Significance

Because of the toxicity gain of expanded polyglutamine (polyQ) repeats, many studies have used RNAi and other approaches to inactivate the mutant HTT gene in Huntington’s disease. However, Htt is essential for early embryonic development, and normal function of Htt in adult animals remains unknown. Using conditional Htt knockout mice, we found that loss of Htt causes the lethal phenotype only in postnatal mice but not in adult mice, and this early death is due to acute pancreatitis. Htt interacts with serine protease inhibitor Kazal-type 3 (Spink3) to inhibit trypsin activity in pancreatic cells and thus prevents acinar cell degeneration and pancreatitis. This age- and cell type-dependent function indicates the safety in knocking down neuronal HTT in adult brains for treating Huntington’s disease.

Keywords: Huntingtin, aging, degeneration, acinus, pancreas

Abstract

The Huntington’s disease (HD) protein, huntingtin (HTT), is essential for early development. Because suppressing the expression of mutant HTT is an important approach to treat the disease, we must first understand the normal function of Htt in adults versus younger animals. Using inducible Htt knockout mice, we found that Htt depletion does not lead to adult neurodegeneration or animal death at >4 mo of age, which was also verified by selectively depleting Htt in neurons. On the other hand, young Htt KO mice die at 2 mo of age of acute pancreatitis due to the degeneration of pancreatic acinar cells. Importantly, Htt interacts with the trypsin inhibitor, serine protease inhibitor Kazal-type 3 (Spink3), to inhibit activation of digestive enzymes in acinar cells in young mice, and transgenic HTT can rescue the early death of Htt KO mice. These findings point out age- and cell type-dependent vital functions of Htt and the safety of knocking down neuronal Htt expression in adult brains as a treatment.

Huntington’s disease (HD) is caused by polyglutamine (polyQ) expansion in the N-terminal region of huntingtin (HTT). Despite its ubiquitous expression in the brain and body, mutant HTT causes selective neuronal degeneration as well as white matter atrophy in the brain (1–3). The neuronal degeneration is characterized by the preferential loss of neuronal cells in the striatum in the early disease stage and extensive neurodegeneration in a variety of brain regions in later disease stages. This progressive neurodegeneration is consistent with the late-onset neurological symptoms of HD, and age-dependent toxicity of mutant HTT is thus a characteristic of HD.

HTT consists of 3,144 amino acids and is thought to be a scaffold protein that associates with a number of other proteins and participates in a wide range of cellular functions, including intracellular trafficking of a variety of proteins (1, 4). HTT is important during animal early development, as germ-line deletion of Htt leads to early death of mice at embryonic day 8.5 (5–7). A variety of HD animal models that express mutant HTT provide strong evidence for an age-dependent toxic gain of function of mutant HTT (8–12), and considerable efforts have been devoted to developing siRNA and antisense oligonucleotides to suppress the expression of mutant HTT in adult brains (13–15). Unfortunately, however, these approaches have also raised concerns that markedly suppressing HTT expression will lead to side effects by impairing HTT’s normal function. To date, whether HTT has differential roles in early development and adulthood remains unknown. Clarifying these distinctions is vital if we are to develop a better strategy for treating HD.

Using conditional Htt knockout mice to mate with transgenic CAG-CreER mice that express Cre-ER ubiquitously in the body and brain and transgenic mice expressing Cre-ER in neuronal cells, we generated inducible Htt knockout mice and found that loss of Htt in adult mouse brain does not cause obvious neuropathology and phenotypes. However, depletion of Htt in the whole body of young mice causes animal death as a result of acute pancreatitis from the degeneration of pancreatic acinar cells. We also found that Htt interacts with the trypsin inhibitor, serine protease inhibitor Kazal-type 3 (Spink3), to reduce trypsin activity. Thus, Htt has different roles that depend on age and cell types. Our studies show that removing Htt in adult neuronal cells does not lead to degeneration or detectable phenotypes in mice, suggesting that the complete removal of neuronal HTT in the adult brain is possible to achieve an efficient treatment for HD.

Results

Loss of Htt Mediates Age-Dependent Death in Mice.

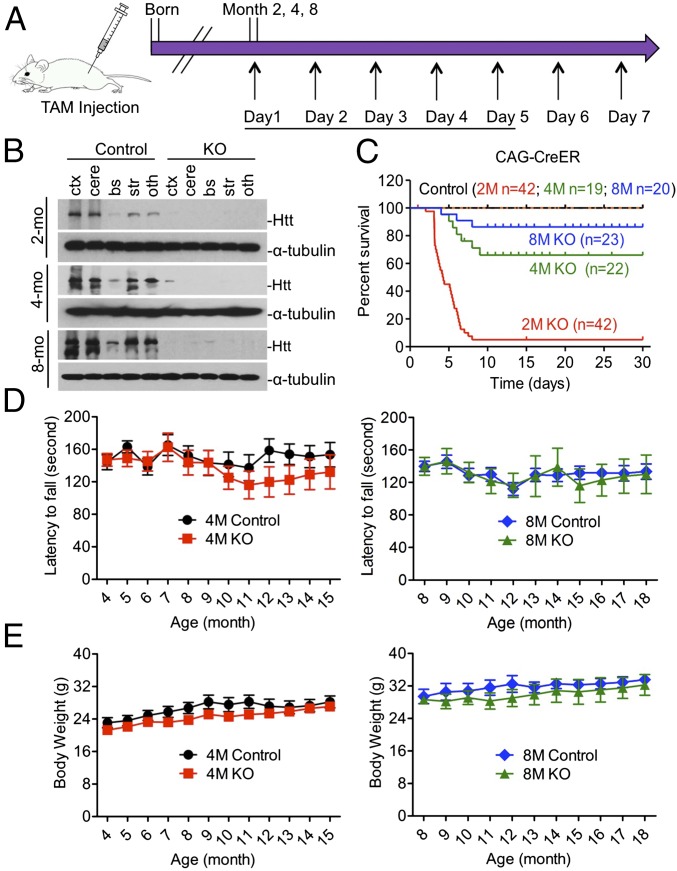

To investigate the function of Htt in adult mice, we crossed conditional Htt KO mice (16) to transgenic CAG-CreER mice that ubiquitously express a tamoxifen-inducible CreER, resulting in inducible Htt KO (ubiquitous KO) mice that would deplete Htt expression upon tamoxifen injection (Fig. 1A). We injected tamoxifen into ubiquitous KO mice at 2, 4, and 8 mo of age and Western blot analysis confirmed that tamoxifen injection caused Htt depletion in various brain regions in ubiquitous KO mice at different ages (Fig. 1B). Quantification of the life span clearly indicated an age-dependent death of ubiquitous KO mice: more than 95% of 2-mo-old mice died within 10 d after Htt depletion, whereas 70% of 4-mo-old and 95% of 8-mo-old mice could survive after Htt depletion (Fig. 1C). For older ubiquitous KO mice, there were no significant differences in the rotarod performance and body weight gain compared with their controls (Fig. 1 D and E). We also verified that the depletion of Htt in ubiquitous KO mice caused no significant changes in LC3I/II, P62, Caspase-3, NFκB, and FAT10 in the brain and peripheral tissues (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Loss of Htt-mediated age-dependent death in mice. Control is heterozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice injected with tamoxifen, and KO is homozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice injected with tamoxifen. (A) Diagram depicting inactivation of the Htt gene in adult mouse expressing CreER. The mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with tamoxifen (TAM) 20 mg/mL for 5 continuous days. Mice were examined for 7–11 mo after tamoxifen injection. (B) Western blots showing relative Htt protein levels in the brain of ubiquitous KO and control mice at 2, 4, and 8 mo of age. Ctx, cortex; cere, cerebellum; bs, brainstem; str, striatum; oth, other brain regions. (C) Survival rate of ubiquitous KO mouse and control mice when they were injected with tamoxifen at 2, 4, and 8 mo of age. (D and E) The rotarod performance (D) and body weight (E) of ubiquitous KO mice whose Htt was depleted at 4 or 8 mo of age, the mice were then studied for 10–11 mo after tamoxifen injection. Control is age-matched heterozygous KO mice.

Fig. S1.

The expression of autophagy markers in the brain and peripheral tissues of adult ubiquitous Htt KO mice. (A–C) Representative immunoblots (A) and quantification of (B) Htt, P62, and (C) LC3I/II ratio in ubiquitous KO and control mice (n = 3 independent experiments). (D and E) Western blotting of the spleen (D) and liver (E) in control and ubiquitous KO mice. The blots were probed by antibodies to cleaved caspase3, P62, LC3I/II, NF-κB, and FAT10 after tamoxifen injection for 3 d. Alpha-tubulin was probed as a loading control. Animal ID numbers are indicated. Ctl: heterozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice injected with tamoxifen; KO: homozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice injected with tamoxifen.

Depletion of Neuronal Htt in Adult Mice Does Not Cause Death.

