Abstract

Objective:

Early intervention services (EIS) for psychosis have been developed in several countries, including Canada. There is some agreement about the program elements considered essential for improving the long-term outcomes for patients in the early phase of psychotic disorders. In the absence of national standards, the current state of EIS for psychosis in Canada needs to be examined in relation to expert recommendations currently available.

Method:

A detailed online benchmark survey was developed and administered to 11 Canadian academic EIS programs covering administrative, clinical, education, and research domains. In addition, an electronic database and Internet search was conducted to find existing guidelines for EIS. Survey results were then compared with the existing expert recommendations.

Results:

Most of the surveyed programs offer similar services, in line with published expert recommendations (i.e., easy and rapid access, intensive follow-up through case management with emphasis on patient engagement and continuity of care, and a range of integrated evidence-based psychosocial interventions). However, differences are observed among programs in admission and discharge criteria, services for patients at ultra high risk (UHR) for psychosis, patient to clinician ratios, accessibility of services, and existence of specific inpatient units. These seem to diverge from expert recommendations.

Conclusions:

Although Canadian programs are following most expert recommendations on clinical components of care, some programs lack administrative and organizational elements considered essential. Continued mentoring and networking of clinicians through organizations such as the Canadian Consortium for Early Intervention in Psychosis (CCEIP), as well as the development of a fidelity scale through further research, could possibly help programs attain and maintain the best standards of early intervention. However, simply making clinical guidelines available to care providers is not sufficient for changing practices; this will need to be accompanied by adequate funding and support from organizations and policy makers.

Keywords: early intervention, psychosis, schizophrenia, mental health services organization, government mental health policy, treatment guidelines, evidence-based practice

Abstract

Objectif:

Les services d’intervention précoce (SIP) pour la psychose se sont développés dans plusieurs pays incluant le Canada. Certains éléments sont considérés essentiels pour améliorer l’issue clinique du traitement dans les phases précoces des troubles psychotiques. En l’absence de guides de pratique nationaux, l’état actuel des SIP au Canada nécessite d’être examiné et comparé aux recommandations d’expert disponibles.

Méthode:

Un sondage détaillé a été élaboré et administré en ligne à 11 SIP universitaires canadiens. Le sondage couvrait les aspects administratifs et cliniques ainsi que la formation et la recherche. Une recherche sur les bases de données électroniques ainsi que sur Internet a été faite afin de repérer des guides de pratique existants pour les SIP. Les données recueillies lors du sondage ont été comparées aux recommandations d’expert existantes.

Résultats:

La plupart des programmes sondés offrent des services similaires, qui sont conformes aux principes fondamentaux de l’intervention précoce, i.e. un accès facile et rapide, un suivi intensif dont l’emphase est mise sur l’engagement du patient et la continuité des soins, ainsi qu’une gamme d’interventions biopsychosociales intégrées fondées sur des données probantes. Toutefois, des différences sont observées parmi les programmes en ce qui concerne les critères d’admission et de fin de suivi, les services offerts aux patients à ultra haut risque (UHR) de psychose, les ratios patients-clinicien, l’accessibilité des services et l’existence d’unités d’hospitalisation spécifiques. Ces éléments semblent diverger des recommandations d’expert.

Conclusions:

Bien que les programmes canadiens suivent la plupart des recommandations d’expert sur les composantes cliniques des soins, certains programmes n’ont pas implanté des éléments administratifs et organisationnels jugés essentiels. Le mentorat et le réseautage de cliniciens via des organisations telles que le Consortium canadien pour l’intervention précoce en psychose (CCIPP), ainsi que l’élaboration éventuelle d’une échelle de fidélité par le biais de recherches futures, pourraient aider les programmes à atteindre et maintenir les meilleurs standards pour les SIP. Cependant, le simple fait de présenter des guides de pratique aux cliniciens ne suffit pas à changer les pratiques; il est nécessaire que ce soit accompagné d’un financement adéquat et du soutien de la part des organisations et des décideurs.

Clinical Implications

Although most surveyed programs offer services based on core early intervention services (EIS) principles, some lack administrative and organizational elements and interventions considered essential.

