Abstract

Faced with critical shortages of staff, long queues, and stigma at public health facilities in Livingstone, Zambia, persons who suffer from HIV/AIDS-related diseases use medicinal plants to manage skin infections, diarrhoea, sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, cough, malaria, and oral infections. In all, 94 medicinal plant species were used to manage HIV/AIDS-related diseases. Most remedies are prepared from plants of various families such as Combretaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, and Lamiaceae. More than two-thirds of the plants (mostly leaves and roots) are utilized to treat two or more diseases related to HIV infection. Eighteen plants, namely, Achyranthes aspera L., Lannea discolor (Sond.) Engl., Hyphaene petersiana Klotzsch ex Mart., Asparagus racemosus Willd., Capparis tomentosa Lam., Cleome hirta Oliv., Garcinia livingstonei T. Anderson, Euclea divinorum Hiern, Bridelia cathartica G. Bertol., Acacia nilotica Delile, Piliostigma thonningii (Schumach.) Milne-Redh., Dichrostachys cinerea (L.) Wight and Arn., Abrus precatorius L., Hoslundia opposita Vahl., Clerodendrum capitatum (Willd.) Schumach., Ficus sycomorus L., Ximenia americana L., and Ziziphus mucronata Willd., were used to treat four or more disease conditions. About 31% of the plants in this study were administered as monotherapies. Multiuse medicinal plants may contain broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents. However, since widely used plants easily succumb to the threats of overharvesting, they need special protocols and guidelines for their genetic conservation. There is still need to confirm the antimicrobial efficacies, pharmacological parameters, cytotoxicity, and active chemical ingredients of the discovered plants.

1. Introduction

Livingstone has the highest human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence level in Zambia. Although the average HIV prevalence rate in Zambia is about 13%, the HIV infection rate in Livingstone is about 25.3%, significantly higher than the national average [1]. During the period 1994–2002, Livingstone's HIV prevalence was stable at around 30% [2]. Located in Southern Province, Livingstone is the tourist capital of Zambia, home to the famous Victoria Falls. Therefore, many socioeconomic factors conspire to fuel the town's growing HIV epidemic. Transactional sex is very common in Livingstone, attributable to local or foreign tourists and high levels of poverty; receiving money or gifts for sex is the only means for vulnerable women to financially secure themselves and their families because other sources of income are not sufficient [3].

According to Byron et al. [4], women combine sex with the sale of material products to earn higher profits when they go to the market in town and end up contracting HIV. At 3.1%, women in Livingstone had the highest prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in Zambia [1]. Migrant labourers, especially sugar cane cutters from Mazabuka (Zambian town with the second highest HIV prevalence at 18.4%), are often blamed for being high-risk transmitters of HIV. In several sites in Livingstone, there are designated venues where people meet new sexual partners [2]. These sexual venues are linked to high partner turnover and due to major challenges in on-site condom availability, unprotected sex is common among guests [2]. Livingstone also has low rates of male circumcision at 11% [1].

In Livingstone, studies have reported sexual behaviours with a high potential for HIV transmission, yet there are few signs of HIV preventive interventions [3]. Despite the rollout of antiretroviral therapy (ART), Cataldo and others [5] stated that Zambian HIV-infected persons still seek treatment from traditional healers. Thus, although some western trained health care providers remain suspicious of traditional healers, most agree that traditional healers play an important and complementary role in the provision of effective HIV prevention or treatment [6]. Kaboru [7] also found that many biomedical health practitioners believe that Zambian traditional healers can help control HIV/AIDS.

Undoubtedly, several patients seek herbal remedies for conditions related to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) before seeking care at health centres [8]. This is because there are many deficiencies in the provision of biomedical services for STIs and HIV/AIDS in Zambia [7]. Unlike hospital staff with poor attitudes, traditional healers are also kinder and more compassionate to patients [7]. According to Ndulo et al. [9], traditional healers attend to patients with sexually transmitted infections (STIs), in both rural and urban areas; therefore, efforts should be made to promote cooperation between traditional and biomedical health care providers, so that treatment of patients and their partners could be improved. Traditional management that concurs with biomedical practices could thus be a starting point for discussion and cooperation.

Moreover, traditional healers have good knowledge of STIs [9]. Most of them use herbal preparations in the form of roots or powders administered orally to induce diarrhoea, vomiting, and diuresis. Traditional healers also correctly cite symptoms associated with STIs such as urethral or vaginal discharge. Therefore, Makasa et al. [10] observed that about 15% of patients with genital ulcer disease seek treatment from traditional healers. Although the use of traditional medicine is associated with nonadherence to ART, health care providers at hospitals should open lines of communication with traditional healers [11]. Makasa et al. [10] also noted the need to increase awareness among traditional healers that handle patients presenting with STIs and to refer certain cases to health facilities, especially when patients do not respond to traditional medicines.

Traditional healers far outnumber modern health care providers in Zambia where the Traditional Health Practitioners Association has over 40,000 members compared to a paltry 1,000 conventional medical doctors that are practicing nationwide [11]. There were 1,390 medical doctors practicing in Zambia; the doctor to population ratio was 1 to 17,589 instead of the World Health Organization recommended ration of 1 to 5,000 [12]. At the entrance of Zambia's University Teaching Hospital (UTH), a signpost reads “kindly take note that members of staff at UTH work under very critical shortage of manpower,” a stark reminder of the dearth of health staff and severe crisis facing the country. Given the glaring personnel shortages in many public health care facilities [13], involvement of traditional healers in the management of HIV/AIDS opportunistic diseases is a ubiquitous narrative.

Zambia is among the Sub-Saharan African countries with the most acute shortages of trained personnel in the health sector [14]. Predictably, use of traditional medicines was reported among 75% of inpatients at the UTH and among 68% of those seeking services for HIV counselling and testing [11]. Studies have shown that individuals that use traditional medicines are also associated with alcohol, have two or more sexual partners, engage in dry sex, and harbour STIs. Corollary, identification of persons who access traditional medicines may be an important target population for HIV prevention because many HIV risky behaviours are common among clients of traditional healers [11].

Besides, traditional healers are still consulted because they are deemed to provide client-centred and personalised health care that is customized to the needs and expectations of patients, paying special respect to social and spiritual matters [15]. Indeed, whilst the majority of HIV/AIDS patients that need treatment can access ART from local hospitals and health centres, several constraints of the ART programme compel many HIV-infected people to use traditional medicines to manage HIV/AIDS-related conditions [16]. Others use ethnomedicinal plants to offset side effects from ART [17]. The use of medicinal plants in Livingstone is also part of the medical pluralism whereby the introduction of allopathic medicines has not really dampened beliefs in indigenous diagnosis and therapeutic systems [18].

Even though there are some anecdotal reports regarding the traditional uses of ethnomedicinal plants to manage various diseases in Livingstone, knowledge on specific plant species used to manage HIV/AIDS-related diseases is still scanty and not well recorded. This paper is an inaugural and modest report on medicinal plants used in the management of HIV/AIDS opportunistic infections in Livingstone, Southern Province, Zambia. Documentation of putative anti-HIV plant species may help preserve this critical tacit indigenous knowledge resource. Plus, indigenous knowledge, coupled with a history of safe use and ethnopharmacological efficacy of medicinal flora, also presents a faster approach to discover new chemical compounds that may be developed into novel antiretroviral drugs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

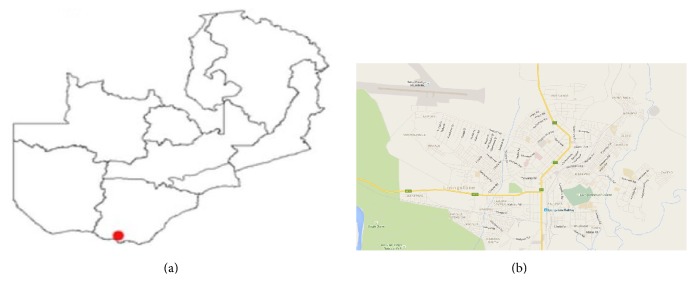

The study was carried out in Chibelenga, Burton, Dambwa, Hillcrest, Libuyu, Linda, Malota, Maramba, Ngwenya, and Zakeyo; these form the urban and rural settlements of Livingstone, provincial headquarters of Southern Province until 2012 (Figure 1). The geographical coordinates of Livingstone are 17°51′0′′ south, 25°52′0′′ east. The town is situated about 981 metres above sea level near the Victoria Falls on the Zambezi River close to the Zimbabwean border. Situated in agroecological region I, Livingstone has a humid subtropical climate. Its average annual rainfall is about 690–740 mm. The mean maximum temperature is high, 35°C in October, and the mean minimum temperature is low, 7°C in June. Recorded high (41.1°C) and low (−3.7°C) temperatures in November and June, respectively, have been documented. Rainy season occurs between November and March when it is wet, hot, and humid.