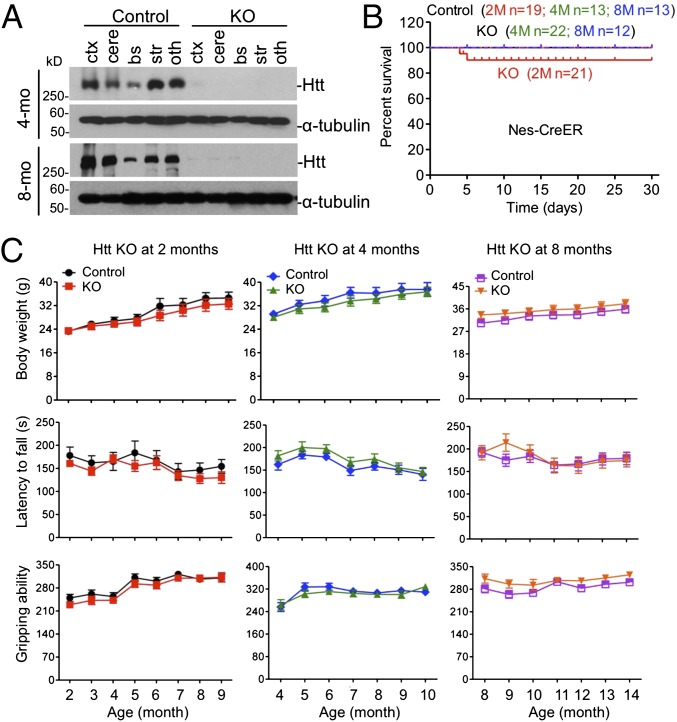

The above studies suggested that depletion of Htt in the brain might not be responsible for the death of young mice. To confirm this, we crossed floxed Htt mice with transgenic mice expressing Nestin-CreER, such that the resulting crossed mice (neuronal KO) had selectively depleted Htt expression in neuronal cells after tamoxifen injection, as Cre expression is driven by the neuronal Nestin promoter. Western blot analysis confirmed that tamoxifen injection caused Htt depletion in various brain regions in neuronal KO mice at different ages (Fig. 2A). As expected, very few (<18%) 2-mo-old neuronal KO mice died, and all neuronal KO mice >4 mo lived normally after Htt was depleted by tamoxifen injection (Fig. 2B). These living mice showed the same body weight, rotarod performance, and gripping ability as their controls (Fig. 2C). Because depletion of Htt is known to affect the neurogenesis or survival of developing neurons (16, 17), we examined 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO mice, but found no difference in the brain size and volume between controls and Htt KO mice (Fig. 3 A and B). For neuronal KO mice, depletion of Htt by tamoxifen for 90 d did not show any difference in the brain volume compared with control mice (Fig. 3B). Histological examination showed no morphologic defects in neuronal KO mice (Fig. S2A), which is supported by Western blotting results that detected no significant changes in NeuN, β-tubulin III, GFAP, P62, LC3I/II, and caspase-3, except mouse Htt protein (Fig. 3 C and D). Immunofluorescent staining also did not show any changes in LC3I/II, β-tubulin III, and cleaved caspase-3 staining in ubiquitous and neuronal KO mouse brains (Fig. 3E and Fig. S2B). In addition, we crossed floxed Htt mice to transgenic mice that express CreER in the forebrain under the control of the neuronal promoter CaMKII. The crossed mice, upon tamoxifen injection, showed normal growth and survival without any detectable brain atrophy or degeneration (Fig. S3). Taken together, our results demonstrate that ubiquitous KO mice show an age-dependent death that is unlikely due to the depletion of Htt in neuronal cells or neuronal degeneration.

Fig. 2.

Neuronal Htt knockout mice. (A) Western blots showing depletion of Htt in the brain of neuronal KO mice at 4 and 8 mo of age. See Fig. 1 for abbreviations key. (B) Survival rate of neuronal KO mice compared with the heterozygous control mice. Data were collected from the first day after tamoxifen injection. (C) Diagram showing the body weight, rotarod performance, and gripping ability at different months. Mice at different ages (2, 4, and 8 mo) were studied for 7–8 mo after tamoxifen injection (2-mo-old, n = 10; KO, male = 6 and female = 4; control, male = 4 and female = 6; 4-mo-old, n = 10; KO, male = 5 and female = 5; control, male = 5 and female = 5; 8-mo-old, KO, n = 9, male = 4, female = 5; control, n = 11, male = 6, female = 5; two-way ANOVA test, body weight, 2M control vs. 2M KO: P = 0.9945, 4M control vs. 4M KO: P = 0.9862, 8M control vs. 8M KO P = 0.9922; rotatod performance, 2M control vs. 2M KO: P = 0.9565, 4M control vs. 4M KO: P = 0.9921, 8M control vs. 8M KO P = 0.7701; gripping ability, 2M control vs. 2M KO: P = 1.0000, 4M control vs. 4M KO: P = 0.9962, 8M control vs. 8M KO P = 0.9718).

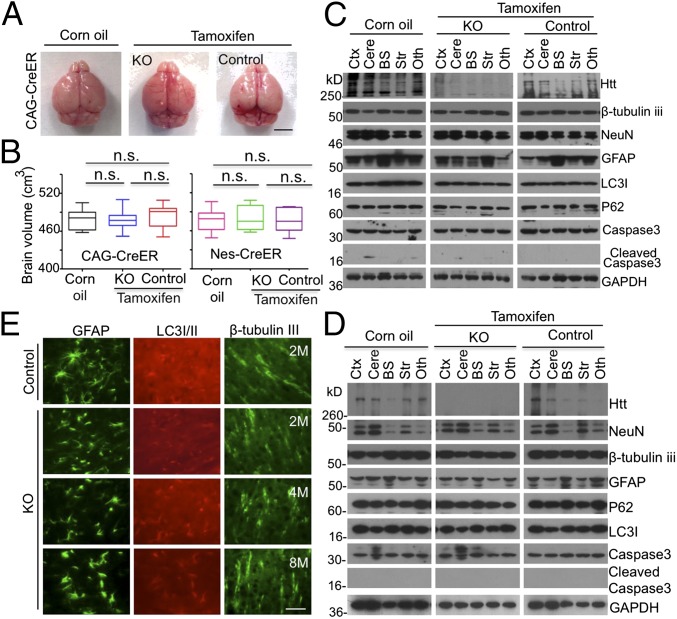

Fig. 3.

Normal brains in adult mice that have depleted Htt. (A) The brain photos of 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO mice that had been injected with tamoxifen for 5 d. (B) Brain volumes of 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO mice in A and neuronal KO mice that were injected with tamoxifen at 2 mo of age and used to isolate their brains at the 90th day after tamoxifen injection (one-way ANOVA test, ubiquitous KO: n = 7, P = 0.8759, F = 0.1335; n = 7; neuronal KO: P = 0.9665, F = 0.03416; n.s. represents no significant differences). (Scale bar, 3 mm.) (C and D) Western blotting analysis of the brain tissues from 2-mo-old ubiquitous (C) and neuronal (D) KO mice. Htt, neuronal (NeuN, β-tubulin III), astrocytic (GFAP), autophagic (P62, LC3I/II), apoptotic (cleaved caspase3), and GAPDH were detected by their antibodies. Control is heterozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER (C) or heterozygous floxed Htt/Nestin-CreER (D) mice injected with tamoxifen and homozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER (C) or homozygous floxed Htt/Nestin-CreER (D) mice injected with corn oil. KO is homozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER (C) or homozygous floxed Htt/Nestin-CreER (D) mice injected with tamoxifen. See Fig. 1 for abbreviations key. (E) Immunostaining of GFAP, LC3I/II, and β-tubulin III in the cortex of 2-, 4- and 8-mo-old ubiquitous KO and control mice. (Scale bar, 50 μm.)

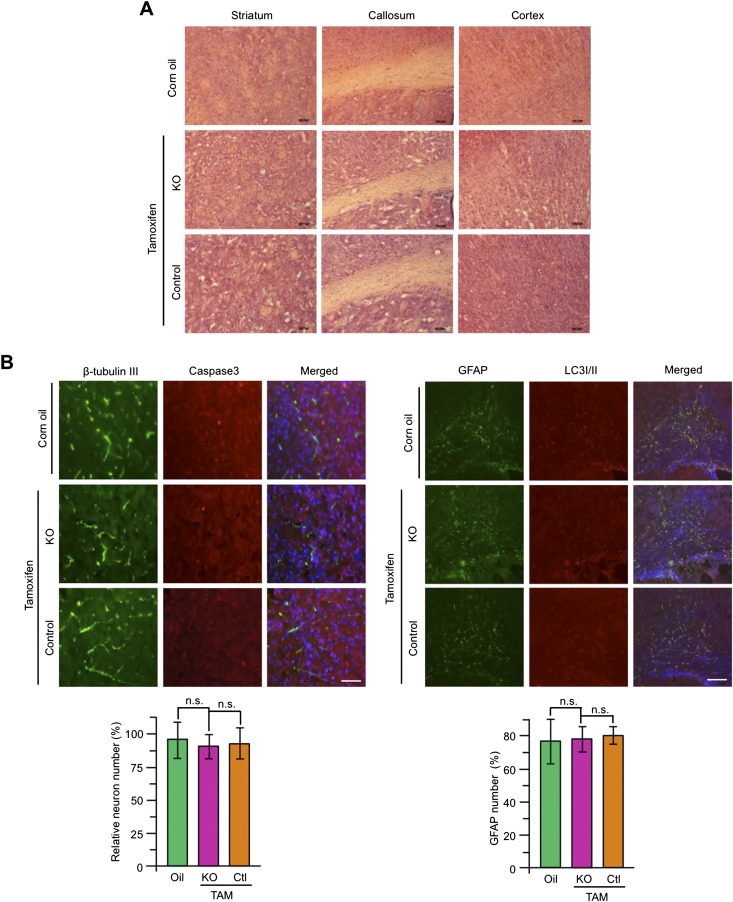

Fig. S2.

