Abstract

In this perspective, we highlight recent examples and trends in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology that demonstrate the synthetic potential of enzyme and pathway engineering for natural product discovery. In doing so, we introduce natural paradigms of secondary metabolism whereby simple carbon substrates are combined into complex molecules through “scaffold diversification”, and subsequent “derivatization” of these scaffolds is used to synthesize distinct complex natural products. We provide examples in which modern pathway engineering efforts including combinatorial biosynthesis and biological retrosynthesis can be coupled to directed enzyme evolution and rational enzyme engineering to allow access to the “privileged” chemical space of natural products in industry-proven microbes. Finally, we forecast the potential to produce natural product-like discovery platforms in biological systems that are amenable to single-step discovery, validation, and synthesis for streamlined discovery and production of biologically active agents.

Keywords: metabolic engineering, synthetic biology, natural product discovery

Introduction

Small molecules play an important role in enhancing our understanding of metabolic control in multistep reaction networks that underlie mechanisms of disease and orchestrate industrial biocatalysts. As such, small molecules account for a large fraction of the new drugs introduced each year, especially those emerging from natural products research. Metabolic probes and drug candidates are born from small molecule libraries that are typically limited in structural diversity, a key constraint for the discovery of new bioactive small molecules 1.

Organic chemists have boundless potential to create drugs with diverse molecular topologies from commodity chemicals using the immense diversity of reactions at their disposal. On the other hand, without selective pressures to guide the chemistry, practical discovery of biologically active agents is limited to the manipulation of known natural compounds and the use of combinatorial high-throughput screens 2. The de novo synthesis of complex natural products is a cost- and labor-intensive process, requiring world-class expertise. While traditional combinatorial chemistries employed orthogonal reactions to join small, flat, multi-functional building blocks, recent biology-inspired diversity-oriented methodologies are exploring a greater array of chemotypes with increased dimensionality and complexity, as one finds with natural secondary metabolites ( Figure 1) 1, 2. Unsurprisingly, chemically derived, biologically active compounds tend to resemble natural products. The similarities inform structural signatures of bioactivity, like the number of stereogenic carbons, scaffold rigidity, and the carbon/heteroatom ratio of the molecules 2, 3. Such descriptors of biological activity reveal that natural products provide a pool of “privileged” scaffolds as starting points for molecular probes and drugs 3. Combinatorial biosynthesis alleviates many of the concerns with traditional combinatorial chemistry by producing only those compounds with properties similar to natural products. In combinatorial biosynthesis, cells or enzymes are programed for diverse compound generation by systematically switching enzymes in a biosynthetic pathway (e.g. polyketide pathways) or using enzymes with broad substrate ranges (e.g. glycosyltransferases [GTs]) to produce product libraries ( Figure 1) 4– 6. Enzyme- and cell-based library generation emulates the natural means for creating chemical diversity by employing genetically encoded catalysts that co-evolve with their products in response to environmental pressures.

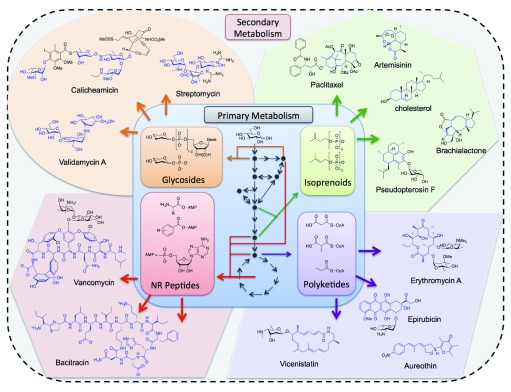

Figure 1. Schematic of natural diversity in secondary metabolism.

Complex metabolites diverge from a common pool of primary building blocks. Secondary metabolites and their respective precursors are grouped by colored areas: green (isoprenoids), purple (polyketides), red (non-ribosomal peptides), and orange (glycosides). Paradigmatic structures of each metabolite class are shown with the structure cores highlighted in blue. Colored arrows denote simplified enzymatic transformations. Black arrows and nodes correspond to central metabolism in heterotrophs to denote the origin of primary metabolites from central carbon.

Given immense recent interest in natural product biosynthesis and discovery 2, 7– 12, here we provide perspective on how synthetic biology and metabolic engineering are enabling compound discovery and biosynthesis. We parameterize natural themes for exploring chemical diversity under the guide of evolution. Finally, we forecast the potential for metabolic engineering to consolidate cell-based platforms for library generation and hit validation, as well as scalable synthesis in the practical discovery of biologically active compounds.

Engineering small molecule discovery platforms: derivatization vs. diversification

Advances in chemical biology and metabolic engineering are providing insights into the biological routes to create natural product diversity while also offering the potential to harness and manipulate this diversity under the guide of selective pressure. Armed with an arsenal of robust genetic tools and proven hosts for prokaryotic (e.g. Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Streptomyces sp.) and eukaryotic (e.g. Saccharomyces cerevisiae) production platforms, biological engineers have begun exploring diversity in both natural and unnatural contexts ( Figure 2) 13. Natural product diversity results from two themes of chemical evolution: derivatization of a shared molecular scaffold by variable functionalization of a common core, or diversification to enable the synthesis of various scaffold cores with distinct shapes from common building blocks ( Figure 2A). Below we describe recent trends and specific advances that highlight the importance of exploring chemical diversity in molecule discovery and underscore the role of synthetic biology and related fields towards this end.

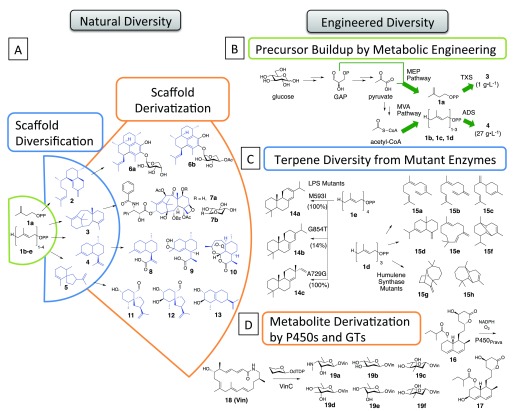

Figure 2. Natural paradigms for compound diversity inspire engineering efforts for compound discovery.