Comparison with guidelines is helpful, but the development of a fidelity scale is warranted to evaluate programs and examine if fidelity is related to outcome.

Making clinical guidelines available to care providers is not sufficient for changing practices: support and engagement are required from individuals, organizations, and policy makers.

Limitations

Only urban academic EIS were surveyed, limiting generalization to rural or nonacademic programs; certain provinces were also more highly represented than others.

Although many guidelines highlight the importance of formally evaluating medication side effects (e.g., metabolic), this element and pharmacological interventions were not surveyed.

This study bears the limitations of self-reporting, including variation in data-gathering capacity among programs and possibly underreporting of some problematic aspects (desirability bias).

The past 2 decades have seen a substantial growth in the development of specialized early intervention services (EIS) for psychosis. Early psychosis could be defined as the first 2 to 5 years following the onset of a psychotic disorder. Although EIS are now widely recognized as more effective than routine care for treatment of early psychosis,1–4 they are not universally available in Canada. To aid in standardization of service delivery, some countries have developed national guidelines or standards for EIS.5–8 However, in many countries, EIS have been developed in the absence of official standards of care and/or government policy. Canada has yet to develop a national policy, guidelines, or standards for EIS, although provincial guidelines do exist in some regions.9–12

Expert consensus13,14 has identified essential components of EIS—namely, community interventions to increase detection of new cases; easy and rapid access to services; integrated biopsychosocial care plan, including pharmacotherapy; individual, group, and family psychosocial interventions; educational and vocational plans; treatment of comorbidities such as addictions; multidisciplinary teams including a psychiatrist; and formal processes for evaluation of quality of services and patient outcome.14

Little is known about the implementation of such components in many programs. In fact, surveys in Canada,67 Australia,15 and Italy16 have shown that the implementation of EIS is often slow and heterogeneous; moreover, organizational components of programs are seldom studied.13 Interestingly, it has been suggested that clinical mentors and funding might be more influential than research evidence in the implementation of such services.17

There are few published reports describing and comparing the services of early intervention (EI) programs across an entire country or region. Although a number of EIS have been developed in Canada, the extent of variability in services delivered and adherence to existing standards remain largely unknown.

The Canadian Consortium for Early Intervention in Psychosis (CCEIP), established in 2012, has among its main objectives the establishment of national standards for service delivery in early phase psychosis. As a first step towards meeting this objective, the present study was designed to obtain a comprehensive understanding of current service delivery in Canada. Our aim was to obtain a detailed description of current practices in different EIS, to explore variations and similarities in services provided, and to compare these with current guidelines for EIS.

Methods

We used a cross-sectional descriptive study method. An online benchmark survey, consisting of both closed- and open-ended questions, was created with the following themes: general program characteristics, population covered, referral sources, staffing, criteria for patient admission and discharge, individual services offered, evaluation of program quality and outcomes, training, education, and research. Specific pharmacological aspects of treatment were not surveyed as we intended to concentrate mainly on service organization and content. Program directors and coordinators from 11 EIS across Canada were asked to complete the survey and the results were reviewed by an expert panel. Based on this review, a revised set of questions was sent to each program for clarification of individual items. Descriptive statistics were compiled based on the final responses. Tabulated data were circulated to all responders to ensure that the data accurately reflected the reality of their service.

An electronic database search, as well as regular Internet searching tools (e.g., Google Scholar) and manual search, was conducted to find existing Canadian and international guidelines for EIS or studies on essential EIS components. The results of our survey were compared to the recommendations reported in the literature.

Results

Program Characteristics

All 11 EIS members of the CCEIP (at the time of the survey) responded. The program characteristics are detailed in online supplementary Table S1, and patient characteristics are detailed in Table S2. Clinical guidelines from the United Kingdom (NHS,5 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE],18 Initiative to Reduce the Impact of Schizophrenia [IRIS]19), Australia,6 New Zealand,7 and Italy,20 as well as from 4 Canadian provinces (British Columbia,9 Ontario,11 New Brunswick,12 Nova Scotia10), were examined, and their main points are summarized in Table S3.