Neuronal Htt KO mice brain. (A) Photographs of H&E-stained coronal sections of the control and neuronal Htt KO mouse brain at the 90th day after tamoxifen injection. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (B) Immunostaining of β-tubulin, cleaved caspase3, GFAP, and LC3I/II in the brains of neuronal Htt KO and control mice at the 90th day after tamoxifen induction. The relative numbers of NeuN- or GFAP-positive cells are shown below the images. TAM: tamoxifen. [Scale bar, 50 μm (Left), 200 μm (Right).] Ctl: heterozygous floxed Htt/Nestin-Cre mice injected with tamoxifen; oil: homozygous floxed Htt/Nestin-Cre mice injected with corn oil; KO: homozygous floxed Htt/Nestin-Cre mice injected with tamoxifen.

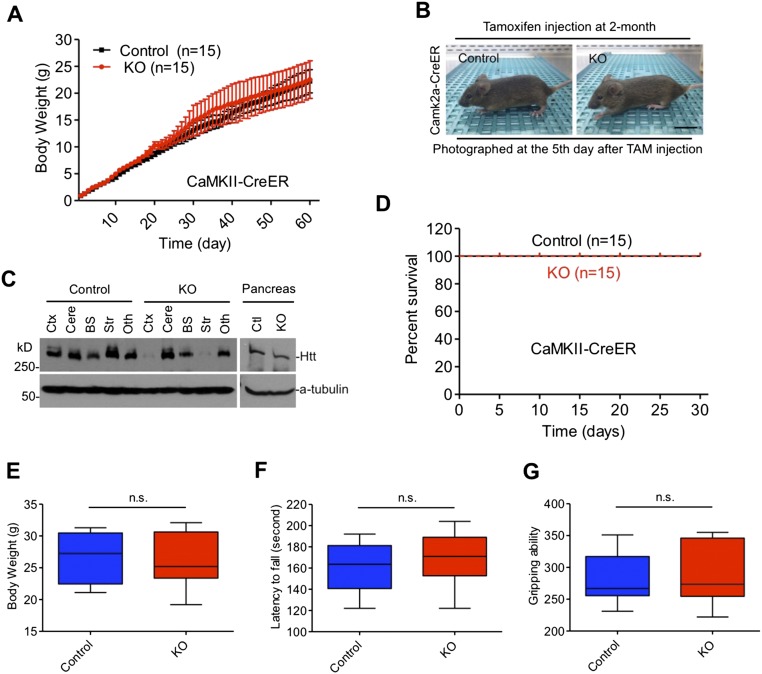

Fig. S3.

Forebrain Htt knockout does not affect mice survival. Inactivation of Htt in the forebrain is mediated by tamoxifen injection into floxed Htt mice expressing CaMKII promoter-driven CreER. (A) Body weights of floxed Htt mice expressing CaMKII-CreER and control mice from birth to adult without tamoxifen injection. *P < 0.05, *P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (B) The normal appearance of forebrain Htt KO mouse at 2 mo of age after inactivation of Htt, heterozygous KO mouse was used as a control. (Scale bar, 10 mm.) (C) Western blots showing that tamoxifen injection selectively depletes Htt expression in the brain tissues of forebrain Htt KO mice. (D) Survival curves of forebrain KO mice compared with control mice. (KO: n = 15, male = 8, female = 7; control: n = 15, male = 7, female = 8). (E–G) Body weight (E), rotarod performance (F), and gripping ability (G) in forebrain KO mice and control mice. Htt inactivation was mediated by tamoxifen injection at 2 mo of age, and the injected mice were measured at 6 mo of age (KO: n = 10, male = 6, female = 4; control: n = 10, male = 4, female = 6). Control (Ctl): heterozygous floxed Htt/CaMKII-CreER mice injected with tamoxifen; KO: homozygous floxed Htt/CaMKII-CreER mice injected with tamoxifen.

Htt Depletion Causes Acute Pancreatitis That Results from Acinar Cell Degeneration in Young Mice.

We next focused on the peripheral tissue morphology of dead ubiquitous KO mice and found abnormal and inflamed abdominal cavities (Fig. 4A). There was significant inflammation in the abdominal organs, including intestine, vessels, and pancreas, as evidenced by hemorrhagic, black-brown necrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma and peripancreatic fat (Fig. 4A and Fig. S4A). The pancreas was swollen and did not show the typical tan, lobulated architecture. All these features indicate acute pancreatitis. We then examined 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO mice after injecting tamoxifen to induce Htt depletion for different days and found the typical acute pancreatitis changes: the acinar cells were initially enlarged at day 3, and then the mice started to have ascites, ileus, and splanchnic hyperemia before their death at day 7 (Fig. 4B). Western blot results confirmed that Htt in pancreas is depleted in ubiquitous KO mice (Fig. 4C). However, histological examination revealed that living ubiquitous KO mice at 4 and 8 mo of age, which had been injected with tamoxifen for 5 d, show no abnormal pancreatic histology (Fig. S4B). Examination of ubiquitous KO mice that were injected with tamoxifen at 4 or 8 mo of age and then used to isolate their tissues 2 mo later did not reveal any abnormal histology in their pancreas.

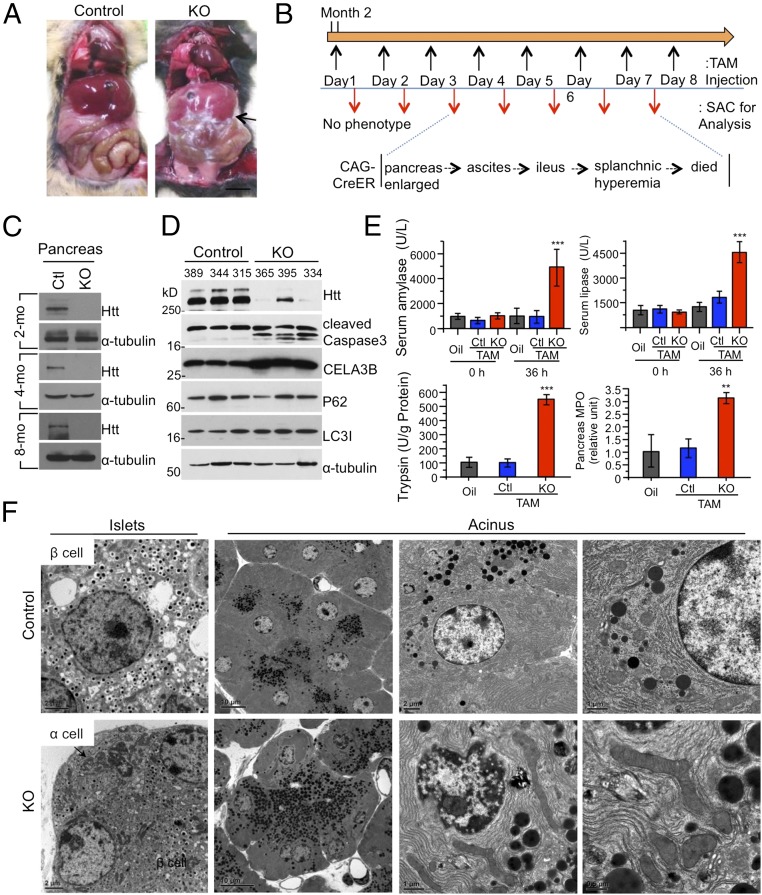

Fig. 4.

Acute pancreatitis in 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO mice. (A) Photographs of abdominal cavity of 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO (CAG-CreER) and the heterozygous control mice after 3-d injections of tamoxifen. (Scale bar, 8 mm.) (B) Scheme outlining tamoxifen (TAM) injection followed by sacrificing (SAC) for analysis. (C) Western blots confirming Htt depletion in the pancreas tissues of ubiquitous KO mice. (D) Immunoblotting of pancreas lysates was performed with antibodies against cleaved caspase-3, P62, LC3I/II, CELA3B, and α-tubulin. The samples were obtained from ubiquitous KO and control mice (2 mo old) after i.p. tamoxifen injection for 3 d. (E) Serum amylase, serum lipase, pancreas trypsin activity, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels were measured 40 h after tamoxifen injection in ubiquitous KO and control mice. Data represent the means of eight control and ubiquitous KO mice at each interval ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, four mice per group, n = 3 independent experiment, one-way ANOVA test). (F) Electron microscopy showing acinar cell degeneration in the pancreas of 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO mouse. (Scale bars, 2 μm.) Control is heterozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice injected with tamoxifen. Quantitative analysis of zymogen granules and degenerated cells is presented in Fig. S4D.

