Abstract

Background

The social stigma and chronicity of psoriasis significantly affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Objective

We examined the effect of three regimens of secukinumab on HRQoL in moderate to severe psoriasis patients.

Methods

12-week data from a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, regimen-finding study evaluated HRQoL, measured by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). Secukinumab or placebo was administered subcutaneously in three treatment regimens: single (baseline only), monthly (baseline, weeks 4, 8), early (baseline, weeks 1, 2, 4). Differences among regimens were assessed with logistic regression models and Fisher's exact test.

Results

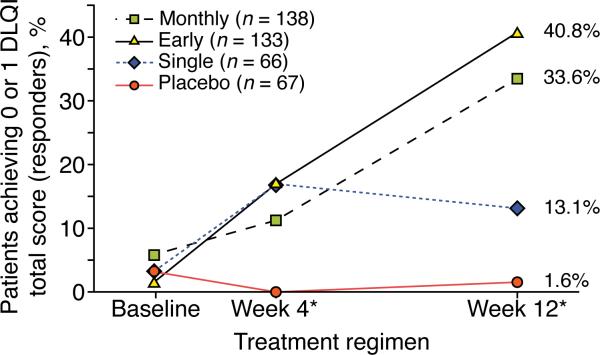

Patients (n = 404) were randomized to single (baseline) treatment regimen, n = 66; monthly, (baseline, weeks 4 and 8), n = 138; early, (baseline, weeks 1, 2, 4), n = 133; and placebo, n = 67. DLQI response was significantly higher in early, monthly, and single regimens than in placebo regimen (40.8 %, 33.6 %, and 13.1 % vs. 1.6 %, respectively; P < 0.001 for all).

Conclusion

Moderate to severe psoriasis patients receiving monthly and early treatment with secukinumab demonstrated improved HRQoL compared with placebo.

INTRODUCTION

Plaque psoriasis, a chronic, immune-mediated skin disease, affecting approximately 2 % of the world's population,1 is characterized by well-defined severely inflamed plaques, with scaling. It is commonly found on the scalp, elbows, knees, and trunk and may be associated with severe itch and pain. Its cause is unknown. Although psoriasis has a genetic component that may determine disease severity and age of onset, its manifestation may be triggered by environmental factors.2 Due to the social stigma and chronic nature of psoriasis, patients may experience life-long psychological burden and reduced mental and physical functioning.3–7 Psoriasis's impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is comparable to diabetes or cancer.8

The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI)9 or the Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) may be used to clinically evaluate psoriasis severity.10 However, these scores do not measure disease burden or HRQoL.11–13 Measuring HRQoL is important in assessing psoriasis and its treatment.14

Biologic agents have been shown to improve symptoms of moderate to severe psoriasis, especially in patients with poor response to conventional systemic therapy.15,16 Secukinumab (Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland), a fully human immunoglobulin 17A monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin 17, has shown efficacy and tolerability in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.17,18 In a previously-reported phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, regimen-finding trial18 of secukinumab, the primary objective was the achievement of PASI 75 response at week 12 in patients in single, early, and monthly treatment regimens. As reported by Rich et al.,18 early and monthly regimens resulted in significantly higher rates of PASI 75 response than the placebo regimen at week 12 (54.5 % [n = 72] and 42.0 % [n = 58], respectively, vs. 1.5 % [n = 1]; P < 0.001 for both); the single regimen did not (10.6 % [n = 7]; P = 0.225). PASI 90 response rates were significantly greater with the early and monthly regimens than with placebo (31.8 % [n = 42] and 17.4 % [n = 24], respectively, vs. 1.5 % [n = 1]; P < 0.001 for both) but not with the single regimen (3.0 % [n = 2]; P = 0.556).

Secondary trial objectives also included an analysis of HRQoL assessed at week 12 of treatment. This article reports the results of the effects of these 3 secukinumab regimens on HRQoL in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

METHODS

Patient Population

The population consisted of patients 18 years and older with chronic, moderate to severe, plaque-type psoriasis (defined as a PASI of ≥ 12, a body surface area of ≥ 10 %, and an IGA score of ≥ 3 [scale: 0-5]) inadequately controlled by topical treatment, phototherapy, and/or previous systemic therapy. Details of the patient population of the trial were previously described.18 Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to study initiation. The study complied with Good Clinical Practices and the Declaration of Helsinki and each study site received approval from an institutional review board or ethics committee. The study was registered on July 16, 2009, at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00941031).

