Abstract

Background and purpose — Recent research on outcomes after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has raised the question of the ability of traditional outcome measures to distinguish between treatments. We compared functional outcomes in patients undergoing TKA with and without patellar resurfacing, using the knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS) as the primary outcome and 3 traditional outcome measures as secondary outcomes.

Patients and methods — 129 knees in 115 patients (mean age 70 (42–82) years; 67 female) were evaluated in this single-center, randomized, double-blind study. Data were recorded preoperatively, at 1 year, and at 3 years, and were assessed using repeated-measures mixed models.

Results — The mean subscores for the KOOS after surgery were statistically significantly in favor of patellar resurfacing: sport/recreation, knee-related quality of life, pain, and symptoms. No statistically significant differences between the groups were observed with the Knee Society clinical rating system, with the Oxford knee score, and with visual analog scale (VAS) for patient satisfaction.

Interpretation — In the present study, the KOOS—but no other outcome measure used—indicated that patellar resurfacing may be beneficial in TKA.

The most effective treatment of the patello-femoral joint during total knee arthroplasty (TKA) remains controversial, and according to different national arthroplasty registries there is a remarkable variation between countries in whether the patella is resurfaced or not. In Norway and Sweden, only 2% of the TKAs have their patellas resurfaced (Norwegian Arthroplasty Registry 2014, Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Registry 2014). In Denmark, 76% of the patellas are resurfaced (Danish Knee Arthroplasty Registry 2014) and in Australia 54% are resurfaced (Australian National Joint Registry 2013). In the USA, 98% of TKAs registered in the Kaiser Permanente Registry were performed with patellar resurfacing (Paxton et al. 2011). Advocates of patellar resurfacing emphasize cost-effectiveness, a reduced number of reoperations, and less anterior knee pain (Helmy et al. 2008, Clements et al. 2010, Murray et al. 2014). Proponents of patellar retention claim that patellar resurfacing offers no advantages in functional outcome, reoperation rate, or total healthcare cost (Burnett et al. 2009, Group et al. 2009, Breeman et al. 2011), and that it is associated with more complications (Ogon et al. 2002).

Since 2011, 4 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing patellar resurfacing and non-resurfacing have been published (Fu et al. 2011, He et al. 2011, Pavlou et al. 2011, Chen et al. 2013). They all concluded that patellar resurfacing reduces the risk of reoperations. Concerning anterior knee pain and knee function, it was not possible to conclude whether patellar resurfacing is beneficial or not. In the meta-analyses, the assessment of knee function was based on 14 RCTs. In 11 of these studies, knee function was measured with the Knee Society clinical rating system (KSS), while the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) score was used in 2 studies and the Western Ontario and McMaster osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) in 1 study. However, in recent years, the discriminating capacity of these classical outcome measures has been questioned because of high ceiling effects (Hossain et al. 2011, Jenny et al. 2014, Hossain et al. 2015, Aunan et al. 2015). This may obscure differences between patients with high scores, and bias research results. New scoring systems have been developed in an attempt to avoid this problem (Roos and Toksvig-Larsen 2003, Behrend et al. 2012, Na et al. 2012, Noble et al. 2012, Hossain et al. 2013, Jenny et al. 2014).

We compared the functional outcome in osteoarthritic patients operated with TKA, with and without patellar resurfacing, using 4 different outcome measures. The primary outcome measure was the knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS) (Roos and Lohmander 2003) and secondary outcome measures were the KSS, the Oxford knee score, and patient satisfaction. These were recorded preoperatively and at follow-up after 1 year and 3 years. In addition, we calculated ceiling effects and interquartile ranges (IQRs) at 3 years for all outcome measures.

Patients and methods

Design

This was a single-center, randomized, double-blind study. It was conducted according to the CONSORT guidelines. All patients underwent surgery at Sykehuset Innlandet Hospital Trust, Lillehammer, Norway, which is a community teaching hospital that performs 50–70 primary TKAs per year. To ensure consistency in surgical technique, 1 surgeon (EA) was either operating or assisting at every operation.

