Abstract

Legionella pneumophila, the causative agent of Legionnaires disease, has a biphasic life cycle with a switch from a replicative to a transmissive phenotype. During the replicative phase, the bacteria grow within host cells in Legionella-containing vacuoles. During the transmissive phenotype and the postexponential (PE) growth phase, the pathogens express virulence factors, become flagellated, and leave the Legionella-containing vacuoles. Using 13C labeling experiments, we now show that, under in vitro conditions, serine is mainly metabolized during the replicative phase for the biosynthesis of some amino acids and for energy generation. During the PE phase, these carbon fluxes are reduced, and glucose also serves as an additional carbon substrate to feed the biosynthesis of poly-3-hydroxybuyrate (PHB), an essential carbon source for transmissive L. pneumophila. Whole-cell FTIR analysis and comparative isotopologue profiling further reveal that a putative 3-ketothiolase (Lpp1788) and a PHB polymerase (Lpp0650), but not enzymes of the crotonyl-CoA pathway (Lpp0931–0933) are involved in PHB metabolism during the PE phase. However, the data also reflect that additional bypassing reactions for PHB synthesis exist in agreement with in vivo competition assays using Acanthamoeba castellannii or human macrophage-like U937 cells as host cells. The data suggest that substrate usage and PHB metabolism are coordinated during the life cycle of the pathogen.

Keywords: biosynthesis, isotopic tracer, lipid metabolism, metabolism, pathogenesis, Legionella, polyhydroxybutyrate

Introduction

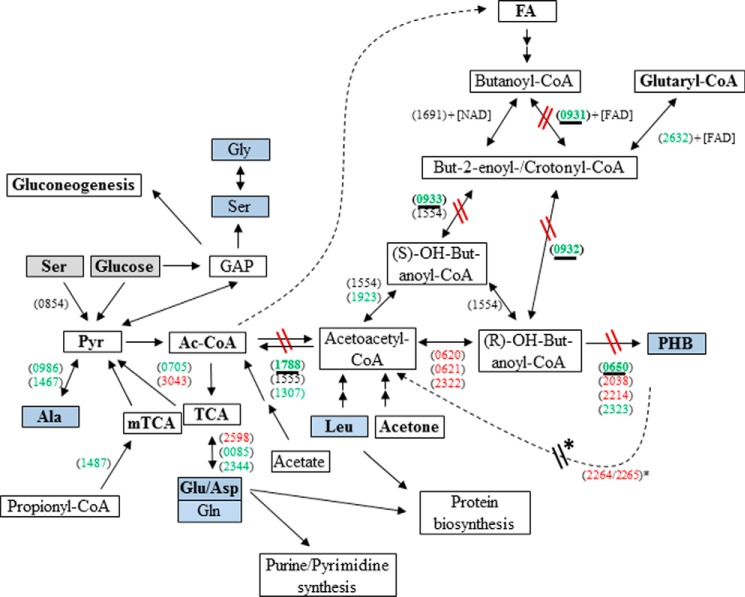

In fresh water habitats, Legionella pneumophila replicates in protozoa, mainly amoebae, but the Gram-negative bacteria can also be found within biofilms. Accidentally, L. pneumophila can be transmitted by contaminated aerosols to humans where it replicates within alveolar macrophages, leading to an atypical pneumonia (Legionnaires disease). Intracellularly, L. pneumophila replicates in vacuoles (Legionella-containing vacuoles). When nutrients become limiting, L. pneumophila differentiates into the mature intracellular form. This phase corresponds to the transmissive phase in which L. pneumophila becomes flagellated, expresses its virulence factors, and seems to be metabolically dormant (1–4). This biphasic life cycle is also observed during growth in liquid medium, and therefore, in vitro experiments are considered as valid models to analyze the specific features encountered during both phases (3). In the transmissive phase of L. pneumophila, high amounts of cytoplasmic granules of poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB)4 are observed in L. pneumophila. Generally, this polymer is known as an important energy and carbon storage for some bacteria (1, 5–8). Indeed, PHB is also essential for the survival of L. pneumophila in the environment where it is catabolized during the viable but non-culturable state of L. pneumophila (7–10). However, less is known about the temporary amounts of PHB and the dynamics of PHB metabolism during the life cycle of L. pneumophila (1, 7, 10–12). PHB seems to be synthesized from acetyl-CoA (Ac-CoA) when the NAD(P)H concentration in the bacterium increases, the activity of the TCA is reduced, and the genes encoding enzymes of PHB formation are induced (5, 7, 13). In the first step of PHB biosynthesis, the enzyme 3-ketothiolase catalyzes the reaction of Ac-CoA to acetoacetyl-CoA. Acetoacetyl-CoA is then reduced to (R)-3-hydroxybutanoyl-CoA by a reductase. In the last step, (R)-3-hydroxybutanoyl-CoA is polymerized into PHB (see Fig. 1). In L. pneumophila Paris, three putative 3-ketothiolases (Lpp1788, Lpp1555, and Lpp1307), three putative acetoacetyl-CoA reductases (Lpp0620, Lpp0621, and Lpp2322), and four putative PHB synthases (Lpp0650, Lpp2038, Lpp2214, and Lpp2323) can be assigned on the basis of sequence homologies (13, 14). However, a functional assignment of these proteins is missing. Even the carbon substrates providing the Ac-CoA precursors are still obscure. Using radiotracers, it was shown earlier that carbon from Leu and acetone enters the lipid fraction of L. pneumophila also containing PHB (15) (see also Fig. 1). Alternatively, carbon flux into PHB was suggested to start from fatty acid degradation (involving Lpp0932) (16–18). However, in earlier 13C experiments using steady-state labeling until the postexponential growth phase of L. pneumophila, PHB acquired label from [U-13C3]serine and to a minor extent from [U-13C6]glucose via [13C2]Ac-CoA (19).

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the metabolic pathways in L. pneumophila Paris relevant for PHB formation and degradation. Key reactions investigated in this study are highlighted by underlined gene numbers. 13C-Labeled substrates used in this study are indicated by gray boxes. Analyzed metabolites are indicated by blue boxes. Gene numbers (lpp) are indicated in parentheses, genes given in green are more highly expressed in the exponential phase, whereas genes given in red are induced in the transmissive (PE) phase (13). Reactions affected in the mutant strains are indicated. FA, fatty acids. * refers to Ref. 48. The genes indicated here are generally present in all known genomes of Legionella strains. GAP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; mTCA, methylcitrate cycle.

Mainly on the basis of genome sequencing and studies under in vitro conditions, the core metabolic capabilities of L. pneumophila appear to be known (20). It is now established knowledge that amino acids, e.g. serine, are main carbon and energy sources for L. pneumophila during growth in medium (15, 21–26). Using 13C isotopologue profiling with L. pneumophila growing under in vitro conditions until the late exponential phase, serine was efficiently converted into pyruvate and further into Ac-CoA, which can be shuffled into the TCA (19) (see Fig. 1). Amino acids also play an important role as nutrients during growth within host cells (14, 20, 27–29).

It has been repeatedly reported that glucose is not a major carbon substrate of L. pneumophila (16, 30, 31), although genome analyses revealed the presence of the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway and the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway (16, 20, 32). More recently, 13C labeling experiments under in vitro conditions demonstrated that exogenous glucose can indeed be utilized through the ED pathway, finally providing pyruvate, oxaloacetate, and α-ketoglutarate as precursors for some amino acids and acetyl-CoA for PHB biosynthesis (19) (Fig. 1). It was also reported that the ED pathway is necessary during the intracellular life cycle of L. pneumophila (33). Indeed, host cell glycogen could be degraded to glucose by the action of the bacterial glucoamylase GamA (19, 34). Further supporting the role of glucose as a nutrient for intracellular L. pneumophila, glucose uptake was found to be increased during the late phases of growth (33), and Legionella species-specific differences in their usages of glucose and serine as carbon substrates were suggested recently (35, 36). However, the differential transfer of substrates during the different growth phases of L. pneumophila has not yet been directly shown. We have now analyzed by growth phase-dependent whole-cell Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and isotopologue profiling the relative amounts of PHB, the pathways in PHB formation and degradation, and the underlying metabolic fluxes starting from different substrates during the various growth phases of the L. pneumophila strain Paris.

Experimental Procedures

Strains, Growth Conditions, Media, and Buffers

L. pneumophila Paris wild type was used in this study (32). The following isogenic mutant strains were used: Δketo (lpp1788; acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, β-ketothiolase) (14), Δzwf (lpp0483; glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase) (19), Δgam (lpp0489; glucoamylase) (34), Δlpp0931–33, Δketo/Δlpp0931–33, and Δlpp0650 mutant strains (this work; see below). Escherichia coli DH5α, serving as host for amplification of recombinant plasmid DNA, was grown in lysogeny broth (LB) or on LB agar (37, 38).