Study Design

The study was conducted from July 28, 2009, to December 16, 2010, in 60 centers in the following countries: France (2), Germany (13), Iceland (1), Israel (3), Japan (10), Norway (3), and the United States of America (28).

At the baseline visit of the 12-week induction phase, eligible patients were stratified according to body weight (≥ 90 kg or < 90 kg) and randomized to single (active treatment at baseline only), monthly (baseline and weeks 4 and 8), early (baseline and weeks 1, 2, and 4), or placebo treatment regimen in a ratio of 1:2:2:1. All patients were administered subcutaneous injections of 150-mg secukinumab or placebo at all treatment time points (baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, and 8).18

After the initial treatment phase, patients were randomized to different maintenance treatments for the remaining 24 weeks of treatment (results are not reported here).

Patient-reported Outcomes

Patients completed the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) at baseline and weeks 4 and 12. This instrument has been validated for use in psoriasis19 and is used extensively in the assessment of psoriasis HRQoL.20

Dermatology Life Quality Index

The DLQI21 is a dermatology-specific, patient-completed, assessment tool of psoriasis HRQoL.22,23 The instrument contains 10 validated questions assessing six functional scales (symptoms and feeling, sleep, leisure/daily activities, school/holidays, personal relationships, and treatment).21 Each question is answered using the following scale:

■ 0: “not at all”

■ 1: “a little”

■ 2: “a lot”

■ 3: “very much”

The scores from all questions are summed to generate a total score (0-30) and are interpreted as follows:24

■ 0-1: no effect at all

■ 2-5: small effect

■ 6-10: moderate effect

■ 11-20: very large effect

■ 21-30: extremely large effect

Statistical Analysis

The DLQI scores were descriptively analyzed; medians with 25 % and 75 % percentiles were reported. Differences among the four treatment regimens were analyzed using the van Elteren test, stratified by body weight and questionnaire language.

Responders were identified as having a DLQI score of 0 or 1. Summary statistics were provided for the number of patients achieving a DLQI score of 0 or 1. The dichotomized DLQI score at week 12 was analyzed using Fisher's exact test for differences among the four regimens. In addition to descriptive analyses, these data were analyzed using a logistic regression model, adjusted for absolute baseline DLQI score as a continuous variable (range: 0-30) to show relative improvement among treatment regimens.

Treatment Regimen

The main purpose of this analysis was to test for differences among each of the four regimens. HRQoL scores were analyzed using regression modeling techniques. Treatment was included as a fixed effect, using the four unordered treatment regimens.

When outcome data were available after week 4 but not week 12, last observation was carried forward and imputation was used. When outcome data were not available at either the baseline or the follow-up visits, that patient was excluded from that analysis. All analyses were conducted on the full intention-to-treat population, using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Regression models were adjusted for body-weight stratum (≥ 90 kg or < 90 kg) and geographic region (Germany, Japan, United States, and other). All statistical tests were two-sided; an alpha level of 0.05 or less identified statistically significant treatment differences. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made.

Sensitivity Analyses

To investigate the robustness of the findings in the primary analysis, the DLQI analysis was repeated, adjusting for dichotomized baseline DLQI rather than the absolute baseline score.

RESULTS

Patient Population

A representative population of 404 male and female patients (Germany, n = 112; Japan, n = 43; the United States, n = 177; other countries, n = 72) with moderate to severe psoriasis were randomized (single, n = 66; monthly, n = 138; early, n = 133; placebo, n = 67) and received at least one dose of study medication. Of these, 380 (94.1 %) completed the 12-week initial treatment phase. At least 80 % of all randomized patients completed all HRQoL questionnaires. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were well balanced across treatment regimens at baseline (Table 1).

