Abstract

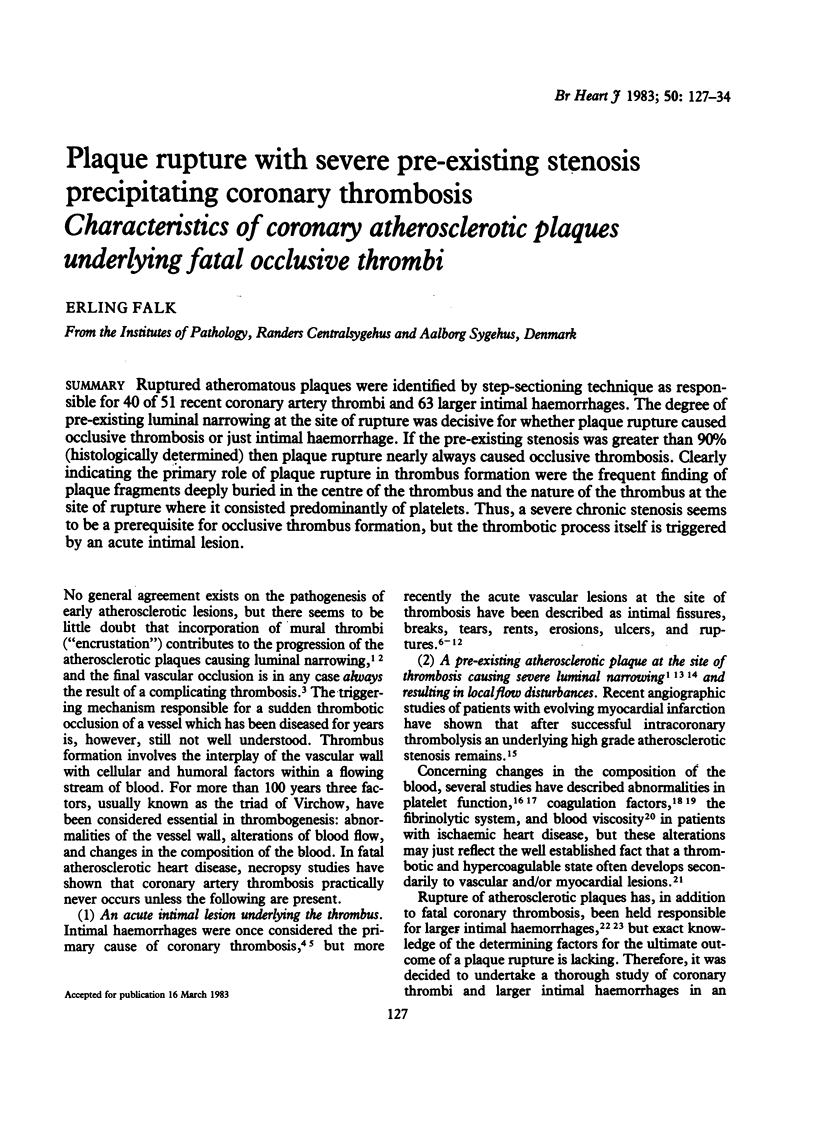

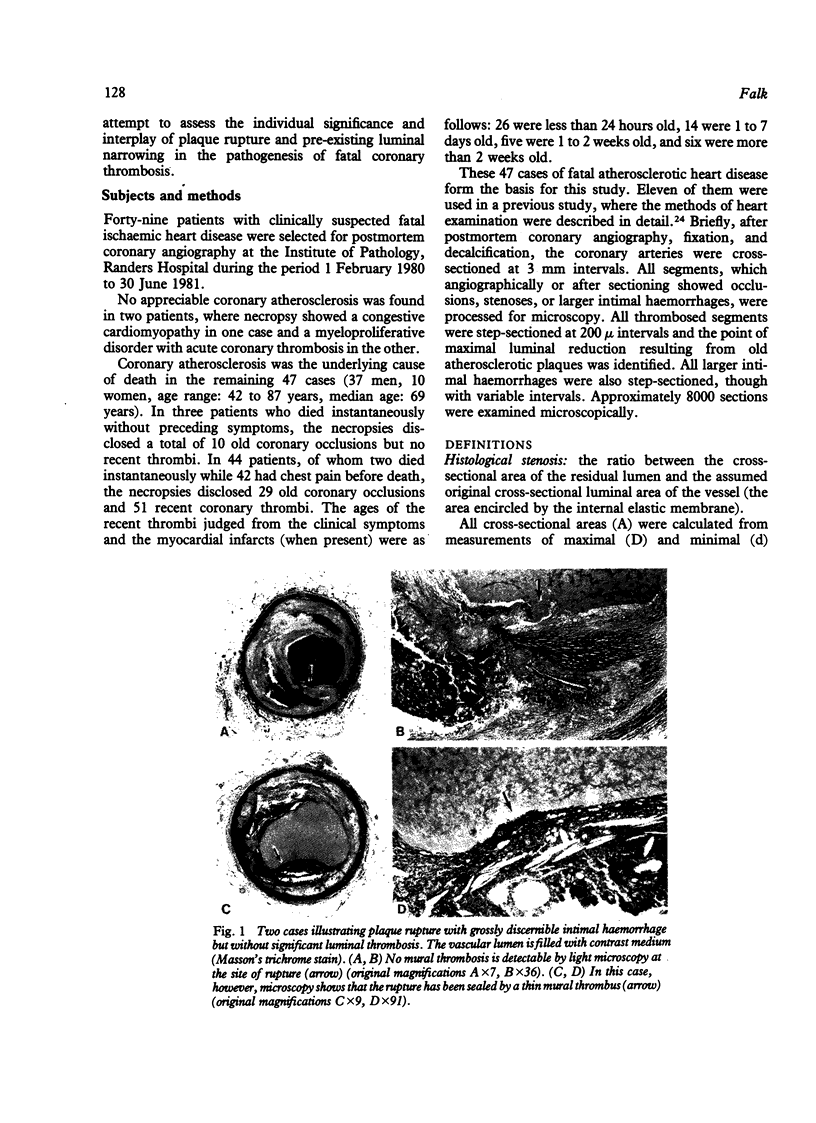

Ruptured atheromatous plaques were identified by step-sectioning technique as responsible for 40 of 51 recent coronary artery thrombi and 63 larger intimal haemorrhages. The degree of pre-existing luminal narrowing at the site of rupture was decisive for whether plaque rupture caused occlusive thrombosis or just intimal haemorrhage. If the pre-existing stenosis was greater than 90% (histologically determined) then plaque rupture nearly always caused occlusive thrombosis. Clearly indicating the primary role of plaque rupture in thrombus formation were the frequent finding of plaque fragments deeply buried in the centre of the thrombus and the nature of the thrombus at the site of rupture where it consisted predominantly of platelets. Thus, a severe chronic stenosis seems to be a prerequisite for occlusive thrombus formation, but the thrombotic process itself is triggered by an acute intimal lesion.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arkin C. F., Hartman A. S. The hypercoagulability states. CRC Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1979;10(4):397–429. doi: 10.3109/10408367909147139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAPMAN I. MORPHOGENESIS OF OCCLUDING CORONARY ARTERY THROMBOSIS. Arch Pathol. 1965 Sep;80:256–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRAWFORD T., DEXTER D., TEARE R. D. Coronary-artery pathology in sudden death from myocardial ischaemia. A comparison by age-groups. Lancet. 1961 Jan 28;1(7170):181–185. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(61)91363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M. J., Fulton W. F., Robertson W. B. The relation of coronary thrombosis to ischaemic myocardial necrosis. J Pathol. 1979 Feb;127(2):99–110. doi: 10.1002/path.1711270208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M. J., Thomas T. The pathological basis and microanatomy of occlusive thrombus formation in human coronary arteries. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1981 Aug 18;294(1072):225–229. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1981.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWood M. A., Spores J., Notske R., Mouser L. T., Burroughs R., Golden M. S., Lang H. T. Prevalence of total coronary occlusion during the early hours of transmural myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1980 Oct 16;303(16):897–902. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010163031601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk E. Coronary artery narrowing without irreversible myocardial damage or development of collaterals. Assessment of "critical" stenosis in a human model. Br Heart J. 1982 Sep;48(3):265–271. doi: 10.1136/hrt.48.3.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folts J. D., Gallagher K., Rowe G. G. Blood flow reductions in stenosed canine coronary arteries: vasospasm or platelet aggregation? Circulation. 