Abstract

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a neurovascular disease that is strongly associated with an increase in the number and size of spontaneous microbleeds. Conventional methods of magnetic resonance imaging for detection of microbleeds, and positron emission tomography with Pittsburgh Compound B imaging for amyloid deposits, can separately demonstrate the presence of microbleeds and CAA in affected brains in vivo; however, there still is a critical need for strong evidence that shows involvement of CAA in microbleed formation. Here, we show in a Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease, that the combination of histochemical staining and an optical clearing method called optical histology, enables simultaneous, co-registered three-dimensional visualization of cerebral microvasculature, microbleeds, and amyloid deposits. Our data suggest that microbleeds are localized within the brain regions affected by vascular amyloid deposits. All observed microhemorrhages (n = 39) were in close proximity (0 to 144 µm) with vessels affected by CAA. Our data suggest that the predominant type of CAA-related microbleed is associated with leaky or ruptured hemorrhagic microvasculature. The proposed methodological and instrumental approach will allow future study of the relationship between CAA and microbleeds during disease development and in response to treatment strategies.

Keywords: Intracerebral hemorrhage, DiI, Thioflavin S, Prussian blue, Amyloid-β, Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, Microhemorrhages, Stroke

Introduction

Intracerebral microbleeds result from rupture or leaking of cerebral blood vessels. They are routinely visualized with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and are defined in humans as round foci <5 mm in diameter that appear hypointense and distinct from vascular flow voids, leptomeningeal hemasiderosis, and nonhemorrhagic subcortical mineralization (Fazekas et al., 1999). Hemosiderin, a hemoglobin breakdown product, causes magnetic susceptibility-induced relaxation, leading to T2* signal loss. Initially, microbleeds tend to be clinically asymptomatic. In the long term, they are a contributing factor to age-related mental decline and dementia (Gregoire et al., 2012; Poels et al., 2012; Poels et al., 2010).

Two categories of vascular events can lead to the formation of a microbleed. First, microscopic deposits of lysed red blood cell products found in postmortem human studies suggest that microvessels also may leak blood into the brain parenchyma, especially in vessels affected by cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) (Hartz et al., 2012). Second, occlusions of small vessels can prevent blood flow from reaching a region of the brain, leading to ischemic damage, followed by hemorrhagic conversion of the infarction site (Fisher, 1986). Study of the pathophysiology of these small lesions is limited due to the small size of the vessels involved, resulting in problems with early detection of microbleeds with contemporary MRI techniques.

CAA is a neurovascular disease that is strongly associated with the increase in the number and size of spontaneous microbleeds. CAA is characterized by the deposition of fibrillar forms of amyloid peptides in the blood vessels of the cortex and leptomeninges. Amyloid deposits on the cerebral vasculature promote degeneration of the tunica media and loss of smooth muscle and endothelial cells, inducing thickening of the vessel wall and vascular dysfunction (Vinters, 1987). Recently, we reported the progressive accumulation of CAA in parallel with microbleeds in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of amyloidosis (Fisher et al., 2011). Older Tg2576 mice develop CAA in leptomeningeal and pial vessels, which is associated with spontaneous microbleeds that can be further exacerbated by anti-amyloid immunotherapy (Fisher et al., 2011; Wilcock et al., 2004).

Combined in-vivo and ex-vivo analyses strongly imply co-localization of CAA affected regions and microbleeds (Ni et al., 2015). Several imaging methods exist to visualize both amyloid deposits and microhemorrhages, including 1) in-vivo MRI imaging for microbleeds (Chan and Desmond, 1999; Kwa et al., 1998), 2) in-vivo 11C-PIB Positron Emission Tomography (PET) for cerebral amyloid burden (Yates et al., 2011), 3) postmortem H&E and hemosiderin staining for microbleeds (Craelius et al., 1982; Fisher et al., 2011) and 4) postmortem Congo Red, Thioflavin S or immunostaining with anti-amyloid beta antibodies for amyloid deposits (Vinters et al., 1988). Microscopic analyses traditionally include two-dimensional histochemistry with Prussian blue for hemosiderin and Congo Red or Thioflavin S for amyloid deposits (Fisher et al., 2011; Wilcock et al., 2004). Multiphoton in-vivo microscopy enables co-registered visualization of amyloid deposits, blood vessels and cerebral cellular elements (Dong et al., 2010); however, there is a restriction in the analyzed size and volume. The entire brain vasculature can be visualized ex vivo and in three dimensions using the corrosion cast method (Meyer et al., 2008), although this method limits application of other immunohistochemical approaches to visualize other cerebral structures. However, none of the current methods combines microscopic resolution and three-dimensional structural analysis of the affected areas.

