Abstract

Background

HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) infants are a growing population in sub-Saharan Africa, with higher morbidity and mortality than HIV-unexposed infants. HEU infants may experience increased morbidity due to breastfeeding avoidance.

Objective

We sought to describe the burden and identify predictors of hospitalization among HEU infants in the first year of life.

Methods

Using a retrospective cohort of HIV-infected mothers and their HEU infants in Nairobi, Kenya, we identified infants who were HIV-uninfected at birth and were followed monthly until last negative HIV test, death, loss to follow-up or study exit at one year of age. Incidence, timing and reason for hospitalization was assessed overall as well as stratified by feeding method. Predictors of first infectious disease hospitalization were identified using competing risk regression, with HIV acquisition and death as competing risks.

Results

Among 388 infants, 113 hospitalizations were reported [35/100 infant-years, 95% confidence interval (CI) 29–42]. Ninety hospitalizations were due to one or more infectious diseases [26/100 infant-years, 95%CI 21–32], primarily pneumonia (n=40), gastroenteritis (n=17) and sepsis (n=14). Breastfeeding was associated with decreased risk of infectious disease hospitalization [SHR=0.39 (95%CI 0.24–0.64)], as was time-updated nutritional status [SHR=0.73 (95%CI 0.61–0.89)]. Incidence of infectious disease hospitalization among formula-fed infants was 51/100 child-years (95%CI 37–70) compared to 19/100 child-years (95%CI 14–25) among breastfed infants.

Conclusion

Among HEU infants, breastfeeding and nutritional status were associated with reduced hospitalization during the first year of life.

BACKGROUND

An estimated 1.5 million HIV-infected women give birth in low- and middle-income countries annually1. In the absence of prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) interventions, 30–45% of infants born to HIV-infected mothers will become infected2; the remainder of children born to HIV-infected mothers are HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU). HEU children are a large and growing population3, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where the HIV epidemic is concentrated1. As PMTCT programs become more accessible and successful1, the population of HEU children is expected to continue to grow3. Several studies have shown increased mortality among HEU infants in the first year of life4–8. HEU infants had increased risk of serious infections in the first year of life in a small South African study,9 and increased risk of hospitalization and severe febrile illness in the Ugandan PROMOTE study10. The ZVITAMBO trial in Zimbabwe found increased risk of sick-child visits to clinic throughout the first year for HEU infants, as well as increased risk of hospitalization in the neonatal period4.

Increased morbidity and mortality among HEU infants may be due to a variety of maternal and infant immunologic and sociodemographic factors3. Breastfeeding avoidance by HIV-infected mothers in accordance with previous WHO guidelines, which recommended breastfeeding avoidance when alternative feeding was acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable and safe (AFASS)11 may also have contributed to poorer outcomes among HEU infants during the time these guidelines were in effect. We evaluated incidence and predictors of hospitalization among Kenyan HEU infants in the first year of life, with an emphasis on the effects of infant feeding method and nutritional status.

METHODS

The parent cohort study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board and the Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics and Research Committee. The current analysis was ruled exempt from ethics review as a secondary data analysis of a deidentified dataset.