Figure 1.

(a) Map of Zambia showing the location of Livingstone. (b) Townships in Livingstone town.

According to the Holdridge life zones system of bioclimatic classification, Livingstone is situated in or near the subtropical dry forest biome. The terrain in Livingstone is well vegetated with over 1,000 plant species represented by riparian forests and woodlands, Kalahari woodlands, Colophospermum mopane (J. Kirk ex Benth.) J. Léonard woodlands, and deciduous woodlands mostly consisting of Brachystegia glaucescens Hutch. and Burtt Davy and the tall mahogany Entandrophragma caudatum Sprague. The vegetation is quite similar to that in adjoining Sesheke District as reported by Chinsembu [18] except for a few dominant plant species.

Between 1907 and 1935, Livingstone was the capital city of Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia. The town is named after David Livingstone who in 1840 as a young Scottish doctor and ordained minister sailed from Britain to the Cape to work as a medical evangelist with the London Missionary Society. In 1855, Dr. David Livingstone became the first European to see the Victoria Falls when he was taken there by Sekeletu, chief of the Subiya/Kololo people. Although contemporary life is a blend of values and traditions of more than 70 of Zambia's ethnically diverse people, the main tribes in Livingstone are the Tonga/Tokaleya and Lozi; many of them live in townships such as Maramba. Archaeological artifacts suggest the existence of the Tonga for at least 900 years in southern Zambia's Zambezi Valley. The Lozi migrated into Western Zambia from the Luba/Lunda Kingdom of Mwata Yamvwa in Zaire, present day Democratic Republic of the Congo.

After Zambia's independence in 1964, President Kenneth Kaunda's government built motor vehicle and radio assembly plants in Livingstone, attracting migrant workers. These manufacturing industries closed soon after President Frederick Chiluba became president of Zambia in 1991. In recent years, the town's economic fortunes have dwindled except for a slight influx of investment in the tourism sector characterized by the opening of modern hotel chains like Sun International. Commercial sex work is common among women; many of them are from neighbouring Zimbabwe where the socioeconomic situation remains dire.

2.2. Ethnobotanical Data Collection

Ethnobotanical data were collected using methods similar to that of [17–19]. Briefly, snowball sampling was applied during ethnobotanical surveys of thirty knowledge holders including 10 traditional healers that use plants to treat HIV/AIDS-related diseases. Before conducting interviews, the aim of the study was clearly explained and knowledge holders were asked for their consent. Then the knowledge holders were individually engaged in semistructured interviews supplemented with questionnaires. During the conversations, data on respondent characteristics and information related to medicinal uses of plants for the management of HIV/AIDS-related diseases were captured. All interviews were conducted in local languages, Tonga/Tokaleya, and Lozi. Research assistants acted as Tonga/Tokaleya/Lozi to English translators.

Data were collected during two stages consisting of primary and secondary samplings. The primary stage involved an exploratory and descriptive study of eight knowledge holders that manage HIV/AIDS-related infections. The focus of the exploratory study was to gain critical insights into the work of the knowledge holders, distil pertinent issues, and gauge whether a detailed ethnobotanical survey would be feasible. Knowledge holders were asked about the main symptoms of HIV/AIDS, their healing practices, and sources of ethnomedicinal knowledge. The following data in relation to the plants were also recorded: vernacular names (Tonga/Tokaleya/Lozi), plant habits, plant parts used, the HIV/AIDS-related conditions treated with the plants, and the modes of preparation and application of the plant remedies to the patient.

The secondary sampling stage was a follow-up and detailed descriptive study of 22 knowledge holders who verified prior ethnobotanical data obtained from others during the exploratory inquiry. To allow for triangulation of ethnomedicinal use, only plants mentioned by at least three knowledge holders in the descriptive study (for each disease condition) were eligible for documentation [20]. On-the-spot identification of familiar plant species was done in the field. Voucher numbers for plants were assigned and specimens for plants were collected in herbarium plant presses for identification and confirmation. Botanical names were verified using the International Plant Name Index (IPNI).

2.3. Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis of ethnobotanical data was done by calculating percentage frequencies, familiarity index F i, and factor informant consensus (F IC). The F i, a relative indicator of the familiarity of a plant species, is defined as the frequency a given plant species is mentioned as an ethnomedicine divided by the total number of knowledge holders interviewed in the study [21]. The F i was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where N a is the number of informants that mention a species as a medicine and N b is the total number of respondents.

The F IC was the number of use citations in each ailment category (N ur) minus the number of species used (N t), divided by the number of use citations in each category minus one [22]:

| (2) |

F IC values are low (near 0) if plants are chosen randomly or if informants do not exchange information about their use. Values are high (near 1) if there was a well-defined selection criterion among informants and/or if information was exchanged between informants. High F IC values are also obtained when only one or a few plant species are reportedly used by a high number of knowledge holders to treat a particular disease, and low F IC values imply that respondents disagree over which plant to use [23].

3. Results

Of all the thirty knowledge holders included in the study, only eight were female. This gender difference may be explained by the fact that male knowledge holders in the community were more comfortable to talk about STIs than female knowledge holders who face cultural restrictions when it comes to talking about matters related to sex, STIs, and HIV/AIDS. The average age of the healers was 48 years. About 70% of the knowledge holders received their medicinal plant knowledge from their older family members and the remainder from spiritual and supernatural powers such as ancestral spirits, dreams, and visions. Only six traditional healers had an apprentice under their tutelage; the rest did not train other people.

Medicobotanical data including the plants' scientific names, vernacular names, families, voucher numbers, habits, frequency indices, parts, HIV/AIDS-related diseases treated, modes of preparation, and application are described in Table 1. Overall, 94 plant species from 39 families were used by various knowledge holders to manage HIV/AIDS-related diseases in Livingstone, Southern Province, Zambia (Table 1). Their growth habits were as follows: almost half were trees (53.2%), about a quarter were shrubs (24.5%), and there were approximately equal proportions of climbers (11.7%) and herbs (10.6%).

Table 1.

Plants used to manage HIV/AIDS related diseases in Livingstone, Southern Province, Zambia.

| Family | Botanical name | Vernacular name | Growth form | Frequency index, voucher number | Diseases treated | Plant parts used, preparation, and mode of administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Barleria kirkii T. Anderson | Chavani | Herb | 13.3, L144 | HIV/AIDS | Leaf decoction is drank |

| Amaranthaceae | Achyranthes aspera L. | Tantajulo | Herb | 20.0, L186 | Cancer, pneumonia, cough, diarrhoea, fungal infections of the skin, genital warts | Root infusion or whole plant decoction is drank; paste of plant is applied to skin |

| Anacardiaceae | Lannea stuhlmannii (Engl.) Eyles | Mungangacha, Mucheche | Tree | 83.3, L245 | Gonorrhoea, syphilis, herpes zoster, herpes simplex, skin infections, HIV/AIDS |