Inclusion and exclusion

153 consecutive patients scheduled for primary TKA at our institution between November 2007 and March 2011 were assessed for eligibility for this study. Inclusion criteria were patients younger than 85 years with primary knee osteoarthritis. Exclusion criteria were knees with severe deformity of bone and/or ligaments that made them unsuitable for a standard cruciate-retaining prosthesis, patellar thickness less than 18 mm measured on calibrated digital radiographs, and isolated patello-femoral arthrosis. Also excluded were knees with secondary osteoarthritis (except for meniscal sequelae), previous surgery on the extensor mechanism, patients with a severe medical disability preventing them from climbing 1 level of stairs, and patients who were not able to fill out the patient-reported outcome measures (KOOS and Oxford knee score).

Randomization and blinding

Computerized random numbers in blocks with randomly selected block sizes were generated by a third party, and randomization of each knee was performed by the surgeon or the assistant immediately before the operation, through internet connection with the randomization server. The patients and the assessor of outcome (GN) were blind regarding the randomization allocation throughout the study.

Surgical technique

All knees were operated on through a standard midline incision and a medial parapatellar arthrotomy, using a cruciate-retaining, fixed-bearing prosthesis (NexGen; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) and a measured resection technique. All components were cemented. In order to create a neutral mechanical axis, the valgus angle of the femoral component was set at 5–8°, depending on the hip-knee-femoral shaft angle, as measured on preoperative standing hip-knee-ankle (HKA) radiographs (Ewald 1989). Ligament balancing was performed using the technique described by Whiteside and colleagues (Whiteside 1999, Whiteside et al. 2000). The patella was everted, and cartilage damage to the patella was graded according to the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) (Brittberg and Winalski 2003) and documented. Patellar resurfacing was performed with the onlay technique, removing bone of the same thickness as the prosthetic component, and accepting up to 1 mm over- or under-resection (measured with callipers before and after resection). In the non-resurfaced patellas, osteophytes were removed. Circumferential cauterization was not performed. In 2 cases, both in the non-resurfaced group, lateral release of the patellar retinaculum was performed. All operations were performed in a bloodless field, with a tourniquet on the proximal part of the thigh set between 250 and 350 mmHg depending on the patient’s blood pressure and soft tissues. No intra-articular anesthesia was used.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the KOOS (Roos and Toksvig-Larsen 2003). Secondary outcome measures were the KSS (Insall et al. 1989), the Oxford knee score (Dawson et al. 1998), and patient satisfaction measured on a visual analog scale (VAS). The primary and secondary outcome measures were recorded preoperatively and at 1 year and 3 years of follow-up. VAS was recorded at 1 year and 3 years. In addition, complications were recorded at all observation points.

The KOOS is a knee-specific, patient-reported outcome measure developed for more active patients. It has 5 separately-scored subscales for pain, other symptoms, activities of daily living (ADL), function in sport and recreation, and knee-related quality of life (QoL). Scores are transformed to a 0–100 scale, with 0 representing extreme knee problems and 100 representing no problems. The KOOS has been validated for use in TKA and has been shown to be a valid, reliable, and responsive measure (Roos and Toksvig-Larsen 2003).

The self-administered questionnaires (KOOS, Oxford knee score, and VAS score for patient satisfaction) were completed by the patient alone. In bilateral cases (28 knees), the 14 patients were encouraged to consider the knee under investigation when answering the questions. A physiotherapist who was blind as to the randomization group assessed the KSS scores. Range of motion was measured with a goniometer. Mechanical axes were measured on HKA radiographs preoperatively and at 1 year of follow-up, using the method described by Ewald (1989).

Finally, the ceiling effects—defined as the proportion of patients reaching the top score—and IQRs for all the outcome measures were calculated for the entire group.

Statistics

The minimal perceptible clinical improvement (MPCI) for KOOS has been suggested to be 8–10 points (Roos and Lohmander 2003). The power was set to 90%, the level of significance (p) at 5%, and the standard deviation at 16, resulting in a sample size of 55 knees in each treatment group. Allowing for some dropouts after 3 years of follow-up, we decided to include 130 knees.

