Abstract

Background and purpose — Avascular necrosis of the femoral head (AVN) is a complication in treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). We evaluated the risk of AVN after early treatment in the von Rosen splint and measured the diameter of the ossific nucleus at 1 year of age.

Children and methods — All children born in Malmö, Sweden, undergo clinical screening for neonatal instability of the hip (NIH). We reviewed 1-year radiographs of all children treated early for NIH in our department from 2003 through 2010. The diameter of the ossific nucleus was measured, and signs of AVN were classified according to Kalamchi-MacEwen. Subsequent radiographs, taken for any reason, were reviewed and a local registry of diagnoses was used to identify subsequent AVN.

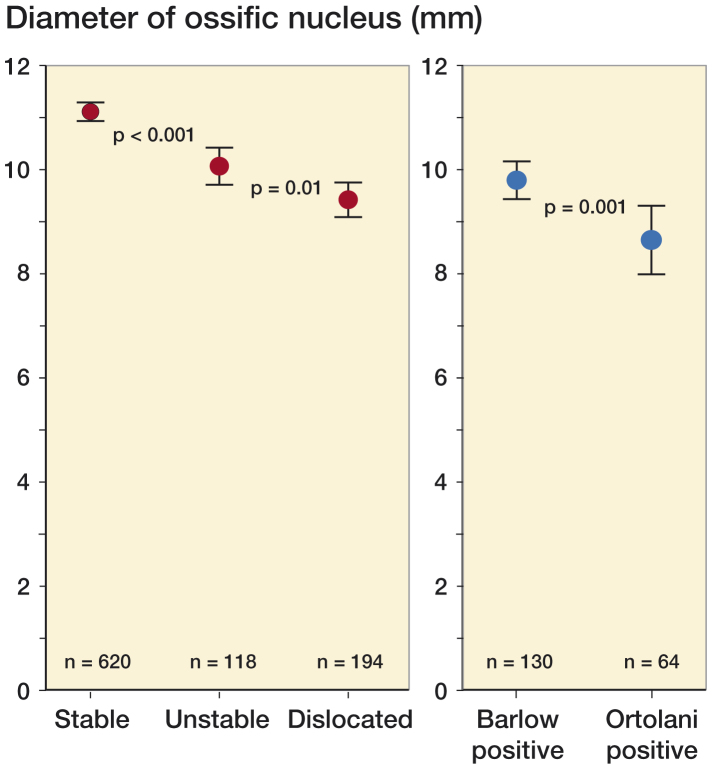

Results — 229 of 586 children referred because of suspected NIH received early treatment (age ≤ 1 week) for NIH during the study period. 2 of the 229 treated children (0.9%, 95% CI: 0.1–3.1) had grade-1 AVN. Both had spontaneous resolution and were asymptomatic during the observation time (6 and 8 years). 466 children met the inclusion criteria for measurement of the ossific nucleus. Neonatally dislocated hips had significantly smaller ossific nuclei than neonatally stable hips: mean 9.4 mm (95% CI: 9.1–9.8) vs. 11.1 mm (95% CI: 10.9–11.3) at 1 year (p < 0.001).

Interpretation — Early treatment with the von Rosen splint for NIH is safe regarding AVN. The ossification of the femoral head is slower in children with NIH than in untreated children with neonatally stable hips.

The term developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) covers a spectrum of diseases, including neonatal instability of the hip (NIH), acetabular dysplasia, and hip dislocation. DDH is a risk factor for osteoarthritis (Furnes et al. 2001, Engesaeter et al. 2008). In a report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, DDH accounted for 9% of all primary total hip replacements (THRs) in the period 1987–1999. In patients less than 60 years old, DDH accounted for 29% of THRs (Furnes et al. 2001). In Sweden, 1.9% of all THRs are due to DDH—and 15% of those in patients aged 50 years or younger (Garellick et al. 2012).

In longitudinal studies, screening for NIH and early treatment with abduction splinting has reduced the incidence of late-diagnosed dislocation (Palmén 1984, Dunn et al. 1985, Duppe and Danielsson 2002, Myers et al. 2009). There is, however, still some controversy regarding the best way to perform the screening process and how and when to start treatment if it is deemed necessary. Treatment complications, most notably avascular necrosis of the femoral head (AVN) (Kalamchi and MacEwen 1980) and a high rate of spontaneous resolution (Barlow 1962), are concerns that may lead to postponement of treatment in some centers.

A wide range in incidence of AVN has been reported for different abduction splints (MacKenzie 1972, Kruczynski 1996, Williams et al. 1999, Tegnander et al. 2001, Cashman et al. 2002, Nakamura et al. 2007, Myers et al. 2009).

