripheral retinal ablation, pars plana vitrectomy, and, finally, immunomodulatory therapy for refractory cases.8 However, this approach has not been universally accepted; with increasing evidence of safety9–11 and effectiveness,11–16 many clinicians are using immunosuppressive therapy at an earlier stage. Remission of ocular inflammatory diseases in general seems to be infrequent with antimetabolite12–14 or cyclosporine therapy,15 but fairly common with alkylating agent therapy.16 However, alkylating agent therapy generally is reserved for very severe cases, because of an apparently increased risk of cancer.9 Therefore, with the treatment approaches typically used, clinicians often are aiming to suppress inflammation in hopes that remission will occur during the period of suppression.

Because remission would be a more desirable outcome than suppression, we evaluated the incidence of remission in a large retrospective cohort of patients with intermediate uveitis, and evaluated potentially modifiable and non-modifiable factors potentially predictive of remission.

METHODS

Study Population

Patients with a diagnosis of intermediate uveitis were identified from the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Disease (SITE) Cohort Study, a retrospective cohort study of non-infectious ocular inflammatory disease patients at US tertiary ocular inflammation subspecialty centers, the methods of which have been described previously.17 The institutional review boards of the University of Pennsylvania (IRB#1), the Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary (Human Subjects Committee), the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (JHM-IRB 3), the National Eye Institute (NEI/IRB) and Oregon Health & Sciences University (OHSU Institutional Review Board) approved the study, including waiver of informed consent for this chart review study which involved no contact with the human subjects. The study was conducted adhering to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was compliant with all relevant laws.

Intermediate uveitis had been identified in charts in a manner very similar to that adopted Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) group standards,2 as the leaders of the SUN Group were leading clinicians in the SITE Cohort Study. Those patients identified in medical records as having intermediate uveitis but who also had iris synechiae and/or a formal secondary diagnosis of anterior uveitis or some other inflammatory syndrome were excluded, in order to limit the population to classic intermediate uveitis, the population which makes up the study cohort reported here. This population includes ‘pars planitis’ as well as other forms of intermediate uveitis, as described in the SUN consensus manuscript,2 whether or not a systemic disease was associated.

Data Collection

Data were obtained and entered in a computerized database entry system (Microsoft Access, Redmond, WA USA) with built-in quality assurance measures allowing for correction of errors in real time. Data used for the current analysis included demographic data, the presence of systemic diseases, the presence of HLA-B27 and HLA-A29 haplotypes (when available), time between intermediate uveitis diagnosis and presentation, inflammatory findings at every visit and treatments used throughout follow-up. Collected patient demographic data included age, gender, race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic, “Other”) and smoking status. The systemic inflammatory diseases evaluated are summarized in the Table. Use of peripheral ablation (cryotherapy or laser), and pars plana vitrectomy were noted.

Table 1.

Factors potentially association with remission of intermediate uveitis*

| Characteristics | Characteristic Value | Total Eyes | Remissions Observed | Eye-Years | Incidence rate (95% CI) | Crude HR of Remission (95% CI) | Adjusted HR of Remission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of eyes | 849 | 167 | 1934.4 | .086 (.074 – .10) | |||

| Age | Age<18 | 154 | 34 | 419.31 | .081 (.056 – .11) | 1.18(0.68 – 2.04) | 0.95(0.53 – 1.70) |

| 18≤Age<30 | 211 | 35 | 550.85 | .064 (.044 – .088) | 0.96(0.54 – 1.68) | 0.82(0.46 – 1.46) | |

| 30≤Age<45 | 271 | 43 | 596.42 | .0721 (.052 – .097) | Reference group | Reference group | |

| Age≥45 | 213 | 55 | 367.79 | .15 (.11– .19) | 2.00(1.21 – 3.30) | 1.79(1.03 – 3.11) | |

| Gender | Male | 315 | 44 | 790.67 | .056 (.040 – .075) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 534 | 123 | 1143.7 | .11 (.089 – .13) | 1.82(1.18 – 2.81) | 1.61(1.04 – 2.49) | |

| Race | White | 731 | 151 | 1665.0 | .0907 (.077 – .11) | Reference group | Reference group |

| Black | 43 | 5 | 138.59 | .036 (.012 – .084) | 0.46(0.13 – 1.61) | 0.53(0.14 – 2.04) | |

| Hispanic | 34 | 9 | 31.14 | .29 (.13 – .55) | 2.39(0.96 – 5.95) | 2.81(1.23 – 6.41) | |

| Other | 41 | 2 | 99.64 | .020 (.0024 – .073) | 0.24(0.05 – 1.07) | 0.26(0.06 – 1.19) | |