Acanthamoeba castellanii ATCC 30010 was cultured in PYG 712 medium (2% proteose peptone, 0.1% yeast extract, 0.1 m glucose, 4 mm MgSO4 × 7 H2O, 0.4 m CaCl2 × 2 H2O, 0.1% sodium citrate dihydrate, 0.05 mm Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 × 6 H2O, 2.5 mm NaH2PO4, and 2.5 mm K2HPO4) at 20 °C. The Acanthamoeba buffer was PYG 712 medium without peptone, yeast extract, and glucose. The U937 human macrophage-like cell line ATCC CRL-1593.2 was cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium + 10% FCS (PAA/GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany) at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

L. pneumophila was grown in ACES-buffered yeast extract (AYE) broth consisting of 10 g of ACES, 10 g of yeast extract, 0.4 g of l-Cys, and 0.25 g of ferric pyrophosphate/liter (adjusted to pH 6.8 with 3 m KOH and sterile filtrated) at 37 °C with agitation at 250 rpm or on buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar for 3 days at 37 °C. For cultivation of L. pneumophila on agar plates, kanamycin was used at a final concentration of 12.5 μg/ml. Bacterial growth in AYE medium was monitored by determining the absorbance at 600 nm (A600) with a Thermo Scientific GENESYS 10 Bio spectrophotometer (VWR, Darmstadt, Germany). When appropriate, media were supplemented with antibiotics to final concentrations of kanamycin of 8 or 40 μg/ml for L. pneumophila or E. coli, respectively, and ampicillin at 100 μg/ml for E. coli.

Intracellular Replication (Infection) Assay in A. castellanii and U937 Cells

The intracellular multiplication assays were carried out at a growth temperature of 37 °C as described earlier (19, 39).

DNA Techniques and Sequence Analysis

Genomic and plasmid DNAs were prepared according to standard protocols and the manufacturer's instructions (40). PCR was carried out using a TRIO-Thermoblock (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany) and Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Foreign DNA was introduced into E. coli by electroporation with a gene pulser (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's specifications at 1.7 kV, 100 ohms, and 25 microfarads. Plasmid DNA was sequenced with infrared, dye-labeled primers using an automated DNA sequencer (LI-COR-DNA 4000, MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). Primers were obtained from Eurofins MWG Operon (Ebersberg, Germany). Restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs (Frankfurt am Main, Germany).

Gene Cloning and Construction of L. pneumophila Paris Mutants

The knock-out mutants of genes Δlpp0931–33 and Δketo/Δlpp0931–33 were constructed as described before (13). In brief, lpp0931–33 was inactivated by insertion of a gentamicin (GmR_U and GmR_R) resistance cassette into the chromosomal gene. The chromosomal region containing the respective flanking regions were PCR-amplified (primers 0931-1F and -2R), and the product was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), resulting in pVH11. On these templates, an inverse PCR was performed introducing an XbaI restriction site. They were religated and XbaI-digested (0931-3R2 and -4F; pVH12). A gentamicin cassette with XbaI restriction sites was cloned into pVH12, resulting in pVH13. For chromosomal recombination, the construct was amplified by PCR. Natural transformation of L. pneumophila Paris was done as described before with modification (14, 41). The Δketo/Δlpp0931–33 double mutant was constructed by using the Δketo strain as the acceptor strain for natural transformation using the PCR product of the lpp0931–33-GmR cassette construct (see above). Selection for double mutants was done by screening on agar plates containing kanamycin and gentamicin. Three independent Δ mutant strains were generated for each gene and confirmed by PCR analysis (data not shown).

The knock-out mutant of gene Δlpp0650 was constructed using the In-Fusion Cloning kit (Takara Clontech) according to the manufacturers' instructions. To generate the construct for natural transformation, regions of 900 bp flanking the gene lpp0650 and a kanamycin cassette were amplified by PCR. The amplification of the flanking regions (primers iLpp_0650_1U/2R and iLpp_0650_5U/6R) was done with chromosomal DNA from L. pneumophila Paris wild type (WT), and for the kanamycin cassette, pChA12 was the target (primers iLpp_0650_3U/4R). The primers were constructed with an overlap according to the instructions of the In-Fusion manual. The cloning enhancer-treated fragments were fused with the open vector pGEM-T Easy (Promega) and transformed into Stellar competent cells (Takara Clontech). Afterward, the cells were plated on LB kanamycin plates for selection. A PCR amplification confirmed colonies carrying plasmids with the flanking regions surrounding the kanamycin cassette in the vector pGEM-T Easy (control primers iLpp_650T1U/6R). The plasmid pES0650_18 was confirmed by sequencing and used for the amplification of the kanamycin cassette with the flanking regions (primers M13U/R). The amplified and purified PCR product was used for two independent natural transformations of L. pneumophila Paris WT as described above. The successful generation of the L. pneumophila Paris Δlpp0650 mutants was confirmed via PCR (primers Lpp_0650_Mut1U/2R and Lpp_0650_Wt_1U/2R). Two independent mutants were generated. For more details, see Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

Underlined nucleotides indicate the XbaI restriction site.

| Name | Tm | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| °C | |||

| 0931-1F | GCGAACATTAGGCTTGTCAATA | This work | |

| 0931-2R | GAGATTCAATCATTTTATTGCTCCACT | This work | |

| 0931-3R2 | CATTTCTAGAAATGCCAAATGTTCATC | This work | |

| 0931-4F | GCTTGCTGTCATAAGGAAGTATC | This work | |

| iLpp_0650_1U | CCGCGGGAATTCGATATCCTTTTAGCCACGATTTACTCCACTT | This work | |

| iLpp_0650_2R | TAGAAGCTGACATTCTAGCTCCTGAAAGCAAATAATCGAA | This work | |

| iLpp_0650_5U | TAGACACGATGGCCGTGGATGCCCCAGGGAGTTATGTACT | This work | |

| iLpp_0650_6R | GAATTCACTAGTGATATCAGCCCTTATTTTAGCCTTTGTTGTC | This work | |

| iLpp_0650_3U | TGCTTTCAGGAGCTAGAATGTCAGCTTCTAGACTATCTGG | This work | |

| iLpp_0650_4R | TCCCTGGGGCATCCACGGCCATCGTGTCTAGACACTCCTG | This work | |

| iLpp_0650T1U | CTTTTAGCCACGATTTACTCCACTT | This work | |

| iLpp_0650T6R | AGCCCTTATTTTAGCCTTTGTTGTC | This work | |

| Lpp_0650_Mut_1U | TCAGGTTCGCCTTTTATTGC | This work | |

| Lpp_0650_Mut2R | AATTCCTGTCCTGCCTTCAG | This work | |

| Lpp_0650_Wt_1U | CTTTCATCGCTGGTCAGTCA | This work | |

| Lpp_0650_Wt_2R | ATGAACCGGAGTGTTCCTTG | This work | |

| M13R | 54.5 | GGAAACAGCTATGACCATG | 51 |

| M13U | 52.8 | GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT | 51 |

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Immunoblotting

Flagellin detection was carried out by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. SDS-PAGE was performed as described previously (42). Equal amounts of Legionella grown in AYE broth to early exponential (EE), late exponential (LE), postexponential (PE), and stationary (S) phase were boiled for 10 min in Laemmli buffer and loaded onto a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Western blotting was carried out using polyclonal anti-FlaA antiserum diluted in 1% milk and TBS (1:1,000) (43). A horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody was used as secondary antibody (1:1,000). FlaA was visualized by incubation of the blot with 50 ml of color reaction solution (47 ml of TBS, 3 ml of 4-chloro-1-naphthol, and 80 μl of H2O2), and the reaction was stopped with distilled water. Data were obtained from at least two independent experiments.

Isotopologue Profiling of L. pneumophila Wild Type and Δketo in Medium Containing [U-13C3]Serine or [U-13C6]Glucose

The cultivation of all strains and the 13C labeling experiments were performed according to Eylert et al. (19) with the exception of using different time points for tracer addition and harvest of bacterial cells (Fig. 2A). Briefly, 1 ml of an overnight culture of the strains was added to 250 ml of AYE medium supplemented with 2 g/liter [U-13C6]glucose or 0.25 g/liter [U-13C3]serine, respectively. Incubation was conducted at 37 °C and 220 rpm. The labeling experiments were performed from A600 = 0.1 (addition of the tracer) to A600 = 1.0 (EE phase; harvest), from A600 = 1.0 (addition of the tracer) to 1.5 (LE phase; harvest), from A600 = 1.5 (addition of the tracer) to 1.9 (PE phase; harvest), or from A600 = 1.9 (addition of the tracer) plus an additional 17 h of growth (S phase; harvest), respectively. Growth was stopped by addition of 10 mm sodium azide. Bacteria were pelleted at 5,500 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. The pellets were washed twice with 200 ml of water and once again with 2 ml of water. The supernatants were discarded. Finally, the bacterial pellets were autoclaved at 120 °C for 20 min.