Crushed leaves or roots are boiled in water, decoction is drank; stem bark decoction is used to wash affected skin |

| Anacardiaceae | Lannea discolor (Sond.) Engl. | Mungongwa | Tree | 50.0, L235 | Diarrhoea, gonorrhoea | Fruit pulp eaten to relieve diarrhoea; root infusion drank to relieve gonorrhoea |

| Annonaceae | Friesodielsia obovata (Benth.) Verdc. | Muchinga | Shrub | 20.0, L216 | Skin rashes | Pounded leaves rubbed into skin |

| Annonaceae | Artabotrys brachypetalus Benth. | Mulandabala | Climber | 13.3, L230 | Skin infections | Crushed leaves rubbed into skin |

| Apiaceae | Steganotaenia araliacea Hochst. | Mupelewa | Tree | 60.0, L113 | Headache | Root decoction is drank |

| Arecaceae | Hyphaene petersiana Klotzsch ex Mart. | Kakunka, Mapokwe | Tree | 20.0, L217 | Malaria, cough, tuberculosis, skin rashes, sores related to STIs | Palm fruit is eaten raw or boiled to treat malaria and cough; seeds are used to treat TB; sap is applied to heal skin rashes and STIs |

| Asclepiadaceae | Fockea angustifolia K. Schum. | Mutindika, Nanyama | Herb | 83.3, L210 | Cough | Tuber is eaten raw |

| Asparagaceae | Asparagus setaceus (Kunth) Jessop | Mutandamyoba | Climber | 50.0, L207 | Eczema | Whole plant is crushed and rubbed into affected skin |

| Asparagaceae | Sansevieria deserti N. E. Br. | Musombo, Mukonje | Herb | 13.3, L360 | Oral infections | Leaves are chewed and then spitted |

| Asparagaceae | Asparagus racemosus Willd. | Mutandamyoba, Ilutwa | Climber | 20.0, L433 | Pneumonia, cough, diarrhoea, syphilis | Whole plant is boiled; decoction is drank |

| Asteraceae | Vernonia amygdalina Delile | Musoboyo | Shrub | 83.3, L481 | Coughs, tuberculosis, malaria | Leaves are boiled; decoction is drank |

| Bignoniaceae | Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth. | Muzungula | Tree | 83.3, L485 | Syphilis, herpes simplex, diarrhoea, boils, colds, flu | Stem bark and leaves are boiled |

| Burseraceae | Commiphora mollis Engl. | Muntyokela | Tree | 50.0, L312 | Treats swollen pancreas in patients on antiretroviral therapy | Stem bark is crushed and boiled; decoction is drank |

| Capparaceae | Boscia salicifolia Oliv. | Mulaba, Kabombwe | Tree | 70.0, L406 | Syphilis, HIV/AIDS | Roots are ground and left in water; infusion is drank |

| Capparaceae | Capparis tomentosa Lam. | Chonswe | Shrub | 20.0, L329 | Syphilis rashes; HIV/AIDS; cryptococcal meningitis, oral candidiasis, herpes zoster, herpes simplex, chronic diarrhoea | Roots are crushed and boiled and decoction is drank; crushed leaves are applied to sores or soaked in water used to wash the mouth |

| Capparaceae | Cleome hirta Oliv. | Mulangazuba, Kalungukachisiungwa | Herb | 13.3, L303 | Pneumonia, tuberculosis, fungal infection of the skin, malaria | Leaf infusion is drunk |

| Celastraceae | Maytenus senegalensis (Lam.) Exell | Mukuba | Shrub | 50.0, LV235 | Tuberculosis | Leaves are crushed and soaked in water; infusion is drank |

| Celastraceae | Hippocratea africana Loes. ex Engl. | Mulele | Climber | 60.0, LV280 | Malaria | Root decoction is drunk |

| Chrysobalanaceae | Parinari curatellifolia Planch. ex Benth. | Mubulabula, Mula | Tree | 13.3, LV245 | Toothache, diarrhoea | Fruit eaten raw |

| Clusiaceae | Garcinia livingstonei T. Anderson | Mutungwa, Mukwanaga | Tree | 83.3, LV226 | Cryptococcal meningitis, herpes zoster, herpes simplex, skin rashes Tuberculosis chronic diarrhoea | Fruit eaten raw or in porridge |

| Combretaceae | Combretum collinum Fresen. | Mukunza, Mulamana | Tree | 43.3, LV187 | Chronic diarrhoea, tuberculosis, cough | Roots are crushed and soaked in water overnight; filtrate is drank |

| Combretaceae | Combretum imberbe Wawra | Mubimba, Muzwili | Tree | 83.3, LV238 | General STIs, tuberculosis | Stem bark is crushed and soaked in water overnight; filtrate is drank |

| Combretaceae | Combretum apiculatum Sond. | Mukalanga, Kalanga, Nkalanga | Tree | 50.0, LV220 | General STI syndromes; tuberculosis | Stem bark is crushed and soaked in water overnight; filtrate is drank |

| Combretaceae | Combretum elaeagnoides Klotzsch | Mukalanga, Mukupo | Tree | 30.0, L576 | Malaria, tuberculosis, diarrhoea | Fresh leaves are crushed and soaked in water overnight; filtrate is drank |

| Combretaceae | Combretum hereroense Schinz | Namazubo | Tree | 53.3, L437 | Gonorrhoea | Roots are crushed and soaked in water overnight; filtrate is drank |

| Combretaceae | Terminalia prunioides M. A. Lawson | Mutala, Mukonono, Mulumbu | Tree | 83.3, L247 | Gonorrhoea, syphilis, HIV/AIDS | Outer parts of roots are dried, crushed, and mixed with water overnight; infusion is drank |

| Combretaceae | Combretum mossambicense Engl. | Numinambelele, Silutombolwa, Mutombololo | Climber | 36.7, LV475 | Gonorrhoea, syphilis | Fresh leaves are crushed and soaked in water overnight; filtrate is taken orally |

| Combretaceae | Combretum paniculatum Vent. | Mutombolo | Shrub | 50.0, L322 | Malaria, diarrhoea | Leaves are pounded and soaked in water; infusion is drank |

| Connaraceae | Byrsocarpus orientalis Baill. | Kazingini | Shrub | 13.3, L521 | Skin abscesses and boils | Young stems are cut and boiled, and decoction is applied to skin |

| Dioscoreaceae | Dioscorea cochleari-apiculata De Wild. | Mpama | Climber | 13.3, L511 | Syphilitic sores, chancroid | Root decoction drank |

| Ebenaceae | Diospyros mespiliformis Hochst. ex A.DC. | Mchenja | Tree | 83.3, L109 | Malaria | Crushed roots are boiled; filtrate is drank |

| Ebenaceae | Diospyros quiloensis (Hiern) F. White | Musiaabwele | Tree | 50.0, LV339 | Gonorrhoea, syphilis, malaria | Crushed stem bark is boiled; filtrate is drank |

| Ebenaceae | Euclea divinorum Hiern | Munyansyabweli | Tree | 20.0, LV140 | Syphilis, gonorrhoea, genital herpes, oral candidiasis, abscesses, diarrhoea | Roots are ground and boiled in water and decoction is taken orally |

| Erythroxylaceae | Erythroxylum zambesiacum N. Robson | Mubalubalu | Tree | 16.7, LV277 | Malaria, headache | Roots are cut into small pieces and boiled, and decoction is administered orally |

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton gratissimus Burch. | Mungai, Kanunkila Mpati | Tree | 66.7, LV399 | Syphilis | Stem bark is boiled; decoction is drank and used to wash sores |

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton megalobotrys Müll. Arg. | Mutua, Mutuatua | Tree | 60.0, S149 | Gonorrhoea | Leaves are boiled and decoction is drank |

| Euphorbiaceae | Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia Pax | Mukunyu | Tree | 23.3, S108 | Diarrhoea, pneumonia | Stem bark decoction is drank |

| Euphorbiaceae | Bridelia cathartica G. Bertol. | Munyanyamenda | Shrub | 13.3, S154 | Oral infections, diarrhoea, gonorrhoea, malaria | Leaves and fruits are chewed raw to act as mouthwash; stem bark infusion is drank |

| Euphorbiaceae | Margaritaria discoidea (Baill.) G. L. Webster | Mulyankanga | Shrub | 16.7, S119 | Skin rashes and sores; headache | Stem bark |

| Euphorbiaceae | Phyllanthus reticulatus Lodd. | Mwichechele | Shrub | 26.7, S260 | Herpes simplex | Crushed leaves are rubbed to affected areas of skin |

| Fabaceae | Acacia albida Delile | Musangu, Muunga | Tree | 50.0, S100 | Syphilis sores, herpes zoster | Crushed leaves and stem bark are applied to heal sores |

| Fabaceae | Acacia nigrescens Oliv. | Mwabaa, Mukwena | Tree | 60.0, S78 | Herpes zoster | Leaves and stem bark are boiled, decoction used to |

| Fabaceae | Acacia polyacantha Willd. | Mumbu, Mukotokoto, Luntwele | Tree | 50.0, S63 | Gonorrhoea, herpes zoster | Leaves and stem bark are crushed and boiled; decoction is drank or used to wash affected skin |

| Fabaceae | Afzelia quanzensis Welw. | Mupapa, Mukamba | Tree | 76.7, S27 | General STIs | Leaves are pounded and soaked in water overnight and then drank |

