Abstract

Pathogen infection triggers complex molecular perturbations within host cells that results in either resistance or susceptibility. Protein acetylation is an emerging biochemical modification that appears to play central roles during host–pathogen interactions. To date, research in this area has focused on two main themes linking protein acetylation to plant immune signaling. Firstly, it has been established that proper gene expression during defense responses requires modulation of histone acetylation within target gene promoter regions. Second, some pathogens can deliver effector molecules that encode acetyltransferases directly within the host cell to modify acetylation of specific host proteins. Collectively these findings suggest that the acetylation level for a range of host proteins may be modulated to alter the outcome of pathogen infection. This review will focus on summarizing our current understanding of the roles of protein acetylation in plant defense and highlight the utility of proteomics approaches to uncover the complete repertoire of acetylation changes triggered by pathogen infection.

Keywords: acetylation, plant–pathogen interaction, defense, proteomics, post-translational modification

Introduction

Protein lysine acetylation is a reversible covalent modification that was first discovered on histones more than 50 years ago (Phillips, 1963; Allfrey et al., 1964; Verdin and Ott, 2015). In general hyperacetylation of histone proteins is associated with an open chromatin state and active transcription whereas histone deacetylation is associated with closed chromatin and a repressed transcriptional state. Additionally, histone acetylation recruits “reader” proteins (e.g., bromodomain containing proteins) that bind acetylated lysines enabling further modulation of the transcriptional state (Kouzarides, 2007; Verdin and Ott, 2015).

While protein acetylation was originally discovered on histones specifically it has long been known that non-histone proteins are also acetylated (Sterner et al., 1978; Verdin and Ott, 2015). Initially, studies focused on the role of non-histone acetylation of individual proteins. These studies demonstrated that many different types of proteins are acetylated, such as transcription factors, nuclear receptors, cytoskeletal proteins, and enzymes involved in metabolism. Additionally, acetylation was shown to modify protein function by affecting the three-dimensional structure, activity, stability, transportation and/or degradation of non-histone proteins (Glozak et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2010; Verdin and Ott, 2015). Due to the growing recognition of the importance and potential biological impact of protein acetylation a number of labs worked to develop proteomic methodology to globally detect and quantify lysine acetylation.