Neonatally dislocated hips have delayed ossification of the femoral head (Bertol et al. 1982). It is unknown whether this delay in ossification is a consequence of the disease or the treatment, and whether its etiology is related to vascular disturbance.

The von Rosen splint was developed in our department in the 1950s and is still used (von Rosen 1956). In a small comparative study, it was superior to both the Pavlik harness and the Craig splint (Wilkinson et al. 2002). Treatment is normally started within 1 week of birth. The risk of late-diagnosed dislocation in our program was 0.07 of 1,000 live births in the period 1990–1999 (Duppe and Danielsson 2002).

The aim of this study was to determine the risk of AVN following early treatment of NIH with the von Rosen splint. Our hypothesis, based on clinical experience and a previous study in our institution (Fredensborg 1976), was that the risk of AVN would be lower than in previous publications that were cited in a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (Shipman et al. 2006). We also wanted to determine the size of the ossific nucleus at 1-year follow-up, comparing treated children to a reference group of untreated children. We hypothesized that the ossific nuclei would mineralize more slowly in treated children than in untreated children, and possibly also in relation to the degree of neonatal instability.

Patients and methods

All children born in Malmö are examined neonatally by a pediatrician using the Barlow (1962) and Ortolani (1976) tests. If this examination reveals a dislocated or a dislocatable hip, treatment is initiated immediately. If there is suspicion, but not certainty, of NIH, a dynamic sonography is performed within days (Dahlstrom et al. 1986). At sonography, a pediatric orthopedic surgeon performs the Barlow maneuver while a radiologist determines the extent of subluxation of the femoral head.

Children with a dislocated hip, i.e. who are Barlow- or Ortolani-positive, are treated for 12 weeks with a von Rosen splint. Children with an unstable hip, defined as ≥ 25% subluxation of the femoral head on sonography, are treated for 6 weeks. The splint is worn day and night and parents are discouraged from removing it. Once a week, the children are seen at the outpatient clinic for a bath and a physical examination by a specially trained nurse. Children with normal sonography are not treated. All referred children receive identical follow-up, including standard anterior-posterior radiographs of the pelvis at 3 and 12 months, regardless of whether or not they have been treated.

All children referred to our department on suspicion of NIH following the neonatal examination by the pediatrician from 2003 through 2010 were eligible for inclusion in this study. The hips were divided into groups according to the neonatal finding and treatment. After a clinical examination by an experienced orthopedic surgeon and ultrasound in cases with suspected instability, the hips were defined as “stable” (< 25% subluxation), “unstable” (≥ 25% subluxation), or “dislocated” (Barlow- or Ortolani-positive). Possible treatment was none (reference group), 6 weeks, or 12 weeks according to the criteria outlined above. Treatment was initiated at a mean and median age of 3 days.

Of the 586 children who were referred during the study period, 112 (19%) did not undergo dynamic sonography. 107 of these 112 children were treated for 12 weeks following a positive Barlow or Ortolani sign on physical examination. In 5 cases, a senior pediatric orthopedic surgeon decided on a 6-week treatment (2 cases that were judged to be clinically unstable but not Barlow-positive) or no treatment (3 cases that were judged to be stable) without the aid of sonography.

Radiographs at 12 months and any subsequent pelvic radiographs were reviewed for signs of AVN using the Kalamchi-MacEwen classification (Kalamchi and MacEwen 1980). Hospital files for all treated children were reviewed. Furthermore, the diagnosis registry in our catchment area from 2003 through 2013 was reviewed for diagnoses relating to AVN (ICD-10 codes M870, M911, and M918 (Socialstyrelsen 2011)).

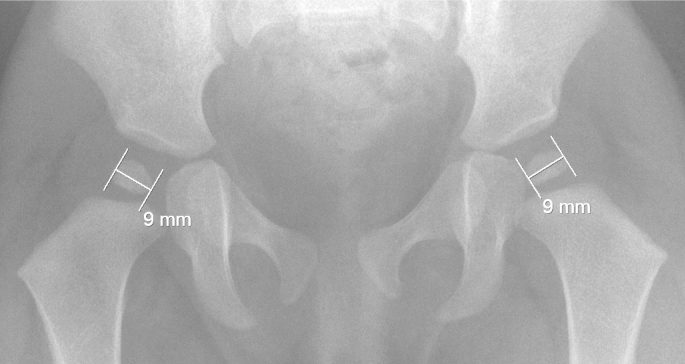

The maximum diameter of the ossific nucleus was measured on 12-month radiographs (Figure 1). Radiographs taken > 1 month from the first birthday were excluded from this measurement. Children diagnosed later than 7 days after birth were excluded from radiographic analysis. The intra-observer variability was tested by measuring the same 40 hips twice with a 2-month interval. The CV% was 1.9%. The systematic error was 0.004 mm.