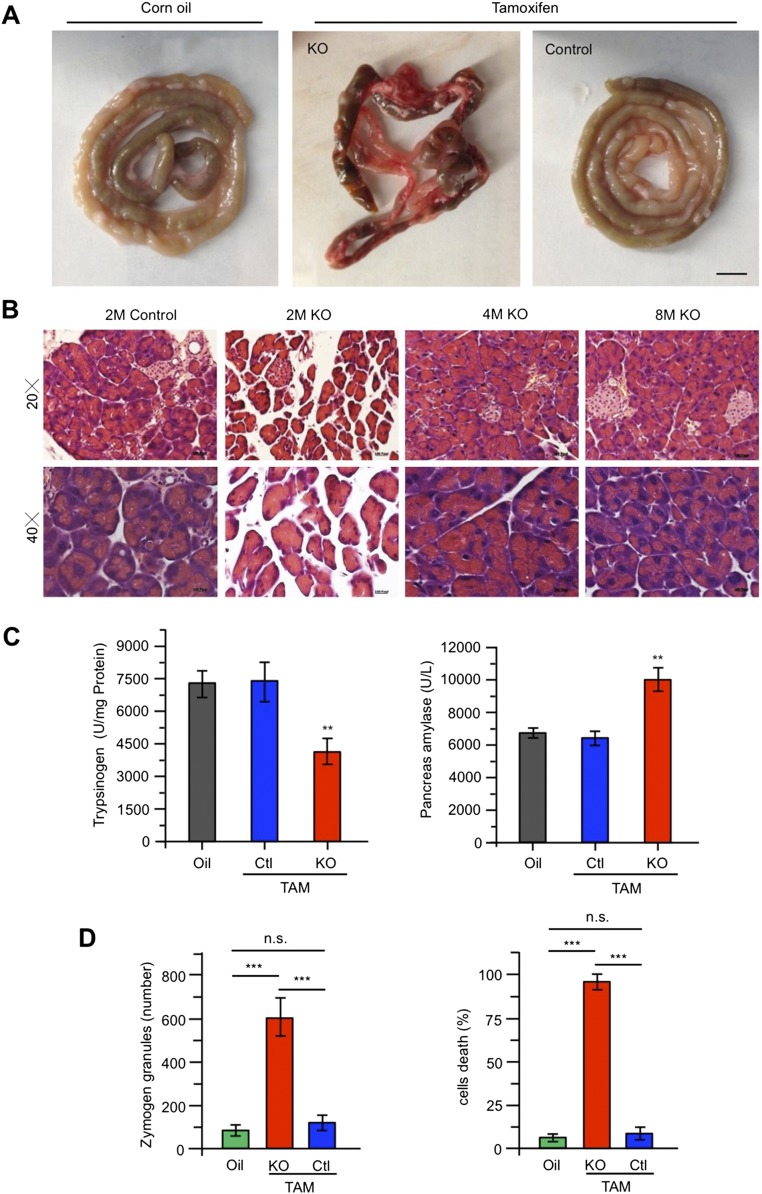

Fig. S4.

Histology of pancreas in ubiquitous Htt KO mice at 2 mo of age. (A) Intestine morphology in 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO or control mice injected with corn oil or tamoxifen. (Scale bar, 5 mm.) (B) H&E staining of the acinar cells and islets in the pancreas in the control and ubiquitous KO mice at 2, 4, and 8 mo of age after tamoxifen injection for 5 d. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (C) Pancreas trypsinogen and pancreas amylase activity were measured after TAM injection 40 h in ubiquitous KO and control mice. Data represent the means of eight animals of control and ubiquitous KO mice at each interval ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, each group tested four mice, n = 3 independent experiment, one-way ANOVA test). Control is heterozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice injected with tamoxifen or homozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice injected with oil, whereas KO is homozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice injected with tamoxifen. (D) Comparison of zymogen granules and the number of degenerated acinar cells in control and ubiquitous KO mice. [The data are mean ± SEM, paired two-tailed t test. For zymogen granules, counting a total of oil (585), KO (2,232), and control (592) zymogens: oil vs. Ctl: P = 0.9537, oil vs. KO: P = 0.0028, Ctl vs. KO: P = 0.0034. For degeneration cells, counting a total of 50–80 cells in five independent samples per group for degeneration cells, oil vs. Ctl: P = 0.5772, oil vs. KO: P = 5.546 x E−7, Ctl vs. KO: P = 7.554 x E−7]. Corn oil: homozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice injected with oil; control: heterozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice injected with tamoxifen; KO: homozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice injected with tamoxifen.

Elastase 3B or protease E (CELA3B), which is secreted from the pancreas as a zymogen, is also increased (Fig. 4D). Although autophagy activation can also be the cause of acute pancreatitis (18), we saw no significant alteration in P62 and LC3I/II, whereas caspase-3 activation was evident (Fig. 4D). Acute pancreatitis is often caused by intrapancreatic activation of pancreatic enzymes. Indeed, serum amylase, lipase, pancreas amylase, trypsin, and other pancreatic enzymes show high activities in 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO mice (Fig. 4E and Fig. S4C).

Next, we performed electron microscopic examination of pancreatic tissues of 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO mice. Compared with the pancreatic tissue from control mice (heterozygous floxed Htt mice injected with tamoxifen), we found increased zymogen granules in acinar cells, nuclear chromatin clumping, and margination, indicating apoptosis, mitochondria enlargement, and edema, as well as lysosomes containing degenerated cytoplasmic elements or organelles (Fig. 4F). Quantification of zymogene granules and apoptosis or necrosis in pancreatic acinar cells also confirmed that Htt depletion increased the accumulation of zymogene granules and acinar cell death (Fig. S4D).

Htt Interacts with Spink3 to Inhibit Trypsin Activity.

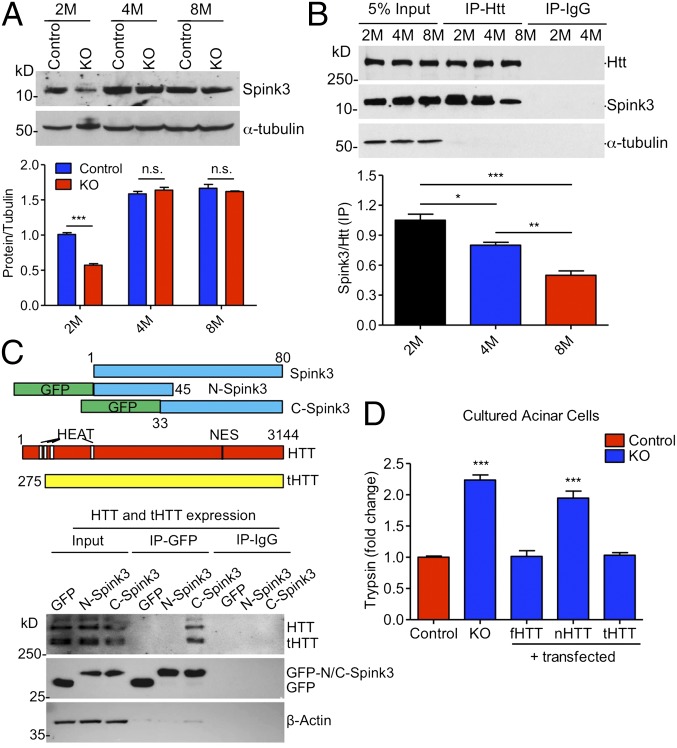

The phenotypes and morphological studies of 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO mice clearly indicate acute pancreatitis caused by Htt depletion. The acute pancreatic inflammation can be induced by activation of digested enzymes in pancreatic zymogens in acinar cells (19–21). This activation normally involves a hydrolysis reaction of inactivated forms of enzymes by trypsin. Because we saw the degeneration of acinar cells, we focused on the molecules known to inhibit trypsin activity in acinar cells. Western blot results show that Spink3, a mouse homolog of human SPINK1 that inhibits trypsin in acinar cells (22), is selectively decreased in 2-mo-old mouse pancreatic tissues compared with 4- and 8-mo-old mouse pancreatic tissues (Fig. 5A). Because mutations in the human Spink3 homolog SPINK1 cause pancreatitis (23–26) and the selective decrease of Spink3 in young mouse pancreas is associated with acute pancreatitis in 2-mo-old ubiquitous KO mice, we further investigated whether Htt associates with Spink3 to inhibit trypsin. Using immunoprecipitation of pancreatic tissues from wild-type mice at 2, 4, and 8 mo of age, we found an age-dependent association of Htt with Spink3, which declines from 2 to 8 mo (Fig. 5B). This result suggests that the association of Htt with Spink3 in pancreatic tissues in young mice may be more important for Spink3’s function.

Fig. 5.

Interaction of Htt with Spink3 inhibits trypsin activity. (A) Western blotting (Upper) and quantification (Lower) of Spink3 in 2-, 4-, and 8-mo-old ubiquitous KO and control mice. (n = 3 independent experiments, two-way ANOVA test; n.s. represents no significant difference, ***P < 0.001). (B) Immunoprecipitation of Htt with Spink3 from 2-, 4-, and 8-mo-old WT mouse pancreas. More Spink3 in 2-mo-old than 4- or 8-mo-old mouse pancreas was precipitated with Htt. Anti–α-tubulin and IgG IP were used as control. n = 3 independent experiments. One-way ANOVA test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (C) Schematic structures (Upper) of Spink3 and Htt proteins, and Western blots (Lower) showing coimmunoprecipitation of transfected GFP, GFP-N-Spink3, or GFP-C-Spink3 and truncated HTT (tHTT) in HEK293 cells. IgG immunoprecipitation served as controls. (D) Relative activities of trypsin in the control and ubiquitous KO mouse pancreatic acinar cells that were transfected with full-length Htt (fHTT), N-terminal Htt (nHTT), and truncated Htt lacking N-terminal 169 amino acids (tHTT). n = 3 independent experiments, two-way ANOVA test, P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