A) schematic of isoprenoid diversification in which distinct terpenes ( 2–5) arise from common building blocks ( 1a–e) and are subsequently functionalized into diverse isoprenoids ( 6–13); B) engineering secondary metabolite production requires augmented flux through biosynthetic pathways to access compound precursors, such as the buildup of isopentenyl diphosphate building blocks for the overproduction of taxadiene ( 3) 92 and amorphadiene ( 4) 93; C) scaffold diversification is emulated through enzyme engineering as shown in mutagenesis of the plant-derived levopimaradiene synthase (LPS) 79 and humulene synthase 88; D) scaffold derivatization is performed by engineered enzymes as in the P450-catalyzed hydroxylation of compactin ( 16) to produce the drug pravastatin ( 17), or by naturally promiscuous enzymes as with variable glycosylation of vicenilactam ( 18) with glycosyltransferase VinC 25, 36.

Diversity through scaffold derivatization

Chemical transformations of complex molecules often suffer from a lack of regioselectivity and stereoselectivity, poor discrimination between functional groups of similar reactivity, and an incompatibility with biological media. Enzymes, however, catalyze site-specific and stereoselective chemistries in water—often within a microorganism. Numerous enzyme-mediated chemical functionalizations of natural products are known, including scaffold alkylation 14– 16, acylation 17, oxidation 18, 19, glycosylation 4, 20, and halogenation 21. Here we focus the discussion of enzyme-tailored scaffold derivatization on the mature cases of natural product tailoring by cytochrome P450 oxidases (P450s or CYPs) and GTs. It is worth noting the biosynthetic potential of the lesser-utilized bio-acylation and bio-halogenation reactions for natural product derivatization, as these reactions can introduce orthogonally reactive handles for late-stage library differentiation 21.

A robust derivatization strategy employs naturally promiscuous P450s that have been engineered to harness multiple natural and novel chemistries in vivo 22– 24. For example, Keasling and co-workers used rational enzyme mutagenesis of a plant-mimicking bacterial enzyme (P450-BM3) capable of epoxidizing the plant-derived taxane amorpha-4,11-diene ( Figure 2 [ 4]) to obtain a more thermostable and selective epoxidation catalyst. P450-BM3 mutant G3A328L enabled the biosynthesis of the value-added compound artemisinic-11 S,12-epoxide at 250 mg/L in E. coli, thereby improving the semi-synthesis of the antimalarial drug artemisinin ( Figure 2 [ 10]) 18. Recently, McLean et al. evolved CYP105AS1 from Amycolatopsis orientalis to hydroxylate the pravastatin ( Figure 2 [ 17]) precursor compactin ( Figure 2 [ 16]) in the engineered Penicillium chrysogenum strain D550662, ultimately achieving titers of 6 g/L of the blockbuster drug after 200 h in a 10 L fed-batch fermentation ( Figure 2D) 25.

P450-catalyzed metabolite derivatization is likewise offering avenues to explore chemical space that was previously unavailable in a biological setting. Frances Arnold’s lab has developed an impressive array of P450 catalysts including an engineered diazoester-derived carbene transferase (P450 BM3/CYP102A1) for the stereoselective cyclopropanation of styrenes, which have concomitantly become available biologically via the metabolic engineering of E. coli for styrene production from L-phenylalanine at a titer of 260 mg/L 26, 27. Arnold’s team expanded the work to enable incorporation of the cyclopropane in vivo by engineering the electronics of the enzyme active site to accommodate NAD(P)H as an electron donor, and upon altering the active site architecture, they further engineered the catalyst for cyclopropanation of N,N-diethyl-2-phenylacrylamide, a putative intermediate in the formal synthesis of the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor levomilnacipran—marketed by Actavis Inc. as Fetzima for the treatment of clinical depression 28– 30. On the chemical front, Wallace and Balskus have developed porphyrin-iron(III) chloride catalysts that function similarly to Arnold’s P450-BM3 mutants while presenting biocompatible reactions with living styrene-producing E. coli 31. Such approaches highlight the potential to meld chemical and biological approaches for tailored molecule derivatization in engineered organisms 32, 33.

GTs are also attracting attention in the derivatization of natural products, including polyketides, non-ribosomal peptides, and terpenoids, for the discovery of novel antimicrobial agents with tailored pharmacological properties, including augmented target recognition and improved bio-availability 4, 20, 34, 35. In this regard, dNDP-glycosides ( Figure 1) represent a biosynthetically viable class of saccharide donors for promiscuous and engineered GTs that exhibit substrate tolerances for both the saccharide and aglycone portions of the reaction products. For instance, Minami et al. exploited the broad substrate tolerance of vicenisaminyltransferase VinC from Streptomyces halstedii HC 34 in the discovery of 22 novel glycosides from 50 sets of reactions for the glycodiversification of natural polyketide scaffolds ( Figure 2D) 36. More recently, Pandey et al. demonstrated the derivatization of clinically relevant resveratrol glycosides, producing ten different derivatives of the plant-derived metabolite, all accommodated by YjiC, a bacterial GT from Bacillus licheniformis 34, 37. However, in order for GT-catalyzed glyco-derivatization to be realized in vivo, the prerequisite biosynthesis of NDP-glycosides as glycosyl donors and acceptors must be engineered from bacterial monosaccharide and nucleotide triphosphate pools. A key advance in the supply of glycosyl donors was the discovery of the reversibility of GT-catalyzed reactions whereby Thorson and co-workers were able to generate more than 70 analogs of the natural products calicheamicin and vancomycin ( Figure 1) using various nucleotide sugars 38. Using OleD as the initial model enzyme, Thorson’s team evolved the substrate tolerance of GTs to enable glycosylation of not only natural products but also non-natural compounds and proteins 4, 39. More recently, Gantt et al. enabled the rapid, colorimetric screening of engineered GTs, and subsequently evolved an enzyme (OleD Loki) for the combinatorial enzymatic synthesis of 30 distinct NDP-sugars that are putatively amenable to further enzymatic manipulation in common microbial hosts 4, 40.

Metabolic engineering strategies for in vivo combinatorial glyco-derivatization of secondary metabolites have also demonstrated success by combining heterologous saccharide biosynthesis genes into non-natural pathways. In 1998, Madduri et al. demonstrated the fermentation of the antitumor drug epirubicin ( Figure 1) in Streptomyces peucetius and sparked intense interest in the role of metabolic engineering and combinatorial biosynthesis for the discovery and production of glyco-pharmaceuticals 20, 41– 44. These efforts have begun to impact glyco-engineering in more common microbial hosts, such as an in vivo small molecule “glyco-randomization” study in E. coli by Thorson and co-workers 4 or the variable derivatization of erythromycin by Pfeifer and co-workers 45; however, much success for in vivo glyco-derivatization remains in Streptomyces 4, 41, 46– 48.