| Fabaceae | Albizia amara (Roxb.) Boivin | Kankumbwila,Mukangola | Tree | 60.0, S44 | Gonorrhoea, diarrhoea | Stem bark infusion is drank |

| Fabaceae | Lonchocarpus capassa Rolfe | Mukololo | Tree | 13.3, S31 | Gonorrhoea, cough | Stem bark and leaves are mixed, crushed, soaked in water, and filtered and infusion is drank |

| Fabaceae | Peltophorum africanum Sond. | Muzenzenze | Tree | 83.3, K203 | General STIs, oral infections | Roots are soaked in water and infusion is drank to treat STIs; leaves are crushed and soaked in water; infusion is used to wash mouth |

| Fabaceae | Pterocarpus antunesii Harms | Mukambo | Tree | 26.7, K166 | Diarrhoea | Stem bark infusion is drank |

| Fabaceae | Acacia goetzei Harms | Mwaba | Tree | 46.7, K88 | Cough, pneumonia | Root decoction is drank |

| Fabaceae | Acacia nilotica Delile | Mukoka | Tree | 66.7, K56 | Tuberculosis, diarrhoea, gonorrhoea, dental caries | Twigs used as chewing sticks to treat dental caries |

| Fabaceae | Cassia abbreviata Oliv. | Mululwe | Tree | 83.3, K39 | Gonorrhoea, diarrhoea | Root infusion is drank |

| Fabaceae | Dalbergia melanoxylon Guill. & Perr. | Musonkomo | Shrub | 13.3, K17 | Diarrhoea | Root decoction is drank |

| Fabaceae | Piliostigma thonningii (Schumach.) Milne-Redh. | Musekese | Tree | 60.0, K12 | Coughs, skin rashes, gonorrhoea, syphilis | Stem bark and roots are boiled; decoction is drank to heal coughs and STIs; leaf infusion is used to wash infected skin |

| Fabaceae | Acacia ataxacantha DC. | Lubamfwa | Shrub | 50.0, K60 | Gonorrhoea, syphilis | Roots are boiled and decoction is drank |

| Fabaceae | Acacia schweinfurthii Brenan & Exell | Lubua, Mokoka | Shrub | 33.3, L34 | Gonorrhoea, syphilis | Roots, stem bark, and leaves are mixed, pounded, and soaked in water and infusion is drank |

| Fabaceae | Dichrostachys cinerea (L.) Wight & Arn. | Katenge, Mugee | Shrub | 66.7, L79 | Gonorrhoea, syphilis; oral candidiasis, and skin rashes | Stem bark is boiled and decoction is drank, used to wash oral cavity, or used to disinfect skin by washing |

| Fabaceae | Mimosa pigra L. | Muchabachaba, Sichatubabi | Shrubs | 83.3, L56 | Diarrhoea, genital ulcers, gonorrhoea | Leaves and small and young stems are dried, pounded into powder, mixed with water, and filtered and extract is drank or used to wash genital ulcers |

| Fabaceae | Sesbania sesban Britton | Mbelembele | Shrub | 13.3, L77 | Malaria | Roots are boiled and decoction is administered orally |

| Fabaceae | Indigofera colutea (Burm. f.) Merr. | Kapalupalu | Herb | 13.3, L59 | Diarrhoea | Whole plant is pounded, soaked in water overnight, and filtered, and infusion is drank to alleviate diarrhoea |

| Fabaceae | Abrus precatorius L. | Musolosolo | Climber | 60.0, KC280 | Gonorrhoea, syphilitic ulcers, genital herpes; oral candidiasis, ulcer boils | Whole plant is crushed, boiled in water, and filtered; decoction is drank; crushed leaves soaked in water and used to wash mouth and syphilitic ulcers |

| Fabaceae | Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC. | Muyuyu | Climber | 20.0, KC245 | Weight loss, lack of libido in men | Pods and beans are boiled and consumed for body building and to act as an aphrodisiac |

| Flacourtiaceae | Flacourtia indica (Burm. f.) Merr. | Mutumbula | Shrub | 13.3, KC350 | Diarrhoea | Leaves chewed raw |

| Flacourtiaceae | Oncoba spinosa Forssk. | Mukumbuzu | Shrub | 16.7, KC2 | Dysentery | Roots and fruits are boiled and decoction is drunk |

| Kirkiaceae | Kirkia acuminata Oliv. | Musanta, Muzumina | Tree | 13.3, KC18 | Diarrhoea | Stem bark infusion is drank |

| Lamiaceae | Vitex payos (Lour.) Merr. | Mfudu, Muyankonga | Tree | 30.0, KC36 | Coughs | Fruit eaten raw or leaves burnt and smoke inhaled as cough medicine |

| Lamiaceae | Hoslundia opposita Vahl | Musombwani | Shrub | 60.0, KC48 | Coughs, flu, fever, loss of libido in men; skin wounds | Roots are boiled and decoction is drunk; sugary fruits are eaten raw to boost libido; crushed leaves are rubbed into skin to heal wounds |

| Lamiaceae | Premna senensis Klotzsch | Mumpika | Shrub | 13.3, KC360 | Syphilitic sores, skin ulcers | Leaf infusions applied to sores |

| Lamiaceae | Vitex petersiana Klotzsch | Mufulibulimbo, Mukoma | Shrub | 23.3, KC312 | Gonorrhoea | Leaf decoction is drank to treat gonorrhoea; |

| Lamiaceae | Clerodendrum capitatum (Willd.) Schumach. | Shamanya | Herb | 60.0, L402 | Gonorrhoea, erectile dysfunction, pneumonia, diarrhoea | Leaf and root decoctions drunk |

| Loganiaceae | Strychnos potatorum L. f. | Musisilombe | Tree | 40.0, KC464 | Syphilis | Infusions of leaves are drank |

| Loganiaceae | Strychnos innocua Delile | Mutimi, Muhuluhulu, Mwabo | Tree | 20.0, KC216 | Gonorrhoea, sore throat | Eat fruit pulp |

| Malvaceae | Azanza garckeana (F. Hoffm.) Exell & Hillc. | Makole, Munego | Tree | 60.0, KC143 | Malaria | Eat raw fruit, cook, and eat as relish |

| Malvaceae | Sida alba L. | Mulyangombe, Babani | Shrub | 20.0, KC525 | Gonorrhoea | Roots and leaves are boiled; decoction is drank |

| Malvaceae | Hibiscus vitifolius L. | Mubaluba | Herb | Chronic diarrhoea | Leaves are boiled and filtered through wire sieve and decoction is drank | |

| Meliaceae | Khaya nyasica Stapf ex Baker f. | Mululu | Tree | 43.3, KC113 | Fever | Stem bark infusion is drank |

| Meliaceae | Trichilia emetica Vahl | Musikili | Tree | 56.7, KC217 | Fever, pneumonia; skin rashes | Root decoction is drunk; leaves rubbed onto skin |

| Menispermaceae | Cissampelos mucronata A. Rich. | Itende | Climber | 73.3, KC210 | Syphilis, chancroid | Whole plant is cut into small pieces and boiled and decoction is drank after filtering |

| Moraceae | Ficus capensis Hort. Berol. ex Kunth & C. D. Bouché | Mukuyu | Tree | 60.0, KC207 | Diarrhoea, tuberculosis, skin sores, genital warts | Fresh leaves are boiled in water and decoction is drank or used to wash warts and skin sores |

| Moraceae | Ficus sycomorus L. | Mukuyu | Tree | 76.7, KC360 | Cough, tuberculosis, periodontitis, and oral candidiasis | Fresh leaves are boiled in water and decoction is drank or used to wash the mouth |

| Myrtaceae | Syzygium cordatum Hochst. | Katope | Tree | 83.3, KC433 | Diarrhoea | Stem bark decoction is drunk |

| Myrtaceae | Syzygium guineense DC. | Mutoya, Katope | Tree | 83.3, KC481 | Abscesses, skin rashes, diarrhoea | Fruits eaten raw; stem decoction applied to affected skin |

| Olacaceae | Ximenia americana L. | Munchovwa, Muchonfwa | Tree | 83.3, KC318 | Candidiasis, malaria, throat infection, tonsillitis, gonorrhoea, diarrhoea, skin rashes | Roots, leaves, and fruits are crushed while fresh and mixed with water overnight and taken orally |

| Pedaliaceae | Sesamum angolense Welw. | Bwengo | Herb | 13.3, KC267 | Skin rashes | Leaves are crushed and used as soap to bath skin |

