Abstract

Local excision (LE) for rectal cancer is currently indicated for selected T1 stage tumors. However, preoperative chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for locally advanced rectal cancer not only improves local disease control, but also leads to a decrease in the stage and size of the primary mural tumor, along with a decrease in the risk of regional lymphadenopathy. The present study reports the outcome of a patient with T3N0M0 rectal cancer who was treated with LE following preoperative CRT. The distal pole of the tumor was located 2 cm from the anal verge. Preoperative pelvic radiotherapy of 50.4 Gy was administered in 28 fractions. Chemotherapy using 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin was administered during the first and last weeks of radiotherapy. The tumor response to CRT, was found to be marked at 7 weeks after CRT completion, and a complete response was presumed clinically. Transanal full-thickness LE was performed, and pathological examination revealed the absence of residual cancer cells. After 30 months of close follow-up, the patient was alive with no evidence of disease, and treatment-associated severe toxicities were not observed. Although a longer follow-up period is required, this case report suggests that LE may also be a feasible alternative treatment for T3 rectal cancer, which exhibits a marked response to preoperative CRT, particularly in elderly and comorbid patients contraindicated for radical surgery, or patients who are reluctant to undergo sphincter-ablation surgery.

Keywords: rectal cancer, local excision, chemoradiotherapy, response

Introduction

The incidence rates for colorectal cancer have continued to increase in Korea; in 2012, colorectal cancer was the second and third most frequently diagnosed cancer in males and females, respectively (1). For rectal cancer, an improvement in surgical techniques and the introduction of multimodality treatments (radiotherapy and chemotherapy) have improved treatment outcomes (2). The standard surgical procedure for the treatment of rectal cancer is abdominoperineal resection, low anterior resection or resection with coloanal anastomosis (3). However, local excision (LE) has been regarded as an alternative method for selected cases that fulfill stringent conditions of small-sized T1 tumors with no unfavorable histological features (4). LE has advantages in rapid postoperative recovery, avoiding sphincter ablation (permanent colostomy) and morbidities associated with radical resection, such as urinary and sexual dysfunction (4).

For locally advanced rectal cancer [LARC; also referred to as stage T3–4 or N+ rectal cancer, according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual] (5), chemoradiotherapy (CRT) has been established as a standard preoperative treatment, rather than a postoperative treatment (6,7). Preoperative CRT leads to significant improvement in the local disease control of LARC (8). In addition, preoperative CRT and a 6-8-week interval prior to the surgical procedure result in a decrease in the stage and size of the primary mural tumors, along with a lower risk of regional lymphadenopathy (9). In a subset of patients exhibiting marked tumor response to CRT, preoperative CRT may transform LARC so that LE may safely replace radical surgery.

The present study presents the case of a stage T3 rectal cancer patient who was treated with LE following preoperative CRT, and discusses issues associated with this approach.

Case report

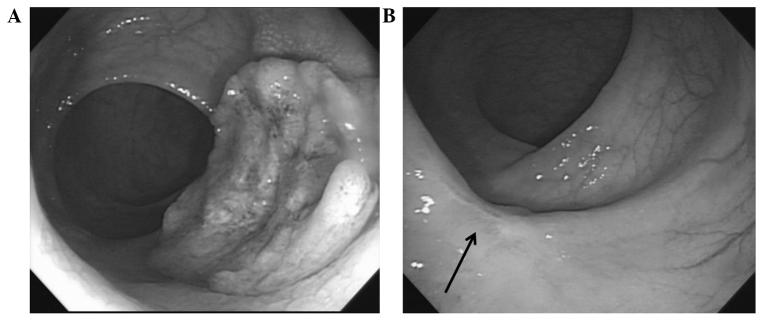

A 69-year-old male was referred to the Soonchunhyang University Hospital (Cheonan, South Korea) on 28th April 2013 for further evaluation and the treatment of rectal cancer, which was diagnosed during national medical check-ups. The patient had no specific symptoms associated with rectal cancer. The distal portion of the mass was palpated 2 cm from the anal verge on a digital rectal examination. Colonoscopy showed the presence of an ulcerofungating mass on the rectal wall (Fig. 1A). Pathological examination of a biopsy specimen revealed moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. The serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen were determined by a routine blood test and were 4.4 ng/ml (normal range, 0–5.0 ng/ml). Abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed tumor invasion into the perirectal tissues, but no enlargement of the lymph nodes was observed. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET)-CT showed a maximum standardized uptake value of 13.8 in the primary rectal tumor. The pretreatment clinical stage (cStage) was determined to be T3N0M0 (IIA) according to the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (5). The present study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board at the Soonchunhyang University Hospital.