| Any systemic disease** | Yes | 94 | 14 | 266.60 | .053 (.029 – .088) | 0.62(0.30 – 1.24) | 0.59(0.29 – 1.22) |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Yes | 8 | 5 | 29.61 | .17 (.055 – .39) | 2.25(0.70 – 7.22) | 1.50(0.39 – 5.83) |

| Sarcoidosis | Yes | 43 | 9 | 116.21 | .077 (.035 – .15) | 0.94(0.40 – 2.21) | 0.63(0.23 – 1.70) |

| Multiple sclerosis | Yes | 40 | 7 | 84.50 | .083 (.033 – .17) | 0.89(0.42 – 1.90) | 0.73(0.30 – 1.73) |

| Smoking status | Never Smoker | 425 | 97 | 1001.6 | .097 (.079 – .12) | Reference group | Reference group |

| Former Smoker | 70 | 24 | 176.14 | .14 (.087 – .20) | 1.37(0.79 – 2.40) | 0.97(0.54 – 1.76) | |

| Current Smoker | 216 | 32 | 443.45 | .072 (.049 – .10) | 0.71(0.43 – 1.16) | 0.79(0.46 – 1.35) | |

| Unknown | 138 | 14 | 313.19 | .045 (.024 – .075) | 0.43(0.21 – 0.87) | 0.41(0.20 – 0.86) | |

| Number of years since diagnosis of uveitis | ≤ 1 year | 415 | 42 | 137.45 | .31(.22 – .41) | 3.81(1.94 – 7.48) | 3.82(1.91 – 7.63) |

| >1 to 5 years | 264 | 70 | 715.55 | .098 (.076 – .12) | 1.55(0.91 – 2.65) | 1.50(0.87 – 2.60) | |

| over 5 years | 170 | 55 | 1081.4 | .051 (.038 – .066) | Reference group | Reference group | |

| Bilateral uveitis | Yes | 771 | 150 | 1774.7 | .085 (.072 – .099) | 0.82(0.48 – 1.39) | 0.73(0.43 – 1.23) |

| Snowballs at enrollment | Yes | 234 | 40 | 427.89 | .094 (.067 – .13) | 1.04(0.69 – 1.56) | 0.98(0.66 – 1.46) |

| Peripheral ablation*** | Yes | 44 | 9 | 83.23 | .11 (.049 – .21) | 1.31(0.67 – 2.55) | 1.71(0.84 – 3.45) |

| Pars plana vitrectomy | Yes | 81 | 23 | 123.64 | .19 (.12 – .28) | 2.84(1.76 – 4.58) | 2.39(1.42 – 4.00) |

CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio; adjusted values are adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, presence of snowballs at the initial visit, the number of years since uveitis diagnosis, and whether or not peripheral ablation or pars plana vitrectomy were performed.

There were no cases of reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, polyarteritis nodosum, Wegener’s, Takayasu, scleroderma, Sjogren’s, dermatomyositis, polymyositis, relapsing polychrondritis, Cogan’s, or familial systemic granulomatosis. There was no association observed between intermediate uveitis remission and spondylarthropathy (i.e. ankylosing spondylitis), Behcet Disease, systemic lupus erythematosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, HLA-B27+ status, or HLA-A29+ status; however available power often was limited to detect such associations if they in fact exist.

Peripheral retina/pars plana ablation using either cryotherapy or scatter photocoagulation.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was remission of intermediate uveitis among eyes (as opposed to patients). Intermediate uveitis remission was defined as the complete absence of inflammatory signs in an eye across all visits spanning a period of at least 90 days, in the absence of any ocular or systemic anti-inflammatory treatment.2

Statistical Analyses

Follow-up time was the sum of the time eyes at “risk” of remission were followed (until occurrence of remission, or cessation of follow-up due to censoring or the end of the study). An eye-year is 365.25 such days. The incidence of intermediate uveitis remission was calculated as the number of events per eye-year among those still under observation who had not yet had remission at presentation; 95% confidence intervals assumed a Poisson distribution. Factors potentially predictive of remission were evaluated using survival analysis. Cox regression (with 95% confidence interval bounds indicated as subscripts before and after the estimates) was used to generate crude and adjusted hazard ratios for each factor, with final models selected based on associations observed in the crude analyses, and the factors of specific scientific interest. Final multiple regression models adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, presence of snowballs at the initial visit, the number of years since uveitis diagnosis, and whether or not peripheral ablation or pars plana vitrectomy were performed. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed for selected variables to display the relationship with incidence of uveitis remission as a function of time. Analyses were performed using Stata 11 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) and SAS v9.1 (SAS Corporation, Cary, NC) software.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 849 eyes (of 510 patients) with intermediate uveitis meeting eligibility criteria. These had been followed over 1,934 eye-years at the participating centers. The majority of eyes belonged to females (63%) and persons of white race (86%), and half to known non-smokers (50%). All age groups were represented; 18% were less than 18 years old, 25% were between 18 and 30 years of age, 32% were between 30 and 45 years of age, and 25% were 45 years of age or older. The majority (91%, 82% of patients) experienced bilateral intermediate uveitis at some point during their clinical course. There were 43 eyes of patients with sarcoidosis (5.1%), and 40 eyes of patients with multiple sclerosis (4.7%).