| Plumbaginaceae | Plumbago zeylanica L. | Sikalutenta | Shrub | 83.3, KC318 | Generally treats all STI symptoms | Root infusion is drank |

| Ranunculaceae | Clematis brachiata Ker Gawl. | Kalatongo | Climber | 20.0, KC354 | Coughs, headache, fever | Leaves are boiled and drunk as a tea; sometimes honey is added as a sweetener |

| Rhamnaceae | Berchemia discolor (Klotzsch) Hemsl. | Mwiiyi, Mwinji | Tree | 60.0, KC235 | Cough | Use fruit in porridge |

| Rhamnaceae | Ziziphus mauritiana Lam. | Masawu, Masawu | Tree | 40.0, KC226 | Gonorrhoea, syphilis | Fruit eaten raw, apply to wound, and put into porridge |

| Rhamnaceae | Ziziphus mucronata Willd. | Muchechete, Mwichechete | Tree | 83.3, KC144 | Gonorrhoea, syphilis, boils, pneumonia, cough | Root or leaf infusion is drank |

| Sapotaceae | Mimusops zeyheri Sond. | Mukalanjoni | Tree | 40.0, KC120 | Oral candidiasis | Fruit is eaten or root infusion is used as a mouthwash |

| Tiliaceae | Grewia flavescens Juss. | Namulomo, Mukunyukunyu | Shrub | 40.0, KC199 | Diarrhoea | Eat fruit pulp to relieve diarrhoea |

| Tiliaceae | Corchorus tridens L. | Delele | Herb | 13.3, KC101 | Syphilitic ulcers, chancroid | Root infusion drank or applied to ulcers |

| Vitaceae | Cissus quadrangularis L. | Mulungalunga, Chamulungelunge | Climber | 40.0, KC78 | Malaria, gonorrhoea | Sap is drank; whole plant infusion is drank |

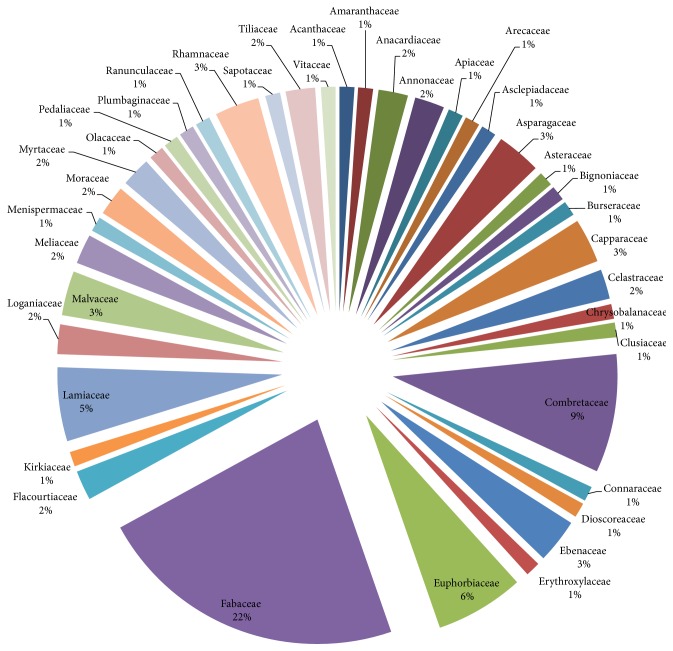

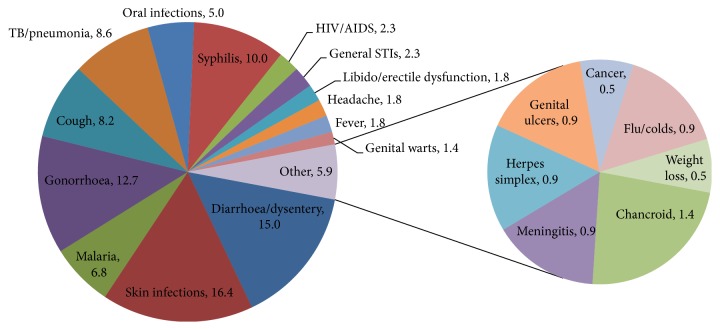

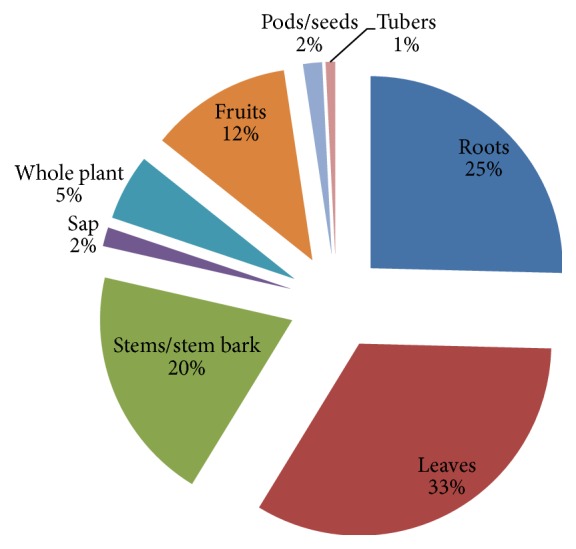

The most used families were Fabaceae (22%), Combretaceae (9%), Euphorbiaceae (6%), and Lamiaceae (5%) (Figure 2). The most plant parts used were leaves (33%), roots (25%), bark (22%), and stems/stem barks (20%) (Figure 3). Pods/seeds (2%) and tubers (1%) were least used. Plant exudates in the form of sap were also harvested from 2% of the plants. Figure 4 presents the proportions of plant species used to treat various HIV/AIDS-related disease conditions: skin infections (16.4%), diarrhoea/dysentery (15.0%), gonorrhoea (12.7%), syphilis (10.0%), tuberculosis (TB)/pneumonia (8.6%), cough (8.2%), malaria (6.8%), and oral infections (5.0%).

Figure 2.

Percentage use of plant families.

Figure 3.

Percentage use of plant parts.

Figure 4.

Proportions of plants used to treat different disease conditions.

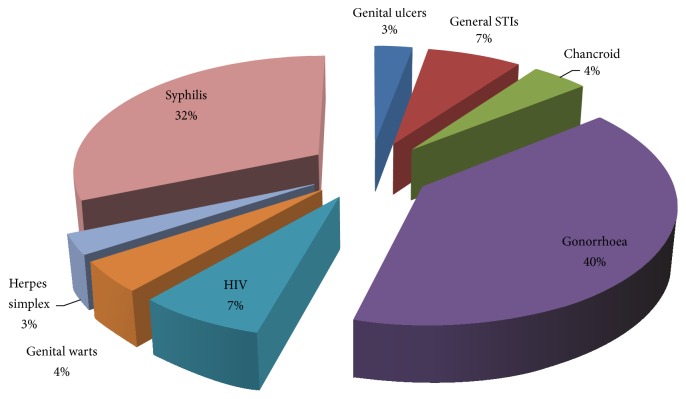

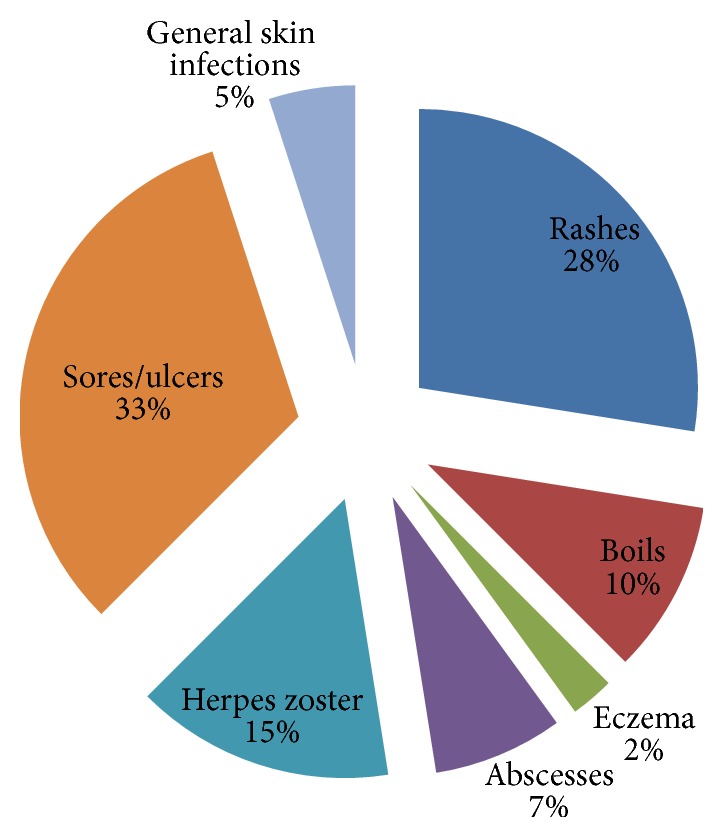

Figure 5 illustrates that of all the plants that were used to ameliorate skin conditions, most of them were used to manage skin sores or ulcers (33.0%), rashes (28.0%), herpes zoster (15.0%), boils (10.0%), and abscesses (7.0%). About 5% of all plants used on skin conditions treated general infections. Of all the ethnomedicinal plants used to manage STIs, the majority of them were used for gonorrhoea (40.0%), syphilis (32.0%), and HIV (7.0%) (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Percentage distribution of plants used to treat various skin conditions.