Figure 1.

Colonoscopy images. (A) Pretreatment ulcerofungating mass on the rectal wall. (B) A scar lesion with whitening of the mucosa at 7 weeks after the completion of chemoradiotherapy (arrow).

Preoperative radiotherapy of 45 Gy in 25 fractions was delivered to the pelvis, followed by a boost of 5.4 Gy in three fractions within 5.5 weeks, according to guidelines (3). The patient underwent CT simulation in the prone position using a belly board. The target volume included the presacral space, mesorectum, gross tumor volume and the regional lymphatics, including the presacral, internal iliac, distal common iliac and perirectal lymphatics. The boost target volume included the gross tumor volume and adjacent mesorectum. A three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy plan was created using the Eclipse Treatment Planning system (Varian Medical Systems, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The three-field plan consisted of a 15-MV photon opposed lateral field with wedges of 45° and a 6-MV photon posterior-anterior field. Radiotherapy was performed using a Novalis Tx system (Varian Medical Systems, Inc.; BrainLab AG, Feldkirchen, Germany). Preoperative chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil (Ildong Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Seoul, South Korea) and leucovorin (Samjin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Seoul, South Korea) was administered concurrently with the radiotherapy. Briefly, two cycles of a bolus infusion of 5-fluorouracil (450 mg/m2/d) and leucovorin (20 mg/m2/d) were administered for 5 days during weeks 1 and 5 of radiotherapy.

At 7 weeks following preoperative CRT completion, the tumor response to CRT was assessed. The mass or stenosis was not palpated on digital rectal examination. A scar lesion with whitening of the mucosa, but no intraluminal mass or ulceration, was observed on colonoscopy (Fig. 1B). A CT scan showed diminished rectal wall thickness. Following discussion with the patient regarding the presence of a presumed complete CRT response and description of the surgical procedure methods, the patient selected to undergo LE, despite being informed that it was not the standard treatment and carried potential risks of disease recurrence. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Transanal full-thickness LE was performed with ≥1 cm margin around the scar, including the adjacent perirectal fat tissues. The defect of the rectal wall was closed by using absorbable sutures. A pathological examination was conducted according to guidelines (10), and revealed no residual cancer cells in the specimen, with no lymphovascular or perineural invasion. The patient was discharged the following day after surgery. Treatment side-effects included nausea during CRT and pain at the surgical site, both of which subsided with conservative management, including treatment with 8 mg ondansetron (GlaxoSmithKline plc., Seoul, South Korea) and Ultracet® tablets (37.5 mg tramadol HCl and 325 mg acetaminophen; Janssen Korea Ltd., Seoul, South Korea). Postoperative chemotherapy was not administered.

Follow-up evaluation consisted of physical and digital rectal examination, complete blood counts, liver function tests and measurement of carcinoembryonic antigen levels, every 3 months. Chest radiography and CT of the abdomen and pelvis were conducted every 6 months. Colonoscopy and PET-CT was performed every year. At 30 months post-treatment, the patient was alive with no evidence of disease and no severe complications.

Discussion

The current oncology practice guidelines describe the use of LE on rectal cancer appropriate only for highly selected patients with a good prognosis. The eligibility criteria for LE in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines include the following: T1 tumor stage, tumor size of <3 cm, <30% bowel circumference, clear margin (>3 mm), mobile non-fixed, no lymphovascular or perineural invasion, well-to-moderate differentiation and no lymphadenopathy on pretreatment imaging (3). Stage T2–3 rectal cancer is excluded from LE indications. However, T2–3 rectal tumors are a heterogeneous group when assessed by CRT response. Patients with LARC were demonstrated to have various outcomes according to the degree of response to preoperative CRT (11,12). In a previous study, patients with an initial cStage II–III and post-treatment (y) pathological (p)Stage 0-I rectal cancer (staged according to the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual) (5), showed similar favorable outcomes as patients with pStage I cancer (7). Therefore, the current LE criteria for T1 rectal cancer may be expanded to include a subgroup of T2–3 rectal cancer that exhibits excellent tumor response to preoperative CRT.

