CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

In a 2012 AJPE statement, a group of pharmacy school deans asked the question, “Are we producing innovators and leaders, or change resisters and followers?” They called upon AACP to lead an Academy-wide assessment of current admissions, recruitment and interview practices to assess their effectiveness in identifying the innovators and leaders for the future. Further, they encouraged individual members and member schools to undertake scholarship on the types of skills needed to become successful leaders in the practice of pharmacy.1

According to the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree, admissions criteria should support the potential of the student to become an effective professional and a self-directed lifelong learner. The ACPE Standards and Guidelines state in Guideline 17.3 that admissions criteria should take into account other desirable qualities, “such as intellectual curiosity, leadership, emotional maturity, empathy, ethical behavior, motivation, industriousness, and communication capabilities.”2

Marketplace factors in the evolution of healthcare and pharmacy practice are impacting pharmacy school admissions and will continue to influence this process for the foreseeable future. A plateau in the number of applications to schools of pharmacy, as well as increased competition for qualified applicants among the growing number of schools, are among the factors impacting admissions.

The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) 2013-2015 Special Committee on Admissions was charged to:

• examine current admissions practices used by pharmacy schools

• evaluate innovative practices used by other health professions

• make recommendations as to how schools may holistically assess at admissions the types of learners who will become the confident practice-ready graduates and future leaders/innovators the profession needs

The committee was encouraged to examine pre-pharmacy requirements, recruitment strategies, admissions requirements and strategic admissions practices, and support for evaluating and admitting non-traditional and international applicants.

BACKGROUND

Each school of pharmacy seeks to ensure students admitted into the professional program are prepared to meet the challenges of a rigorous curriculum and professional practice. To assist the Academy in meeting this goal, the AACP Special Committee on Admissions evaluated strategies used in pharmacy, as well as in other health professions for recruitment, admissions and innovation through holistic review.

Recruitment

The work necessary to ensure a quality applicant pool starts long before the pharmacy admissions cycle. Schools must ensure they are creating a pipeline of students interested in pursuing a career in pharmacy. While AACP has developed a number of tools aimed at recruiting individuals to the profession of pharmacy, the collective effort of all schools of pharmacy is needed to transform recruitment on a broad scale. The goal must reach beyond increasing application numbers. As White et al point out, schools of pharmacy must have a multifaceted approach that also targets specific populations (eg, students of a diverse background) to find success.3

Admissions

ACPE Standards 2016 state that each school of pharmacy must develop, implement, and assess its admission criteria, policies, and procedures to ensure the selection of a qualified and diverse student body (Standard 16).2 As part of its initial work, the Committee conducted a Call for Current Practices in Admissions to gather information on the policies and procedures utilized in different schools of pharmacy, specifically looking at assessment of pre-pharmacy competency, use of the Pharmacy College Admission Test (PCAT), and measurement of non-cognitive abilities. Respondents (n=28) indicated that pre-pharmacy competence was most often assessed by a combination of overall GPA, science GPA, math GPA, and/or (PCAT) composite and sub-scores. There were a number of other factors that were also considered, including credit load, institution where pre-pharmacy education was obtained, academic credit load, attainment of previous degree, number of withdrawals and repeat coursework.

Although the PCAT is designed to measure competency in core pharmacy prerequisites, it does not measure a student’s abilities in all academic areas (e.g. social sciences, non-cognitive characteristics). Since the PCAT captures a student’s academic ability at a single point in time, scores do not provide information on performance trends over time. Additionally, neither Pearson nor AACP establishes passing scores the overall PCAT composite score or for individual domains. The utilization of absolute cut points or minimum scores may unintentionally eliminate otherwise admirable candidates. PCAT scores should always be considered in combination with other information when evaluating applicants for admission.

The 2011-2012 Argus Commission, in their report, Cultivating 'Habits of Mind' in the Scholarly Pharmacy Clinician, recommended that colleges and schools of pharmacy identify the most effective validated assessments of inquisitiveness, critical thinking, and professionalism for use in admissions. The Commission recommended that pre-pharmacy requirements be minimized in favor of the aforementioned assessments and that pre-pharmacy experiences that develop an inquisitive mind be considered in admissions.4 In the 2009 report, Scientific Foundations of Future Physicians, AAMC and HHMI undertook similar steps by developing a broad set of competencies to define the knowledge and skills required for entry into medical school.5

While many schools are confident in their ability to assess pre-pharmacy academic competence, many schools report difficulty in assessing non-cognitive abilities and characteristics called for by the Argus Commission. Colleges and schools that did assess these abilities accomplished this through the interview process, personal statements, essays, interview day writing assignments, standardized critical thinking tests, applicant group problem solving, standardized questions used during the interview, and the Multiple Mini- Interview (MMI).

Respondents differed in the definition of holistic admissions and holistic review as well as the implementation of practices to assess non-cognitive characteristics. The survey identified a need for training and education in holistic review.

Innovation - Holistic Review

“Holism in assessment is a school of thought or belief system rather than a specific technique. It is based on the notion that assessment of future success requires taking into account the whole person. In its strongest form, individual test scores or measurement ratings are subordinate to expert diagnoses. Traditional standardized tests are seen as providing only limited snapshots of a person, and expert intuition is viewed as the only way to understand how attributes interact to create a complex whole. Expert intuition is used not only to gather information but also to properly execute data combination. Under the holism school, an expert combination of cues qualifies as a method or process of measurement. The holistic assessor views the assessment of personality and ability as an ideographic enterprise, wherein the uniqueness of the individual is emphasized and nomothetic generalizations are downplayed.”6

This belief system has been widely adopted in college admissions and is implicitly held by employers who rely exclusively on traditional employment interviews to make hiring decisions.7

Holistic review in admissions is a flexible, highly-individualized process by which balanced consideration is given to the multiple ways in which applicants may prepare for and demonstrate suitability as student pharmacists and future pharmacists. Under a holistic review framework, candidates are evaluated by criteria that are institution-specific, broad-based, and mission-driven and that are applied equitably across the entire applicant pool.8

Other health professions have been encouraging and providing guidance for the use of holistic admissions. The American Dental Education Association (ADEA) has implemented training workshops for admissions officers to assist with establishing holistic admissions practices to match the missions and values of their respective institutions. For example, Anne Wells, of the American Dental Education Association, highlighted several ways in which applicant experiences can provide evidence of work ethic and dedication, including community service, work and military experience (especially while attending school) and overcoming challenging life situations or economic hardship. The ADEA training program has been conducted throughout the United States to assist dental admissions officers in developing processes for reviewing dental applicants in a more holistic manner.

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) published a guiding document Roadmap to Diversity: Integrating Holistic Review Practices into Medical School Admission Processes.8 This publication provides schools with a flexible, modular framework and accompanying tools for aligning admission policies, processes, and criteria with an institution-specific mission and goals, and establishing, sustaining, and reaping the benefits of medical student diversity. The publication calls for evaluation of the outcomes of holistic review. The authors posit, “Conducting evaluation and sharing the findings provide medical schools the opportunity to demonstrate what holistic review is doing for the school in meaningful ways. Evaluating the effectiveness of admission policies, processes, and criteria in producing outcomes that reflect a medical school’s mission is a core element of holistic review.”8 The AAMC also created a training program to help admission deans, staff, and admission committees at medical schools develop and integrate holistic review practices into student selection processes.

The need for holistic review is imperative when seeking to admit well-rounded students who can make sound decisions and recommendations regarding safe, effective medication therapy in a caring, respectful manner to patients.