Global MS Proteomics

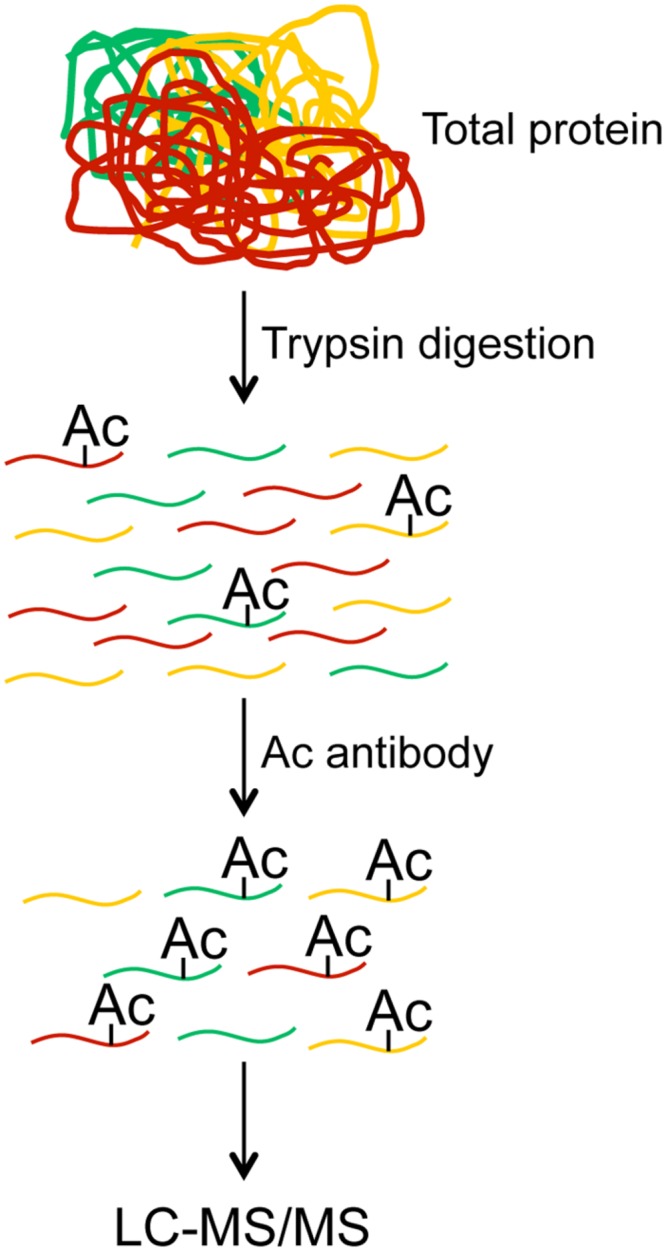

In the past two decades the field of MS based proteomics has rapidly matured to the point where we can routinely detect and quantify 5–10 1000 proteins in a single run (Nagaraj et al., 2011; Walley et al., 2013, 2015). However, the low abundance of acetylated proteins prevented global identification and quantification of lysine acetylation. This challenge was recently overcome by the development of pan anti-acetyllysine antibodies that recognize acetylated lysine irrespective of surrounding amino acids. By coupling acetyllysine immunopurification with MS based proteomics researchers are now able to globally profile lysine acetylation (Choudhary et al., 2009; Mertins et al., 2013). In this approach the anti-acetyllysine antibodies are employed in a technical strategy similar to the one outlined in Figure 1. Specifically, total proteins are extracted from cells or tissues, then the total proteins are digested to peptides, and the acetylated peptides are enriched using the anti-acetyllysine antibodies. Following enrichment the acetylated peptides are detected and quantified by using LC–MS/MS methods. Using this methodology, 100s and 1000s of acetylated sites have been identified in plants and non-plant eukaryotic systems, respectively. Organisms that have been utilized for either global or organellar acetylome profiling include Arabidopsis (Finkemeier et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2011; Konig et al., 2014), rice (Nallamilli et al., 2014), soybean (Smith-Hammond et al., 2014b), pea (Smith-Hammond et al., 2014a), grape (Melo-Braga et al., 2012), strawberry (Fang et al., 2015), human (Choudhary et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2010; Barjaktarovic et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015; Scholz et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015), mouse (Yang et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012; Fritz et al., 2012; Hebert et al., 2013; Masri et al., 2013; Holper et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2015), rat (Bouchut et al., 2015), Drosophila (Weinert et al., 2011; Feller et al., 2015), silkworm (Nie et al., 2015), yeast (Downey et al., 2015), Toxoplasma gondii (Xue et al., 2013), Escherichia coli (Zhang et al., 2013; Castano-Cerezo et al., 2014), and other bacteria (Okanishi et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2013; Liao et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2014; Pan et al., 2014; Kosono et al., 2015; Mo et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2015). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that non-histone acetylation is a common modification in different systems and suggest that acetylation plays and essential role in a myriad of biological processes.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of typical proteomic workflows for acetylome profiling.

Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Ac

Lysine acetylation is typically regulated by enzymes that add or remove acetyl groups. Specifically, lysine acetyltransferases (also termed HATs) have been shown to acetylate both histone and non-histone proteins (Sterner and Berger, 2000). Lysine acetyltransferases are divided, based on homology, into three different families, GNAT, MYST, and CBP/P300 (Kouzarides, 2007). Conversely, acetyl groups are removed from the acetylated proteins by lysine deacetylases (also termed HDACs; Kouzarides, 2007; Haery et al., 2015). Thus, protein acetylation levels are dynamically regulated by lysine acetyltransferases and deacetylases. Intriguingly, recent studies have demonstrated that protein acetylation is not only controlled enzymatically, but that it is also modulated non-enzymatically by metabolic intermediates including Acetyl-CoA and NAD+, which is required for activity of sirtuin type deacetylases (Choudhary et al., 2009; Cai et al., 2011; Lu and Thompson, 2012; Shen et al., 2015).