Study design

We identified singleton and first-born twin infants who were confirmed to be HIV-uninfected at birth from a previously accrued cohort of HIV-infected mothers and their infants, details of which have been published previously12–14. Briefly, HIV-infected women were enrolled during pregnancy between 1999–2002 in Nairobi, Kenya and followed until one year postpartum. Sociodemographic information was collected at enrollment and maternal CD4 count and log10 HIV viral load were assessed at 32 weeks gestation. Participants received short-course zidovudine for PMTCT as was standard of care at the time of the study; mothers were counseled on infant feeding and the risk of HIV transmission via breast milk before electing to breastfeed or formula feed; for those choosing to breastfeed, exclusive breastfeeding for six months was recommended. Infants were examined by study physicians within 48 hours of delivery, at 2 weeks of age and then monthly until one year of age. Clinical care was provided by study physicians at sick-child visits. During scheduled visits, infants underwent a detailed clinical exam and growth assessment, and mothers gave a history that included timing of and reason for hospitalization, as well as feeding method since the last visit.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Incidence and timing of a) all-cause and b) infectious disease hospitalization (IDH), including repeat hospitalizations, were assessed using maternal report and study physician referral records; infants contributed person-time until last negative HIV test, death, loss to follow-up or study exit. Incidence of IDH was also assessed stratified by time-updated nutritional status (underweight vs. not underweight) and by feeding method: infants exclusively breastfed to six months vs. those never breastfed (formula-fed infants) and those who were breastfed for less than six months or had complementary feeding introduced before six months (mixed-fed infants). Univariate predictors of first IDH in the first year of life were identified using competing risk regression, with HIV acquisition and death as competing risks and robust standard errors. In sensitivity analyses, univariate predictors were adjusted for maternal HIV log10 viral load and CD4% at 32 weeks gestation, which were identified a priori as potential confounders. Dose response by categorical predictors was assessed using a test for trend in survival functions. All predictors were assessed at baseline with the exception of infant growth and feeding information, which were collected longitudinally.

Infant growth and nutritional status were assessed by WHO weight-for-age Z-score (WAZ) and length-for-age Z-score (LAZ). WAZ<-2 was considered underweight and LAZ<-2 stunted. Growth information was time-updated to reflect the WAZ and LAZ at the most recent visit prior to the visit when mothers reported hospitalization or an infant was referred to hospital. Lagged WAZ and LAZ were used in order to avoid spurious associations due to acute weight loss accompanying the illness for which an infant was hospitalized. Feeding information was not time-updated in the main analysis; infants were considered breastfed throughout if mothers reported breastfeeding at one or more study visits, and formula-fed if mothers never reported breastfeeding. Sensitivity analyses assessed the association between time-updated feeding method and hospitalization.

RESULTS

Study population

Mothers’ median age at enrolment was 25 years (IQR 22–28). 90% were married, 70% did not work outside the home, and 30% were primiparous. At 32 weeks gestation, mothers’ median HIV viral load was 4.7 log10 copies/ml (IQR 4.1–5.2), and median CD4 was 24% (IQR 18–30). Of 388 HEU infants, 23 acquired HIV at a median of 33 days (IQR 29–180) and 22 died at a median of 108 days (IQR 73–149). Of the remaining 343 infants, 310 (91%) completed 12 months of follow-up. Seventy-six percent of infants were breastfed for a median of 273 days (IQR 121–363). Mixed feeding was introduced at a median of 62 days (IQR 15–153) for breastfed infants; only 36% of breastfed infants were exclusively breastfed until six months of age as recommended to HIV-infected mothers electing to breastfeed.