Table I.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics, Total and by Treatment Regimen

| variable | Single (n = 66) | Monthly (n = 138) | Early (n = 133) | Placebo (n = 67) | Total (n = 404) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (SD) | 42.7 (11.32) | 44.2 (12.96) | 44.5 (12.45) | 44.2 (12.59) | 44.1 (12.44) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 53 (80.3) | 104 (75.4) | 105 (78.9) | 44 (65.7) | 306 (75.7) |

| Weight, n (%) | |||||

| < 90 kg | 32 (48.5) | 68 (49.3) | 70 (52.6) | 35 (52.2) | 208 (51.5) |

| ≥ 90 kg | 34 (51.5) | 70 (50.7) | 63 (47.4) | 32 (47.8) | 196 (48.5) |

| Duration of psoriasis, years (SD) | 17.5 (10.05) | 16.9 (11.47) | 17.4 (11.82) | 15.4 (10.70) | 16.9 (11.23) |

| PASI score, mean (SD) | 19.9 (6.73) | 20.8 (8.08) | 19.9 (7.81) | 20.5 (9.31) | 20.3 (7.99) |

| Presence of psoriatic arthritis, n (%) | 15 (22.7) | 45 (32.6) | 39 (29.3) | 12 (17.9) | 111 (27.5) |

| BSA affected by plaque psoriasis, mean % (SD) | 21.8 (13.50) | 23.8 (16.84) | 22.8 (14.65) | 21.7 (15.99) | 22.8 (15.45) |

| DLQI total score, mean (SD) | 11.3 (6.88) | 11.8 (7.05) | 11.8 (6.72) | 12.5 (6.17) | 11.8 (6.76) |

BSA = body surface area; DLQI = Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI = Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; SD = standard deviation.

DLQI

A significant proportion of patients receiving monthly and early regimens achieved a DLQI total score of 0 or 1 after weeks 4 and 12 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Plaque Psoriasis. Percentages of Patients Achieving DLQI Total Score of 0 or 1 at Baseline and at Weeks 4 and 12, by Treatment Regimen

DLQI = Dermatology Life Quality Index.

* P < 0.001 for difference of active treatment regimen to placebo.

note: Patients with DLQI score of ≤ 1 were assessed as responders to treatment. Patients in the early and monthly regimens showed significant improvement in response when compared with patients in the placebo regimen.

A reduction in median DLQI total score was observed for all secukinumab regimens (Table 2); the largest changes were in the monthly and early regimens. Significant differences among all four regimens were found after both 4 and 12 weeks.

Table II.

DLQI Median Total Score at Baseline, Week 4, and Week 12, by Treatment Regimen

| Assessment period | Single (n = 66) | Monthly (n = 138) | Early (n = 133) | Placebo (n = 67) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, n (%) | 65 (98.5 %) | 136 (98.5 %) | 132 (99.3 %) | 67 (100.0 %) |

| median (25; 75 percentiles) | 10.0 (5.5; 15.0) | 11.0 (6.0; 17.5) | 11.0 (7.0;16.0) | 12.0 (8.0; 17.0) |

| Week 4, n (%) | 64 (97.0 %) | 133 (96.4 %) | 130 (97.7 %) | 65 (97.0 %) |

| median (25; 75 percentiles) | 6.0 (2.0; 11.0)* | 3.0 (3.0; 11.5)* | 5.0 (2.0; 9.0)* | 11.0 (6.0; 18.0) |

| Week 12, n (%) | 62 (93.9 %) | 132 (95.7 %) | 128 (96.2 %) | 58 (86.6 %) |

| median (25; 75 percentiles) | 7.5 (3.0; 11.0)** | 4.5 (1.0; 8.0)* | 3.0 (1.0; 18.0)* | 12.0 (6.0; 19.0) |

DLQI = Dermatology Life Quality Index.

P ≤ 0.001 compared with placebo

P = 0.003.

Logistic regression modeling of the week 12 dichotomized DLQI score in the sensitivity analysis produced unreliable estimates of treatment difference (single: odds ratio [OR], 8.31; 95 % confidence interval [CI], 1.41-158.88; monthly: OR, 33.75; 95 % CI, 6.78-613.95; early: OR, 46.31; 95 % CI, 9.34-841.87), when compared with placebo, due to the paucity of DLQI responders in the placebo regimen.