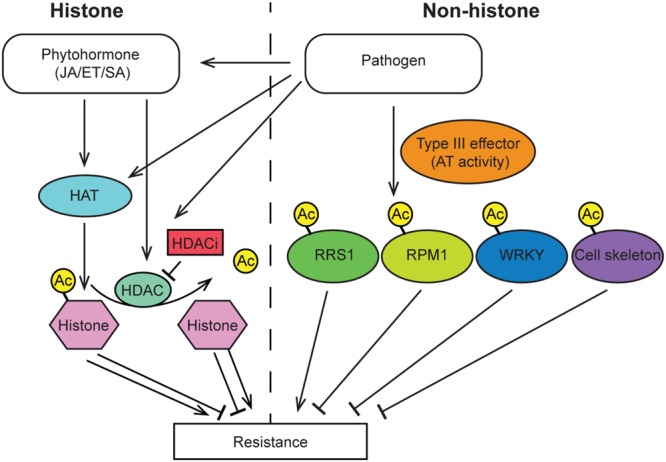

Histone Ac and Defense in Plants

Acetylation is a common modification of histones 3 and 4. Generally, histone acetylation is enriched in the promoter region of genes, which functions to open the chromatin and enable gene expression (Figure 2). Studies have found that the expression level of HAT genes is induced by treatment with hormones as well as pathogen infection (Liu et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2015). Consistently, the level and pattern of histone acetylation is altered by pathogen infection. Finally, the maize fungal pathogen Cochliobolus carbonum produces the effector molecule HC-toxin, which functions as a HDACi and is required for pathogen virulence (Johal and Briggs, 1992; Brosch et al., 1995; Ransom and Walton, 1997; Sindhu et al., 2008). Taken together these studies indicate that histone acetylation levels may play an important role in defense.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of histone and non-histone protein acetylation events that have been demonstrated to alter plant immunity. Pathogen infection results in modulation of HAT and HDAC activity, which alters the histone acetylation state of specific defense gene promoters thereby promoting either susceptibility or resistance. Several pathogen effector proteins encode acetyltransferase enzymes that directly acetylate host proteins and alter plant immunity. JA, jasmonic acid; ET, ethylene; SA, salicylic acid; HAT, histone acetyltransferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HDACi, histone deacetylase inhibitor; RRS1, Toll/Interleukin1 receptor type R protein; RPM1, intracellular nucleotide binding-leucine-rich repeat R protein.

In line with these observations, a direct role for HDACs in modulating histone acetylation of defense genes and thereby plant resistance has been shown. The transcription level of Histone Deacetylase701 (HDT701), a member of the plant-specific HD2 subfamily of HDACs in rice, is increased in the compatible reaction and decreased in the incompatible reaction after infection by the fungal pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae (Ding et al., 2012). Critically, overexpression of HDT701 in transgenic rice leads to decreased levels of histone H4 acetylation and enhanced susceptibility to the rice pathogens M. oryzae and Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo). In contrast, silencing of HDT701 in transgenic rice causes elevated levels of histone H4 acetylation and elevated transcription of PRR and defense-related genes, increased generation of reactive oxygen species after pathogen-associated molecular pattern elicitor treatment, as well as enhanced resistance to both M. oryzae and Xoo.

In Arabidopsis, the RPD3-type histone deacetylases HDA6 and HDA19 have been extensively studied in the context of plant immunity. HDA19 modulates histone acetylation and is a positive regulator of JA/ET signaling pathways. Consistently, HDA19 modulates resistance to pathogens sensitive to JA/ET mediated immunity such as Alternaria brassicicola (Zhou et al., 2005). Conversely, HDA19 appears to play a negative role in SA mediated signaling and defense (Choi et al., 2012). Furthermore, HDA19 interacts with the transcription factors WRKY38 and WRKY62, which are negative regulators of SA defense signaling, to fine tune basal defense responses (Kim et al., 2008). Finally, HDA6 acts as a corepressor with JA-Zim domain (JAZ) proteins to repress EIN3/EIL1 dependent transcriptional responses and thereby JA signaling.