Here, for the first time, we show that the combination of histochemical staining and a new optical clearing method we call optical histology (Moy et al., 2013a, 2013b), enables simultaneous, co-registered three dimensional visualization of cerebral microvasculature, microbleeds, and amyloid deposits. With this combined approach, we present data that supports the hypothesis that microbleeds occur in the brain areas most affected by CAA in the Tg2576 model of amyloidosis.

Materials and methods

Animal model

We used naive 21–22-month-old Tg2576 mice (n = 4) and nontransgenic (nTg) (n = 2) littermates (Fisher et al., 2012; Hsiao et al., 1996). All animal procedures followed the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” from NIH publication No. 85-23 and were approved in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of California, Irvine.

Vessel painting

To achieve high-resolution, three-dimensional imaging of microscopic features in the brain, we used a technique called optical histology, described extensively in previous publications (Moy et al., 2013a, 2013b). The first step of optical histology involves fluorescent labeling of the microvasculature. Briefly, to label blood vessels, animals received a cardiac perfusion of DiI (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), a carbocyanine fluorescent dye, at a rate of 5 mL/min (Li et al., 2008; Moy et al., 2013b) followed by perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. After perfusion, brains were extracted and immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 72 h.

Tissue sectioning

Each brain was embedded in 5% agarose gel and placed into a 16 × 38 mm hollow cylinder. Using a micrometer (ThorLabs, New Jersey, USA) for precise positioning and a microtome blade (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), 500 µm-thick brain sections were generated. After sectioning, excess agarose was removed from each section.

Tissue staining and clearing

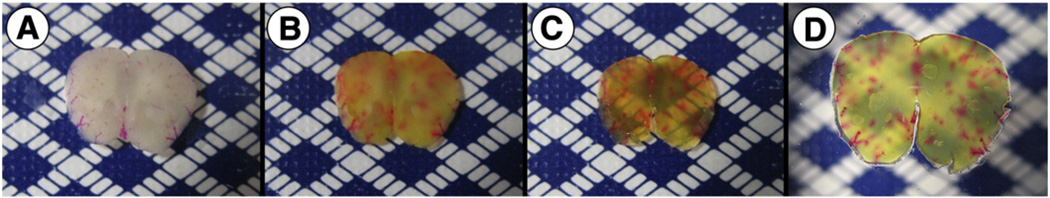

Each section was stained for hemosiderin and fibrillar beta-amyloid deposits using Prussian blue and Thioflavin S staining, respectively (Liu et al., 2014; Passos et al., 2013). Briefly, Prussian blue by Mallory modifications for hemosiderin was performed using freshly prepared 5% potassium hexacyanoferratetrihydrate and 5% hydrochloric acid (both Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in water for 60 min, followed by 3 washes in water, then brain sections were preincubated with 50% ethanol, followed by one-hour immersion in 0.5% Thioflavin S with mild agitation, two washes with 50% ethanol, two washes in PBS, and storage in PBS buffer. To render the samples transparent, brain sections were incubated in 0.3 mL of FocusClear (CelExplorer Labs, Hsinchu, Taiwan) for three hours. Cleared sections were placed in a custom-built tissue holder (Moy et al., 2013b). After tissue staining and clearing, a visual change in the appearance of the sections was observed from the combination of Prussian blue and Thioflavin S staining with the clearing of the tissue (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Brain sections preparation stages for optical histology. (A) 500 µm-thick wild-type mouse brain section stained with DiI before optical clearing. (B) Section after Prussian blue and Thioflavin S staining. (C) Section after optical clearing in FocusClear for three hours. (D) Brain section mounted between two glass cover slides.