Figure 1.

Measurement of the maximum diameter of the ossific nuclei.

Software and statistics

Radiographs were stored and viewed using Sectra PACS software (Sectra, Linköping, Sweden). Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0. For comparison of the diameter of the ossific nucleus between study groups, Student’s t-test was used. Any p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Ethics

The institutional review board approved the study (LU 2013/605).

Results

Epidemiology

During the study period, there were 34,308 live births in Malmö. 586 children (corresponding to 17 of 1,000 live births) were referred on suspicion of NIH. 6 children were treated for 12 weeks, despite being Barlow-negative. In statistical analyses, their hips were classified as belonging to the 12-week treatment group, but as “unstable” with regard to clinical findings. 1 child was treated for 1 week due to suspected bilateral dislocation, and was excluded from the analysis of ossific nucleus diameter. There were 134 girls (85%) among 158 children treated for 12 weeks, 64 girls (79%) among 81 treated for 6 weeks, and 228 girls (66%) among 346 untreated children. The incidence of NIH was 7 per 1,000 live births (Table).

Table. 1.

Comparison of the mean size of the ossific nucleus between study groups

| No. of hips (% of referrals) | Size of ossific nucleus, mm (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | |||

| 12 weeks | 292 (27) a | 9.7 (9.5–10.0) | < 0.001 b |

| 6 weeks | 138 (14) | 10.1 (9.8–10.4) | < 0.001 b |

| Reference group | 502 (59) | 11.3 (11.1–11.5) | |

| 12 weeks, stable hips | 67 | 10.4 (9.9–10.9) | 0.002 b |

| 6 weeks, stable hips | 51 | 10.3 (9.8–10.8) | 0.003 b |

| Clinical findings | |||

| Dislocated | 194 | 9.4 (9.1–9.8) | 0.01 c |

| Unstable | 118 | 10.1 (9.7–10.4) | |

| Stable | 620 | 11.1 (10.9–11.3) | < 0.001 c |

| Ortolani-positive | 64 | 8.7 (8.0–9.3) | 0.001 d |

| Barlow-positive | 130 | 9.8 (9.4–10.2) | |

| Sex | |||

| Girls, reference group | 342 | 11.6 (11.3–11.9) | < 0.001 e |

| Boys, reference group | 160 | 10.7 (10.2–11.3) | |

In total, neonatal instability of the hip (NIH) was left-sided in 103 (43%), right-sided in 31 (13%), and bilateral in 105 (44%) of 239 children. In the 152 children with dislocated hips, 60 (39%) were bilateral and 23 (15%) had an unstable contralateral hip. Note that the percentages given relate to all referrals, including those that did not meet inclusion criteria for analysis of the diameter of the ossific nucleus.

Comparison with reference group.

Comparison with unstable group.

Comparison with Barlow-positive.

Girls compared to boys in cases with bilaterally stable hips.