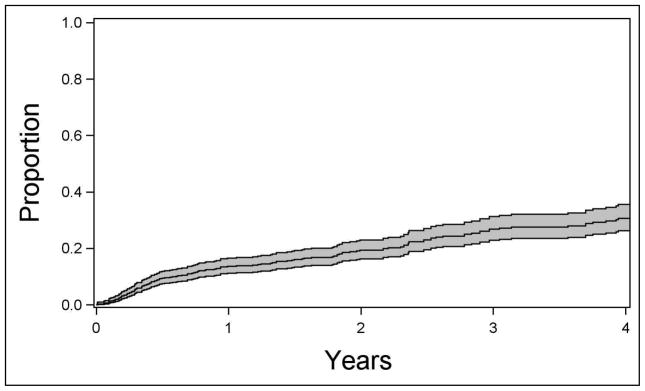

A total of 167 remissions of disease activity, spanning at least 90 days in the absence of any anti-inflammatory medication, were observed. The calculated incidence rate for intermediate uveitis remission was 8.6/100 eye-years (95% confidence interval (CI), 7.4–10.1/100 eye-years; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of the proportion of eyes with intermediate uveitis achieving remission over time, with 95% confidence interval bands.

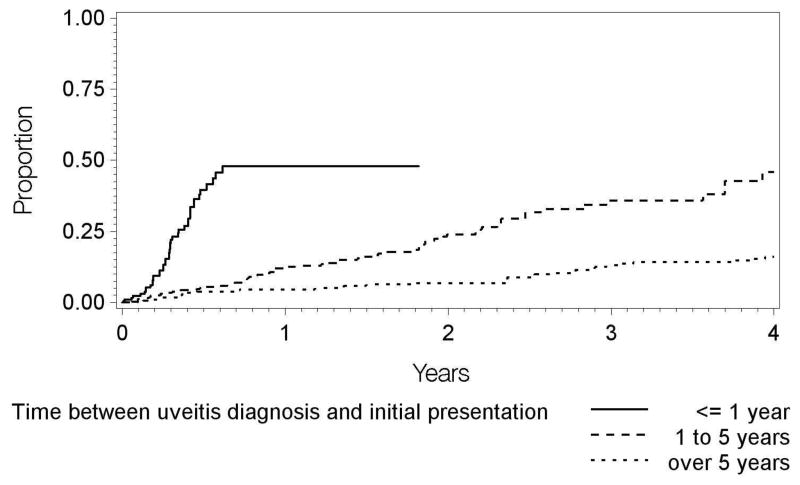

The relationship of potentially predictive factors to intermediate uveitis remission is given in Table 1. Demographic characteristics associated with greater incidence of remission included age 45 years or greater (incidence=15.0 per 100 eye-years, adjusted HR (vs. 30≤Age<45 years) = 1.79; 95% CI, 1.03 – 3.11), female sex (incidence=10.8 per 100 eye-years, adjusted HR (vs. males) = 1.61; 95% CI, 1.04 – 2.49), and Hispanic race/ethnicity (incidence=28.9 per 100 eye-years, adjusted HR (vs. white race/ethnicity) = 2.81; 95% CI, 1.23 – 6.41). Few cases meeting eligibility criteria were observed in Black or other races/ethnicities. Diagnosis of intermediate uveitis within the last year also was associated with a greater incidence of remission (incidence=30.6 per 100 eye-years, adjusted HR = 3.82; 95% CI, 1.91 – 7.63) with respect to longstanding cases diagnosed more than five years previously. The incidence of remission was 10/100 eye-years for cases diagnosed with intermediate uveitis one to five years prior to presentation, and 5/100 eye-years for cases diagnosed over five years previously. Associated systemic diseases were not associated with significant differences in the incidence of remission, nor were bilaterality of uveitis or the presence or absence of vitreous snowballs at the initial examination.