Microscopy

A confocal microscope (Meta 150, Carl Zeiss, Germany) was used to visualize DiI-stained microvasculature and Thioflavin S-stained amyloid deposits. The fluorescence of DiI was collected using a 543 nm HeNe laser for excitation and a 565–615 nm bandpass filter for fluorescence emission. Thioflavin S fluorescence was collected using a 458 nm Argon laser for excitation and a 500–530 nm bandpass filter for emission. Since hemosiderin stained with Prussian blue is not fluorescent, transmission microscopy at 543 nm was used to visualize the absorption contrast of regions stained by Prussian blue. Z-stacks of the brain were collected using a 10× objective (Plan-Neofluar 10×/0.30 Ph1), allowing for 0.7 µm lateral resolution and 9 µm longitudinal resolution. A 20× objective (Plan-Neufluar 20×/0.5 Ph2) was employed to examine individual microbleed sites. In addition, brightfield microscopic images of the transilluminated brain section were collected with an inverted microscope (Diaphot TMD, Nikon, Melville, NY) equipped with a color CCD camera (Grasshopper, Point Grey, Richmond, BC, Canada).

Image processing

Algorithms in ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/index.html) and Fiji, an open-source plugin (Preibisch et al., 2009), were used to create a wide-field mosaic image comprised of adjacent microscope fields of view, and to generate fly-through videos and maximum intensity projection (MIP) images of fluorescence emission and absorption contrast. The ImageJ “Analyze Particles” function with a threshold diameter of 5 µm was used to determine the area and number of amyloid deposits in the MIP image of each brain section. Hemosiderin size was assessed using the ImageJ “Scale Bar” feature.

Results and discussion

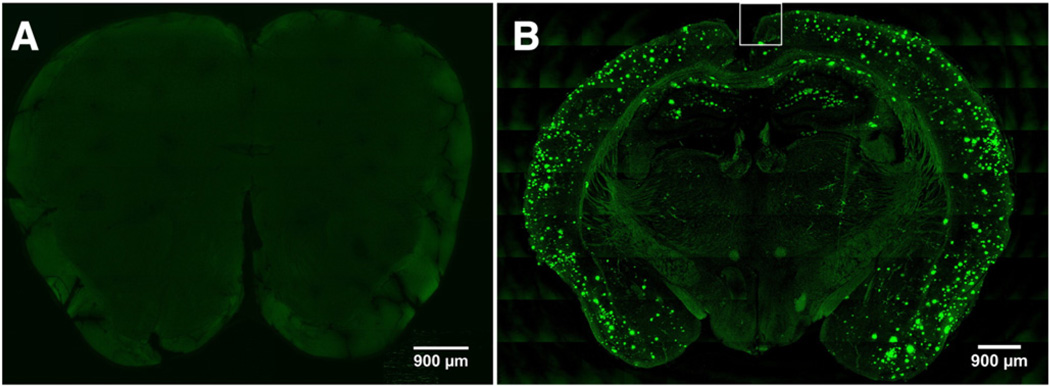

Thioflavin S staining revealed amyloid deposition only in Tg2576 mouse brain sections (Fig. 2B) but not in wild-type brain sections (Fig. 2A)

Fig. 2.

Representative MIP images of a (A) wild-type and (B) Tg2576 mouse brain section. (A) Thioflavin S positive amyloid deposits are absent in the wild-type mouse brain section. (B) In Tg2576 mouse brain sections, amyloid deposits are evident as punctate green areas associated with Thioflavin S fluorescence and are located primarily in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus regions. The region enclosed by the white line in (B) is further discussed in Fig. 3.

In comparison with wild-type brain sections (Fig. 2A) that did not exhibit distinct fluorescent features associated with Thioflavin S, the Tg2576 brain sections demonstrate well-defined fluorescent regions representing fibrillar amyloid deposits stained with Thioflavin S (Fig. 2B). These regions were specifically localized in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 2B) areas of the brain. In one section, 1528 amyloid deposits with a mean diameter of 33 µm were identified (range: 6–175 µm).