Avascular necrosis of the femoral head

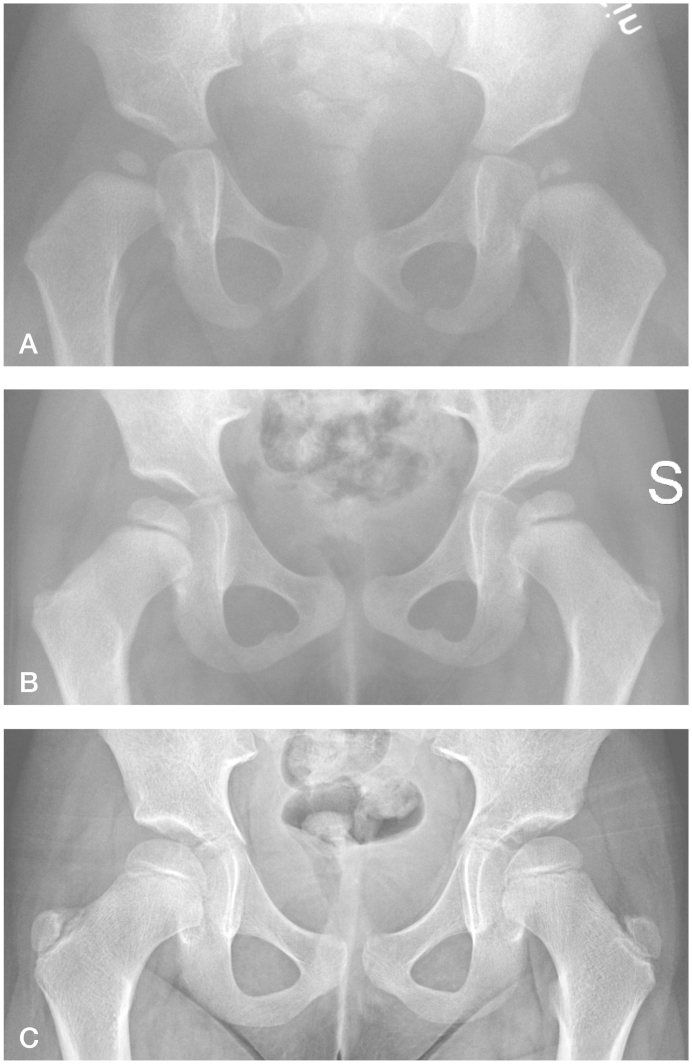

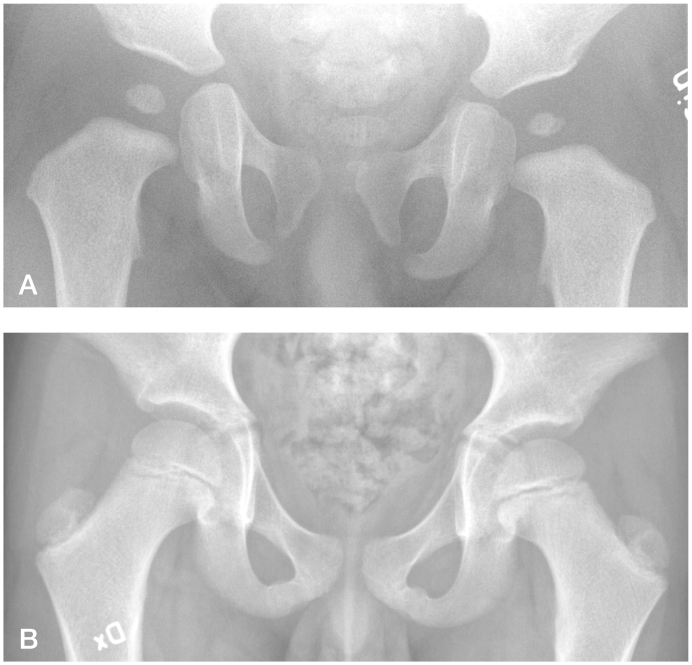

6 treated children were lost to follow-up at 1 year. Of the 234 remaining treated children, there were 2 children (0.9%, 95% CI: 0.1–3.1) with a radiographic grade-1 AVN (Figures 2 and 3). The radiographic signs of AVN resolved spontaneously and the children were asymptomatic during the observation period. The review of the diagnosis registry revealed 32 cases of Perthes disease. 1 of these patients had previously been treated for NIH. This was a boy who was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia at 2.5 years of age and who developed Perthes disease concurrently. No other child from the diagnosis registry had been treated previously for NIH.

Figure 2.

A. A girl with fragmentation of the left ossific nucleus (grade-1 AVN) at 12-month follow-up. Treatment had been initiated at 2 days of age for left-sided instability. B. Normal appearance of the femoral head at 3 years. C. Normal hip development at final check-up. The observation time was 5 years 7 months.

Figure 3.

A. A boy with mottled appearance of the left ossific nucleus (grade-1 AVN) at 12-month follow-up. Treatment had been initiated at 2 days of age for left-sided dislocation (Barlow-positive). B. Normal appearance of the femoral head at 8 years.

47 other treated children had further radiographs of the hips taken for various reasons. None of these radiographs showed signs of AVN. The mean observation time was 6.5 (2.8–11) years.