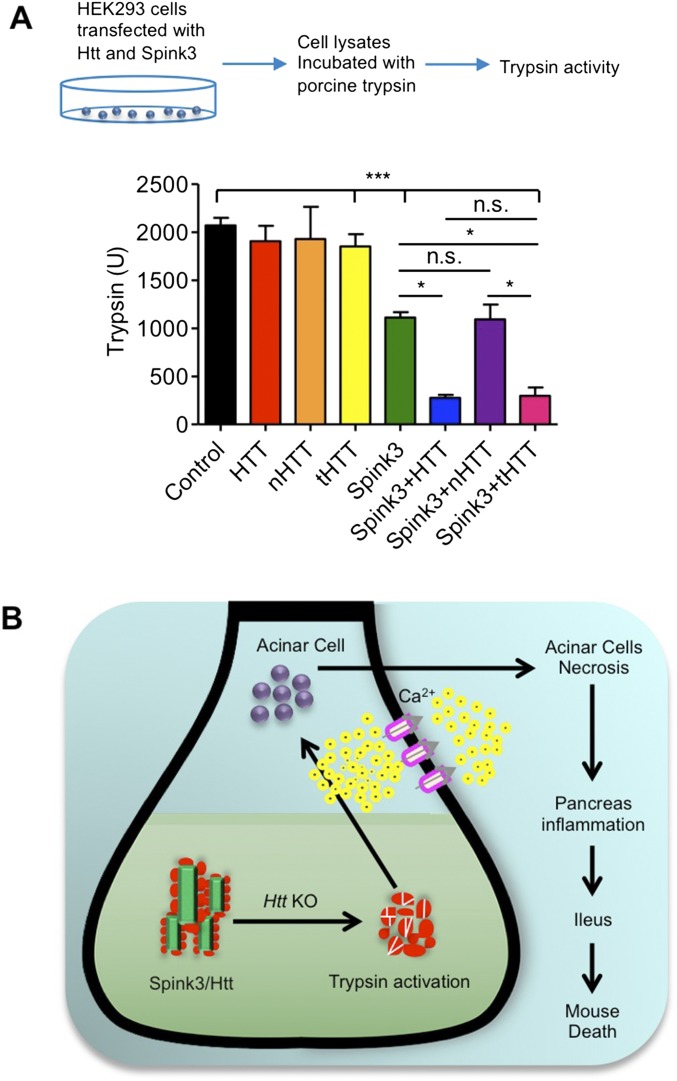

To verify the functional relevance of this binding, we transfected a series of Htt and Spink3 constructs into primary cultured acinar cells from ubiquitous KO mice. The cells were treated with tamoxifen (KO) to deplete endogenous Htt and then transfected with full-length HTT (fHTT), N-terminal HTT (1–208 aa, nHTT), or truncated HTT (tHTT) lacking N-terminal 169 amino acids. Measuring trypsin activities of these transfected cells revealed that fHTT and tHTT, but not nHTT, could restore the inhibitory function of Htt on trypsin activity when endogenous Htt has been depleted (Fig. 5D). We also performed transfection of HEK293 cells with a series of HTT and Spink3 constructs. Without overexpression of Spink3 and HTT, HEK293 cell lysates show detectable trypsin activity when incubated with porcine trypsin and the substrate Boc-Gln-Ala-Arg-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC). This activity was inhibited by expressing Spink3 and could be further reduced when additional tHTT was also expressed (Fig. S5A). However, nHTT was unable to promote this inhibition, supporting the idea that a truncated HTT lacking the N-terminal region is able to bind Spink3 to inhibit trypsin activity.

Fig. S5.

Interaction of Htt with Spink3 regulates trypsin activity in vitro. (A) Measurement of trypsin activity in vitro by adding Spink3, HTT, nHTT, tHTT, or Spink3 and HTT, nHTT, and tHTT containing cell lysates of transfected HEK293 cells. Cell extracts were mixed with porcine trypsin (TRSEQII) and the substrate Boc-Gln-Ala-Arg-AMC, and the rates of fluorescent products generated by trypsin were measured. Results are indicated as means ± SEM (n = 3; two-way ANOVA test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. (B) A model for Htt’s function in acinar cells. Htt binds Spink3 to inhibit trypsin activity in the pancreatic tissues in young mice. Loss of Htt will remove this inhibition, leading to trypsin activation in acinar cells and resulting in acinar cell degeneration and pancreas inflammation, as well as early death.

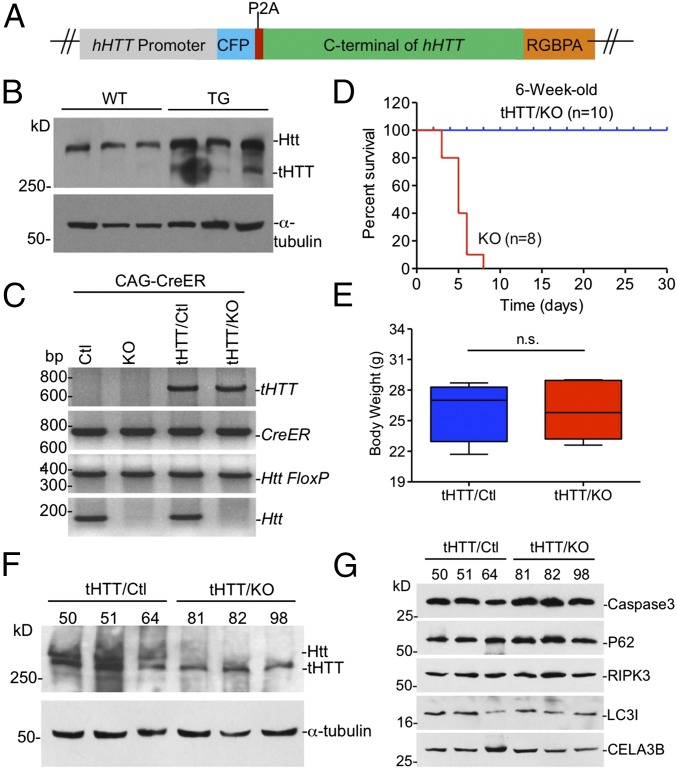

Transgenic tHTT Rescues the Early Death of Ubiquitous KO Mice.

We have generated transgenic mice that express tHTT lacking N-terminal 169 amino acids under the control of the human HTT promoter (Fig. 6 A and B). Because we have found that tHTT is able to bind Spink3 (Fig. 5C), we wanted to see if this transgenic HTT could rescue the acute pancreatitis and early death of ubiquitous KO mice. Thus, we crossed tHTT transgenic mice with ubiquitous KO mice. PCR genotype indicates that the transgenic tHTT existed in the crossed mice (Fig. 6C). The crossed mice were then injected with tamoxifen at the age of 6 wk to deplete the endogenous full-length Htt in mice. Mice carrying the transgenic tHTT, however, continued to live versus the ubiquitous KO mice that did not express transgenic tHTT (Fig. 6D). After depleting endogenous Htt for 5 mo, examination of the body weight of mice also revealed that these KO mice expressing tHTT (tHTT/KO) are indistinguishable from control mice (Fig. 6E). We then isolated the pancreatic tissues from tHTT/KO mice to perform Western blotting, which showed the expression of tHTT that is smaller than the endogenous full-length Htt in wild-type mouse pancreatic tissues (Fig. 6F). Moreover, the proteins for apoptosis (cleaved caspase3), necrosis (RIP3), autophagy (P62, LC3I/II), and CELA3B enzyme showed no alteration compared with those in the control mouse pancreatic tissues (Fig. 6G). Thus, this in vivo rescue effect also supports the idea that Htt is important for preventing pancreatic inflammation in young mice. Based on the results we obtained, we propose a model for the acute pancreatitis caused by the loss of Htt in young mice (Fig. S5B). In the pancreatic tissues of young mice, Htt binds Spink3 to help inhibit trypsin activity. Without Htt, this inhibition is abolished, leading to trypsin activation in acinar cells and resulting in acinar cell degeneration and pancreas inflammation, as well as early death. This function is not only cell-type specific but also age dependent, as aging increases the expression of Spink3, whose inhibitory effect on trypsin may also be dependent on other age-related factors.

Fig. 6.

Rescued effect of transgenic tHTT on Htt KO-induced pancreatitis. (A) tHTT construct used for generation of the tHTT transgenic mice. (B) Western blotting showing that tHTT is expressed in the mouse brain cortex. Wild-type mice cortex was used as control. (C) PCR genotyping verified the presence of transgenic tHTT in heterozygous (tHTT/Ctl) and homozygous (tHTT/KO) ubiquitous KO mice that also carry CAG-CreER. Ctl, control. (D) Survival rate of tHTT/KO mouse and ubiquitous KO mice showing that tHTT can prevent early death. (E) Body weight was tested at the fifth month after tamoxifen injection in the tHTT/KO and control (tHTT/Ctl) mice (paired two-tailed t test; n.s. represents no significant difference, n = 8, tHTT/KO, male = 5, female = 3; control, male = 4, female = 4). (F) Western blotting showing that tHTT is expressed in the ubiquitous KO mouse pancreas; heterozygous KO mouse pancreas was used as control. Note tHTT is smaller than full-length Htt (Htt). Three mouse pancreases of each genotype were examined. (G) Western blotting of the CELA3B, caspase-3, P62, RIPK3, and LC3I/II protein in the 2-mo-old tHTT/KO and control mouse pancreas.

Discussion

HTT is known to be essential for early embryonic development, and conditional knockout of Htt during the postnatal stage can also cause neurodegeneration (16). Interestingly, mutant HTT with expanded polyQ can rescue this embryonic lethality (27, 28). Deletion of polyQ or the proline-rich domain does not affect mouse development (29, 30). Also, humans homozygous for mutant expanded polyQ HTT age to adulthood with no obvious enhancement in pathology (31, 32), indicating that the expansion or lack of polyQ does not affect early development, but polyQ expansion causes late-onset neurodegeneration and neurological symptoms. Based on these findings, great efforts have gone into suppressing the expression of mutant HTT in the treatment of HD (13–15). Nevertheless, because of the essential function of HTT, a major concern has always been the possible side effects of depleting HTT. Our studies suggest that such concerns may be allayed if depletion of HTT occurs only in the brain or in older adults.

