Abstract

The role of oxidative stress and leukocyte activation has not been elucidated in developing systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in heart failure (HF) patients after continuous-flow left ventricular assist device (CF-LVAD) implantation. The objective of this study was to investigate the change of plasma redox status and leukocyte activation in CF-LVAD implanted HF patients with or without systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). We recruited 31 CF-LVAD implanted HF patients (16 SIRS and 15 Non-SIRS) and 11 healthy volunteers as the control. Pre and post implant blood samples were collected from the HF patients. Plasma levels of oxidized low density lipoprotein (oxLDL), malondialdehyde (MDA), total antioxidant capacity (TAC), superoxide dismutase (SOD) in erythrocyte, myeloperoxidase (MPO) and polymorphonuclear elastase (PMN-elastase) were measured. The HF patients had preexisting condition of oxidative stress than healthy controls as evident from the higher oxLDL and MDA levels as well as depleted SOD and TAC. Leukocyte activation in terms of higher plasma MPO and PMN-elastase were also prominent in HF patients than control. Persistent oxidative stress and reduced antioxidant status were found more belligerent in HF patients with SIRS after the implantation of CF-LVAD when compared to Non-SIRS patients. Similar to oxidative stress, the activation of blood leukocyte were significantly highlighted in SIRS patients after implantation compared to Non-SIRS. We identified that the plasma redox status and leukocyte activation became more prominent in CF-LVAD implanted HF patients who developed SIRS. Our findings suggest that plasma biomarkers of oxidative stress and leukocyte activation may be associated with the development of SIRS after CF-LVAD implant surgery.

Keywords: Heart failure, left ventricular assist device, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, oxidative stress, leukocyte activation

Introduction

Mechanical circulatory support therapy based on continuous-flow left ventricular assist device (CFLVAD) has evolved into a standard therapy for patients with advanced heart failure (HF), either as a destination therapy or a bridge to cardiac transplantation or a bridge to myocardial recovery [1]. Despite demonstrating significant improvements in survival with CF-LVAD when compared to older, pulsatile devices; systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), major infections, renal dysfunction, nonsurgical bleeding, transient ischemic attack or stroke, respiratory failure and right ventricular failure continue to be the frequently reported complications [2-5].

SIRS is a whole-body inflammation that still remains a major clinical problem, despite improved diagnostics and therapy. Clinically, SIRS is identified by two or more symptoms including fever or hypothermia, tachycardia, tachypnoea and change in blood leucocyte count [6]. Thus peripheral vasodilatation, loss of volume due to capillary leakage, myocardial dysfunction and dysfunction of major organs, also summarized as SIRS [7-9]. The open heart surgery for the placement of CF-LVADs or assisted circulation with current CF-LVADs in HF patients may be associated with the development of a systemic inflammatory response that can lead to other clinical complications and dysfunction of major organs. We hypothesize that CF-LVAD support may induce high levels of inflammation either as a result of the exposure to the non-physiological flow condition or as a result of the blood contact with artificial surfaces.

Inflammation is a physiologic mechanism produced in response to injury and is generally controlled at the site of injury. When the local control is lost or an overly activated response results in an exaggerated systemic response, the situation is clinically identified as SIRS [10]. Regardless of its pathogenesis, any insult, if severe enough, induces the release of proinflammatory mediators, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), possibly as a consequence of activation of blood leukocytes or platelets. These ROS react with all kinds of biological substrates, especially with polyunsaturated fatty acids and the latter reaction induces in the host increments of lipid peroxidation metabolites in plasma and cell membrane dysfunction [11]. The reduction of antioxidants is another component of the biological response to the presence of ROS. The imbalance of the redox state reflects an oxidative stress that may constitute a common pathway for life-threatening conditions and be responsible, at least in part, for the tissue damage produced during a systemic response to injury. Earlier study showed that the patients with SIRS, compared with healthy control subjects, had significant depression of plasma total radical-trapping antioxidant variable and increased lipid peroxidation, which suggests that patients with SIRS have altered redox equilibrium [12].

