Abstract

Background:

Algeria is among the most affected Mediterranean countries by leishmaniasis due to its large geographic extent and climatic diversity. The current study aimed to determine the ecological status (composition and diversity) of phlebotomine sandfly populations in the region of Oum El Bouaghi (Northeast Algeria).

Methods:

An entomological survey was conducted during the period May–October 2010 in rural communities of Oum El Bouaghi. Catches of sandflies were carried out using sticky traps in both domestic and peri-domestic environments of 16 sites located beneath two bioclimatic areas, sub-humid and semi-arid. Most of these sites have visceral and/or cutaneous leishmaniasis cases.

Results:

A total of 1,363 sandflies were captured and identified. They belong to two genera, Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia, and five species. The species Phlebotomus perniciosus, P. perfiliewi and Sergentomyia minuta were constants. Phlebotomus longicuspis was common and P. papatasi was accidental in the study sites. P. perniciosus and P. perfiliewi are the two possible species that contribute in leishmaniasis transmission across the study area due to their high densities (96 and 49 specimens/m2/night, respectively); these two species dominate other species in all study sites.

Conclusion:

Findings emphasize the key-role played by P. perniciosus, P. perfiliewi and S. minuta in outlining site similarities based on sandfly densities. The study confirms that the more susceptible sites to leishmaniasis, which hold high densities of these sandflies, were located south of the study area under a semi-arid climate.

Keywords: Phlebotomine sandflies, Leishmaniasis, Ecological aspects, Algeria

Introduction

Phlebotomine sandflies, vectors of leishmaniasis, are nematoceran diptera of the family Psychodidae where they constitute the sub-family Phlebotominae that includes about 900 species widely distributed over tropical and temperate regions, of which no more than 70 have been implicated in leishmaniasis transmission ( Ready 2013). These insects have been studied with considerable attention and they took a major global importance because of their role in the transmission of pathogens responsible for bartonellosis, arboviroses and leishmaniasis ( Dolmatova and Demina 1971, Tesh 1988, Depaquit et al. 2010). According to Kamhawi (2006), about 350 million people are at risk of contracting the leishmaniasis and some 2 million of new cases occur each year, mostly in developing countries.

In Algeria, 22 species of sandflies are recorded and identified, with 10 belong to the genus Sergentomyia França and Parrot 1920 and 12 to the genus Phlebotomus Rondani 1840 ( Belazzoug 1991). The geographical distribution of sandfly species seems to be closely related to the type of climate, and consequently the distribution of Leishmania transmitted by those species, which have established host-specificity in the relationship of vector–parasite such as P. papatasi Scopoli 1786 with Leishmania major Yakimoff and Schokhor 1914 and P. perniciosus Newstead 1911 with Leishmania infantum Nicolle 1908. This feature outlines clinical aspects of leishmaniasis worldwide and allows defining risk areas corresponding to the vector in question.

Like all Mediterranean countries, both canine (LCan) and human (HL) leishmaniasis affect Algeria. The first type concerns the entire country with parasitic prevalence that varies from one region to another ( Harrat et al. 1995). The HL is prevalent in two distinct forms, visceral leishmaniasis (VL) and cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). The latter is observed in three clinical aspects caused by three different parasites: (i) in the steppe and Saharan regions rife the zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL) of L. major MON-25 where Phlebotomus papatasi is the vector ( Sergent et al. 1926, Izri et al. 1992) and Gerbillidae rodents, especially Meriones shawi and Psammomys obesus are the main reservoir of the disease ( Belazzoug 1983, Belazzoug 1986, Izri et al. 1992, Harrat and Belkaid 2003, Boudrissa et al. 2012), (ii) the ZCL caused by L. infantum, where the responsible zymodemes are MON-1, MON-24, MON-80 ( Belazzoug 1982, Belazzoug et al. 1985, Harrat et al. 1995, Harrat et al. 1996) is located in Northern Algeria under sub-humid and semi-arid bioclimatic conditions where it is transmitted by P. perfiliewi Parrot 1930 ( Izri and Belazzoug 1993) and domestic dogs are the main reservoir ( Maroli et al. 1988, Benikhlef et al. 2001, Benikhlef et al. 2004), (iii) the third form is the ZCL due to L. killicki Wright 1903 MON-301 discovered in 2005 in Southern Algeria at Ghardaia ( Harrat et al. 2009) and a new variant enzymatic of L. killicki, MON-306 that has been recently identified in Annaba at the extreme Northeastern of Algeria ( Mansouri et al. 2012).

Regarding the human visceral form (VL), the responsible zymodemes are MON-1, MON-24, MON-33, MON-34, MON-78 and MON-80 ( Harrat et al. 1996). While the proven vector is P. perniciosus ( Parrot et al. 1930, Ben Ismail et al. 1987, Izri et al. 1990, Belazzoug 1992, Izri et al. 1992), the main reservoir is the dog, which was found infested with the zymodemes MON-1, MON-34, MON-77 and MON-24 ( Benikhlef et al. 2001, Benikhlef et al. 2004).

These zoonotic diseases were observed in 41 of 48 provinces in the country, which are undergoing in the last decades an epidemiological upheaval with outbreaks of new infection foci of L. major. The distributional range of these foci is extending to coastal areas in the north, since it crossed the barrier of the Tellian Atlas range for the first time in 2004 ( Boudrissa et al. 2012).

A marked increase in the number of cases of both cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis, such as those recorded from 2000 to 2004, where 30,541 cases of CL and 584 cases of VL were reported at national scale. This increase in infections is probably explained by the extension of classical foci on one hand and the emergence of new foci across the country on the other hand (INSP 2011). Similarly, the department of Health and population (DHP) at the region of Oum El Bouaghi (OEB) in Northeastern Algeria reported increasing numbers of CL and IVL “infantile visceral leishmaniasis”, where these diseases are widespreading on the majority of municipalities.

Within this context, the present study focuses on the determination of ecological status of sandfly populations in the region of OEB, particularly by answering the following questions: What is the composition and diversity of the sandfly fauna of the area studied? What are their densities and frequencies of occurrence in different localities of the region? What are the spatial similarities of sandfly species composition and density of these communities?

This systematic and ecological study aims to provide information on phlebotomine populations to guide the establishment of control and preventive programs against leishmaniasis in this region through delineating the relationships between the spatial distribution of these insects and that of leishmaniasis.