Figure 6.

Percentage distribution of plants used to treat various STIs.

Eighteen plants were utilized to treat four or more disease conditions: Achyranthes aspera L., Lannea discolor (Sond.) Engl., Hyphaene petersiana Klotzsch ex Mart., Asparagus racemosus Willd., Capparis tomentosa Lam., Cleome hirta Oliv., Garcinia livingstonei T. Anderson, Euclea divinorum Hiern, Bridelia cathartica G. Bertol., Acacia nilotica Delile, Piliostigma thonningii (Schumach.) Milne-Redh., Dichrostachys cinerea (L.) Wight and Arn., Abrus precatorius L., Hoslundia opposita Vahl, Clerodendrum capitatum (Willd.) Schumach., Ficus sycomorus L., Ximenia americana L., and Ziziphus mucronata Willd. Only 31% of the plants in this study were administered as monotherapies.

The F i values are given in Table 1. Informants were more familiar with the medicinal uses of the following fourteen most frequently used plants: Cassia abbreviata Oliv., Combretum imberbe Wawra, Diospyros mespiliformis Hochst. ex A.DC., Fockea angustifolia K. Schum., G. livingstonei, Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth., Mimosa pigra L., Syzygium cordatum Hochst., Syzygium guineense DC., Terminalia prunioides M. A. Lawson, Peltophorum africanum Sond., Plumbago zeylanica L., X. americana, and Z. mucronata. According to Table 2, F IC values for the various disease conditions show that consensus was high over plants used to treat malaria, oral infections, and fever/flu/colds/headache.

Table 2.

Informant consensus factor (F IC) for different ailments.

| Ailment | Number of species | Number of citations | F IC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhoea/dysentery | 33 | 120 | 0.73 |

| Skin infections | 36 | 108 | 0.67 |

| STIs | 70 | 210 | 0.67 |

| Malaria | 15 | 77 | 0.82 |

| TB/pneumonia | 19 | 68 | 0.73 |

| Oral infections | 11 | 55 | 0.81 |

| Cough | 18 | 71 | 0.76 |

| Fever/flu/colds/headache | 10 | 45 | 0.80 |

| Libido/erectile dysfunction | 4 | 12 | 0.73 |

| Meningitis | 2 | 6 | 0.80 |

| Weight loss | 1 | 4 | 1.00 |

| Cancer | 1 | 4 | 1.00 |

4. Discussion

The highest proportion of plants in Livingstone was used to manage skin diseases, probably because they contain antimicrobial agents. A similar scenario was obtained in Sesheke (Zambia) and Rundu (Namibia). This speaks to the fact that skin infections are quite common during HIV infection. Many of the plants for skin diseases in Livingstone were used to manage skin infections in other geographical settings. For instance, Afolayan et al. [24] and Hedimbi and Chinsembu [25] documented the use of Asparagus species in the treatment of eczema in South Africa and Namibia, respectively. Friesodielsia obovata was used to treat skin infections in the Zambezi Region of Namibia [26].

Capparis tomentosa is also used to treat skin rashes and herpes zoster in Katima Mulilo, Namibia [17]. Many Acacia species are also used to manage skin conditions in Southern Africa [27]. Kenyans use Trichilia emetica and Syzygium guineense to treat skin cancers [28]. Leaves of one of the fig trees, Ficus capensis, were also a remedy for skin sores. Skin diseases lie at the centre of both Christian and Islamic faiths. Indeed, the use of figs to treat skin diseases such as boils is well documented in the Bible; see 2 Kings 20:7 where a poultice of common figs (Ficus sp.) was applied to heal boils.

Lannea stuhlmannii was used to treat skin infections in Livingstone. The Lannea species were used to treat skin diseases in South Africa [27]. Chinsembu and Hedimbi [17] found that Lannea zastrowina was used as a remedy for skin rashes and herpes zoster in Katima Mulilo in Namibia. Elsewhere, Lannea species were known to have antibacterial [29] and antiviral [30] properties, making them good candidates for treating microbial skin infections.

The plant Kigelia africana, used in this study to manage boils, was also used in Ghana to treat skin ailments including fungal infections, boils, psoriasis and eczema, leprosy, syphilis, and cancer [31]. The plant is known to contain iridoids which confer antibacterial properties [32]. Euclea divinorum and Ximenia americana, skin remedies described in this study, were also documented as skin treatments by [27] in South Africa. Plants such as Acacia, Kigelia africana, and Maytenus senegalensis are used as ethnomedicine for skin infections [33].

Some of the plant taxa used to manage diarrhoea in this study have also been reported to treat diarrhoea in other studies. Achyranthes aspera L. is a known treatment for diarrhoea [34, 35]; Asparagus racemosus roots have been used traditionally in Ayurveda for the treatment of diarrhoea and dysentery [33]; K. africana is a known antidiarrhoeal remedy and Parinari curatellifolia attenuates diarrhoea [36, 37].

Oncoba spinosa is an antidote for diarrhoea in Ethiopia [38]. Studies in Nigeria showed that extracts of Acacia nilotica produced comparable antidiarrhoeal activity similar to loperamide, a drug widely employed against diarrhoeal disorders [39]. Garcinia livingstonei was a remedy for diarrhoea in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa [40]; a decoction from the roots Combretum collinum was drunk for the treatment of diarrhoea [41]; Bridelia cathartica, Flacourtia indica, and Kirkia acuminata are prescriptions for diarrhoea in Zimbabwe [42, 43].

Members of the genus Grewia were used as a remedy for diarrhoea in Katima Mulilo [17] and Mimosa pigra was harvested to treat diarrhoea in Rundu [18]. Rakotomalala et al. [44] showed that M. pigra is rich in tryptophan, quercetin, and several phenolic compounds which confer antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Dalbergia melanoxylon has antidiarrhoeal effects [45].

Studies in Tanzania found that Indigofera colutea has antimicrobial activities and hence can be used to manage diarrhoea. Ficus capensis has vibriocidal and antiamoebic actions [46] and therefore is used to treat diarrhoea in Lubumbashi in the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo [47]. An anti-inflammatory bioflavonoid, gossypin, is found in Hibiscus vitifolius, a good remedy for diarrhoea [48]. Syzygium cordatum Hochst, due to its antibacterial properties, is an antidiarrhoeal remedy in Swaziland [49].

Many plants used to treat STIs in Livingstone were also used to manage STIs in Sesheke District, Zambia [18]. This is because inhabitants of both Livingstone and Sesheke mainly belong to the Lozi ethnic group. Therefore, they tap into a similar ancestral vein of indigenous knowledge. For example, in both Livingstone and Sesheke, gonorrhoea was treated with a couple of species of the genera Lannea, Combretum, Terminalia, Diospyros, Ximenia, and Ziziphus.

The Lozi people of Sesheke used 52 plant species in 25 families and 43 genera to treat gonorrhoea, syphilis, chancroid, chlamydia, genital herpes, and anogenital warts. STIs were frequently managed using the following plants: Terminalia sericea, Strychnos cocculoides, Ximenia caffra, Cassia abbreviata, Cassia occidentalis, Combretum hereroense, Combretum imberbe, Dichrostachys cinerea, Boscia albitrunca, Momordica balsamina, and Peltophorum africanum [18].