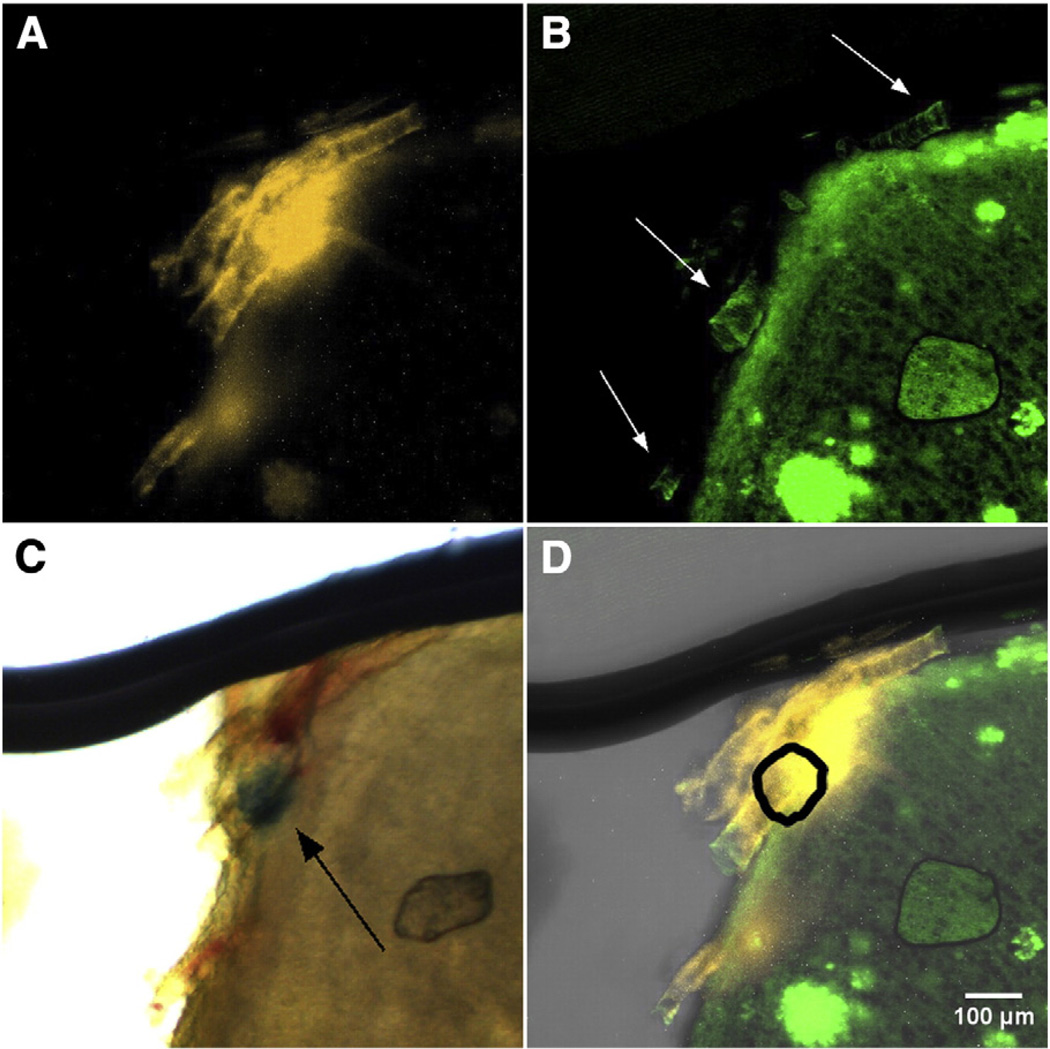

Microbleeds are localized in CAA-affected brain regions

Within regions of interest, we identified labeled structures that suggest a link between cerebral microbleeds and vascular-associated fibrillar amyloid, a hallmark of CAA pathology (Fig. 3, Supplemental Fig. 1). As a representative example, in the subregion of interest identified in Fig. 2B, we observed DiI-labeled vasculature (Fig. 3A, Supplemental Figs. 1A, 3A) and vascular amyloid (Fig. 3B, white arrows, Supplemental Figs. 1B, 3B). With transmission (Supplemental Fig. 1C) and brightfield microscopy (Fig. 3C, Supplemental Fig. 1D), we observed non-fluorescent Prussian blue positive hemosiderin (Fig. 3C, black arrow) that was adjacent to vascular amyloid (Fig. 3D). With overlays of the co-registered microscopy images, the spatial overlap of vascular amyloid, hemosiderin, and Prussian blue is more readily visualized (Fig. 3D, Supplemental Fig. 1E).

Fig. 3.

(A, B) Representative MIP images of (A) DiI-stained microvasculature and (B) Thioflavin S-stained amyloid deposits from the cerebral cortex of a Tg2576 mouse brain (10× magnification). In (B), regions of vascular amyloid fluorescence (indicated with white arrows) are evidence of CAA pathology. (C) Brightfield microscopy enables visualization of Prussian blue-stained hemosiderin (black arrow). (D) Merged MIP images from (A), (B), and absorption contrast demonstrate co-localization of the vascular amyloid and microbleed. The shape and position of non-fluorescent hemosiderin identified in (C), is shown with the thick black line. A fly-through video (Supplementary Video 1) is provided in the Supplemental materials' section. The thick line at the top of the images is a shadow from the tissue holder used to support the cleared brain section.