Materials and Methods

Study area and sampling sites

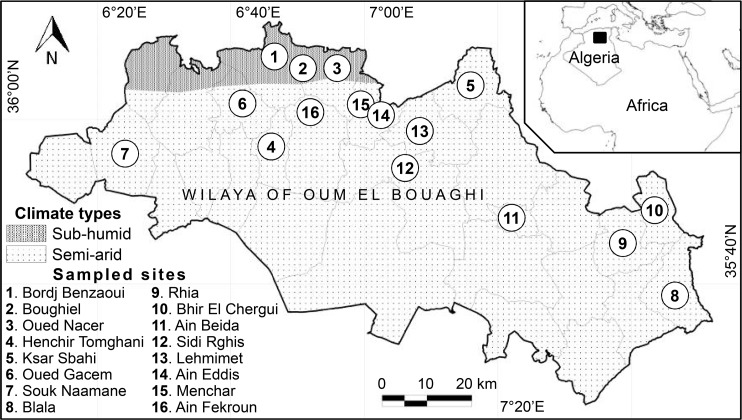

The territory of the province of Oum El Bouaghi is located between 35°24′ to 35°14′ north for latitude and 5°59′ to 7°56′ east for longitude, with an altitude ranging between 700 and 1000 m above sea level. Located between the Tellian Atlas to the North and the Saharan Atlas to the South, it occupies a central position at the region of Hauts-Plateaux in East Algeria. Administratively, the province of OEB consists of 12 sub-provinces “daïra” and 29 municipalities, with a total area of 6,783 km2 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Geographic and bioclimatic locations of the study sites in the region of Oum El Bouaghi (Northeastern Algeria)

The general climate is continental Mediterranean semi-arid. The summers are hot and dry and winters are cold. The utilized agricultural area (UAA), with an area of 361,688 ha, represents 62.36 % of the total agricultural area, including 35,520 ha of irrigated lands. This outlines it high potential for agricultural development, including wheat and barley that are cultivated without irrigation on these vast high plains.

In this region, the study concerned 16 rural sites located under semi-arid and sub-humid bioclimatic zones (Fig. 1). Among these sites, some affected by the one or the other form of leishmaniasis (CL and LV), otherwise the two forms at a time, other sites until 2010 were free of these diseases.

Trapping techniques

Entomological surveys were conducted at each site at irregular intervals between May and October 2010 using the method of sticky traps. Each trap consists of a sheet of extra white paper (21 × 29.7 cm) impregnated with purified castor oil. This method allows the census of insects and exploring resting and egg-laying habitats that stretch over large areas. It is very interesting in quantitative sampling, because it significantly reduces the personal coefficient inherent for manual techniques ( Rioux et al. 1967).

At each study site, a variable set of traps (5–20 traps) were installed simultaneously in domestic and peri-domestic habitats: (i) domestic habitats consist mainly of the courtyards where people generally spend the night during the hot season. The oily adhesive papers “sticky traps”, strained or in garland were hung on trees, outside house-windows and all high openings, (ii) in the peri-domestic habitats and in various locations spread around homes (stables, half-covered sheepfolds, rocks, ruined chambers used to collect manure or straw stock), sticky traps were placed on the walls, hanging to the roof, put in tight and sometimes profound spaces, or left between rocks. Various domestic animals are raised there: dairy cows, sheep, goats, donkeys, dogs, cats, chickens and guinea fowls.

Placed at any time of the day, traps were retained in the selected locations and then recovered after one to three nights of sampling. The number of traps retrieved with catches varied in each sampled point. Because some traps were lost or destroyed, sometimes they were taken by the wind or eaten by goats and/or rodents. Therefore, the actual number of traps was that recovered intact with insects. Because the number of traps was not the same on all the sampling points, the catches in different localities, the density of sandflies (D) was standardized and calculated as the number of specimens caught total surface of traps retrieved / number of sampling nights.

With the help a fine brush, captured sand-flies were collected and preserved in ethyl alcohol at 95° in tubes to proceed to the identification of species. The identification was carried out according to identification keys of the Phlebotomine sandflies of Algeria ( Dedet et al. 1984, Belazzoug 1991).

Data Analyses

To study characteristics of sandfly populations of each site and to enable their comparison between the study sites, the following parameters and ecological indices were calculated:

– Relative abundance (RA), expressed by the ratio between numbers of specimens of a species i and the total number of specimens caught in the site ×100.

– Degree of presence or occurrence (C)= Number of sites containing species i / total number of study sites ×100. According to occurrence value, sandfly species were classified into four groups: constant species are present in 50 % or more of study sites, common species are those whose occurrence varies between 25 and 49 %, accidental species are present in 12.5–24 % of samples, very accidental species have an occurrence of less than 12.5 % ( Neffar et al. 2015).

– Density (D): the density of sandfly species was expressed by the number of specimens captured per square meter of sticky traps per night (specimens/m2/night).

– Species richness (SR): total number of species per site ( Spellerberg and Fedor 2003).

– Jaccard similarity index (CJ) was used to compare species richness of sandflies between sampled sites taken in pairs. Given two sites, A and B, CJ was estimated as: CJ= c(a+b–c). Where a and b: the total number of species present in site A and B, respectively, c: the number of species found in both sites A and B ( Magurran 2004).

– The specific biodiversity of study sites was measured by Simpson’s diversity index (IS), which expresses the relationship between the number of species and the number of specimens simultaneously: IS= 1/(∑ Pi2), where Pi is the proportion of the species i in a given site (Pi= RA/100). The values of this index range from 1 to SR (total number of sandfly species of the site in question), with larger values indicating a higher species diversity.

– Evenness (E): E= (IS–1)/(SR–1) was computed to estimate organizational distribution of sandfly population within each site community. Site E varied from 0 (signifying the dominance of one species) to 1 (all species populations equitably distributed) ( Spellerberg and Fedor 2003).

Statistical analyses

To test the null hypothesis that there is no difference in the number and density of caught sandflies as well diversity indices (SR, IS, E) between the sixteen sampled sites, Pearson’s Chi-square test (χ2) was carried out at a threshold alpha = 0.05.

Agglomerative hierarchical clustering (AHC) was applied to cluster the sampled sites according to their similarities of sandfly species densities based on Euclidian distance. The technique used in agglomeration was Ward’s method. After that, a descriptive statistical analysis, using correspondence analysis (CA), was performed to determine segregation degree of sandfly species (considering their densities) upon the 16 surveyed sites.