Although Québec’s Centre national d’excellence en Santé Mentale launched its EIS implementation guide proposition21 in summer 2014, it was not included in this review as it was published after the survey and therefore could not have influenced the clinical practices.

Location and funding

The surveyed programs were located in academic psychiatric hospitals (3 programs) or academic general hospitals (7 programs), and 1 program was located in a community setting, although organizationally part of a hospital. Most programs rely on hospital budget to fund their clinical activities; only 4 have designated/protected funding.

Mandate

All programs have an identified clear mandate, for early detection and intervention in psychosis. All EIS serve a designated catchment area, ranging from 120,000 to 1,300,000 (average population covered: 410,000). Altogether, programs cover an estimated total of 4,415,000 population, approximately 13% of the country’s population. Six programs offer expert opinion and clinical consultation services outside their region. All programs provide services in English, with programs in Québec offering services in both French and/or English, depending on the patients’ language and the location of the program.

Admission criteria

Experts recommend that programs have inclusive admission criteria to ensure that all patients with early psychosis receive specialized and comprehensive services. Because of the typical age of onset of illness and to prevent disruption of care or disengagement when patients enter adulthood,9 it is often recommended that programs accept patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis starting at age 125,18,19 or 13,9 up to around age 35. In surveyed programs, the lower age limit varies from 12 to 18 years (16 for 3 programs and 18 for 3 programs), and 7 programs accept patients up to age 35.

Likewise, experts recommend accepting patients with both affective and nonaffective psychosis diagnoses, in order to not withhold services from patients who would benefit from them.5 All surveyed programs provide care for patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders; 7 also provide services to patients with affective psychosis (bipolar disorder with psychotic features and psychotic depression). Moreover, all programs accept patients with comorbid personality disorders.

According to experts, patients with comorbid substance use disorder6,9,13,19 should not be excluded from EIS. None of the surveyed programs excluded patients on this basis. Patients initially diagnosed with substance-induced psychosis are often later rediagnosed as having another psychotic disorder such as such as schizophrenia spectrum disorders.23,24 Experts therefore recommend minimally an extended period of follow-up of patients with a diagnosis of substance-induced psychosis. Among surveyed EIS, 9 offer services to patients with substance-induced psychosis.

Many experts also recommend that most patients with lifelong medical comorbidities be included in EIS, with support from other health specialists when needed. When the medical condition is the pathology underlying psychosis, patients might be best treated by an expert in the field, and EIS could then have a supportive role in managing psychiatric symptoms.5,6 Nevertheless, many surveyed programs report exclusion criteria that are related to severe brain medical conditions (e.g., acquired brain injury, epilepsy, developmental disorders) because of their potential to account for psychotic symptoms (Table S1).

Some studies have suggested that interventions and pharmacological treatments for patients considered to be at ultra high risk (UHR) could delay or prevent transition to psychosis.25–29 It has also been argued that intervening with patients who might never transition to frank psychosis might carry risks.7,27,30 UHR patients have high rates of comorbid conditions and cognitive deficits,31 both of which are associated with functional disability,32 lower quality of life,33 and increased suicidality.34 Therefore, it is recommended that UHR patients be offered services, mainly monitoring and psychosocial interventions,5,6,7,9,13,14,19 to address the existing symptoms and deficits and to intervene promptly if psychosis was to develop.31 Three surveyed programs provide services to and/or engage in research with individuals who meet criteria for being at ultra high risk for psychosis,31,35 while others indicate offering follow-up on only a selective basis to this category of patients or referring them to an UHR clinic in their region if available.

Service duration and discharge criteria

Concerns have been raised about whether a duration of 2 or 3 years of intensive intervention is sufficient since most clinical benefits brought by 2 years EIS are not sustained at 5 years if specialized services are not continued.36–38 Trials are ongoing to determine whether longer durations of EIS are preferable. As of now, experts recommend durations varying between 39,11,18,19 and 5 years.10,39 All surveyed programs provide services for a period ranging from 2 to 5 years, with more than half having a duration of 2 or 3 years. In 3 clinics, patients can be discharged before the end of the program if remitted from positive symptoms or having recovered sufficiently to be treated in a primary care setting.