However the development of SIRS after CF-LVAD implantation and the response of antioxidant status, lipid peroxidation and leukocyte activation in clinical settings are limited. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the change of redox status and the concomitant activation of leukocytes in CF-LVAD patients who developed SIRS to clarify whether these biomarkers can reflect systemic inflammation in clinical settings and might be useful markers for post implant SIRS development.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

From 2010 to 2014, we were only able to consent 46 HF patients who were implanted with LVADs, either as a bridge to transplant or destination therapy, at the University of Maryland Medical Center. Not all the patients were consented for the study. Out of 46, we were able to find only 16 patients who meet the criteria for the SIRS within first week after CF-LVAD implantation (SIRS-group). SIRS in those patients was defined according to the guidelines of American College of Chest Physicians and the Society of Critical Care Medicine [13]. On the other hand we had selectively chosen 15 patients form rest of 30 consented patients who did not fall into SIRS criteria. These 15 patients (Non-SIRS) were selected in such a way so that they can match with the SIRS group in respect to their demographic and baseline clinical characteristics. So this study did not represent the whole patient's population during that time frame rather a subgroup of 31 patients from 46 patients. The CF-LVADs implanted included the HeartMate II (Thoratec Corp, Pleasanton, CA) in 12 patients (6 Non-SIRS and 6 SIRS), the Jarvik 2000 (Jarvik Heart, New York, NY) in 10 patients (6 Non-SIRS and 4 SIRS), and the HeartWare HVAD (HeartWare Inc, Framingham, MA) in 9 patients (4 Non-SIRS and 5 SIRS). Most of the HF patients after CF-LVAD implantation remained in intensive care unit (ICU) between 1-14 days depending upon the patient's condition and maximum hospital stay was around 2 months. The SIRS patients had longer ICU and hospitalization history. All the procedures involving collection of human blood were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). All the patients and volunteers gave their written informed consent and were informed about the aim of the study.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the selection of HF patients were: (i) ages between 18 to 70 years, (ii) undergoing CF-LVAD implantation and (iii) able to provide informed consent for the study. The inclusion criteria for the control subjects were (i) no clinical evidence of HF or other cardiovascular diseases, (ii) no history of malignancy and (iii) no inflammatory disease on careful examination and routine laboratory tests. Pregnant or breastfeeding women or women using oral contraceptives were excluded from the study.

Anticoagulation/antiplatelet treatment

After CF-LVAD implantation, anticoagulation was initiated with a titrated heparin dose with the goal for partial thromboplastin time of 40-45s once chest drainage was less than 30 mL/h for at least 4 hours. Thereafter the goal was aimed to have an anti-Xa activity level of 0.1-0.15 U/mL. The anticoagulation medication was subsequently converted to warfarin with a targeted international normalized ratio (INR) from 1.8 to 2.3 for the HeartMate II, 2 to 3 for the Jarvik 2000 and the HeartWare HVAD. Antiplatelet agents were added to the anticoagulation regimen and the dosage was titrated based on measurements of platelet function using a platelet function analyzer (PFA-100®, Dade Behring, Inc, Deerfield, IL) and thrombelastogram (TEG) (TEG® 5000 Thrombelastograph® Hemostasis Analyzer System, Haemonetics Corporation, Braintree, MA). All the patients received pentoxifylline to improve red blood cell (RBC) deformability in the hope of mitigating shear-induced hemolysis.

Collection and preparation of blood sample

EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples from the HF patients were collected before CF-LVAD implant surgery (baseline/pre-operative: Pre-OP) and after one week of implantation (post-operative: Post-OP). Based on the expected post transfusion recovery and life span of transfused platelets, we had collected blood samples after 24 to 48 hours of platelet transfusion (if any). Blood samples from the healthy donors were collected once. Routine laboratory hematology and blood chemistry tests were carried out according to the standard procedures. The blood samples were centrifuged at 2500×g for 10 min at 4°C. The plasma was collected, immediately frozen and stored at – 80°C until analysis. Cycles of freezing and unfreezing were avoided. To optimize the stability of the samples and to minimize the processes of lipid peroxidation in vitro, the samples were stored in tubes free from trace elements.

Assessment of oxidized lipoprotein and lipid peroxidation

The concentration of oxidized low density lipoprotein (oxLDL) in plasma was measured by ELISA using a commercially available kit (Mercodia Inc, Winston Salem, NC) following the manufacturer's instruction. Each sample was assayed in duplicate. The lowest detection limit of the kit was 1.0 mU/L. Malondialdehyde (MDA), an index of lipid peroxidation, was also spectrophotometrically measured using a commercially available kit (Bioxytech LPO-586 Assay, Oxis International, Portland, OR) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Assessment of antioxidant status

The activity of the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD) was assayed in blood erythrocyte lysate spectrophotometrically using a commercially available kit (Cell Technology Inc. Mountain View, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instruction. The absorbance (OD) was measured at 450 nm using the SpectraMax® M3 multi-mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices, California, USA). SOD activity was calculated using SoftMax Pro software (Molecular Devices, California, USA) and expressed as units per milliliters (U/mL). Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) was also measured in blood plasma using a commercially available kit (Randox Laboratories, Antrim, UK) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The OD was measured at 600 nm and the result was expressed as mmol/L.

