Abstract

The interaction of lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) with apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) plays a critical role in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) maturation. We previously identified a highly solvent-exposed apoA-I loop domain (Leu159–Leu170) in nascent HDL, the so-called “solar flare” (SF) region, and proposed that it serves as an LCAT docking site (Wu, Z., Wagner, M. A., Zheng, L., Parks, J. S., Shy, J. M., 3rd, Smith, J. D., Gogonea, V., and Hazen, S. L. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 861–868). The stability and role of the SF domain of apoA-I in supporting HDL binding and activation of LCAT are debated. Here we show by site-directed mutagenesis that multiple residues within the SF region (Pro165, Tyr166, Ser167, and Asp168) of apoA-I are critical for both LCAT binding to HDL and LCAT catalytic efficiency. The critical role for possible hydrogen bond interaction at apoA-I Tyr166 was further supported using reconstituted HDL generated from apoA-I mutants (Tyr166 → Glu or Asn), which showed preservation in both LCAT binding affinity and catalytic efficiency. Moreover, the in vivo functional significance of NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I, a specific post-translational modification on apoA-I that is abundant within human atherosclerotic plaque, was further investigated by using the recombinant protein generated from E. coli containing a mutated orthogonal tRNA synthetase/tRNACUA pair enabling site-specific insertion of the unnatural amino acid into apoA-I. NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I, after subcutaneous injection into hLCATTg/Tg, apoA-I−/− mice, showed impaired LCAT activation in vivo, with significant reduction in HDL cholesteryl ester formation. The present results thus identify multiple structural features within the solvent-exposed SF region of apoA-I of nascent HDL essential for optimal LCAT binding and catalytic efficiency.

Keywords: apolipoprotein, atherosclerosis, cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), post-translational modification (PTM), LCAT

Introduction

Apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I), the major protein component of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), transports lipids and also serves as a protein scaffold for numerous HDL-associated protein interactions. The HDL particle is responsible for facilitating reverse cholesterol transport, a multistep process that removes cholesterol from peripheral tissues and ultimately from the body in feces. To promote its cholesterol carrier functions, apoA-I exists in multiple forms throughout the reverse cholesterol transport process. Initially, lipid-free or lipid-poor apoA-I becomes lipidated, generating the nascent HDL particle via the ATP-binding cassette transporter type 1 (ABCA1)4 (1–4). Although capable of facilitating reverse cholesterol transport, subsequent maturation of the HDL particle into a cholesteryl ester-laden spherical particle substantially increases the capacity of the HDL particle to carry cholesterol cargo. Lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) is the primary enzyme responsible for catalyzing the maturation of nascent HDL into spherical HDL by catalyzing esterification of free cholesterol (1). Fielding and colleagues (5) first showed that apoA-I within nascent HDL stimulates LCAT activity (5–7). The mechanism by which LCAT facilitates HDL maturation at the structural level is still unknown.

Genetic studies confirm critical roles for both LCAT and apoA-I in lipid transport (8). Subjects with genetic deficiency of LCAT are characterized by markedly reduced HDL cholesterol levels (9). Whereas LCAT is clearly involved in the reverse cholesterol transport process and delivery of sterols to adrenal tissues, its role in atherosclerosis development is still debated (10–16). Naturally occurring mutations in human apoA-I that are associated with low LCAT activities and low levels of HDL cholesterol have been extensively reviewed (13, 17, 18). These naturally occurring mutations, along with a variety of site-specific mutation and deletion studies, have suggested that multiple regions on apoA-I are important for LCAT interactions with HDL (6–8, 19–23).

Using hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry analyses, we previously identified a peptide region (Leu159–Ala180) within apoA-I of nascent HDL with a markedly enhanced hydrogen-deuterium exchange rate, indicating a predominantly open and solvent-accessible conformation (24). A functional role for this region as an LCAT interaction site was suggested based upon additional hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry results, which showed reductions in deuterium incorporation rate within the overlapping apoA-I peptide region Leu159-Leu170 of nascent HDL in the presence versus absence of LCAT (24). We called this a “solar flare” (SF) region of apoA-I because it presumably represented a highly solvent-exposed protruding loop on the anti-parallel apoA-I chain in a nascent HDL particle (24). We reported that both point mutation of Tyr166 of apoA-I (i.e. Y166F), a residue that we showed is a target for oxidative post-translational modification within human atherosclerotic plaque (25, 26), and peptide competition assays, using a synthetic peptide whose sequence spans a portion of the SF region, further corroborated a role for this domain within apoA-I in LCAT interaction (24, 26). However, in contrast to our report that apoA-I Y166F affects LCAT activity by as much as 70% reduction (24), others reported a more minor (∼20%) reduction of LCAT activity of Y166F and questioned the significance of this residue and the SF region as a docking site for LCAT interaction (13). In more recent studies, we developed recombinant apoA-I with site-specific 3-nitrotyrosine incorporation only at position 166 of apoA-I using an evolved orthogonal nitro-Tyr-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNACUA pair. This enabled in vitro studies with recombinant human apoA-I incorporating this unnatural amino acid exclusively at position 166 to evaluate functional effects of NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I within reconstituted HDL and illustrated a reduced capacity to activate LCAT in vitro (26); however, the impact of this post-translational modification on LCAT-mediated maturation of HDL in vivo has not yet been explored.

There thus exists debate of the significance of the SF region of apoA-I for HDL/LCAT interaction, both as a docking site and in the activation of LCAT for particle maturation. We hypothesize that within the SF region of apoA-I, some of the amino acids are important for maintaining the structure of the loop and thus play a role in LCAT docking, whereas the same or others may impact presentation of the HDL particle lipid to LCAT, impacting catalytic activity. Herein we explore in detail critical structural and functional relationships within this proposed LCAT interaction loop of apoA-I to define the role(s) for individual amino acids in supporting both optimal LCAT binding to the nascent HDL particle and optimal LCAT catalytic efficiency. We also explore for the first time the in vivo functional impact of post-translational modification of apoA-I Tyr166 through nitration, which is enriched in human atherosclerotic lesions, using a humanized mouse model of apoA-I/LCAT interaction and infusion of endotoxin-free recombinant NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I.

Experimental Procedures

Materials and General Methods

All chemicals were from Sigma, and all solvents were HPLC grade unless otherwise indicated. [3H]cholesterol was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. The purity of recombinant apoA-I forms was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the purity and size of reconstituted HDL containing recombinant human apoA-I (rHDL) was estimated using both 4–20% non-denaturing equilibrium gel electrophoresis using precast gels (Bio-Rad) and dual-beam light scattering. The size of nascent HDL was determined by comparison with protein standards of known Stokes diameter (GE Healthcare). Cholesterol efflux (total and ABCA1-dependent) activity was measured using RAW264.7 cells in 48-well dishes according to established laboratory procedures (27). HDL cholesterol mass (both free and cholesteryl ester forms) were quantified using mass spectrometry as described previously (28). All mouse studies were performed under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Cleveland Clinic.

Mice

Transgenic human LCAT mice (hLCATTg/Tg) backcrossed onto a C57Bl/6J background (>10 generations) were provided by Dr. J. S. Parks and were described previously (10). ApoA-I knock-out mice (apoA-I−/−) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and have been backcrossed for >10 generations onto a C57Bl/6J background. Human LCAT Tg mice that are apoA-I-deficient (hLCATTg/Tg, apoA-I−/−) were generated by breeding hLCATTg/Tg mice on a C57Bl/6J background (>10 generations) with apoA-I−/− mice on a C57Bl/6J background (>10 generations).

Site-directed Mutagenesis and Expression of Recombinant and Mutant Forms of Human ApoA-I

Recombinant human apoA-I mutants carrying a single substitution (P165A, Y166X (where X represents Ala, Glu, Phe, or Asn), S167A, D168A, Y192F, or Y192L) were created by using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The template was the plasmid pET20b, containing the mature human apoA-I sequence, that had been codon-optimized for Escherichia coli expression as described previously (28). The QuikChange primers were designed by the online QuickChange Primer Design Program and further synthesized by IDT (Coralville, IA). The sequence of each mutated cDNA was verified by automated DNA sequence analysis before it was transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS for the expression of the recombinant proteins. Wild-type and mutant apoA-I forms were purified to homogeneity by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography as described (29). For studies where apoA-I was injected into mice for in vivo LCAT activity measurements, recombinant human apoA-I and NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I were generated as described previously (26) but using ClearColi® BL21(DE3), an E. coli strain genetically modified to be functionally deficient in generating endotoxin, as described recently for alternative apoA-I mutants (28). Endotoxin levels in all recombinant apoA-I were confirmed to be nominal (<0.5 EU/mg/ml protein) by a Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) under conditions where positive controls showed detection of trace levels of LPS (1.0 EU/mg/ml protein) added to apoA-I.