Results

Species abundance and spatial occurrence

A total of 1363 specimens of sandflies were collected and morphologically classified into five species as follows: Phlebotomus (Larroussius) perniciosus dominated with 651 caught specimens (47.8%), followed by Sergentomyia (Sergentomyia) minuta Rondani 1843 caught with 385 specimens (28.2%), P. (L.) perfiliewi Parrot, 1939 with 301 specimens (22.1%). Whereas P. (L.) longicuspis Nitzulescu 1930 and P. (P.) papatasi were slightly trapped with 1.5 % and 0.4 % of total captures, respectively. Densities of the trapped sandflies were very uneven, the most important were recorded in sites of Oued Nacer, Henchir Tomghani, Rhia, Boughiel, Ksar Sbahi, and Ain Fekroun with respectively 22.73, 18.76, 17.36, 16.40, 16.29, 15.10 specimens/m2/night. Whereas densities of captures (specimens m2/ night) were low in others study sites such as in Lehmimet (9.03), Bordj Benzaoui (8.65), Ain Eddis (6.25), and Sidi Rghis (1.32) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of phlebotomine species caught by sticky traps in 16 rural sites of Oum El Bouaghi region (Northeast Algeria) during the period May–October 2010

| Study Sites | Sticky traps | Phlebotomus perniciosus | Phlebotomus perfiliewi | Phlebotomus longicuspis | Phlebotomus papatasi | Sergentomyia minuta | All sandfly species | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (m2) | nights | N | RA | D | N | RA | D | N | RA | D | N | RA | D | N | RA | D | N | D | |

| S1 | 3.12 | 1 | 5 | 18.52 | 1.60 | 22 | 81.48 | 7.05 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 27 | 8.65 |

| S2 | 4.94 | 2 | 58 | 35.80 | 5.87 | 97 | 59.88 | 9.82 | – | – | – | – | – | 7 | 4.32 | 0.71 | 162 | 16.40 | |

| S3 | 2.64 | 3 | 87 | 48.33 | 10.98 | 84 | 46.67 | 10.61 | 3 | 1.67 | 0.38 | 2 | 1.11 | 0.25 | 4 | 2.22 | 0.51 | 180 | 22.73 |

| S4 | 6.13 | 1 | 100 | 86.96 | 16.31 | 6 | 5.22 | 0.98 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 9 | 7.82 | 1.47 | 115 | 18.76 |

| S5 | 2.64 | 4 | 44 | 25.58 | 4.17 | 36 | 20.93 | 3.41 | 1 | 0.58 | 0.09 | 2 | 1.16 | 0.19 | 89 | 51.75 | 8.43 | 172 | 16.29 |

| S6 | 3.60 | 1 | 18 | 45.00 | 5.00 | 18 | 45.00 | 5.00 | 1 | 2.50 | 0.28 | – | – | – | 3 | 7.50 | 0.83 | 40 | 11.11 |

| S7 | 3.16 | 3 | 5 | 4.42 | 0.53 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 108 | 95.58 | 11.39 | 113 | 11.92 |

| S8 | 4.88 | 2 | 68 | 95.77 | 6.97 | 1 | 1.41 | 0.10 | 1 | 1.41 | 0.10 | – | – | – | 1 | 1.41 | 0.10 | 71 | 7.27 |

| S9 | 4.32 | 3 | 77 | 34.22 | 5.94 | – | – | – | 2 | 0.89 | 0.15 | – | – | – | 146 | 64.89 | 11.27 | 225 | 17.36 |

| S10 | 10.08 | 2 | 111 | 79.29 | 5.51 | 16 | 11.43 | 0.79 | – | – | – | 1 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 12 | 8.59 | 0.60 | 140 | 6.94 |

| S11 | 2.00 | 3 | 33 | 63.46 | 5.50 | 2 | 3.85 | 0.33 | 11 | 21.15 | 1.83 | – | – | – | 6 | 11.54 | 1.00 | 52 | 8.67 |

| S12 | 1.52 | 1 | 2 | 100 | 1.32 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 1.32 |

| S13 | 1.44 | 1 | 9 | 69.23 | 6.25 | 4 | 30.77 | 2.78 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 13 | 9.03 |

| S14 | 1.60 | 1 | 10 | 100 | 6.25 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10 | 6.25 |

| S15 | 1.60 | 1 | 12 | 100 | 7.50 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12 | 7.50 |

| S16 | 1.92 | 1 | 12 | 41.38 | 6.25 | 15 | 51.72 | 7.81 | 2 | 6.90 | 1.04 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 29 | 15.10 |

| Chi2 value (df = 15) | 520.83 | 247.50 | 35.13 | 714.65 | 475.00 | 71.50 | 86.43 | 184.70 | 15.52 | 23.80 | 13.60 | 2.83 | 1328.75 | 769.30 | 110.35 | 935.21 | 41.56 | ||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.414 | 0.069 | 0.559 | 0.999 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Total N | 651 | 301 | 21 | 5 | 385 | 1363 | |||||||||||||

| Percentage of N | 47.8 | 22.1 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 28.2 | 100 | |||||||||||||

| Total of D | 95.95 | 48.68 | 3.87 | 0.49 | 36.31 | 185.30 | |||||||||||||

| Mean D | 6.00 | 3.04 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 2.27 | 11.58 | |||||||||||||

| Mean of RA | 59.26 | 22.38 | 2.21 | 0.19 | 15.96 | ||||||||||||||

| Occurrence (%) | 100 | 68.75 | 43.8 | 18.8 | 62.5 | ||||||||||||||

| Occurrence class | Constant | Constant | Common | Accidental | Constant | ||||||||||||||

N: Number of caught specimens, RA: Relative abundance (species % per site), D: species density (specimens/m2/night) (See Fig. 1 for site codes).

Phlebotomus perniciosus was the most constant species, which showed the widest geographic distribution due to its high frequency of occurrence (C= 100%). Caught in all surveyed sites, it was followed by P. perfiliewi that was widespread too. Indeed it was observed in eleven sites on sixteen that equals C= 68.75%. The third species that had an important presence was S. minuta (C= 62.50%). While P. longicuspis was poorly represented (4.14% of the genus P. and only 3.2 % of overall specimens), but it was sprinkled over seven of the sixteen study sites, its degree of presence C= 43.8%. The lowest occurrence frequency was recorded for P. papatasi that was captured in three sites (C= 18.75%), which makes it an accidental species in the region.

Diversity and similarity

Generally, species richness per site was relatively low, it varied between one species (SR= 1) in three sites and SR= 5 in Oued Nacer and Ksar Sbahi. The spatial distribution of species richness values was uneven along the study area. Southern sites were richer in species number than sites located in the north of OEB. Simpson’s index showed a slight diversity in all sites. This was confirmed by evenness (E) values calculated in the study sites, which may be grouped into three categories: the first (0≤ E< 0.37) includes a single dominant species; in the second (0.37≤ E< 0.5), two species co-dominated, and finally sites where evenness varied between 0.5 and 0.8, including three species co-dominated (Table 2). The Chi-squared test revealed no differences (P> 0.05) between the study sites for values of all parameters of diversity (SR, IS, E).