Diversity through scaffold diversification

Scaffold derivatization enables the fine-tuning of compound activity by increasing compound resolution in a defined chemical space. The production of novel secondary metabolites through scaffold diversification, on the other hand, is a common theme of biosynthesis in plants and fungi that enables the exploration of completely new areas of chemical space. In order to generate beneficial molecules, it has been proposed that microbes and plants generate a diverse library of small molecules. Many liken these broad ranges of natural products to the host’s chemical “immune system”, where producing compounds with no known target could allow for resistance to an as-yet unencountered pathogen and provide evolutionary fitness of organisms with more diverse natural product portfolios 49– 51. Natural metabolite diversification has recently inspired diversity-oriented chemical syntheses that emulate the biological reaction cascades in the generation of new, drug-like scaffolds 1, 52, 53. Others have attempted to simplify metabolite archetypes to common core structures that may serve as starting points for discovery through derivatization; however, metabolite profiling of novel compounds from marine life and fungi continues to produce novel scaffold core structures, suggesting that to limit discovery to known scaffolds would severely curb the biosynthetic potential of evolutionary pressure 2, 54– 56. Engineering whole cells for scaffold diversification, on the other hand, was recently demonstrated by Wang et al., who combined the biosynthetic potential of plant, fungal, and bacterial enzymes for the production of 12 novel phenylpropanoid derivatives from L-tyrosine and L-phenylalanine in E. coli 57. Evolva reported the discovery of novel antiviral scaffolds using a heterologous flavonoid biosynthesis platform in S. cerevisiae 3, 58. By consolidating biosynthesis and screening into a single cell, the team was able to synthesize, validate, and structurally characterize 74 new compounds—28 of which showed activity in a secondary Brome Mosaic Virus assay—in less than nine months 3.

Aiding the discovery of new scaffolds, non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) and polyketide synthases (PKS) comprise equally useful, and often interconnected, classes of “assembly line” enzymes for in vivo scaffold diversification. The utility of NRPS/PKS enzymes for complex scaffold synthesis and elaboration emerges from the simplicity and modularity of their catalytic domains 59. Core NRPS/PKS genes encode for ketosynthase (KS), acyl transferase (AT), acyl/peptidyl carrier protein (ACP/PCP), condensation domain (C), and adenyltransferase (A) that catalyze the elongation of the polyketide/ peptide skeleton, and a terminal thioesterase (TE) severs the formed macrolide from the multi-domain synthetase. Along with auxiliary ketoreductase (KR), dehydratase (DH), and enoyl reductase (ER) domains, the core domains allow for the programmable building of variable macrolide and macrolactone scaffolds from divergent pools of ketoacids and amino acids 17, 59– 61. Once formed, the core scaffolds are natively derivatized by so-called “tailoring enzymes” to introduce native and non-native functionality as per the discussion of engineered P450s and GTs ( vide supra) 59.

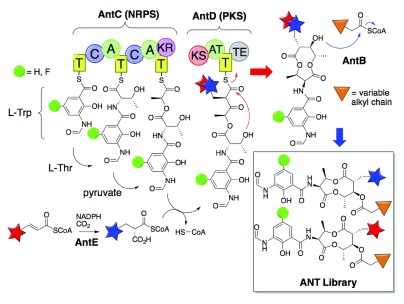

The modularity of the biosynthetic machinery of NRPS/PKS megasynthases allows for the rational engineering of combinatorial biosyntheses to access novel chemical space 7, 62. Combinatorial NRPS/PKS systems have enabled predictable changes to the scaffold core, derived from three programmable inputs into the biosynthesis. The inputs include the following: 1) variable use of organic building blocks such as short-chained acyl-coenzyme A (CoA) molecules or amino acids for the chain elongation step of scaffold synthesis 61, 63– 68; 2) chain length variations originating from KS and TE engineering 69– 70; and 3) alterations in the reduction program of the scaffold as a result of DH, KR, and ER engineering 71– 72. Yan et al. exemplified the biosynthetic potential to diversify antimycin (ANT) scaffolds through the metabolic engineering of promiscuous NRPS/PKS enzymes in the ANT-producing Streptomyces sp. NRRL 2288 ( Figure 3) 17. Following the in vivo production of ANT scaffolds with variable fluorination at C5’ and alkylation at C7, the authors further derivatized the ANT library at C8 with a promiscuous acylating protein (AntB) and various acyl-CoAs in vitro, generating 380 total and 356 novel ANT variants. Chemler et al. recently exploited the biosynthetic prowess of homologous recombination—a natural paradigm of NRPS/PKS evolution—to create PKS libraries for the programmable biosynthesis of engineered polyketide chimeras of known macrolide and macrolactone antibiotics pikromycin and erythromycin ( Figure 1) 60. Similarly, Sugimoto et al. demonstrated that engineering of an artificial PKS pathway by domain swapping in Streptomyces albus allowed reprogramming of the aureothin ( Figure 1) system for production of luteoreticulin and novel derivatives thereof 73. Despite significant challenges for NRPS/PKS engineering 5, 71, 74, recent successes with homologous recombination and structure-guided domain swapping of NRPS/PKS’s, coupled to the increased efficiency of Cas9-accelerated gene editing, forecast a time when functional NRPS/PKS variation may be routine 6, 60, 64, 66, 73, 75– 76.

Figure 3. Engineered diversification and derivatization of antimycin (ANT) scaffolds by a promiscuous PKS/NRPS (adapted from Yan et al., 2013) 17.

Domain key: T = thioylation (e.g. acyl/peptidyl carrier protein ACP/PCP), C = condensation, A = adenylation, KR = ketoreductase, KS = ketosynthase, AT = acyl transacylase, TE = thioesterase. Green ball represents variable use of H or F-modified starting material. Red vs. blue star depicts unsaturated and carboxylated acyl substituent at C7, respectively. Orange triangle depicts variation in the alkyl chain of the C8 acyl substituent.