Preparation and Characterization of rHDL

rHDL containing the indicated recombinant apoA-I was prepared using the sodium cholate dialysis method (30), with a starting molar concentration ratio of 100:10:1 of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), free cholesterol, and apoA-I, respectively. All rHDL preparations were further purified using a Sephacryl-S300 column (GE Healthcare). Pooled fractions of rHDL were concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 10k centrifugal filter devices (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). The amounts of phospholipids and cholesterol in purified rHDL preparations were determined by a microphosphorus assay and a cholesterol enzymatic assay kit (Stanbio Laboratory, Boerne, TX), respectively, as described previously (31). The content of apoA-I within rHDL preparations was quantified by UV absorbance at A280 nm. Extinction coefficients used for WT and mutant apoA-I forms were individually calculated using the ProtParam tool, a program provided freely by the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. The ϵ280 used was 32,430 mol−1 cm−1 for WT apoA-I and the mutants P165A, S167A, and D168A and 30,940 mol−1 cm−1 for the apoA-I mutants Y166F, Y166A, Y166E, Y192F, and Y192L. Before use of UV spectroscopy for apoA-I quantification in all mutant apoA-I forms, the accuracy of this approach was verified (for WT and a few different mutant apoA-Is) by stable isotope dilution HPLC with on-line tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) by quantifying the amounts of leucine, tyrosine, and phenylalanine in apoA-I in acid hydrolysates using heavy isotope-labeled leucine, tyrosine, and phenylalanine as internal standards.

LCAT Kinetics Assay

Recombinant human LCAT (hLCAT) was purified from the culture medium of CHO cells transfected with hLCAT plasmid as described (32). The rHDL used as substrate for LCAT assay was prepared as described above but with the incorporation of a trace amount of [3H]cholesterol (45 Ci/mmol; GE Healthcare). The reaction mixtures contained 0–35 μm HDL cholesterol and 20 ng of purified His-tagged hLCAT in a buffer composed of 10 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 0.6% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin. Reactions were carried out in triplicate at 37 °C under argon. LCAT activity was determined by calculating the conversion efficiency of [3H]cholesterol into [3H]cholesteryl ester after lipid extraction of reaction mixture followed by thin layer chromatography and scintillation counting (24). The extent of cholesterol esterification was kept below 5% of free cholesterol levels to maintain first order kinetics. The fractional cholesterol esterification rate was expressed as nmol of cholesteryl ester formed/h/ng of LCAT. Apparent Vmax and Km values were determined from Hanes-Woolf plots of cholesterol substrate concentration divided by the cholesteryl ester formation rate versus HDL cholesterol substrate concentration using GraphPad Prism version 4 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

HDL/LCAT Binding Studies

Full time course kinetic determination of kon, koff, and apparent equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) for rHDL interaction with recombinant hLCAT were determined using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy (6). Measurements of apparent Kd between hLCAT and rHDL were performed using a BIAcore 3000 SPR biosensor (BIAcore, AB, Uppsala, Sweden) following the methods of Jin et al. (33) with modification. Briefly, ∼8000 relative units of polyclonal antibody against apoA-I (Biodesign, Saco, ME) was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip through primary amino groups using reactive esters as per the manufacturer's directions. rHDL was captured on the sensor chip through interaction with antibody against apoA-I by injecting 7 μm rHDL at a flow rate of 15 μl/min in 10 mm PBS buffer (pH 7.4) into the flow cell. To determine the Kd between rLCAT and rHDL, varying concentrations of recombinant hLCAT (500–2000 nm) were flowed over immobilized rHDL in binding buffer (10 mm PBS, pH 7.4) at a flow rate of 20 μl/min. Lipoprotein-depleted serum (5%, v/v) was used to reduce nonspecific binding when measuring HDL/LCAT binding affinities of NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I versus wild-type apoA-I. At the end of each cycle, surfaces of the sensor chips were regenerated by injection of 15 mm HCl at the same flow rate. The apparent Kd was obtained by fitting background-subtracted SPR binding data to the 1:1 binding with a drifting baseline model in BIAevaluation version 4.0 (BIAcore, AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

In Vivo LCAT Activity Measurement

Recombinant apoA-I proteins (NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I versus apoA-I (WT), 4 mg/animal) were injected subcutaneously into hLCATTg/Tg, apoA-I−/− mice, and serum samples were collected at the indicated time points. ApoB-containing lipoprotein fractions were precipitated, and then cholesterol and cholesteryl ester content of recovered HDL was quantified by stable isotope dilution gas chromatography with on-line mass spectrometry, as described previously (28).

Statistical Analyses

Statistically significant differences were determined by Student's t test. Statistical differences are reported when p was <0.05. All experimental results are presented as means ± S.D. of at least triplicate analyses.