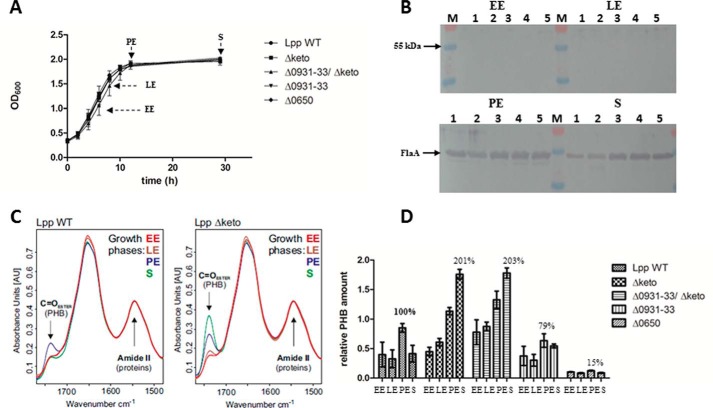

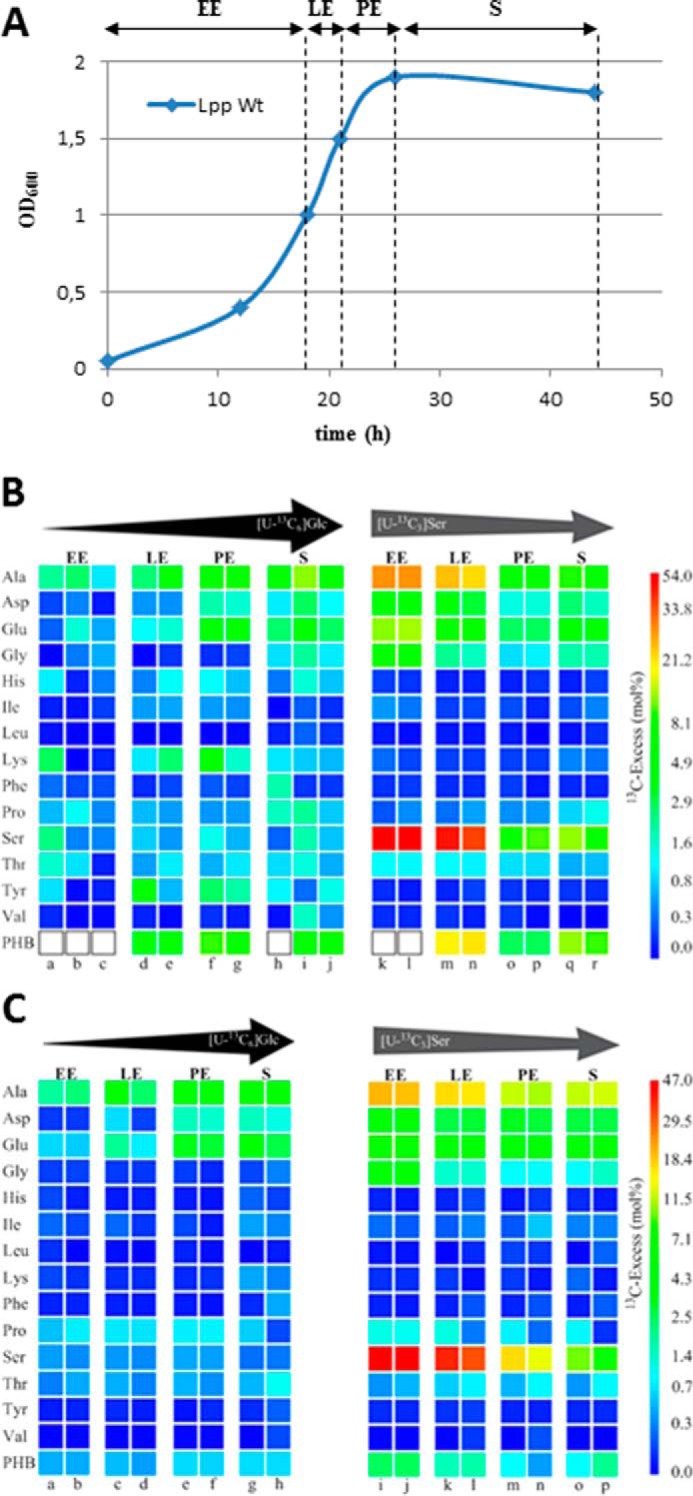

FIGURE 2.

Growth-dependent incorporation of glucose or serine into L. pneumophila grown in liquid culture. A, schematic growth curve of L. pneumophila in AYE medium at 37 °C for the indicated periods of 13C labeling (EE, LE, PE, and S). B, 13C enrichments of amino acids and PHB of L. pneumophila Paris WT grown in AYE medium at 37 °C during various growth phases (EE, LE, PE, and S) using [U-13C6]glucose or [U-13C3]serine as precursors, respectively. Overall 13C excess (mol %) of labeled amino acids and PHB is given by a color map in a quasilogarithmic form to show even relatively small 13C excess values. PHB indicated by white boxes could not be measured. Each sample (from individual labeling experiments indicated by a–r) was measured three times; the color for each amino acid correlates with the mean value of the three measurements. Arrows on top of the color code indicate the change in the relative incorporation rates during the growth phases. C, corresponding labeling data for the Δketo mutant devoid of Lpp1788, a putative key enzyme in providing the 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA precursor for PHB biosynthesis.

Workup of L. pneumophila Cells

Extraction with dichloromethane and the acidic hydrolysis of the residual bacterial pellets were done as described earlier (19). The acidic treatment converted Asn and Gln into Asp and Glu. The labeling data given for Asp and Glu therefore represent Asn/Asp and Gln/Glu averages, respectively. Cys, Trp, and Met were destroyed during the harsh conditions of acidic hydrolysis. The resulting amino acids (from proteins) and 3-hydroxybutyrate (from PHB) were converted into N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl) derivatives or trimethylsilyl derivatives, respectively, as described (19).

Mass Spectrometry and Isotopologue Analysis

N-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)-amino acids and trimethylsilyl-3-hydroxybutyrate were analyzed by GC-MS using a GCMS-QP 2010 Plus spectrometer (Shimadzu, Duisburg, Germany) as described earlier (19). The yields of N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-Arg were too low for isotopologue analysis. Data were collected using the GC/MS Lab Solutions Version 2 software (Shimadzu). Samples were analyzed at least three times. The overall 13C excess (mol %) and the relative contributions of isotopomers (%) were computed by an Excel-based in-house software package according to Eylert et al. (19) and Lee et al. (44).

NMR Spectroscopy

13C NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C using an Avance III 500-MHz spectrometer (Bruker Instruments, Karlsruhe, Germany). Extracts with dichloromethane were measured in CDCl3.

FTIR Spectroscopy of Whole L. pneumophila Cells to Quantify PHB

Bacteria were grown in AYE broth to EE, LE, PE, and S phases. After centrifugation of the bacterial suspensions (7 ml; A600 nm = 1) at 4,600 × g for 15 min, the bacterial pellets were washed three times with distilled water and then resuspended; the amount of distilled water was specifically adjusted to the pellet size. A suspension volume of 35 μl was then transferred onto a ZnSe sample holder and dried to a film in a desiccator under moderate vacuum (0.9 bar) over P2O10 (Sicapent, Merck) for ∼30 min. Prior to FTIR measurements, the sample holder was sealed with a KBr cover plate. FTIR test measurements with eight individual sample scans were subsequently conducted to assure that the absorption values of the most intensive IR band, the amide I band (1,620–1,690 cm−1), varied between predefined quality test threshold values of 0.345 and 1.245 absorbance units (45). New samples were prepared in cases where the quality tests failed and checked again by the quality test.

FTIR spectra were acquired from bacterial samples (three independent cultivations for each strain and growth phase) by means of an IFS 28/B FTIR spectrometer from Bruker Optics (Ettlingen, Germany). The instrument was equipped with a deuterated triglycine sulfate detector, a mid-IR globar source, a KBr beam splitter, and a 15-position multisampling sample wheel that allowed for automated measurements of dried film samples. Background spectra were collected from an empty position of the ZnSe sample wheel. The software used to record and analyze the FTIR spectra was OPUS 5.0 (Bruker Optics). Sample and background spectra were measured by co-adding 64 individual sample scans. Spectra were acquired in absorbance/transmission mode in the spectral range between 500 and 4,000 cm−1. Nominal resolution was 6 cm−1, and a zero-filling factor of 4 was applied, giving a point spacing of ∼1 cm−1.

Results and Discussion

Construction and Growth Characterization of L. pneumophila Mutant Strains Defective in PHB Formation

lpp0650 encodes one of the four putative PHB polymerases in L. pneumophila, and lpp1788 putatively encodes the 3-ketothiolase reaction (14, 32) (Fig. 1). The gene cluster lpp0931–33 encodes an acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (lpp0931), an enoyl-CoA hydratase (lpp0932), and a crotonyl-CoA hydratase involved in fatty acid metabolism. However, these enzymes might also be involved in PHB formation from butanoyl-CoA (generated by degradation of fatty acids) via crotonyl-CoA to (R)-OH-butanoyl-CoA, thereby bypassing the 3-ketothiolase reaction (Fig. 1). To substantiate the roles of these gene products in PHB metabolism, we constructed deletion mutants of L. pneumophila devoid of lpp0650 (ΔPHB polymerase), lpp1788 (Δketo), or lpp0931–33. Moreover, Δlpp0931–33/Δketo double mutant strains were constructed. All genes mentioned above are generally present in the thus far available genomes of Legionella strains, underlining the general character of this study.