Data were checked visually for normality based on histograms, using the findings in a recent publication by Fagerland and Sandvik (2009). Comparison of means was performed using the independent-samples t-test for normally distributed data and the Mann-Whitney U-test for skewed variables. Fisher’s exact test was used when analyzing categorical variables. When comparing the functional outcome variables in the 2 treatment groups from before surgery up to 3 years postoperatively, mixed-models analysis was used. The assumptions underlying this model were checked and found to be adequately met. No adjustments for multiple testing were performed and a significance level of 5% was used. Data analyses were performed with IBM SPSS 22 software.

Ethics

The protocol was approved by the Regional Committee of Research Ethics at the University of Oslo (REK: 1.2007.952) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT00553982). All the patients signed an informed consent form.

Results

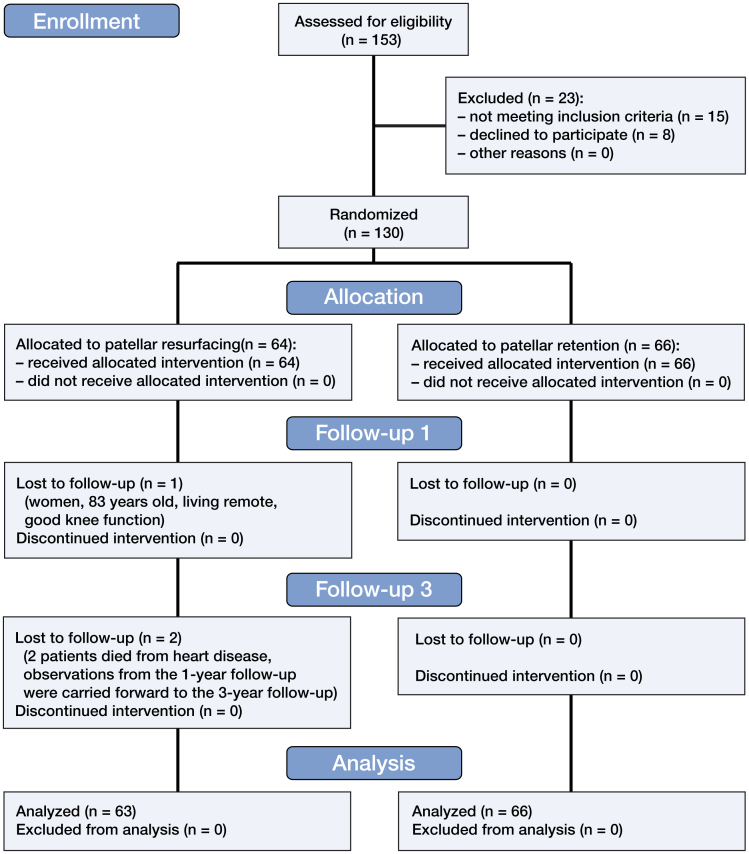

153 knees met the inclusion criteria and 23 of these knees were excluded (Figure 1). The reasons for exclusion were as follows (with number of patients in parentheses): severe deformity (1), isolated patello-femoral arthrosis (3), previous surgery on the extensor mechanism (6), severe medical disability (3), inability to fill out the patient-reported outcome measures (2), and refusal to participate in the study (8).

Figure 1.

CONSORT 2010 flow diagram.

An old woman declined follow-up visits after 3 months because she was living in a remote area and had not experienced any problems with her operated knee. Between the follow-up visits at 1 year and 3 years, 2 patients died from heart disease. For these 2 patients, the data from the 1-year follow-up were carried forward to the 3-year follow-up. As a result, 129 knees were investigated (in 73 women and 56 men). 14 patients underwent bilateral TKA. 66 knees were randomized to TKA without patellar resurfacing, and 63 knees to TKA with resurfacing. Baseline characteristics in the 2 groups were similar (Table 1). 1 patient who suffered from anterior knee pain was reoperated with patellar resurfacing 20 months after the index operation. In the final analysis, her data were kept in the original allocation group (intention to treat principle).

Table 1.