The size of the ossific nucleus

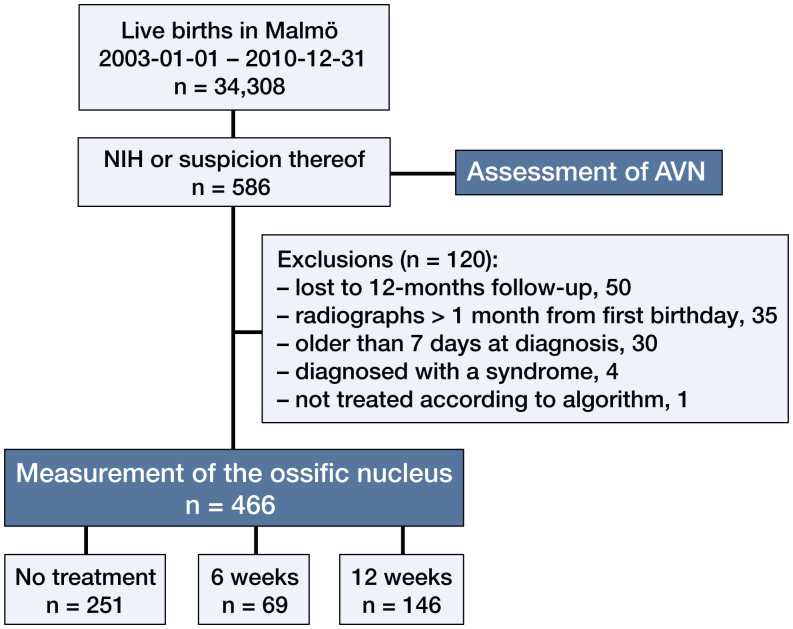

466 children met the inclusion criteria for the radiographic study (Figure 4). The results are listed in the Table . Hips treated for 12 or 6 weeks had smaller ossific nuclei at 12 months of age than the reference group. A higher degree of neonatal instability was associated with a smaller ossific nucleus at 12 months (Figure 5). In the reference group, girls had larger ossific nuclei than boys. In cases with unilateral dislocation or instability, the stable hips had smaller ossific nuclei than those in the reference group. 2 hips (1 treated girl and 1 boy in the reference group) had no visible ossific nucleus at the 12-month follow-up. Both had normal subsequent radiographs (they were followed to 1.5 and 3.5 years).

Figure 4.

Flow chart detailing inclusion of patients in the study. Assessment of AVN was performed by review of 1-year and subsequent radiographs (Kalamchi-MacEwen grading), hospital files, and a diagnosis registry to a mean observation time of 6.5 years.

Figure 5.

A higher degree of neonatal instability was associated with a smaller ossific nucleus at 12 months. Treatment differed between these groups (red dots).

Hips with a positive Ortolani test (i.e. dislocated in resting position) had smaller ossific nuclei than hips with a positive Barlow test (i.e. resting in the acetabulum but dislocatable) at 12 months. All these hips had 12 weeks of treatment (blue dots, subgroup analysis of dislocated hips). (n denotes the number of hips in each group. Error bars represent the 95% CI of the mean).

Late examination

30 referred children were excluded due to late examination (median 12.5 (8–34) days), 5 of whom were treated. None of these children had signs of AVN on their radiographs. The most common cause of late diagnosis was neonatal intensive care.

Additional treatment

8 treated children required additional treatment because of acetabular dysplasia on the 12-month radiograph (Pavlik harness and/or CAMP orthosis). They all developed radiographically normal hips without surgery, with follow-up to 2.5 (1.5–3.5) years.

Late-diagnosed dislocation

1 referred child who had been cleared at sonography, i.e. in the reference group, was excluded from radiographic analysis due to late-diagnosed dislocation of the left hip (detected at the routine radiography at 3 months).

Discussion

Avascular necrosis of the femoral head

The reported risk of AVN with the von Rosen splint, including the present study, ranges from 0.2% to 0.9% (Fredensborg and Nilsson 1976, Duppe and Danielsson 2002, Myers et al. 2009). In these studies, treatment was initiated within 1 week of birth. Williams et al. (1999) had no cases of AVN in 86 children treated with the Aberdeen splint, with treatment initiated in the maternity ward. Dunn et al. (1985) had no cases of AVN when the Aberdeen splint or the von Rosen splint was used in 445 children treated from the first week of life (with few exceptions). Also, the Frejka pillow has been shown to be safe regarding AVN if treatment is initiated neonatally. Tegnander et al. (2001) found 1 case of grade-3 AVN (0.9%) in 108 children treated with the Frejka pillow, and Finne et al. (2008) reported no cases in 298 treated children (but without describing how this was examined). Cashman et al. (2002) reported 1.6% AVN when the Pavlik harness was used in conjunction with neonatal screening, and cases presenting after 3 months age were excluded. Also, using a combination of the von Rosen Splint and the Pavlik harness, Bradley et al. (1987) reported a 1.8% risk of AVN when treatment was initiated within 6 weeks of birth.

In contrast to the above-mentioned studies on AVN following early treatment, studies reporting on treatment with the Pavlik harness (also including children with later treatment start) have found AVN in 7–11% of the children treated (Iwasaki 1983, Pap et al. 2006, Ohmori et al. 2009). In these studies, treatment was initiated up to 6–7 months from birth with mean ages of 3.2 months (Pap et al. 2006) and 4 months (Iwasaki 1983). Initiating treatment with the Pavlik harness at 4.5 (1–12) months, Nakamura et al. (2007) had AVN in 20% of the treated children, with 14% being Kalamchi-MacEwen grade 2–4.