Isoprenoids, enumerating over 55,000 compounds, comprise perhaps the richest source of diversity among secondary metabolites 77. The ability to emulate the natural evolution of this diversity will likely allow the access to known and new plant-derived isoprenoids ( Figure 2). Isoprenoid biosynthesis is characterized by four reactions of the five-carbon units isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP): chain elongation, branching, cyclopropanation, and cyclobutanation 77. Metabolic engineers have manipulated microbial pathways around the chain elongation reaction to build up terpenoid precursors of different lengths and stereochemistries, including IPP/DMAPP ( Figure 2 [ 1a–b]), geranyl diphosphate ( Figure 2 [ 1c]), farnesyl diphosphate ( Figure 2 [ 1d]), and others 78– 83. The strategy for introducing diversity as well as directing flux to a desired metabolite then comes from the subsequent pathway and enzyme engineering of terpene synthases that cyclize these building blocks, forming various scaffolds amenable to derivatization with downstream enzymes ( Figure 2C). A natural paradigm of terpene synthases and cyclases is the combination of substrate specificity with structural plasticity—a pairing of characteristics that enables rapid evolution of the enzyme for the production of product profiles that meet the environmental demands of the host organism 84. In support of this hypothesis, multiple groups have confirmed that through evolution and rational engineering, diterpene synthase activities can be altered to produce multiple, non-native terpenes ( Figure 2C) 9, 84– 88. Salmon et al. demonstrated that a convergent point mutation from a library of the Artemisia annua amorpha-4,11-diene synthase (Y420L) enabled the production of numerous cyclized products without compromising catalytic activity 89. Rising et al. discovered the serendipitous conversion of a non-natural substrate of tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase, anilinogeranyl diphosphate, to the novel paracyclophane terpene alkaloid 3,7-dimethyl-trans,trans-3,7-aza[9]paracyclophane-diene, which they dubbed “geraniline” 90. The finding demonstrates that terpene precursor diversity and bioavailability, in addition to terpene synthase engineering, are key inputs for programmable scaffold diversification. The explicit application of terpene diversification to diversity-oriented molecule discovery is gaining interest, but to realize the full biosynthetic potential of terpenes will likely require more insight into the mechanism of terpene synthases and the directed biosynthesis of terpene precursors 9, 91.

Engineering systems from discovery to production

Secondary metabolites are a treasure trove for the discovery of biologically active compounds, but they are metabolically “expensive”, leading organisms to match production to natural demands of the environment. To meet the demands for human need, microbial cells can be engineered to over-produce complex secondary metabolites—typically plant or fungal in origin—at the expense of host resources including energy storage molecules and biomass. High titers of non-native metabolites are possible via rational pathway engineering as shown in the case of taxadiene ( Figure 2 [ 3]) and amorpha-4,11-diene ( Figure 2 [ 4]) syntheses in E. coli, which detail that metabolite balance through modular pathways is crucial to high production ( Figure 2A) 92, 93. Bypassing regulation also allows increased production of native secondary metabolites, as shown recently by Tan et al. with validamycin ( Figure 1) biosynthesis in Streptomyces 94. The team generated a double deletion mutant ( S. hygroscopicus 5008 ∆shbR1/R3) to remove feedback inhibition and increase validamycin titers to 24 g/L and productivities to 9.7 g/L/d, which are the highest capacities yet reported 94.

Metabolic engineering can harvest synthetic genes from marine, plant, and fungal systems for the production of a diverse set of known compounds including terpenoids, flavonoids, and alkaloids in industrially useful microbial hosts 70, 95, 96. The reconstitution of heterologous pathways in fast-growing microbes is akin to hijacking evolution for efficient and expedient production. To this end, modular pathway reconstruction, or “retrobiosynthesis”, effectively maximizes a cell’s capacity to integrate new biological circuits and appropriate valuable cell resources for high secondary metabolite production 97– 99. Retrobiosynthesis allows for the systematic evaluation of complex multi-step pathways by isolating key transformations of a complete pathway into a series of independent modules that can be engineered in parallel 99. Leonard et al. demonstrated modular pathway engineering for the high-level production of levopimaradiene, a branch-point precursor to pharmaceutically relevant plant-derived ginkgolides 79. Upon increasing IPP/DMAPP titers through overexpression of mono-erythritol phosphate pathway enzymes in E. coli and separately engineering the geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase/levopimaradiene synthase system for increased selectivity and productivity, the team achieved a 700 mg/L titer in a bench-scale bioreactor. This is one of the first applications whereby metabolic engineering was combined with protein engineering to maximize production and selectivity of a desired compound.

Synthetic consortia offer another tool in which the metabolic burden of complex molecule synthesis can be distributed over multiple hosts. Recently, Zhou et al. engineered a cross-kingdom co-culture to produce oxygenated taxane precursors to the potent, plant-derived, anti-tumor drug paclitaxel ( Figure 1), achieving titers of 33 mg/L 100. Mimicking the general engineering strategy for spatially controlled production of branched-chain alcohols and mevalonate-derived terpenes in yeast 101, 102, Zhou et al. combined the divergent advantages of efficient cytochrome P450 expression in S. cerevisiae and the efficient taxadiene ( Figure 2 [ 3]) production in E. coli 92. The system emulates the native plant platform in which oxygen-sensitive taxadiene production is sequestered from the subsequent oxidations to form paclitaxel and other oxygenated taxanes in the peroxyzome 100, 102. The synthetic consortium put forth by Zhou et al. could represent a natural paradigm of plant isoprenoid production in plant-associated endophytes, further validating the general premise whereby metabolic engineering allows for the directed use of natural evolution for success in biosynthesis 103.

In the post-genomic era, gene mining for compound discovery is adding to the engineer’s toolbox. Hwang and others purport that multiplexed “omics” and bioinformatics enable the simultaneous identification of bacterial biosynthetic gene clusters, their encoded enzymes, and the structures of the resultant secondary metabolites for streamlined discovery of molecular structure and function 41, 104– 106. Systems-level analyses will further aid compound discovery by unveiling biosynthetic pathways of unknown secondary metabolites and antibiotics in actinomycetes and other organisms 107– 109. Of spectacular interest is the growing evidence for compound discovery by bioprospecting “unculturable” actinomycetes and uncharacterized bacteria by mapping, transforming, and editing their DNA heterologously in genetically tractable hosts with “out-of-the-box” genetic systems and clever metabolic engineering 110– 114.

Streamlined molecule discovery and production is likewise aided through the engineering of microbial systems for concomitant compound discovery, validation, and scale-up (e.g. the yeast discovery platform from Evolva; vide supra) 3. Recently, DeLoache et al. engineered S. cerevisiae to fluoresce orange in the presence of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA), an early intermediate en route to (S)-reticuline, and purple in the presence of L-dopaquinone, an unwanted byproduct of L-DOPA oxidation 115. PCR mutagenesis of a tyrosine P450 oxidase (CYP76AD1) produced a yeast library that could be easily screened by comparison of the orange:purple fluorescence of single cells with flow cytometry. The team identified P450 mutant CYP76AD1 W13L F309L as a selective catalyst for reduced L-DOPA production and continued to engineer a de novo pathway for (S)-reticuline production from glucose at titers of 80.6 µg/L. Albeit low titer, this approach has already been recognized for the ability to streamline microbial opioid production 116.