Few prospective clinical trials have been conducted to address the feasibility of LE following preoperative CRT in T2–3 rectal cancer (13–15). In a previous trial in Italy, 63 patients with T2 (n=21) or T3 (n=42) rectal cancer were enrolled, and clinical lymphadenopathy was present in 39 patients (62%) (13). The criteria of observation following LE (ypStage T0–1 with no cancer cells on resected specimen margins) were satisfied in 43 patients (68%); among them, only 1 patient developed recurrence, which presented as distant metastases. In another trial in Poland, 86 patients with T1-3N0 rectal cancer received a short-course of radiotherapy or a long-course of CRT, both with a 6-week interval until LE (14). A total of 63 (71%) patients responded well to treatment, defined as ypT0–1 without unfavorable prognostic factors (positive margin, tumor fragmentation, grade 3, lymphovascular or perineural invasion) (14). In these patients, the Kaplan-Meier incidence of local recurrence at 2 years was 10%, with no significant difference between the two preoperative treatments (14). No solitary distant metastasis was observed.

To the best of our knowledge, only one randomized controlled trial has been conducted to date. In this trial by Lezoche et al (15), patients with rectal cancer of a small size (≤3 cm), T2N0 stage, well-to-moderately differentiated and distal location were randomized following preoperative CRT, in order to receive transanal endoscopic microsurgery or laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. Long-term oncological outcomes, including local recurrence, distant metastasis and cancer-associated survival, were not significantly different between the two groups. Disease recurrence, local or distant, developed only in patients with low or no response to preoperative CRT in both treatment groups.

Although full-thickness LE occasionally retrieves 1–2 lymph nodes adjacent to the primary tumor, it can not address mesorectal lymph nodes as thoroughly as total mesorectal excision (16). Overall, without preoperative treatments, T1 rectal cancer has a 10–20% rate of lymph node metastasis (4,16). When excluding T1 tumors possessing high-risk clinical and histological features, this rate is <10%; this T1 subgroup constitutes the current inclusion criteria for LE (16). In LARC, post-CRT positive ypN rates in ypT0–1 have been reported to be <10% (17). Metastatic cancer cells on lymph nodes regress along the primary tumor regression by CRT. The clinical stage of the present case was determined to be T3N0; even when subclinical mesorectal lymph node disease was presumed to be present, CRT may have been sufficient for microscopic disease eradication. Significant tumor regression following CRT also represents favorable biological tumor behavior (12).

An obstacle in implementing this approach in patients with rectal cancer is the limited ability for preoperative clinical or radiological assessment of the post-CRT tumor status (18). Radiology investigations using PET and diffusion-weighted MRI are undergoing to improve the accuracy in evaluating the response of rectal cancer to CRT (19,20). However, the post-LE ypT status (ypT0-1) remains the most reliable parameter for determining whether to proceed with LE. Radical resection following initial LE in patients who exhibit a lower than predicted response was reported to not compromise long-term outcomes (21,22). Among the pretreatment patient or tumor characteristics, low serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (≤5 ng/ml) have been demonstrated to be independently associated with a good pathological response of LARC to CRT (23). The patient discussed in the present study had carcinoembryonic antigen levels of 4.4 ng/ml, and a post-CRT pathological complete response.

LE requires strict adherence to an intense surveillance schedule to detect any recurrence early in order to provide salvage treatment. The present patient has been disease-free for 30 months post-treatment; however, further close follow-up is required as rectal cancer has a tendency for late recurrence following preoperative CRT (24).

In conclusion, the present case report supports that LE may be a feasible alternative for T3 rectal cancer treatment following significant response to CRT. The physician may need to discuss this treatment option with a patient suspected of a significant CRT response. Until further prospective and randomized clinical trials are conducted, this approach may be particularly valuable in elderly and comorbid patients for whom radical surgery, currently the sole standard treatment, includes high morbidity and mortality risks, or patients who are reluctant to undergo sphincter-ablation surgery.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