Results

Characterization of Mutant ApoA-I and rHDL Particles

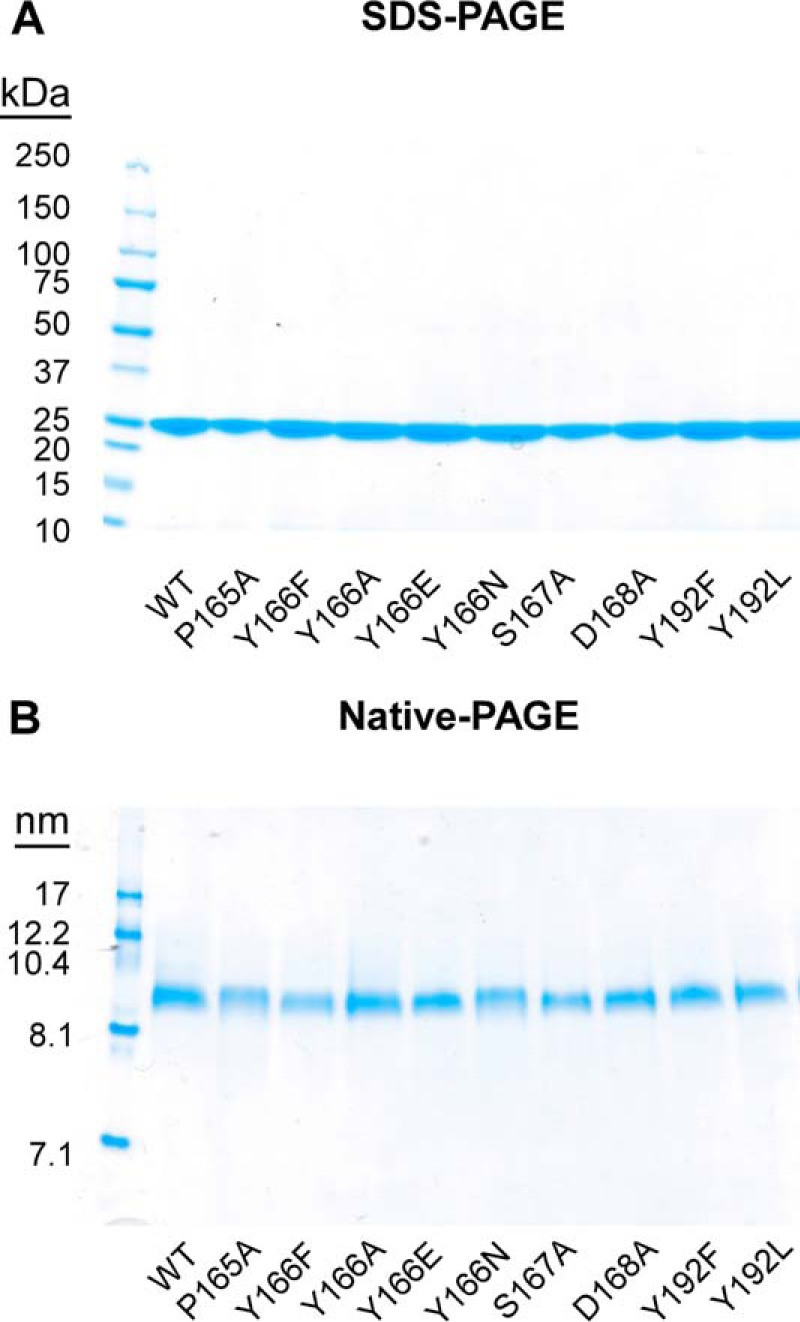

In addition to the wild type (WT) apoA-I protein, we initially generated a series of mutant recombinant human apoA-I forms (P165A, Y166F, S167A, and D168A) to investigate how these four adjacent amino acids within the SF region participate in LCAT interaction (docking and activation). Because of the controversy regarding whether Tyr166 of apoA-I serves as a functionally important residue in LCAT interaction (24, 34) and its involvement as a target for oxidative post-translational modification enriched in human atheroma (26, 35), we generated additional alternative mutations of this residue (Y166A, Y166E, and Y166N) to further investigate its unique potential role in LCAT docking and activation. Finally, we also mutated apoA-I Tyr192, an alternative target for oxidative post-translational modification enriched in human atheroma (35), to serve as a pathophysiologically relevant alternative residue that is presumed to be localized distant from the LCAT docking site. All apoA-I mutants were purified by nickel affinity chromatography to apparent homogeneity as judged by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A). To test the impact of mutation of these individual SF residues to HDL docking by LCAT, rHDLs were prepared containing each individual recombinant mutant apoA-I form. All rHDLs were prepared with a starting molar ratio of phospholipid (POPC)/cholesterol/apoA-I of 100:10:1, and then each rHDL was purified and characterized chemically and by native PAGE, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Analyses of rHDL incorporating individual apoA-I mutants demonstrated that each rHDL particle preparation was monodispersed, as determined by dual-beam light scattering, and ∼9.6 nm in diameter, as analyzed by 4–20% equilibrium native gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1B). The chemical compositions of the rHDL preparations were also remarkably similar, as shown in Table 1, with similar amounts of POPC and cholesterol, except for Y166F and D168A, which had slightly higher content of POPC within the HDL particles (25–30%). Analysis of the purified rHDL preparations by CD spectroscopy similarly shows no differences between WT and each of the mutant apoA-Is, indicating no significant change in their α-helical content. Thus, detailed chemical, sizing, and CD spectroscopy characterization suggested that the overall secondary structures of the WT versus mutant apoA-I forms within rHDL were similar.

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of recombinant apoA-I and reconstituted nascent HDL particles. Recombinant apoA-I (WT versus the indicated mutants) were purified from E. coli by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography, and nascent HDL particles were prepared using a modified cholate dialysis method at a molar ratio of 100:10:1 POPC/cholesterol/apoA-I. rHDL preparations were further purified using a Sephacryl-S300 size exclusion column. A, SDS-polyacrylamide gel analyses of purified recombinant apoA-I (WT and indicated point mutants). B, native polyacrylamide gel analyses of reconstituted nascent HDL containing recombinant WT apoA-I or the indicated point mutants.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of reconstituted nascent HDL particles

Reconstituted nascent HDL particles from the indicated recombinant apoA-I forms were prepared and isolated, and then the chemical composition of the particles was determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The size of nascent HDL particles was determined by comparison with the known diameter of globular standard proteins on equilibrium native PAGE analysis. Results represent mean ± S.D. of three independent HDL preparations.

| HDL | Molar ratio |

Diameter (native PAGE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POPC | Cholesterol | ApoA-I | ||

| nm | ||||

| WT | 89.3 ± 4.8 | 9.7 ± 0.5 | 1 | 9.6 |

| P165A | 107.7 ± 3.2 | 8.1 ± 0.1 | 1 | 9.6 |

| Y166F | 125.0 ± 4.4 | 7.8 ± 0.7 | 1 | 9.6 |

| S167A | 96.9 ± 0.7 | 7.1 ± 0.8 | 1 | 9.6 |

| D168A | 132.3 ± 2.6 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 1 | 9.6 |

| Y166A | 115.3 ± 3.9 | 9.8 ± 0.3 | 1 | 9.6 |

| Y166E | 82.1 ± 11.4 | 9.4 ± 0.2 | 1 | 9.6 |

| Y166N | 99.4 ± 3.2 | 8.5 ± 0.1 | 1 | 9.6 |

| Y192F | 105.6 ± 19.8 | 9.7 ± 0.3 | 1 | 9.6 |

| Y192L | 83.4 ± 6.7 | 10.4 ± 0.3 | 1 | 9.6 |

Mutations in the SF Region of ApoA-I Selectively Impact LCAT but Not Cholesterol Efflux Activity

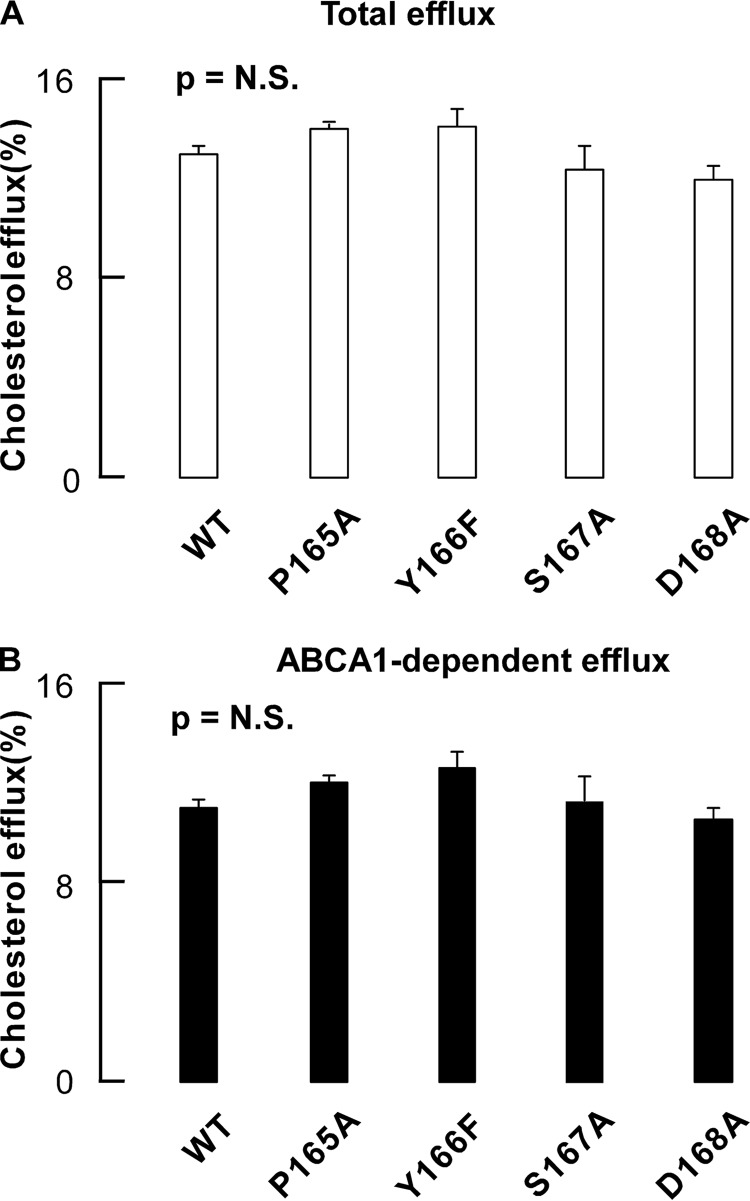

We first examined the effects of residues within the SF region of apoA-I on cholesterol efflux activity. Each lipid-free homogeneous apoA-I mutant (WT versus P165A, Y166F, S167A, and D168A) was individually incubated with cholesterol-loaded macrophages. As shown in Fig. 2, no apparent differences were observed in either total cholesterol efflux activity (under conditions of ABCA1 stimulation with 8-bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate) or ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux activity.

FIGURE 2.

Cholesterol efflux activities of nascent HDLs. A, total cholesterol efflux activities of recombinant apoA-I (WT, P165A, Y166F, S167A, and D168A) purified from E. coli. B, ABCA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux activities of recombinant apoA-I (WT, P165A, Y166F, S167A, and D168A) purified from E. coli. Cholesterol efflux activities were measured by incubating different HDL with RAW264.7 cells in 48-well dishes according to established procedures in the presence of ABCA1 stimulation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data shown represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of triplicate experiments. p values were nonsignificant (NS) as determined by Student's t test.