Conclusions

A reinvigoration of the potential for engineered enzymes and microorganisms to explore foreign biochemical space and discover molecular probes and therapeutics is clear from a number of recent commentaries and reviews 9, 11, 41, 117. Here, we describe examples from enzyme and pathway engineering to illustrate the successes, promises, and challenges for mining the plant, fungal, and microbial metabolomes to produce natural product-like molecules. We outline the underlying themes whereby nature explores chemical diversity through the diversification and derivatization of secondary metabolites—a robust strategy that has inspired recent diversity-oriented chemical syntheses. The co-evolution of natural products with their biosynthetic enzymes in response to environmental pressures is a theme whereby natural diversity begets evolutionary fitness. Several factors highlight the burgeoning potential of modern metabolic engineering to explore chemical diversity: 1) incredible investment into the genetic characterization of secondary metabolism over the last two decades has led to organization of natural product biosyntheses into standardized data sets 12, 118; 2) engineering promiscuous, biosynthetic enzymes has allowed for the DNA-encoded diversification of natural product libraries; 3) successful metabolic engineering of industrially proven microbes has allowed complex metabolite biosyntheses with high titers and productivities, and 4) recent technical advances for efficient homologous recombination and consolidated bioprospecting are allowing for biosynthetic compound library creation, validation, and scale-up with increasing simplicity. Perhaps a most critical advantage is that, once an active new structure is identified, through either scaffold derivatization or diversification in an engineered microbe, an actual biochemical process is also available for the synthesis of the target compound in substantial amounts required for toxicity and clinical trials. This path is more efficient compared to the many steps of a new chemical synthesis approach typically followed when promising compounds are identified from prospecting samples of natural sources. Broadly, the potential to apply metabolic engineering to access chemical diversity inspired by natural product biosynthesis illustrates an elegant pairing of science and engineering for biochemical progress.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

Jon S Thorson, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentuky, Lexington, KY, USA