References

- 1.Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Cho H, Lee DH, Lee KH. Cancer statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2012. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47:127–141. doi: 10.4143/crt.2015.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosinski L, Habr-Gama A, Ludwig K, Perez R. Shifting concepts in rectal cancer management: A review of contemporary primary rectal cancer treatment strategies. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:173–202. doi: 10.3322/caac.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN): Rectal cancer. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. [Nov 23;2014 ];NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Version 1. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maeda K, Koide Y, Katsuno H. When is local excision appropriate for ‘early’ rectal cancer? Surg Today. 2014;44:2000–2014. doi: 10.1007/s00595-013-0766-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JW, Lee JH, Kim JG, Oh ST, Chung HJ, Lee MA, Chun HG, Jeong SM, Yoon SC, Jang HS. Comparison between preoperative and postoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: An institutional analysis. Radiat Oncol J. 2013;31:155–161. doi: 10.3857/roj.2013.31.3.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeo SG, Kim DY, Park JW, Choi HS, Oh JH, Kim SY, Chang HJ, Kim TH, Sohn DK. Stage-to-stage comparison of preoperative and postoperative chemoradiotherapy for T3 mid or distal rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:856–862. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeo SG, Kim DY. An update on preoperative radiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2012;28:179–187. doi: 10.3393/jksc.2012.28.4.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeo SG, Kim DY, Kim TH, Chang HJ, Oh JH, Park W, Choi DH, Nam H, Kim JS, Cho MJ. Pathologic complete response of primary tumor following preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: Long-term outcomes and prognostic significance of pathologic nodal status (KROG 09–01) Ann Surg. 2010;252:998–1004. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f3f1b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Montgomery EA. Gastrointestinal and Liver Pathology. In: Goldblum JR, editor. Foundations in Diagnostic Pathology. 2nd. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeo SG, Kim DY, Park JW, Oh JH, Kim SY, Chang HJ, Kim TH, Kim BC, Sohn DK, Kim MJ. Tumor volume reduction rate after preoperative chemoradiotherapy as a prognostic factor in locally advanced rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e193–e199. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, Das P, Rödel C, Kuo LJ, Calvo FA, García-Aguilar J, Glynne-Jones R, Haustermans K, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: A pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:835–844. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pucciarelli S, De Paoli A, Guerrieri M, La Torre G, Maretto I, De Marchi F, Mantello G, Gambacorta MA, Canzonieri V, Nitti D, et al. Local excision after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: Results of a multicenter phase II clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1349–1356. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182a2303e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bujko K, Richter P, Smith FM, Polkowski W, Szczepkowski M, Rutkowski A, Dziki A, Pietrzak L, Kołodziejczyk M, Kuśnierz J. Preoperative radiotherapy and local excision of rectal cancer with immediate radical re-operation for poor responders: A prospective multicentre study. Radiother Oncol. 2013;106:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lezoche E, Baldarelli M, Lezoche G, Paganini AM, Gesuita R, Guerrieri M. Randomized clinical trial of endoluminal locoregional resection versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for T2 rectal cancer after neoadjuvant therapy. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1211–1218. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heafner TA, Glasgow SC. A critical review of the role of local excision in the treatment of early (T1 and T2) rectal tumors. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;5:345–352. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2014.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Read TE, Andujar JE, Caushaj PF, Johnston DR, Dietz DW, Myerson RJ, Fleshman JW, Birnbaum EH, Mutch MG, Kodner IJ. Neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: Histologic response of the primary tumor predicts nodal status. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:825–831. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hingorani M, Hartley JE, Greenman J, Macfie J. Avoiding radical surgery after pre-operative chemoradiotherapy: A possible therapeutic option in rectal cancer? Acta Oncol. 2012;51:275–284. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.636756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JW, Kim HC, Park JW, Park SC, Sohn DK, Choi HS, Kim DY, Chang HJ, Baek JY, Kim SY, et al. Predictive value of (18)FDG PET-CT for tumour response in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated by preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:1217–1224. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1657-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genovesi D, Filippone A, Ausili Cèfaro G, Trignani M, Vinciguerra A, Augurio A, Di Tommaso M, Borzillo V, Sabatino F, Innocenti P, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance for prediction of response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: Preliminary results of a monoinstitutional prospective study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.07.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gagliardi G, Newton TR, Bailey HR. Local excision of rectal cancer followed by radical surgery because of poor prognostic features does not compromise the long term oncologic outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:e659–e664. doi: 10.1111/codi.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levic K, Bulut O, Hesselfeldt P, Bülow S. The outcome of rectal cancer after early salvage TME following TEM compared with primary TME: A case-matched study. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:397–403. doi: 10.1007/s10151-012-0950-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeo SG, Kim DY, Chang HJ, Park JW, Oh JH, Kim BC, Baek JY, Kim SY, Kim TH. Reappraisal of pretreatment carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with rectal cancer receiving preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Tumori. 2013;99:93–99. doi: 10.1177/030089161309900116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeo SG, Kim MJ, Kim DY, Chang HJ, Baek JY, Kim SY, Kim TH, Park JW, Oh JH, Kim MJ. Patterns of failure in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer receiving pre-operative or post-operative chemoradiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:114. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]