Baseline data for 129 knees

| Without patellar resurfacing (n = 66) | With patellar resurfacing (n = 63) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range) | 69 (42–82) | 70 (48–82) |

| Number of females | 38 | 35 |

| Mean BMI (range) | 29 (22–43) | 30 (20–38) |

| Mean ASA score (range) | 2.0 (1–3) | 2.0 (1–3) |

| Mean ICRS score (range) | 2.95 (1–4) | 2.92 (1–4) |

| Number of bilateral knees | 13 | 15 |

| Preoperative alignment | ||

| Varus, number of knees | 49 | 54 |

| Mean deformity (range) | 9.2° (2–21) | 8.6° (1–22) |

| Valgus, number of knees | 13 | 8 |

| Mean deformity (range) | 6.2° (2–13) | 5.9° (3–13) |

| Neutral, number of knees | 4 | 1 |

| Mean deformity | 0° | 0° |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists;

ICRS: International Cartilage Repair Society.

Functional outcome

The mean subscores for the primary outcome measure, the KOOS, were in favor of patellar resurfacing (Table 2). The greatest difference between the 2 groups at 3 years after surgery was seen in the subscore sport/recreation, with a 10-point difference between the groups (p = 0.01). In the other subscores, the differences were 8 points for knee-related QoL (p = 0.03), 6 points for pain (p = 0.02), and 5 points for symptoms (p = 0.04). In the subscore for ADL, there was a 5-point difference between the 2 groups, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.06).

Table 2.

Clinical outcome with preoperative, 1-year postoperative, and 3-year postoperative scores expressed as mean (SD). The preoperative scores were not significantly different between the treatment groups

| Without patellar resurfacing (n = 66) | With patellar resurfacing (n = 63) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KOOS | |||

| Pain, preop. | 42 (14) | 40 (18) | 0.02 |

| Pain, 1 year | 84 (18) | 90 (13) | |

| Pain, 3 years | 85 (18) | 91 (14) | |

| Symptoms, preop. | 50 (19) | 52 (17) | 0.04 |

| Symptoms, 1 year | 82 (16) | 86 (13) | |

| Symptoms, 3 years | 86 (13) | 90 (11) | |

| ADL, preop. | 45 (14) | 45 (19) | 0.06 |

| ADL, 1 year | 84 (17) | 89 (13) | |

| ADL, 3 years | 83 (18) | 88 (15) | |

| Sport/rec, preop. | 13 (13) | 13 (15) | 0.01 |

| Sport/rec, 1 year | 55 (25) | 64 (22) | |

| Sport/rec, 3 years | 57 (27) | 67 (27) | |

| QoL, preop. | 24 (12) | 24 (13) | 0.03 |

| QoL, 1 year | 78 (23) | 85 (17) | |

| QoL, 3 years | 77 (23) | 85 (19) | |

| KSS | |||

| Knee, preop. | 35 (15) | 34 (18) | 0.1 |

| Knee, 1 year | 84 (15) | 89 (12) | |

| Knee, 3 years | 90 (14) | 92 (9) | |

| Function, preop. | 65 (19) | 69 (20) | 1.0 |

| Function, 1 year | 87 (16) | 88 (17) | |

| Function, 3 years | 83 (21) | 83 (21) | |

| Oxford score | |||

| Preop. | 37 (6) | 37 (7) | 0.2 |

| 1 year | 19 (7) | 17 (6) | |

| 3 years | 18 (7) | 17 (6) | |

| Satisfaction (VAS), 1 year | 90 (21) | 95 (11) | 0.1b |

| Satisfaction (VAS), 3 years | 90 (16) | 92 (15) | 0.4b |

Mixed models including data from all time points.

Mann-Whitney U-test.

KOOS: knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (0–100); 100 is the best score.

KSS: Knee Society clinical rating system (0–100); 100 is the best score.

Oxford score: Oxford knee score (12–60); 12 is the best score.

ADL: activities of daily living; QoL: knee-related quality of life; preop.: preoperative (baseline) score.