Continuity of care is a cornerstone of EIS, and maintaining patient engagement is considered crucial. However, about 30% of patients disengage prematurely from EIS,40 which can lead to serious consequences for clinical state and social functioning. Despite this evidence, a few of the programs surveyed will discharge patients because of patient refusal of treatment or noncompliance to treatment (both pharmacological and nonpharmacological). This might be explained by administrative constraints forcing closure of files in those cases, leading to premature termination of care.1 Most programs use community treatment orders when necessary.

Overall, 25% of patients from the surveyed programs are discharged to a family physician or an equivalent primary health care setting, 15% to a community mental health clinic, 40% to a psychotic disorder service, and 20% to other resources (e.g., Canadian Mental Health Association clinics, assertive community treatment [ACT], and specialized services such as a dual-disorder clinic [psychosis and substance misuse]).

Description of services

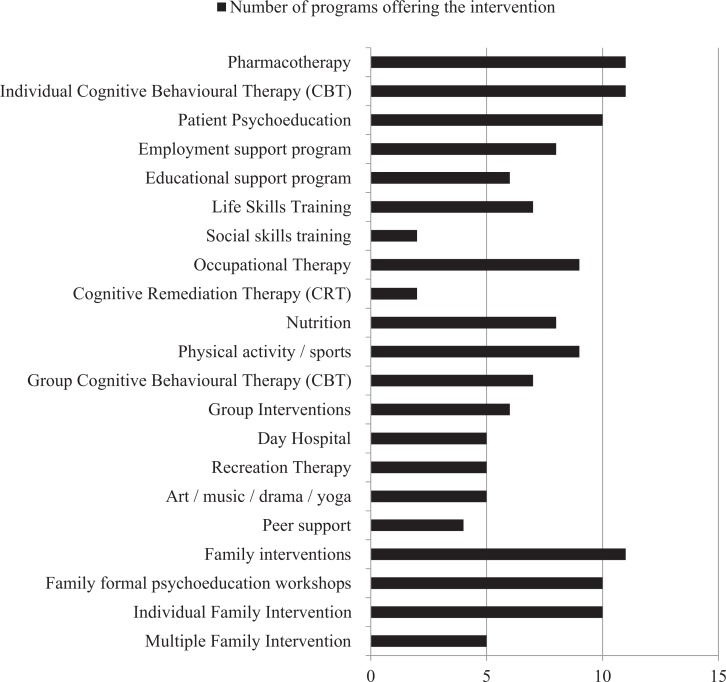

Most programs offer a range of integrated treatments, including psychopharmacology and evidence-based psychosocial interventions, individually or in group format. These include family interventions, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), and outreach interventions (e.g., home and community visits, liaising with community and vocational agencies, schools, and housing facilities), which have been shown to improve clinical outcome1,2,3,4 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interventions provided within the 11 surveyed Canadian academic early intervention programs.

Clinicians (e.g., case managers) of all programs spend on average about a third of their time in community outreach interventions. Moreover, most EIS (n = 9) report formal agreements with external services (addiction, housing, and employment services).

Early psychosis patients often describe hospitalizations as highly distressing, sometimes traumatic, experiences.41–43 Such experiences could have a negative impact on patients’ engagement and prevent them from seeking psychiatric help in the future.42 A specifically designed inpatient unit is likely to be the most appropriate setting for patients requiring hospitalization.6 Most programs (n = 8) have specifically allocated hospital beds, but not necessarily a custom-designed unit for EIS. These inpatient beds are managed by the EIS psychiatrists, either in a general psychiatry ward or in a psychosis unit.

Staff

Most experts recommend a case management model of care, where one clinician (with varying professional background such as occupational therapist, social worker, nurse) has a central role in the treatment of an individual patient, often combining delivery of direct clinical services, coordinating care and services, and, when necessary, brokering access to other services.44,45 Nine of the EIS surveyed have a case management model. To achieve the intensity of care needed for effective treatment, it is recommended that caseloads be kept low (15 to 1).6,7,9,19,45 However, patient to clinician ratios vary widely among surveyed clinics, from 19:1 to 50:1, with 7 programs having ratios between 20:1 and 30:1.