Burden and causes of hospitalization

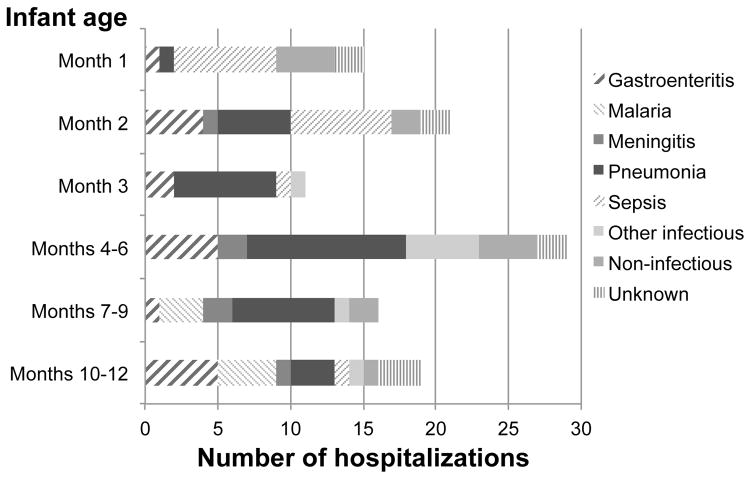

Incidence of all-cause hospitalization was 35/100 infant-years [95% confidence interval (CI) 29–42], representing 113 hospitalizations among 86 infants. Of the 113 hospitalizations, 38 were referrals by study physicians, and the remaining 75 were direct admissions to hospital or referrals from other clinics. Incidence of hospitalization was highest in the first three months of life. Duration of hospitalization was available for 92 cases; median duration of hospitalization was 5 days (IQR 3–10), and of 22 deaths in the cohort, 11 occurred among previously hospitalized children. Ninety hospitalizations among 70 infants were attributed to one or more infections [incidence 26/100 child-years, (95% CI 21–32)], primarily pneumonia (n=40, Figure 1), sepsis (n=18) and gastroenteritis (n=17). Fourteen hospitalizations were not due to infection; these were most commonly attributed to birth defects or birth complications (n=5), and 9 had no cause recorded.

Figure 1.

Frequency, timing and primary cause of hospitalizations among 388 HIV-exposed uninfected infants in the first year of life.

Competing risk regression

The analysis of infectious disease hospitalization (IDH) included 70 first hospitalizations and 16 competing events of infants dying or acquiring HIV without first being hospitalized. Maternal HIV log10 viral load and CD4% at 32 weeks gestation were not associated with IDH (Table 1), although greater than median viral load (>4.7 log10 copies/ml) was associated with a trend towards increased IDH [subhazard ratio (SHR)=1.5 (95% CI 0.93–2.6)]. Preterm birth, low birth weight and crowding in the home were not associated with IDH in the first year, although infants born preterm were at increased risk during the first two months (data not shown). Compared to formula feeding, ever breastfeeding was associated with 61% decreased risk of IDH [SHR=0.39 (95% CI 0.24–0.64), p<0.001]. Similarly, in a sensitivity analysis considering time-updated feeding information, current breastfeeding was associated with 62% reduced risk of IDH [SHR=0.38 (95% CI 0.22–0.65), p<0.001]).

Table 1.

Predictors of first infectious disease hospitalization in the first year of life among HIV-exposed uninfected infants. 388 mother-infant pairs made up the cohort and 70 infants were hospitalized one or more times due to infectious diseases. Subhazard ratios (SHR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were identified using competing risk regression, with HIV acquisition and death as competing risks. Unless otherwise noted, all estimates are unadjusted.

| Maternal / infant characteristics | na | SHR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal CD4% at 32 weeks gestation (per 5% increase) | 375 | 1.0 (0.89–1.2) |

| Maternal CD4% ≥ 20 at 32 weeks gestation | 317 | Ref. |

| Maternal CD4% <20 at 32 weeks gestation | 58 | 0.79 (0.46–1.4) |

| Maternal HIV viral load at 32 weeks (per log10 increase) | 348 | 1.1 (0.79–1.6) |

| HIV viral load ≤ 4.7 log10 at 32 weeks gestation | 170 | Ref. |

| HIV viral load >4.7 log10 at 32 weeks gestation | 174 | 1.5 (0.93–2.6) |

| Infant gestational age at birth ≥ 37 weeks | 320 | Ref. |

| Infant gestational age at birth <37 weeks | 21 | 1.8 (0.85–3.7) |

| Infant birth weight ≥ 2500 g | 353 | Ref. |

| Infant birth weight <2500 g | 21 | 1.4 (0.54–3.4) |

| No crowding in the home (≤3 people / room) | 296 | Ref. |

| Crowding in the home (>3 people / room) | 87 | 1.6 (0.93–2.6) |

| Infant formula-fed | 92 | Ref. |

| Infant breastfed | 295 | 0.39 (0.24–0.64) |

|

| ||

| Infant growth indicators at most recent visit | n | SHR (95% CI) |

|

| ||

| Weight-for-age Z-score (per standard deviation) | 384 | 0.72 (0.60–0.86) |

| Underweight (WAZ<-2) | 384 | 1.8 (0.85–3.7) |

| Height-for-age Z-score (per standard deviation) | 384 | 0.91 (0.82–1.0) |

| Stunted (Height-for-age Z-score<-2) | 384 | 1.1 (0.58–2.2) |

|

| ||

| Adjusted breastfeeding analyses | n | SHR (95% CI) |

|

| ||

| Ever breastfed | 348 | 0.38 (0.23–0.64) |

| Maternal HIV viral load at 32 weeks (per log10) | 1.1 (0.77–1.5) | |

| Ever breastfed | 370 | 0.38 (0.23–0.65) |

| Weight-for-age Z-score at most recent visit (per standard deviation) | 0.78 (0.65–0.93) | |

For continuous and time-varying exposures, n represents mother-infant pairs contributing data to each comparison; for categorical variables, n represents mother-infant pairs in each category.