No statistically significant differences between the 2 groups were observed for the secondary outcome measures (KSS knee score, KSS function score, Oxford knee score, and patient satisfaction) (Table 2).

4 complications occurred in 3 patients who were operated on with patellar resurfacing, and there were 3 complications in 3 patients who were operated on without (Table 3).

Table 3.

Complications

| Allocation group Complication | n | Treatment | VAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without patellar resurfacing | |||

| Patellar fracture with minimal displacement | 1 | None | 95 |

| Stiffness | 1 | AA and MUA | 50 |

| Partial quadriceps tendon rupture | 1 | Nonoperative treatment | 95 |

| With patellar resurfacing | |||

| Stiffness | 1 | AA and MUA | 10 |

| Lateral knee pain and stiffness | 1 | Neurolysis of the fibular nerve, AA and MUA | 80 |

| Hematogenous infection 2 years after the index operation | 1 | Soft tissue debridement | 79 |

VAS: Patient satisfaction at final follow-up with visual analog scale (0–100); 100 is the best score.

AA and MUA: arthroscopic arthrolysis and mobilization under anesthesia.

Ceiling effects

At 3 years of follow-up, the smallest ceiling effect was found for the sport/recreation subscore of the KOOS (6%). The highest ceiling effects were observed for the KSS function score (48%) and patient satisfaction (40%). More details of the outcome measures are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Detailed description of the different outcome scores at 3-year follow-up (n = 129)

| 3-year outcome | Range | Mean | SD | Ceiling effect, in % | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KOOS | |||||

| Pain | 31–100 | 88 | 16 | 36 | 18 |

| Symptoms | 32–100 | 88 | 12 | 19 | 14 |

| ADL | 31–100 | 86 | 17 | 24 | 23 |

| Sport/rec | 0–100 | 62 | 28 | 6 | 45 |

| QoL | 19–100 | 81 | 22 | 29 | 31 |

| KSS | |||||

| Knee score | 31–100 | 91 | 12 | 16 | 12 |

| Function score | −10 to 100 | 83 | 21 | 48 | 30 |

| Oxford score | 12–43 | 18 | 7 | 16 | 8 |

| Satisfaction (VAS) | 10–100 | 91 | 16 | 40 | 10 |

For abbreviations and explanations, see Table 2.

IQR: interquartile range.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized, double-blind trial to compare patellar resurfacing and non-resurfacing in TKA using KOOS as the primary outcome. The main finding was that resurfacing of the patella gave a statistically significantly better functional outcome. However, the clinical relevance of the differences between the groups is debatable. In contrast, the KSS knee score, the KSS function score, the Oxford knee score, and patient satisfaction did not show any statistically significant differences between the 2 groups.

A similar situation has been observed in several recent papers. Hossain et al. (2011) reported on a randomized controlled trial comparing 2 different prosthetic designs for TKA—by KSS, Oxford knee score, WOMAC score, SF-36, and a new score, the total knee function questionnaire (TKFQ). TKFQ is designed to assess demanding physical activities. The authors found that although there were statistically significant differences for range of motion, the TKFQ, and the physical component of SF-36, no significant differences were observed in KSS, total WOMAC, or Oxford knee score. They suggested that the lack of response in these 3 outcome measures could be attributable to ceiling effects, and that high-demand activities, such as sport and recreation, are not addressed. In a comparative study comparing patellar retention and patellar replacement in TKA, Van Hemert et al. (2009) found a statistically significant functional advantage for patients with resurfaced patella, using accelerometers fixed to the patients while they were performing a set of motion tasks mimicking daily activities, whereas no difference in KSS was found. Consequently, the authors recommended complementing the classical evaluation tools with objective functional tests. A recent study evaluating the influence of ligament laxity on functional outcome after TKA found a statistically significant association between ligament laxity and KOOS, but no such association was observed for the KSS, the Oxford knee score, or patient satisfaction. (Aunan et al. 2015).