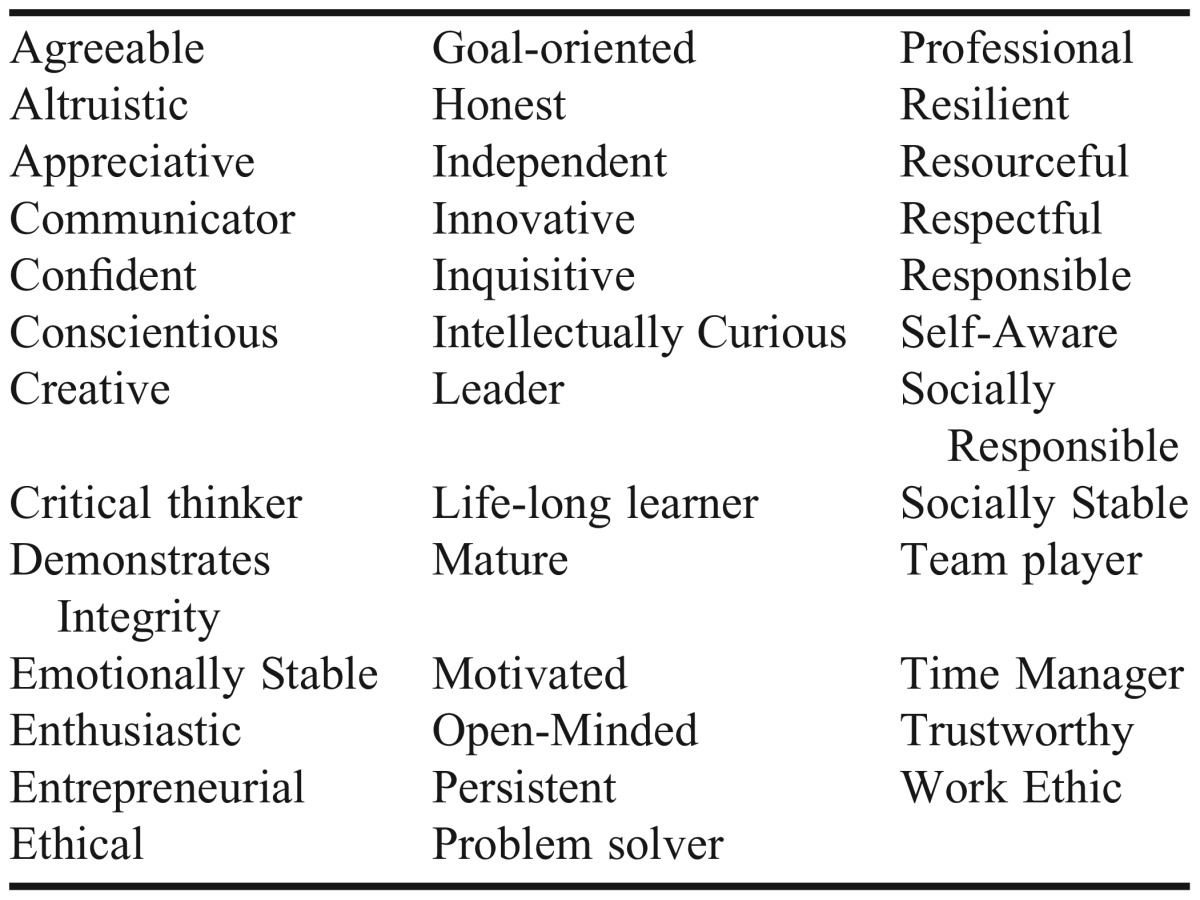

Characteristics or traits that have been considered throughout the literature, as well as in accreditation standards, and curricular and professional outcomes, to define more than academic performance or cognition are noted as non-cognitive, of the affective domain, or soft skills, and include, but are not limited to, those listed in Table 1. 2, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16

Table 1.

LITERATURE REVIEW

There is limited consistent evidence in the literature about admission factors that predict success in the pharmacy school curriculum. Although pharmacy school admissions officers often meet at conferences to share helpful information about admissions practices, these practices are not always supported by evidence in the literature. A literature search revealed little research that addresses the predictive validity of pharmacy school admissions criteria and processes on a national level. Current research addresses the topic at a local college/school level; however, these findings are not always transferable to other institutions.

There are many factors to consider when identifying admissions criteria that predict success. First, the role of the pharmacist defines what it means to be successful in pharmacy education and practice, and provides a foundation for the development of admissions criteria. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) sets the minimum standards and guidelines for pharmacy education in conjunction with stakeholders throughout the pharmacy profession to ensure that pharmacy graduates are prepared for practice.2 Every state requires that entry-level pharmacists graduate from an ACPE accredited institution, and as a result, ACPE standards serve as a cornerstone in identifying admissions criteria to predict success.

Secondly, the structure of the admissions process establishes criteria and factors each institution deems critical to success and reflects the college/school’s mission and goals. The degree to which cognitive or objective factors (e.g., previous degree, grade point average, standardized test scores) are considered relative to non-cognitive traits (e.g., maturity, motivation, determination, resilience) highlights factors related to success at individual programs. The nature of current practices across institutions provides an opportunity to examine the relationship between admissions criteria and success in pharmacy education and practice.

The third consideration in identifying predictive admissions criteria is current research. As indicated above, little research has been done on a national level regarding admissions factors to predict success. Current literature on academic performance and success has focused on cognitive skills and objective measures at single institutions and has largely defined success by grade point average. While some work has been done on non-cognitive skills (communication skills, interview performance, previous work experience), opportunities abound for additional research. Evidence related to predictors for clinical success is also limited. Research suggests that traditional admissions measures may not provide sufficient insight into the skills required for success at the doctoral level and are not predictive of the professional skills required in the health or helping professions. Finally, research suggests that the use of cognitive measures alone may be a barrier for diverse students and may exclude students with the non-cognitive traits associated with strong professional contributors (see Appendix A for citations).

Information is provided in two appendices as a resource and reference for admissions officers and committees as they study their own admissions process. Appendix A provides a comprehensive literature review and highlights opportunities for research at a national level on emerging considerations in pharmacy admissions. This review includes a summary of current research, discussion of research on cognitive and non-cognitive skills, predictive validity of cognitive measures and a summary of research related to holistic review as it relates to admissions and access to education. The statistical analysis models used in current research provide a framework for future studies. Appendix B provides a listing of tools used for assessment of non-cognitive factors in admissions. Appendix C provides a summary of admissions traffic guidelines used by other health professions as well as proposed Cooperative Admissions Guidelines for schools and colleges of pharmacy.

DISCUSSION

A number of trends have converged to make it imperative that schools and colleges bring more attention to their recruitment and admissions processes. These include 1) an increasing recognition of the value of diversity in the pharmacist workforce and thus in the classes we educate, 2) a tightening applicant pool, such that currently there is only a slight excess of applicants to seats in our classes, and 3) the movement among other health professions to move to holistic admissions policies in selecting who is admitted to health sciences programs.

The need for greater diversity in our classes and thus our workforce, grows out of the need to have pharmacists from diverse cultures that can provide culturally sensitive care to our increasingly diverse communities throughout the nation, and to help educate their non-minority classmates about the factors that optimize care to those communities. The data on health care disparities shows that the gap between the health care and health outcomes experienced by middle class, white citizens compared to those from lower economic and social classes, which are also often racial and ethnic minorities, are alarming and presents a grand challenge to the nation to solve. Additionally there is increasing evidence that a diverse group of decision-makers and problem-solvers results in better decision-making.17, 18

When there is only a slight surplus of applicants to seats in a class, it is imperative that admissions committees and officers have criteria other than grade point averages and PCAT scores to help assess the likelihood that a candidate who does not score as well as others in those objective measures of cognitive performance will make up for any deficiencies with outstanding non-cognitive performance. The reality is that not all our applicants will have top scores on the standardized tests and selecting among those who do not is a challenge for most admissions committees. Without measures of non-cognitive skills and attitudes, that selection comes to a matter of opinion of interviewers or admissions committees, which may well result in racial or ethnic bias.