Ziziphus mauritiana, also known as Masau in Nyanja, is a wild fruit plant very rich in vitamin C. It contains 20 to 30% sugar, up to 2.5% protein, and 12.8% carbohydrates. The plant is a remedy for STIs because aqueous extracts and powders have broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. Its extracts are also used as a dressing to prevent bacterial infections and to aid in wound healing during male circumcision among the Lunda and Luvale people of Zambia [50]. The anti-HIV plant Ximenia americana contains oleic, hexacos-17-enoic (ximenic), linoleic, linolenic, and stearic acids. Its oil consists of very long chain fatty acids with up to 40 carbon atoms. X. americana is also used to manage STIs including gonorrhoea in Western Province, Zambia [18].

Euclea divinorum, a treatment for gonorrhoea in Livingstone, had antibacterial action with minimum inhibitory concentration values ranging from 25.0 mg/mL to 0.8 mg/mL and moderate cytotoxicity [51]. Ximenia americana and Croton megalobotrys, known as Mtswanza and Muchape (resp.) among the Kore-kore people of Chiawa District in Zambia, are also prepared as formulations for gonorrhoea [52].

Many species of Acacia are used to treat TB and pneumonia, owing to their antibacterial and anti-HIV activities [53, 54]. Acacia nilotica leaf, bark and root ethanol, or ethyl acetate extracts were active against Mycobacterium aurum, MIC = 0.195–1.56 mg/mL [55]. Combretum imberbe contains pentacyclic triterpenes, with MIC = 1.56–25 μg/mL against Mycobacterium fortuitum [55]. Maytenus senegalensis is a known anti-HIV and antimycobacterial treatment in Uganda and Tanzania [56, 57]. A Cleome species was used to treat TB in Livingstone. In South Africa, Hurinanthan [58] found that Cleome monophylla leaf extract had anti-HIV-1 reverse transcriptase activity. Cleome gynandra is a treatment for chancroid in Sesheke and a remedy for malaria in other parts of Zambia [17, 18].

Studies show that HIV/AIDS is associated with low libido in men, sometimes because of depression and poor moods [59, 60]. Men on ART were also associated with sexual dysfunction [61]. Unsurprisingly, loss of libido and erectile dysfunction in men were commonly associated with HIV infection in Livingstone. HIV-infected men suffering from loss of libido and erectile dysfunction often used herbs to restore their sexual prowess. Mucuna pruriens, a plant with antibacterial activity [62], is also known to improve fertility, sexual behaviour, and erectile function in animals [63–65]. Extracts of the plant Hoslundia opposita corrected erectile dysfunction in Livingstone men living with HIV infection and were also commonly used to manage noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus in Tanzania [66]. Erectile dysfunction and loss of libido are common in men with diabetes [67].

5. Conclusions

In Livingstone, Southern Province, Zambia, traditional healers and other knowledge holders use 94 medicinal plant species to manage HIV/AIDS-related diseases mainly skin infections, diarrhoea, STIs, TB, cough, malaria, and oral infections. Majority of the plants belonged to the families Fabaceae and Combretaceae. Most plant leaves and roots were utilized to treat two or more disease conditions related to HIV infection. These multiuse medicinal plants probably contain broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents but may also face the threats of overharvesting, thus requiring special regulations for their genetic conservation.

The indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants is quite consistent especially for managing common HIV/AIDS-related conditions such as malaria, oral infections, fever, flu, colds, and headache. Although the results of this study are consistent with ethnobotanical and antimicrobial data from many reports in the literature, further studies are needed to confirm the antimicrobial efficacies, pharmacological, cytotoxicity, and active chemical ingredients of the plants.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to all respondents who provided critical data and to all the research assistants who helped with data collection.

Competing Interests

The author has no conflict of interests or competing interests to declare. Professor Chinsembu is the chair of the steering committee on the scientific validation of plants for HIV/AIDS treatment in Namibia.

References

- 1.Central Statistical Office (CSO) Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2013-14. Rockville, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health, Lusaka, Zambia; ICF International; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandøy I. F., Zyaambo C., Michelo C., Fylkesnes K. Targeting condom distribution at high risk places increases condom utilization-evidence from an intervention study in Livingstone, Zambia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1, article 10) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandøy I. F., Siziya S., Fylkesnes K. Lost opportunities in HIV prevention: programmes miss places where exposures are highest. BMC Public Health. 2008;8, article 31(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byron E., Gillespie S., Hamazakaza P. Local Perceptions of HIV Risk and Prevention in Southern Zambia. Washington, DC, USA: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cataldo F., Kielmann K., Kielmann T., Mburu G., Musheke M. ‘Deep down in their heart, they wish they could be given some incentives’: a qualitative study on the changing roles and relations of care among home-based caregivers in Zambia. BMC Health Services Research. 2015;15, article 36:10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0685-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnett A., Baggaley R., Ndovi-MacMillan M., Sulwe J., Hang'Omba B., Bennett J. Caring for people with HIV in Zambia: are traditional healers and formal health workers willing to work together? AIDS Care. 1999;11(4):481–491. doi: 10.1080/09540129947875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaboru B. B. The Interface between Biomedical and Traditional Health Practitioners in STI and HIV/AIDS Care: A Study on Intersectoral Collaboration in Zambia. Institutionen för folkhälsovetenskap/Department of Public Health Sciences; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munthali S. C. Acceptability of antiretroviral drugs among adults living in Chawama, Lusakaa [MPH dissertation] Lusaka, Zambia: University of Zambia; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ndulo J., Faxelid E., Krantz I. Traditional healers in Zambia and their care for patients with urethral/vaginal discharge. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2001;7(5):529–536. doi: 10.1089/10755530152639756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makasa M., Fylkesnes K., Sandøy I. F. Risk factors, healthcare-seeking and sexual behaviour among patients with genital ulcers in Zambia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1, article 407) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banda Y., Chapman V., Goldenberg R. L., et al. Use of traditional medicine among pregnant women in Lusaka, Zambia. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2007;13(1):123–128. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.6225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowa K., Goma F., Yikona J. I. N. M., Mulla Y. F., Banda S. S. A review of outcome of postgraduate medical training in Zambia. Medical Journal of Zambia. 2008;35(3):88–93. doi: 10.4314/mjz.v35i3.46524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makasa E. The Human Resource crisis in the Zambian Health Sector—a discussion paper. Medical Journal of Zambia. 2008;35(3) doi: 10.4314/mjz.v35i3.46522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tropical Health and Education Trust. Mapping of health links in the Zambian health services and associated academic institutions under the Ministry of Health. Report submitted to the Executive Director and Permanent Secretary, 2007, http://www.zuhwa.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/2007-THET-Zambia-MoH-Health-Links-Mapping.pdf.