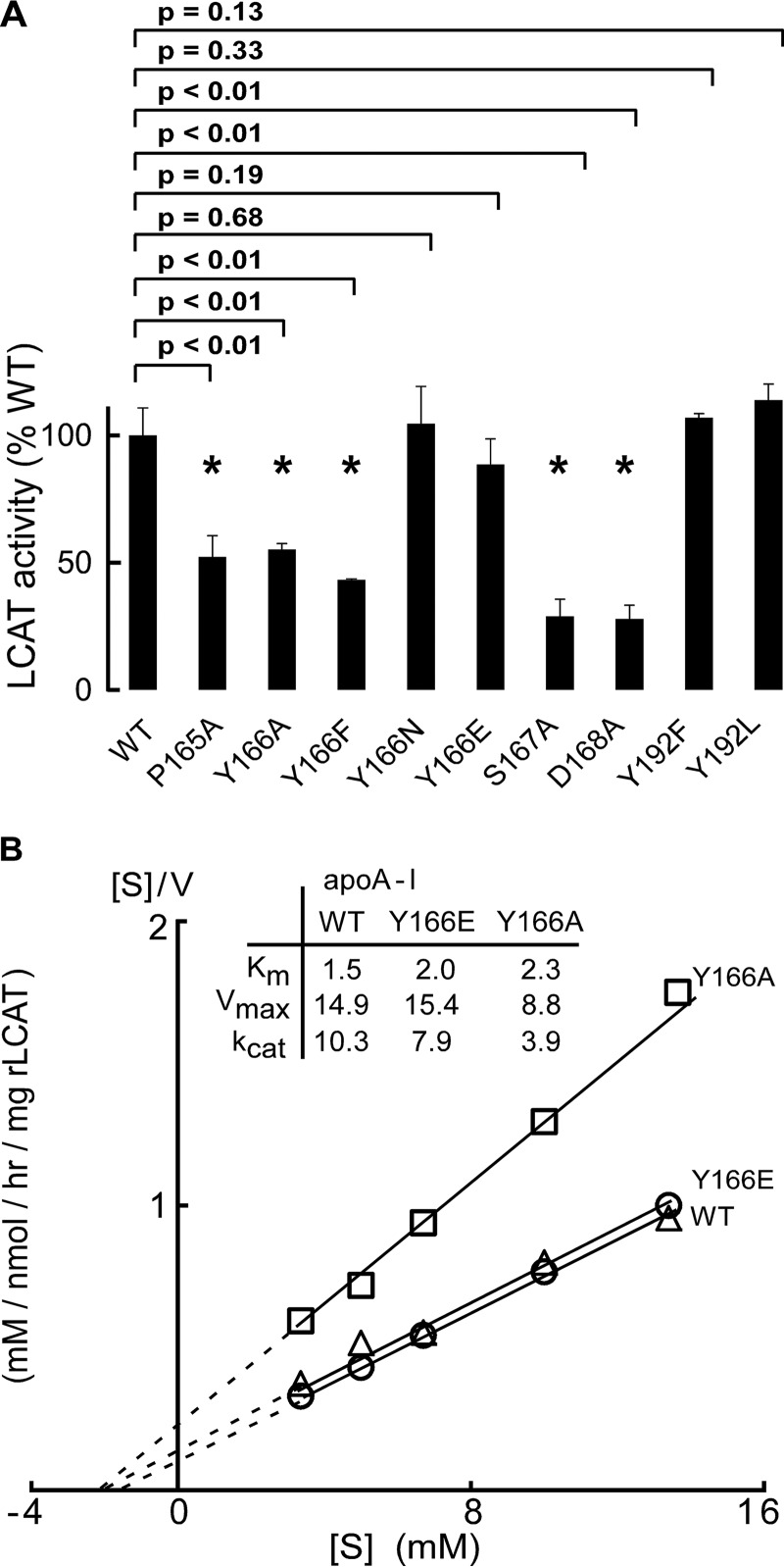

Next, LCAT activation properties of rHDL were characterized using the recombinant particles generated with either WT human apoA-I or the individual mutant apoA-I forms, including P165A, Y166X (where X represents Ala, Glu, Phe, or N), S167A, D168A, and Y192X (where X represents Phe or Leu). Incubation of hLCAT with rHDL formed using the apoA-I mutants P165A, Y166A, Y166F, S167A, and D168A all showed significant decreases in LCAT activity (40–60%; Fig. 3A) compared with WT. Interestingly, whereas the Y166A and Y166F apoA-I mutants showed suppressed LCAT activation activity, mutation of apoA-I Tyr166 to an amino acid residue capable of forming a hydrogen bond (e.g. Y166E and Y166N) fully restored LCAT activation capacity of rHDL particles produced with those apoA-I (relative to WT; Fig. 3). These studies thus affirm the importance of apoA-I Tyr166 in HDL for LCAT activation and suggest involvement of this residue in either a hydrogen bond or an ionic interaction with LCAT. In contrast to the importance of residues within the SF region, rHDL formed with either apoA-I Y192F or Y192L mutant showed normal LCAT activity (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

LCAT activities of nascent HDL. A, LCAT activities of reconstituted nascent HDL containing recombinant apoA-I (WT versus the different mutants indicated) were measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Note that Y166E/N and Y192F/L retain at least 80% of LCAT activities compared with WT, whereas P165A, Y166A/F, S167A, and D168A all exhibited significant reduction in the ability to activate LCAT compared with WT. B, Hanes-Woolf ([S]/V versus [S]) plots of nascent HDLs containing recombinant apoA-Is (WT, Y166A, and Y166E). Data shown represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of triplicate experiments. p values were determined by Student's t test.

To further evaluate the impact of each of the apoA-I mutants on LCAT catalytic efficiency, more detailed LCAT enzyme kinetics were performed. Table 2 shows the Km and Vmax for each of the rHDL formed with the indicated apoA-I mutants. Further, for illustrative purposes, Fig. 3B illustrates kinetic studies for WT apoA-I versus two of the Tyr166 mutant forms. Both Vmax of Y166F and Vmax of Y166A are 20% lower than that of WT apoA-I, and the apparent Km values are about 2–6-fold higher than that for WT (1.5 μm) (i.e. with a higher Km, the rHDLs harboring these mutant apoA-I are less effective at activating LCAT, and it takes a higher HDL concentration to achieve half-maximal LCAT activity). In contrast, replacement of Tyr166 with Glu or Asn only leads to slight changes of Km and Vmax. Replacement of apoA-I Asp168 with Ala also showed significant reduction of Km of LCAT (∼3-fold), whereas P165A and S167A showed a modest increase in Km. Besides the observed changes of Km of the rHDL incorporating these mutants, the reductions of Vmax were also observed with mutation to the Tyr166 and other SF sites. The Vmax values of mutants P165A, Y166A, Y166F, S167A, and D168A were all 30–60% lower than that of WT, whereas Y166E and Y166N had a Vmax similar to that of WT.

TABLE 2.

Reaction kinetics of recombinant nascent HDL particles with LCAT

Apparent kinetic parameters for the interaction of recombinant human LCAT and the indicated rHDL were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” All values represent the mean ± S.D. of results from three independent determinations.

| HDL | Apparent Km | Apparent Vmax | Apparent Vmax/Km | Percentage of WT kcat (Vmax/Km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | nmol/h/μg | nmol/h/μg/μm | % | |

| WT | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 14.9 ± 1.2 | 10.3 ± 1.4 | 100 |

| P165A | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 8.7 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 42 |

| Y166F | 10.0 ± 1.3 | 12.0 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 12 |

| Y166A | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 8.8 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 38 |

| Y166E | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 15.4 ± 1.8 | 7.9 ± 1.8 | 77 |

| Y166N | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 13.5 ± 2.0 | 9.4 ± 2.5 | 91 |

| S167A | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 5.6 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 29 |

| D168A | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 13 |

| Y192F | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 16.8 ± 0.5 | 7.2 ± 1.7 | 70 |

| Y192L | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 18.1 ± 0.9 | 8.9 ± 0.7 | 86 |

The overall catalytic efficiency (kcat) of LCAT-mediated conversion of cholesterol to cholesteryl ester can be estimated by the calculation of Vmax/Km. ApoA-I mutants P165A, Y166A, Y166F, S167A, and D168A only retained 12–42% of the catalytic efficiency of WT. Mutants Y166N and Y166E retained much higher LCAT catalytic efficiency (∼80%) compared with mutants Y166F and Y166A, which only retained 12–38% of LCAT catalytic efficiency.