Fortunately, there has been a great deal of work done by other health professions, especially dentistry and medicine, in establishing measures of non-cognitive skills and applying those to admissions decisions, resulting in more diverse classes. Holistic reviews that include evidence of both cognitive and non-cognitive skills and attitudes are becoming the norm in other health professional schools. We have work to do to catch up, but there is plenty of groundbreaking work preceding us.

We also need to focus on recruitment of applicants to the profession of pharmacy. Even if we adopt holistic admissions practices and expand the diversity of our classes, the pharmacy curriculum is rigorous and not all our applicants will be suitable for a career in pharmacy. We must increase our efforts to expand our applicant pools if we are to be able to apply holistic selection criteria and select those whose talents will both allow them to succeed in training and to positively influence the profession of pharmacy. Because it is key that applicants have appropriate pre-requisite knowledge and skills, especially critical thinking skills and a desire to care for people, we must begin recruiting and preparing applicants in their high school careers and follow them through the pre-pharmacy period. We must also better inform the many individuals who influence the career decisions of our potential applicants about the pharmacy profession in its contemporary patient care-focused form so their decisions are supported by parents, mentors, and advisors.

In the focus on recruitment to the pharmacy profession, we must be aware of the competition not just among colleges and schools of pharmacy, but competition from other health professions. According to the Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant (ARC-PA) the number of accredited PA programs has increased from 156 in 2011 to 196 in 2015.19 Additionally, the number of applicants to the physician assistant centralized application service, CASPA (which includes 177 programs), has increased from 16,569 in 2011 to 21,730 in 2014 (data obtained from Physician Assistant Education Association).

In the same time frame, osteopathic medicine programs have increased from 32 in 2011 to 37 in 2015 and their applicant pool has increased from 14,087 in 2011 to 17,944.20 As the role of the pharmacist increasingly includes more primary care activities and similar responsibilities to physicians and physician assistants, applicants will have more choices that will allow them to pursue a career in the health professions that allows them to provide primary care services. It is important that we educate potential applicants about the changing role of the pharmacist so applicants clearly see and understand the opportunities and rewards of a career in pharmacy.

The AACP Special Committee on Admissions has produced a set of recommendations for schools and colleges of pharmacy, AACP, and ACPE to consider. The recommendations for schools and colleges are aimed at administrators, faculty and admissions professionals and encompass recommendations both for recruitment and for admissions processes. We strongly support the holistic approach to admissions and sense the need for education of all those involved in the admissions process so they understand both the evidence and the necessary approaches that are needed to achieve our goals. We propose a number of ways that this goal of education can be achieved, including learning from the other health professions who have engaged in this issue.

The recommendations aimed at AACP provide an infrastructure to give this issue the attention we believe it deserves. It would create a full-time staff position within the organization, working with the student affairs team, focused on Recruitment and Diversity and leading the research and dissemination of information concerning holistic admissions, thus building the necessary expertise within our schools and colleges and helping to advance the field.

The committee also recommends a Bylaws change to create a standing committee for recruitment, admissions and student affairs. We feel that without such a committee, matters that are critical to our future will not receive the steady attention they deserve and are then left to periodic special committees.

Finally, the Committee has made recommendations aimed to ACPE. We recognize that standards have just recently been revised for 2016, but we believe there needs to be both additions to the standards, as well as additions to the rubrics used to assess the standards, to ensure that as an academic enterprise for the profession of pharmacy, we are making the adjustments necessary to ensure that we are serving all of society fairly and helping to reduce health disparities, as well as ensuring that we have selected the very best individuals as pharmacy professionals.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To address the goal of admitting students with the skills necessary to become the pharmacy leaders and innovators of the future, the Special Committee on Admissions developed the following recommendations for schools and colleges of pharmacy, AACP and ACPE.

As a cornerstone, it is recommended that holistic admission processes be adopted broadly across pharmacy education. Holistic admission provides a means for programs to evaluate applicants beyond the academic profile as required by ACPE, and supports the creation of a diverse learning environment and health workforce that is equipped to advance health equity. Holistic admissions practices support the ability of schools/colleges to evaluate applicants with the propensity to develop the characteristics outlined in ACPE Standard 4: the knowledge, skills, abilities, behaviors and attitudes necessary to demonstrate self-awareness, leadership, innovation and entrepreneurship, and professionalism.2

With this in mind, the Special Committee on Admissions offers the following recommendations to academic pharmacy stakeholders: Schools and Colleges of Pharmacy, AACP and ACPE.

Recommendations to Schools and Colleges of Pharmacy

Each school and college of pharmacy develops faculty-driven admissions practices which reflect the values, expectations and requirements specific to the institution. The Special Committee on Admissions encourages all schools and colleges of pharmacy to strengthen institution specific processes by incorporating admissions best practices aimed at identifying a diverse student body of future professional leaders. The AACP Special Committee on Admissions recommends schools and colleges of pharmacy:

• Utilize admissions processes that support the University/School/College mission.

• Include diversity in the college mission and/or values statement.

• Establish an admissions committee mission statement and goals to drive admissions practices.

• Ensure CEO deans and their delegates have a foundational understanding of and responsibility for implementation of admissions which includes knowledge of:

○ admission best practices;

○ PharmCAS participation requirements (if applicable);

○ implications of national admission trends;

○ assessment of applicant characteristics as predictors of success in the curriculum and achievement of program outcomes.

• Train all who participate in the admissions process in line with their role. Participants should be aware of and work to implement admissions best practices, including, but not limited to: holistic review; interviewing processes; evaluation criteria; and the connection between admissions processes and the mission of the school or college and the mission/goals for admissions.

• Review admissions criteria, scoring rubrics, and interview methodologies annually to improve admissions processes.

• Publish annually, amend publicly and adhere to documented application, acceptance and admissions procedures.

• Encourage collaboration between the curriculum and admissions committees to review pre-requisite requirements and assess how they impact the applicant pool.

• Participate in collaborative admissions practices developed to support applicant decision making similar to practices developed in other health professions (see Appendix C).

Recommendations to AACP

AACP is central to providing member schools/colleges with the information, tools and training needed to implement state of the art admissions practices used to identify the next generation of pharmacy leaders. AACP’s leadership in the areas outlined below is critical to achieving this goal.

Holistic admissions

To facilitate the implementation of holistic admissions across the academy, it is recommended AACP:

-

• Endorse Holistic admissions in AACP Policy & Bylaws.

AACP support of holistic admissions should be reflected in the Association’s Bylaws. The Special Committee submitted the following policy and AACP Bylaws change to the AACP House of Delegates for adoption at the July 2015 AACP House of Delegates:

“AACP supports the use of holistic review admissions processes for pharmacy education to provide a diverse learning environment and health workforce to advance health equity.”

-

• Develop a holistic review process for pharmacy

The development of a holistic review process specific to pharmacy, which includes best practices, and provides guidance for schools to incorporate a holistic approach to admissions is needed. In addition to assisting schools to select the characteristics for leadership and innovation in pharmacy practice, this process can highlight approaches to cultivate the student body essential to creating a diverse learning environment and serve the needs of society to positively impact health care equity.