While height-for-age Z-score (HAZ) was not associated with subsequent IDH, better nutritional status, as indicated by higher weight-for-age Z-score (WAZ), was associated with 28% decreased risk of IDH per standard deviation [SHR=0.72 (95% CI 0.60–0.86)] within the subsequent time period. When the effect of time-varying WAZ on IDH was adjusted for feeding method, both remained independently significant. All estimates were unaffected by adjustment for maternal CD4% or HIV viral load at 32 weeks gestation (data not shown).

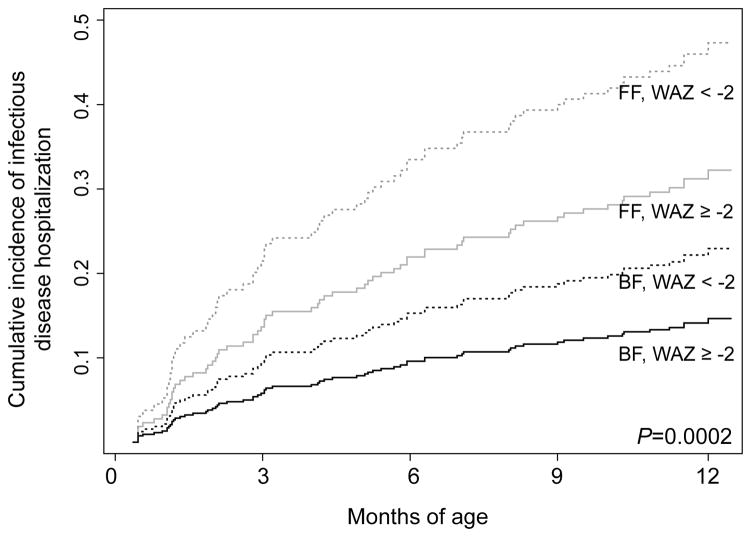

Allowing for repeat hospitalizations, overall incidence of IDH was 51/100 child-years (95% CI 37–70) among formula-fed infants and 19/100 child-years (95% CI 14–25) among breastfed infants. There was no difference in incidence among infants exclusively breastfed for six months [18/100 child-years (95% CI 11–30)] and those mixed-fed or breastfed for less than six months [20/100 child-years (95% CI 14–28)]. When incidence of IDH was stratified by feeding method and underweight (WAZ<-2), a strongly significant dose-response was observed (Figure 2, p=0.0002).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of infectious disease hospitalization among 388 HIV-exposed, uninfected infants stratified by infant feeding (formula-fed (FF) vs. breastfed (BF)) and infant weight (underweight (weight-for-age Z-score (WAZ)<-2) vs. not underweight (WAZ ≥-2)). P-value is obtained from a test for trend in survival functions.

DISCUSSION

We found a substantial burden of hospitalization in our cohort of HIV-exposed uninfected infants, primarily for infectious diseases. The incidence of hospitalization we observed, 35/100 infant-years, is somewhat higher than that reported in a South African study of HEU (23/100 child-years)15, which may be explained by access to safe public drinking water for all participants in that study. The proportion of infants hospitalized is also higher than that in a Zambian study in which 39 of 620 HEU infants had been hospitalized by 4 months of age16. Consistent with prior studies of HEU infants in Malawi17 and Zambia16, however, most hospitalizations were due to pneumonia, sepsis and gastroenteritis; the combined incidence of hospitalization due to pneumonia, severe febrile illness and diarrhea in our study is comparable to that reported in the Malawian BAN study17.

