A quarter of all prescriptions in palliative medicine are for licensed drugs that are used for unlicensed indications or that are given by an unlicensed route. Such prescriptions may affect two thirds of inpatients in specialist palliative care units.1,2 Doctors have been recommended to record in the patient's notes the reason for prescribing outside the licence; to explain, where possible, the position to the patient (and carers, if appropriate) in sufficient detail to allow informed consent to be given; and to inform other professionals involved in the care of the patient of such prescribing, so that misunderstandings are avoided.3 Given the widespread use of drugs outside their licence in palliative care, strict adherence to these recommendations may be impractical. In view of the implications of these recommendations for doctors in palliative medicine and other doctors they advise, a position statement endorsed by the specialty would be helpful. We undertook a survey of current practice to inform the debate.

Participants, methods, and results

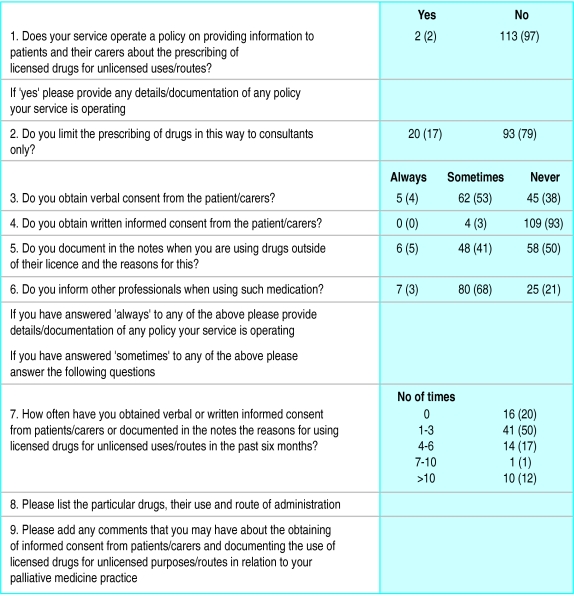

All 182 palliative care services in the United Kingdom with a medical director or consultant were asked to complete anonymously a postal questionnaire in October 1999 (figure). Informed consent was defined thus: “Patients have been given the information they asked for or need about their treatment in a way they can understand so that whenever possible the patients have understood the nature, purpose and material risks of what is proposed and consent to it before you provide treatment.”

One hundred and seventeen questionnaires (64%) were returned. When unlicensed prescribing was limited to consultants, this was generally in the context of a consultant based service. No respondents always obtained written consent to unlicensed use, and only a minority (<5%) always obtained verbal consent, documented unlicensed use in the patient's notes, or informed other professionals of it. The drugs for which these recommended practices were sometimes carried out were ketamine (58 reports), octreotide (19), ketorolac (15), midazolam (10), gabapentin (10), and amitriptylline (10). The only unlicensed drug use for which three of the services sometimes obtained written consent was gabapentin for neuropathic pain—an indication for which it became licensed in 2000.

Invited comments covered three main themes. Firstly, respondents said that, given the prevalence of unlicensed use, it is impractical to obtain written consent routinely—and that discussion of unlicensed use could create unnecessary anxiety for the patient or carer. Secondly, some respondents sought consent only when prescribing drugs whose unlicensed use was not established in the specialty. Finally, other respondents made no distinction between licensed and unlicensed use and did not obtain verbal informed consent for use of any drug.

Comment

When prescribing drugs for use outside their licence, most specialists in palliative medicine do not routinely obtain verbal or written informed consent, document the reason for unlicensed use in the patient's notes, or inform other involved professionals of unlicensed use. When they do obtain consent, it is likely to be for the use of less established drugs and to be verbal rather than written. Strict adherence to the recommendations is not welcomed by palliative care specialists because of the number of drugs involved and the burden to patients and carers.

This view is shared by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health—the use of drugs outside their licence is also common in paediatrics—which has stated that in general it is not necessary to obtain the explicit consent of parents, carers, or patients for unlicensed use. The royal college has also stated that NHS trusts and health authorities should support therapeutic practices that are advocated by a respectable, responsible body of professionals.4,5

Figure.

Questionnaire on unlicensed use of drugs that was sent to palliative medicine specialists, with numbers (percentages) of responses (n=117) to multiple choice questions

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Atkinson CV, Kirkham SR. Unlicensed uses for medication in a palliative care unit. Palliat Med. 1999;13:145–152. doi: 10.1191/026921699676057177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todd J, Davies A. Use of unlicensed medication in palliative medicine. Palliat Med. 1999;13:446. doi: 10.1177/026921639901300517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen PJ. Off-label use of prescription drugs: legal, clinical and policy considerations. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1997;14:231–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.1997.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Medicines for children. London: RCPCH; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conroy S, Choonara I, Impicciatore P, Mohn A, Arnell H, Rane A, et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. BMJ. 2000;320:79–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]