-

• Implement an Admissions Institute

The creation of an Institute for admissions teams will provide for training in admissions best practices and an opportunity for focused development of admissions processes to meet college or school goals and identify students with the potential for professional leadership and innovation. Through the Institute, teams can learn about holistic review specific to pharmacy, interviewing processes (such as the Multiple Mini-Interview), admissions scoring, competency assessment in admissions for non-cognitive factors, legal issues in admissions, as well as the connection between admissions and curricular outcomes. Institute teams consisting of 3-5 school/college representatives should include the CEO dean and individuals in the following roles: Associate/Assistant Dean for Student Affairs/Admissions, Diversity officer, Director of Admissions, Admissions Committee Chair, Admissions Committee member, and/or Assessment officer.

-

• Provide on-going admissions training

To supplement training provided through the Institute, AACP should offer ongoing admissions training on the basics of holistic review, as well as personalized training for individual programs on a consultant basis. This training can be offered to faculty and staff involved in administering and implementing admissions.

-

• Collaborate with other health education associations in development of admissions resources and training

Other health education associations share the goal of developing holistic approaches to identifying students to be effective healthcare practitioners and leaders, and many have developed resources and training opportunities for their membership. AACP should develop partnerships and identify opportunities for collaboration in the development of resources and training opportunities related to holistic review

Recruitment

Successful admission of students with the potential to impact pharmacy practice begins with and is contingent upon a strong and diverse applicant pool. It is recommended AACP:

-

• Create a Director of Recruitment and Diversity position at AACP

To bring focus and leadership to efforts aimed at recruiting the best and brightest students to consider pharmacy, capitalize on opportunities for collaboration and expand service to the membership, AACP should create a new professional staff position with expertise in recruitment and a strong understanding of pre-health professional advisement to spearhead pharmacy recruitment at a national level. This position will bring focus and attention to strategic initiatives and programs to reach and encourage underrepresented students to consider pharmacy. This individual would work with the Senior Director of Strategic Academic Partnerships to expand on the current applicant recruitment activities of AACP and build awareness among prospective students and health professions advisors by promoting the profession of pharmacy, career opportunities, the requirements of a pharmacy education, etc. This individual will:- ○ Identify barriers to admission to pharmacy school for under-represented students, as well as solutions to help applicants overcome these barriers.

- ○ Serve as a resource to the health professions advisors association and attend national and regional meetings (NAAHP, HOSA, NACADA, NASPA, ASCA, etc.). The Director of Recruitment and Diversity will design and deliver workshops, serve as an exhibitor and resource, participate in key events (e.g. Meet the Deans), and coordinate submission of admissions and pre-pharmacy related articles to relevant publications (AJPE, The Advisor, etc.).

- ○ Develop and maintain a recruitment toolkit with the assistance of members from the appropriate committees/Special Interest Groups.

- ○ Work with the AACP communications team to ensure website and social media appeal to all target audiences.

- ○ Enhance the AACP website content with specific sections for advisors, prospective students and schools of pharmacy.

- ○ Work with other pharmacy organizations to promote the profession of pharmacy through facilitation of the Pharmacy Career Information Council (PCIC), a subcommittee of the Pharmacy Workforce Center, Inc., whose mission is to assist prospective and current student pharmacists in accessing accurate information regarding the profession of pharmacy and pharmacist career pathways.

-

• Create a network of schools to advance recruitment at the state, regional and national level

AACP should develop a memorandum of understanding to develop a network of schools that would collaborate in recruitment activities within their state/region and support AACP efforts at a national level.- ○ Assist the AACP staff at local, state, regional and national meetings by exhibiting, delivering workshops, interacting, educating and networking with health professions advisors.

- ○ Create a repository of representatives from participating schools who are willing to assist.

- ○ Establish collaborative strategies designed to expand the pipeline of diverse, fully - prepared and qualified candidates for schools through the early identification, cultivation and mentoring of students in high schools, community colleges, four year institutions and professional schools.

- ○ Promote administrative and programmatic mechanisms to build collaborations and partnerships, expand relationships, and share intellectual talent and technical expertise between and among the member institutions.

Research and publication

Continued development of admissions best practices must be grounded in research and scholarship. To that end, AACP can support the development of research and evidence-based admissions practices on several fronts:

-

• Include admissions perspective on the AACP Institutional Research and Assessment Committee

The addition of an individual with expertise in admissions to this committee will help ensure the application, enrollments and degrees conferred reports are accurate and informative.

-

• Initiate admissions-related research

Research on admissions topics should be encouraged and performed by AACP. Many of these topics also represent prime opportunities to collaborate with other health education associations. Examples include:- ○ measurement of non-cognitive curriculum competencies as they relate to non-cognitive admissions competencies;

- ○ investigation of appropriate cognitive and non-cognitive pre-requisite competencies for success (academic and professional) in pharmacy school and in the profession;

- ○ identification of valid and reliable measurement tools of non-cognitive skills;

- ○ analysis of admissions staffing within schools and colleges of pharmacy; and

- ○ development of tools to assess dimensions of diversity.

-

• Publish an Admissions Theme-Based Issue of AJPE

The Special Committee recommends AJPE develop and publish an admissions theme-based issue on a yearly or bi-yearly basis.

Standing committee for recruitment, admissions and student affairs

The ongoing advancement and oversight of these initiatives as well as identification and response to emerging issues must involve representation from experts within the association’s membership. The Special Committee on Admissions recommends AACP:

-

• Create a standing Committee for Recruitment, Admissions and Student Affairs

Amending the Association Bylaws to include a standing committee for recruitment and admissions will establish a mechanism to guide the Association and schools and colleges of pharmacy on admissions and recruitment related policies and practices. In addition, this committee can guide the research agenda related to admissions and recruitment.

Proposed AACP Bylaws Change

WHEREAS AACP bylaws dictate a standing committee on academic affairs, advocacy, the future of pharmacy education (Argus Commission), professional affairs and research and graduate affairs;

WHEREAS student affairs, including admissions and recruitment activities, are an important component of pharmacy education and are vital to the success of schools and colleges of pharmacy:

The AACP Special Committee on Admissions recommends that the Association Bylaws be amended to include a standing committee for recruitment, admissions, and student affairs to guide the Association and schools and colleges of pharmacy on admissions, recruitment and student affairs related policies and practices. This committee will guide the Association’s research agenda related to admissions and recruitment.

Admissions tools

AACP supports member schools and colleges by providing resources to meet emerging needs. Admissions committees and faculty across the association seek tools to assess the behavioral attributes of applicants and to evaluate their potential as healthcare providers. The Special Committee supports AACP efforts to:

-

• Develop a Situational Judgment Test

The PCAT Advisory Committee has recommended AACP develop a situational judgment test for use as an additional admissions tool. The Special Committee on Admissions supports the development of this tool.

Recommendations to the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education

ACPE standards provide admissions guidance for Schools and Colleges of Pharmacy by establishing standards to support the high quality education and successful graduation of PharmD students. The Special Committee on Admissions looks to ACPE to support admissions best practices and offers the following recommendations:

Reference diversity in accreditation standards related to admission and vision/mission/goals

The Special Committee on Admissions was active during the review period for ACPE Standards 2016 and put forth the following suggestions for inclusion in the standards:

Standard 16: Admissions

Recommended reference to diverse student body (word highlighted for reference only) in description of standard:

The college or school must develop, implement, and assess its admission criteria, policies, and procedures to ensure the selection of a qualified and diverse student body into the professional degree program.

Recommendation was adopted.

Recommended additional key element in Standard 16:

Diversity – Schools or colleges must demonstrate efforts to enhance the diversity of their applicant pool.

This recommendation was based on the Sullivan Commission and the 2004 Institute of Medicine report on ensuring diversity in the healthcare workforce.21, 22

While not included in ACPE Standards 2016, recommend re-submission when standards are revised in the future.

Standard 6: College or School Vision, Mission and Goals

Recommended additional key element in Standard 6:

Diversity – The mission or vision for the school or college should include a statement reflecting the value of diversity and inclusivity.