Three-dimensional visualization with optical histology enables identification of leaky vessels closely associated with CAA pathology (Fig. 4, Supplemental Figs. 2 and 3)

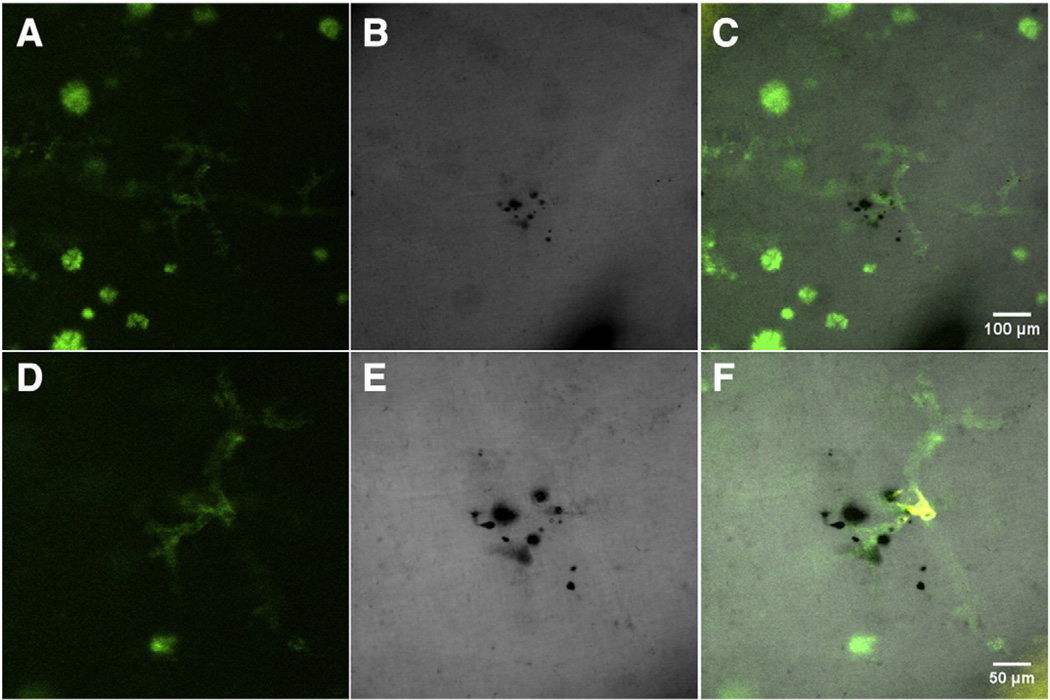

Fig. 4.

Hippocampus region of Tg2576 mouse brain section stained with Thioflavin S (A, D) and Prussian blue (B, E), imaged with the 10× (A, B, C) and 20× (D, E, F) objectives. (A, D) Vascular amyloid and amyloid plaques stained with Thioflavin S are visualized with green fluorescence emission. (B, E) The absorption contrast of hemosiderin stained with Prussian blue is indicative of a microbleed and characterizes a leaky/ruptured hemorrhagic vessel. (C, F) Following merging of images from Fig. 2 (A, B, D, E) with those of DiI fluorescence, we identified that the microbleed was associated with CAA-affected vasculature. A fly-through video (Supplementary Video 2) of Figs. (D–F) is provided in the Supplemental materials' section.

After merging the images of DiI, Thioflavin S, and transmission microscopy channels, clusters of hemosiderin along the vessel were detected. The hemosiderin is observed by absorption contrast and appears as black (Fig. 4A, Supplemental Figs. 2B, 3C) and confirmed with brightfield microscopy (Supplemental Figs. 2C, 3D). Combining Prussian blue staining of hemosiderin with tracing of the CAA-affected cerebral vessel, we identified the presence of a leaky/ruptured vessel in the Tg2576 mouse brain section (Fig. 4B, Supplemental Figs. 2D, 3E).