We observed substantially lower risk of hospitalization among breastfed infants than non-breastfed infants, which is consistent with several prior studies of HEU infants. In a South African study in which mothers self-selected feeding method, a lower risk of hospitalization was observed among breastfed infants in the first 14 weeks of life, but this difference was no longer significant by 6 months18. The BAN study in Malawi, in which all infants breastfed, found increased risk of morbidity after weaning4; the same effect was observed in a Zambian trial of early abrupt weaning19,20. Gastroenteritis hospitalization was associated with lack of breastfeeding in an Indian study21 and with early weaning in a Malawian study22.

While our study noted impact of any breastfeeding, other studies have also noted strong protective effects of exclusive breastfeeding23,24. Rates of exclusive breastfeeding were low in our cohort and duration was short, limiting our ability to compare exclusively breastfed infants and mixed-fed infants. In addition, there was some inconsistent reporting, with mothers reporting breastfeeding cessation and later reporting a return to breastfeeding. This may have been due to social desirability bias, with mothers wishing to appear to comply with study counseling recommending breastfeeding cessation at the time complementary feeding was introduced. Despite the limitations of the time-updated data, the strength of the association between feeding method and hospitalization was comparable when current breastfeeding was considered.

Maternal CD4 and HIV viral load during pregnancy have been associated with risk of severe morbidity among HEU infants in several African studies4,16 and a large French cohort.25 This may be due to infant immune abnormalities following HIV exposure,5 reduced maternal-derived antibody levels at birth26, or to higher maternal morbidity and mortality leading to increased pathogen exposure and compromised care of the infant.3,8 We found no association between infant hospitalization and maternal CD4 in our study, possibly because CD4 counts and CD4% at 32 weeks gestation do not accurately reflect maternal health at delivery or postpartum. Time-updated CD4 would have been a preferable measure, but these data were missing in a large number of cases. We also did not observe an association between continuous maternal HIV viral load during pregnancy and infant hospitalization, although we observed a trend toward increased risk of IDH for children of mothers with higher than median viral loads during pregnancy; our study lacked power to detect an association of this magnitude.

Our observation that low WAZ was associated with increased rates of hospitalization is consistent with prior studies.27 Children of HIV-infected mothers are at high risk of growth failure28, and this association has been related to breastfeeding cessation in a Zambian cohort29. Interestingly, adjustment for feeding method did not alter the association between WAZ and hospitalization in our cohort, and a dose response was observed when the combined effect of underweight and breastfeeding was analyzed.

Our study had several limitations. Because our cohort lacked an HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) control group, we are not able to determine whether HEU infants were at higher risk of hospitalization than HUU infants in our setting; conflicting data on this question exist4,6. Two thirds of infant hospital referrals were made by physicians outside our study clinics, meaning that reasons recorded were based on maternal report and may be imperfectly recalled. In focusing on hospitalization due to infectious disease, we excluded nine hospitalizations for which the cause was unknown; it is possible that these hospitalizations were due to infectious causes and should have been included in the competing risk regression analysis. Lastly, our study was conducted prior to the introduction of new PMTCT guidelines (Option B/B+)30, in which mothers receive lifeling highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) starting during pregnancy or breastfeeding. These guidelines may result in improved HEU outcomes via improved maternal immunity, transferred immune responses, and decreased maternal morbidity. Strengths of our study include cohort follow-up from birth through the first year of life, high retention rate, serial assessment of growth and morbidity by study physicians, and standardized collection of hospitalization data. For infants who acquired HIV during the study, timing of HIV infection was known, enabling us to include hospitalization history prior to HIV acquisition for these infants.

CONCLUSION

The most recent WHO guidelines regarding infant feeding support breastfeeding for all mothers with HIV, along with lifelong antiretroviral therapy started during pregnancy or breastfeeding.30 These guidelines aim to both reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV and improve maternal immunologic and virologic indicators, meaning that other correlates of infant hospitalization may emerge in future studies among HEU infants. Our results suggest the new feeding guidelines may reduce serious morbidity and hospitalization among HEU infants, and that the promotion of safe breastfeeding and improved nutrition will remain important for HEU infant health.