Previous studies have linked earlier start of treatment to lower rates of AVN (Bradley et al. 1987, Kruczynski 1996), and also more severe AVN (Kalamchi and MacEwen 1980, Kruczynski 1996). In these studies, “early” start of treatment was at 0–6 months. 1 large study on the Pavlik harness found that the risk of AVN was lower if the treatment started within the first 3 months, but the authors did not report data to support this (Grill et al. 1988). Also, a higher degree of dislocation (Grill et al. 1988, Kruczynski 1996) and longer treatment time (Pap et al. 2006) have been reported to correspond to higher rates of AVN.

Due to the heterogeneity in study designs, we are unable to deduce from the literature whether splint design or age at treatment is the main determinant of AVN risk. However, our main finding that early treatment with the von Rosen splint is safe is supported in the literature.

In the present study, both cases of radiographic AVN were grade 1, which is associated with better outcome than grade 2–4 AVN (Kalamchi and MacEwen 1980, Agus et al. 2010). Both cases of AVN in our study affected the pathological hip, but studies on other splints have shown that the contralateral hip in unilateral cases may also be affected (Kalamchi and MacEwen 1980, Iwasaki 1983, Kokavec et al. 2006, Pap et al. 2006). However, these studies had median and mean ages at treatment start ranging from 3 to 11 months—as compared to 3 days in our study.

The Frejka pillow, now abandoned in most parts of Sweden, is associated with a higher rate of treatment failure than the von Rosen splint (Hansson et al. 1983, Heikkila 1988, Hinderaker et al. 1992). The von Rosen splint has also been found to be superior to the Pavlik harness and the Craig splint (Wilkinson et al. 2002). However, we are not aware of any randomized controlled trial comparing splints, either with regard to safety or efficacy.

The most common classification systems for AVN are those of Kalamchi and MacEwen (1980), Salter et al. (1969), Tönnis (1987), and Bucholz and Ogden (Ogden 1982). We used the Kalamchi-MacEwen classification, since we found the criteria to be detailed and applicable. Since the ossific nucleus is not visible in all children at 1 year, the Salter classification could be misleading in this age group (Salter et al. 1969, Williams et al. 1999).

The size of the ossific nucleus

As in previous studies, we found that the ossification of the femoral head is slower in treated children than in untreated children (Williams et al. 1999), in the less stable hip in cases with bilateral or unilateral instability (Fredensborg and Nilsson 1976), and in boys (MacKenzie 1972). We also found that stable hips in unilateral NIH had smaller ossific nuclei than bilaterally stable hips. It is difficult to deduce whether the slower ossification is mainly related to the treatment or to the disease. Stable hips in unilateral NIH have higher AI than controls at 1 year despite treatment (Wenger et al. 2013), suggesting that they are not entirely normal to begin with. Also, our finding that Ortolani-positive hips had smaller ossific nuclei than Barlow-positive hips supports the idea that slow ossification of the ossific head may be related to the disease per se.

The ossific nucleus is usually visible at 1 year of age (MacKenzie 1972). In our material, both children who were missing a visible ossific nucleus on the 12-month radiograph had normal subsequent radiographs taken. Williams et al. (1999) found the same.

Limitations

It may be argued that the observation time of 6.5 (2.8–11) years was short (Koizumi et al. 1996, Cashman et al. 2002, Nakamura et al. 2007, Agus et al. 2010, Firth et al. 2010). Kalamchi and MacEwen (1980), who described the classification used in our study based on a large sample of 119 hips with AVN, recommended follow-up to be performed until skeletal maturity in order not to miss “dormant” AVN or later-appearing physeal bars. However, the Kalamchi-MacEwen patients were 11 months old on average (range 1 month to 8 years) at the start of treatment, as compared to 3 (0–7) days in our study. In a 10- to 15-year follow-up study, Agus et al. (2010) made the diagnosis of AVN between 6 and 12 months after reduction in all 23 of their grade-1 AVN cases. Iwasaki (1983) made the same observation, that AVN was radiographically evident within the first year after reduction. Our 2 cases of grade-1 AVN were followed to 5 years 7 months and 8 years to verify normal development and to exclude later-appearing physeal bars. Previously, routine radiographic follow-up at 3 and 6 years was performed in our department, but this practice was discontinued since new cases of AVN or acetabular dysplasia were not found in children with normal radiographs at 1 year (Duppe and Danielsson 2002). It has also been reported from our program that the spherical index at 10 (8–16) years in children undergoing early treatment does not differ significantly from that in healthy controls (Fredensborg 1976). Based on the studies mentioned, the risk of later occurrence of AVN after early treatment, i.e. missed cases, should be small. However, the ideal study design to avoid missing later cases of AVN would have been a controlled prospective study with regular radiographic follow-up to skeletal maturity.