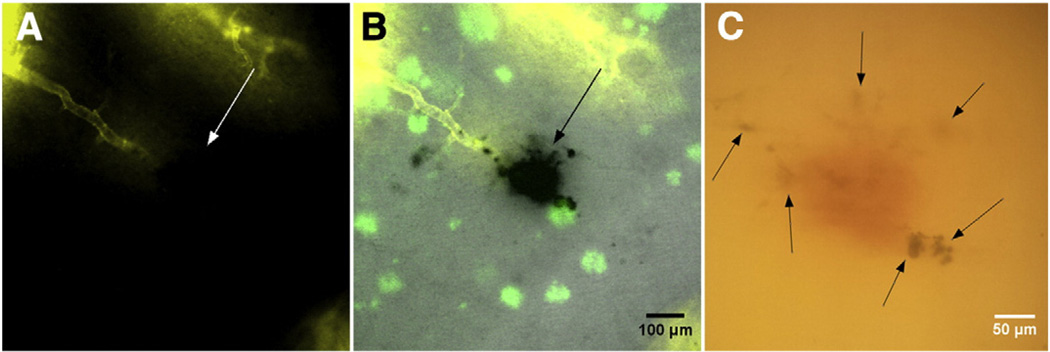

Optical histology enabled identification of a single occurrence of an apparently occluded vessel in Tg2576 mice with the CAA pathology (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5.

Hippocampus region of Tg2576 mouse brain section with an occluded ischemic vessel and hemosiderin deposition (A) DiI vessel painting reveals vascular structure that terminates abruptly (white arrow), suggesting either a blood clot or narrowing of the vessel. (B) With merged fluorescence and transmission microscopy channels, a cerebral microbleed is clearly evident (black arrow). Scale bar = 100 µm. (C) The microbleed is confirmed with brightfield microscopy, which shows both extravasated red blood cells (diffuse red region in center) and Prussian blue-stained hemosiderin (black arrows), suggesting transformation of ischemia into a hemorrhagic event. Scale bar = 50 µm. A fly-through video (Supplementary Video 3) of this section is provided in the Supplemental materials' section.

DiI staining enabled identification of a microvessel that appeared to be occluded (Fig. 5A, white arrow). Merging the images from three channels in a manner similar to Fig. 4F, we identified a microischemic lesion that apparently transformed into a ~130 µm-wide hemorrhagic microbleed (Fig. 5B,C). Co-localization of red blood cells and hemosiderin inside the brain parenchyma further supports the transformation of ischemia into a hemorrhagic event. Such ischemic events were not present in brain sections of wild-type animals.

Collectively, our data from nine Tg2576 mouse brain sections suggest that cerebral microbleeds are heterogeneous in terms of size and location

From these sections, we identified 39 microbleeds with characteristic diameters ranging from 5 to 240 µm (median diameter = 39 µm). Of the 39 microbleeds, 30 occurred within the cerebral cortex and nine within the hippocampus; all were closely localized with the distribution of fibrillar forms of amyloid deposits, with a median distance of 0 µm between the vessel and amyloid (range: 0–144 µm). Twelve (31%) microbleeds originated from capillaries (≤10 µm diameter) and 27 (69%) from venules and arterioles (10 to 70 µm). These preclinical findings are consistent with clinical MRI data (Poels et al., 2010) showing a median diameter of the CAA-affected vessels of 17 µm (range: 3–50 µm), suggesting that microbleeds arise primarily from small arterioles. Of the 39 microbleeds, all but one (Fig. 5) demonstrated characteristics of leaky/ruptured hemorrhagic blood vessels (Fig. 4). Additional studies are warranted to assess the potential relationship between CAA and microbleed formation; optical histology is expected to facilitate these studies.

In the transgenic mouse data sets, the CAA fluorescence is strong overall interrogated depths, suggesting that the optical clearing process was effective. In the wild-type mice, the DiI fluorescent signal also was strong; however, in the transgenic mice, the DiI fluorescent signal was less consistent. This may be due to compromised vascular staining due to vascular amyloid deposition and compromised flow in smaller vessels in Tg animals (Meyer et al., 2008). Additional work is planned to study this discrepancy and ascertain the reasons underlying this difference.