Today’s patients tend to be younger and more physically active than in the past, and even in the elderly population aged between 60 and 80 years, a substantial proportion of patients participate in sports activity on a regular basis (Mayr et al. 2015). Functional assessment after TKA should therefore include measuring tools that take sports activities and other demanding activities into account. In a recent paper, Hossain et al. (2015) reviewed some of the current challenges using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) to evaluate TKA, and pointed out that ceiling effects, and lack of important considerations including ability in sports and recreational activities, may limit the power of PROMs to distinguish between treatments. These authors also highlighted alternative methods to improve the assessment of outcome: for example, more contemporary PROM-based instruments measuring high-demand function, and performance-based outcome measures.

Terwee et al. (2007) suggested that ceiling effects should be considered to be present in a health status measure if 15% or more of responders report the highest value. Many investigators have observed ceiling effects in the most commonly used outcome measures for TKA. Jenny et al. (2014) tested 100 patients who were operated on for TKA with more than 1 year of follow-up. They found that the ceiling effect for the KSS was 53%, and that it was 33% for the Oxford knee score. Na et al. (2012) studied 201 well-functioning knees in patients who had undergone primary TKA. The ceiling effect for the KSS knee score was 25%, that for the KSS function score was 43%, and that for the WOMAC score was 0%. Impellizzeri et al. (2011) documented profound ceiling effects from 41% to 67%, and modest floor effects from 10% to 19%, 6 months after TKA for the pain, stiffness, and function subscales in WOMAC. For the Oxford knee score, the authors found a 27% ceiling effect 6 months after the operation.

Giesinger et al. (2014) studied the comparative responsiveness of different outcome measures for TKA at different time intervals up to 2 years after surgery. They reported a decreasing responsiveness over time, especially beyond 1 year, and substantial ceiling effects for KSS and WOMAC scores 1 year after the index operation. The “forgotten joint score-12” (Behrend et al. 2012) was the most responsive of the tools assessed in their study.

We included KOOS, which is a more contemporary outcome measure developed for more active patients. In the sport/recreation subscore of the KOOS, patients were asked about difficulties when squatting, kneeling, running, jumping, and twisting. These are demanding activities, which may explain why only a few patients reach the “ceiling”. Thus, it is likely that this measure is better than others to distinguish between patients with high scores. It is noteworthy that the greatest effect size in our study was recorded for the sport/recreation score. Steinhoff et al. (2014) found higher responsiveness and lower ceiling effects in KOOS than in the KSS function score, and concluded that the KOOS should be used to measure TKA outcomes.

We found a striking dissimilarity in outcomes measured with the KOOS and with the classical outcome scores. The reason for this is unclear, but it is remarkable that the sport/recreation subscore in KOOS had the lowest ceiling effect (6.3%) and that very high ceiling effects were found in the KSS function score (48%) and VAS for patient satisfaction (40%). However, the KSS knee score and the Oxford knee score had near-acceptable ceiling effects. On the other hand, these items showed small IQRs and relatively small standard deviations, which might indicate clustering of data within a limited fraction of the outcome scales. In contrast, the KOOS subscores for pain, ADL, and QoL had higher standard deviations and IQRs, indicating less clustering of data and therefore higher discriminative capacity (Table 4). Finally, it should be considered that KSS is an assessor-reported outcome tool, and the KSS knee score is calculated from a combination based on pain score, flexion and extension scores, stability scores, and alignment scores.

In this study, the effect size at 3 years of follow-up in KOOS subscores was 10 points for sport/recreation, 8 points for QoL, 6 points for pain, and 5 points for symptoms and ADL. The minimal perceptible clinical improvement (MPCI) for KOOS has been suggested to be 8–10 points (Roos and Lohmander 2003); therefore, the clinical relevance of the observed effect sizes in our study is disputable. Nevertheless, the relatively small effect sizes observed for pain, symptoms, and ADL might be attributable to ceiling effects. Moreover, the exact definition of the MPCI remains controversial (Revicki et al. 2008).

14 patients in the present study underwent bilateral TKA, so the statistical independence between bilateral cases must be considered. However, the effect of bilateral cases depends on the study design (Park et al. 2010). Our study was randomized and the bilateral cases were equally distributed between the 2 groups (Table 1). Furthermore, in recent studies comparing outcome after arthroplasty, as in the present study, the authors have concluded that inclusion of bilateral cases does not alter the outcome (Bjorgul et al. 2011, Na et al. 2013).