Children who moved to another region after the 12-month follow-up were not studied, which could also have led to missed cases of AVN. However, no additional cases of AVN were found through the diagnosis registry of ICD-10 codes, which also included children who had relocated to our region.

Strengths of the study

Although low rates of AVN following early treatment in the von Rosen splint have been reported previously, a recently published guideline document by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons stated that in studies on different splints “AVN rates were inadequately reported” (National Guideline, Clearinghouse 2014). This is important since, as expressed in a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in 2006, “the balance of benefits and harms of intervention is obscured by significant gaps in the available evidence” (Shipman et al. 2006). In the publications by Dunn et al. (1985) and Myers et al. (2009), there was no mention of AVN in the Methods sections, and Fredensborg and Nilsson (1976) only mentioned their findings briefly in the Discussion. The paper by Düppe and Danielsson (2002) clearly described the methods used but focused on many different aspects of screening. We present a study that was primarily designed to assess AVN, with strict inclusion criteria yielding a homogeneous study cohort, a high rate of follow-up, and a description of the method that allows reproduction. We used a diagnosis registry and reviewed all radiographs taken subsequently, to minimize the risk of missing (at least) any symptomatic cases of AVN.

Summary

Early treatment with the von Rosen splint for NIH is safe with regard to AVN; 2 (0.9%) of 229 children treated had asymptomatic Kalamchi-MacEwen grade-1 AVN that resolved spontaneously. NIH is associated with a slower ossification of the femoral head.

DW: study design, data analysis, and writing and revision of the manuscript; HS: analysis of radiographs, data analysis, and drafting and revision of the manuscript; HD: initiation of registry of NIH referrals and revision of the manuscript; CJT: study design and revision of the manuscript.

We thank Lars Gösta Danielsson who, together with one of the authors (HD), initiated the registration of NIH referrals.

This work was supported by grants from the Herman Järnhardt Fund, Skåne University Hospital Funds, and Lund University Funds.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Agus H, Omeroglu H, Bicimoglu A, Tumer Y.. Is Kalamchi and MacEwen Group I avascular necrosis of the femoral head harmless in developmental dysplasia of the hip? Hip Int 2010; 20 (2): 156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow T G. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1962; 44B (2): 292–301. [Google Scholar]