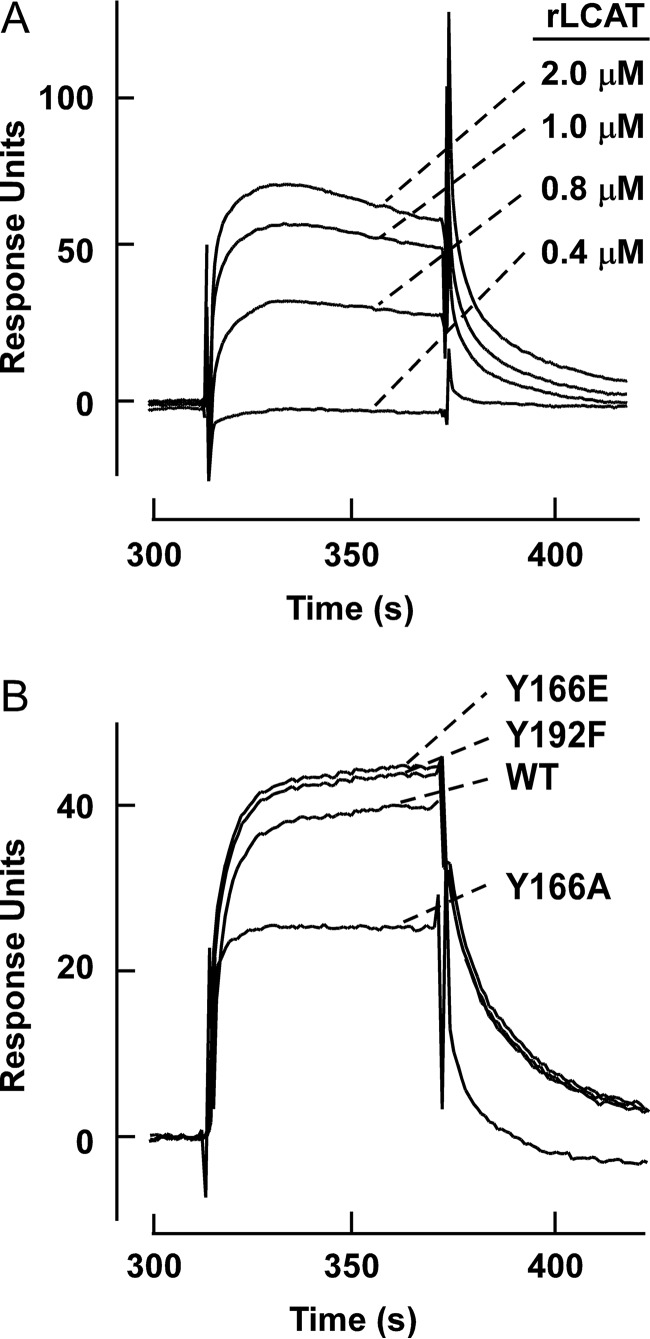

Mutations in the SF Region Impair HDL/LCAT Binding

To further probe the underlying mechanism of impairment of LCAT, catalytic efficiency caused by the mutations in the SF region of apoA-I, SPR analyses were performed to determine the Kd between hLCAT and rHDL formed with WT apoA-I versus each of the apoA-I mutant forms (Fig. 4). To eliminate the high background when HDLs were directly coated on the chips, rHDL harboring WT or mutant apoA-I were tethered to the chip by first coating the chip with goat anti-apoA-I antibody, coupling the indicated rHDL, and then varying concentrations of hLCAT flowed over the tethered rHDL. Results of the binding studies reaffirmed the generalization that apoA-I residues in the SF region are important for LCAT/HDL interaction (binding) (Table 3). Notably, we observed a direct correlation between the strength of LCAT/HDL binding and LCAT activation potential in the rHDL harboring each mutant. For example, apoA-I mutants Y166A, Y166F, and D168A, which showed ∼5-fold reduction in LCAT binding affinity, demonstrated the highest LCAT Km and the greatest reduction in LCAT catalytic efficiency. By comparison, apoA-I mutants P165A and S167A only exhibit 2–3-fold reduction in LCAT binding affinity and showed more modest elevation in Km and loss of LCAT catalytic efficiency. Interestingly, apoA-I mutants Y166E and Y166N, as well as both apoA-I Y192L and Y192F mutants, which do not show reduction in LCAT activation activity, also showed a Kd similar to that of WT apoA-I. The restoration of LCAT/HDL binding affinity and LCAT catalytic efficacy of apoA-I mutants Y166E and Y166N strongly suggests that the loss of LCAT activation caused by the apoA-I Y166A or Y166F mutation is at least partially due to the weaker binding between LCAT and apoA-I within these rHDLs.

FIGURE 4.

SPR sensorgrams of recombinant nascent HDL forms with LCAT. Goat anti-apoA-I antibody was first immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip. HDLs were captured on the sensor chip, and signals from a control flow cell and from buffer runs were subtracted. A, SPR sensorgrams of interaction between hLCAT and nascent HDL formed with recombinant WT apoA-I. The concentrations of LCAT are shown. B, differential LCAT binding to HDL made of either WT apoA-I or apoA-I Y166A, Y166E, or Y192F mutants.

TABLE 3.

Equilibrium constants of recombinant human LCAT binding to WT and mutant recombinant apoA-I HDLs using surface plasmon resonance spectrometry

Dissociation constants (Kd) of binding human LCAT to rHDL were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” All values represent the mean ± S.D. of triplicate determinations.

| HDL | Kd | WT binding affinity |

|---|---|---|

| μm | % | |

| WT | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 100 |

| P165A | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 36 |

| Y166F | 6.0 ± 0.8 | 23 |

| Y166A | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 22 |

| Y166E | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 109 |

| Y166N | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 140 |

| Y166YNO2 | 30.0 ± 0.7 | 5 |

| S167A | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 54 |

| D168A | 7.5 ± 1.0 | 19 |

| Y192F | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 100 |

NO2-Tyr166-ApoA-I Exhibits Impaired LCAT Activity in Vivo

Using a novel monoclonal antibody specific for NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I and not native apoA-I, we recently showed that post-translational modification of apoA-I through nitration of Tyr166 is remarkably abundant and is observed in 1 in 12 apoA-Is recovered from human atherosclerotic lesions, yet it is undetectable in normal aorta (26). We also developed recombinant apoA-I with site-specific 3-nitrotyrosine incorporation only at position 166 using an evolved orthogonal nitro-Tyr-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNACUA pair and showed that this abundant modified apoA-I has reduced capacity to activate LCAT in vitro when incorporated into rHDL (26). To further probe the underlying mechanism of impairment of LCAT catalytic efficiency caused by HDL harboring an apoA-I containing post-translational modification of Tyr166 by nitration, we performed surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy analyses. The Kd values for the interaction between hLCAT and rHDL formed with WT apoA-I versus NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I were examined. Nitration of apoA-I Tyr166 had a dramatic effect on HDL/hLCAT binding affinity, reducing the Kd of LCAT interaction with HDL generated from NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I by ∼20-fold compared with HDL from WT apoA-I (Table 3).