Two EIS provide multidisciplinary care with a consultation model (i.e., where various mental health professionals provide services to one individual patient, based on their specific competencies to meet his or her needs). One of those clinics provides case management services through an ACT team specifically serving early psychosis patients presenting with more severe pathologies, where caseloads are kept at 8 to 1.

Program accessibility

All reviewed recommendations emphasize ease of access to programs, in order to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), which has been shown to negatively influence treatment outcome.46–49 It has been shown that aspects of the health system can lead to treatment delay.50 An open referral policy with rapid assessment of new patients is generally recommended,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,19,40,51 along with community interventions and training of referral sources to increase detection of possible cases.52

Nine of 11 surveyed programs operate an open referral policy accepting self- or community referrals (e.g., family, friends, community organisations, schools, community mental health agencies). However, in all programs, a significant proportion of referrals comes from psychiatrists, family physicians, hospital inpatient units, and, especially, hospital emergency services. Ten programs have established standards for time to screening, assessment, or entry. For 6 programs, initial contact with a professional is expected to occur within 72 hours; for 8 programs, face-to-face full assessment is expected to be provided within 1 to 2 weeks; for 9 programs, maximum time to entry into the program is expected to be between 1 week and 2 months. Seven of the 11 programs report engaging in interventions to reduce delay in treatment, mostly through public education or direct education of sources of referral.

Clinical/research evaluation tools

All programs conduct an initial screening assessment to rule out nonpsychotic illness and to determine if the referred patient meets admission criteria. Nine programs have a formal protocol for comprehensive patient assessment after referral; 5 programs use standardized diagnostic tools (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV [SCID]), and 3 programs administer the SCID more than once during follow-up.

Nine programs make regular use of standardized tools to monitor patients’ symptoms longitudinally (e.g., Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS],53 Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms [SANS],54 Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms [SAPS],55 Calgary Depression Scale [CDS]56) and functioning (e.g., Global Assessment of Functioning [GAF],57 Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale [SOFAS],58 Quality of Life [QOL]23). The interval of administration of such scales ranges from every few months to every 3 years.

Four programs use various assessment tools for diagnosis and monitoring of substance misuse (e.g., Drug Abuse Screening Test [DAST],59 Alcohol Use Scale [AUS],60 Drug Use Scale [DUS],61 Timeline Follow-back [TLFB],61 Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test [AUDIT]62).

Estimation of rates of referral, admissions, and patient characteristics

The average number of referrals and admissions to programs is 27.8 and 18.8, respectively, per 100,000 population covered. The average age of patients at admission is 23.4 years, 48.3% are studying or working, 58.5% are living with their parents, and 34.8% are living independently. The proportion of first-generation immigrants varies between programs, ranging from 10% and 42%, while 10% to 40% of patients at surveyed clinics are so-called visible minorities (see Table S2). Overall, at the time of referral, programs reported that 65% of patients have been using antipsychotic medication for less than 1 month, 23% for 1 to 3 months, 8% for 3 to 6 months, and 4% for over 6 months.

Program evaluation

Formal processes for evaluation of program quality and individual patients’ outcome are recognized as fundamental components of any health care service. Most programs engage in such procedures, which monitor whether program objectives are being met and help maintain consistent quality in service delivery.9 Eight programs have a formal process for regular evaluation of patient and treatment outcome, and all are involved in evaluation of quality assurance. Moreover, in their administrative structure, 3 programs have an advisory committee (of those 3 programs, one has an advisory committee that includes patients, families, and community representatives and also has an advocacy role).

Education and research

As recommended by experts, 8 programs engage in organized continuing education (e.g., journal clubs and lectures) to maintain the competence of the program’s staff.6,7,9,12,13 All programs provide training and education to psychiatry residents, and 4 provide advanced fellowship training to postgraduate clinicians. Other programs provide training and education to medical (n = 10), social work (n = 10), occupational therapy (n = 6), and nursing students (n = 11); psychology interns (n = 6); and graduate students (n = 5). All but one program conduct some research, which is considered necessary to improve knowledge in the field6,9,12 and promote knowledge transfer. Nine EIS have produced peer-reviewed publications in the past 5 years (ranging from 8-88 publications); all programs report some collaboration with other facilities on research projects. Clinical research is conducted on various topics such as early psychosis outcome, epidemiology, psychopharmacology, neurobiology, and psychosocial and service-related research.