Assessment of leukocyte activation

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) and polymorphonuclear (PMN)-elastase were measured in blood plasma as indexes of leukocyte activation. Plasma levels of MPO were measured using an MPO-ELISA kit (BioCheck, Inc., Foster City, CA). The assay utilized a unique monoclonal antibody directed against a distinct antigenic determinant on the MPO molecule. This mouse monoclonal anti-MPO antibody was used for solid phase immobilization (on the micro-titter wells). Another mouse monoclonal anti-MPO antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was in the enzyme conjugate solution. The test samples were allowed to react sequentially with these two antibodies, resulting in MPO molecules being sandwiched between the solid phase and enzyme-linked antibodies. After two separate 90- min incubation steps at room temperature with shaking, the wells were rinsed with a washing buffer to remove unbound labeled antibodies. Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) reagent was added and incubated for 20 min with shaking, resulting in the development of color. The color development was stopped with the addition of the stop solution, changing the color to yellow. The concentration of MPO was directly proportional to the color intensity of the test samples. Absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 450 nm. MPO level was determined using the standard curve data using a four-parameter regression model and expressed as ng/mL.

PMN-elastase was measured by an immunoactivation assay using a commercially available PMNElastase ELISA Kit (Merck KGaA; Darmstadt, Germany) following the manufacturer's instruction. This method measures the concentration of PMN-elastase-α1-protease inhibitor complex. Briefly, latex particles are coated with antibody fragments against human PMN-elastase. If elastase is present in the test sample, the latex particles agglutinate and the turbidity in the reaction vessel intensifies. The change in turbidity is measured photometrically. The extent of the turbidity is proportional to the elastase concentration in the test sample. Calibration solutions consisted of PMN-elastase. The results were expressed as ng/mL.

Data analyses

The data are presented as mean±SD (standard deviation) or median with interquartile range (IQR). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (Statistical Package for Social Sciences for windows, release 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical differences were determined by using Chi-square test, Student's t-test and Mann-Whitney U test, as applicable. Univariate analysis was carried out using Spearman's rank correlation test to find out the relation between two measurable parameters as continuous variables, and the result was expressed as ρ (rho) value. Statistical significance was assigned at p<0.05.

Results

Demography and clinical characteristics

In our study, we were only able to include 16 patients who developed SIRS within first week after CF-LVAD implantation. Comparative analyses of demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients in the SIRS group and those who did not experience SIRS (Non-SIRS group) before CF-LVAD implantation were summarized in Table 1. Both the SIRS and Non-SIRS groups were comparable to each other in respect of age, sex, BMI, vital signs, etiology of heart disease and echocardiographic parameters.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of HF patients prior to CF-LVAD implantation

| Characteristics | Pre-implant HF patients (n=31) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Non-SIRS (n=15) | SIRS (n=16) | |

| Demography | ||

| Age in years, median (interquartile range, IQR) | 63(25-76) | 63(48-71) |

| Sex, n (% male) | 13(86.7%) | 14(87.5%) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian white, n (%) | 7(46.7%) | 8(50.0%) |

| Black, n (%) | 8(53.3%) | 8(50.0%) |

| Height in meter, median (IQR) | 1.8(1.7-1.9) | 1.8(1.6-1.9) |

| Weight in kilograms, median (IQR) | 84.0(53.0-119.4) | 88.0(68.9-127.9) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 26.7(19.5-39.0) | 31.2(23.0-38.2) |

| Body surface area (m2), median (IQR) | 2.1(1.6-2.4) | 2.2(1.8-2.5) |

| History of smoking, n (%) | 3(20%) | 4(25.0%) |

| History of substance abuse | ||

| Ethyl alcohol abuse, n (%) | 2(13.3%) | 3(18.7%) |

| Drug abuse, n (%) | 2(13.3%) | 4(25.0%) |

| Vital signs | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), median (IQR) | 106(79-131) | 102(89-107) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), median (IQR) | 64(46-105) | 62(50-65) |

| Etiology of heart disease | ||

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 7(46.7%) | 5(31.3%) |

| Non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 6(40.0%) | 6(37.5%) |

| Idiopathic Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 2(13.3%) | 5(31.3%) |

| Echocardiographic parameters | ||

| Left ventricular end diastolic diameter (mm), median (IQR) | 75(54-88) | 63(62-88) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, (%), median (IQR) | 10(10-20) | 12.5(10-20) |

Adverse Events after Implantation

Table 2 demonstrated common adverse events and clinical complications of the HF patients in both the Non- SIRS and SIRS groups after CF-LVAD implantation. The adverse clinical complications after CF-LVAD implantation were found to be more prominent in the SIRS group.