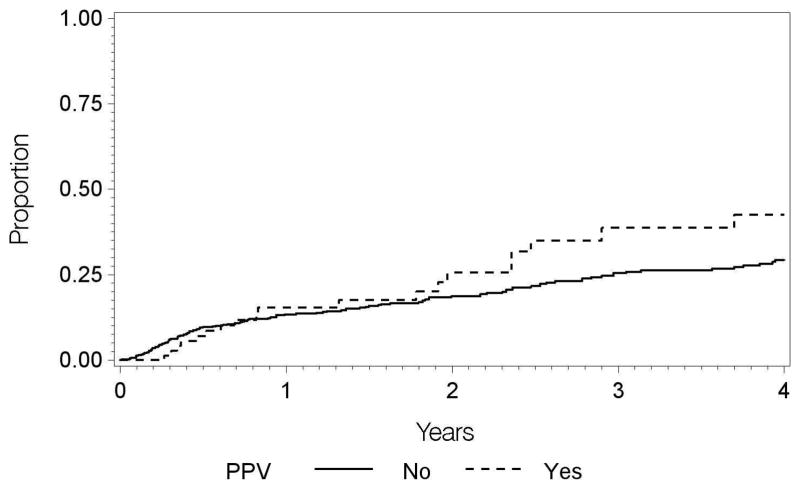

Regarding modifiable risk factors, a history of pars plana vitrectomy was associated with an increased incidence of remission; among the 81 cases (9.5%) which (for any reason) had undergone pars plana vitrectomy, the incidence of remission was 18.6 per 100 eye-years (adjusted HR (vs. no PPV) = 2.39; 95% CI, 1.42 – 4.00). Peripheral ablation tended to be associated with a higher incidence of intermediate uveitis remission, however the results were not statistically significant in terms of crude or adjusted analyses with 44 eyes treated (adjusted HR 1.82; 95% CI, 0.88–3.78). Smoking status was not associated with differences in the incidence of intermediate uveitis remission..

Sensitivity analyses were conducted in which cases with minimal activity (e.g., “trace” or 0.5+ cells), as being effectively in remission found similar results.

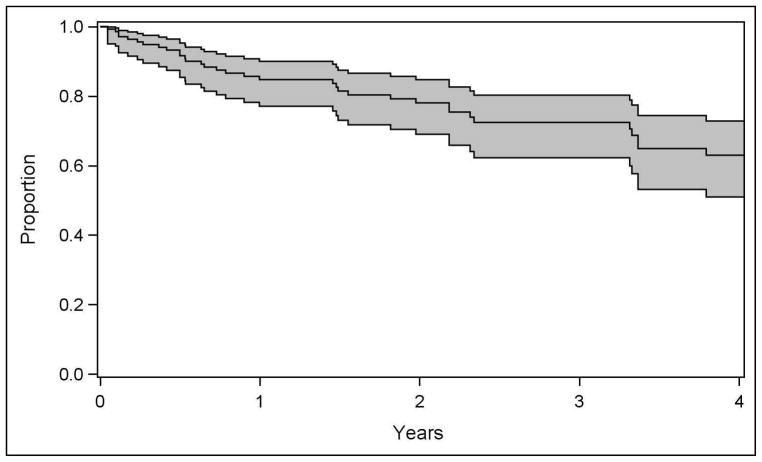

Among the 167 eyes meeting criteria for remission, 27 eyes did not have sufficient follow up time after remission to be at risk of relapse. Of the 140 eyes that did, 37 eyes experienced a relapse of intermediate uveitis. With a total of 379.8 eye-years of follow up of these eyes, the incidence of relapse after remission (defined as two or more visits with activity spanning 90 days) was 9.7 per 100 eye-years (95% CI: 6.9–13/100 eye-years). An analysis of the same group of factors described in Table 1—adjusting for age, sex, race, and smoking status—identified diagnosis with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (three of five uveitic eyes relapsed, adjusted HR=2.5, 95% CI: 1.3–4.8; absolute recurrence incidence of 26/100 eye-years) as the only known factor clearly associated with higher (or lower) risk of relapse. Smokers did not have a significantly different risk of relapse with respect to nonsmokers (adjusted HR=2.08, 95% CI; 0.80–4.08). Prior pars plana vitrectomy (five of 26 uveitic eyes relapsed, HR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.24–1.66) and peripheral ablation (one of eight uveitic eyes relapsed, HR=0.30, 95% CI: 0.03–2.90) were not associated with significant differences in the risk of relapse after meeting criteria of remission but tended in a favorable direction. In general, statistical power was limited to detect associations due to the small number of relapses observed.

DISCUSSION

The results of our large cohort of patients managed at tertiary uveitis centers indicate that intermediate uveitis is a chronic disease with a low incidence of remission, on the order of approximately 8.6 per 100 eye-years. While the two earlier small cohort studies of Vidovic-Valentincic et al6 and of Smith et al7 used different methods to summarize the incidence of remission, both were in agreement in finding a low incidence of remission.

Vidovic-Valentincic et al6 identified age<20 years and lack of associated systemic disease as factors associated with higher crude remission. Regarding age, we observed a different pattern in which the incidence of remission was highest in the oldest age group age 45 years or older, and did not tend to be lower in young cases, after adjusting for other potentially confounding factors. We also found that females were more likely than males and Hispanics than Whites to experience remission. The number of cases in other races/ethnicities was too small to evaluate remission incidence with reasonable power.