Discussion

In general, surveyed programs offer good services, based on the core EI principles such as easy access to services, intervening early, offering intensive follow-up through case management, providing a range of evidence-based psychosocial interventions, and promoting patients’ engagement and continuity of care (e.g., outreach, youth-friendly environment).

The availability of national and international standards of care may contribute to our findings. Other factors are also likely to influence adoption of good practices, such as peer and regional influence.17 Indeed, some programs regularly meet either for continuing education or to share administrative and service organization concerns (e.g., Association québécoise des programmes pour premiers épisodes psychotiques [AQPPEP], Early Psychosis Intervention Services in Ontario [EPION]), which could encourage clinicians in adopting similar practices to other clinicians in their network.

However, important elements are still lacking from some programs. Interestingly, even programs located in provinces having adopted standards of care were in some cases found to deviate from their own provincial guidelines on aspects such as admission criteria, services for UHR patients, length of service provision, and patient to clinician ratios. Indeed, studies in psychiatry and general medicine indicate that publishing data on effective interventions or even synthesizing research evidence into treatment algorithms or clinical guidelines is not sufficient for large-scale implementation of evidence-based practices.16,63 The challenge seems to be even greater when it comes to implementing complex psychosocial interventions.63 Nationally, surveys conducted in 2004 and 2008 in British Columbia revealed that, despite the adoption of guidelines64 in 2002, provision of services was heterogeneous. Some of the British Columbia EIS were still lacking elements considered fundamental, and EIS provided within traditional mental health services were even less likely to meet standards.9,67 Similar findings were revealed in studies from Italy, Australia, and the United States.15,16,63 Explanations may include insufficient funding of programs,16 difficulties in collaboration among services caring for patients, rapid staff turnover,63,65 and reluctance to change established practices.17 However, a study showed that establishing an audit process encourages documentation of clinical interventions and adherence to implemented guidelines in EIS.66 The development of fidelity scales has also been shown to improve patient outcome in supported employment services and assertive community treatment, although less consistently for the latter.63 In recent years, the issue of implementation of evidence-based practices has been more pressing, and the growing literature calls for deep changes, including adequate funding for the mental health system, more stability in the workforce (both clinical and administrative), use of information technology for staff training, and mentoring65 and monitoring of interventions and outcomes through electronic medical records.63,65

Conclusion

The portrait of the Canadian situation in urban academic programs reveals good service provision for early psychosis patients in those settings. However, Canadian programs, as elsewhere in the world, are faced with local challenges. Health care is administered by provinces, and service provision is therefore subjected to regional priorities and resources, reflecting not only financial limitations but also the diversity of populations served and settings. Some degree of variation observed among programs may reflect adaptation of EIS to the needs of the population served. However, in some cases, fundamental elements of EI are lacking. Programs located in provinces having adopted standards of care follow most of those recommendations. This situation calls for a clearer definition of what Canadian EIS should consist of: this study is the first step required in the establishment of Canadian standards of care for early intervention in psychosis.