The previous studies using CaMKII-driven Cre transgenic mice show the degeneration of some neuronal cells and the degree of the degeneration appears to depend on age; the later depletion of Htt yielded a lesser extent of neuronal degeneration (16). Thus, Htt function in the brain appears to be age dependent, although its role in developing neuronal cells has been clearly shown by a number of studies (17, 33–35). Our studies show that in adulthood, Htt knockout does not affect neuronal survival or cause any significant movement or behavioral phenotypes. This finding is also supported by mice with selectively depleted Htt expression in the brain via Nestin-CreER or CaMKII-CreER. It should be pointed out that a few Nestin-Cre/KO mice die early, which is likely due to the expression of Cre in pancreatic acinar cells driven by the Nestin promoter (36). Thus, our studies suggest that depletion of HTT in adult brain would not cause severe phenotypes as seen in early development, providing a rationale to design a more efficient strategy to completely eliminate the expression of mutant HTT in adults.

Our findings also show that the interaction of Htt with Spink3 is important for preventing acute pancreatitis at young ages. Spink3 is the mouse homolog of serine protease inhibitor Kazal-type 1 (SPINK1) in humans, which is expressed at high levels in the pancreas (37, 38). SPINK1 is involved in pancreatitis in humans (24, 39, 40), as patients heterozygous for a SPINK1 mutation have a 20- to 40-fold increased risk of developing pancreatitis (23, 26, 41, 42), and this risk may be as high as 500-fold in individuals with homozygous mutations (26). However, germ-line knockout of the mouse Spink3 does not lead to acute pancreatitis but autophagic death of pancreatic acinar cells, although the homozygous KO mice die postnatally. This difference could be due to the species- and age-dependent role of Spink3 in mouse, as Spink3 also plays important roles in the proliferation and/or differentiation of various cell types during mouse development (43). Indeed, a progressive degradation of the exocrine pancreas is seen at 16.5 days postcoitus in Spink3 KO mice, which was attributed to autophagic cell death (44). However, in adult mice, the expression level of Spink3 appears to be important for acute pancreatitis, because transgenic expression of pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor-1 rescues Spink3-deficient mice and restores a normal pancreatic phenotype (45).

Another issue is why the loss of Htt-mediated death is age dependent. We saw that Spink3 is expressed at a lower level in pancreatic tissues in young mice. We also show that Htt binds more Spink3 at younger ages. These results suggest that the association of Htt with Spink3 is particularly important for Spink3 to inhibit trypsin activities when Spink3 is at a low level in pancreatic acinar cells at young ages. In older mice, the higher levels of Spink3 could be due to its interaction with other proteins, which may substitute the function of Htt.

Our studies suggest that Htt possesses a cell type-specific function that is also age dependent, adding more complexity to this large protein. Although this is somewhat surprising, it is reasonable given that Htt associates with so many proteins (46, 47). It is also known that mutant Htt with expanded polyQ repeats could cause a loss of function. For example, polyQ expansion can inhibit the normal function of Htt by altering its interactions with other proteins. Such consequence could be different from the complete loss of normal Htt, as the complete loss of HTT may be compensated by other molecules, whereas a partial loss of normal function of htt due to polyQ expansion may also affect the function of other proteins. The compensatory mechanisms for the loss of Htt may be cell-type and age dependent and can confound the interpretation of the function of Htt and the absence of overt phenotypes in adult mice that lack Htt. Despite further studies being required to understand the cell type-specific function of Htt, our results provide evidence for the first time to our knowledge that depletion of Htt causes cell type- and age-dependent phenotypes and also indicate the safety for a more efficient way of depleting neuronal HTT in adult brain to achieve better treatments for HD.

Materials and Methods

Htt floxP-flanked mice were provided by Scott Zeitlin, University of Virginia, Charlottsville, VA, and were maintained at the Emory University Animal Facility in accordance with the institutional animal care and use committee guidelines. All animal procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Emory University. Additional information is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Mouse Lines and Tamoxifen Injection.

All mice were maintained and bred in the Division of Animal Resources at Emory University on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. The mouse housing environment is specifically pathogen-free in accordance with institutional guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Emory University. Animal use followed the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The animal use protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) at Emory University. The Htt floxP-flanked mice were generated as previously described (16). To generate inducible ubiquitous knockout mice, we crossed Htt floxP-flanked mice with B6.Cg-Tg [(CAG-cre/Esr1)5Amc/J; The Jackson Laboratory] transgenic mice that express tamoxifen-inducible Cre throughout the body to generate homozygous Htt-floxed mice that also express Cre. We then i.p. injected tamoxifen into these homozygous mice for 5 consecutive days. To generate neuronal Htt knockout mice, we injected tamoxifen into homozygous Htt floxP-flanked mice with C57BL/6-Tg(Nes-cre/Esr1*)1Kuan/ (The Jackson Laboratory) transgenic mice, in which CreER fusion protein is expressed in neuronal cells under the control of the rat Nestin (Nes) promoter. To generate the forebrain Htt knockout mice, the homozygous Htt floxP-flanked mice with B6;129S6-Tg(Camk2a-cre/ERT2)1Aibs/J (The Jackson Laboratory) that express tamoxifen-inducible Cre driven by the mouse CaMKII (calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alpha) promoter region were injected with tamoxifen for 5 d. To generate tHTT transgenic mice [C57BL/6-Tg(tHTT)], we fused the truncated HTT cDNA encoding 170–3,141 amino acids of human Htt to ECFP, P2A, and RGBPA genes in a vector. The resulting construct expresses tHTT under the control of human HTT gene promoter. Microinjection of linearized construct into SV129/B6 mouse embryos was conducted by the Emory University Transgenic Mouse Core Facility to generate transgenic tHTT mice [C57BL/6-Tg (tHTT)]. To generate the tHTT transgenic/Htt ubiquitous KO mouse, the tHTT mice were crossed with homozygous floxed Htt/CAG-CreER mice that also contained the transgenic CAG-CreER gene and bred to homozygous Htt-floxed mice with Cre and tHTT transgene expression. The resulting crossed transgenic mice would deplete endogenous Htt expression upon tamoxifen injection, while expressing transgenic tHTT.

Genomic DNAs used for PCR genotyping from all mouse models were isolated by DirectPCR Lysis Reagent (tail) (cat. no. 102-T). Primers were used for genotyping of the wild-type Htt (forward, 5′-CTA AAG CGC ATG CTC CAG ACT G-3′; reverse, 5′-AGA TCT TGG CTG AGT TAT AGG TCA GC-3′), Htt floxP (forward, 5′-CAT TTG ATT CTT ACA GGT AGC CTG -3′; reverse, 5′-AGA TCT TGG CTG AGT TAT AGG TCA GC-3′), and Cre positive (forward, 5′-GCG GTC TGG CAG TAA AAA CTA TC-3′; reverse, 5′-TGT TTC ACT ATC CAG GTT ACG G-3′). Primers were used for genotyping of transgenic tHTT as follows: forward, 5′-ATC TGT CGA CGG CAC CAT GGT GAG CAA GGG CGA GGA G-3′; reverse, 5′-ACC AAG CTT CTC CAG TTT GTC ATC GTC ATC CTT GTA GTC-3′.

For injection of tamoxifen into the mice, tamoxifen purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (T5648) was dissolved in 100% ethanol as stock solution at 20 mg/mL. A calculated amount of tamoxifen was mixed thoroughly with corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich, C8267), and the ethanol was removed by Vacufuge plus (Eppendorf). Tamoxifen that had been dissolved in corn oil was injected intraperitoneally into mice at 0.1 mg per 1 g body weight for 5 consecutive days.

Plasmids and Antibodies.

The shRNA plasmids were used to knock down HTT (siHTT13) and GFP (siGFP) as described previously (48). The DNAs for rabbit beta globin PolyA (RBGP), human HTT promoter, mouse Spink3, ECFP coding region, and P2A were generated by PCR. Primers used were as follows: HTT promoter (forward, 5′-ACG GTA CCT TAA TTA ACA ACT GCA CAC AGT CAT CTG GG-5′; reverse, 5′-ATC AGT CGA CAG GGT GCC CTT GGC GGT CT-3′); RBGP (forward, 5′-ATG AAT TCG CGG CCG CAG GTA GCA GAT CTT TTT CCC TCT GC-3′; reverse, 5′-ATC CCG CGG TTA ATT AAT TGA TAA GAG AAG AGG GAC A-3′); ECFP (forward, 5′-ATT CTC GAG GGC ACC ATG GTG AGC AAG GGC GAG GAG-3′; reverse-1, 5′-GTC CAG GGT TCT CCT CCA CGT CTC CAG CCT GCT TCA GCA GGC TGA AGT TAG TAG CTC CGC TTC CTC CGG ACT TGT ACA GCT CGT G-3′; reverse-2, 5′-ACC CTC GAG TTT GTC ATC GTC ATC CTT GTA GTC TTT GTC ATC GTC ATC CTT GTA GTC CAT AGG TCC AGG GTT CTC CTC C-3′); mouse Spink3 (forward, 5′-ATG GAT CCG CGA CAA TG A AGG TGG CTG TCA TCT TTC TTC TCA G-3′; reverse, 5′-TGA ATT CGC AAG GCC CAC CTT TTC GAA TGA G-3′). N-Spink3 (1–45) (forward, 5′-ACA TCT CGA GAT GAA GGT GGC TGT CAT CTT TC-3′; reverse, 5′-GTC GGA ATT CAT CAT AAA TTC TGG GAC ATC C-3′); C-Spink3 (33–80) (forward, 5′-AAC TCT CGA GTG CCA TGA TGC AGT GGC GGG AT-3′; reverse, 5′-TGC CGA ATT CGC AAG GCC CAC CTT TTC GAA TG-3′). The PCR products of HTT promoter were digested by KpnI and SalI, and RBGP were digested by EcoRI and SacII DNA construction. The ECFP PCR products were digested by SalI and HindIII, the truncated HTT was released from full-length HTT plasmids by XhoI and NotI digestion. The digested DNA products were cloned to pBluescriptSK(−) vector to generate ECFP-P2A-tHTT that expresses tHTT under the control of human HTT promoter. This tHTT construct was used for pronuclear injection to generate transgenic mice by the Transgenic Core Facility at Emory University. The Spink3 DNA fragments were digestion by BamHI and EcoRI and then cloned into pRK5 mammalian expression vector. The N-Spink3(1–45) and C-Spink3(33–80) PCR fragments were digestion by XhoI and EcoRI and inserted into pEGFP-C3 vector. The full-length HTT plasmid pEBV-HTT-23Q was constructed as described previously (49).