Frances H Arnold, Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 1; referees: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Garcia-Castro M, Kremer L, Reinkemeier CD, et al. : De novo branching cascades for structural and functional diversity in small molecules. Nat Commun. 2015;6: 6516. 10.1038/ncomms7516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Hattum H, Waldmann H: Biology-oriented synthesis: harnessing the power of evolution. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(34):11853–9. 10.1021/ja505861d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klein J, Heal JR, Hamilton WD, et al. : Yeast synthetic biology platform generates novel chemical structures as scaffolds for drug discovery. ACS Synth Biol. 2014;3(5):314–23. 10.1021/sb400177x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 4. Gantt RW, Peltier-Pain P, Thorson JS: Enzymatic methods for glyco(diversification/randomization) of drugs and small molecules. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;28(11):1811–53. 10.1039/c1np00045d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 5. Wong FT, Khosla C: Combinatorial biosynthesis of polyketides--a perspective. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16(1–2):117–23. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu Y, Zhou T, Zhang S, et al. : Diversity-oriented combinatorial biosynthesis of benzenediol lactone scaffolds by subunit shuffling of fungal polyketide synthases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(34):12354–9. 10.1073/pnas.1406999111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhan N, Xu P, Koffas MA: Pathway and protein engineering approaches to produce novel and commodity small molecules. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24(6):1137–43. 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Breitling R, Takano E, Gardner TS: Judging synthetic biology risks. Science. 2015;347(6218):107. 10.1126/science.aaa5253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruck T, Kourist R, Loll B: Production of Macrocyclic Sesqui- and Diterpenes in Heterologous Microbial Hosts: A Systems Approach to Harness Nature's Molecular Diversity. Chemcatchem. 2014;6(5):1142–1165. 10.1002/cctc.201300733 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harvey AL, Edrada-Ebel R, Quinn RJ: The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14(2):111–29. 10.1038/nrd4510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim E, Moore BS, Yoon YJ: Reinvigorating natural product combinatorial biosynthesis with synthetic biology. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(9):649–59. 10.1038/nchembio.1893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 12. Medema MH, Fischbach MA: Computational approaches to natural product discovery. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(9):639–48. 10.1038/nchembio.1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang H, Boghigian BA, Armando J, et al. : Methods and options for the heterologous production of complex natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;28(1):125–51. 10.1039/c0np00037j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Singh S, Zhang J, Huber TD, et al. : Facile chemoenzymatic strategies for the synthesis and utilization of S-adenosyl-(L)-methionine analogues. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(15):3965–9. 10.1002/anie.201308272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Volgraf M, Gorostiza P, Numano R, et al. : Allosteric control of an ionotropic glutamate receptor with an optical switch. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(1):47–52. 10.1038/nchembio756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 16. Zhang C, Weller RL, Thorson JS, et al. : Natural product diversification using a non-natural cofactor analogue of S-adenosyl-L-methionine. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(9):2760–1. 10.1021/ja056231t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yan Y, Chen J, Zhang L, et al. : Multiplexing of combinatorial chemistry in antimycin biosynthesis: expansion of molecular diversity and utility. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52(47):12308–12. 10.1002/anie.201305569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 18. Dietrich JA, Yoshikuni Y, Fisher KJ, et al. : A novel semi-biosynthetic route for artemisinin production using engineered substrate-promiscuous P450 BM3. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4(4):261–7. 10.1021/cb900006h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 19. Fasan R: Tuning P450 Enzymes as Oxidation Catalysts. Acs Catal. 2012;2(4):647–666. 10.1021/cs300001x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhao LS, Liu HW: Pathway and Enzyme Engineering and Applications for Glycodiversification. Enzyme Technologies: Metagenomics, Evolution, Biocatalysis, and Biosynthesis. 2011;1:309–362. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown S, O'Connor SE: Halogenase Engineering for the Generation of New Natural Product Analogues. Chembiochem. 2015;16(15):2129–35. 10.1002/cbic.201500338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McIntosh JA, Farwell CC, Arnold FH: Expanding P450 catalytic reaction space through evolution and engineering. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2014;19:126–34. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Murphy CD: Drug metabolism in microorganisms. Biotechnol Lett. 2015;37(1):19–28. 10.1007/s10529-014-1653-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martinez CA, Rupashinghe SG: Cytochrome P450 bioreactors in the pharmaceutical industry: challenges and opportunities. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;13(12):1470–90. 10.2174/15680266113139990111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McLean KJ, Hans M, Meijrink B, et al. : Single-step fermentative production of the cholesterol-lowering drug pravastatin via reprogramming of Penicillium chrysogenum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(9):2847–52. 10.1073/pnas.1419028112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 26. Coelho PS, Brustad EM, Kannan A, et al. : Olefin cyclopropanation via carbene transfer catalyzed by engineered cytochrome P450 enzymes. Science. 2013;339(6117):307–10. 10.1126/science.1231434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 27. McKenna R, Nielsen DR: Styrene biosynthesis from glucose by engineered E. coli. Metab Eng. 2011;13(5):544–54. 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coelho PS, Wang ZJ, Ener ME, et al. : A serine-substituted P450 catalyzes highly efficient carbene transfer to olefins in vivo. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9(8):485–7. 10.1038/nchembio.1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 29. Heel T, McIntosh JA, Dodani SC, et al. : Non-natural olefin cyclopropanation catalyzed by diverse cytochrome P450s and other hemoproteins. Chembiochem. 2014;15(17):2556–62. 10.1002/cbic.201402286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 30. Wang ZJ, Renata H, Peck NE, et al. : Improved cyclopropanation activity of histidine-ligated cytochrome P450 enables the enantioselective formal synthesis of levomilnacipran. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(26):6810–3. 10.1002/anie.201402809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 31. Wallace S, Balskus EP: Interfacing microbial styrene production with a biocompatible cyclopropanation reaction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(24):7106–9. 10.1002/anie.201502185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 32. Köhler V, Turner NJ: Artificial concurrent catalytic processes involving enzymes. Chem Commun (Camb). 2015;51(3):450–64. 10.1039/c4cc07277d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wallace S, Balskus EP: Opportunities for merging chemical and biological synthesis. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2014;30:1–8. 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pandey RP, Parajuli P, Shin JY, et al. : Enzymatic Biosynthesis of Novel Resveratrol Glucoside and Glycoside Derivatives. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(23):7235–43. 10.1128/AEM.02076-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 35. Olano C, Méndez C, Salas JA: Harnessing Sugar Biosynthesis and Glycosylation to Redesign Natural Products and to Increase Structural Diversity. In Natural Products John Wiley & Sons, Inc.2014;317–339. 10.1002/9781118794623.ch17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Minami A, Eguchi T: Substrate flexibility of vicenisaminyltransferase VinC involved in the biosynthesis of vicenistatin. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(16):5102–7. 10.1021/ja0685250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 37. Patel KR, Scott E, Brown VA, et al. : Clinical trials of resveratrol. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1215:161–9. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05853.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang C, Griffith BR, Fu Q, et al. : Exploiting the reversibility of natural product glycosyltransferase-catalyzed reactions. Science. 2006;313(5791):1291–4. 10.1126/science.1130028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 39. Williams GJ, Zhang C, Thorson JS: Expanding the promiscuity of a natural-product glycosyltransferase by directed evolution. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(10):657–62. 10.1038/nchembio.2007.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gantt RW, Peltier-Pain P, Singh S, et al. : Broadening the scope of glycosyltransferase-catalyzed sugar nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(19):7648–53. 10.1073/pnas.1220220110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 41. Hwang KS, Kim HU, Charusanti P, et al. : Systems biology and biotechnology of Streptomyces species for the production of secondary metabolites. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32(2):255–68. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Madduri K, Kennedy J, Rivola G, et al. : Production of the antitumor drug epirubicin (4'-epidoxorubicin) and its precursor by a genetically engineered strain of Streptomyces peucetius. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16(1):69–74. 10.1038/nbt0198-69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 43. Murphy AC: Metabolic engineering is key to a sustainable chemical industry. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;28(8):1406–25. 10.1039/c1np00029b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pickens LB, Tang Y, Chooi YH: Metabolic engineering for the production of natural products. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2011;2:211–36. 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jiang M, Zhang H, Park SH, et al. : Deoxysugar pathway interchange for erythromycin analogues heterologously produced through Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2013;20:92–100. 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Han AR, Park JW, Lee MK, et al. : Development of a Streptomyces venezuelae-based combinatorial biosynthetic system for the production of glycosylated derivatives of doxorubicin and its biosynthetic intermediates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(14):4912–23. 10.1128/AEM.02527-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Williams GJ, Yang J, Zhang C, et al. : Recombinant E. coli prototype strains for in vivo glycorandomization. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6(1):95–100. 10.1021/cb100267k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yuan T, Xie L, Zhu B, et al. : Bioconversion of deoxysugar moieties to the biosynthetic intermediates of daunorubicin in an engineered strain of Streptomyces coeruleobidus. Biotechnol Lett. 2014;36(9):1809–18. 10.1007/s10529-014-1542-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Contreras-Cornejo HA, Macias-Rodriguez L, Herrera-Estrella A, et al. : The 4-phosphopantetheinyl transferase of Trichoderma virens plays a role in plant protection against Botrytis cinerea through volatile organic compound emission. Plant Soil. 2014;379(1):261–274. 10.1007/s11104-014-2069-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Iriti M, Faoro F: Chemical diversity and defence metabolism: how plants cope with pathogens and ozone pollution. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10(8):3371–99. 10.3390/ijms10083371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Keller NP: Translating biosynthetic gene clusters into fungal armor and weaponry. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(9):671–7. 10.1038/nchembio.1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Valot G, Garcia J, Duplan V, et al. : Diversity-oriented synthesis of diverse polycyclic scaffolds inspired by the logic of sesquiterpene lactones biosynthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(22):5391–4. 10.1002/anie.201201157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang J, Wu J, Hong B, et al. : Diversity-oriented synthesis of Lycopodium alkaloids inspired by the hidden functional group pairing pattern. Nat Commun. 2014;5: 4614. 10.1038/ncomms5614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li CS, Ding Y, Yang BJ, et al. : A New Metabolite with a Unique 4-Pyranone-γ-Lactam-1,4-Thiazine Moiety from a Hawaiian-Plant Associated Fungus. Org Lett. 2015;17(14):3556–9. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li C, Yang B, Fenstemacher R, et al. : Lycopodiellactone, an unusual delta-lactone-isochromanone from a Hawaiian plant-associated fungus Paraphaeosphaeria neglecta FT462. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56(13):1724–1727. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.02.076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rocha-Martin J, Harrington C, Dobson AD, et al. : Emerging strategies and integrated systems microbiology technologies for biodiscovery of marine bioactive compounds. Mar Drugs. 2014;12(6):3516–59. 10.3390/md12063516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang S, Zhang S, Xiao A, et al. : Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the biosynthesis of various phenylpropanoid derivatives. Metab Eng. 2015;29:153–9. 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 58. Naesby M, Nielsen SV, Nielsen CA, et al. : Yeast artificial chromosomes employed for random assembly of biosynthetic pathways and production of diverse compounds in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb Cell Fact. 2009;8:45. 10.1186/1475-2859-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 59. Fischbach MA, Walsh CT: Assembly-line enzymology for polyketide and nonribosomal Peptide antibiotics: logic, machinery, and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106(8):3468–96. 10.1021/cr0503097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chemler JA, Tripathi A, Hansen DA, et al. : Evolution of Efficient Modular Polyketide Synthases by Homologous Recombination. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(33):10603–9. 10.1021/jacs.5b04842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 61. Walker MC, Thuronyi BW, Charkoudian LK, et al. : Expanding the fluorine chemistry of living systems using engineered polyketide synthase pathways. Science. 2013;341(6150):1089–94. 10.1126/science.1242345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 62. Moss SJ, Martin CJ, Wilkinson B: Loss of co-linearity by modular polyketide synthases: a mechanism for the evolution of chemical diversity. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21(5):575–93. 10.1039/b315020h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bravo-Rodriguez K, Ismail-Ali AF, Klopries S, et al. : Predicted incorporation of non-native substrates by a polyketide synthase yields bioactive natural product derivatives. Chembiochem. 2014;15(13):1991–7. 10.1002/cbic.201402206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Crusemann M, Kohlhaas C, Piel J: Evolution-guided engineering of nonribosomal peptide synthetase adenylation domains. Chem Sci. 2013;4:1041–1045. 10.1039/C2SC21722H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dunn BJ, Cane DE, Khosla C: Mechanism and specificity of an acyltransferase domain from a modular polyketide synthase. Biochemistry. 2013;52(11):1839–41. 10.1021/bi400185v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kries H, Wachtel R, Pabst A, et al. : Reprogramming nonribosomal peptide synthetases for "clickable" amino acids. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(38):10105–8. 10.1002/anie.201405281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Thirlway J, Lewis R, Nunns L, et al. : Introduction of a non-natural amino acid into a nonribosomal peptide antibiotic by modification of adenylation domain specificity. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(29):7181–4. 10.1002/anie.201202043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yan J, Hazzard C, Bonnett SA, et al. : Functional modular dissection of DEBS1-TE changes triketide lactone ratios and provides insight into Acyl group loading, hydrolysis, and ACP transfer. Biochemistry. 2012;51(46):9333–41. 10.1021/bi300830q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Liu T, Sanchez JF, Chiang YM, et al. : Rational domain swaps reveal insights about chain length control by ketosynthase domains in fungal nonreducing polyketide synthases. Org Lett. 2014;16(6):1676–9. 10.1021/ol5003384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhou Y, Prediger P, Dias LC, et al. : Macrodiolide formation by the thioesterase of a modular polyketide synthase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(17):5232–5. 10.1002/anie.201500401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cane DE: Programming of erythromycin biosynthesis by a modular polyketide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(36):27517–23. 10.1074/jbc.R110.144618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. He HY, Yuan H, Tang MC, et al. : An unusual dehydratase acting on glycerate and a ketoreducatse stereoselectively reducing α-ketone in polyketide starter unit biosynthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(42):11315–9. 10.1002/anie.201406602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 73. Sugimoto Y, Ding L, Ishida K, et al. : Rational design of modular polyketide synthases: morphing the aureothin pathway into a luteoreticulin assembly line. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(6):1560–4. 10.1002/anie.201308176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 74. Tang GL, Cheng YQ, Shen B: Leinamycin biosynthesis revealing unprecedented architectural complexity for a hybrid polyketide synthase and nonribosomal peptide synthetase. Chem Biol. 2004;11(1):33–45. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Dutta S, Whicher JR, Hansen DA, et al. : Structure of a modular polyketide synthase. Nature. 2014;510(7506):512–7. 10.1038/nature13423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 76. Jiang Y, Chen B, Duan C, et al. : Multigene editing in the Escherichia coli genome via the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(7):2506–14. 10.1128/AEM.04023-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Thulasiram HV, Erickson HK, Poulter CD: Chimeras of two isoprenoid synthases catalyze all four coupling reactions in isoprenoid biosynthesis. Science. 2007;316(5821):73–6. 10.1126/science.1137786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 78. Carlsen S, Ajikumar PK, Formenti LR, et al. : Heterologous expression and characterization of bacterial 2- C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(13):5753–69. 10.1007/s00253-013-4877-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Leonard E, Ajikumar PK, Thayer K, et al. : Combining metabolic and protein engineering of a terpenoid biosynthetic pathway for overproduction and selectivity control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(31):13654–9. 