Optical histology enables high-resolution and wide field-of-view imaging of bulk tissue sections across multiple body planes. With the combination of thick-tissue sectioning, chemical-based optical clearing, and fluorescence microscopy, we can study tissue depths that would otherwise be inaccessible. Future studies that stem from optical histology can include visualizing multiple fluorescently-labeled structures (Moy et al., 2013a) in brain sections that allow comprehensive characterization of cerebral pathology. Optical histology can also expand into pharmacological studies by evaluating treatment efficacy and response through visualization of biological markers at a high resolution and wide field-of-view.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kelley Kilday, Sneha Shivkumar and Dr. Tatiana Krasieva (University of California, Irvine) for their intellectual contributions to this project. The work was supported in part by the Alzheimer's Association (NIRG-12-242781), Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation, the National Institutes of Health Laser Microbeam and Medical Program (LAMMP, a P41 Technology Research Resource, grant number EB015890), and the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program at University of California, Irvine.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mvr.2016.02.002.

Contributor Information

Patrick Lo, Email: pclo@uci.edu.

Christian Crouzet, Email: ccrouzet@uci.edu.

Vitaly Vasilevko, Email: vvasilev@uci.edu.

Bernard Choi, Email: choib@uci.edu.

References

- Chan S, Desmond DW. Silent intracerebral microhemorrhages in stroke patients. Ann. Neurol. 1999;45:412–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craelius W, et al. Iron deposits surrounding multiple sclerosis plaques. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1982;106:397–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, et al. Multiphoton in vivo imaging of amyloid in animal models of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeka F, et al. Histopathologic analysis of foci of signal loss on gradient-echo T2*-weighted MR images in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: evidence of microangiopathy-related microbleeds. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1999;20:637–642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M. Aspirin, anticoagulants, and hemorrhagic conversion of ischemic infarction: hypothesis and implications. Bull. Clin. Neurosci. 1986;51:68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, et al. Therapeutic modulation of cerebral microhemorrhage in a mouse model of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 2011;42:3300–3303. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, et al. Mixed cerebrovascular disease and the future of stroke prevention. Transl. Stroke Res. 2012;3:39–51. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0185-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire SM, et al. Cerebral microbleeds and long-term cognitive outcome: longitudinal cohort study of stroke clinic patients. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2012;33:430–435. doi: 10.1159/000336237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz AM, et al. Amyloid-beta contributes to blood–brain barrier leakage in transgenic human amyloid precursor protein mice and in humans with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 2012;43:514–523. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.627562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, et al. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwa VI, et al. Silent intracerebral microhemorrhages in patients with ischemic stroke. Amsterdam Vascular Medicine Group. Ann. Neurol. 1998;44:372–377. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, et al. Direct labeling and visualization of blood vessels with lipophilic carbocyanine dye DiI. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1703–1708. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, et al. Comparative analysis of H&E and Prussian blue staining in a mouse model of cerebral microbleeds. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2014 doi: 10.1369/0022155414546692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EP, et al. Altered morphology and 3D architecture of brain vasculature in a mouse model for Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:3587–3592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709788105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy AJ. High-resolution visualization of mouse cardiac microvasculature using optical histology. Biomed Opt. Express. 2013a;5:69–77. doi: 10.1364/BOE.5.000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy AJ. Optical histology: a method to visualize microvasculature in thick tissue sections of mouse brain. PLoS ONE. 2013b;8:e53753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni J, et al. Cortical localization of microbleeds in cerebral amyloid angiopathy: an ultra high-field 7T MRI study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43:1325–1330. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos GF, et al. The bradykinin B1 receptor regulates Abeta deposition and neuroinflammation in Tg-SwDI mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2013;182:1740–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poels MM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of cerebral microbleeds: an update of the Rotterdam scan study. Stroke. 2010;41:S103–S106. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poels MM, et al. Cerebral microbleeds are associated with worse cognitive function: the Rotterdam scan study. Neurology. 2012;78:326–333. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182452928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preibisch S, et al. Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3Dmicroscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1463–1465. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinters HV. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy. A critical review. Stroke. 1987;18:311–324. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinters HV, et al. Immunohistochemical study of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. II. Enhancement of immunostaining using formic acid pretreatment of tissue sections. Am. J. Pathol. 1988;133:150–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcock DM, et al. Passive immunotherapy against Abeta in aged APP-transgenic mice reverses cognitive deficits and depletes parenchymal amyloid deposits in spite of increased vascular amyloid and microhemorrhage. J. Neuroinflammation. 2004;1:24. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates PA, et al. Cerebral microhemorrhage and brain beta-amyloid in aging and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77:48–54. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318221ad36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.