Table 2.

Adverse events of HF patients with or without SIRS after CF-LVAD implantation

| Adverse events | Pre-implant HF patients (n=31) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Non-SIRS (n =15) | SIRS (n =16) | |

| Major infections | 0 | 5 |

| Renal dysfunction | 4 | 4 |

| Bleeding | 5 | 7 |

| Respiratory failure | 2 | 4 |

| Stroke | 2 | 4 |

| Right ventricular failure | 3 | 6 |

| Device malfunction | 1 | 1 |

Laboratory Hematology and Blood Chemistry

The comparison of routine laboratory hematology and blood chemistry tests between the non-SIRS and SIRS groups before and after CF-LVAD implantation is summarized in Table 3. There were no significant differences in hematology and blood chemistry parameters between the non-SIRS and SIRS groups before CF-LVAD implantation. There were no significant differences in the hematology and blood chemistry parameters between the groups after implantation although we noticed, significantly higher leukocyte counts in both the groups compared to their baseline values. The decreasing trends of erythrocytes, hemoglobin and hematocrit counts were also similar in both groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Laboratory hematology and blood chemistry of non-SIRS and SIRS group of HF patients before (Pre) and after (Post) CF-LVAD implantation

| Variable | Reference value | HF patients (n = 31) Pre-CF-LVAD | Post-CF-LVAD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | ||

| Non-SIRS (n = 15) | SIRS (n = 16) | Non-SIRS (n = 15) | SIRS (n = 16) | ||

| Leukocytes (×103/μL) | 4.5-11.0 | 7.7(3.8-20.9) | 7.7(6.2-15.3) | 14(7.9-35)a | 14.6(8.5-23.8)b |

| Erythrocytes (×106/μL) | 4.0-5.7 | 3.8(3.3-4.5) | 4(3-5) | 3.1(2.8-3.8)a | 3.4(2.7-3.8)b |

| Platelet (×103/μL) | 153-367 | 161(96-478) | 175(110-377) | 178(83-328) | 195.5(77-296) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.6-17.4 | 11.4(9.4-12.7) | 10.7(9.3-14.3) | 9.1(8.1-11.6)a | 9.6(7.9-11.7)b |

| Hematocrit (%) | 37-50 | 34(29-39.2) | 33.3(27.8-42.9) | 26.6(24-34.1)a | 28.4(24.7-34.2)b |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 9-20 | 21(14-52) | 19(18-67) | 21(7-107) | 24(13-73) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.66-1.25 | 1.5(0.6-2.3) | 1.4(1-1.9) | 1(0.5-3.9) | 1.6(0.9-2.3) |

| PTT | 25-28 | 43(30-78) | 33(30-212) | 49(30-88) | 52(32-86)b |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; PTT, partial thromboplastin time. Results are expressed as median with interquartile range (IQR) and a, b, p<0.05 is considered significant in Mann–Whitney U test. I, II, III and IV represents group category.

I vs. III group and

II vs. IV group

Pronounced oxidative stress and SIRS after CF-LVAD implantation

Plasma concentration of oxidized low density lipoprotein (oxLDL: an indicator of oxidative stress) in the HF patients prior to CF-LVAD implantation is shown in Figure 1A. Compared to that in the healthy control group, the concentration of oxLDL in the HF patients was almost 2 times as high as (94.2±6.6 vs 43.2±16.8 U/L, p <0.0001, Student's t-test). There was no significant difference in the baseline levels of oxLDL between the Non-SIRS and SIRS groups. After CF-LVAD implantation, we noticed a significant increase in the levels of oxLDL in both the groups when compared to their corresponding baseline values (figure 1B). However, the post-implant level of oxLDL in the SIRS group was found to be 1.4 times higher compared to that in the Non-SIRS group (166.8±40.8 vs. 121.7±30.5 U/L, p <0.01, Student's t-test). We also noticed that the plasma level of lipid peroxidation product, malondialdehyde (MDA: another indicator of oxidative stress) in the HF patients was 4 times as high as compared to that in the healthy control group (2.67±0.3 vs. 0.68±0.3 μmol/L, p<0.0001) (figure 1C). In the Non-SIRS group, the level of MDA remained unaltered after CF-LVAD implantation while in the SIRS group we noticed a significant increase in the level of MDA to 1.7-fold compared to the baseline value (4.61±1.5 vs. 2.77±0.5 μmol/L, p<0.0001) indicating the oxidative stress was more prominent in the SIRS group (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Change in plasma levels of oxidized low density lipoprotein (oxLDL) and lipid peroxidation product malondialdehyde (MDA) among non-SIRS and SIRS groups before and after CF-LVAD implantation. (A, C) Scatter plots representing the differences in oxLDL and MDA between the control and baseline HF patients. *p<0.05 is considered significant in Student's t-test. (B, D) Box-whisker plot shows differences in oxLDL and MDA before and after CF-LVAD implantation in non-SIRS and SIRS groups. The lines across each box plot represent the median value. The lines that extend from the top and the bottom of each box represent the lowest and highest observations still inside the lower and upper limit of confidence. *p<0.05 is considered significant in Mann–Whitney U-test.