That a recent diagnosis of intermediate uveitis was associated with a greater incidence of remission seems intuitively reasonable, as many cases destined for remission might remit in the first few years, whereas those persisting for longer periods of time before referral to a tertiary center would be those which had not remitted in the first few years. Our tertiary centers were university-affiliated, and primarily receive referrals on the basis of cases’ complexity, but also receive patients at a relatively early point in their clinical course should they initially report to the university facility for care. The latter cases likely are generally less severe cases, and also would have received the benefit of uveitis specialty care at an earlier stage in their clinical course, each of which also could explain part of this observed association.

Regarding potentially modifiable factors, the potential beneficial role of pars plana vitrectomy in the management of non-infectious intermediate uveitis, suggested by Diamond and Kaplan in 1978,18 has not previously been tested in a well-powered, randomized controlled trial. Our retrospective, observational results support the view that vitrectomy can induce remission of intermediate uveitis, in that prior pars plana vitrectomy represented the only therapeutic factor significantly related to increased incidence of intermediate uveitis remission in this study. However, although the incidence of remission was about 2.5-fold higher following vitrectomy, not all cases responded. Our study was unable to assess whether cases that did not remit experienced a reduction in disease severity on average. Wiechens et al. in an uncontrolled study observed a regression of cystoid macular edema in 59% of intermediate uveitis cases after vitrectomy, although the authors speculated that removal of vitreous adhesions at the macula and detachment of the posterior hyaloid plays a role in CME regression rather than invoking an effect on inflammation.19 Immunologic-based theories exist regarding the potential anti-inflammatory role of vitrectomy in intermediate uveitis.20 Not only does vitrectomy provide a method to mechanically decrease the current inflammatory load in the vitreous,21 but it also potentially increases the penetration of anti-inflammatory mediators and medication through the uveal tissue.22 Elimination of a phenomenon called vitreous cavity-associated immune deviation (VCAID), via the surgical removal of hyalocytes (the antigen-presenting cells of the vitreous), as well as extension of anterior chamber acquired immune deviation (ACAID) to the vitreous cavity, may represent advantages of pars plana vitrectomy in reducing inflammation in intermediate uveitis-affected eyes.23,24 On the other hand, vitrectomy eliminates the potential for the vitreous to serve as a depot prolonging the duration of effect of injected pharmaceuticals, a potential disadvantage of the approach.

In our retrospective, observational study, vitrectomy likely was performed for indications such as epiretinal membrane, vitreous hemorrhage, macular pucker, cyclitic membranes causing hypotony, retinal detachment, and media opacity25–32 in many instances, rather than specifically to induce remission of uveitis. It is possible that in this cohort, vitrectomy tended to be performed in more severe cases that had these complications of uveitis, in which case the therapeutic benefit thereof might be underestimated. Given the potential risks of vitrectomy, our results do not provide a strong rationale for widespread use of this therapy absent clinical trial verification of safety and effecacy, especially for cases with recent onset which might remit on their own, although for selected cases (especially those with additional indications for vitrectomy) it may be a useful therapeutic approach. Prospective study of vitrectomy for induction of uveitis remission in a clinical trial, including assessment of potential benefits on disease severity and the incidence of uveitic and surgical complications, would be valuable to better understand its potential value as a therapeutic approach.

Peripheral ablation involves either laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy treatment of the peripheral retina. Previously reported benefits of this treatment include decreases in retinal neovascularization at the vitreous base, vitritis, cystoid macular edema, and/or the need for corticosteroids.3,33 Our study did not find a statistically significant increase in remission following peripheral ablation (HR 1.71; 95% CI, 0.84 – 3.45), although the range of plausible hazard ratios is broad with the available statistical power, and includes values that would correspond to a substantial effect size.

In a population-based study, evaluating 46 eyes of 25 patients in Olmsted County, Minnesota, the proportion of smokers and of multiple sclerosis patients among otherwise idiopathic intermediate uveitis patients was higher than in the general population.3 suggesting smoking and multiple sclerosis as factors possibly involved in or associated with the etiologic mechanism of intermediate uveitis. Smoking also has been suggested as a risk factor for uveitic macular edema in intermediate uveitis cases.34 Nevertheless, regarding remission of intermediate uveitis, our results did not suggest differences in the incidence of remission by smoking status nor with multiple sclerosis or other systemic inflammatory diseases, whether assessed individually or in aggregate. As mentioned previously, multiple sclerosis was not an associated factor either.

Recurrence of intermediate uveitis after remission occurred at a low rate as well. Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis was associated with about a 2.5-fold higher incidence of relapse. This group had tended to have a higher incidence of remission, although not to a statistically significant degree. None of the other known factors were associated with significant differences in the risk of relapse, although statistical power was insufficient to exclude small to moderate associations.