Further research is warranted to characterize rural and nonacademic EI programs, determine models that are likely to better fit their needs, and investigate obstacles to the application of best practices in Canada. The development of guidelines specific to the Canadian situation, continued mentoring and networking of clinicians through organizations such as the Canadian Consortium for Early Intervention in psychosis, and the development of a fidelity scale through further research could possibly help programs attain and maintain the best standards of early intervention. However, simply making clinical guidelines available to care providers is unlikely to be sufficient for changing practices; this will need to be accompanied by adequate funding and support from organizations and policy makers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors have submitted this article on behalf of the Canadian Consortium for Early Intervention in Psychosis. The Canadian Consortium for Early Intervention in Psychosis received funding for conducting this survey from the following companies: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Otsuka Canada Pharmaceutical, and Lundbeck Canada. The authors did not receive any individual funding. We wish to acknowledge the support provided by Myelin and Associates in the final formatting of this manuscript for submission.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: The online supplementary tables are available at http://cpa.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- 1. Petersen L, Thorup A, Øqhlenschlaeger J, et al. Predictors of remission and recovery in a first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder sample: 2-year follow-up of the OPUS trial. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53(10):660–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, et al. Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness: the OPUS trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):762–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, et al. A randomised multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. BMJ. 2005;331(7517):602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Craig TK, Garety P, Power P, et al. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. BMJ. 2004;329(7474):1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Institute for Mental Health in England (NIMHE). Early intervention (EI) acceptance criteria guidance. England: NIMHE National Early Intervention Programme; 2008. [accessed 2016 February 13]. Available from: http://www.iris-initiative.org.uk/silo/files/eligibility-criteria-for-accessing-eip-service-.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6. EPPIC. Australian clinical guidelines for early psychosis. 2nd ed Melbourne, Australia: Orygen Youth Health Research Centre; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Disley B. Early intervention in psychosis guidance note. Mental Health [Internet]. 1999. [cited 2014 December 5];2. Available from: http://www.hdc.org.nz/media/200643/early%20intervention%20in%20psychosis%20-%20guidance%20note%20march%2099.pdf

- 8. De Masi S, Sampaolo L, Mele A, et al. The Italian guidelines for early intervention in schizophrenia: development and conclusions. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2008;2(4):291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ehmann T, Hanson L, Yager J, et al. Standards and guidelines for early psychosis intervention (EPI) programs. British Columbia, Canada: Services Ministry of Health; 2010. [accessed 2016 February 13]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2010/BC_EPI_Standards_Guidelines.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nova Scotia Department of Health. Nova Scotia provincial service standards for early psychosis. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Nova Scotia Department of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ontario Working Group. Program policy framework for early intervention in psychosis. Ontario Working Group; 2004 [accessed 2016 February 13]. Available from: http://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/psychosis.pdf

- 12. Early Psychosis Services N.B. Administrative guidelines. Fredericton, New Brunswick: Addiction, Mental Health and Primary Health Care Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Addington DE, McKenzie E, Norman R, et al. Essential evidence-based components of first-episode psychosis services. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(5):452–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bertolote J, McGorry P. Early intervention and recovery for young people with early psychosis: consensus statement. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2005;48:s116–s119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Catts SV, Evans RW, O’Toole BI, et al. Is a national framework for implementing early psychosis services necessary? Results of a survey of Australian mental health service directors. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghio L, Natta W, Peruzzo L, et al. Process of implementation and development of early psychosis clinical services in Italy: a survey. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012;6(3):341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cheng C, Dewa CS, Goering P. Matryoshka Project: lessons learned about early intervention in psychosis programme development. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5(1):64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people—recognition and management. NICE clinical guideline 1552013 Manchester, England: NICE; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Initiative to Reduce Impact of Schizophrenia (IRIS). IRIS guidelines update. IRIS; 2012 [accessed 2016 February 13]. Available from: http://www.iris-initiative.org.uk/silo/files/iris-guidelines-update--september-2012.pdf/