Depletion of antioxidant status and SIRS after CF-LVAD implantation

Significantly lower levels of antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD) in erythrocytes and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) in plasma were noticed in the HF patients than that in the healthy control volunteers (figure 2A,C). There were no significant differences in the baseline levels of SOD and TAC between the Non-SIRS and SIRS groups, respectively. Additionally depleted antioxidant status was noticed in both the SIRS and Non-SIRS groups after CF-LVAD implantation. The lowest levels of SOD and TAC were observed in the SIRS group (figure 2B,D). Thus the antioxidant capacity might not be strong enough to minimize the oxidative stress in the HF patients especially with SIRS after CF-LVAD implantation.

Figure 2.

Change in plasma levels of antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD) and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) among non-SIRS and SIRS groups before and after CF-LVAD implantation. (A, C) Scatter plots representing the differences in SOD and TAC between the control and baseline HF patients. *p<0.05 is considered significant in Student's t-test. (B, D) Box-whisker plot shows differences in SOD and TAC before and after CF-LVAD implantation in non-SIRS and SIRS groups. The lines across each box plot represent the median value. The lines that extend from the top and the bottom of each box represent the lowest and highest observations still inside the lower and upper limit of confidence. *p<0.05 is considered significant in Mann–Whitney U-test.

Excessive leukocyte activation after CF-LVAD implantation

Higher plasma levels of myeloperoxidase (MPO) was found to be the preexisting condition in all the HF patients prior to CF-LVAD implantation when compared to the healthy control volunteers (figure 3A). While the baseline levels of MPO were similar in both the Non-SIRS and SIRS groups, we noticed the MPO level was significantly increased in the SIRS group after CF-LVAD implantation (figure 3B). Although the HF patients prior to CF-LVAD implantation had 29% higher PMN-elastase than the healthy control volunteers, there was no significant difference between them (figure 3C). Post-implant PMNelastase levels were found to be significantly elevated in both the SIRS and Non-SIRS groups when compared to their corresponding baseline values (figure 3D). However, the post-implant level of PMNelastase in the SIRS group was 1.8-times as high as that in the Non-SIRS group (169.4±67.4 vs. 93.1±29.5 ng/mL, p <0.001, Student's t-test).

Figure 3.

Change in plasma levels of myeloperoxidase (MPO) and polymorphonuclear elastase (PMNelastase) among non-SIRS and SIRS groups before and after CF-LVAD implantation. (A, C) Scatter plots representing the differences in MPO and PMN-elastase between the control and baseline HF patients. *p<0.05 is considered significant in Student's t-test. (B, D) Box-whisker plot shows differences in MPO and PMN-elastase before and after CF-LVAD implantation in non-SIRS and SIRS groups. The lines across each box plot represent the median value. The lines that extend from the top and the bottom of each box represent the lowest and highest observations still inside the lower and upper limit of confidence. *p<0.05 is considered significant in Mann–Whitney U-test.