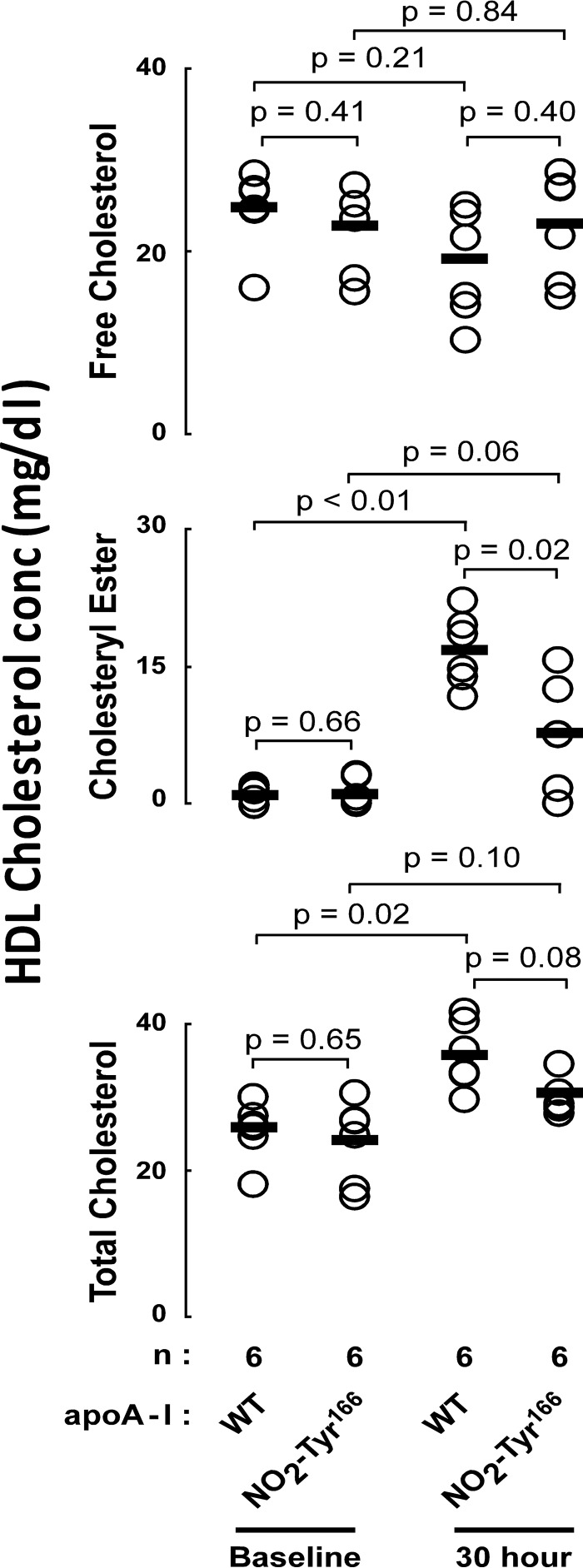

Collectively, the data show that apoA-I Tyr166 modification through nitration reduced the capacity to bind and activate LCAT in vitro. However, no in vivo investigations with recombinant NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I have thus far been performed. The reasons for this are severalfold. First, it has previously been reported that mouse LCAT does not interact with human apoA-I equivalently (36), and remarkably, Tyr166 is not conserved in mouse apoA-I. Thus, to adequately examine the function of NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I in vivo, we needed to develop a “humanized” model (i.e. human LCAT-containing) for investigation of this uniquely human apoA-I residue. Second, recombinant NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I initially produced in typical laboratory strains of E. coli contains endotoxin and is not suitable for in vivo studies. To overcome these obstacles in the present study, we (i) generated hLCATTg/Tg, apoA-I−/− mice, enabling studies of human apoA-I/LCAT interactions with injection of recombinant human apoA-I forms, and (ii) generated endotoxin-free recombinant human apoA-I forms using an E. coli strain genetically modified to be functionally deficient in synthesis of endotoxin, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Recombinant apoA-I proteins (NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I versus apoA-I WT) were injected subcutaneously into hLCATTg/Tg, apoA-I−/− mice, and at the indicated times, we quantified the HDL content of free cholesterol, total cholesterol, and cholesteryl ester levels, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” As shown in Fig. 5, no significant differences were observed in free cholesterol levels in HDL particles recovered at baseline versus following NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I or apoA-I WT injections. In contrast, both the cholesteryl ester and total cholesterol contents of HDL increased after recombinant apoA-I injections. More importantly, the cholesteryl ester level of recovered HDL particles, a measure of in vivo LCAT activity, showed significantly reduced increases after NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I injection compared with apoA-I WT injection (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

HDL cholesterol levels before versus after recombinant apoA-I injections. Plasma HDL free cholesterol (top), cholesteryl ester (middle), and total cholesterol (bottom) levels were quantified in human hLCATTg/Tg, apoA-I−/− mice before versus after subcutaneous injection of the indicated endotoxin-free recombinant apoA-I (WT versus NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I; 4 mg/animal). Serum samples were collected at the indicated time points. The LDL fraction was precipitated, and then cholesterol and cholesteryl ester content of HDL were quantified by stable isotope dilution gas chromatography with on-line mass spectrometry, as described previously (28). Data shown represent the mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments. p values were determined by Student's t test.

Discussion

We previously identified a highly solvent-exposed peptide region of apoA-I in nascent HDL using hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry and proposed that the region was a protruding loop or solar flare-like structure that served as an LCAT interaction site (24). However, the stability of the solar flare region was challenged in a later published brief computational study (37), and an alternative investigation reported that mutation of Tyr166, which is at the presumed tip of the protruding solar flare, produced only modest reduction of LCAT activity (13). Thus, the significance of both the solar flare region of apoA-I in general and Tyr166 specifically as an interaction site for LCAT docking and activation on the surface of nHDL has been questioned. The recognition of Tyr166 as an abundant post-translational modification to apoA-I within human atherosclerotic plaque (26, 35), however, makes investigation of the SF region of apoA-I in general and NO2-Tyr specifically of importance.

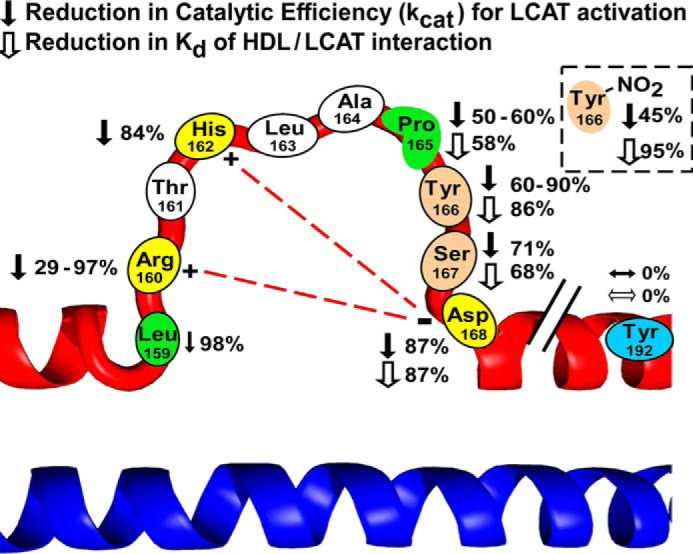

In the present study, we systematically examined the roles of individual amino acids in the SF loop region of apoA-I for their potential involvement in LCAT binding and activation. Table 4 and Fig. 6 summarize the overall impact of apoA-I mutations investigated in the present studies with respect to both LCAT binding to nHDL and the ability to activate LCAT. They also summarize proposed functional roles of the residues based on the results obtained. An overwhelming finding of the present studies is that site-specific mutation of multiple residues within the SF region of apoA-I markedly impairs both the binding of nHDL to LCAT and the ability of nHDL to activate LCAT. Moreover, mutation of the same residues in the SF region failed to adversely impact lipid binding (as judged by the comparable chemical compositions of rHDL formed) and cholesterol efflux activity of the apoA-I (as gauged by macrophage cholesterol efflux activity measurements in the presence and absence of ABCA1 stimulation).

TABLE 4.

Summary of the roles of amino acids in LCAT interaction loop of apoA-I

The presumed functions proposed for the apoA-I residues are speculative and are based on a combination of both site-specific mutagenesis/functional studies and structural models of apoA-I reported in nHDL.

| Amino acid in SF loop | Presumed function | Mutations/post-translational modification | Percentage of WT kcat (Vmax/Km) | Percentage of WT binding affinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | |||

| Leu159 | Structural | L159Ra | 2 | NDb |

| Arg160 | Salt bridge | R160La | 3–71 | ND |

| His162 | Salt bridge | H162Qa | 16 | ND |

| Pro165 | Structural | P165Ra | 38 | ND |

| P165A | 42 | 36 | ||

| Tyr166 | Hydrogen bond/polar interaction | Y166F | 12 | 23 |

| Y166E | 77 | 109 | ||

| Y166N | 91 | 140 | ||

| Y166A | 38 | 22 | ||

| Y166YNO2c | 55 | 5 | ||

| Ser167 | Hydrogen bond | S167A | 29 | 54 |

| Asp168 | Salt bridge | D168A | 13 | 19 |

FIGURE 6.

Schematic illustrating the amino acids in the solar flare region of apoA-I in HDL that affect LCAT activation and HDL/LCAT binding affinity. Shown is a schematic of a highly solvent-exposed loop domain of apoA-I, the so-called SF region, and mutations on each amino acid residue leading to reduction in the catalytic efficiency of LCAT activation (filled arrow) and HDL/LCAT binding affinity (open arrow). The post-translational modification at Tyr166 also reduced the catalytic efficiency of LCAT activation and HDL/LCAT binding affinity (box in the right corner). Previously proposed salt bridges between Arg160, His162, and Asp168 are shown with a red dashed line.

There are several amino acids in the SF region of apoA-I that are charged (Arg160, His162, Asp168, and Glu169) or bear a hydroxyl group (Thr161, Tyr166, and Ser167) that could potentially contribute to an ionic interaction or hydrogen bond for intra- or interprotein interactions critical to the HDL/LCAT reaction. Indeed, in modeling studies, we have suggested that Arg160, His162, and Asp168 may interact with one another through formation of a ternary salt bridge (24) (Fig. 6), providing the SF loop a measure of structural support, despite its proposed solvent-exposed extended conformation. Further, although mutations in apoA-I resulting in alterations in function are relatively rare, it is remarkable that naturally occurring mutations to some of these SF residues with associated reduction in LCAT activity have been reported. For example, subjects in families with either R160L (38) or H162Q (39) have been reported with low HDL cholesterol levels and reduced LCAT activation. Further, in one previous study of combined (double) apoA-I mutants replacing a pair of charged amino acids, both Arg160 and His162, with non-polar amino acids (R160V/H162A) produced an apoA-I form that showed a loss of LCAT activation similar to that of R160L and H162Q. Further, this double mutant similarly did not show significant change in secondary structure or lipid binding properties (40). Because we proposed the existence of salt bridges between the basic residues Arg160 and His162 with Asp168 in the loop region (Fig. 6) (24, 31), we expected that mutation in Asp168 would also significantly affect LCAT binding and activation (Table 4). Indeed, among all of the mutants produced and examined in this study, D168A exhibited the weakest LCAT binding affinity and the maximum loss of LCAT catalytic efficacy. The results of the D168A mutation are thus consistent with the existence of a proposed salt bridge in the SF loop region involving this residue. However, we think it fair to comment that we still cannot exclude the possibility that Asp168 may be important in HDL/LCAT interactions due to an alternative mechanism, such as through direct involvement in an ionic interaction with LCAT.