10.1073/pnas.1006138107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Martin VJ, Pitera DJ, Withers ST, et al. : Engineering a mevalonate pathway in Escherichia coli for production of terpenoids. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(7):796–802. 10.1038/nbt833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 81. Morrone D, Lowry L, Determan MK, et al. : Increasing diterpene yield with a modular metabolic engineering system in E. coli: comparison of MEV and MEP isoprenoid precursor pathway engineering. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85(6):1893–906. 10.1007/s00253-009-2219-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wang C, Zhou J, Jang HJ, et al. : Engineered heterologous FPP synthases-mediated Z, E-FPP synthesis in E. coli. Metab Eng. 2013;18:53–9. 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zhu S, Wu J, Du G, et al. : Efficient synthesis of eriodictyol from L-tyrosine in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(10):3072–80. 10.1128/AEM.03986-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kampranis SC, Ioannidis D, Purvis A, et al. : Rational conversion of substrate and product specificity in a Salvia monoterpene synthase: structural insights into the evolution of terpene synthase function. Plant Cell. 2007;19(6):1994–2005. 10.1105/tpc.106.047779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Gonzalez V, Touchet S, Grundy DJ, et al. : Evolutionary and mechanistic insights from the reconstruction of α-humulene synthases from a modern (+)-germacrene A synthase. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(41):14505–12. 10.1021/ja5066366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Gorner C, Hauslein I, Schrepfer P, et al. : Targeted Engineering of Cyclooctat-9-en-7-ol Synthase: A Stereospecific Access to Two New Non-natural Fusicoccane-Type Diterpenes. Chemcatchem. 2013;5(11):3289–3298. 10.1002/cctc.201300285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Morrone D, Xu M, Fulton DB, et al. : Increasing complexity of a diterpene synthase reaction with a single residue switch. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(16):5400–1. 10.1021/ja710524w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yoshikuni Y, Ferrin TE, Keasling JD: Designed divergent evolution of enzyme function. Nature. 2006;440(7087):1078–82. 10.1038/nature04607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 89. Salmon M, Laurendon C, Vardakou M, et al. : Emergence of terpene cyclization in Artemisia annua. Nat Commun. 2015;6: 6143. 10.1038/ncomms7143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 90. Rising KA, Crenshaw CM, Koo HJ, et al. : Formation of a Novel Macrocyclic Alkaloid from the Unnatural Farnesyl Diphosphate Analogue Anilinogeranyl Diphosphate by 5-Epi-Aristolochene Synthase. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(7):1729–36. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 91. Zerbe P, Bohlmann J: Plant diterpene synthases: exploring modularity and metabolic diversity for bioengineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2015;33(7):419–28. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ajikumar PK, Xiao WH, Tyo KE, et al. : Isoprenoid pathway optimization for Taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science. 2010;330(6000):70–4. 10.1126/science.1191652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 93. Tsuruta H, Paddon CJ, Eng D, et al. : High-level production of amorpha-4,11-diene, a precursor of the antimalarial agent artemisinin, in Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2009;4(2):e4489. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Tan GY, Peng Y, Lu C, et al. : Engineering validamycin production by tandem deletion of γ-butyrolactone receptor genes in Streptomyces hygroscopicus 5008. Metab Eng. 2015;28:74–81. 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 95. Brown S, Clastre M, Courdavault V, et al. : De novo production of the plant-derived alkaloid strictosidine in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(11):3205–10. 10.1073/pnas.1423555112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Trantas EA, Koffas MA, Xu P, et al. : When plants produce not enough or at all: metabolic engineering of flavonoids in microbial hosts. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:7. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ajikumar PK, Tyo K, Carlsen S, et al. : Terpenoids: opportunities for biosynthesis of natural product drugs using engineered microorganisms. Mol Pharm. 2008;5(2):167–90. 10.1021/mp700151b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Dugar D, Stephanopoulos G: Relative potential of biosynthetic pathways for biofuels and bio-based products. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(12):1074–8. 10.1038/nbt.2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Prather KL, Martin CH: De novo biosynthetic pathways: rational design of microbial chemical factories. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19(5):468–74. 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zhou K, Qiao K, Edgar S, et al. : Distributing a metabolic pathway among a microbial consortium enhances production of natural products. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(4):377–83. 10.1038/nbt.3095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Avalos JL, Fink GR, Stephanopoulos G: Compartmentalization of metabolic pathways in yeast mitochondria improves the production of branched-chain alcohols. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(4):335–41. 10.1038/nbt.2509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Farhi M, Marhevka E, Masci T, et al. : Harnessing yeast subcellular compartments for the production of plant terpenoids. Metab Eng. 2011;13(5):474–81. 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kusari S, Pandey SP, Spiteller M: Untapped mutualistic paradigms linking host plant and endophytic fungal production of similar bioactive secondary metabolites. Phytochemistry. 2013;91:81–7. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Chooi YH, Solomon PS: A chemical ecogenomics approach to understand the roles of secondary metabolites in fungal cereal pathogens. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:640. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hofberger JA, Ramirez AM, Bergh Ev, et al. : Large-Scale Evolutionary Analysis of Genes and Supergene Clusters from Terpenoid Modular Pathways Provides Insights into Metabolic Diversification in Flowering Plants. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128808. 10.1371/journal.pone.0128808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Yadav VG, De Mey M, Lim CG, et al. : The future of metabolic engineering and synthetic biology: towards a systematic practice. Metab Eng. 2012;14(3):233–41. 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Annadurai RS, Neethiraj R, Jayakumar V, et al. : De Novo transcriptome assembly (NGS) of Curcuma longa L. rhizome reveals novel transcripts related to anticancer and antimalarial terpenoids. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Guo F, Xiang S, Li L, et al. : Targeted activation of silent natural product biosynthesis pathways by reporter-guided mutant selection. Metab Eng. 2015;28:134–42. 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Rutledge PJ, Challis GL: Discovery of microbial natural products by activation of silent biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(8):509–23. 10.1038/nrmicro3496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Gaida SM, Sandoval NR, Nicolaou SA, et al. : Expression of heterologous sigma factors enables functional screening of metagenomic and heterologous genomic libraries. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7045. 10.1038/ncomms8045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 111. Kushwaha M, Salis HM: A portable expression resource for engineering cross-species genetic circuits and pathways. Nat Commun. 2015;6: 7832. 10.1038/ncomms8832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 112. Owen JG, Charlop-Powers Z, Smith AG, et al. : Multiplexed metagenome mining using short DNA sequence tags facilitates targeted discovery of epoxyketone proteasome inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(14):4221–6. 10.1073/pnas.1501124112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 113. Owen JG, Reddy BV, Ternei MA, et al. : Mapping gene clusters within arrayed metagenomic libraries to expand the structural diversity of biomedically relevant natural products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(29):11797–802. 10.1073/pnas.1222159110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 114. Yamanaka K, Reynolds KA, Kersten RD, et al. : Direct cloning and refactoring of a silent lipopeptide biosynthetic gene cluster yields the antibiotic taromycin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(5):1957–62. 10.1073/pnas.1319584111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 115. DeLoache WC, Russ ZN, Narcross L, et al. : An enzyme-coupled biosensor enables ( S)-reticuline production in yeast from glucose. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(7):465–71. 10.1038/nchembio.1816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 116. Ehrenberg R: Engineered yeast paves way for home-brew heroin. Nature. 2015;521(7552):267–8. 10.1038/251267a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Sun H, Liu Z, Zhao H, et al. : Recent advances in combinatorial biosynthesis for drug discovery. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:823–33. 10.2147/DDDT.S63023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Medema MH, Kottmann R, Yilmaz P, et al. : Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(9):625–31. 10.1038/nchembio.1890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation