Abstract

IgM nephropathy is a relatively rare cause of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome.1 It was initially described by van de Putte,2 then by Cohen and Bhasin in 1978, as a distinctive feature of mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis.2 It is typically characterized by diffuse IgM deposits on the glomeruli and diffuse mesangial hypercellularity. Little is known about the pathogenesis and treatment of this disease.1,3 We describe a patient who presented with nonspecific symptoms of epigastric pain, nausea, and early satiety. Abdominal imaging and endoscopies were unremarkable. She was found to have significant proteinuria (6.4 g/24 hours), hyperlipidemia, and edema consistent with a diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome. Kidney biopsy was performed and confirmed an IgM nephropathy. Less than 2 weeks after her diagnosis of IgM nephropathy, she presented with an acute cerebellar stroke. Thrombophilia is a well-known complication of nephrotic syndrome, but a review of the literature failed to show an association between IgM nephropathy and acute central nervous system thrombosis.

Keywords: IgM nephropathy, thromboembolic events, cerebellar thrombosis

A. Adike, M.D.

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and hypothyroidism presented with a 2-month history of epigastric pain associated with abdominal distention, nausea, and generalized malaise. She also noted facial and bilateral leg swelling. Despite reporting decreased appetite, she had gained approximately 20 pounds in 1 month. She denied hematuria, fevers, night sweats, joint pain, vomiting, diarrhea, or changes in stool color or caliber. Admission vital signs were within normal range. Physical examination was remarkable for a mildly distended abdomen without evidence of ascites or peritoneal signs. Her lungs were clear and she had no jugular venous distention. There was 3+ pretibial pitting edema in her lower extremities bilaterally. Periorbital edema was also noted.

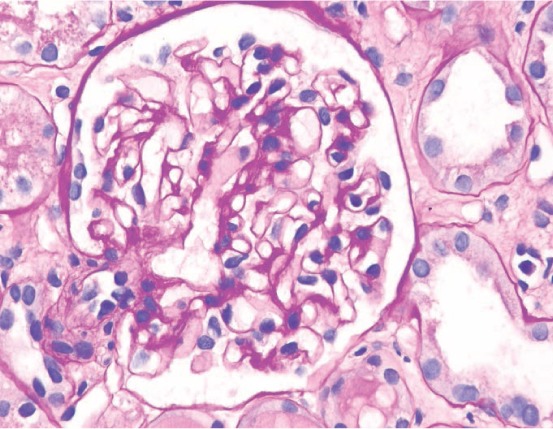

Laboratory tests showed a normal electrolyte panel with a blood urea nitrogen of 2 mg/dL and creatinine of 0.7 mg/dL. Liver function tests were within normal limits. Serum albumin and protein were significantly depressed at 1.1 and 4.1 g/dL, respectively. Computed tomography of the abdomen was only remarkable for diverticulosis. Urinalysis showed 3+ protein, < 1 red blood cells, and no casts, and 24-hour urine protein was significantly elevated at 6426 mg/vol. Total cholesterol was elevated at 246 mg/dL, with an elevated triglyceride of 254 mg/dL. Hemoglobin A1c was 6.7%. Autoimmune workup was negative and systemic lupus erythematosus was excluded. Complement C3 was 126 mg/dL (normal 85–200 mg/dL) and complement C4 was 24 mg/dL (normal 17–46 mg/dL). Viral panel including acute hepatitis panel, HIV, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus was also negative. Immunoglobulin panel was checked and showed an immunoglobulin A level of 172 mg/dL (normal 85–350), immunoglobulin M (IgM) level of 99 mg/dL (normal 60–300), and immunoglobulin G level of 193 mg/dL (normal 696–1488). Doppler analysis of the renal vasculature was unremarkable. For work-up of her abdominal pain, esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed a normal esophagus and gastritis with prominent gastric folds. Gastric mucosa showed no evidence of inflammation or dysplasia but was remarkable for edema and congestion. Colonoscopy revealed diverticulosis without diagnostic mucosal alteration. Ultimately, biopsy of the left kidney was performed. Renal pathology was remarkable for mesangial proliferation and mild segmental sclerosis on light microscopy (Figure 1), diffuse IgM deposits in the mesangial area on immunofluorescence with areas of focal C1q, and diffuse C4d deposits in the mesangium (Figure 2). No light chain deposits were identified. Electron microscopy was remarkable for effacement of visceral epithelial cells (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Glomerulus with mild segmental mesangial sclerosis (PAS stain, x 400).