Recommendation based on the 2014 Argus report23; while not included in ACPE Standards 2016, recommend re-submission when standards are revised in the future. Schools and colleges of pharmacy need to be aware that if they meet the change in Standard 16 related to diversity, that it must be supported by their mission to avoid potential legal action.

Support collaborative admissions practices developed to support applicant decision making

Schools and colleges of pharmacy are dependent upon one another and cooperation among members of the Academy in the area of admissions benefits applicants and supports the admissions processes of schools and colleges of pharmacy. ACPE Standards 2016, Standard 9.3 Organizational Culture – Culture of Collaboration states:

“The college or school develops and fosters a culture of collaboration within subunits of the college or school, as well as within and outside the university, to advance its vision, mission, and goals, and to support the profession.”2

The Special Committee on Admissions recommends that collaborative admissions practices be reviewed by ACPE as part of this standard and that future guidance documents reflect the importance of collaborative practices among and between schools and colleges with respect to admissions decisions.

Include admissions/student affairs experts on every site team

Strong, well-developed admissions processes consistent with identified best practices are central to a school or college’s ability to identify and enroll students who can successfully complete rigorous pharmacy training and advance the profession through leadership and innovation. In order to assess the quality of the admissions process and advance the use of best practices in admissions, the Special Committee recommends every site team include at least one member with expertise in admissions and student affairs.

CONCLUSION

The Special Committee on Admissions has studied the twin issues of recruitment and admissions from a number of perspectives and has developed a series of recommendations which will require significant commitment on the part of admissions professionals, admissions committees, as well as ACPE and AACP. We believe these recommendations are critical to the advancement of pharmacy education and represent important opportunities to respond to the challenge posed at the Committee’s inception: Are We Producing Innovators and Leaders, or Change Resisters and Followers? Action is needed now to achieve the goals of admitting a diverse student body with the motivation, attitudes and critical thinking skills to lead our profession into the future.

Appendix A. Summary of Pharmacy Admissions Research

Current pharmacy literature has examined academic performance and success at single institutions and has focused generally on cognitive skills and more objective measures. The literature has explored the association between advanced chemistry, biology, and math coursework (junior and senior level college classes beyond required prerequisites) as well as the attainment of a prior college degree (BS, BA, or MS)1 and academic success. Additional research has examined preadmission factors and their ability to predict success on the North American Pharmacist Licensure Examination (NAPLEX) test.2 The limited amount of this type of research supports the notion that evidence to support admissions practices is needed.

Current pharmacy literature has examined academic performance and success at single institutions and has focused generally on cognitive skills and more objective measures. The literature has explored the association between advanced chemistry, biology, and math coursework (junior and senior level college classes beyond required prerequisites) as well as the attainment of a prior college degree1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. This research is conducted at single institutions but does not investigate whether the same results would be true at a small group of institutions or at a random sampling of institutions. Academic performance or success has consistently been defined as early classroom grade point average (GPA for first 3 years of professional degree education).1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10

Some non-cognitive factors including communication skills, critical thinking scores and interview scores have been examined.7, 11 Mar et al. examined previous pharmacy work experience and the impact on academic success, which provides a framework for a national evaluation of healthcare related extracurricular experience and academic success.12 Clinical success generally has been measured by experiential performance, namely grades in introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs) or advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs). Other measures of pharmacy student clinical performance that tend to be more subjective in nature have included low-stakes progress examinations, high-stakes progress examinations, and case-based objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) which have generally been less accurate in predicting students’ clinical success7, 11, 13

Cognitive versus non-cognitive skills

College admission practices rely heavily on predictive measures of success. Many schools utilize objective measures of prediction, commonly referred to as “cognitive measures” such as previous degree, GPA, and standardized testing. However, there are also “non-cognitive traits” including maturity, motivation, determination, etc. which can influence success. Controversy exists regarding the composition of non-cognitive traits which impact the overall ability of an individual to succeed.14, 15, 16, 17

Research has established grade point average (GPA), standardized tests, and past academic performance as the most valid predictors for graduate school success. Therefore, acceptance criteria for many health professions have relied solely on GPA and standardized testing as they are also predictive of success on licensing exams.18 However, these measures may not be the only predictors19. Carl Rogers rejected objective measures as predictive for college success as they support conformity as opposed to the freedom of mind coming with academic scholarship20. Cortes illuminated a common discussion held among educators and admissions officers, who have regularly observed non-cognitive student attributes that have accounted for student success21.

“Students who stand out are those who work harder; are intrinsically motivated or curious; or persevere through challenges within the individual family setting or in the context of larger structural settings or poorly-resourced schools and communities kept to the margin by race, language, or economic barriers”.21

Cortes suggested a profile-oriented approach to admission as it recognizes and takes into account the impact of sociological factors over time and seeks to understand how students manage and rise above barriers21.

Holistic review for graduate and professional admissions

Researchers of graduate populations have also investigated the predictive validity of measures typically used by admissions officers. Hagedorn and Nora discussed alternative criteria better reflecting the skills and abilities predictive of success for graduate study. They proposed that traditional admissions measures do not necessarily provide evidence of success regarding the type of learning to be expected of doctoral students and, therefore, are unable to predict the ability to learn what is required.22 Johnson identified many traits that professional graduate programs have deemed highly important in their admissions process, including resourcefulness, persistence in the face of obstacles, unusual personal experiences, independent accomplishments, academic and nonacademic interests, career goals, and recommendations by others who know the applicant well.23

Non-cognitive measures as predictor for professional skills

The validity of cognitive measures in the admissions process as related to success has been questioned in the literature not only relative to academic pursuits, but also as a predictive measure of professional skills. Nelson et al.’s review of the literature revealed that historically, academic criteria such as GPAs and standardized testing are more predictive of academic achievement rather than professional skills required of individuals in the health or helping professions16. Kreiter and Kreiter summarized and interpreted the literature on validity of the use of MCAT and GPA for selection to medical schools using validity generalization techniques accounting for measurement error. The researchers identified conflicting interpretations and debate regarding whether these two measures can predict clinical performance.24 Finally, Helm posited utilization of cognitive measures alone can present a barrier for diverse students and proposed increased research in the area of non-cognitive assessment and the use of surveys about life performance and characteristics found to be desirable in health professions.18

Alternatively, O’Neill et al. discussed the controversial nature of utilizing non-cognitive criteria in medical admissions. They posited medical and other schools overwhelmingly use non-cognitive factors in the admissions process, yet very little research has substantiated the reliability and validity of non-cognitive traits to support their inclusion in admissions decisions.25 Unfortunately, non-cognitive traits such as determination to succeed, ambition, maturity, and intellectual curiosity are not easily measured. To date, the consensus of many programs suggest non-cognitive measures are important to a successful admissions process, but most of the studies suggested non-cognitive traits are not measurable.16

Holistic review and access to education

Often, students with marginal scores on the objective measures are not only able to succeed by the compensation of non-cognitive traits, but tend to be more desirable students and stronger contributors to their professions and the community.26, 27 It is possible many strong students are denied admission because they lack the objective measures that historically predict success and colleges may overlook students who would not only be successful academically, but also become strong contributors in their profession.28 Many college admissions administrators and faculty express a desire to effectively measure the non-cognitive traits of a candidate because students with strong non-cognitive skills tend to be more engaged in the learning process, motivated to succeed, committed to lifelong learning, and appreciate the effort required to be successful.17, 21, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 Furthermore, as Hamilton and Freeman stated quite some time ago, “As the demand for higher education increases, questions are bound to be asked that have profound bearing on the usefulness of the methods of selection, on educational ideals and aims, and whether the results justify the money and effort invested”.34

Finally, a study conducted by Adebayo revealed, while traditional cognitive measures were a valid predictor of success for fully admitted students, conditionally admitted students tend to have better predictors of success with a combination of both cognitive and non-cognitive measures. Other skills such as leadership, community service, self-concept, and self-appraisal have been strong predictors of success for marginal students.21, 26, 32, 35 This literature review has mostly highlighted research in undergraduate populations related to cognitive vs. non-cognitive predictors for success in admissions practices because research on this topic has been given limited attention, if at all, in the pharmacy education research.