Histone acetyltransfersases have also been demonstrated to modulate Arabidopsis immunity via Elongator mediated gene regulation. Recent studies established that Arabidopsis Elongator complex mutants exhibit altered histone acetylation and target gene expression patterns, leading to altered pathogen resistance phenotypes. Specifically, mutation of Elongator subunit 2 (ELP2) reduces the histone acetylation level in the coding region of several plant defense genes, including PLANT DEFENSIN1.2 (PDF1.2), WRKY33 and OCTADECANOID-RESPONSIVE ARABIDOPSIS AP2/ERF59 (ORA59), which results in the repression of these genes and leads to suppression of plant defense (Wang et al., 2013, 2015). Mutation of another Elongator complex subunit, AtELP3, results in similar immune deficiencies as ELP2. AtELP3 has also been demonstrated to have HAT activity. Collectively these findings indicate that the Elongator complex is involved in both basal immunity and ETI (Defraia et al., 2013).

Non-Histone Ac in Plant Immunity

While the majority of research has investigated the role of histone acetylation in defense there are several studies that have established a role for non-histone protein acetylation in plant immunity. For instance, pathogen produced type III effectors can acetylate selected non-histone proteins in host cells, thereby triggering plant immunity response (Figure 2). One example of such an interaction is from the type III secreted effector, HopZ1a, which is secreted by Pseudomonas syringae and functions as an acetyltransferase. HopZ1 is able to self-acetylate and acetylate tubulin, which results in the destruction of plant microtubule networks, inhibits protein secretion and ultimately suppresses cell-wall mediated defense (Lee et al., 2012). A similar mechanism was found for the effector protein AvrBsT that also acts as an acetyltransferase and acetylates ACIP1, which is required for plant defense. Acetylation of ACIP1 alters the co-localization pattern of ACIP1 and microtubules (Cheong et al., 2014). Additionally, another type III secreted effector, PopP2, a YopJ-like effector from the soil borne root pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum, also has acetyltransferase activity. PopP2 directly acetylates the C-terminal WRKY transcription factor domain of the NLR RRS1 as well as WRKY transcription factors. Acetylation of RRS1 or WRKYs abolishes DNA binding activity. In the case of RRS1 acetylation, RPS4 dependent immunity is activated. Conversely, acetylation of WRKY transcription factors results in immune suppression (Tasset et al., 2010; Le Roux et al., 2015; Sarris et al., 2015). Finally, a new type III effecter HopZ3 from the plant pathogen P. syringae, have been found to acetylate multiple members of the RPM1 immune complex and depress plant immunity response (Lee et al., 2015).

Perspective

Lysine acetylation has emerged as a major post-translational modification impacting a diverse array of cellular processes. In the context of plant defense signaling it is well established that modulation of histone acetylation levels of defense genes is critical for appropriate immune responses. There is also mounting evidence that acetylation of non-histone proteins impacts plant immunity. However, to date non-histone protein acetylation of plant proteins has only been shown to result from pathogen effectors that encode acetyltransferase enzymes. This raises the question of whether plant HATs or HDACs directly modulate acetylation status of non-histone proteins during pathogen infection. The recent development of robust proteomic methodologies to globally identify and quantify lysine acetylation enables us to now identify proteome-wide changes in acetylation triggered during immune responses. Detailed follow-up studies of specific alterations in acetylation triggered by pathogen infection should shed light on whether plants directly modulate non-histone protein acetylation during defense signaling.

Author Contributions

All authors listed, have made substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- ET

Ethylene

- ETI

effector-triggered immunity

- HATs

histone acetyltransfersases

- HDACs

histone deactylases

- HDACi

histone deacetylase inhibitor

- JA

jasmonic acid

- LC–MS/MS

liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NLR

nucleotide-binding/leucine-rich repeat receptor

- PRR

pattern recognition receptor

- SA

salicylic acid

Footnotes

Funding. Funding was provided by a start-up grant to JW from Iowa State University.