DISCUSSION

The secondary analyses of this phase 2 study showed that multiple-dose treatment regimens of secukinumab compared to placebo substantially improved HRQoL in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. The largest benefit was seen in early treatment regimen, although results should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size.

There is increasing agreement that patient-reported HRQoL should be assessed when evaluating new therapies for psoriasis.25 Similar findings have resulted from trials in similar patient populations treated with biologics. Shikiar et al.26 reported significant improvements in DLQI and EQ-5D scores after 12 weeks of Adalimumab treatment. Revichi27 and Reich28 also reported significant improvements in DLQI scores and in Bodily Pain and Social Functioning scales of the Short-Form 36 in patients treated with biologics. Norlin15 reported significant improvement in DLQI and EQ-5D scores in patients who switched from conventional treatment to Adalimumab, Etanercept, Infliximab, or Ustekinumab. Whether or not the early response seen in the secukinumab results is mirrored in the other biologics is unknown, as most trials report only their primary endpoint results, between 12 and 16 weeks.

Limitations

There were a number of limitations to this analysis. The results were from the first 12-week period of a phase 2 study and reflected short-term improvements with secukinumab. These results have now been be confirmed by phase 3 studies reflecting long-term effects.29

The analyses did not take into account the comorbidity of psoriatic arthritis. Fewer patients receiving placebo regimen had psoriatic arthritis (17.9 %) than patients receiving a secukinumab regimen (22.7 %-32.6 %).

Although Fisher's exact test indicated an advantage of all secukinumab regimens over placebo regimen, this approach did not account for baseline DLQI. The estimation techniques that did adjust for baseline DLQI performed inadequately, due to the limited spread of the dichotomized data. Alternatively, modeling DLQI total scores using a linear regression model could be possible, but the highly skewed data would require transformation. Results suggested that maximum likelihood estimation techniques were not appropriate for the analysis of these dichotomized DLQI response data.

Lack of precision indicated that these point estimates may not be generalizable to a wider population with psoriasis. However, estimate significance at the 1 % (monthly) and 5 % (early) levels for the primary analysis provided evidence that the advantage of these two regimens over placebo regimen was unlikely to be a chance occurrence.

This analysis provided statistical evidence that secukinumab treatment regimens are associated with significant improvements in the DLQI assessments over 12 weeks. The percentages of psoriasis patients reporting improvement in HRQoL at 12 weeks were higher in the early and monthly regimens than in the single and placebo regimens. There was improvement in all secukinumab regimens at week 4, which continued at week 12 in the monthly and early regimens. These results mirrored the improvements in PASI 75 and PASI 90 scores in the early and monthly regimens17, which were not observed in the single regimen. This demonstrates the value and importance of determining appropriate secukinumab treatment regimens to achieve significant improvement in HRQoL.

CONCLUSION

Study results suggested that moderate to severe plaque-psoriasis patients receiving multidose secukinumab regimens early in treatment have improved HRQoL compared with patients receiving placebo.

The findings from this have been confirmed in larger trials and further investigation of the relationship between secukinumab and HRQoL is ongoing.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source

This article was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. East Hanover, NJ, USA. Dr. Gelfand is supported by NIH/NIAMS grant K24 AR064310.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG (Novartis). Novartis develops and markets treatments for psoriasis. RTI Health Solutions (RTI-HS) was a paid consultant to Novartis for this study. S. Abeysinghe and D. McBride are full-time employees of RTI-HS, a research organization that provides consulting services to pharmaceutical organizations. N. Roskell is a full-time employee of CROS NT Ltd. but performed this work while employed by RTI Health Solutions. U. Mallya is a full-time employee of Sanofi, but performed this work while employed by Novartis. C. Papavassilis is a full-time employee of Novartis and hold stock and/or stock options in Novartis.

J. Gelfand has been an investigator for and receives grants from Amgen, Abbott, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Genentech, Janssen, and Pfizer. He is or has been a consultant for Amgen, Abbott, Novartis, Genentech, Janssen, Merck, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer.

