Summary

The Standardized Trauma and Resuscitation Team Training (S.T.A.R.T.T.) course focuses on training multidisciplinary trauma teams: surgeons/physicians, registered nurses (RNs), respiratory therapists (RTs) and, most recently, prehospital personnel. The S.T.A.R.T.T. curriculum highlights crisis management (CRM) skills: communication, teamwork, leadership, situational awareness and resource utilization. This commentary outlines the modifications made to the course curriculum in order to satisfy the learning needs of a bilingual audience. The results suggest that bilingual multidisciplinary CRM courses are feasible, are associated with high participant satisfaction and have no clear detriments.

The Standardized Trauma and Resuscitation Team Training (S.T.A.R.T.T.) course1,2 focuses on training multidisciplinary trauma teams: surgeons/physicians, registered nurses (RNs), respiratory therapists (RTs) and, most recently, prehospital personnel.3 The S.T.A.R.T.T. curriculum highlights crisis management (CRM) skills: communication, teamwork, leadership, situational awareness and resource utilization.1–3 S.T.A.R.T.T. was designed to meet the needs of each participant discipline while bolstering common skills required by all team members.1,2

Previously, the course has been delivered only in English; however, the opportunity of a national conference in Quebec spurred its next evolution: to teach simultaneously in English and French and to address language barriers. To our knowledge there are no other published reports concerning the challenges and successes associated with bilingual simulation courses.

S.T.A.R.T.T. is typically held alongside national meetings of the Canadian Surgery Forum (CSF) and the Trauma Association of Canada (TAC). Unlike multidisciplinary TAC meetings, the CSF is typically for surgeons only. Therefore the physicians participating in the S.T.A.R.T.T course at this meeting generally come from across Canada and speak only English. On the other hand, the RNs and RTs who participate are generally recruited locally. For this particular course in French-speaking Quebec, the RNs and RTs were again recruited locally, and all were primary French speakers professionally (though many could communicate to some degree in English). There was concern about teaching a course that promotes realistic teamwork and communication but not doing so in all attendees’ working language. This led to extensive efforts to ensure that S.T.A.R.T.T not only bridged the discipline gap, but also the language gap.

First, the conference was co-hosted by an English- and a French-speaker, who co-introduced each session. Introductory lectures on CRM and trauma teams were then accompanied by printed slides offered in both English and French.

Next, participants were divided into mixed-language trauma teams for introductory “icebreaker” simulations. These simulations were deliberately low-fidelity (to avoid cognitive overload) and nonmedical (to focus on relationship building and team communication). Specifically, this exercise consisted of teams building paper chains of varying design complexity and following instructions of varying complexity. Such exercises can illustrate key aspects of teamwork, including the need to communicate clearly, to cite names, to close the loop (i.e., all instructions are confirmed as received and confirmed when completed), to ensure a shared mental model (i.e., everyone is “on the same page”), to establish a leader and to decide whether tasks can be broken into parts. These exercises allow team members to bond, gain empathy and foster trust before applying medical knowledge or manual skills.

The course then progressed to more complex high-fidelity trauma simulations. Our usual format has senior instructors/expert debriefers spend the day as “team coaches” with their assigned teams. This avoids duplication of teaching points and gradually builds the teams’ sophistication in terms of communication and teamwork.2,3 We maintained this structure but provided 2 coaches (1 English and 1 bilingual) to each team.

Many CRM ideas originate with aviation.4 Pilots refer to “flying by voice” as much as “flying by instruments.” Similarly, trauma teams may “resuscitate by voice” as much as by drugs or equipment. Therefore, we added simulations of telephone calls to the S.T.A.R.T.T. course. These simulations further highlighted communication as an essential trauma skill separate from factual recall or manual dexterity. They also allowed participants working in their second languages to focus purely on communication. However, we discovered unique benefits of these telephone simulations. They were inexpensive and logistically simple; all that was needed were telephones in different rooms and an instructor assuming the role of a geographically distant doctor. This exercise also prompted a discussion about how telephone referrals differ across Canada, which further led to discussions about how they might be improved, the need for practitioners to understand their local systems and how urban health care workers can support those in relatively underserviced areas.