The present studies further extend our investigation of apoA-I Tyr166, a preferred site for myeloperoxidase- and nitric oxide-catalyzed oxidative modification that is abundant in human atherosclerotic plaque (25, 26). Because of prior conflicting results with the Y166F apoA-I mutant (34), in the present study, we not only performed more detailed enzyme kinetic analyses of Y166F but also examined in detail other mutants, including Y166A, Y166N, and Y166E, to more clearly define structure/function requirements for LCAT interaction with apoA-I Tyr166. rHDLs formed with either apoA-I mutant Y166A or Y166F each showed significant impairment in activating LCAT activity, with corresponding reductions in binding affinity for LCAT. Of interest, substitutions of Tyr166 with either Glu or Asn at this locus fully restored LCAT binding capacity and nearly restored (∼70%) LCAT catalytic activity. The observed LCAT binding and activation differences between WT and Y166A/E/F/N mutants suggest the possible existence of either ionic or hydrogen bond interaction of the phenoxyl hydrogen of apoA-I Tyr166 with LCAT. Importantly, our studies employing recombinant NO2-Tyr166-apoA-I show a 20-fold reduction in Kd with LCAT in vitro and, within the humanized model for studying apoA-I interaction with human LCAT (the hLCATTg/Tg, apoA-I−/− mouse), confirmed significant impairment in HDL maturation rate with this post-translational modification (Fig. 5).

Most of the mutations generated in this study are localized in the SF region of apoA-I and not in presumed regions of apoA-I linked to facilitating ABCA1 interaction, lipid binding, and cellular cholesterol efflux. It has been reported that apoA-I region 63–73 and the carboxyl end of apoA-I are important for lipid-free apoA-I-mediated cholesterol efflux, and the region 140–150 is important for ABCG1-mediated cholesterol efflux (41, 42). All of the apoA-I mutants examined in this study showed no significant impact on macrophage cholesterol efflux activity. Mutations in the loop region examined also did not affect the overall lipid composition of rHDL formed, suggesting that POPC and cholesterol binding properties of the mutants are similar to those of WT apoA-I (Table 1). The lack of changes in cholesterol efflux function and the similar CD spectra and predicted α-helicity of all of the mutants examined further support the contention that the overall secondary structures of apoA-I in nHDL are not affected by point mutations in the SF region. Indeed, our proposed structural models of apoA-I within nHDL predict that residues within the SF region are not in an α-helical but rather a loop conformation with stability provided by a pair of salt bridges with Asp168 (Fig. 6 and Table 4) (31, 43, 44). Because CD spectroscopy is sensitive to α-helical secondary structure but is insensitive to random coil or loop structure conformation, one would predict that mutations in the SF region would not significantly affect the overall α-helical content of apoA-I in nHDL as observed.

In conclusion, the data shown here are consistent with the SF region of apoA-I serving as an important LCAT docking site for nHDL that is also critical for appropriate lipid presentation and catalytic efficiency for LCAT-catalyzed cholesterol esterification. Moreover, in vivo studies using mice with humanized HDL/LCAT interaction and injection of endotoxin-free recombinant human apoA-I harboring site-specific incorporation of NO2-Tyr at position 166 confirm that this modified apoA-I form is dysfunctional, showing impaired LCAT-mediated HDL maturation in vivo. The present studies thus suggest that efforts to retard or block apoA-I modification at Tyr166 through either MPO- or nitric oxide-derived oxidants may have potential utility in preventing generation of a dysfunctional apoA-I or HDL form in vivo during atherosclerosis.

Author Contributions

X. G. and Z. W. both helped with design, performance, and analyses of all studies and the drafting of the manuscript. Y. H. assisted with plasmon resonance spectroscopy analyses. M. A. W., C. B.-G., A. J. D., and L. B. H. assisted with protein cloning, mutagenesis, and protein expression and purification. R. A. M., V. G., J. S. P., P. L. F., and J. A. D. assisted with study design and sharing of unique reagents. J. A. B. assisted with all in vivo studies. S. L. H. conceived of the project idea and assisted in design and analyses of experiments and the drafting of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P01 HL076491 and R01 HL119962 (to J. S. P.). S. L. H. is named as co-inventor on pending patents held by the Cleveland Clinic relating to cardiovascular and inflammation diagnostics. S. L. H. reports having been paid as a consultant for the following companies: Esperion and P&G. S. L. H. reports receiving research funds from Abbott, Astra Zeneca, P&G, Pfizer Inc., Roche, and Takeda. S. L. H. Hazen reports having the right to receive royalty payments for inventions or discoveries related to cardiovascular diagnostics or therapeutics from the following companies: Cleveland Heart Lab, Siemens, Esperion, Frantz Biomarkers, LLC. All other authors have no relationships to disclose. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- ABCA1

- ATP-binding cassette transporter type 1

- LCAT

- lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase

- SF

- solar flare

- rHDL

- reconstituted HDL containing recombinant human apoA-I

- POPC

- 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- hLCAT

- human LCAT

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- HDL

- high-density lipoprotein

- apoA-I

- apolipoprotein A-I

- kcat

- catalytic efficiency

- Kd

- equilibrium dissociation constant, Km, Michaelis constant

- Vmax

- maximum velocity

- LC/MS/MS

- HPLC with on-line tandem mass spectrometry

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary cells

- CD

- circular dicroism.