Figure 2.

Glomerulus with mesangial deposition of immunoglobulin M (immunofluorescent staining, x 400).

Figure 3.

Electron microscopic study showing normal glomerular basement membrane, mild mesangial sclerosis, and segmental effacement of foot processes (electron microscopy, x 8000).

The patient was initially started on intravenous LASIX® and albumin infusions, which markedly improved her edema and resolved her gastrointestinal symptoms. Her serum albumin improved to 3.5 g/dL. She was started on a low-dose ACE inhibitor and maintained normal blood pressure readings. Treatment with prednisone (1 mg/kg) was initiated, and the patient was discharged home with instructions to follow up closely with her nephrologist. Two weeks after her initial presentation, she was readmitted to the hospital with dizziness and loss of consciousness. Brain magnetic resonance imaging without contrast showed an acute 1- to 2-mm infarction in the left cerebellar hemisphere without evidence of chronic ischemic disease. Her vital signs remained within normal range. Laboratory profile showed a creatinine level of 1.1 mg/dL and albumin of 3.5 g/dL. She was started on maximal medical management with antiplatelet agents and statin therapy and was discharged home without any neurologic deficits. Steroid treatment was resumed for IgM nephropathy, and she was advised to follow up with her nephrologist.

Discussion

Nephrotic syndrome is characterized by proteinuria in excess of 3.5 g/day, hypoalbuminemia, edema, and hyperlipidemia. Its primary causes include immunoglobulin A nephropathy, membranous glomerulopathy, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.4 IgM nephropathy is a rare cause of nephrotic syndrome and is a poorly understood glomerulopathy often seen in children and young adults.5,6

Our patient's kidney biopsy was consistent with diffuse IgM deposition, mild mesangial sclerosis, and effacement of foot processes. Currently, there is no consensus on the diagnosis of IgM nephropathy.1 It is defined by its immunohistologic features,7 and an underlying characteristic of this disease entity is diffuse IgM deposits on immunofluorescence. Complement deposits of C3 and C1q are often found along with the IgM deposits. Glomerular findings include minimal change disease and diffuse mesangial proliferation. Focal segmental glomerular sclerosis is not uncommon.7 Electron microscopy may show dense deposits in the mesangium and effacement of foot processes as seen in our patient.

The pathogenesis of the disease remains largely unknown. Although some studies have shown increased serum IgM or immune complex deposits, there has been no association with a structural abnormality of the IgM molecule.7 It appears that immune complex deposits such as C1q and C4d in the glomerular mesangium play a key role in the pathogenesis of the disease.7 It has been postulated that IgM-immune complex deposits in the mesangium result in a T-cell mediated inflammatory response leading to mesangial proliferation and glomeruli injury.8 IgM deposits may be seen in systemic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Alport syndrome, and rheumatoid arthritis.8,9 In our patient, we excluded systemic diseases including hypertension, infection, hypothyroidism, and connective tissue diseases.

Patients with IgM nephropathy can present with hematuria. However, most patients are asymptomatic. Hypertension is not typically seen on initial presentation but is often associated with longstanding disease. Progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is not common. In a case series reported by Mokhtar et al., only one of 23 patients with follow-up progressed to ESRD.5 In addition, Little et al. found that 7.4% of patients in their retrospective case study developed ESRD, and two of the four patients had focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.8 Hypertension and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis are factors associated with progression to ESRD.7–9 Women with hematuria have a favorable prognosis, and age appears to have no role as a prognostic indicator in this disease.3 Our patient presented primarily with nonspecific complaints of epigastric discomfort and generalized malaise. Her abdominal imaging including direct endoscopic evaluation all confirmed gastrointestinal congestion. In the absence of other etiology for her epigastric pain, we surmise that her nausea and epigastric discomfort were likely secondary to gut edema from nephrotic syndrome.