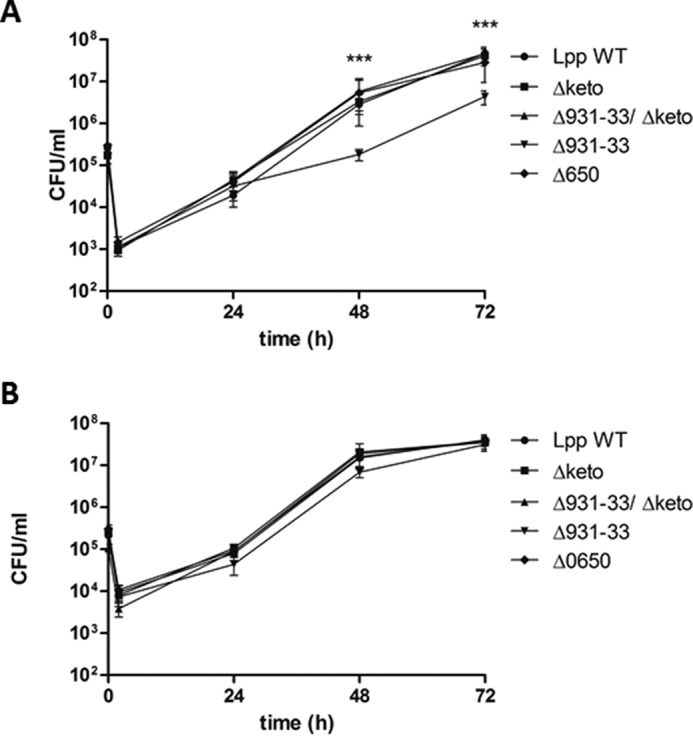

In AYE medium at 37 °C, all of these mutants grew nearly similar to the wild type strain (Fig. 3A). However, we recognized that the Δketo strain exhibited a prolonged lag phase, but then it replicated as fast as the wild type strain. In addition, no defect of the Δketo mutant strain could be detected in a replication/survival assay using A. castellanii as host cells (14). The Δlpp0931–33, Δketo/Δlpp0931–33, and the Δlpp0650 mutant strains also showed no defect in the intracellular replication assay over 72 h using A. castellanii as the host (Fig. 4B). Obviously, PHB metabolism was not affected in the mutants under study, or it was not relevant for the intracellular conditions in the replication/survival assays until the late exponential phase of L. pneumophila in A. castellanii. However, it cannot be ruled out that survival and infectivity of the L. pneumophila mutants are impaired in infected amoebae under environmental viable but non-culturable conditions.

FIGURE 3.

Growth phase-dependent amounts of PHB in L. pneumophila Paris WT and the isogenic mutant strains Δketo, Δlpp0931–33, Δlpp0931–33/Δketo, and Δlpp0650. A, growth curve of L. pneumophila strains grown in AYE medium at 37 °C. Time points (EE, LE, PE, and S) of PHB measurement are indicated by arrows. B, Western blotting analysis of L. pneumophila Paris WT (lane 1), Δketo (lane 2), Δlpp0931–33/Δketo (lane 3), Δlpp0931–33 (lane 4), and Δlpp0650 (lane 5) using an anti-FlaA antiserum. M, protein marker. C, preprocessed FTIR spectra demonstrating the relative amount of PHB of L. pneumophila Paris (Lpp WT) and isogenic Δketo mutant strain (Lpp Δketo) in AYE medium at 37 °C at EE, LE, PE, and S phases of growth. The C=O ester (PHB) and amide II (protein) bands are indicated. The amount of PHB in the L. pneumophila Δketo mutant strain increased in the PE and S phases when compared with the L. pneumophila WT strain. D, relative PHB amounts in L. pneumophila Paris strains investigated by FTIR spectroscopy. All values are mean values of triplicate determinations (±S.D. represented by error bars) and are given in relative intensity units (see Fig. 5). Additional values given are in percent with respect to the relative PHB content of L. pneumophila WT in the PE phase.

FIGURE 4.

Co-culture of various L. pneumophila Paris strains with U937 cells (A) and A. castellanii (B). Bacteria were used to infect host cells at a multiplicity of infection of 1 for 72 h. At various time points postinoculation, bacteria were quantified by plating aliquots on buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar plates to determine the CFU/ml. Results are means ± S.D. (error bars) of duplicate samples and are representative of at least three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences in the growth of Δlpp0931–33 strain compare with the wild type strain (determined by a Student's t test, p < 0.001) are indicated (***). Lpp, L. pneumophila Paris; Δ, isogenic mutant strains of Lpp; 0931–33, lpp0931–33; 0650, lpp0650; keto, lpp1788.

The growth behavior of L. pneumophila mutants in A. castellanii could also be observed in infection assays using human macrophage-like U937 cells with the exception of strain Δlpp0931–33, which displayed a slightly reduced capacity of intracellular replication (Fig. 4A). Notably, this phenotype was observed for two independently generated Δlpp0931–33 mutant strains, and it therefore appears less probable that second site mutations caused this effect. Indeed, the reduced growth might be explained by a ΔLpp0931–33-dependent decrease in the concentrations of acylated acyl carrier proteins, which are measured by the stringent response enzyme SpoT in L. pneumophila and could lead to a change in the expression of the transmissive phenotype (cell cycle) as reported earlier (46). Conversely, this phenotype could be suppressed by the additional inactivation of the ketothiolase in the Δketo/Δlpp0931–33 double mutant by blocking the conversion of Ac-CoA into acetoacetyl-CoA, thereby also influencing (i.e. increasing) the amounts of acetylated acyl carrier proteins and finally resulting in the unaffected growth behavior of the Δketo/Δlpp0931–33 double mutant.

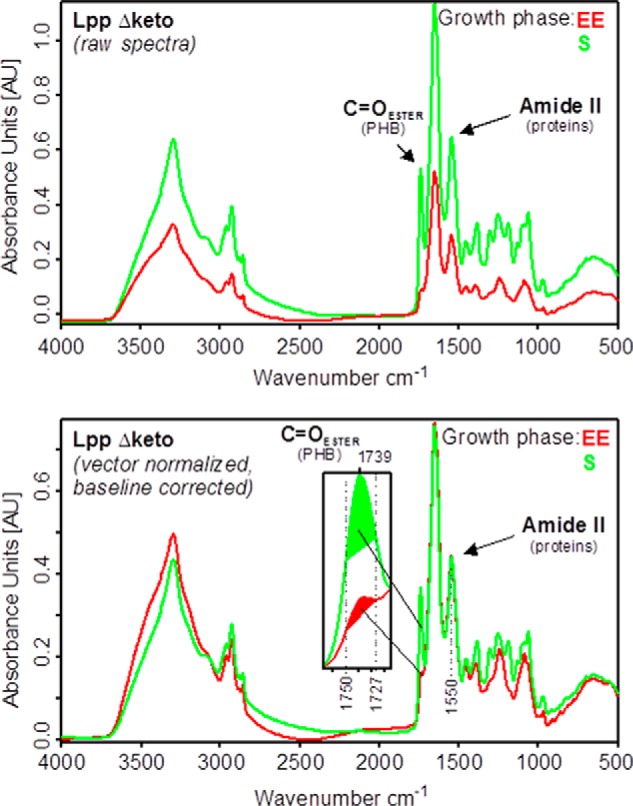

Determination of PHB by FTIR Measurements of Whole Cells

To directly address the question of PHB metabolism, we next quantified the relative PHB amounts in the strains under study by means of Nile red staining (data not shown) and FTIR spectroscopy of whole intact cells from different growth phases. For this purpose, absorbance spectra from three independent cultivations per L. pneumophila strain and growth phase were measured and preprocessed. Preprocessing involved vector normalization in the spectral region of the amide II band between 1,480 and 1,590 cm−1 and baseline correction (Fig. 5), which assures equal scaling of the spectra in the amide II region. The amide II band can be considered as a measure of the total protein mass of microbial cells, whereas the amount of PHB is represented by the intensity of the ester carbonyl band at 1,739 cm−1. On this basis, relative amounts of PHB can be determined from the preprocessed FTIR spectra by calculating the integral absorbance of the carbonyl ester band between 1,727 and 1,750 cm−1 (Fig. 5, lower panel). Furthermore, percentage values with regard to the PHB content of L. pneumophila Paris WT in the PE phase were obtained by setting this specific value to 100%.

FIGURE 5.

Determination of the relative PHB amounts from whole intact cells of L. pneumophila. Upper panel, original (raw) absorbance spectra of L. pneumophila Paris Δketo (Lpp Δketo). Lower panel, preprocessed absorbance spectra of L. pneumophila Paris Δketo. Preprocessing involved vector normalization in the amide II region (1520–1570 cm−1) and offset correction. The intensity of the ester carbonyl band around 1739 cm−1 of spectra normalized to the amide II band can be used to determine the relative amount of PHB present in the cells. For this purpose, the areas under the curves are calculated between 1727 and 1750 cm−1 (see inset of the lower panel).