References

- Allfrey V. G., Faulkner R., Mirsky A. E. (1964). Acetylation and methylation of histones and their possible role in the regulation of RNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 51 786–794. 10.1073/pnas.51.5.786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barjaktarovic Z., Kempf S. J., Sriharshan A., Merl-Pham J., Atkinson M. J., Tapio S. (2015). Ionizing radiation induces immediate protein acetylation changes in human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells. J. Radiat. Res. 56 623–632. 10.1093/jrr/rrv014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchut A., Chawla A. R., Jeffers V., Hudmon A., Sullivan W. J., Jr. (2015). Proteome-wide lysine acetylation in cortical astrocytes and alterations that occur during infection with brain parasite Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS ONE 10:e0117966 10.1371/journal.pone.0117966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch G., Ransom R., Lechner T., Walton J. D., Loidl P. (1995). Inhibition of maize histone deacetylases by HC toxin, the host-selective toxin of Cochliobolus carbonum. Plant Cell 7 1941–1950. 10.2307/3870201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L., Sutter B. M., Li B., Tu B. P. (2011). Acetyl-CoA induces cell growth and proliferation by promoting the acetylation of histones at growth genes. Mol. Cell. 42 426–437. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano-Cerezo S., Bernal V., Post H., Fuhrer T., Cappadona S., Sanchez-Diaz N. C., et al. (2014). Protein acetylation affects acetate metabolism, motility and acid stress response in Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 10:762 10.15252/msb.20145227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Zhao W., Yang J. S., Cheng Z., Luo H., Lu Z., et al. (2012). Quantitative acetylome analysis reveals the roles of SIRT1 in regulating diverse substrates and cellular pathways. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11 1048–1062. 10.1074/mcp.M112.019547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong M. S., Kirik A., Kim J. G., Frame K., Kirik V., Mudgett M. B. (2014). AvrBsT acetylates Arabidopsis ACIP1, a protein that associates with microtubules and is required for immunity. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1003952 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. M., Song H. R., Han S. K., Han M., Kim C. Y., Park J., et al. (2012). HDA19 is required for the repression of salicylic acid biosynthesis and salicylic acid-mediated defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 71 135–146. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04977.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary C., Kumar C., Gnad F., Nielsen M. L., Rehman M., Walther T. C., et al. (2009). Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science 325 834–840. 10.1126/science.1175371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defraia C. T., Wang Y., Yao J., Mou Z. (2013). Elongator subunit 3 positively regulates plant immunity through its histone acetyltransferase and radical S-adenosylmethionine domains. BMC Plant Biol. 13:102 10.1186/1471-2229-13-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding B., Bellizzi Mdel R., Ning Y., Meyers B. C., Wang G. L. (2012). HDT701, a histone H4 deacetylase, negatively regulates plant innate immunity by modulating histone H4 acetylation of defense-related genes in rice. Plant Cell 24 3783–3794. 10.1105/tpc.112.101972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey M., Johnson J. R., Davey N. E., Newton B. W., Johnson T. L., Galaang S., et al. (2015). Acetylome profiling reveals overlap in the regulation of diverse processes by sirtuins, gcn5, and esa1. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14 162–176. 10.1074/mcp.M114.043141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X., Chen W., Zhao Y., Ruan S., Zhang H., Yan C., et al. (2015). Global analysis of lysine acetylation in strawberry leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 6:739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller C., Forne I., Imhof A., Becker P. B. (2015). Global and specific responses of the histone acetylome to systematic perturbation. Mol. Cell 57 559–571. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkemeier I., Laxa M., Miguet L., Howden A. J., Sweetlove L. J. (2011). Proteins of diverse function and subcellular location are lysine acetylated in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 155 1779–1790. 10.1104/pp.110.171595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz K. S., Galligan J. J., Hirschey M. D., Verdin E., Petersen D. R. (2012). Mitochondrial acetylome analysis in a mouse model of alcohol-induced liver injury utilizing SIRT3 knockout mice. J. Proteome Res. 11 1633–1643. 