A recent article by Cortes summarized the dilemma of weighting cognitive vs. non-cognitive factors in admissions decisions. She highlighted the differential validity of utilizing cognitive measures for specific groups of students (women, men, Blacks, Hispanic, low socio-economic status, etc.), and clarified that cultural bias is not necessarily at play, but rather the meaning of the results for cognitive assessments are not the same for all groups of students. Essentially, one size does not fit all. Therefore, when scores from cognitive measures are utilized as cut-offs for admission, “small differences in scores can translate into meaningful differences in access for women, students of color, or low-income students. Test-oriented admission practices, therefore, only increase the obstacles to access without improving an institution’s capacity to predict student success”.21

Appendix A references

- 1.McCall KL, Allen DD, Fike DS. Predictors of academic success in a doctor of pharmacy program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006 doi: 10.5688/aj7005106. 70(5):Article 106, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCall KL, MacLaughlin EJ, Fike DS, Ruiz B. Preadmission predictors of PharmD graduates’ performance on the NAPLEX. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007 doi: 10.5688/aj710105. 71(1):Article 5, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chisholm MA, Cobb HH, Kotzan JA. Significant factors for predicting academic success of first-year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 1995;59(4):364–370. doi:aj5904364.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chisholm MA, Cobb HH, Kotzan JA. Prior four year college degree and academic performance of first-year pharmacy students: a three-year study. Am J Pharm Educ. 1997;61(3):278–281. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisholm MA, Cobb HH, DiPiro JT. Development and validation of a model that predicts the academic ranking of first-year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 1999;63(4):388–94. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houglum JE, Aparasu RR, Delfinis TM. Predictors of academic success and failure in a pharmacy professional program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005 69(3):Article 43, 283–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen DD, Bond CA. Pre-pharmacy indicators of success in pharmacy school: grade point averages, pharmacy college admission test, communication abilities, and critical thinking skills. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:842–9. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.9.842.34566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardigan PC, Lai LL, Arneson D. Robeso, A. Significance of academic merit, test scores, interviews and the admissions process: a case study. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65(1):40–44. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley KA, Secnik K, Boye ME. An evaluation of the Pharmacy College Admissions Test as a tool for the pharmacy college admissions committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65(3):225–230. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas MC, Draugalis J. Utility of the pharmacy college admission test (PCAT): implications for admissions committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66(1):47–51. doi:aj660107.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill LH, Delafuente JC, Sicat BL, Kirkwood CK. Development of a competency-based assessment process for advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(1):Article 1. doi: 10.5688/aj700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mar E, Barnett MJ. Tang TT-L, Sasaki-Hill D, Kuperberg J R, Knapp K. Impact of previous pharmacy work experience on pharmacy school academic performance. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010 doi: 10.5688/aj740342. 74(3):Article 42, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kidd RS, Latif DA. Traditional and novel predictors of classroom and clerkship success of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(4):109. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Nasir FAL, Robertson AS. Education for Health: Change in Learning & Practice. 2. Vol. 14. a study at Arabian Gulf University; 2001. Can selection assessments predict students’ achievements in the premedical year? pp. 277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kulatunga Moruzi C, Norman GR. Validity of admissions measures in predicting performance outcomes: the contribution of cognitive and noncognitive dimensions. Teaching & Learning in Medicine. 2002;14(1):34–42. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1401_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson KW, Canada RM, Lancaster LB. An investigation of nonacademic admission criteria for doctoral-level counselor education and similarprofessional programs. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education & Development. 2003;42(1):3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziv A, Rubin O, Moshinsky A, Gafni N, Kotler M, Dagan Y, Mittelman M. MOR. a simulation-based assessment centre for evaluating the personal and interpersonal qualities of medical school candidates. Medical Education. 2008;42(10):991–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helm DM. Standardized test scores as acceptance criteria for dental hygiene programs. Journal of Allied Health. 2008;37(3):169–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shivpuri S, Schmitt N, Oswald FL, Kim B. Individual differences in academic growth: do they exist and can we predict them? Journal of College Student Development. 2006;47(1):69–87. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers C. Freedom to Learn. Columbus, OH: Merrill, 1969. Rogers C. A revolutionary program for graduate education. Library College Journal. 1970;3(2):16–26.

- 21.Cortes CM. Profile in action: linking admission and retention. New Directions for Higher Education. 2013;161:59–69. doi: 10.1002/he.20046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagedorn LS, Nora A. Rethinking admissions criteria in graduate and professional programs. New Directions for Institutional Research. 1996;(92):31. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson JL. Admissibility of students to PhD programs in counseling psychology. Dissertation Abstracts International. 1996;57(9):3843. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreiter CD, Kreiter Y. A validity generalization perspective on the ability of undergraduate GPA and the Medical College Admission Test to predict important outcomes. Teaching & Learning in Medicine. 2007;19(2):95–100. doi: 10.1080/10401330701332094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Neill LD, Korsholm L, Wallstedt B, Eika B, Hartvigsen J. Generalisability of a composite student selection programme. Medical Education. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03247.x. 2009;43(1):58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adebayo B. Cognitive and non-cognitive factors. Journal of College Admission. 2008;200:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brannick MT, Wahi MM, Arce M, Johnson H-A, Nazian S, Goldin SB. Comparison of trait and ability measures of emotional intelligence in medical students. Medical Education. 2009;43(11):1062–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulatunga Moruzi C, Norman GR. Validity of admissions measures in predicting performance outcomes: The contribution of cognitive and noncognitive dimensions. Teaching & Learning in Medicine. 2002 doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1401_9. 2002;14(1):34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bore M, Munro D, Powis D. A comprehensive model for the selection of medical students. Medical Teacher. 2009;31(12):1066–1072. doi: 10.3109/01421590903095510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hulsman RL, van der Ende JSJ, Oort FJ, Michels RPJ, Casteelen G, Griffioen FMM. Effectiveness of selection in medical school admissions: evaluation of the outcomes among freshmen. Medical Education. 2007;41(4):369–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2007.02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noonan B, Sedlacek W, Veerasamy S. Employing noncognitive variables in admitting and advising community college students. Community College Journal of Research & Practice. 2005;29(6):463–469. doi: 10.1080/10668920590934170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ting SR. Predicting first-year grades and academic progress of college students of first-generation and low-income families. Journal of College Admission. 1998;158:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urlings-Strop LC, Stijnen T, Themmen APN, Splinter TAW. Selection of medical students: a controlled experiment. Medical Education. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03267.x. 2009;43(2): 175–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamilton V, Freemant P. 1. Academic achievement and student personality characteristics: a multivariate study. British Journal of Sociology. 1971;22(1):3.