Z. Qureshi has been an investigator for or receives grants from Amgen. He is or has been a consultant for Abbott, Janssen, Novartis, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. M. Augustin has served as consultant to or paid speaker for clinical trials sponsored by companies that manufacture drugs used for the treatment of psoriasis, including Abbott, Almirall, Amgen, Biogen Idec, Celgene, Centocor, Janssen-Cilag, Leo, Medac, MSD, Novartis, and Pfizer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Raychaudhuri SP, Farber EM. The prevalence of psoriasis in the world. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:16–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths CEM, Barker, Jonathan NWN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:263–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimball AB, Gladman D, Gelfand JM, et al. National Psoriasis Foundation clinical consensus on psoriasis comorbidities and recommendations for screening. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:1031–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmitt J, Meurer M, Klon M, Frick KD. Assessment of health state utilities of controlled and uncontrolled psoriasis and atopic eczema: a population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:351–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Augustin M, Krüger K, Radtke MA, et al. Disease severity, quality of life and health care in plaque-type psoriasis: a multicenter cross-sectional study in Germany. Dermatology. 2008;216:366–72. doi: 10.1159/000119415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krueger G. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 national psoriasis foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:280–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raho G, Koleva DM, Garattini L, Naldi L. The burden of moderate to severe psoriasis: an overview. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30:1005–13. doi: 10.2165/11591580-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, et al. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:401–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis--oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica. 1978;157:238–44. doi: 10.1159/000250839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Medicines Agency, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use [6 May 2013];Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products indicated for the treatment of psoriasis. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000398.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580034cf0.

- 11.Spandonaro F, Altomare G, Berardesca E, et al. Health-related quality of life in psoriasis: an analysis of Psocare project patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2011;146:169–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cozzani E, Borrini V, Pennella A, et al. The quality of life in Italian psoriatic patients treated with biological drugs. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:709–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schiffner R, Schiffner-Rohe J, Gerstenhauer M, et al. Willingness to pay and time tradeoff: sensitive to changes of quality of life in psoriasis patients? Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1153–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prinsen C, Korte J de, Augustin M, et al. Measurement of health-related quality of life in dermatological research and practice: Outcome of the EADV Taskforce on Quality of Life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1195–203. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norlin JM, Steen Carlsson K, Persson U, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Switch to biological agent in psoriasis significantly improved clinical and patient-reported outcomes in real-world practice. Dermatology. 2012;225:326–32. doi: 10.1159/000345715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffiths CEM. Biologics for psoriasis: current evidence and future use. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(Suppl 3):1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hueber W, Patel DD, Dryja T, et al. Effects of AIN457, a fully human antibody to interleukin-17A, on psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and uveitis. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:52ra72. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rich P, Sigurgeirsson B, Thaci D, et al. Secukinumab induction and maintenance therapy in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II regimen-finding study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:402–11. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shikiar R, Willian MK, Okun MM, et al. The validity and responsiveness of three quality of life measures in the assessment of psoriasis patients: results of a phase II study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:71. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert J, Dowlatshahi EA, La Brassinne M de, Nijsten T. A descriptive study of psoriasis characteristics, severity and impact among 3,269 patients: results of a Belgian cross sectional study (BELPSO). Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:231–7. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, et al. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994-2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:997–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norlin JM, Steen Carlsson K, Persson U, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Analysis of three outcome measures in moderate to severe psoriasis: a registry-based study of 2450 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:797–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, et al. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: What do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:659–64. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Augustin M, Alvaro-Gracia JM, Bagot M, et al. A framework for improving the quality of care for people with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(Suppl 4):1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shikiar R, Heffernan M, Langley RG, et al. Adalimumab treatment is associated with improvement in health-related quality of life in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a phase II randomized controlled trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18:25–31. doi: 10.1080/09546630601121060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Revicki DA, Menter A, Feldman S, et al. Adalimumab improves health-related quality of life in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis compared with the United States general population norms: results from a randomized, controlled Phase III study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:75. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reich K, Nestle FO, Papp K, et al. Improvement in quality of life with Infliximab induction and maintenance therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1161–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis--results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]