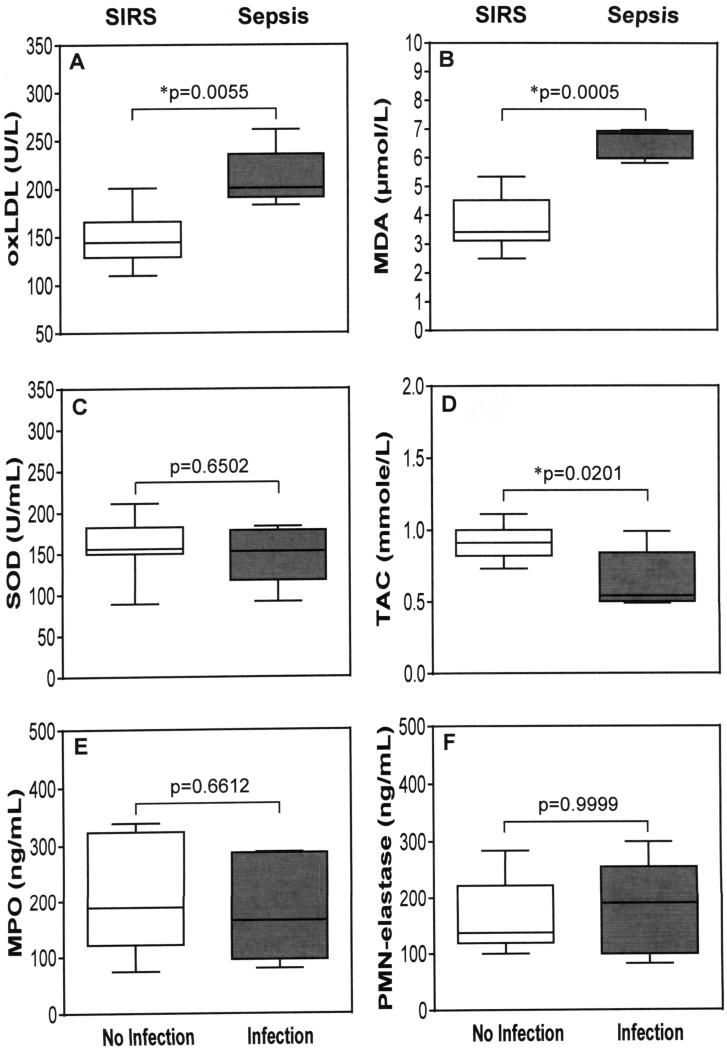

Oxidative stress and leukocyte activation during infection

To further understand the influence of infection, the differences in biomarkers of oxidative stress, antioxidant status and leukocyte activation in the SIRS group between those with and those without major bacterial infections after CF-LVAD implantation are presented in Figure 4. The SIRS patients who had major infection are considered as sepsis. The SIRS patients with major infection had significantly higher plasma levels of oxLDL and MDA indicating elevated oxidative stress when compared to the patients with SIRS alone (Figure 4A-B). Moreover, the antioxidant enzyme SOD and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) were depleted by 6.5% and 31% respectively in the SIRS patients with infection compared to those in the SIRS patients without infection (Figure 4C-D). On the other hand we did not notice any significant change in plasma MPO and PMN-elastase levels between the SIRS patients with infection and the patients with SIRS alone after CF-LVAD implantation (Figure 4E-F).

Figure 4.

Change in oxidative stress, antioxidant status and leukocyte activation due to major infection in SIRS patients (sepsis) after CF-LVAD implantation in compared to SIRS alone. The lines across each box plot represent the median value. The lines that extend from the top and the bottom of each box represent the lowest and highest observations still inside the lower and upper limit of confidence. *p<0.05 is considered significant in Mann–Whitney U-test.

Correlation between leukocyte activation biomarkers and plasma redox status

Spearman's rank correlation analysis showed a positive association between markers of leukocyte activation and markers of oxidative stress in all the HF patients supported by CF-LVAD (Table 4). Conversely, a negative association was found between the markers of leukocyte activation and the levels of antioxidant enzyme SOD and TAC in all the patients. These associations indicated that the HF patients supported with CF-LVAD had elevated oxidative stress and concomitant activation of leukocytes. When we divided the patients according to the occurrence of SIRS or not, we found that the relationship between the markers of leukocyte activation and oxidative stress were more prominent in the SIRS group than the Non-SIRS group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Spearman's rank correlation analysis to test association between oxidative stress and markers of leukocyte activation in both Non-SIRS and SIRS groups of CF-LVAD patients

| Leukocyte activation biomarkers | with oxLDL | with MDA | with SOD | with TAC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ-value | p-value | ρ-value | p-value | ρ-value | p-value | ρ-value | p-value | |

| Plasma MPO | ||||||||

| All | 0.4536 | 0.0002* | 0.3153 | 0.0126* | −0.3743 | 0.0027* | −0.3087 | 0.0146* |

| Non-SIRS | 0.2605 | 0.1644 | −0.01001 | 0.9581 | −0.3394 | 0.0665 | 0.001114 | 0.9953 |