1982 Feb;65(2):248–255. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.65.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M., Van den Bovenkamp G. J. The pathogenesis of a coronary thrombus. Am J Pathol. 1966 Jan;48(1):19–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M., Van den Bovenkamp G. The pathogenesis of coronary intramural haemorrhages. Br J Exp Pathol. 1966 Aug;47(4):347–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton J. R., Gorlin R. Platelet studies in patients with coronary artery disease and in their relatives. Br Heart J. 1972 May;34(5):465–471. doi: 10.1136/hrt.34.5.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom H. R. Evidence in favor of the vasospastic cause of coronary artery thrombosis. Am Heart J. 1979 Apr;97(4):449–452. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(79)90391-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie T., Sekiguchi M., Hirosawa K. Coronary thrombosis in pathogenesis of acute myocardial infarction. Histopathological study of coronary arteries in 108 necropsied cases using serial section. Br Heart J. 1978 Feb;40(2):153–161. doi: 10.1136/hrt.40.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostis J. B., Baughman D. J., Kuo P. T. Association of recurrent myocardial infarction with hemostatic factors: a prospective study. Chest. 1982 May;81(5):571–575. doi: 10.1378/chest.81.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe G. D., McArdle B. M., Stromberg P., Lorimer A. R., Forbes C. D., Prentice C. R. Increased blood viscosity and fibrinolytic inhibitor in type II hyperlipoproteinaemia. Lancet. 1982 Feb 27;1(8270):472–475. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentrop P., Blanke H., Karsch K. R., Kaiser H., Köstering H., Leitz K. Selective intracoronary thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina pectoris. Circulation. 1981 Feb;63(2):307–317. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridolfi R. L., Hutchins G. M. The relationship between coronary artery lesions and myocardial infarcts: ulceration of atherosclerotic plaques precipitating coronary thrombosis. Am Heart J. 1977 Apr;93(4):468–486. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(77)80410-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinapius D. Beziehungen zwischen Koronarthrombosen und Myokardinfarkten. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1972 Mar 24;97(12):443–448. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1107374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinapius D. Uber Wandveränderungen bei Coronarthrombose. Bemerkungen zur Haufigkeit, Entstehung und Bedeutung. Klin Wochenschr. 1965 Aug 15;43(16):875–880. doi: 10.1007/BF01711252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K. K., Hoak J. C. Spontaneous platelet aggregation in arterial insufficiency: mechanisms and implications. Thromb Haemost. 1976 Jun 30;35(3):702–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]