Using this procedure, we analyzed the L. pneumophila Paris wild type and Δketo, Δlpp0931–33, Δlpp0931–33/Δketo double, and lpp0650 mutant strains. For this purpose, the mentioned strains were grown at 37 °C in AYE medium (inoculation, A600 = 0.3) and harvested at A600 = 1.0 (EE phase), A600 = 1.5 (LE phase), A600 = 1.9 (PE phase), and A600 = 1.9 plus an additional 17 h of growth (S phase), respectively (Fig. 3A). As a control for the growth phases, we analyzed the expression of flagellin (FlaA) by L. pneumophila harvested at the indicated growth phase because it is known that the expression of flagellin is highly induced in PE phase of L. pneumophila (2, 47). As expected, the bacteria did not express flagellin in the replicative phase (EE + LE), whereas FlaA was detected in PE and S phases (Fig. 3B).

In Fig. 3C, the absorbance spectra used to determine the relative PHB amounts of the different strains under study are given exemplarily for L. pneumophila WT and the isogenic Δketo mutant strain. Table 2 shows the relative amounts of PHB normalized to the PHB content of L. pneumophila WT cells in the PE phase (see also Fig. 3D). The spectra in Fig. 3C and the relative PHB values in Fig. 3D demonstrate for the wild type strain a reduced PHB content during the replicative phase varying between 37 and 45% with respect to the PHB content in the PE phase (Table 2). The PHB content increased from the LE phase (37%) to the PE growth phase (100% PHB), and then the amount of PHB again decreased (46%; see Fig. 3D and Table 2), corroborating that PHB was catabolized during the stationary phase of growth. It can be concluded that L. pneumophila WT assembles PHB until the PE phase when entering the transmissive phase where the bacteria then use their PHB storage as an energy source and probably also to provide NADPH by PHB degradation and as a carbon source to provide Ac-CoA for the reduced carbon metabolism during the transmissive phase.

TABLE 2.

PHB content (in %) of L. pneumophila strains as seen by FT-IR spectroscopy

Percentage values (mean values from three independent cultivations) were obtained from experimental FT-IR spectra with respect to the PHB content of Lpp WT in the PE phase. The data were normalized to the 100 (in bold) for WT (PE).

| Lpp strain | EE | LE | PE | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 45 | 37 | 100 | 46 |

| Δketo | 51 | 69 | 131 | 201 |

| Δ0931–33 | 55 | 37 | 79 | 62 |

| Δ0931–33/Δketo | 84 | 100 | 152 | 203 |

| Δ0650 | 12 | 10 | 15 | 10 |

In comparison with the WT, the amount of PHB in the Δketo mutant strain was found to be increased during the late PE and the S phase (∼200%) (Fig. 3D and Table 2). In sharp contrast to the WT, the increased amount of PHB did not significantly decrease during the S phase (Fig. 3, C and D, Δketo). Surprisingly, the relative amount of PHB of the lpp0650 mutant devoid of one of the putative PHB polymerases was only about 15% of that of the wild type strain at PE phase, although only one of the four PHB polymerases was inactivated (Fig. 3D and Table 2). This indicates that lpp0650 encodes the major PHB polymerase during in vitro growth of L. pneumophila Paris at 37 °C. However, the deletion of the FAD-dependent crotonyl-CoA pathway (lpp0931–33) had only a small influence on the synthesis of PHB (79% in comparison with the WT level). The double mutant strain behaved like the Δketo mutant strain; the synthesis of PHB during the replicative phase of both mutant strains was increased (about 200% of WT level; see Fig. 3D and Table 2). These results reflected that the FAD-dependent crotonyl-CoA pathway (lpp0931–33) has only a limited influence on the metabolism of PHB. Furthermore, in the Δketo mutant (lpp1788), PHB was not significantly degraded during the S phase (Table 2), demonstrating that lpp1788 is important for the degradation of PHB as well as for the synthesis of PHB (Fig. 1). An earlier study reported that a bdhA-patD mutant strain of L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 exhibits a 2-fold increased amount of PHB when compared with the WT strain (48). BdhA is a 3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase, and the authors hypothesized that this enzyme is involved in the degradation of PHB. The homolog of bdhA in L. pneumophila Paris is lpp2264 (see Fig. 1). Interestingly, the inactivation of PHB degradation by deletion of lpp1788 in L. pneumophila Paris or bdhA in L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 (lpp2264 homolog) led to a similar double-fold increased amount of PHB in the respective bacteria (48).

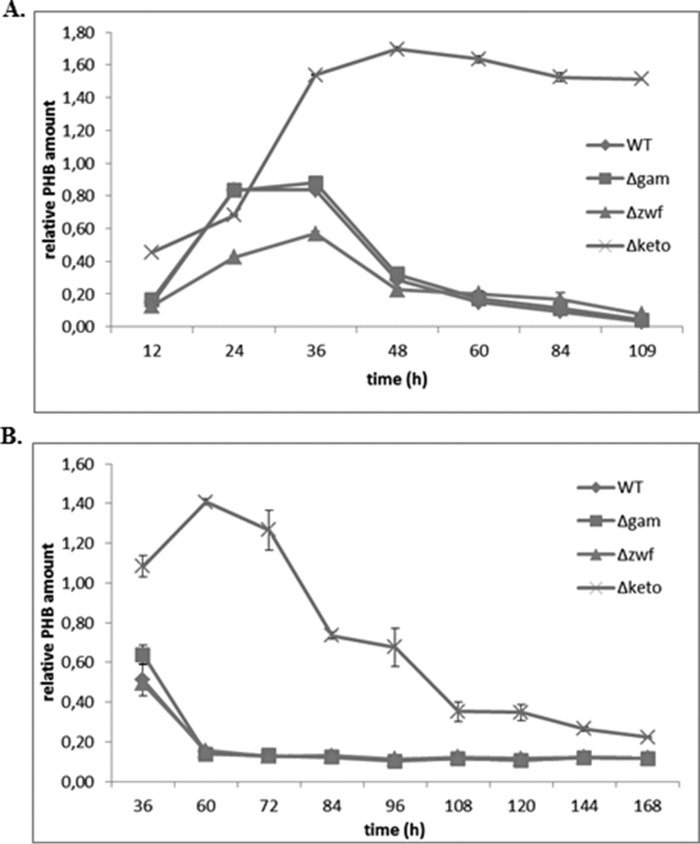

In an additional experiment, we found that a Δzwf mutant of L. pneumophila (zwf gene encodes the first enzyme (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) of the ED pathway) synthesized lesser amounts of PHB compared with the wild type (68%; Fig. 6A), which is an indication that the ED pathway of glucose catabolism is connected with PHB biosynthesis (19). In addition, it also supports the published role of the ED pathway for the life cycle of L. pneumophila (19, 33). The gamA gene encodes a glucoamylase responsible for the glycogen-degrading activity of L. pneumophila Paris, but the inactivation of gamA had no effect on intracellular replication in A. castellanii (34). As expected, the amount of PHB of the Δgam mutant strain was similar to that of the WT strain (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, this experiment also revealed that the amount of PHB in the wild type strain was rapidly degraded during prolonged incubation in medium or on agar plates (Fig. 6B). However, the amount of PHB in the Δketo mutant strain remained nearly constant during stationary growth (measured up to 108 h) in medium, whereas on agar plates the amount of PHB was decreased during prolonged stationary growth. Consequently, the metabolism of PHB in the Δketo mutant strain depends on the growth conditions (i.e. grown in liquid medium or on a surface). This could point at a distinct role of PHB degradation in viable but non-culturable L. pneumophila WT and its Δketo mutant strain.

FIGURE 6.

Growth-dependent relative amounts of PHB in L. pneumophila Paris WT and the isogenic mutant strains Δgam, Δzwf, and Δketo at 37 °C in AYE medium (A) and on buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar plates (B) investigated by FTIR spectroscopy. All values are means ± S.D. (error bars) of duplicate determinations and are given in relative integrated intensity units (see Fig. 5).

Growth Phase-dependent Utilization of Serine and Glucose by L. pneumophila Paris WT

To investigate in more detail the role of potential carbon sources in PHB formation during the different growth phases of L. pneumophila, we analyzed the utilization of exogenous serine and glucose throughout the life cycle of the bacterium. For this purpose, we performed labeling experiments of L. pneumophila Paris growing in AYE medium containing [U-13C3]Ser or [U-13C6]glucose, respectively. The bacteria were grown at 37 °C with one of the labeled substrates from the inoculation time (A600 = 0.1) to A600 = 1.0 (EE phase), from A600 = 1.0 to 1.5 (LE phase), from A600 = 1.5 to 1.9 (PE phase), and from A600 = 1.9 plus an additional 17 h of growth (S phase), respectively (see Fig. 2A). The cells were extracted with dichloromethane, and the extract was analyzed by NMR spectroscopy. The 13C NMR spectra displayed four intense signals with the known chemical shifts of PHB (19) (data not shown). Because of multiple 13C labeling, each of these signals (corresponding to C-1–C-4 of the 3-hydroxybutyrate units in PHB) was characterized by a central singlet (corresponding to 13C1 isotopologues) and a doublet (corresponding to 13C2 isotopologues) as described earlier (19). On the basis of the coupling constants gleaned from the doublets, it was clearly evident that labeled PHB consisted of a mixture of [1,2-13C2]- and [3,4-13C2]-isotopologues that can be explained by the biosynthetic pathway starting from [1,2-13C2]Ac-CoA (see also Fig. 1). Notably, alternative coupling patterns reflecting different routes (i.e. not via 3-hydroxy[1,2-13C2]butyryl-CoA or 3-hydroxy[3,4-13C2]butyryl-CoA made from [1,2-13C2]Ac-CoA) were not detected in any of the PHB samples. In contrast, the relative rates of 13C incorporation of [1,2-13C2]Ac-CoA into PHB were clearly different in the various mutants as seen from the relative signal intensities of the 13C-coupled signal pairs in comparison with the central signals. For example, the relative sizes of the 13C-coupled doublets appeared smaller in PHB from the Δketo mutant than from the wild type strain. This was surprising because the amount of PHB in the Δketo mutant was much higher than in the wild type strain (see above).

These differences in 13C enrichments were therefore analyzed in closer detail by GC-MS analysis of the PHB hydrolysates. For this purpose, PHB (used for NMR analyses) and the residual cell mass (i.e. after hexane extraction) were hydrolyzed under acidic conditions. The resulting 3-hydroxybutyrate and amino acids were silylated and analyzed by mass spectrometry. MS-based isotopologue profiling of amino acids (from the proteins) and 3-hydroxybutyrate (from PHB) provided accurate quantitative information about the relative incorporation of 13C-labeled Ser or glucose during the various growth phases of L. pneumophila (Fig. 2B).

Using [U-13C6]glucose as a supplement, we could not detect significant 13C incorporation (>1% 13C excess) into Ser, His, Ile, Leu, Val, and Thr during any growth phase. Apparently, these amino acids were taken up (in unlabeled form) from the complex AYE medium and directly incorporated into bacterial protein. Conversely, Ala, Asp, Glu, Gly, and 3-hydroxybutyrate acquired significant label from [U-13C6]glucose in agreement with our earlier studies (19). Notably and in extension to the results from the earlier study, the incorporation rates of [U-13C6]glucose into these metabolites significantly varied during the growth phases under study. Specifically, the relative incorporation of glucose into amino acids was very low during the EE phase (Ala, 1.5%; Glu, 0.5%; Asp, 0.2%). 3-Hydroxybutyrate from PHB was not detectable from these early bacteria. However, the incorporation of glucose strongly increased from the LE (Ala, 2.2%; Glu, 0.9%; Asp, 0.3%; PHB, 2.6%) to the PE phase (Ala, 5.3%; Glu, 3%; Asp, 1.2%; PHB, 6.2%) (Fig. 7A). The corresponding incorporation values detected in the S phase were nearly the same as in the PE phase with the exception of Gly that only acquired label from glucose during the S phase (Fig. 2B). The isotopologue compositions in the labeled amino acids (data not shown) reflected the well known glucose degradation via the Entner-Doudoroff pathway and the citrate cycle as already described earlier in detail (19). The mass pattern in 3-hydroxybutyrate again confirmed PHB formation using [1,2-13C2]Ac-CoA units as precursors. Notably, in all metabolites under study, the relative fractions of the key isotopologues did not significantly change during the different phases of growth. This indicated that the pathways of glucose utilization were growth phase-independent. However, it should be emphasized again that the efficiencies to use these pathways were growth-rate dependent as seen from the different overall 13C enrichments (Fig. 2B).

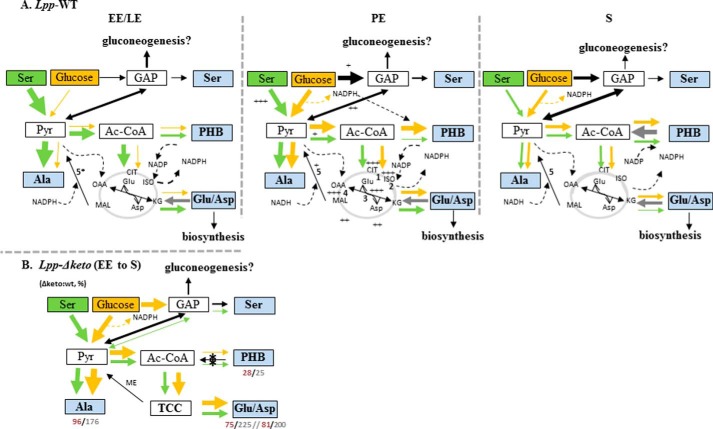

FIGURE 7.

Flux model for PHB and amino acid metabolism in L. pneumophila Paris growing in AYE medium during different growth phases. A, carbon flux in L. pneumophila Paris (Lpp) during the exponential (EE and LE), PE, and late S phase using serine (green arrows) or glucose (yellow arrows) as a substrate. Relative carbon fluxes are indicated by the thickness of the arrows. The citrate cycle is indicated in gray. + to +++, enzymatic activity measured by Keen and Hoffman (30); 1, aconitase; 2, isocitrate dehydrogenase; 3, Glu/Asp transaminase; 4, malate dehydrogenase; 5, malic enzyme (ME; lpp3043 and lpp0705 (5*)). B, carbon flux in L. pneumophila Paris Δketo mutant strain in comparison with the wild type strain measured at the end of the growth phase. The ratios (Δketo mutant/wild type) of incorporation (13C mol %) of serine and glucose into selected amino acids or PHB are indicated by red or gray numbers, respectively. *, inactivated lpp1788 (β-ketothiolase). GAP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; ISO, isocitrate; CIT, citrate; KG, ketoglutarate; MAL, malate; OAA, oxaloacetate; TCC, tricarboxylic acid cycle.

In sharp contrast to the [13C]glucose experiment, [U-13C3]Ser was efficiently incorporated into amino acids already during the EE phase (Ala, 18%; Glu, 8%; Asp, 4%; Ser, 54%) and into amino acids and PHB during the LE phase (Ala, 13%; Glu, 5.5%; Asp, 2.3%; Ser, 28%; 3-hydroxybutyrate, 11.8%). When reaching the PE phase, these values further decreased (Ala, 4.6%; Glu, 1.8%; Asp, 1%; Ser, 6.5%; 3-hydroxybutyrate, 1.9%) (Fig. 2B).

Notably, in the PE phase the 13C excess value for Ser was only 6.5%. In the S phase, the incorporation rate again slightly increased (Ala, 6%; Glu, 2.7%; Asp, 1.4%; Ser, 7%; 3-hydroxybutyrate, 7.2%) probably due to a specific serine transport protein (Lpp2269) whose expression is induced during the transmissive phase (13). Interestingly, from the PE to the S phase, the amounts of M + 1 and M + 2 of [13C]Ser increased, although “fresh” [U-13C3]Ser was added and was therefore still present in the medium but was probably not taken up by L. pneumophila. Rather, the increasing amounts of M + 1 and M + 2 of [13C]Ser may be due to anaplerotic reactions generating [13C2]pyruvate from [13C2]oxaloacetate by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase activity or from malate by malic enzyme activity. The transcription of this gene (lpp3043) is up-regulated in the PE phase (13).

A summarizing model for the growth phase-dependent carbon flux from Ser and glucose is shown in Fig. 7A. In the replicative phase (EE + LE), Ser is directly used for protein biosynthesis (54 mol % [13C3]Ser) but also converted into [13C3]pyruvate (as shown by the detection of M + 3 Ala). Moreover, [13C3]pyruvate affords [13C2]Ac-CoA and, via the TCA, α-[13C2]ketoglutarate and [13C2]oxaloacetate (as shown by the detection of M + 2 Glu and Asp, respectively). High activity of the TCA could also indicate the large demand for energy during the replicative phase. During the LE phase, there is also considerable flux from Ser into PHB via Ac-CoA. In sharp contrast, label from glucose is not efficiently transferred into pyruvate and Ac-CoA used for amino acid and PHB formation during the replicative phase of growth, which is in good agreement with the observation that glucose is not efficiently taken up by L. pneumophila during the exponential phase of growth (33). Thus, the results indicate that until the LE phase the citrate cycle is highly active where the majority of Ac-CoA enters the citrate cycle, enabling formation of NADH and NADPH that are important for ATP synthesis and other biosynthesis reactions, respectively. This is supported by the results of transcriptome studies demonstrating that, for example, genes encoding pyruvate dehydrogenase, NADH dehydrogenase, and H+-ATP synthase and genes involved in fatty acid synthesis are up-regulated in the exponential phase (13).

The utilization of Ser and glucose by L. pneumophila Paris changed when entering the PE phase of growth at which point carbon flux from glucose to pyruvate/Ala and PHB via Ac-CoA increased. Glucose-derived Ac-CoA was also shuffled to some extent into the TCA as shown by incorporation of [13C]glucose into α-ketoglutarate/Glu and oxaloacetate/Asp during this period. In contrast, incorporation from Ser decreased during the PE phase as compared with the replicative phase. The slight increase of flux from Ser to some amino acids during the S phase (Fig. 2B) may be explained by the depletion of amino acids and nutrients from the medium, which then could again lead to an increased uptake of the supplemented [13C3]Ser from the medium. This suggestion is supported by the above mentioned expression of a specific Ser uptake protein (Lpp2269) in the PE phase of growth (13).