Rabbit antibodies used in this study were obtained from commercial sources as follows: HTT [EPR5526] (Abcam), beta-tubulin III [EP1569Y] (Novus Biologicals), NF-κB [D14E12] (Cell Signaling), LC3I/II [NB100-2220] (Novus Biologicals), ELA3B [GTX105123] (GeneTex), FAT10 [EPR4370] (GeneTex), SPINK3 [2744S] (Cell Signaling), HA [C29F4] (Cell Signaling), p-NF-κB [93H1] (Cell Signaling), RIP3 [GTX107574] (GeneTex), Caspase3 [9662] (Cell Signaling), and cleaved Caspase3 [5A1E] (Cell Signaling). Mouse antibodies were used in this study as follows: HTT [MAB2166] (Millipore), alpha-tubulin [T5168] (Sigma Aldrich), beta-actin [SC-47778S] (Santa Cruz), P62 [ab56416] (Abcam), GAPDH [MA1-10036] (Thermo Scientific), NeuN [MAB377] (Millipore), GFAP [MAB3600] (Millipore), INSULIN [MAB1417] (R&D Systems), GFP [E022030-01] (EARTHOX), and GFP [GT859] (GeneTex). All secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories.

Behavioral Studies.

The body weight of mouse pups was measured every day from birth to 2 mo old. After tamoxifen injection, the body weight of mice was measured every month for 5 consecutive months.

For motor function assay, mice (10–15 per group) were assessed by a Rotamex 4/8 (Columbus Instruments International) every month. Before the test, mice were trained on the rotarod at the speed of 5 rpm for 20 min for 3 consecutive days. For testing, the speed of the rotarod was set to accelerate from 0 rpm to 40 rpm, with the increment of 0.1 rpm per second. Mice were allowed to rest for 20 min between trials. Each mouse was subjected to three trials, and the time was recorded automatically by the machine. The average time of three trials was used to evaluate the motor activity of the mice.

For the gripping ability test, mice were measured by grip strength meters (Columbus Instruments International) every month. Before the initial test, mice were trained for 3 consecutive days. During the test, the grip strength meters were set to zero, a mouse was placed on the wire netting to let it firmly grasp the meter, and the same strength was used to pull the mouse tail. The data were recorded automatically by the machine, and each mouse was tested three times. The average strength of three trials was used to evaluate the gripping ability of the mice.

Brain Volume.

The brain volume was measured by skull volume; the skull volume was filled with water and the mouse brain was added to the container. The water overflow from the container was then measured by a volumetric cylinder.

Cell Culture.

Human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 µg/mL amphotencin B. The cell line was purchased from ATTC and the cell lines were cultured in compliance with the US Public Health Service Guidelines.

Primary mouse acinar cells were cultured as described previously (50). Before seeding, six-well culture dishes were coated with type I collagen (5 μg/cm2) by adding 1 mL of type I collagen solution (50 μg/mL in 0.02 M acetic acid, 0.2 μm filtered) to each well. After discarding the collagen solution, the coated wells were washed twice with 1× PBS and dried at least 12 h before use.

All procedures for isolating acinar cells were performed under a sterile atmosphere. For mouse pancreas dissection, mice were killed by cervical dislocation and fixed on the flat wooden board. The isolated pancreatic tissues were rinsed twice with 1× Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) without calcium ion Ca2+ chelators. The pancreas was sliced to small pieces of 2 mm3 using a Noyes scissors and a scalpel. The sliced pancreas was transferred into a 50-mL polypropylene tube followed by centrifugation at 450 × g for 2 min in 4 °C. After discarding the supernatant to remove cell fragments and blood cells, 10 mL of collagenase IA solution (1× HBSS containing 10 mM Hepes, 200 units/mL of collagenase IA, and 0.25 mg/mL of trypsin inhibitor) were added to pancreas sections, which were then transferred to a 25-cm2 flask for incubation for 20–30 min at 37 °C. During this time (every 5 min), a mechanical dissociation was performed by energetically moving back and forth the pancreas fragments about 10 times. After dissociation, the enzymatic reaction was stopped by adding 10 mL of cold washing buffer (HBSS 1× containing 5% FBS and 10 mM Hepes). The dissociated pancreatic tissues were transferred into a sterile 50-mL polypropylene tube and centrifuged for 2 min at 450 × g at 4 °C. The pellets were resuspended and washed with 10 mL of buffered washing solution.

After washing, the cell pellets were resuspended in 7 mL of Waymouth's medium containing 2.5% (vol/vol) FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin mixture (PS), 0.25 mg/mL of trypsin inhibitor, and 25 ng/mL of recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF). The cell mixture was filtrated by passing through a 100-μm filter to retain the nondigested fragments while pancreatic acinar structures (acinus of 10–15 cells) could pass through. The isolated acini were seeded as 2 mL per well in a six-well culture dish and then cultured at 37 °C under 5% (vol/vol) CO2. After culturing for 24 h, the cells were used for DNA transfection.

H&E Staining.

For H&E staining the mouse tissues, the tissues were isolated after mice were anesthetized with 5% chloral hydrate. Mouse tissues were fixed in the 10% neutral buffered formalin (4% neutral buffered formaldehyde) overnight, embedded in paraffin, and then sectioned to 5 µm by Winship Core–Pathology Core Laboratory at Emory University.

Western Blot, Immunofluorescence, Immunohistochemistry, Coimmunoprecipitation, and Electron Microscopy.

For Western blot, protein samples were homogenized in the Nonidet P-40 buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% Nonidet P-40) or RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, pH 8.0, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% DOC, and 1% Triton X-100) with 1× protease inhibitor (Sigma, P8340). The amount of protein loaded was determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (23225). The lysates were run in a Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen) and blotted to a nitrocellulose membrane. Blots were analyzed using relative antibodies specific for different proteins. Proteins on the blot were visualized by using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (34095) or Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (RPN2232) for Western blotting.

For immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry, mice were anesthetized and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.01 M PBS. The isolated brain, pancreatic, and other tissues were fixed overnight (12–16 h) in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.01 M PBS, and then transferred into 30% sucrose at 4 °C to let the brain completely sink to the bottom of the tube. The brains or other tissues were sectioned at 20 μm with a cryostat at −19 °C. Mice tissue slides or cultured cells were fixed for 12 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.01 M PBS at room temperature, blocked with 0.1% Triton X-100/3% BSA/1× PBS for 30 min, and incubated with primary antibodies to relative proteins in 3% BSA/1× PBS overnight at 4 °C. The slices were washed three times with 1× PBS and rinsed with specific donkey anti-mouse, -rabbit, or -goat fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch) and Hoechst for staining nuclear that was diluted in 1× PBS for 2 h at room temperature. The mouse tissue sections were examined by using a Zeiss (Axiovert 200M) microscope with a digital camera (Orca-100; Hamamatsu Photonics) and Openlab software (Improvision).

For coimmunoprecipitation, the Nonidet P-40 buffer (50 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.0, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1.0% Nonidet P-40) was used to homogenize the mouse tissues and culture cells. Protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, 23227) and 2,000 µg of protein was used for one experiment. About 30 µl Protein A-beads (Sigma) were used to preclean the protein lysates for 2 h. The immunocomplexes were washed three times in ice-cold lysis buffer, eluted by boiling in 1× SDS loading buffer, and then analyzed for Western blotting.

For electron microscopy, the mice were perfused with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (PB, pH = 7.3) containing 4% PFA and 0.2% glutaraldehyde. Details for electron microscopic examination were described previously (12).

Enzyme Activity Assay.

Mice were killed at intervals between 30 and 48 h after the 2 or 3 i.p. injection of tamoxifen. The sera of blood were isolated by centrifuging at 10,000 × g for 2 min, and the upper layer sera were stored at −80 °C for further studies. For measurement of pancreatic enzyme activities, pancreatic tissues were thawed and homogenized in iced buffer containing 5 mM MOPS, 1 mM MgSO4, and 250 mM sucrose (pH 6.5). Sample preparation for trypsin, trypsinogen activation peptide (TAP), and MPO assay was performed as described previously (51). The amylase and lipase activities were determined by commercially available kits (DLPS-100 and DAMY-100) (BioAssay System).

In Vitro Trypsin Activity Assay.

The trypsin activities were determined with a fluorescent assay using a spectrophotometer in which samples were excited at 380 nm and emissions were collected at 440 nm for a minimum of 5 min. The substrate Boc-Gln-Ala-Arg-MCA was added to the cell lysates, which was digested by trypsin, resulting in a fluorescent dye called MCA (7-amino-4-methylcoumarin) that can be detected via fluorescence intensity.