The strengths of this study include its large sample of intermediate uveitis cases, with correspondingly favorable statistical power for many variables. While all patient charts underwent a standardized review process by expert reviewers, the study is limited by its retrospective nature. For instance, if those individuals no longer following up at the participating centers experienced a higher rate of disease remission, which is possible given that less severe cases may be less likely to make ongoing use of tertiary care, then our estimated remission rate would somewhat underestimate the true value. Likewise, enrolled patients were those seen at tertiary ocular inflammation centers, which might represent the most severe intermediate uveitis presentations, which also would contribute to underestimation of the incidence of remission for the general population of intermediate uveitis patients. However, our results still should be generalizable to the experience of tertiary centers, and it is likely that the qualitative interpretation of the remission rate as low still would be correct. Regarding risk factor associations, unless the probability of remission in relation to the potential predictive factors studied differs greatly between tertiary and other centers or between patients following up vs. those not following up (which seems unlikely), our results regarding the impact of potential predictive factors on remission incidence should be generalizable. We were limited in our ability to assess the effect of corticosteroid and/or immunosuppression with regards to the incidence of remission in this study since use thereof was defined as indicating a case not in remission, following SUN guidelines.2

In summary, the results of this study suggest that most patients with intermediate uveitis will have ongoing inflammation for many years, during which time clinical management will be required. The results suggest the possibility that surgical intervention might be valuable in inducing remission, particularly those cases wherein vitrectomy surgery is indicated to address some other issue. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the extent of benefit vs. the extent of risk would be valuable to characterize the potential value of this intervention. Given the apparently greater chance of remission in the early years following intermediate uveitis diagnosis, surgical intervention seems relatively less supported in this group. While the visual prognosis of intermediate uveitis is good for most patients3 despite a chronic course for most, better remission-inducing treatments are needed for this disease.

Figure 2.

Incidence of remission of intermediate uveitis over time by length of time between uveitis diagnosis and initial presentation.

Figure 3.

Incidence of remission of intermediate uveitis over time among cases which did and did not receive pars plana vitrectomy (PPV).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of the proportion of cases experiencing relapse of intermediate uveitis over time, beginning follow-up from the point where remission was observed, with 95% confidence interval bands

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Supported primarily by National Eye Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA) Grant EY014943 (Dr. Kempen). Additional support was provided by Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY, USA), the Paul and Evanina Mackall Foundation (New York, NY, USA) and the Lois Pope Life Foundation (New York, NY, USA). During the course of the study, Dr. Kempen was a Research to Prevent Blindness James S. Adams Special Scholar Award recipient, Dr. Thorne was a Research to Prevent Blindness Harrington Special Scholar Award recipient, and Drs. Jabs and Rosenbaum were Research to Prevent Blindness Senior Scientific Investigator Award recipients. Dr. Suhler receives support from the Veteran’s Affairs Administration (Washington, DC, USA). Dr. Levy-Clarke was previously supported by and Drs. Nussenblatt and Sen continue to be supported by intramural funds of the National Eye Institute. The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Biography

Dr. John H. Kempen is Professor of Ophthalmology and Epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. His research evaluates treatment for ocular inflammatory and infectious diseases. He is Chairman of the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases (SITE) Cohort Study and Vice-Chairman of the Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) Trial Network. He is President and Co-Founder of the eyecare organization Sight for Souls, developing self-sustaining comprehensive eye institutes in less-developed countries.

Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases (SITE) Research Group Credit Roster

University of Pennsylvania/Scheie Eye Institute

John H. Kempen, MD, PhD (Principal Investigator, Penn Center Director)

Marshall M. Joffe, MD, PhD (Statistical Methodologist)

Kurt A. Dreger, BS (Database Construction and Management)

Tonetta D. Fitzgerald, BA, COA, CCRC (Project Coordinator)

Craig W. Newcomb, MS (Biostatistician)

Maxwell Pistilli, MS (Biostatistician)

Srishti Kothari, MBBS, DOMS, DNB (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Naira Khacharyan, MD, MPH, DrPH (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Former Members

Pichaporn Artornsombudh, MD (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Asaf Hanish, MPH (Biostatistical Programmer)

Abhishek Payal, MBBS, MPH (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Sapna S. Gangaputra, MBBS, MPH (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Johns Hopkins University/Wilmer Eye Institute

Jennifer E. Thorne, MD, PhD (Center Director, 2007-present)

Hosne Begum, MBBS, MPH (Study Coordinator)

Kurt A. Dreger, BS (Database Construction and Management)

Former Members

Ebenezer Daniel, MBBS, MPH, PhD (Post-doctoral Fellow)

James P. Dunn, MD (Major Clinician)

Sapna S. Gangaputra, MBBS, MPH (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Douglas A. Jabs, MD, MBA (Clinic Founder, Former Clinic Director)

Abhishek Payal, MBBS, MPH (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Mercy Medical Center, Baltimore

Kathy J. Helzlsouer, MD, MHS (Cancer Epidemiologist)

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Douglas A. Jabs, MD, MBA (Founder of JHU Clinic, JHU Clinic Director 2005–2007)

Massachusetts Eye Research & Surgery Institution/Ocular Immunology &Uveitis Foundation

C. Stephen Foster, MD, FACS, FACR (Center Director and Founder, and Director and Founder of previous Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary Center, 2004–2005)

Srishti Kothari, MBBS, DOMS, DNB (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Naira Khacharyan, MD, MPH, DrPH (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Former Members

Pichaporn Artornsombudh, MD (Post-doctoral Fellow)

R. Oktay Kaçmaz, MD, MPH (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Abhishek Payal, MBBS, MPH (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Siddharth S. Pujari, MBBS, MPH (Post-doctoral Fellow)

National Eye Institute, Laboratory of Immunology

H. Nida Sen, MD, MS (NEI Center Director)

Robert B. Nussenblatt, MD, MPH (Center Founder and Co-Director)

Former Members

Grace A. Levy-Clarke, MD (Former Center Director)

Sapna S. Gangaputra, MBBS, MPH (Post-doctoral Fellow)

Oregon Health & Sciences University/Casey Eye Institute

Eric B. Suhler, MD, MPH (Center Director)

James T. Rosenbaum, MD, FACR (Center Founder and Co-Director)

Teresa Liesegang, COT, CRC (Project Coordinator)

University of Pittsburgh

Jeanine Buchanich, PhD (Epidemiologist)

Terri L. Washington (Project Coordinator)

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Kempen has served as a consultant for AbbVie (North Chicago, IL, USA), Alcon (Fort Worth, TX, USA), Allergan (Dublin, Ireland), Can-Fite (Petah-Tikva, Israel), Clearside (Alpharetta, GA, USA), Lux Biosciences (Jersey City, NJ, USA), Roche (Basel, Switzerland), and Xoma (Berkeley, CA, USA), and is a grant recipient from EyeGate (Waltham, MA, USA). Dr. Suhler has served as a consultant for Xoma, Santen (Osaka, Japan), and AbbVie, and has been a grant recipient from AbbVie, Xoma, and Bristol-Myers Squibb (New York, NY, USA). Dr. Thorne has served as a consultant for AbbVie and Xoma. Dr. Foster has served as a consultant for Aldeyra (Lexington, MA, USA), Bausch & Lomb Surgical (Rochester, NY, USA), EyeGate, Novartis (Basel, Switzerland), pSivida (Watertown, MA, USA), and Xoma; has served as a paid speaker for Alcon and Allergan, and has grants or grants pending from Alcon, Aldeyra, Bausch & Lomb, Clearside Biomedical, Dompe (Milan, Italy), Icon (Dublin, Ireland), Novartis, Santen, Xoma, Aciont (Salt Lake City, UT, USA) and pSivida. Dr. Jabs has served as a consultant to Santen and AGTC (Covina, CA, USA). Dr. Kaçmaz is employed by Allergan. Drs. Gewaily, Nussenblatt, Rosenbaum, Sen, and Payal, Mr. Newcomb, Ms. Liesegang, and Ms. Fitzgerald report no financial disclosures.