- 20. Early intervention in schizophrenia—guidelines. Milan, Italy: Italian National Guidelines System (SNLG); 2009. [accessed 2016 February 13]. Available from: http://www.snlg-iss.it/cms/files/LG_en_schizophrenia.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21. Proposition de guide à l’implantation des équipes de premier épisode psychotique. Montréal: Centre national d’excellence en santé mentale, Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT., Jr The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arendt M, Mortensen PB, Rosenberg R, et al. Familial predisposition for psychiatric disorder: comparison of subjects treated for cannabis-induced psychosis and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(11):1269–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Niemi-Pynttari JA, Sund R, Putkonen H, et al. Substance-induced psychoses converting into schizophrenia: a register-based study of 18,478 Finnish inpatient cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):e94–e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nordentoft M, Thorup A, Petersen L, et al. Transition rates from schizotypal disorder to psychotic disorder for first-contact patients included in the OPUS trial: a randomized clinical trial of integrated treatment and standard treatment. Schizophr Res. 2006;83(1):29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marshall M, Rathbone J. Early intervention for psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD004718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):790–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morrison AP, French P, Walford L, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, et al. The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(1):107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Simon AE, Gradel M, Cattapan-Ludewig K, et al. Cognitive functioning in at-risk mental states for psychosis and 2-year clinical outcome. Schizophr Res. 2012;142(1-3):108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Niendam TA, Bearden CE, Johnson JK, et al. Neurocognitive performance and functional disability in the psychosis prodrome. Schizophr Res. 2006;84(1):100–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bechdolf A, Pukrop R, Kohn D, et al. Subjective quality of life in subjects at risk for a first episode of psychosis: a comparison with first episode schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(1):137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hutton P, Bowe S, Parker S, Ford S. Prevalence of suicide risk factors in people at ultra-high risk of developing psychosis: a service audit. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5(4):375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):353–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gafoor R, Nitsch D, Craig T, et al. Does early intervention (EI) in schizophrenia improve long term outcome? Results from 5 year follow-up study (South London Interventions in First Episode psychosis—LIFE). Early Interv Psychiatry. 2008;2(Suppl 1):A6. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, et al. Course of illness in a sample of 265 patients with first-episode psychosis—five-year follow-up of the Danish OPUS trial. Schizophr Res. 2009;107(2-3):173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nordentoft M, Rasmussen JO, Melau M, et al. How successful are first episode programs? A review of the evidence for specialized assertive early intervention. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(3):167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. International Early Psychosis Association Writing Group. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatr Suppl. 2005;187(48):s120–s124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Doyle R, Turner N, Fanning F, et al. First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(5):603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berry K, Ford S, Jellicoe-Jones L, et al. PTSD symptoms associated with the experiences of psychosis and hospitalisation: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(4):526–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tarrier N, Khan S, Cater J, Picken A. The subjective consequences of suffering a first episode psychosis: trauma and suicide behaviour. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(1):29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McGorry PD, Chanen A, McCarthy E, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder following recent-onset psychosis: an unrecognized postpsychotic syndrome. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179(5):253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fowler D, Hodgekins J, Howells L, et al. Can targeted early intervention improve functional recovery in psychosis? A historical control evaluation of the effectiveness of different models of early intervention service provision in Norfolk 1998-2007. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3(4):282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dieterich M, Irving CB, Park B, et al. Intensive case management for severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD007906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Norman RM, Malla AK. Duration of untreated psychosis: a critical examination of the concept and its importance. Psychol Med. 2001;31(3):381–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Harris MG, Henry LP, Harrigan SM, et al. The relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome: an eight-year prospective study. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(1):85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, et al. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(9):975–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Malla AM, Norman RM. Treating psychosis: is there more to early intervention than intervening early? Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(7):645–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Scholten DJ, Malla AK, Norman RM, et al. Removing barriers to treatment of first-episode psychotic disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(8):561–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Larsen TK, Joa I, Langeveld J, et al. Optimizing health-care systems to promote early detection of psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3(Suppl 1):S13–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Andreasen N. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Andreasen N. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3(4):247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hall RC. Global assessment of functioning: a modified scale. Psychosomatics. 1995;36(3):267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(9):1148–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7(4):363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Moller T, Linaker OM. Using brief self-reports and clinician scales to screen for substance use disorders in psychotic patients. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(2):130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back. A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: psychosocial and biological methods Totowa (NJ: ): Humana Press; 1992. p. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Babor TF, Biddle-Higgins JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary care. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Drake RE, Bond GR, Essock SM. Implementing evidence-based practices for people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(4):704–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ehmann T, Hanson L. Early psychosis: a care guide. Mental Health Evaluation and Community Consultation Unit, University of British Columbia; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Woltmann EM, Whitley R, McHugo GJ, et al. The role of staff turnover in the implementation of evidence-based practices in mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(7):732–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Petrakis M, Hamilton B, Penno S, et al. Fidelity to clinical guidelines using a care pathway in the treatment of first episode psychosis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(4):722–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ehmann T. A Quiet Evolution: Early Psychosis Services in British Columbia. BC Schizophrenia Society; 2004 [Cited 2016 February 13]. Available from: http://www.bcss.org/documents/pdf/EarlyPsychosisStudy.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.