Table 2.

Spatial distribution of diversity indices of sandfly species and their dominance in the study sites at Oum El Bouaghi area (Northeast Algeria) during 2010

| Surveyed sites | SR | IS | E | Dominant species (RA in %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bordj Benzaoui | 2 | 1.43 | 0.43 | P. perfiliewi (81.5) |

| Boughiel | 3 | 2.12 | 0.56 | P. perfiliewi (59.9), P. perniciosus (35.8) |

| Oued Nacer | 5 | 1.92 | 0.23 | P. perniciosus (48.3), P. perfiliewi (46.7) |

| Henchir Tomghani | 3 | 1.00 | 0 | P. perniciosus (86.9) |

| Ksar Sbahi | 5 | 2.77 | 0.29 | S. minuta (51.7), P. perniciosus (25.6), P. perfiliewi (20.9) |

| Oued Gacem | 4 | 2.12 | 0.37 | P. perniciosus (45.0), P. perfiliewi (45.0) |

| Souk Naamane | 2 | 1.00 | 0 | S. minuta (95.9) |

| Blala | 4 | 1.08 | 0.02 | P. perniciosus (95.8) |

| Rhia | 3 | 1.85 | 0.42 | S. minuta (64.9), P. perniciosus (34.2) |

| Bhir Chergui | 4 | 1.50 | 0.16 | P. perniciosus (79.3) |

| Ain Beida | 4 | 2.22 | 0.40 | P. perniciosus (63.5), P. longicuspis (21.2) |

| Sidi Rghis | 1 | 1.00 | 0 | P. perniciosus (100) |

| Lehmimet | 2 | 1.78 | 0.78 | P. perniciosus (69.2) , P. perfiliewi (30.8) |

| Ain Eddis | 1 | 1.00 | 0 | P. perniciosus (100) |

| Menchar | 1 | 1.00 | 0 | P. perniciosus (100) |

| Ain Fekroun | 3 | 2.27 | 0.63 | P. perfiliewi(51.7), P. perniciosus(41.4) |

| 9.17 | 11.16 | 9.56 | ||

| P | 0.868 | 0.741 | 0.846 | |

(SR: species richness, IS: Simpson index, E: evenness, RA: relative abundance)

Values of Jaccard’s index fluctuated between 0.20 and 1. In 32.1 % of pair similarities, resemblance value between sites was high than 0.50. The highest value of similarity reached 1 in 18 of 240 comparison cases, where the high values of similarity were recorded between sites with high numbers of species. Inversely the dissimilarity was higher between the sites of low SR, where 8.75 % of cases showed similarity values less than 0.33 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Matrix of proximity applied for sandfly similarity between the 16 sampled sites considered in pairs. The values are referred to the number of shared species (above the diagonal) and Jaccard’s similarity index “CJ” (under the diagonal)

| Sites | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | S11 | S12 | S13 | S14 | S15 | S16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2) | (3) | (5) | (3) | (5) | (4) | (2) | (4) | (3) | (4) | (4) | (1) | (2) | (1) | (1) | (3) | |

| S1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| S2 | 0.67 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| S3 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| S4 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| S5 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| S6 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| S7 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| S8 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| S9 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| S10 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| S11 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| S12 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| S13 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| S14 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1 | 1 | |

| S15 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1 | |

| S16 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.75 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

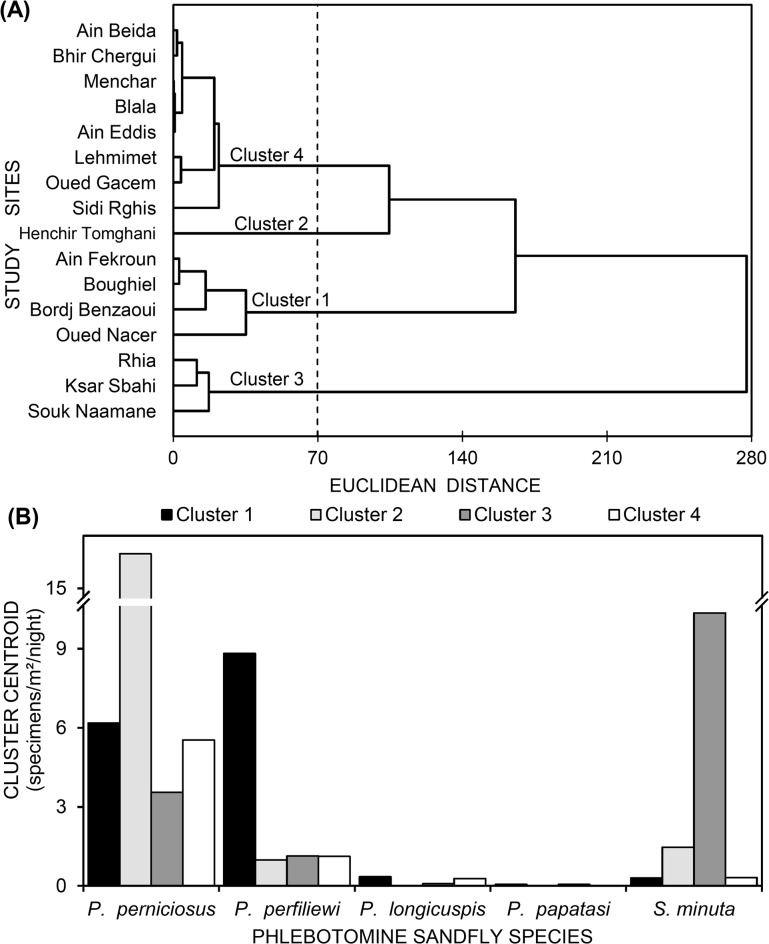

The sixteen sampled sites were clustered according to Euclidean distances into four different classes: (i) the first group gathered sites located in the North of OEB, basically under sub-humid climate, including Bordj Benzaoui, Boughiel, Oued Nacer, and Ain Fekroun, (ii) the site of Henchir Tomghani was plotted as a single class, (iii) the 3rd class included three sites located at the periphery of OEB region, namely Ksar Sbahi, Souk Naamane and Rhia, and (iv) the fourth cluster was represented by the rest of the study sites (Fig. 2A). From the point of view of species contribution in the segregation of clusters of the sampled sites, P. perniciosus had an important contribution to the distinction between the four clusters, especially for the second cluster. Whilst the density of P. perfiliewi characterized especially cluster 1, the density of S. minuta singularized the third cluster of sites. However, densities of P. longicuspis and P. papatasi had slight contribution in cluster differentiation (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Agglomerative hierarchical clustering (AHC) displaying similarities (Euclidian distance, linkage rule: Ward’s method) among sandfly densities captured from 16 sites in Oum El Bouaghi (Northeast Algeria). (A): Dendrogram of the AHC, (B): variation of cluster centroids following phlebotomine sandfly densities