In summary, the results provide strong evidence that Ser (or amino acids in general) is the dominant carbon source(s) during replication, whereas glucose is additionally used during the PE phase mainly to generate PHB, the carbon and energy resource of L. pneumophila. However, it cannot be excluded that glucose (or sugars in general) is also incorporated into carbohydrates and cell wall components of L. pneumophila because these products were not analyzed in our study. Remarkably, the role of gluconeogenesis for the metabolism of L. pneumophila is still unclear (16, 20).

NADPH generated by the degradation of glucose via the ED pathway and the citrate cycle involving an NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (Fig. 7A) is probably directly connected to PHB biosynthesis. Indeed, it was suggested that PHB in bacteria plays a role as a redox regulator (5). Further substantiating this hypothesis, in the PE phase of L. pneumophila, genes responsible for anaplerotic reactions (malic enzyme (lpp3043), pyruvate decarboxylase (lpp1157), and the 3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (lpp2264)) as well as genes encoding proteins for PHB synthesis (see Fig. 1), citrate synthase, aconitase, and Glu/Asp transaminase, were reported to be up-regulated (13). In addition, high enzymatic activities (see Fig. 7A, PE, + to +++) were demonstrated for some of these gene products (30).

Growth Phase-dependent Usage of Ser and Glucose by the Δketo Strain of L. pneumophila Paris

To understand why the amount of PHB was found increased in the Δketo mutant devoid of Lpp1788, a putative key enzyme in providing the 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA precursor for PHB biosynthesis (see Fig. 2A), we performed the growth phase-dependent labeling experiments with the Δketo mutant strain as described above for the wild type strain. Surprisingly, during all growth phases of the mutant, the incorporation of [U-13C6]glucose or [U-13C3]Ser into PHB was very low despite the increased amounts of PHB as compared with the wild type strain (Fig. 3D). Conversely, the 13C enrichments (Fig. 2C) and isotopologue profiles of amino acids were quite similar to the corresponding data in the wild type strain. More specifically, 13C excess values using [U-13C3]Ser as a substrate were only slightly decreased in the mutant during the EE and LE phases (EE (mutant/WT): Ala, 15%/18%; Glu, 6%/8%; Asp, 3%/4%; Ser, 47%/54%) but increased during the PE and S phases (PE (mutant/WT): Ala, 9%/4.6%; Glu, 3.8%/1.8%; Asp, 1.0%/4%; Ser, 12.8%/6.5%) (Fig. 2C). Thus, whereas the incorporation of Ser into PHB of the mutant was highly reduced (by about 72% in comparison with the wild type), incorporation into amino acids was only moderately reduced in the Δketo mutant (by 1–10%). This indicates that Lpp1788 is the key enzyme in the formation of 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA during the replicative phase of L. pneumophila.

Carbon flux from glucose into PHB from the Δketo mutant was also decreased in agreement with the conclusion made above. The fact that some amino acids from the Δketo mutant acquired more 13C label from [U-13C6]glucose could reflect that the carbon flux from Ac-CoA (that is not consumed because of the loss of Lpp1788) is now shuffled into the citrate cycle (Glu and Asp) and to pyruvate (Ala). However, the still existing formation of labeled PHB in the mutant may be explained by the activity of two further enzymes (Lpp1307 and Lpp1555) with putative 3-ketothiolase activity and/or by additional pathways feeding the PHB biosynthesis pathway (e.g. via degradation of fatty acids or ketogenic amino acids such as Leu or Lys; see Fig. 1). However, the origin of the high amount of unlabeled PHB in the Δketo mutant strain is not known. Most likely there is another link from fatty acids (other than lpp0931–33) like the 3-ketoacyl-CoA reductase activity in pseudomonads (49, 50) or from ketogenic amino acids. Further research is necessary to complete the metabolic network involved in PHB biosynthesis and degradation. However, the present study provides for the first time functional information about the key players in this network during the various growth phases of L. pneumophila.

Conclusion

13C labeling experiments and whole-cell FTIR analyses show that PHB is generated by L. pneumophila mainly during the postexponential growth phase using Ac-CoA units. During this late phase of growth, exogenous glucose significantly contributes to the formation of the Ac-CoA precursor units, whereas during the earlier growth phase, serine is among the major carbon substrates of L. pneumophila. Comparative analyses using a set of mutants of L. pneumophila defective in potential key elements of PHB metabolism demonstrate that Lpp0650, one of the four potential PHB polymerases in L. pneumophila, is involved in the biosynthesis of most PHB (>80%). Although the Δlpp0650 mutant was not significantly hampered in intracellular growth inside the natural host, A. castellannii, or in the human macrophage-like U937 cells, the enzyme could play an essential role during the life cycle of environmental L. pneumophila, e.g. under extracellular conditions when forming biofilms. Our data also show that the putative 3-ketothiolase, Lpp1788, but not enzymes of the crotonyl-CoA pathway, Lpp0931–33, are relevant for PHB degradation under the experimental in vitro conditions of our study. Although during the stationary growth phase the amount of PHB was decreased in the wild type strain, this degradation was not observed in the Δlpp1788 mutant. Interestingly, however, the biosynthesis of PHB was not decreased by loss of the same ketothiolase (Lpp1788) because the Δlpp1788 mutant assembled even more PHB than the wild type. Because the incorporation rates of exogenous [13C]serine or glucose into mutant PHB were lower, it must be assumed that another unlabeled substrate present in the medium efficiently serves as an alternative substrate to provide precursors for PHB. The example shows the adaptive capabilities of L. pneumophila under changing environmental conditions.

Another example of this adaptive response upon changing metabolic conditions is given by the observed differential usage of serine or glucose as carbon substrates during the growth phases of L. pneumophila. Specifically, serine is a preferred substrate during the exponential growth phase. Serine (and other amino acids) is then directly used for protein biosynthesis but also catabolized mainly via the TCA to generate precursors for other biosynthetic reactions including amino acids and reduction equivalents for ATP synthesis. Recently, we demonstrated that this substrate usage is also true for intracellular multiplying L. pneumophila in A. castellanii (14).

In contrast, glucose is metabolized during the postexponential phase where it contributes to PHB formation by providing its Ac-CoA precursors via degradation to pyruvate by the ED pathway and further to Ac-CoA. Following this feature, the synthesis of PHB is also induced during the PE phase. In line with earlier observations (15), glucose may therefore be an important additional substrate under intracellular conditions to feed the biosynthesis of PHB when the bacteria become virulent, leave the vacuoles, and meet new substrates such as glucose in the cytosolic compartment of the host cell (20, 52). Notably, glucose could also be generated from cytosolic glycogen of the host cells by the action of the bacterial glycogen-degrading enzyme GamA (34). In any case, the observed shifts in substrate usage can be taken as another piece of evidence that metabolic adaptation is a key element in the lifestyle of Legionella.

Author Contributions

K. H. and W. E. designed the study and wrote the paper. N. G. and E. K. performed isotopologue profiling. E. S., H. T., K. R., and V. H. performed the biological experiments. M. S. and P. L. performed whole-cell FTIR experiments. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Grants EI 384/4-2 and HE 2845/6-1 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG SPP1316, Bonn, Germany (to W. E. and K. H., respectively) and the Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- PHB

- poly-3-hydroxybutyrate

- AYE

- ACES-buffered yeast extract

- E

- exponential

- ED

- Entner-Doudoroff pathway

- EE

- early exponential

- LE

- late exponential

- LE

- late exponential

- PE

- postexponential

- PYG

- peptone yeast glucose

- S

- stationary

- TCA

- citrate cycle

- ACES

- N-(2-acetoamido)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid.