A limitation of our study was that the results may not have been true for all prosthetic designs. We used a posterior cruciate-retaining design with fixed platform (Nexgen CR). Sacrificing the posterior cruciate ligament and introducing mobile bearings or other design alternatives might alter mechanics in the patello-femoral joint, and therefore the effect of patellar resurfacing may not be the same. The strengths of our study include the RCT design with blinding of patients and the outcome assessor, and the low number of dropouts. The wide inclusion criteria strengthened the generalizability of the study.

In summary, the primary outcome measure in our study (KOOS) indicated that patellar resurfacing may be beneficial for knee function in TKA, whereas the secondary, classical outcome measures—including KSS, Oxford knee score, and patient satisfaction recorded on a VAS—did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the groups. These findings indicate that the conclusions from earlier studies that used only classical outcome measures may be questionable, and that future investigations should include assessment tools with limited ceiling effects, which are responsive enough to discriminate between active patients performing demanding activities in their daily lives. In addition, patients undergoing TKA are heterogeneous; thus, future studies should be designed and powered to allow stratification of subjects into groups with different expectations and demands.

EA: conception, design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, and writing of manuscript. GN: assessment of all patients preoperatively and at follow-up. JCJ and TK: approval of the study protocol and contribution to critical revision of the final manuscript. LS: approval of the study protocol and performance of the mixed model analysis.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Aunan E, Kibsgard T J, Diep L M, Rohrl S M.. Intraoperative ligament laxity influences functional outcome 1 year after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23 (6): 1684-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australien National Joint Replacement Registry Annual Report 2013. https://aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au/nb/annual-reports-2013.

- Behrend H, Giesinger K, Giesinger J M, Kuster M S.. The “forgotten joint” as the the ultimate goal in joint arthroplasty: validation of a new patient-reported outome measure. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27: 430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorgul K, Novicoff W M, Brevig K, Ahlund O, Wiig M, Saleh K J.. Patients with bilateral procedures can be included in total hip arthroplasty research without biasing results. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (1): 120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeman S, Campbell M, Dakin H, Fiddian N, Fitzpatrick R, Grant A, et al. Patellar resurfacing in total knee replacement: five-year clinical and economic results of a large randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 (16): 1473-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittberg M, Winalski C S.. Evaluation of cartilage injuries and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-ASuppl2: 58-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett R S, Boone J L, Rosenzweig S D, Steger-May K, Barrack R L.. Patellar resurfacing compared with nonresurfacing in total knee arthroplasty. A concise follow-up of a randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91 (11): 2562-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Li G, Fu D, Yuan C, Zhang Q, Cai Z.. Patellar resurfacing versus nonresurfacing in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int Orthop 2013; 37 (6): 1075-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements W J, Miller L, Whitehouse S L, Graves S E, Ryan P, Crawford R W.. Early outcomes of patella resurfacing in total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (1): 108-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2014. www.dkar.dk. Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Annual Report 2014.