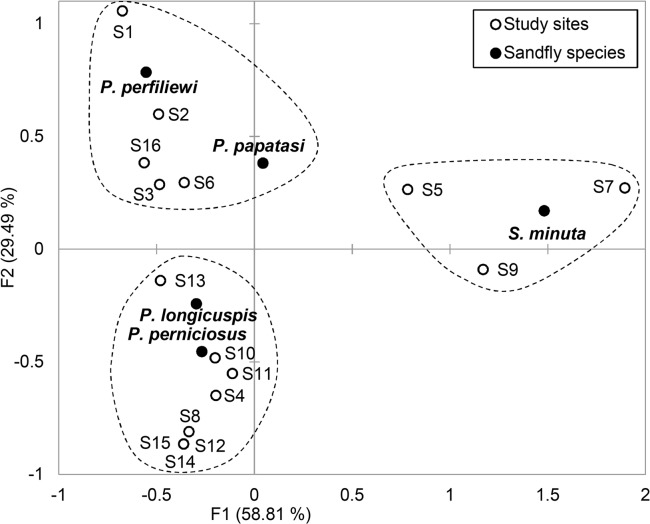

Correspondence analysis (CA), applied to sandfly species densities in relation with different sampled sites, was represented on the factorial symmetric plot of two axes F1 × F2 with the maximum of inertia (88.3% hereafter). The CA showed that the x-axis (F1= 58.81%) separated sites of Ksar Sbahi, Souk Naamane and Rhia, which were characterized by S. minuta. Whereas y-axis (F2= 29.49%) distinguished two groups of sites, the first included basically sites located under sub-humid climatic conditions (i.e. Bordj Benzaoui, Boughiel, Oued Nacer, Ain Fekroun and Oued Gacem) characterized by P. perfiliewi and P. papatasi, the second gathered the eight left sites that are marked by high densities of P. perniciosus and P. longicuspis (Fig. 3). Thus, these sites (i.e. Ain Beida, Ain Eddis, Bhir El Chergui, Blala, Henchir Tomghani, Lehmimet, Menchar, Sidi Rghis) are the more susceptible for the disease. Overall, while the x-axis separated site groups according to the degree of variability in sandfly species densities, the y-axis highlighted the involvement of climatic characteristics in the distinction between two sets of sites, one located under hub-humid climate and the other under semiarid climate.

Fig. 3.

Factorial plot of the classification analysis (CA) applied to the distributions of densities of sandfly species on sampled sites of Oum El Bouaghi (North Algeria) in 2010. (Codes of the study sites are reported in Fig. 1)

Relationship between species of subgenus Larroussius and leishmaniasis cases

To identify and confirm the relationship between the occurrence of leishmaniasis cases registered by the Direction of Health and Population (DSP, 2013) at different localities of OEB for the period between 1998 and 2009 and densities of phlebotomine sandflies captured at their surroundings, we calculated rates and proportions of different species of the subgenus Larroussius, whose vector role was known and confirmed. Results of these calculations revealed a close relationship and a concordance between the high presence of P. perniciosus and P. perfiliewi and the occurrence of leishmaniasis cases in the study sites (Table 4).

Table 4.

Relationship between species of the subgenus Larroussius collected in OEB region (May–October 2010) and leishmaniasis cases (1998–2009)

| Study sites | Type of Leishmaniasis | Total of catch | Total within Larroussius | Number among Larroussius (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. perniciosus | P. perfiliewi | P. longicuspis | ||||

| Bordj Benzaoui | CL + LCan | 27 | 27 | 05 (18.51) | 22 (81.49) | – |

| Boughiel | CL + LCan | 162 | 155 | 58 (37.41) | 97 (62.59) | – |

| Oued Nacer | CL | 180 | 174 | 87 (50.00) | 84 (48.28) | 03 (1.72) |

| Henchir Tomghani | CL + IVL | 115 | 106 | 100 (94.33) | 06 (5.67) | – |

| Ksar Sbahi | CL + IVL | 172 | 81 | 44 (54.32) | 36 (44.44) | 01 (1.24) |

| Oued Gacem | IVL | 40 | 37 | 18 (48.65) | 18 (48.65) | 01 (2.70) |

| Souk Naamane | – | 113 | 05 | 05 (100) | – | – |

| Blala | – | 71 | 70 | 68 (97.14) | 01 (1.43) | 01 (1.43) |

| Rhia | IVL | 225 | 79 | 77 (97.47) | – | 02 (2.53) |

| Bhir Chergui | IVL | 140 | 127 | 111 (87.40) | 16 (12.60) | – |

| Ain Beida | IVL | 52 | 46 | 33 (71.74) | 02 (4.35) | 11 (23.91) |

| Sidi Rghis | – | 02 | 02 | 02 (100) | – | – |

| Lehmimet | – | 13 | 13 | 09 (69.23) | 04 (30.77) | – |

| Ain Eddis | – | 10 | 10 | 10 (100) | – | – |

| Menchar | CL | 12 | 12 | 12 (100) | – | – |

| Ain Fekroun | CL | 29 | 29 | 12 (41.38) | 15 (51.72) | 02 (6.90) |

(CL: cutaneous leishmaniasis, VL: visceral leishmaniasis, LCan: canine leishmaniasis, IVL: infantile visceral leishmaniasis)

Discussion

The sampling of sandflies that was carried out using sticky traps has revealed the presence of five species of the 22 species already known in Algeria ( Dedet et al. 1984). These five species belong to two genera: Phlebotomus (4) and Sergentomyia (1), the latter is characterized by its herpetophilic feeding behaviour ( Dedet et al. 1984, Berchi 1990). At OEB, genus Sergentomyia is represented by the species S. minuta sub-species parroti Adler and Theodor 1927 (RA= 28.24%, C= 62.50%) that dominates in rural peri-domestic habitats of Ksar Sbahi and Souk Naamane. Landscapes of these habitats are formed of hedges of prickly pear plantations (Opuntia ficusindica), which are rich environments by Lacertidae species.