References

- 1. Garduño R. A., Garduño E., Hiltz M., and Hoffman P. S. (2002) Intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila gives rise to a differentiated form dissimilar to stationary-phase forms. Infect. Immun. 70, 6273–6283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heuner K., Brand B. C., and Hacker J. (1999) The expression of the flagellum of Legionella pneumophila is modulated by different environmental factors. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 175, 69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Molofsky A. B., and Swanson M. S. (2004) Differentiate to thrive: lessons from the Legionella pneumophila life cycle. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Robertson P., Abdelhady H., and Garduño R. A. (2014) The many forms of a pleomorphic bacterial pathogen-the developmental network of Legionella pneumophila. Front. Microbiol. 5, 670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anderson A. J., and Dawes E. A. (1990) Occurrence, metabolism, metabolic role, and industrial uses of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microbiol. Rev. 54, 450–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anderson A. J., Haywood G. W., and Dawes E. A. (1990) Biosynthesis and composition of bacterial poly(hydroxyalkanoates). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 12, 102–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. James B. W., Mauchline W. S., Dennis P. J., Keevil C. W., and Wait R. (1999) Poly-3-hydroxybutyrate in Legionella pneumophila, an energy source for survival in low-nutrient environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 822–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kadouri D., Jurkevitch E., Okon Y., and Castro-Sowinski S. (2005) Ecological and agricultural significance of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 31, 55–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mauchline W. S., Araujo R., Wait R., Dowsett A. B., Dennis P. J., and Keevil C. W. (1992) Physiology and morphology of Legionella pneumophila in continuous culture at low oxygen concentration. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138, 2371–2380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rowbotham T. J. (1986) Current views on the relationships between amoebae, legionellae and man. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 22, 678–689 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ngo Thi N. A., and Naumann D. (2007) Investigating the heterogeneity of cell growth in microbial colonies by FTIR microspectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 387, 1769–1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oldham L. J., and Rodgers F. G. (1985) Adhesion, penetration and intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila: an in vitro model of pathogenesis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 131, 697–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brüggemann H., Hagman A., Jules M., Sismeiro O., Dillies M. A., Gouyette C., Kunst F., Steinert M., Heuner K., Coppée J. Y., and Buchrieser C. (2006) Virulence strategies for infecting phagocytes deduced from the in vivo transcriptional program of Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 1228–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schunder E., Gillmaier N., Kutzner E., Eisenreich W., Herrmann V., Lautner M., and Heuner K. (2014) Amino acid uptake and metabolism of Legionella pneumophila hosted by Acanthamoeba castellanii. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 21040–21054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tesh M. J., Morse S. A., and Miller R. D. (1983) Intermediary metabolism in Legionella pneumophila: utilization of amino acids and other compounds as energy sources. J. Bacteriol. 154, 1104–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoffman P. S. (2008) Microbial physiology, in Legionella pneumophila: Pathogenesis and Immunity (Hoffman P. S., Klein T., and Friedman H., eds) pp. 113–131, Springer Publishing Corp., New York [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hayashi T., Nakamichi M., Naitou H., Ohashi N., Imai Y., and Miyake M. (2010) Proteomic analysis of growth phase-dependent expression of Legionella pneumophila proteins which involves regulation of bacterial virulence traits. PLoS One 5, e11718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reich-Slotky R., Kabbash C. A., Della-Latta P., Blanchard J. S., Feinmark S. J., Freeman S., Kaplan G., Shuman H. A., and Silverstein S. C. (2009) Gemfibrozil inhibits Legionella pneumophila and Mycobacterium tuberculosis enoyl coenzyme A reductases and blocks intracellular growth of these bacteria in macrophages. J. Bacteriol. 191, 5262–5271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eylert E., Herrmann V., Jules M., Gillmaier N., Lautner M., Buchrieser C., Eisenreich W., and Heuner K. (2010) Isotopologue profiling of Legionella pneumophila: role of serine and glucose as carbon substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22232–22243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fonseca M. V., and Swanson M. S. (2014) Nutrient salvaging and metabolism by the intracellular pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 4, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. George J. R., Pine L., Reeves M. W., and Harrell W. K. (1980) Amino acid requirements of Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Microbiol. 11, 286–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pine L., George J. R., Reeves M. W., and Harrell W. K. (1979) Development of a chemically defined liquid medium for growth of Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Microbiol. 9, 615–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tesh M. J., and Miller R. D. (1981) Amino acid requirements for Legionella pneumophila growth. J. Clin. Microbiol. 13, 865–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reeves M. W., Pine L., Hutner S. H., George J. R., and Harrell W. K. (1981) Metal requirements of Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Microbiol. 13, 688–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ristroph J. D., Hedlund K. W., and Allen R. G. (1980) Liquid medium for growth of Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Microbiol. 11, 19–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ristroph J. D., Hedlund K. W., and Gowda S. (1981) Chemically defined medium for Legionella pneumophila growth. J. Clin. Microbiol. 13, 115–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wieland H., Ullrich S., Lang F., and Neumeister B. (2005) Intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila depends on host cell amino acid transporter SLC1A5. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 1528–1537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sauer J. D., Bachman M. A., and Swanson M. S. (2005) The phagosomal transporter A couples threonine acquisition to differentiation and replication of Legionella pneumophila in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 9924–9929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Price C. T., Al-Quadan T., Santic M., Rosenshine I., and Abu Kwaik Y. (2011) Host proteasomal degradation generates amino acids essential for intracellular bacterial growth. Science 334, 1553–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keen M. G., and Hoffman P. S. (1984) Metabolic pathways and nitrogen metabolism in Legionella pneumophila. Curr. Microbiol. 11, 81–88 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fonseca M. V., Sauer J.-D., and Swanson MS. (2008) Nutrient acquisition and assimilation strategies of Legionella pneumophila, in Legionella—Molecular Microbiology (Heuner K., and Swanson M. S., eds) pp. 213–226, Horizon Scientific Press, Norfolk, UK [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cazalet C., Rusniok C., Brüggemann H., Zidane N., Magnier A., Ma L., Tichit M., Jarraud S., Bouchier C., Vandenesch F., Kunst F., Etienne J., Glaser P., and Buchrieser C. (2004) Evidence in the Legionella pneumophila genome for exploitation of host cell functions and high genome plasticity. Nat. Genet. 36, 1165–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Harada E., Iida K., Shiota S., Nakayama H., and Yoshida S. (2010) Glucose metabolism in Legionella pneumophila: dependence on the Entner-Doudoroff pathway and connection with intracellular bacterial growth. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2892–2899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Herrmann V., Eidner A., Rydzewski K., Blädel I., Jules M., Buchrieser C., Eisenreich W., and Heuner K. (2011) GamA is a eukaryotic-like glucoamylase responsible for glycogen- and starch-degrading activity of Legionella pneumophila. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 301, 133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brzuszkiewicz E., Schulz T., Rydzewski K., Daniel R., Gillmaier N., Dittmann C., Holland G., Schunder E., Lautner M., Eisenreich W., Lück C., and Heuner K. (2013) Legionella oakridgensis ATCC 33761 genome sequence and phenotypic characterization reveals its replication capacity in amoebae. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303, 514–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heuner K., and Eisenreich W. (2016) Crosstalk between metabolism and virulence of Legionella pneumophila, in Host-Pathogen Interaction: Microbial Metabolism, Pathogenicity and Antiinfectives Part A: Adaptation of Microbial Metabolism in Host-Pathogen Interaction (Unden G., and Thines E., eds) Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, in press [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bertani G. (2004) Lysogeny at mid-twentieth century: P1, P2, and other experimental systems. J. Bacteriol. 186, 595–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bertani G. (1951) Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 62, 293–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lautner M., Schunder E., Herrmann V., and Heuner K. (2013) Regulation, integrase-dependent excision, and horizontal transfer of genomic islands in Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 195, 1583–1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sambrook J., Fritsch E.F., and Maniatis T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stone B. J., and Kwaik Y. A. (1999) Natural competence for DNA transformation by Legionella pneumophila and its association with expression of type IV pili. J. Bacteriol. 181, 1395–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schulz T., Rydzewski K., Schunder E., Holland G., Bannert N., and Heuner K. (2012) FliA expression analysis and influence of the regulatory proteins RpoN, FleQ and FliA on virulence and in vivo fitness in Legionella pneumophila. Arch. Microbiol. 194, 977–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee W. N., Byerley L. O., Bergner E. A., and Edmond J. (1991) Mass isotopomer analysis: theoretical and practical considerations. Biol. Mass Spectrom. 20, 451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Naumann D. (2008) FT-IR spectroscopy of microorganisms at the Robert Koch-Institute: experiences gained during a successful project. Proc. SPIE 6853, 68530G [Google Scholar]

- 46. Edwards R. L., Dalebroux Z. D., and Swanson M. S. (2009) Legionella pneumophila couples fatty acid flux to microbial differentiation and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 71, 1190–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Heuner K., Bender-Beck L., Brand B. C., Lück P. C., Mann K. H., Marre R., Ott M., and Hacker J. (1995) Cloning and genetic characterization of the flagellum subunit gene (flaA) of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. Infect. Immun. 63, 2499–2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aurass P., Pless B., Rydzewski K., Holland G., Bannert N., and Flieger A. (2009) bdhA-patD operon as a virulence determinant, revealed by a novel large-scale approach for identification of Legionella pneumophila mutants defective for amoeba infection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 4506–4515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Poirier Y. (2002) Polyhydroxyalknoate synthesis in plants as a tool for biotechnology and basic studies of lipid metabolism. Prog. Lipid Res. 41, 131–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ayub N. D., Julia Pettinari M., Méndez B. S., and López N. I. (2006) Impaired polyhydroxybutyrate biosynthesis from glucose in Pseudomonas sp. 14-3 is due to a defective β-ketothiolase gene. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 264, 125–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. O'Shaughnessy J. B., Chan M., Clark K., and Ivanetich K. M. (2003) Primer design for automated DNA sequencing in a core facility. BioTechniques 35, 112–121 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Molmeret M., Jones S., Santic M., Habyarimana F., Esteban M. T., and Kwaik Y. A. (2010) Temporal and spatial trigger of post-exponential virulence-associated regulatory cascades by Legionella pneumophila after bacterial escape into the host cell cytosol. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 704–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]