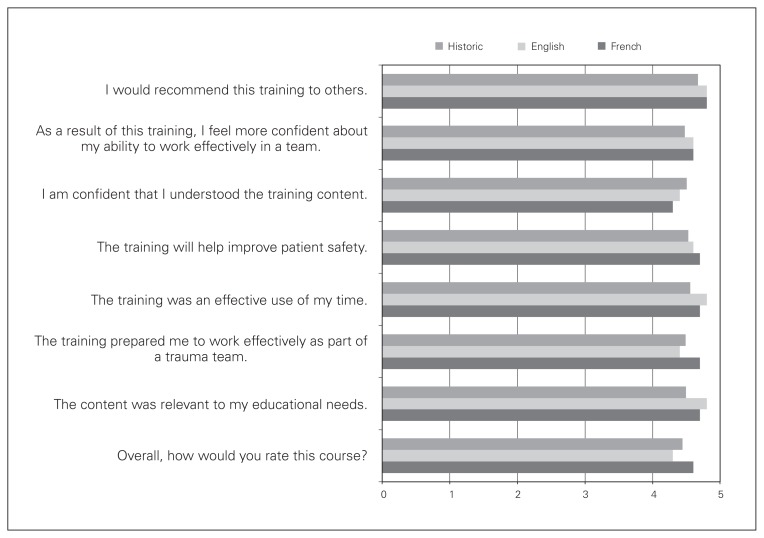

We expected course feedback to focus on the language issue. Interestingly, it did not; as with previous courses, comments focused on course content. This may explain why we received predominantly positive feedback and why it was largely identical to that from previous courses (Fig. 1).1–3 Because participants did not even comment on language, it may have been a nonissue for attendees, meaning faculty concerns were unfounded. Alternatively, the lack of feedback on language may mean that the extra efforts were worthwhile.

Fig. 1.

Participant responses to satisfaction survey by first language of participant, compared with historical data from previous courses.

Language gaps likely exist across specialties, even when all specialists speak the same root language. The term “Tower of Babel syndrome” has been coined5 to describe situations when, for example, the same patient is identified by nurses as “bed 4,” by surgeons as “the perforated bowel,” by intensivists as “the septic shock,” and by anesthesiologists as “the difficult airway.” By having health care professions separated by actual languages, we were able to illustrate the potential dangers inherent in our medical dialects.

The language gap appeared to reinforce the CRM teaching points by emphasizing that communication is more than just what you say. While verbal communication refers to the words spoken, paraverbal communication refers to how loud, emotional or rushed that communication is, and nonverbal communication refers to eye contact, hand gestures, body language and facial expressions. Communication courses typically focus solely on verbal communication even though other forms are just as important4 or more important if verbal and nonverbal communication are discordant (e.g., you say, “I don’t need help,” but your facial expressions suggest otherwise). Our language gap spurred a greater discussion of verbal, paraverbal and nonverbal communication.

Despite the limitations of participant course evaluations, there was no evidence that the language gap was a hindrance to the course. The bilingual format may have helped both attendees and faculty understand the importance of communication and team empathy. The format provided a “disruptive innovation” that helped the S.T.A.R.T.T. course to evolve further. Bilingual simulation also provided the stimulus to test novel ideas that can supplement the course, regardless of future location or language.

While the course was objectively and subjectively successful, it had limitations. Preparation time was longer, instructors were selected for language ability as well as content expertise, and, while perhaps not necessary, we pre-emptively reduced attendee numbers. Because instruction and debriefing occurred in both languages, extra time was spent translating, repeating and speaking more slowly. This presumably meant less content was covered overall, duplication for bilingual participants and periodic disengagement for unilingual participants.

Our results suggest that bilingual multidisciplinary CRM courses are feasible, are associated with high participant satisfaction and have no clear detriments. However, this high satisfaction was associated with extra preparation and additional human resources. The increased focus on communication did not obviously detract from other learning objectives. Instead, 2 languages may have been an unexpected plus.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors: All authors contributed substantially to the conception, writing and revision of this article and approved the final version for publication.

References

- 1.Ziesmann MT, Widder S, Park J, et al. S.T.A.R.T.T. — development of a national, multi-disciplinary trauma crisis resource management curriculum: results from the pilot course. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:753–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182a925df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillman LM, Brindley PG, Paton-Gay JD, et al. Standardized Trauma And Resuscitation Team Training (S.T.A.R.T.T.) course — evolution of a multidisciplinary trauma crisis resource management simulation course. Am J Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.07.024. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillman LM, Martin D, Engels PT, et al. S.T.A.R.T.T. plus: addition of pre-hospital personnel to a national multi-disciplinary crisis resource management trauma team training course. Can J Surg. 2016;59:9–11. doi: 10.1503/cjs.010915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.St Pierre M, Hofinger G, Buerschaper C. Crisis management in acute care settings: human factors and team psychology in a high stakes environment. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tower of Babel Syndrome. [accessed 2015 Sept. 1]. http://medicaldictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Tower+of+Babel+Syndrome.