Thromboembolic events are a well-known complication of nephrotic syndrome. Although our patient had risk factors that predisposed her to thrombo-occlusive events, including her age and a history of diabetes and hypertension, she presented with an acute cerebellar thrombosis approximately 2 weeks after being diagnosed with IgM nephropathy. The absence of chronic ischemic disease on brain imaging further suggests that the acute cerebellar thrombosis was likely secondary to a hypercoagulable state from nephrotic syndrome and less likely from a vasculopathic state. When compared with the general population, patients with nephrotic syndrome have about an 8-fold increased risk of developing venous and arterial thromboembolic events.10 This case highlights the increased morbidity associated with a hypercoagulable state in nephrotic syndrome. The mechanism by which nephrotic syndrome causes a hypercoagulable state is unclear but is posited to be secondary to loss of proteins, including anticoagulants such as antithrombin III, plasminogen, protein C, and protein S.11 The incidence of thromboembolism in nephrotic syndrome is not well defined but is estimated to be between 2% and 42% for venous thrombosis and between 2% and 8% for arterial thromboembolism.12 The incidence of thromboembolism appears to be highest in the first 6 months following the diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome.10 Patients with severe hypoalbuminemia (< 2 g/dL) and those with membranous nephropathy have the greatest risk of thromboembolic complications.12 Although controversial, some experts recommend primary prophylaxis with anticoagulants in patients with nephrotic syndrome, particularly for those with severe hypoalbuminemia.12 Patients with IgA nephropathy appear to have the lowest risk of thromboembolic complications.13

There is no standardized treatment for IgM nephropathy. Steroids are the first line of treatment, and immunomodulatory drugs are the mainstay of therapy. About one-third of patients will be steroid-responsive while up to 50% of patients will become steroid resistant5,7 or steroid dependent.3

Conclusion

IgM nephropathy is a rare cause of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. It is immunohistologically characterized by deposition of IgM deposits in the glomerulus. Our patient presented with abdominal discomfort and was found to have significant hypoalbuminemia, proteinuria, and IgM deposition in the mesangium consistent with IgM nephropathy. Two weeks after her diagnosis, she presented with an acute cerebellar stroke. Although nephrotic syndrome is known to increase the risk of arterial and venous thromboembolism, it has not been hitherto reported with IgM nephropathy.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully thank Dr. Wadi Suki, in the division of nephrology, for his assistance with this manuscript, and Dr. Luan Truong, in the department of pathology, for providing the renal biopsy slides.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have completed and submitted the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal Conflict of Interest Statement and none were reported.

References

- 1.Mubarak M. IgM nephropathy; time to act. J Nephropathol. 2014 Jan;3(1):22–5. doi: 10.12860/jnp.2014.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van de Putte LB, de la Riviere GB, van Breda Vriesman PJ. Recurrent or persistent hematuria. Sign of mesangial immune-complex deposition. N Engl J Med. 1974 May 23;290(21):1165–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197405232902104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanikar A. IgM nephropathy; can we still ignore it? J Nephropathol. 2013 Apr;2(2):98–103. doi: 10.12860/JNP.2013.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Seigneux S, Martin PY. Management of patients with nephrotic syndrome. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009 Jul 25;139(29–30):416–22. doi: 10.4414/smw.2009.12477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mokhtar GA. IgM nephropathy: clinical picture and pathological findings in 36 patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2011 Sep;22(5):969–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawler W, Williams G, Tarpey P, Mallick NP. IgM associated primary diffuse mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis. J Clin Pathol. 1980 Nov;33(11):1029–38. doi: 10.1136/jcp.33.11.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mubarak M, Kazi JI. IgM nephropathy revisited. Nephrourol Mon. 2012 Fall;4(4):603–8. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little MA, Dorman A, Gill D, Walshe JJ. Mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis with IgM deposition: clinical characteristics and outcome. Ren Fail. 2000;22(4):445–57. doi: 10.1081/jdi-100100886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salmon AH, Kamel D, Mathieson PW. Recurrence of IgM nephropathy in a renal allograft. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004 Oct;19(10):2650–2. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahmoodi BK, ten Kate MK, Waanders F et al. High absolute risks and predictors of venous and arterial thromboembolic events in patients with nephrotic syndrome: results from a large retrospective cohort study. Circulation. 2008 Jan 15;117(2):224–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nandish SS, Khardori R, Elamin EM. Transient ischemic attack and nephrotic syndrome: Case report and review of literature. Am J Med Sci. 2006 Jul;332(1):32–5. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pincus KJ, Hynicka LM. Prophylaxis of thromboembolic events in patients with nephrotic syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2013 May;47(5):725–34. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2012 Jan;81(2):190–5. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]