Although Sergentomyia minuta has been found negative for human and cow infection during the analysis of blood meals (Yaghoobi et al. 1995, Dancesco 2008), some species of the genus Sergentomyia (Sergentomyia dubia, S. magna, S. schewtzi) are suspected in the transmission of LCan in Senegal because of their high presence inside and around homes and in the narrow circle of the dog ( Senghor et al. 2011). In fact, this suspicion was confirmed when three females of the genus Sergentomyia were found naturally infected by L. infantum; it is S. dubia, S. magna and S. schwetzi, highlighting the distribution significantly associated with the prevalence of dogs in the focus of Mont-Rolland ( Senghor et al. 2011). These findings challenge the dogma that states that only the genus Phlebotomus is responsible for the transmission of leishmaniasis in the Old World and criminalize genus Sergentomyia in the epidemiology of this zoonosis.

Moreover, the high occurrence of species belonging to genus Sergentomyia has been reported in several countries, including France and Tunisia ( Croset 1969), Algeria ( Dedet et al. 1984, Belazzoug 1986), Tunisia ( Ghrab et al. 2006), and Senegal ( Senghor et al. 2011).

Among the five species collected at OEB, four belong to the genus Phlebotomus, proven vector of HL in the old world. These species are distributed on two sub-genera Larroussius and Phlebotomus. The subgenus Larroussius is proven vector of L. infantum in the Mediterranean region (Killick-Kindrick 1985, Killick-Kindrick 1990). While the sub-genus Phlebotomus is represented by a single species, P. papatasi, which is the main vector of L. major MON-25 (Killick-Kindrick 1990, Izri et al. 1992, Harrat and Belkaid 2003). This species, that forms only 0.4 % of total, is found in three sites with low occurrence (C= 18.75%), which gives it an accidental status, thus its role in the transmission of CL in the area is very remote.

The dominance of species of subgenus Larroussius (RA= 71.38% of the total catches, RA= 99.48% of the genus Phlebotomus), reflects the significant abundance and wide geographical distribution of these species. The species P. perniciosus (RA= 47.76% of the overall results, RA= 66.90% of the subgenus Larroussius) is not only omnipresent in all study sites (C= 100%), but reported dominant in 11/16 of studied sites. This reflects its high ecological valence and its adaptive capacities in the region. Moreover, its distributional area matches that of HL and LCan ( Addadi and Dedet 1976). Regarding this species, our results confer with those reported par Berchi et al. (2007) where P. perniciosus was more abundant in catches carried out in peri-domestic areas of Mila and Jijel. The role of this species in the transmission of IVL and LCan is confirmed in several regions of the Mediterranean basin ( Bettini et al. 1986, Ben Ismail et al. 1987, Maroli et al. 1988, Izri et al. 1990, Izri et al. 1992, Belazzoug 1992, Janini et al. 1995).

In addition, the species P. perfiliewi is largely widespread and constant in the study area (RA= 20.46%, C= 68.75%), where it co-dominates next to P. perniciosus. Indeed, the species is reported as dominant in two sites in the sub-humid bioclimatic area (Bordj Benzaoui and Boughiel) and Ain Fekroun in semi-arid climate. It is the proven vector of L. infantum in Algeria ( Izri and Belazzoug 1993, Benikhlef et al. 2004) and Italy ( Maroli et al. 1988).

As for P. longicuspis, an endemic species in Algeria and North Africa ( Dedet et al. 1984, Killick-Kindrick 1999), is very abundant with P. perniciosus in peri-domestic environments ( Berchi et al. 2007). It was captured around dog locations ( Croset 1969), where its feeding behaviour is very similar to that of P. perniciosus ( Croset et al. 1970). The males of this species have been confused with P. perniciosus ( Berchi et al. 2007, Boussaa et al. 2007). At OEM, P. longicuspis is represented by only 43 specimens (RA= 3.15%) of which 40 were identified as males. Its role in the epidemiology of leishmaniasis is not excluded, as all species of the subgenus Larroussius in the Mediterranean basin are anthropophilic and endophilic. Indeed, these species sting indoors seven times they do outside ( Izri et al. 1993, Killick-Kindrick 1999).

The noteworthy presence of P. perniciosus and P. perfiliewi, proven vector species of leishmaniasis, could explain the sporadic cases of VL and CL in OEB. Their presence in domestic and peri-domestic environments (such as courtyards, stables, rooms and exterior walls of abandoned houses) and in the immediate vicinity of homes confirm their both endo-exophilic and anthropozoophilic characters. Moreover, their important frequencies represent a potential risk factor and at the same time a valuable bio-indication of endemicity. As the risk of disease spreading increases with the increase of vector densities, thus the larger sandfly densities are, the higher the rate of people who could be infected is important.

According Euzeby (1984), a minimum density of 10 to 15 sandflies/m2 is required to maintain the endemic of leishmaniasis. This threshold is reached at eight surveyed sites in OEB, where the highest densities were observed at Oued Nacer, Henchir Tomghani, Rhia, Boughiel, Ksar Sbahi, and Ain Fekroun with 22.73, 18.76, 17.36, 16.40, 16.29, 15.10 specimens/m2/night, respectively.

However, medium or low density of sandflies in the other study sites is very probably due to the phenology of species during the study period as well as local climatic conditions, including temperature, precipitation and wind speed, which play the role of limiting factor for many flying insects ( Compton et al. 2002).

Overall, the exploration of some localities in the region of OEB revealed a low diversity (five species), compared with the 22 known species in Algeria. Very similar results were denoted in Eastern Algeria, where only four species have been reported in two classic foci of HL and LCan, in Constantine (Moulahem 1998) and Mila ( Messai 2011), which both are adjacent areas to OEB. In Skikda at Northern Algeria, Bouleknafed (2007) reported the presence of five species with occurrence frequencies and densities very close to our results.

In OEB, the distribution of abundance and density of sandfly species is very uneven, with significant differences between the sampled locations (significant χ2 test). Indeed some species are found in large numbers while others are represented only by few specimens (relatively low value of evenness). This variability of species frequencies is well known, where it was particularly evident based on observations on 30,000 specimens in Tunisia (Croset 1996) and in the Kabylia in North Algeria ( Izri et al. 1990).

Our findings clearly show that P. perniciosus, P. perfiliewi and S. minuta are the most consistently captured species. In addition, P. perfiliewi usually accompanies P. perniciosus around habitations and even indoors. The absence of P. perfieliwi is spotted in areas where sandfly catches are so low. The distribution and/or occurrence of P. perniciosus matches regions that are almost all involved in the one or the other form of leishmaniasis, or both types at once (as the case of Ksar Sbahi and Henchir Tomghani). The presence of sandflies in abundance increases susceptibility to leishmaniasis in localities in question. For example, the region of Oued Gacem, that was until 2010 free of leishmaniasis, was stated positive for P. perniciosus and P. perfiliewi in peri-domestic environments; has just know two cases of IVL, one in 2012 and the other in 2013 (DSP, 2013).

It is likely that P. perniciosus represents the main vector of leishmaniasis in the study area, as it has been reported in the Mediterranean countries ( Bettini et al. 1986, Maroli et al. 1988, Izri et al. 1990, Izri et al. 1992). However, the high frequency of P. perfiliewi (20.46%) with a presence in 68.75 % of the study sites next to P. perniciosus suggests that more than one species may be implicated in the transmission of HL and LCan ( Izri et al. 1992). Indeed, P. perfiliewi is proven vector of L. infantum MON-24, the causative agent of ZCL and LCan in Algeria ( Izri and Belazzoug 1993, Benikhlef et al. 2004).

Conclusion

Phlebotomus perniciosus and P. perfiliewi are the most likely species that transmit leishmaniasis in the region of OEB due to their high density and constant spatial occurrence. Their massive presence in domestic and peri-domestic environments is a potential risk factor and a valuable bio-indication for an effective control against these zoonotic diseases. The present study is a contribution to the ecological study of sand-flies of Eastern Algeria and at the same time an initiation to the study of entomological aspects of leishmaniasis in the region of OEB.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Dr Said Chawki Boubidi and Dr Abdelkarim Boudrissa for their valuable helps in the identification of phlebotomine sandflies. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. This study did not receive any funding.

References

- Addadi K, Dedet JP. (1976) Epidémiologie des leishmanioses en Algérie. 6 Recensements des cas de leishmanioses viscérales infantiles entre 1965 et 1974. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 69: 68– 75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belazzoug S. (1982) Une épidémie de leishmaniose cutanée dans la région de M’sila (Algérie). Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 75( 5): 497– 504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belazzoug S. (1983) Le nouveau foyer de leishmaniose cutanée de M’sila (Algérie), infestation naturelle de Psammomys obesus (Rongeur, Gerbillidés). Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 76: 146– 149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belazzoug S. (1986) Découverte d’un Meriones shawi (Rongeur, Gerbillidés) naturellement infesté par Leishmania dans le nouveau foyer de leishmaniose cutanée de Ksar Chellala (Algérie). Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 79( 5): 630– 633. [Google Scholar]

- Belazzoug S. (1991) The sandflies of Algeria. Parasitol. 33: 85– 87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belazzoug S. (1992) Leishmaniasis in Mediterranean countries. Vet Parasitol. 44( 1): 15– 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belazzoug S, Lanotte G, Maazoun R. (1985) Un nouveau variant enzymatique de Leishmania infantum Nicolle, 1908, Agent de la leishmaniose cutanée du Nord de l’Algérie. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 60( 1): 1– 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ismail R, Hellal H, Bach Hamba D, Ben Rachid MS. (1987) Infestation naturelle de Phlebotomus papatasi dans un foyer de leishmaniose cutanée zoonotique en Tunisie. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 80( 4): 613– 614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benikhlef R, Harrat Z, Toudjine M, Djerbouh A, Bendali-Braham S, Belkaid M. (2004) Présence de Leishmania infantum MON-24 chez le chien. Med Trop. 64( 4): 381– 383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benikhlef R, Pratlong F, Harrat Z, Seridi N, Bendali-Braham S, Belkaid M, Dedet JP. (2001) Infantile visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum zymodeme MON-24 in Algeria. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 94( 1): 14– 16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchi S. (1990) Ecologie des phlébotomes (Diptere, Psychodidae) de l’Est algérien [Magister dissertation]. University of Constantine, Algeria. [Google Scholar]

- Berchi S, Bounamous A, Louadi K, Pesson B. (2007) Différenciation morphologique de deux espèces sympatriques: Phlebotomus perniciosus Newstead 1911 et Phlebotomus longicuspis Nitzulescu 1930 (Diptera: Psychodidae). Ann Soc Entomol Fr. 43( 2): 201– 203. [Google Scholar]

- Bettini S, Gramiccia M, Gradoni L, Atzeni MC. (1986) Leishmaniasis in Sardinia: II. Natural infection of Phlebotomus perniciosus Newstead, 1911, by Leishmania infantum Nicolle, 1908, in the province of Cagliari. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 80( 3): 458– 459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudrissa A, Cherif K, Kherrachi I, Benbetka S, Bouiba L, Boubidi SC, Benikhlef R, Arrar L, Hamrioui B, Harrat Z. (2012) Extension de Leishmania major au nord de l’Algérie. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 105( 1): 30– 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulkenafet F, Berchi S, Louadi K. (2007) Les phlébotomes (Diptera : Psychodidae) et la transmission de la leishmaniose dans la région de Skikda. The 3rd National Workshop NAFRINET, 2007 December 2–3, University of Tebessa, Algeria: pp. 34– 39. [Google Scholar]

- Boussaa S, Pesson B, Boumezzough A. (2007) Phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae) of Marrakech city, Morocco. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 101 ( 8): 715– 724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton SG, Bullock JM, Kenward RE, Hails RS. (2002) Sailing with the wind: dispersal by small flying insects. Dispersal ecology: The 42nd Symposium of the British Ecological Society, 2–5 April 2001, University of Reading, UK, Blackwell Publishing; pp. 113– 133. [Google Scholar]

- Croset H. (1969) Ecologie et systématique des phlébotomini (Diptera : Psychodidae) dans deux foyers Français et Tunisien de leishmaniose viscérale. Essai d’interprétation épidémiologique [PhD dissertation]. University of Montpellier, France. [Google Scholar]

- Croset H, Abonnec E, Rioux JA. (1970) Phlebotomus (Paraphlebotomus) chabaudi n. sp. (Diptera: Psychodidae). Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 45: 863– 873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancesco P. (2008) Les espèces de phlébotomes (Diptera: Psychodidae) de Roumanie, certains aspects de leur écologie et nouvelles stations de capture. Trav Mus Nat Hist Nat Grigore Antipa. 51: 185– 199. [Google Scholar]

- Dedet JP, Addadi K, Belazzoug S. (1984) Les Phlébotomes (Diptera, Psychodidae) d’Algérie. Cah. ORSTOM. Ser. Entomol Med Parasitol. 22( 2): 99– 127. [Google Scholar]