References

- 1. Glomset J. A. (1968) The plasma lecithins:cholesterol acyltransferase reaction. J. Lipid Res. 9, 155–167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brooks-Wilson A., Marcil M., Clee S. M., Zhang L. H., Roomp K., van Dam M., Yu L., Brewer C., Collins J. A., Molhuizen H. O., Loubser O., Ouelette B. F., Fichter K., Ashbourne-Excoffon K. J., Sensen C. W., Scherer S., Mott S., Denis M., Martindale D., Frohlich J., Morgan K., Koop B., Pimstone S., Kastelein J. J., Genest J. Jr., and Hayden M. R. (1999) Mutations in ABC1 in Tangier disease and familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency. Nat. Genet. 22, 336–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rust S., Rosier M., Funke H., Real J., Amoura Z., Piette J. C., Deleuze J. F., Brewer H. B., Duverger N., Denèfle P., and Assmann G. (1999) Tangier disease is caused by mutations in the gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1. Nat. Genet. 22, 352–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bodzioch M., Orsó E., Klucken J., Langmann T., Böttcher A., Diederich W., Drobnik W., Barlage S., Büchler C., Porsch-Ozcürümez M., Kaminski W. E., Hahmann H. W., Oette K., Rothe G., Aslanidis C., Lackner K. J., and Schmitz G. (1999) The gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 is mutated in Tangier disease. Nat. Genet. 22, 347–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fielding C. J., Shore V. G., and Fielding P. E. (1972) A protein cofactor of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 46, 1493–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cho K. H., Durbin D. M., and Jonas A. (2001) Role of individual amino acids of apolipoprotein A-I in the activation of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase and in HDL rearrangements. J. Lipid Res. 42, 379–389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alexander E. T., Bhat S., Thomas M. J., Weinberg R. B., Cook V. R., Bharadwaj M. S., and Sorci-Thomas M. (2005) Apolipoprotein A-I helix 6 negatively charged residues attenuate lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) reactivity. Biochemistry 44, 5409–5419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boes E., Coassin S., Kollerits B., Heid I. M., and Kronenberg F. (2009) Genetic-epidemiological evidence on genes associated with HDL cholesterol levels: a systematic in-depth review. Exp. Gerontol. 44, 136–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carlson L. A., and Philipson B. (1979) Fish-eye disease: a new familial condition with massive corneal opacities and dyslipoproteinaemia. Lancet 2, 922–924 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Furbee J. W. Jr., and Parks J. S. (2002) Transgenic overexpression of human lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) in mice does not increase aortic cholesterol deposition. Atherosclerosis 165, 89–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Furbee J. W. Jr., Sawyer J. K., and Parks J. S. (2002) Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency increases atherosclerosis in the low density lipoprotein receptor and apolipoprotein E knockout mice. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3511–3519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duivenvoorden R., Holleboom A. G., van den Bogaard B., Nederveen A. J., de Groot E., Hutten B. A., Schimmel A. W., Hovingh G. K., Kastelein J. J., Kuivenhoven J. A., and Stroes E. S. (2011) Carriers of lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase gene mutations have accelerated atherogenesis as assessed by carotid 3.0-T magnetic resonance imaging [corrected]. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 58, 2481–2487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kunnen S., and Van Eck M. (2012) Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase: old friend or foe in atherosclerosis? J. Lipid Res. 53, 1783–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van den Bogaard B., Holleboom A. G., Duivenvoorden R., Hutten B. A., Kastelein J. J., Hovingh G. K., Kuivenhoven J. A., Stroes E. S., and van den Born B. J. (2012) Patients with low HDL-cholesterol caused by mutations in LCAT have increased arterial stiffness. Atherosclerosis 225, 481–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bochem A. E., Holleboom A. G., Romijn J. A., Hoekstra M., Dallinga-Thie G. M., Motazacker M. M., Hovingh G. K., Kuivenhoven J. A., and Stroes E. S. (2013) High density lipoprotein as a source of cholesterol for adrenal steroidogenesis: a study in individuals with low plasma HDL-C. J. Lipid Res. 54, 1698–1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bochem A. E., Holleboom A. G., Romijn J. A., Hoekstra M., Dallinga G. M., Motazacker M. M., Hovingh G. K., Kuivenhoven J. A., and Stroes E. S. (2014) Adrenal Function in females with low plasma HDL-C due to mutations in ABCA1 and LCAT. PLoS One 9, e90967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schaefer E. J., Anthanont P., and Asztalos B. F. (2014) High-density lipoprotein metabolism, composition, function, and deficiency. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 25, 194–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saeedi R., Li M., and Frohlich J. (2015) A review on lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency. Clin. Biochem. 48, 472–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koukos G., Chroni A., Duka A., Kardassis D., and Zannis V. I. (2007) LCAT can rescue the abnormal phenotype produced by the natural ApoA-I mutations (Leu141Arg)Pisa and (Leu159Arg)FIN. Biochemistry 46, 10713–10721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sorci-Thomas M. G., Bhat S., and Thomas M. J. (2009) Activation of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase by HDL ApoA-I central helices. Clin. Lipidol. 4, 113–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roshan B., Ganda O. P., Desilva R., Ganim R. B., Ward E., Haessler S. D., Polisecki E. Y., Asztalos B. F., and Schaefer E. J. (2011) Homozygous lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) deficiency due to a new loss of function mutation and review of the literature. J. Clin. Lipidol. 5, 493–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fotakis P., Tiniakou I., Kateifides A. K., Gkolfinopoulou C., Chroni A., Stratikos E., Zannis V. I., and Kardassis D. (2013) Significance of the hydrophobic residues 225–230 of apoA-I for the biogenesis of HDL. J. Lipid Res. 54, 3293–3302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fotakis P., Kuivenhoven J. A., Dafnis E., Kardassis D., and Zannis V. I. (2015) The effect of natural LCAT mutations on the biogenesis of HDL. Biochemistry 54, 3348–3359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu Z., Wagner M. A., Zheng L., Parks J. S., Shy J. M. 3rd, Smith J. D., Gogonea V., and Hazen S. L. (2007) The refined structure of nascent HDL reveals a key functional domain for particle maturation and dysfunction. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 861–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zheng L., Settle M., Brubaker G., Schmitt D., Hazen S. L., Smith J. D., and Kinter M. (2005) Localization of nitration and chlorination sites on apolipoprotein A-I catalyzed by myeloperoxidase in human atheroma and associated oxidative impairment in ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux from macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. DiDonato J. A., Aulak K., Huang Y., Wagner M., Gerstenecker G., Topbas C., Gogonea V., DiDonato A. J., Tang W. H., Mehl R. A., Fox P. L., Plow E. F., Smith J. D., Fisher E. A., and Hazen S. L. (2014) Site-specific nitration of apolipoprotein A-I at tyrosine 166 is both abundant within human atherosclerotic plaque and dysfunctional. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 10276–10292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li X. M., Tang W. H., Mosior M. K., Huang Y., Wu Y., Matter W., Gao V., Schmitt D., Didonato J. A., Fisher E. A., Smith J. D., and Hazen S. L. (2013) Paradoxical association of enhanced cholesterol efflux with increased incident cardiovascular risks. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 1696–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang Y., DiDonato J. A., Levison B. S., Schmitt D., Li L., Wu Y., Buffa J., Kim T., Gerstenecker G. S., Gu X., Kadiyala C. S., Wang Z., Culley M. K., Hazen J. E., Didonato A. J., Fu X., Berisha S. Z., Peng D., Nguyen T. T., Liang S., Chuang C. C., Cho L., Plow E. F., Fox P. L., Gogonea V., Tang W. H., Parks J. S., Fisher E. A., Smith J. D., and Hazen S. L. (2014) An abundant dysfunctional apolipoprotein A1 in human atheroma. Nat. Med. 20, 193–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peng D. Q., Wu Z., Brubaker G., Zheng L., Settle M., Gross E., Kinter M., Hazen S. L., and Smith J. D. (2005) Tyrosine modification is not required for myeloperoxidase-induced loss of apolipoprotein A-I functional activities. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33775–33784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matz C. E., and Jonas A. (1982) Micellar complexes of human apolipoprotein A-I with phosphatidylcholines and cholesterol prepared from cholate-lipid dispersions. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 4535–4540 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wu Z., Gogonea V., Lee X., Wagner M. A., Li X. M., Huang Y., Undurti A., May R. P., Haertlein M., Moulin M., Gutsche I., Zaccai G., Didonato J. A., and Hazen S. L. (2009) Double superhelix model of high density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 36605–36619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chisholm J. W., Gebre A. K., and Parks J. S. (1999) Characterization of C-terminal histidine-tagged human recombinant lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase. J. Lipid Res. 40, 1512–1519 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jin L., Shieh J. J., Grabbe E., Adimoolam S., Durbin D., and Jonas A. (1999) Surface plasmon resonance biosensor studies of human wild-type and mutant lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase interactions with lipoproteins. Biochemistry 38, 15659–15665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shao B., Cavigiolio G., Brot N., Oda M. N., and Heinecke J. W. (2008) Methionine oxidation impairs reverse cholesterol transport by apolipoprotein A-I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12224–12229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zheng L., Nukuna B., Brennan M. L., Sun M., Goormastic M., Settle M., Schmitt D., Fu X., Thomson L., Fox P. L., Ischiropoulos H., Smith J. D., Kinter M., and Hazen S. L. (2004) Apolipoprotein A-I is a selective target for myeloperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation and functional impairment in subjects with cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 529–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Holvoet P., De Geest B., Van Linthout S., Lox M., Danloy S., Raes K., and Collen D. (2000) The Arg123–Tyr166 central domain of human ApoAI is critical for lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase-induced hyperalphalipoproteinemia and HDL remodeling in transgenic mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20, 459–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shih A. Y., Sligar S. G., and Schulten K. (2008) Molecular models need to be tested: the case of a solar flares discoidal HDL model. Biophys. J. 94, L87–L89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leren T. P., Bakken K. S., Daum U., Ose L., Berg K., Assmann G., and von Eckardstein A. (1997) Heterozygosity for apolipoprotein A-I(R160L)Oslo is associated with low levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol and HDL-subclass LpA-I/A-II but normal levels of HDL-subclass LpA-I. J. Lipid Res. 38, 121–131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hoang A., Huang W., Sasaki J., and Sviridov D. (2003) Natural mutations of apolipoprotein A-I impairing activation of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1631, 72–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gorshkova I. N., Liu T., Kan H. Y., Chroni A., Zannis V. I., and Atkinson D. (2006) Structure and stability of apolipoprotein A-I in solution and in discoidal high-density lipoprotein probed by double charge ablation and deletion mutation. Biochemistry 45, 1242–1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sviridov D., Pyle L. E., and Fidge N. (1996) Efflux of cellular cholesterol and phospholipid to apolipoprotein A-I mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 33277–33283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sviridov D., Hoang A., Huang W., and Sasaki J. (2002) Structure-function studies of apoA-I variants: site-directed mutagenesis and natural mutations. J. Lipid Res. 43, 1283–1292 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wu Z., Gogonea V., Lee X., May R. P., Pipich V., Wagner M. A., Undurti A., Tallant T. C., Baleanu-Gogonea C., Charlton F., Ioffe A., DiDonato J. A., Rye K. A., and Hazen S. L. (2011) The low resolution structure of ApoA1 in spherical high density lipoprotein revealed by small angle neutron scattering. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12495–12508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gogonea V., Gerstenecker G. S., Wu Z., Lee X., Topbas C., Wagner M. A., Tallant T. C., Smith J. D., Callow P., Pipich V., Malet H., Schoehn G., DiDonato J. A., and Hazen S. L. (2013) The low-resolution structure of nHDL reconstituted with DMPC with and without cholesterol reveals a mechanism for particle expansion. J. Lipid Res. 54, 966–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Miettinen H. E., Jauhiainen M., Gylling H., Ehnholm S., Palomäki A., Miettinen T. A., and Kontula K. (1997) Apolipoprotein A-IFIN (Leu159 → Arg) mutation affects lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase activation and subclass distribution of HDL but not cholesterol efflux from fibroblasts. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 17, 3021–3032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Daum U., Leren T. P., Langer C., Chirazi A., Cullen P., Pritchard P. H., Assmann G., and von Eckardstein A. (1999) Multiple dysfunctions of two apolipoprotein A-I variants, apoA-I(R160L)Oslo and apoA-I(P165R), that are associated with hypoalphalipoproteinemia in heterozygous carriers. J. Lipid Res. 40, 486–494 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]