- 35.Tracey TJ, Sedlacek WE. Noncognitive variables in predicting academic success by race. Measurement & Evaluation in Guidance. 1984;16(4):171–178. [Google Scholar]

Appendix B. Noncognitive Assessment Tools

• Tracey and Sedlacek developed the Non-Cognitive Questionnaire (NCQ) (1984), which has been applied to several student populations. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

• Several colleges of medicine have developed tools to measure non-cognitive skills in the selection process.6, 7, 8, 9 For example, Ziv et al. developed the Selection for Medicine (MOR) for admissions selection to measure non-cognitive skills, including an interview in which interpersonal communication, ability to handle stress, initiative and responsibility, and self-awareness are considered. The MOR was derived from the Multiple-Mini Interview (MMI) developed at McMaster University.9

• Bore, Munro, and Powis’ research (2009) also developed a model for selection of medical school students including measures for both cognitive and non-cognitive traits supporting the notion that non-cognitive traits are important in the admissions process. The model included student self-selection through provision of timely vocational guidance, a cognitive measure of academic achievement, cognitive ability measured by psychometric testing, personality measured by psychometric testing, and interpersonal skills measured by an on-site interview. The personality measurement is based on an assessment of the Five Factor Model, measuring the Big Five personality traits to include extroversion, emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and open minded-ness.6

• Hulsman, van der Ende, Ort, Michels, Casteelen, and Giffioen (2007) also developed a new model for selecting Dutch medical school students for admission incorporating non-cognitive measures utilizing a standardized procedure. The selection procedure (SP) included measuring social and ethical understanding of health care, medical comprehension and interpersonal communication through a three step process.7 Applicants first wrote an essay and top applicants were then invited for one day of medical education. Then, applicants were required to take assessments to include an examination on the material presented during the day of medical education. Finally, the participants completed a computer objective structured video examination on social skills. Students were administered a questionnaire on motivation (), study behavior and extra-curricular activities.10 The Strength of Motivation for Medical School instrument (SMMS) derived from Vermunt’s motivation scale of the Inventory Learning Style was utilized to measure motivation.7

• Three publications utilizing the SMMS were identified.11, 12, 13

• Another study developed a new selection procedure for medical school applicants in the Netherlands.8 The researchers hypothesized that students with stronger extra-curricular activities, motivation, and ambition to achieve compared to their peers will not only perform better in medical school but afterwards in the profession as well. The S-Group process for admission included analysis of extra-curricular activities and assessment of five cognitive tests on a medical subject, which included questions on logical reasoning, scientific thinking, epidemiology and pathology, anatomy, and philosophy.8

• Random selection is considered a fair way for some colleges to determine which candidates to admit, when all other qualifications are equal.14

• Clearly, schools are attempting to improve ways in which to measure non-cognitive skills as a potential predictor for academic success in an effort to inform admissions decisions. Researchers have attempted to measure the reliability and validity of non-cognitive skills through the use of quantifiable measures such as validated scoring tools, rating scales, and rubrics.15 Considering the majority of schools are weighting non-cognitive factors as equal to cognitive factors in acceptance standards, it is important to begin measuring the non-cognitive factors objectively.15 While the admissions process has traditionally utilized a personal statement, letters of recommendation, and the interview to identify non-cognitive traits, themes seem to be emerging in the literature including the use of videotapes, role plays, onsite writing samples, interpersonal skills assessment, and evidence of professional interest or leadership.15

Appendix B references

- 1.Fuertes JN, Sedlacek WE. Using the SAT and noncognitive variables to predict the grades and retention of Asian American. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development. 1994 1994;27(2):74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noonan B, Sedlacek W, Veerasamy S. Employing noncognitive variables in admitting and advising community college students. Community College Journal of Research & Practice. 2005;29(6):463–469. doi: 10.1080/10668920590934170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ting SR. A longitudinal study of non-cognitive variables in predicting academic success of first-generation college students. College and University. 2003;78(4):27–31. 249. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ting SR. Impact of noncognitive factors on first-year academic performance and persistence of NCAA Division I student athletes. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education & Development. 2009 2009;48(2):215–228. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tracey TJ, Sedlacek WE. Factor structure of the non-cognitive questionnaire – revised across samples of black and white college students. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1989;49(3):637–648. doi: 10.1177/001316448904900316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bore M, Munro D, Powis D. A comprehensive model for the selection of medical students. Medical Teacher. 2009 doi: 10.3109/01421590903095510. 2009;31(12):1066–1072. doi: 10.3109/01421590903095510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hulsman RL, van der Ende JSJ, Oor FJ, Michels RPJ, Casteelen G, Griffioen FMM. Effectiveness of selection in medical school admissions: evaluation of the outcomes among freshmen. Medical Education. 2007;41(4):369–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2007.02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urlings-Strop LC, Stijnen T, Themmen APN, Splinter TAW. Selection of medical students: a controlled experiment. Medical Education. 2009;43(2):175–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziv A, Rubin O, Moshinsky A, et al. MOR: a simulation-based assessment centre for evaluating the personal and interpersonal qualities of medical school candidates. Medical Education. 2008;42(10):991–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nieuwhof M, ten Cate O, Oosterveld M, Soethout M. Measuring strength of motivation for medical school. Med Educ Online. 2004 doi: 10.3402/meo.v9i.4355. 2004;9(16):7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kusurkar R, Croiset G, Kruitwagen C, ten Cate O. Validity evidence for the measurement of the strength of motivation for medical school. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2011;16(2):183–195. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusurkar R, Kruitwagen C, ten Cate O, Croiset G. Effects of age, gender, and educational background on strength of motivation for medical school. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2010;15(3):303–313. doi: 10.1007/s10459-009-9198-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luqman M. Relationship of academic success of medical students with motivation and pre-admission grades. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan. 2013;23(1):31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone P. Access to higher education by the luck of the draw. Comparative Education Review. 2013;57(3):577–599. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson KW, Canada RM, Lancaster LB. An investigation of nonacademic admission criteria for doctoral-level counselor education and similar professional programs. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education & Development. 2003;42(1):3–13. [Google Scholar]

Appendix C. Other Health Professions Cooperative Admissions Guidelines

This appendix provides an overview of the cooperative admissions guidelines developed by health profession education associations. The guidelines proposed by the Special Committee for ACCP are included as a final section of the appendix.

American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM)

AACOM encourages each of its member colleges to conduct an application process that is inclusive and professional. The purpose of these guidelines is to allow prospective students to explore their options with the osteopathic medical community and to give the colleges of osteopathic medicine the ability to process, select and matriculate applicants in a fair and timely manner.

1. Colleges of osteopathic medicine will publish and follow an application schedule.

2. Colleges of osteopathic medicine will publish their respective application procedures and admission requirements.

- 3. Colleges of osteopathic medicine may begin extending offers of admission at any time after the interview. Applicants will be asked to submit necessary matriculation documents, including a deposit, according to the following AACOMAS traffic guideline schedule:

- • Those accepted prior to November 15 will have until December 14. Those accepted between November 15 and January 14 will have 30 days.

- • Those accepted between January 15 and May 14 will have 14 days.

- • Those accepted after May 15 may be asked for an immediate deposit.

- • After May 15 of the year of matriculation, each medical college may implement college-specific procedures for accepted students who hold one or more seats at other medical colleges.

Starting April 1, osteopathic medical colleges report to AACOMAS the names and identification of candidates who have paid a deposit, hold a position at an osteopathic medical college entering class or both. After May 15, AACOMAS reports to each institution the names and candidates for its entering class who hold an acceptance(s) at additional institutions. An osteopathic medical college may rescind an offer of admissions to a candidate who has paid deposits to or holds positions at multiple institutions. If the osteopathic medical college chooses to withdraw the candidate from the entering class, the college must give the candidate a minimum 15-day notice.