10.1021/pr2008384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glozak M. A., Sengupta N., Zhang X., Seto E. (2005). Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins. Gene 363 15–23. 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haery L., Thompson R. C., Gilmore T. D. (2015). Histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases in B- and T-cell development, physiology and malignancy. Genes Cancer 6 184–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert A. S., Dittenhafer-Reed K. E., Yu W., Bailey D. J., Selen E. S., Boersma M. D., et al. (2013). Calorie restriction and SIRT3 trigger global reprogramming of the mitochondrial protein acetylome. Mol. Cell. 49 186–199. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holper S., Nolte H., Bober E., Braun T., Kruger M. (2015). Dissection of metabolic pathways in the Db/Db mouse model by integrative proteome and acetylome analysis. Mol. Biosyst. 11 908–922. 10.1039/c4mb00490f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johal G. S., Briggs S. P. (1992). Reductase activity encoded by the HM1 disease resistance gene in maize. Science 258 985–987. 10.1126/science.1359642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. C., Lai Z., Fan B., Chen Z. (2008). Arabidopsis WRKY38 and WRKY62 transcription factors interact with histone deacetylase 19 in basal defense. Plant Cell 20 2357–2371. 10.1105/tpc.107.055566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. J., Kwon O. K., Ki S. H., Jeong T. C., Lee S. (2015). Characterization of novel mechanisms for steatosis from global protein hyperacetylation in ethanol-induced mouse hepatocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 463 832–838. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig A. C., Hartl M., Boersema P. J., Mann M., Finkemeier I. (2014). The mitochondrial lysine acetylome of Arabidopsis. Mitochondrion 19(Pt B) 252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosono S., Tamura M., Suzuki S., Kawamura Y., Yoshida A., Nishiyama M., et al. (2015). Changes in the acetylome and succinylome of Bacillus subtilis in response to carbon source. PLoS ONE 10:e0131169 10.1371/journal.pone.0131169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. (2007). Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128 693–705. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux C., Huet G., Jauneau A., Camborde L., Tremousaygue D., Kraut A., et al. (2015). A receptor pair with an integrated decoy converts pathogen disabling of transcription factors to immunity. Cell 161 1074–1088. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A. H., Hurley B., Felsensteiner C., Yea C., Ckurshumova W., Bartetzko V., et al. (2012). A bacterial acetyltransferase destroys plant microtubule networks and blocks secretion. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002523 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Manning A. J., Wolfgeher D., Jelenska J., Cavanaugh K. A., Xu H., et al. (2015). Acetylation of an NB-LRR plant immune-effector complex suppresses immunity. Cell Rep. 13 1670–1682. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao G., Xie L., Li X., Cheng Z., Xie J. (2014). Unexpected extensive lysine acetylation in the trump-card antibiotic producer Streptomyces roseosporus revealed by proteome-wide profiling. J. Proteomics 106 260–269. 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Yang M., Wang X., Yang S., Gu J., Zhou J., et al. (2014). Acetylome analysis reveals diverse functions of lysine acetylation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13 3352–3366. 10.1074/mcp.M114.041962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Liu S., Bode L., Liu C., Zhang L., Wang X., et al. (2015). Persistent human Borna disease virus infection modifies the acetylome of human oligodendroglia cells towards higher energy and transporter levels. Virology 485 58–78. 10.1016/j.virol.2015.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Luo M., Zhang W., Zhao J., Zhang J., Wu K., et al. (2012). Histone acetyltransferases in rice (Oryza sativa L.): phylogenetic analysis, subcellular localization and expression. BMC Plant Biol. 12:145 10.1186/1471-2229-12-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C., Thompson C. B. (2012). Metabolic regulation of epigenetics. Cell Metab. 16 9–17. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masri S., Patel V. R., Eckel-Mahan K. L., Peleg S., Forne I., Ladurner A. G., et al. (2013). Circadian acetylome reveals regulation of mitochondrial metabolic pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 3339–3344. 10.1073/pnas.1217632110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo-Braga M. N., Verano-Braga T., Leon I. R., Antonacci D., Nogueira F. C., Thelen J. J., et al. (2012). Modulation of protein phosphorylation. N-glycosylation and Lys-acetylation in grape (Vitis vinifera) mesocarp and exocarp owing to Lobesia botrana infection. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11 945–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertins P., Qiao J. W., Patel J., Udeshi N. D., Clauser K. R., Mani D. R., et al. (2013). Integrated proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications by serial enrichment. Nat. Methods 10 634–637. 10.1038/nmeth.2518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo R., Yang M., Chen Z., Cheng Z., Yi X., Li C., et al. (2015). Acetylome analysis reveals the involvement of lysine acetylation in photosynthesis and carbon metabolism in the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Proteome Res. 14 1275–1286. 10.1021/pr501275a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj N., Wisniewski J. R., Geiger T., Cox J., Kircher M., Kelso J., et al. (2011). Deep proteome and transcriptome mapping of a human cancer cell line. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7:548 10.1038/msb.2011.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallamilli B. R., Edelmann M. J., Zhong X., Tan F., Mujahid H., Zhang J., et al. (2014). Global analysis of lysine acetylation suggests the involvement of protein acetylation in diverse biological processes in rice (Oryza sativa). PLoS ONE 9:e89283 10.1371/journal.pone.0089283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z., Zhu H., Zhou Y., Wu C., Liu Y., Sheng Q., et al. (2015). Comprehensive profiling of lysine acetylation suggests the widespread function is regulated by protein acetylation in the silkworm. Bombyx mori. Proteomics 15 3253–3266. 10.1002/pmic.201500001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okanishi H., Kim K., Masui R., Kuramitsu S. (2013). Acetylome with structural mapping reveals the significance of lysine acetylation in Thermus thermophilus. J. Proteome Res. 12 3952–3968. 10.1021/pr400245k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J., Ye Z., Cheng Z., Peng X., Wen L., Zhao F. (2014). Systematic analysis of the lysine acetylome in Vibrio parahemolyticus. J. Proteome Res. 13 3294–3302. 10.1021/pr500133t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips D. M. (1963). The presence of acetyl groups of histones. Biochem. J. 87 258–263. 10.1042/bj0870258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom R. F., Walton J. D. (1997). Histone hyperacetylation in maize in response to treatment with HC-Toxin or infection by the filamentous fungus Cochliobolus carbonum. Plant Physiol. 115 1021–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarris P. F., Duxbury Z., Huh S. U., Ma Y., Segonzac C., Sklenar J., et al. (2015). A Plant immune receptor detects pathogen effectors that target WRKY transcription factors. Cell 161 1089–1100. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz C., Weinert B. T., Wagner S. A., Beli P., Miyake Y., Qi J., et al. (2015). Acetylation site specificities of lysine deacetylase inhibitors in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 33 415–423. 10.1038/nbt.3130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Wei W., Zhou D. X. (2015). Histone acetylation enzymes coordinate metabolism and gene expression. Trends Plant Sci. 20 614–621. 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu A., Chintamanani S., Brandt A. S., Zanis M., Scofield S. R., Johal G. S. (2008). A guardian of grasses: specific origin and conservation of a unique disease-resistance gene in the grass lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 1762–1767. 10.1073/pnas.0711406105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B. N., Zhang G., Hwa Y. L., Li J., Dowdy S. C., Jiang S. W. (2010). Nonhistone protein acetylation as cancer therapy targets. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 10 935–954. 10.1586/era.10.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Hammond C. L., Hoyos E., Miernyk J. A. (2014a). The pea seedling mitochondrial Nepsilon-lysine acetylome. Mitochondrion 19(Pt B) 154–165. 10.1016/j.mito.2014.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Hammond C. L., Swatek K. N., Johnston M. L., Thelen J. J., Miernyk J. A. (2014b). Initial description of the developing soybean seed protein Lys-N(epsilon)-acetylome. J. Proteomics 96 56–66. 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner D. E., Berger S. L. (2000). Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64 435–459. 10.1128/MMBR.64.2.435-459.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner R., Vidali G., Heinrikson R. L., Allfrey V. G. (1978). Postsynthetic modification of high mobility group proteins. Evidence that high mobility group proteins are acetylated. J. Biol. Chem. 253 7601–7604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasset C., Bernoux M., Jauneau A., Pouzet C., Briere C., Kieffer-Jacquinod S., et al. (2010). Autoacetylation of the Ralstonia solanacearum effector PopP2 targets a lysine residue essential for RRS1-R-mediated immunity in Arabidopsis. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001202 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdin E., Ott M. (2015). 50 years of protein acetylation: from gene regulation to epigenetics, metabolism and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16 258–264. 10.1038/nrm3931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley J., Xiao Y., Wang J. Z., Baidoo E. E., Keasling J. D., Shen Z., et al. (2015). Plastid-produced interorgannellar stress signal MEcPP potentiates induction of the unfolded protein response in endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 6212–6217. 10.1073/pnas.1504828112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley J. W., Shen Z., Sartor R., Wu K. J., Osborn J., Smith L. G., et al. (2013). Reconstruction of protein networks from an atlas of maize seed proteotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 E4808–E4817. 10.1073/pnas.1319113110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Ding Y., Yao J., Zhang Y., Sun Y., Colee J., et al. (2015). Arabidopsis Elongator subunit 2 positively contributes to resistance to the necrotrophic fungal pathogens Botrytis cinerea and Alternaria brassicicola. Plant J. 83 1019–1033. 10.1111/tpj.12946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., An C., Zhang X., Yao J., Zhang Y., Sun Y., et al. (2013). The Arabidopsis elongator complex subunit2 epigenetically regulates plant immune responses. Plant Cell 25 762–776. 10.1105/tpc.113.109116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert B. T., Wagner S. A., Horn H., Henriksen P., Liu W. R., Olsen J. V., et al. (2011). Proteome-wide mapping of the Drosophila acetylome demonstrates a high degree of conservation of lysine acetylation. Sci. Signal. 4:ra48 10.1126/scisignal.2001902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q., Cheng Z., Zhu J., Xu W., Peng X., Chen C., et al. (2015). Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid treatment reveals crosstalks among proteome, ubiquitylome and acetylome in non-small cell lung cancer A549 cell line. Sci. Rep. 5:9520 10.1038/srep09520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Oh M. H., Schwarz E. M., Larue C. T., Sivaguru M., Imai B. S., et al. (2011). Lysine acetylation is a widespread protein modification for diverse proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 155 1769–1778. 10.1104/pp.110.165852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Vellaichamy A., Wang D., Zamdborg L., Kelleher N. L., Huber S. C., et al. (2013). Differential lysine acetylation profiles of Erwinia amylovora strains revealed by proteomics. J. Proteomics 79 60–71. 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L., Wang X., Zeng J., Zhou M., Duan X., Li Q., et al. (2015). Proteome-wide lysine acetylation profiling of the human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 59 193–202. 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Xu H., Liu Y., Wang X., Xu Q., Deng X. (2015). Genome-wide identification of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) histone modification gene families and their expression analysis during the fruit development and fruit-blue mold infection process. Front. Plant Sci. 6:607 10.3389/fpls.2015.00607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue B., Jeffers V., Sullivan W. J., Uversky V. N. (2013). Protein intrinsic disorder in the acetylome of intracellular and extracellular Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Biosyst. 9 645–657. 10.1039/c3mb25517d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Vaitheesvaran B., Hartil K., Robinson A. J., Hoopmann M. R., Eng J. K., et al. (2011). The fasted/fed mouse metabolic acetylome: N6-acetylation differences suggest acetylation coordinates organ-specific fuel switching. J. Proteome Res. 10 4134–4149. 10.1021/pr200313x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Zheng S., Yang J. S., Chen Y., Cheng Z. (2013). Comprehensive profiling of protein lysine acetylation in Escherichia coli. J. Proteome Res. 12 844–851. 10.1021/pr300912q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Xu W., Jiang W., Yu W., Lin Y., Zhang T., et al. (2010). Regulation of cellular metabolism by protein lysine acetylation. Science 327 1000–1004. 10.1126/science.1179689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C., Zhang L., Duan J., Miki B., Wu K. (2005). HISTONE DEACETYLASE19 is involved in jasmonic acid and ethylene signaling of pathogen response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17 1196–1204. 10.1105/tpc.104.028514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]