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A.. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998; 80 (1): 63-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald F C. The Knee Society total knee arthroplasty roentgenographic evaluation and scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; (248): 9-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerland M W, Sandvik L.. Performance of five two-sample location tests for skewed distributions with unequal variances. Contemp Clin Trials 2009; 30 (5): 490-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Wang G, Fu Q.. Patellar resurfacing in total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumato Arthrosc 2011; 19 (9): 1460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesinger K, Hamilton D F, Jost B, Holzner B, Giesinger J M.. Comparative responsiveness of outcome measures for total knee arthroplasty. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014; 22 (2): 184-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group K A T T, Johnston L, MacLennan G, McCormack K, Ramsay C, Walker A.. The Knee Arthroplasty Trial (KAT) design features, baseline characteristics, and two-year functional outcomes after alternative approaches to knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91 (1): 134-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J Y, Jiang L S, Dai L Y.. Is patellar resurfacing superior than nonresurfacing in total knee arthroplasty? A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Knee 2011; 18 (3): 137-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmy N, Anglin C, Greidanus N V, Masri B A.. To resurface or not to resurface the patella in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466 (11): 2775-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain F, Patel S, Rhee S J, Haddad F S.. Knee arthroplasty with a medially conforming ball-and-socket tibiofemoral articulation provides better function. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469 (1): 55-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain F S, Patel S, Fernandez M A, Konan S, Haddad F S.. A performance based patient outcome score for active patients following total knee arthroplasty. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013; 21 (1): 51-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain F S, Konan S, Patel S, Rodriguez-Merchan E C, Haddad F S.. The assessment of outcome after total knee arthroplasty: are we there yet? Bone Joint J 2015; 97-B (1): 3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impellizzeri F M, Mannion A F, Leunig M, Bizzini M, Naal F D.. Comparison of the reliability, responsiveness, and construct validity of 4 different questionnaires for evaluating outcomes after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (6): 861-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insall J N, Dorr L D, Scott R D, Scott W N.. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; (248): 13-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenny J Y, Louis P, Diesinger Y.. High Activity Arthroplasty Score has a lower ceiling effect than standard scores after knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29 (4): 719-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr H O, Reinhold M, Bernstein A, Suedkamp N P, Stoehr A.. Sports activity following total knee arthroplasty in patients older than 60 years. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30 (1): 46-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray D W, MacLennan G S, Breeman S, Dakin H A, Johnston L, Campbell M K, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different knee prostheses: the Knee Arthroplasty Trial (KAT). Health Tech Ass 2014; 18 (19): 1-235, vii-viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na S E, Ha C W, Lee C H.. A new high-flexion knee scoring system to eliminate the ceiling effect. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470 (2): 584-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na Y G, Kang Y G, Chang M J, Chang C B, Kim T K.. Must bilaterality be considered in statistical analyses of total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (6): 1970-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble P C, Scuderi G R, Brekke A C, Sikorskii A, Benjamin J B, Lonner J H, et al. Development of a new Knee Society scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470 (1): 20-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Arthroplasty Register Annual report 2014. http://www.haukeland.no/nrl/eng/default.htm.

- Ogon M, Hartig F, Bach C, Nogler M, Steingruber I, Biedermann R.. Patella resurfacing: no benefit for the long-term outcome of total knee arthroplasty. A 10- to 16.3-year follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002; 122 (4): 229-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M S, Kim S J, Chung C Y, Choi I H, Lee S H, Lee K M.. Statistical consideration for bilateral cases in orthopaedic research. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (8): 1732-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlou G, Meyer C, Leonidou A, As-Sultany M, West R, Tsiridis E.. Patellar resurfacing in total knee arthroplasty: does design matter? A meta-analysis of 7075 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 (14): 1301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton E W, Furnes O, Namba R S, Inacio M C, Fenstad A M, Havelin L I.. Comparison of the Norwegian knee arthroplasty register and a United States arthroplasty registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93Suppl3: 20-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revicki D, Hays R D, Cella D, Sloan J.. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61 (2): 102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos E M, Lohmander L S.. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003; 1: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos E M, Toksvig-Larsen S.. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) - validation and comparison to the WOMAC in total knee replacement. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003; 1 (1): 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff A K, Bugbee W D.. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score has higher responsiveness and lower ceiling effects than Knee Society Function Score after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; DOI 10.1007/s00167-014-3433-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register Annual report 2014. www.myknee.se.

- Terwee C B, Bot S D, de Boer M R, van der Windt D A, Knol D L, Dekker J, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60 (1): 34-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hemert W L, Senden R, Grimm B, Kester A D, van der Linde M J, Heyligers I C.. Patella retention versus replacement in total knee arthroplasty; functional and clinimetric aspects. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009; 129 (2): 259-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside L A. Selective ligament release in total knee arthroplasty of the knee in valgus. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999; 367: 130-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside L A, Saeki K, Mihalko W M.. Functional medial ligament balancing in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000; 380: 45-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]