- Bertol P, Macnicol M F, Mitchell G P.. Radiographic features of neonatal congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1982; 64 (2): 176–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley J, Wetherill M, Benson M K.. Splintage for congenital dislocation of the hip. Is it safe and reliable? J Bone Joint Surg Br 1987; 69 (2): 257–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman J P, Round J, Taylor G, Clarke N M.. The natural history of developmental dysplasia of the hip after early supervised treatment in the Pavlik harness. A prospective, longitudinal follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84 (3): 418–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstrom H, Oberg L, Friberg S.. Sonography in congenital dislocation of the hip. Acta Orthop Scand 1986; 57 (5): 402–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn P M, Evans R E, Thearle M J, Griffiths H E, Witherow P J.. Congenital dislocation of the hip: early and late diagnosis and management compared. Arch Dis Child 1985; 60 (5): 407–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duppe H, Danielsson L G.. Screening of neonatal instability and of developmental dislocation of the hip. A survey of 132,601 living newborn infants between 1956 and 1999. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84 (6): 878–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engesaeter I O, Lie S A, Lehmann T G, Furnes O, Vollset S E, Engesaeter L B.. Neonatal hip instability and risk of total hip replacement in young adulthood: follow-up of 2,218,596 newborns from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (3): 321–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finne P H, Dalen I, Ikonomou N, Ulimoen G, Hansen T W.. Diagnosis of congenital hip dysplasia in the newborn. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (3): 313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth G B, Robertson A J, Schepers A, Fatti L.. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: open reduction as a risk factor for substantial osteonecrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (9): 2485–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredensborg N. The results of early treatment of typical congenital dislocation of the hip in Malmo. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1976; 58 (3): 272–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredensborg N, Nilsson B E.. Overdiagnosis of congenital dislocation of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1976; (119): 89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnes O, Lie S A, Espehaug B, Vollset S E, Engesaeter L B, Havelin L I.. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83 (4): 579–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garellick G K J, Rogmark C, Rolfson O, Herberts P. Svenska höftprotesregistret, Årsrapport 2011. Svenska höftprotesregistret, Årsrapport 2011. 2012. http://www.shpr.se/en/Publications/DocumentsReports.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Grill F, Bensahel H, Canadell J, Dungl P, Matasovic T, Vizkelety T.. The Pavlik harness in the treatment of congenital dislocating hip: report on a multicenter study of the European Paediatric Orthopaedic Society. J Pediatr Orthop 1988; 8 (1): 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson G, Nachemson A, Palmen K.. Screening of children with congenital dislocation of the hip joint on the maternity wards in Sweden. J Pediatr Orthop 1983; 3 (3): 271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila E. Comparison of the Frejka pillow and the von Rosen splint in treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop 1988; 8 (1): 20–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinderaker T, Rygh M, Uden A.. The von Rosen splint compared with the Frejka pillow. A study of 408 neonatally unstable hips. Acta Orthop Scand 1992; 63 (4): 389–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K. Treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip by the Pavlik harness. Mechanism of reduction and usage. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983; 65 (6): 760–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamchi A, MacEwen G D.. Avascular necrosis following treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980; 62 (6): 876–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi W, Moriya H, Tsuchiya K, Takeuchi T, Kamegaya M, Akita T.. Ludloff’s medial approach for open reduction of congenital dislocation of the hip. A 20-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996; 78 (6): 924–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokavec M, Makai F, Olos M, Bialik V.. Pavlik’s method: a retrospective study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2006; 126 (2): 73–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruczynski J. Avascular necrosis of the proximal femur in developmental dislocation of the hip. Incidence, risk factors, sequelae and MR imaging for diagnosis and prognosis. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1996; 268: 1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie I G. Congenital dislocation of the hip. The development of a regional service. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1972; 54 (1): 18–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers J, Hadlow S, Lynskey T.. The effectiveness of a programme for neonatal hip screening over a period of 40 years: a follow-up of the New Plymouth experience. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91 (2): 245–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura J, Kamegaya M, Saisu T, Someya M, Koizumi W, Moriya H.. Treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip using the Pavlik harness: long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007; 89 (2): 230–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Guideline C. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on detection and nonoperative management of pediatric developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants up to six months of age. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on detection and nonoperative management of pediatric developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants up to six months of age. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): Rockville MD; 2014. http://www.aaos.org/Research/guidelines/DDHGuidelineFINAL.pdf

- Ogden J A. Normal and abnormal circulation In: M O. Tachdjian. Congenital dislocation of the hip. C. Livingstone, New York: 1982; 59–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori T, Endo H, Mitani S, Minagawa H, Tetsunaga T, Ozaki T.. Radiographic prediction of the results of long-term treatment with the Pavlik harness for developmental dislocation of the hip. Acta Med Okayama 2009; 63 (3): 123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortolani M. Congenital hip dysplasia in the light of early and very early diagnosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1976; (119): 6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmén K. Prevention of congenital dislocation of the hip. Acta Orthop 1984; 55 (s208): 5–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pap K, Kiss S, Shisha T, Marton-Szucs G, Szoke G.. The incidence of avascular necrosis of the healthy, contralateral femoral head at the end of the use of Pavlik harness in unilateral hip dysplasia. Int Orthop 2006; 30 (5): 348–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter R B, Kostuik J, Dallas S.. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head as a complication of treatment for congenital dislocation of the hip in young children: a clinical and experimental investigation. Can J Surg 1969; 12 (1): 44–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman S, Helfand M, Moyer V, Yawn B. Screening for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip: A Systematic Literature Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen Internationell statistisk klassifikation av sjukdomar och relaterade hälsoproblem – Systematisk förteckning, svensk version 2011 (ICD-10-SE). Socialstyrelsen 2011. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/18172/2010-11-13.pdf

- Tegnander A, Holen K J, Anda S, Terjesen T.. Good results after treatment with the Frejka pillow for hip dysplasia in newborns: a 3-year to 6-year follow-up study. J Pediatr Orthop B 2001; 10 (3): 173–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tönnis D. Congenital Dysplasia and Dislocation of the Hip in Children and Adults. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg: 1987; 268–90. [Google Scholar]

- von Rosen S. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip joint. Acta Orthop Scand 1956; 26 (2): 136–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger D, Duppe H, Tiderius C J.. Acetabular dysplasia at the age of 1 year in children with neonatal instability of the hip. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (5): 483–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson A G, Sherlock D A, Murray G D.. The efficacy of the Pavlik harness, the Craig splint and the von Rosen splint in the management of neonatal dysplasia of the hip. A comparative study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84 (5): 716–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P R, Jones D A, Bishay M.. Avascular necrosis and the Aberdeen splint in developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1999; 81 (6): 1023–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]