Mouse pancreas tissues were homogenized by using a Teflon homogenizer for 50 strokes and sonicated for 10 s on ice in homogenization buffer (pH 6.5, 5 mM MOPS, 250 mM sucrose, and 1 mM magnesium sulfate). The lysates were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 5 min, and the supernatants were used for trypsin assay. To determine tissue or cell protein concentration, a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (23225) was used with the absorbance value at 562 nm. A final working concentration of 50 μM trypsin substrate Boc-Gln-Ala-Arg-MCA was dissolved in assay buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mg/mL BSA. The mixture (285 μL 50 μM Boc-Gln-Ala-Arg-MCA and 15 μL of cell lysate supernatants) was added into the 96-well microplate, allowing the cleavage of the substrate by trypsin at 37 °C for 30 min. A standard curve was generated using commercial porcine trypsin (Sigma, T8003) in different concentrations (0–10,000 units).

For in vitro trypsin activity assay of cultured HEK293 cells transfected with different Spink3 and HTT forms, 15 μL cell lysate supernatants was mixed with 10 μL 2,000 units porcine trypsin (Sigma, T8003) and 275 μL 50 μM trypsin substrate Boc-Gln-Ala-Arg-MCA and then used for trypsin assay as mentioned above.

Statistics Analysis.

Unless stated otherwise, values in figures and text are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel Student's t test (two tailed) and Prism (GraphPad Software). For comparing two different groups, the Microsoft Excel Student's t test (two tailed) was used for analysis. For behavioral data analysis, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), which was followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001, respectively, represent statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Scott Zeitlin for providing floxed Htt KO mice, Heju Zhang at the Transgenic Mouse/Gene Targeting Core Facility at Emory University for generating transgenic mice, Dr. Hong Yi of the Robert P. Apkarian Integrated Electron Microscopy Core at Emory University for help with electron microscopy, and Cheryl Strauss for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 91332206, National Institutes of Health Grants NS041669 and AG019206 (to X.-J.L.) and NS095279 (to S.L.), and the State Key Laboratory of Molecular Developmental Biology, China.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1524575113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ross CA, et al. Huntington disease: Natural history, biomarkers and prospects for therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(4):204–216. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Paola M, et al. MRI measures of corpus callosum iron and myelin in early Huntington’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(7):3143–3151. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoffers D, et al. Contrasting gray and white matter changes in preclinical Huntington disease: An MRI study. Neurology. 2010;74(15):1208–1216. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d8c20a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuccato C, Cattaneo E. Huntington’s disease. Handbook Exp Pharmacol. 2014;220:357–409. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-45106-5_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasir J, et al. Targeted disruption of the Huntington’s disease gene results in embryonic lethality and behavioral and morphological changes in heterozygotes. Cell. 1995;81(5):811–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duyao MP, et al. Inactivation of the mouse Huntington’s disease gene homolog Hdh. Science. 1995;269(5222):407–410. doi: 10.1126/science.7618107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeitlin S, Liu JP, Chapman DL, Papaioannou VE, Efstratiadis A. Increased apoptosis and early embryonic lethality in mice nullizygous for the Huntington’s disease gene homologue. Nat Genet. 1995;11(2):155–163. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heng MY, Detloff PJ, Albin RL. Rodent genetic models of Huntington disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;32(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JM, et al. Dominant effects of the Huntington’s disease HTT CAG repeat length are captured in gene-expression data sets by a continuous analysis mathematical modeling strategy. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(16):3227–3238. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crook ZR, Housman D. Huntington’s disease: Can mice lead the way to treatment? Neuron. 2011;69(3):423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang D, et al. Expression of Huntington’s disease protein results in apoptotic neurons in the brains of cloned transgenic pigs. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(20):3983–3994. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Q, et al. Synaptic mutant huntingtin inhibits synapsin-1 phosphorylation and causes neurological symptoms. J Cell Biol. 2013;202(7):1123–1138. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201303146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Southwell AL, Patterson PH. Gene therapy in mouse models of huntington disease. Neuroscientist. 2011;17(2):153–162. doi: 10.1177/1073858410386236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Friedlander RM. Using non-coding small RNAs to develop therapies for Huntington’s disease. Gene Ther. 2011;18(12):1139–1149. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aronin N, DiFiglia M. Huntingtin-lowering strategies in Huntington’s disease: Antisense oligonucleotides, small RNAs, and gene editing. Mov Disord. 2014;29(11):1455–1461. doi: 10.1002/mds.26020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dragatsis I, Levine MS, Zeitlin S. Inactivation of Hdh in the brain and testis results in progressive neurodegeneration and sterility in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;26(3):300–306. doi: 10.1038/81593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White JK, et al. Huntingtin is required for neurogenesis and is not impaired by the Huntington’s disease CAG expansion. Nat Genet. 1997;17(4):404–410. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashimoto D, et al. Involvement of autophagy in trypsinogen activation within the pancreatic acinar cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;181(7):1065–1072. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaisano HY, Gorelick FS. New insights into the mechanisms of pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(7):2040–2044. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sah RP, Dawra RK, Saluja AK. New insights into the pathogenesis of pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29(5):523–530. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328363e399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegyi P, Rakonczay Z. Insufficiency of electrolyte and fluid secretion by pancreatic ductal cells leads to increased patient risk for pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(9):2119–2120. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohmuraya M, Hirota M, Araki K, Baba H, Yamamura K. Enhanced trypsin activity in pancreatic acinar cells deficient for serine protease inhibitor kazal type 3. Pancreas. 2006;33(1):104–106. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000226889.86322.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noone PG, et al. Cystic fibrosis gene mutations and pancreatitis risk: Relation to epithelial ion transport and trypsin inhibitor gene mutations. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(6):1310–1319. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witt H, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the serine protease inhibitor, Kazal type 1 are associated with chronic pancreatitis. Nat Genet. 2000;25(2):213–216. doi: 10.1038/76088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfützer RH, et al. SPINK1/PSTI polymorphisms act as disease modifiers in familial and idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(3):615–623. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.18017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keim V. Role of genetic disorders in acute recurrent pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(7):1011–1015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodgson JG, et al. A YAC mouse model for Huntington’s disease with full-length mutant huntingtin, cytoplasmic toxicity, and selective striatal neurodegeneration. Neuron. 1999;23(1):181–192. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80764-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray M, et al. Full-length human mutant huntingtin with a stable polyglutamine repeat can elicit progressive and selective neuropathogenesis in BACHD mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28(24):6182–6195. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0857-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng S, et al. Deletion of the huntingtin polyglutamine stretch enhances neuronal autophagy and longevity in mice. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(2):e1000838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neveklovska M, Clabough EB, Steffan JS, Zeitlin SO. Deletion of the huntingtin proline-rich region does not significantly affect normal huntingtin function in mice. J Huntingtons Dis. 2012;1(1):71–87. doi: 10.3233/JHD-2012-120016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wexler NS, et al. Homozygotes for Huntington’s disease. Nature. 1987;326(6109):194–197. doi: 10.1038/326194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myers RH, et al. Homozygote for Huntington disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;45(4):615–618. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Godin JD, et al. Huntingtin is required for mitotic spindle orientation and mammalian neurogenesis. Neuron. 2010;67(3):392–406. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong Y, et al. Spatial and temporal requirements for huntingtin (Htt) in neuronal migration and survival during brain development. J Neurosci. 2011;31(41):14794–14799. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2774-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haremaki T, Deglincerti A, Brivanlou AH. Huntingtin is required for ciliogenesis and neurogenesis during early Xenopus development. Dev Biol. 2015;408(2):305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delacour A, Nepote V, Trumpp A, Herrera PL. Nestin expression in pancreatic exocrine cell lineages. Mech Dev. 2004;121(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greene LJ, Pubols MH, Bartelt DC. Human pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor. Methods Enzymol. 1976;45:813–825. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(76)45075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graf R, Bimmler D. Biochemistry and biology of SPINK-PSTI and monitor peptide. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2006;35(2):333–343, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen JM, Mercier B, Audrezet MP, Ferec C. Mutational analysis of the human pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (PSTI) gene in hereditary and sporadic chronic pancreatitis. J Med Genet. 2000;37(1):67–69. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liddle RA. Pathophysiology of SPINK mutations in pancreatic development and disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2006;35(2):345–356, x. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Reilly DA, et al. The SPINK1 N34S variant is associated with acute pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20(8):726–731. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f5728c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tukiainen E, et al. Pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (SPINK1) gene mutations in patients with acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2005;30(3):239–242. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000157479.84036.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, et al. Expression pattern of serine protease inhibitor kazal type 3 (Spink3) during mouse embryonic development. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130(2):387–397. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohmuraya M, et al. Autophagic cell death of pancreatic acinar cells in serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 3-deficient mice. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(2):696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romac JM, et al. Transgenic expression of pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor-1 rescues SPINK3-deficient mice and restores a normal pancreatic phenotype. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298(4):G518–G524. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00431.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shirasaki DI, et al. Network organization of the huntingtin proteomic interactome in mammalian brain. Neuron. 2012;75(1):41–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li SH, Li XJ. Huntingtin and its role in neuronal degeneration. Neuroscientist. 2004;10(5):467–475. doi: 10.1177/1073858404266777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drouet V, et al. Sustained effects of nonallele-specific Huntingtin silencing. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(3):276–285. doi: 10.1002/ana.21569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhat KP, Yan S, Wang CE, Li S, Li XJ. Differential ubiquitination and degradation of huntingtin fragments modulated by ubiquitin-protein ligase E3A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(15):5706–5711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402215111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gout J, et al. Isolation and culture of mouse primary pancreatic acinar cells. J Vis Exp. 2013 doi: 10.3791/50514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halangk W, et al. Role of cathepsin B in intracellular trypsinogen activation and the onset of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(6):773–781. doi: 10.1172/JCI9411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]