Online Material: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nussenblatt RB. The natural history of uveitis. Int Ophthalmol. 1990;14(5–6):303–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00163549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(3):509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donaldson MJ, Pulido JS, Herman DC, Diehl N, Hodge D. Pars planitis: a 20-year study of incidence, clinical features, and outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007 Dec;144(6):812–817. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raja SC, Jabs DA, Dunn JP, et al. Ophthalmology. Pars planitis: clinical features and class II HLA associations. Ophthalmology. 1999 Mar;106(3):594–9. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malinowski SM, Pulido JS, Folk JC. Long-term visual outcome and complications associated with pars planitis. Ophthalmology. 1993 Jun;100(6):818–24. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31567-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vidovic-Valentincic N, Kraut A, Hawlina M, Stunf S, Rothova A. Intermediate uveitis: long-term course and visual outcome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(4):477–80. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.149039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith RE, Godfrey WA, Kimura SJ. Chronic cyclitis. I. Course and visual prognosis. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1973;77(6):OP760–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan HJ. Intermediate Uveitis (Pars Planitis, Chronic Cyclitis)- A Four Step Approach to Treatment. In: Saari KM, editor. Uveitis Update. Amsterdam: Exerpta Medica; 1984. pp. 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kempen JH, Gangaputra S, Daniel E, et al. Long-term risk of malignancy among patients treated with immunosuppressive agents for ocular inflammation: A critical assessment of the evidence. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(6):802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kempen JH, Daniel E, Dunn JP, et al. Overall and cancer related mortality among patients with ocular inflammation treated with immunosuppressive drugs: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b2480. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kempen JH, Altaweel MM, Holbrook JT, et al. Randomized comparison of systemic anti-inflammatory therapy versus fluocinolone acetonide implant for intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis: the multicenter uveitis steroid treatment trial. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(10):1916–1926. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasadhika S, Kempen JH, Newcomb CW, et al. Azathioprine for Ocular Inflammatory Diseases. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(4):500–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangaputra S, Newcomb CW, Liesegang TL, et al. Methotrexate for ocular inflammatory diseases. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11):2188–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniel E, Thorne JE, Newcomb CW, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil for ocular inflammatory diseases. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(3):423–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kacmaz RO, Kempen JH, Newcomb C, et al. Cyclosporine for Ocular Inflammatory Diseases. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(3):576–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pujari SS, Kempen JH, Newcomb CW, et al. Cyclophosphamide for Ocular Inflammatory Diseases. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(2):356–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kempen JH, Daniel E, Gangaputra S, et al. Methods for identifying long-term adverse effects of treatment in patients with eye diseases: the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases (SITE) Cohort Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15(1):47–55. doi: 10.1080/09286580701585892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diamond JG, Kaplan HJ. Lensectomy and vitrectomy for complicated cataract secondary to uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96(10):1798–1804. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060310002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiechens B, Nölle B, Reichelt JA. Pars-plana vitrectomy in cystoid macular edema associated with intermediate uveitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;239(7):474–81. doi: 10.1007/s004170100254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez VL, Papaliodis GN, Chu D, Anzaar F, Christen W, Foster CS. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 in the vitreous fluid of patients with pars planitis and posterior uveitis: the Massachusetts eye & ear experience and review of previous studies. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2004;12(3):193–201. doi: 10.1080/092739490500282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn JK, Chung H, Yu HG. Vitrectomy for persistent panuveitis in Behcet’s disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005;13:447–53. doi: 10.1080/09273940591004232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Gelder RN, Kaplan HJ. Diagnostic and therapeutic vitrectomy for uveitis. In: Ryan SJ, editor. Retina. 3. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2001. pp. 2264–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonoda KH, Sakamoto T, Qiao H, et al. The analysis of systemic tolerance elicited by antigen inoculation into the vitreous cavity: vitreous cavity-associated immune deviation. Immunology. 2005;116(3):390–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakamoto T, Ishibashi T. Hyalocytes: essential cells of the vitreous cavity in vitreoretinal pathophysiology? Retina. 2011;31(2):222–8. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181facfa9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker M, Davis J. Vitrectomy in the treatment of uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(6):1096–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Androudi S, Ahmed M, Fiore T, Brazitikos P, Foster CS. Combined pars plana vitrectomy and phacoemulsification to restore visual acuity in patients with chronic uveitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31(3):472–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tranos P, Scott R, Zambarakji H, Ayliffe W, Pavesio C, Charteris DG. The effect of pars plana vitrectomy on cystoid macular oedema associated with chronic uveitis: a randomised, controlled pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006 Sep;90(9):1107–10. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.092965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quinones K, Choi JY, Yilmaz T, Kafkala C, Letko E, Foster CS. Pars plana vitrectomy versus immunomodulatory therapy for intermediate uveitis: a prospective, randomized pilot study. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18(5):411–7. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2010.501132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heiligenhaus A, Bornfeld N, Wessing A. Long-term results of pars plana vitrectomy in the management of intermediate uveitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1996;7(3):77–9. doi: 10.1097/00055735-199606000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dev S, Mieler WF, Pulido JS, Mittra RA. Visual outcomes after pars plana vitrectomy for epiretinal membranes associated with pars planitis. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(6):1086–90. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potter MJ, Myckatyn SO, Maberley AL, Lee AS. Vitrectomy for pars planitis complicated by vitreous hemorrhage: visual outcome and long-term follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131(4):514–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00844-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Svozilkova P, Heissigerova J, Brichova M, Kalvodova B, Dvorak J, Rihova E. The role of pars plana vitrectomy in the diagnosis and treatment of uveitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(1):89–97. doi: 10.5301/ejo.2010.4040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devenyi RG, Mieler WF, Lambrou FH, Will BR, Aaberg TM. Cryopexy of the vitreous base in the management of peripheral uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106(2):135–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90824-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thorne JE, Daniel E, Jabs DA, Kedhar SR, Peters GB, Dunn JP. Smoking as a risk factor for cystoid macular edema complicating intermediate uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(5):841–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]