- Depaquit J, Grandadam M, Fouque F, Andry PE, Peyrefitte C. (2010) Arthropod-borne viruses transmitted by Phlebotomine sandflies in Europe: a review. Euro Surveill. 15( 10): 19507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmatova AV, Demina NA. (1971) Les Phlébotomes (Phlebotominae) et les maladies qu’ils transmettent. Office de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique Outre-Mer (ORSTOM), Paris: pp. 17–63. [Google Scholar]

- DSP (2013) Périodique des maladies à déclaration obligatoire. Document interne, Service d’épidémiologie et de médecine préventive. Direction de la santé et de la population (DSP), Oum El Bouaghi, Algeria. [Google Scholar]

- Euzeby J. (1984) Les parasites humains d’origine animale. Caractères épidémiologiques. Flammarion Médecine-Sciences. Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Ghrab J, Rhim A, Bach-Hamba D, Chahed MK, Aoun K, Nouira S, Bouratbine A. (2006) Phlebotominae (Diptera: Psychodidae) of human leishmaniosis sites in Tunisia. Parasite. 13(1): 23– 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrat Z, Belkaid M. (2003) Les leishmanioses dans l’Algérois. Données épidémiologiques. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 96 (3): 212– 214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrat Z, Boubidi SC, Pratlong F, Benikhlef R, Selt B, Dedet JP, Ravel C, Belkaid M. (2009) Description of a dermatropic Leishmania close to L. killicki (Rioux, Lanotte and Pratlong 1986) in Algeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 103( 7): 716– 720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrat Z, Hamrioui B, Belkaïd M, Tabet-Derraz O. (1995) Point actuel sur l’épidémiologie des leishmanioses en Algérie. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 88( 4): 180– 184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrat Z, Pratlong F, Belazzoug S, Dereure J, Deniau M, Rioux JA, Belkaid M, Dedet JP. (1996) Leishmania infantum and L. major in Algeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 90: 625– 629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INSP (2011) Monthly Epidemiological Records (REM) of the National Institute of Public Health. Institut National de Santé Publique (INSP), Algiers, Algeria: Available from: http://www.ands.dz/insp/rem.html [Google Scholar]

- Izri MA, Belazzoug S. (1993) Phlebotomus (Larroussius) perfiliewi naturally infected with dermotropic Leishmania infantum at Tenes, Algeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 87( 4): 399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izri MA, Belazzoug S, Boudjebla Y, Dereure J, Pratlong F, Delalbre-Belmonte A, Rioux JA. (1990) Leishmania infantum MON 1, isolée de Phlebotomus perniciosus en Kabylie, Algérie. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 65( 3): 151– 152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izri MA, Belazzoug S, Pratlong F, Rioux JA. (1992) Isolement de Leishmania major chez Phlebotomus papatasi à Biskra (Algérie): fin d’une épopée écoépidémiologique. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 67( 1): 31– 32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janini R, Saliba E, Khoury S, Oumish O, Adwan S, Kamhawi S. (1995) Incrimination of Phlebotomus papatasi as vector of Leishmania major in the southern Jordan Valley. Med Vet Entomol. 9( 4): 420– 422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamhawi S. (2006) Phlebotomine sand flies and Leishmania parasites: friends or foes?. Trends Parasitol. 22( 9): 439– 445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killick-Kendrick R. (1990) Phlebotomine vectors of the leishmaniases: a review. Med Vet Entomol. 4( 1): 1– 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killick-Kendrick R. (1999) The Biology and Control of Phlebotomine Sand Flies. Clin Dermatol. 17( 3): 279– 289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killick-Kendrick R, Leaney AJ, Peters W, Rioux JA, Bray RS. (1985) Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Saudi Arabia: the incrimination of Phlebotomus papatasi as the vector in the Al Hassa oasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 79( 2): 252– 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magurran AE. (2004) Measuring biological diversity. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; pp. 100– 119. [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri R, Pratlong F, Bachi F, Hamrioui B, Dedet JP. (2012) The First Isoenzymatic Characterizations of the Leishmania Strains Responsible for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in the Area of Annaba (Eastern Algeria). Open Conf Proc J. 3: 6– 11. [Google Scholar]

- Maroli M, Gramiccia M, Gradoni L, Ready PD, Smith DF, Aquino C. (1988) Natural infection of phlebotomine sandflies with Trypanosomatidae in central and south Italy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 82( 2): 227– 228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messai N, Berchi S, Boulknafd F, Louadi K. (2011) Diversité biologique de phlébotomes (Diptera : Psychodidae) de la région de Mila. Proceeding of SIBFA 22–24 November 2009, University of Ouargla, Algeria, pp. 182– 184. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaham T, Fendri AH, Harrat Z, Benmezdad A, Aissaoui K, Ahraou S, Addadi K. (1998) Contribution à l’étude des phlébotomes de Constantine : espèces capturées dans un appartement urbain. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 91( 4): 344– 345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neffar S, Chenchouni H, Si Bachir A. (2015) Floristic composition and analysis of spontaneous vegetation of Sabkha Djendli in North-east Algeria. Plant Biosystems. DOI: 10.1080/11263504.2013.810181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrot L, Donatien A, Lestoquard F. (1930) Sur le développement du parasite de la leishmaniose canine viscéral chez P. major var perniciosus. Newstead. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 23( 7): 724– 726. [Google Scholar]

- Ready PD. (2013) Biology of phlebotomine sand flies as vectors of disease agents. Ann Review Entomol. 58: 227– 250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux JA, Golvan YJ, Croset H, Houin R, Juminer B, Bain O, Tour S. (1967) Ecologie des leishmanioses dans le sud de la France. Ann Parasitol. 42( 6): 561– 603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senghor MW, Faye MN, Faye B, Diarra K, Elguero E, Gaye O, Bañuls AL, Niang AA. (2011) Ecology of phlebotomine sand flies in the rural community of Mont Rolland (Thies region, Senegal): area of transmission of canine leishmaniasis. Plos One. 6( 3): 14773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergent E, Parrot L. (1926) Chronique du bouton d’orient. Arch Inst Pasteur Alger. 4: 26– 96. [Google Scholar]

- Spellerberg IF, Fedor PJ. (2003) A tribute to Claude Shannon (1916–2001) and a plea for more rigorous use of species diversity and the “Shannon-Wiener” Index. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 12( 3): 177– 183. [Google Scholar]

- Tesh RB. (1988) The genus Phlebovirus and its vectors. Ann Rev Entomol. 33( 1): 169– 181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Javadian E, Tahuildar-Bidruni GH. (1995) Leishmania major MON-26 isolated from naturally infected Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Isfahan Province, Iran. Acta Trop. 59( 4): 279– 282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]