| SIRS | 0.5932 | 0.0003* | 0.5051 | 0.0032* | −0.3764 | 0.0338* | −0.4488 | 0.0100* |

| PMN-elastase | ||||||||

| All | 0.5497 | <0.0001* | 0.3365 | 0.0075* | −0.4205 | 0.0007* | −0.5842 | <0.0001* |

| Non-SIRS | 0.3907 | 0.0328* | −0.08652 | 0.6494 | −0.4876 | 0.0063* | −0.3704 | 0.0439 |

| SIRS | 0.5045 | 0.0032* | 0.4120 | 0.0191* | −0.3932 | 0.0260* | −0.5534 | 0.0010* |

p<0.05, considered as significant

Discussion

There are many experimental evidences from in vitro and animal studies that oxidative stress is common observable fact in heart failure condition [14]. Moreover, in animal models, the development of HF is accompanied by changes in the antioxidant defense mechanisms of the myocardium as well as elevated oxidative myocardial injury. Thus the balance between oxidant and antioxidant systems regulates intracellular redox status, and their imbalance causes oxidative stress, leading to cellular damage in cardiovascular systems [15]. This study is the first report that evaluated the additive role of oxidative stress and leukocyte activation in developing SIRS in the HF patients after CF-LVAD implantation.

In the present study we noticed elevated plasma concentrations of oxLDL and lipid peroxidation product, MDA, and concomitant depletion of SOD activity in blood erythrocytes along with decreased plasma total antioxidant capacity among all the HF patients in our study before CF-LVAD implantation when compared to the healthy control volunteers. Our findings suggest that oxidative stress is a preexisting condition in all the HF patients prior to CF-LVAD implantation. In the HF patients with CF-LVAD, circulating blood is continuously experiencing non-physiological elevated shear stresses and in direct contact with the biomaterials of CF-LVAD. Long-term exposure to the high shear stress flow environment as well as artificial blood contacting materials in CF- LVAD might be responsible for increased oxidative stress and leukocyte activation. In conformity with this we previously showed that CF-LVAD support is related to oxidative stress and concomitant DNA damage in lymphocytes [16].

Moreover, the HF patients who developed SIRS after CF-LVAD implantation had 1.4-times higher levels of oxLDL in plasma compared to the Non-SIRS group. The lipid peroxidation product showed similar results as like oxLDL. On the other hand, the antioxidant capacity was not strong enough to minimize the oxidative stress in the HF patients especially with SIRS after implantation. Our findings support other report that oxidative stress was related to the development of SIRS in critically ill patients admitted to an intensive care unit [17]. Besides SIRS, the HF patients also experienced other adverse events and clinical complications after CF-LVAD implantation (Table 2). In the SIRS group, 5 patients had major infections either at the driveline of the CF-LVAD or in bloodstream, GI tract and mediastinum due to bacterial attack. One patient in the SIRS group had pulmonary infection with unknown cause. All the five SIRS patients having bacterial infection were considered as sepsis because sepsis is the systemic response to infection and is defined as the presence of SIRS in addition to a documented or presumed infection. The status of oxidative stress was found to be elevated in those SIRS patients who had major infections due to bacterial attack when compared to the patients with SIRS only. Thus, the role of oxidative stress during sepsis (SIRS + infection) is also evident in our study.

In our study, the plasma concentrations of MPO and PMN-elastase were measured as an index of leukocyte activation. We found pre-existing higher levels of MPO in all the HF patients prior to CFLVAD implantation when compared to that in the healthy control volunteers while no such elevation was observed in case of PMN-elastase level. MPO is a known marker of inflammatory status, and elevated plasma MPO level reflects a heightened inflammatory state. Malle and coworkers [18] have reviewed the role of MPO and its generated oxidants to modify LDL which is a major source of lipids in atherosclerosis. Various studies link plasma MPO concentration with the presence of HF [19,20] and left ventricular dysfunction [21,22]. Elevated plasma concentration of MPO was also evident in patients with systemic inflammation [17]. The results of Spearman's rank correlation test exhibited significant positive association between plasma MPO and oxidative stress biomarkers as well as negative association with antioxidant capacity among CF-LVAD patients who developed SIRS. Besides the role of MPO as biomarker of leukocyte activation among the CF-LVAD patients with SIRS, other studies also showed that plasma MPO level is one of the most promising biomarkers of oxidative stress for clinical cardiologists [23].

During the activation of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, the cytotoxic molecules especially PMNelastase is released into the plasma. We noticed a significantly elevated plasma level of PMN-elastase among the HF patients with SIRS after CF-LVAD implantation compared to that in the non-SIRS group. Our finding is in general agreement with other investigations that showed elevated levels of PMN-elastase among the patients who fulfilled all the SIRS criteria [24]. This elevation might be related to persistent oxidative stress among these patients after the implant surgery especially in the SIRS group.

In summary, we concluded that the plasma redox status and leukocyte activation became more prominent in CF-LVAD patients who developed SIRS. Our findings suggest that plasma biomarkers of oxidative stress and leukocyte activation are associated with the development of SIRS after CF-LVAD implant surgery. We acknowledge that there are some limitations in this prospective observational study. This is a single-center study and the sample size was relatively small. Not all CF-LVAD patients were enrolled for this study. The effects of medications on oxidative stress and leukocyte activation may need to be explored. Medication side effects or pharmacologic properties may either induce or mask SIRS. Recent changes in medications should be addressed in further studies to rule out drug-drug interactions or a new side effect. A larger cohort of CF-LVAD patients with SIRS and other associated clinical complications is needed to confirm our initial findings.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: The described research was partially sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (Grant R01 HL 088100).

Footnotes

Disclosure

All authors report no disclosures relevant to this work.

References

- 1.Birks EJ, Tansley PD, Hardy J, et al. Left ventricular assist device and drug therapy for the reversal of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1873–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lietz K. Destination therapy: patient selection and current outcomes. J Card Surg. 2010;25:462–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2010.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lahpor J, Khaghani A, Hetzer R, et al. European results with a continuous-flow ventricular assist device for advanced heart failure patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:357–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crow S, John R, Boyle A, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding rates in recipients of nonpulsatile and pulsatile left ventricular assist devices. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stern DR, Kazam J, Edwards P, et al. Increased incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding following implantation of the HeartMate II LVAD. J Card Surg. 2010;25:352–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2010.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comstedt P, Storgaard M, Lassen AT. The Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) in acutely hospitalised medical patients: a cohort study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:67. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-17-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieman G, Searles B, Carney D, et al. Systemic inflammation induced by cardiopulmonary bypass: a review of pathogenesis and treatment. J Extra Corpor Technol. 1999;31:202–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prondzinsky R, Müller-Werdan U, Pilz G, et al. Systemic inflammatory reactions to extracorporeal therapy measures (II): Cardiopulmonary bypass. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1997;109:346–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asimakopoulos G. Systemic inflammation and cardiac surgery: an update. Perfusion. 2001;16:353–60. doi: 10.1177/026765910101600505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis MG, Hagen PO. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Br J Surg. 1997;84:920–35. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800840707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu BP. Cellular defenses against damage from reactive species. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:139–62. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsal K, Hsu TG, Kong CW, et al. Is the endogenous peroxyl-radical scavenging capacity of plasma protective in systemic inflammatory disorders in human?. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:926–33. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101:1644–55. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mak S, Newton GE. The oxidative stress hypothesis of congestive heart failure: radical thoughts. Chest. 2001;120:2035–46. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.6.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimokawa H, Satoh K. Light and Dark of Reactive Oxygen Species for Vascular Function. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2014 Aug 26; doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000159. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mondal NK, Sorensen E, Hiivala N, et al. Oxidative stress, DNA damage and repair in heart failure patients after implantation of continuous flow left ventricular assist devices. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:883–93. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alonso de Vega JM, Díaz J, Serrano E, et al. Oxidative stress in critically ill patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1782–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malle E, Marsche G, Arnhold J, et al. Modification of low-density lipoprotein by myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants and reagent hypochlorous acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:392–415. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang WH, Brennan ML, Philip K, et al. Plasma myeloperoxidase levels in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:796–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang WH, Tong W, Troughton RW, et al. Prognostic value and echocardiographic determinants of plasma myeloperoxidase levels in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2364–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudolph V, Rudolph TK, Hennings JC, et al. Activation of polymorphonuclear neutrophils in patients with impaired left ventricular function. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng LL, Pathik B, Loke IW, et al. Myeloperoxidase and Creactive protein augment the specificity of B-type natriuretic peptide in community screening for systolic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2006;152:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schindhelm RK, van der Zwan LP, Teerlink T, et al. Myeloperoxidase: a useful biomarker for cardiovascular disease risk stratification? Clinical Chemistry. 2009;55:1462–70. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.126029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakamoto Y, Mashiko K, Matsumoto H, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome score at admission predicts injury severity, organ damage and serum neutrophil elastase production in trauma patients. J Nippon Med Sch. 2010;77:138–44. doi: 10.1272/jnms.77.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]