After the 15-day notice, if the candidate does not respond and is withdrawn from a college, the deposit is forfeited and the seat may be given to another candidate. Therefore, prior to May 15, applicants need to withdraw from any college(s) which they do not plan to attend and only hold a position at one college of osteopathic medicine to avoid having positions withdrawn. Prospective osteopathic medical students are expected to provide factual, accurate and complete information throughout the admissions process. AACOM believes that the process requires mutual respect, integrity and honesty among the colleges of osteopathic medicine and between colleges and their prospective osteopathic medical students (COMS). Osteopathic Medical College Information Handbook http://www.aacom.org/news-and-events/publications/cib

American Dental Education Association (ADEA)

Earliest notification date

Dental schools begin notifying applicants, either orally or in writing, of provisional or final acceptance no earlier than December 1 of the academic year prior to the academic year of matriculation. For example, offers of acceptance for fall 2012 begin no earlier than December 1, 2011.

Applicant response periods

Applicants extended an offer of acceptance between December 1 and January 31 have 30 days to respond. The response period for applicants extended an offer of acceptance on or after February 1 and through May 15 is 15 days. Applicants accepted after May 15 may be asked for an immediate response to an admissions offer.

Applicants holding positions at multiple institutions

Starting April 1, dental schools report to ADEA AADSAS the names and identification numbers of candidates who have paid a deposit, hold a position in a dental school entering class, or both. After April 5, ADEA AADSAS reports to each institution the names of candidates for its entering class who hold acceptance(s) at additional institutions.

A dental school may rescind an offer of admission to a candidate who has paid deposits to or holds positions at multiple institutions. If the dental school chooses to withdraw this candidate from the entering class, the dental school must give the candidate a minimum 15-day notice. These are highlights from the ADEA Guidelines for Dental Schools When Extending Offers of Admission, approved March 2010 by the ADEA House of Delegates. To see the complete guidelines, go to: http://www.adea.org/dental_education_pathways/AFASA/GoADEA_AFASA/Documents/2010%20ADEA%20Guidelines%20for%20Dental%20Schools%20When%20Extending%20Offers%20of%20Admission.pdf

Association of American Law Schools (AALS) Law School Admissions Council (LSAC)

Admission policies are the written description(s) of the general approach a law school takes in admissions and the specific instructions available to prospective applicants and admitted students. Member law schools should: develop concise, coherent, written admission policies that describe the factors (e.g., academic record, LSAT score, letters of recommendation, written statements, interviews) that may affect a decision; state clearly the admission policies, processes, and deadlines to all applicants and apply them consistently to all applicants; include in their admission policies procedures for reporting suspected instances of misconduct or an irregularity to LSAC’s Misconduct and Irregularities in the Admission Process Subcommittee; and review their admission policies periodically.

Commitments. A commitment is defined as an affirmative step taken by an applicant (e.g., submitting a seat deposit or an enrollment form) to indicate their intention to matriculate at an institution. Member law schools should: state clearly the policies and processes for submitting a commitment and holding a commitment and, if applicable, their policies regarding admitted students who may violate a commitment agreement, including any possible consequences that may result from holding multiple commitments simultaneously; request commitments of any kind only from admitted applicants no earlier than April 1, except under binding early decision plans or for academic terms beginning in the spring or summer; allow applicants to freely accept a new offer from a law school even though a scholarship has been accepted, a deposit has been paid, or a commitment has been made to another school; provide financial aid awards to admitted students who have submitted a timely financial aid application, before requesting any commitment; and report and update a student’s commitment accurately and in a timely manner. http://www.lsac.org/docs/default-source/publications-(lsac-resources)/statementofgoodadm.pdf?sfvrsn=4

Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC)

The AAMC recommends the following guidelines to ensure that M.D. and M.D.-Ph.D. applicants are afforded timely notification of the outcome of their applications and timely access to available first-year positions and that schools and programs are protected from having unfilled positions in their entering classes. These protocols are often referred to as “Traffic Rules” by admissions officers and pre-health advisors. These recommendations are distributed for the information of prospective M.D. and M.D.-Ph.D. students, their advisors, and personnel at the medical schools and programs to which they have applied.

The AAMC recommends that each M.D. or M.D.-Ph.D. granting school or program:

- 1. Comply with established procedures to:

- a. Annually publish, amend and adhere to its application, acceptance and admission procedures.

- b. Abide by all conditions of participation agreements with application services (if using).

- 2. Promptly communicate admissions decisions:

- a. By October 1, notify Early Decision applicants and the American Medical College Application Service (AMCAS) of Early Decision Program (EDP) admission actions.

- b. From October 15 to March 15, notify AMCAS within 5 business days of all admission actions, either written or verbal, that have been communicated to an applicant.

- c. From March 16 to the first day of class, notify AMCAS within 2 business days of all admissions acceptance, withdrawal, or deferral actions, either written or verbal, that have been communicated to an applicant. All admission actions are listed and defined on the AAMC website.

- d. An acceptance offer is defined as the point at which a medical school communicates a written or verbal acceptance offer to an applicant.

- e. An acceptance offer to any dual degree program that occurs after an initial acceptance should follow the above timelines.

3. Notify all Regular M.D. program applicants of their acceptance on or after October 15* of each admission cycle, but no earlier. Schools and programs may notify applicants of admissions decisions other than acceptance prior to October 15.

4. By March 15 of the matriculation year, issue a number of acceptance offers at least equal to the expected number of students in its first-year entering class and report those acceptance actions to AMCAS.

- 5. On or before April 30, permit ALL applicants (except for EDP applicants):

- a. A minimum of two-weeks to respond to their acceptance offer.

- b. To hold acceptance offers or a waitlist position from any other schools or programs without penalty (i.e. Scholarships).

- 6. After April 30, implement school-specific procedures for accepted applicants who, without adequate explanation, continue to hold one or more places at other schools or programs.

- a. Each school or program should permit applicants:

- 1. A minimum of 5 business days to respond to an acceptance offer. This may be reduced to a minimum of 2 business days within 30 days of the start of orientation.

- 2. Submit a statement of intent, a deposit, or both.

- b. Recognize the challenges of applicants with multiple acceptance offers, applicants who have not yet received an acceptance offer, and applicants who have not yet been informed about financial aid opportunities at schools to which they have been accepted.

- c. Permit applicants who have been accepted or who have been granted a deferral, to remain on other schools' or programs' wait lists. Also, permit these applicants to withdraw if they later receive an acceptance offer from a preferred school or program.

7. Each school's pre-enrollment deposit should not exceed $100 and (except for EDP applicants,) be refundable until April 30. If the applicant enrolls at the school, the school should credit the deposit toward tuition. Schools should not require additional deposits or matriculation fees prior to matriculation.

8. On or after May 15, any school that plans to make an acceptance offer to an applicant who has already been accepted to, or granted a deferral by, another school or program, must ensure that the other school or program is advised of this offer at the time it is issued (written or verbal) to the applicant. This notification should be made immediately by telephone and email by the close of business on the same day. The communication should contain the applicants name and AAMC ID number, the program being offered (ex. MD only, joint program), and the date through which the offer is valid. Schools and programs should communicate fully with each other with respect to anticipated late roster changes in order to minimize inter-school miscommunication and misunderstanding, as well as to prevent unintended vacant positions in a school's first-year entering class.

9. No school or program should make an acceptance offer, either verbal or written, to any individual who has officially matriculated/enrolled in, or begun an orientation program immediately prior to enrollment at an LCME accredited medical school. Medical programs should enter a matriculation action for students in AMCAS immediately upon the start of enrollment or the orientation immediately preceding enrollment.

10. Each school should treat all letters of evaluation submitted in support of an application as confidential, except in those states with applicable laws to the contrary. The contents of a letter of evaluation should not be revealed to an applicant at any time.*If any date falls on a weekend/holiday the recommendation(s) will apply to the following business day. Approved: AAMC Council of Deans Administrative Board, September 2014 AAMC link https://www.aamc.org/download/364264/data/2014trafficrules.pdf

Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry (ASCO)