- 15.King R., Homsy J. Involving traditional healers in AIDS education and counselling in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. AIDS. 1997;11(2):S217–S225. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199702000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chinsembu K. C. Model and experiences of initiating collaboration with traditional healers in validation of ethnomedicines for HIV/AIDS in Namibia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2009;5, article 30 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chinsembu K. C., Hedimbi M. An ethnobotanical survey of plants used to manage HIV/AIDS opportunistic infections in Katima Mulilo, Caprivi region, Namibia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2010;6(1, article 25) doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chinsembu K. C. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal flora utilised by traditional healers in the management of sexually transmitted infections in Sesheke District, Western Province, Zambia. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bjp.2015.07.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chinsembu K., Hijarunguru A., Mbangu A. Ethnomedicinal plants used by traditional healers in the management of HIV/AIDS opportunistic diseases in Rundu, Kavango East Region, Namibia. South African Journal of Botany. 2015;100:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2015.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koné W. M., Atindehou K. K. Ethnobotanical inventory of medicinal plants used in traditional veterinary medicine in Northern Côte d'Ivoire (West Africa) South African Journal of Botany. 2008;74(1):76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2007.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabuti J. R. S., Dhillion S. S., Lye K. A. The status of wild food plants in Bulamogi County, Uganda. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 2004;55(6):485–498. doi: 10.1080/09637480400015745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gazzaneo L. R. S., de Lucena R. F. P., de Albuquerque U. P. Knowledge and use of medicinal plants by local specialists in an region of Atlantic Forest in the state of Pernambuco (Northeastern Brazil) Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2005;1, article 9 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canales M., Hernández T., Caballero J., et al. Informant consensus factor and antibacterial activity of the medicinal plants used by the people of San Rafael Coxcatlán, Puebla, México. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2005;97(3):429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afolayan A. J., Grierson D. S., Mbeng W. O. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the management of skin disorders among the Xhosa communities of the Amathole District, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2014;153(1):220–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedimbi M., Chinsembu K. C. Ethnomedicinal study of plants used to manage HIV/AIDS-related disease conditions in the Ohangwena region, Namibia. International Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2012;1(1):4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chinsembu K. C., Negumbo J., Likando M., Mbangu A. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat livestock diseases in Onayena and Katima Mulilo, Namibia. South African Journal of Botany. 2014;94:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2014.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mabona U., Van Vuuren S. F. Southern African medicinal plants used to treat skin diseases. South African Journal of Botany. 2013;87:175–193. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2013.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ochwang'i D. O., Kimwele C. N., Oduma J. A., Gathumbi P. K., Mbaria J. M., Kiama S. G. Medicinal plants used in treatment and management of cancer in Kakamega County, Kenya. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2014;151(3):1040–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okoth D. A., Chenia H. Y., Koorbanally N. A. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of flavonoids from Lannea alata (Engl.) Engl. (Anacardiaceae) Phytochemistry Letters. 2013;6(3):476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2013.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maregesi S. M., Pieters L., Ngassapa O. D., et al. Screening of some Tanzanian medicinal plants from Bunda district for antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral activities. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;119(1):58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agyare C., Dwobeng A. S., Agyepong N., et al. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and wound healing properties of Kigelia africana (Lam.) Beneth. and Strophanthus hispidus DC. Advances in Pharmacological Sciences. 2013;2013:10. doi: 10.1155/2013/692613.692613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Picerno P., Autore G., Marzocco S., Meloni M., Sanogo R., Aquino R. P. Anti-inflammatory activity of verminoside from Kigelia africana and evaluation of cutaneous irritation in cell cultures and reconstituted human epidermis. Journal of Natural Products. 2005;68(11):1610–1614. doi: 10.1021/np058046z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mugisha M. K., Asiimwe S., Namutebi A., Borg-Karlson A.-K., Kakudidi E. K. Ethnobotanical study of indigenous knowledge on medicinal and nutritious plants used to manage opportunistic infections associated with HIV/AIDS in western Uganda. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2014;155(1):194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Srivastav S., Singh P., Mishra G., Jha K. K., Khosa R. L. Achyranthes aspera—an important medicinal plant: a review. Journal of Natural Product and Plant Resources. 2011;1(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venkatesan N., Thiyagarajan V., Narayanan S., et al. Anti-diarrhoeal potential of asparagus racemosus wild root extracts in laboratory animals. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2005;8(1):39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akah P. A. Antidiarrheal activity of Kigelia africana in experimental animals. Journal of Herbs, Spices & Medicinal Plants. 1996;4(2):31–38. doi: 10.1300/j044v04n02_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saini S., Kaur H., Verma B., Ripudaman, Singh S. K. Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth.—an overview. Natural Product Radiance. 2009;8(2):190–197. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belayneh A., Asfaw Z., Demissew S., Bussa N. F. Medicinal plants potential and use by pastoral and agro-pastoral communities in Erer Valley of Babile Wereda, Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology & Ethnomedicine. 2012;8, article 42 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agunu A., Yusuf S., Andrew G. O., Zezi A. U., Abdurahman E. M. Evaluation of five medicinal plants used in diarrhoea treatment in Nigeria. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2005;101(1–3):27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Wet H., Nkwanyana M. N., Van Vuuren S. F. Medicinal plants used for the treatment of diarrhoea in northern Maputaland, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;130(2):284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Odda J., Kristensen S., Kabasa J., Waako P. Larvicidal activity of Combretum collinum Fresen against Aedes aegypti . Journal of Vector Borne Diseases. 2008;45(4):321–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maroyi A. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by the people in Nhema communal area, Zimbabwe. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;136(2):347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ngueyem T. A., Brusotti G., Caccialanza G., Finzi P. V. The genus Bridelia: a phytochemical and ethnopharmacological review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;124(3):339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rakotomalala G., Agard C., Tonnerre P., et al. Extract from Mimosa pigra attenuates chronic experimental pulmonary hypertension. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2013;148(1):106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vasudeva N., Vats M., Sharma S. K., Sardana S. Chemistry and biological activities of the genus Dalbergia—a review. Pharmacognosy Reviews. 2009;3(6, article 307) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akinsinde K. A., Olukoya D. K. Vibriocidal activities of some local herbs. Journal of Diarrhoeal Diseases Research. 1995;13(2):127–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mpiana P. T., Mudogo V., Tshibangu D. S. T., et al. Antisickling activity of anthocyanins from Bombax pentadrum, Ficus capensis and Ziziphus mucronata: photodegradation effect. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;120(3):413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh S., Majumdar D. K., Rehan H. M. S. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory potential of fixed oil of Ocimum sanctum (Holybasil) and its possible mechanism of action. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1996;54(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(96)83992-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sibandze G. F., van Zyl R. L., van Vuuren S. F. The anti-diarrhoeal properties of Breonadia salicina, Syzygium cordatum and Ozoroa sphaerocarpa when used in combination in Swazi traditional medicine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;132(2):506–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chinsembu K. C. Green Medicines: Pharmacy of Natural Products for HIV and Five AIDS-Related Infections. Toronto, Canada: Africa in Canada Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 51.More G., Tshikalange T. E., Lall N., Botha F., Meyer J. J. M. Antimicrobial activity of medicinal plants against oral microorganisms. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;119(3):473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ndubani P., Höjer B. Traditional healers and the treatment of sexually transmitted illnesses in rural Zambia. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1999;67(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nutan S. K., Modi M., Dezzutti C. S., et al. Extracts from Acacia catechu suppress HIV-1 replication by inhibiting the activities of the viral protease and Tat. Virology Journal. 2013;10(1, article 309) doi: 10.1186/1743-422x-10-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Narayan L. C., Rai R. V., Tewtrakul S. Emerging need to use phytopharmaceuticals in the treatment of HIV. Journal of Pharmacy Research. 2013;6(1):218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jopr.2012.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McGaw L. J., Lall N., Meyer J. J. M., Eloff J. N. The potential of South African plants against Mycobacterium infections. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;119(3):482–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bunalema L., Obakiro S., Tabuti J. R. S., Waako P. Knowledge on plants used traditionally in the treatment of tuberculosis in Uganda. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2014;151(2):999–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tabuti J. R. S., Kukunda C. B., Waako P. J. Medicinal plants used by traditional medicine practitioners in the treatment of tuberculosis and related ailments in Uganda. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;127(1):130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hurinanthan V. Anti-HIV activity of selected South African medicinal plants [Ph.D. dissertation] 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rabkin J. G., Wagner G. J., Rabkin R. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of testosterone therapy for HIV-positive men with hypogonadal symptoms. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57(2):141–147. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rabkin J. G. HIV and depression: 2008 review and update. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2008;5(4):163–171. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lamba H., Goldmeier D., Mackie N. E., Scullard G. Antiretroviral therapy is associated with sexual dysfunction and with increased serum oestradiol levels in men. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2004;15(4):234–237. doi: 10.1258/095646204773557749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murugan M., Mohan V. R. Antibacterial activity of Mucuna pruriens (L.) Dc. var. pruriensan ethnomedicinal plant. Science Research Reporter. 2011;1(2):69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shukla K. K., Mahdi A. A., Ahmad M. K., Shankhwar S. N., Rajender S., Jaiswar S. P. Mucuna pruriens improves male fertility by its action on the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis. Fertility and Sterility. 2009;92(6):1934–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suresh S., Prithiviraj E., Prakash S. Dose-and time-dependent effects of ethanolic extract of Mucuna pruriens Linn. seed on sexual behaviour of normal male rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;122(3):497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ho C. C. K., Tan H. M. Rise of herbal and traditional medicine in erectile dysfunction management. Current Urology Reports. 2011;12(6):470–478. doi: 10.1007/s11934-011-0217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moshi M. J., Mbwambo Z. H. Experience of Tanzanian traditional healers in the management of non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2002;40(7):552–560. doi: 10.1076/phbi.40.7.552.14691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldstein I., Young J. M., Fischer J., Bangerter K., Segerson T., Taylor T. Vardenafil, a new phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor, in the treatment of erectile dysfunction in men with diabetes: a multicenter double-blind placebo-controlled fixed-dose study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):777–783. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]