Well Established

Infant feeding recommendations for HIV-infected women must balance the benefits of breastfeeding against the risk of transmission of HIV via breast milk. WHO guidelines have undergone several revisions and now recommend breastfeeding for HIV-infected mothers in resource-limited settings.

Newly Expressed

Among HIV-exposed uninfected infants in our retrospective Kenyan cohort, breastfeeding was associated with decreased risk of hospitalization due to infectious diseases in the first year of life. This decreased risk was observed among both exclusively breastfed and mixed-fed infants.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The parent study was funded by US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant R01 HD-23412). KHA and GJS were supported in part by NIH K24 HD054314, KHA was supported by NIH Interdisciplinary Training in Cancer Research, T32 CA080416 and by a Trainee Support Grant from the Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) under NIH award number P30AI027757. JS and KHA were supported in part by a New Investigator Award from CFAR under NIH award number P30AI027757. JS was supported by NIAID K01AI087369. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.WHO. [Accessed June 15, 2015];HIV/AIDS Fact Sheet No. 360. 2014 http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs360/en/

- 2.De Cock KM, Fowler MG, Mercier E, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in resource-poor countries: translating research into policy and practice. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(9):1175–1182. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filteau S. The HIV-exposed, uninfected African child. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH. 2009;14(3):276–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koyanagi A, Humphrey JH, Ntozini R, et al. Morbidity among human immunodeficiency virus-exposed but uninfected, human immunodeficiency virus-infected, and human immunodeficiency virus-unexposed infants in Zimbabwe before availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2011;30(1):45–51. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181ecbf7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afran L, Garcia Knight M, Nduati E, Urban BC, Heyderman RS, Rowland-Jones SL. HIV-exposed uninfected children: a growing population with a vulnerable immune system? Clinical and experimental immunology. 2014;176(1):11–22. doi: 10.1111/cei.12251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landes M, van Lettow M, Chan AK, Mayuni I, Schouten EJ, Bedell RA. Mortality and health outcomes of HIV-exposed and unexposed children in a PMTCT cohort in Malawi. PloS one. 2012;7(10):e47337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurewa EN, Gumbo FZ, Munjoma MW, et al. Effect of maternal HIV status on infant mortality: evidence from a 9-month follow-up of mothers and their infants in Zimbabwe. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2010;30(2):88–92. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaba B, Whitworth J, Marston M, et al. HIV and mortality of mothers and children: evidence from cohort studies in Uganda, Tanzania, and Malawi. Epidemiology. 2005;16(3):275–280. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000155507.47884.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slogrove A, Reikie B, Naidoo S, et al. HIV-Exposed Uninfected Infants are at Increased Risk for Severe Infections in the First Year of Life. Journal of tropical pediatrics. 2012 doi: 10.1093/tropej/fms019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marquez C, Okiring J, Chamie G, et al. Increased Morbidity in Early Childhood Among HIV-exposed Uninfected Children in Uganda is Associated with Breastfeeding Duration. Journal of tropical pediatrics. 2014;60(6):434–441. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmu045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. Guidelines on HIV and infant feeding: principles and recommendations for infant feeding in the context of HIV and a summary of evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.John-Stewart GC, Mbori-Ngacha D, Payne BL, et al. HV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and breast milk HIV-1 transmission. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2009;199(6):889–898. doi: 10.1086/597120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asbjornsdottir KH, Slyker JA, Weiss NS, et al. Breastfeeding is associated with decreased pneumonia incidence among HIV-exposed, uninfected Kenyan infants. AIDS. 2013;27(17):2809–2815. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000432540.59786.6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gichuhi C, Obimbo E, Mbori-Ngacha D, et al. Predictors of mortality in HIV-1 exposed uninfected post-neonatal infants at the Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East African medical journal. 2005;82(9):447–451. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v82i9.9334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkatesh KK, de Bruyn G, Marinda E, et al. Morbidity and mortality among infants born to HIV-infected women in South Africa: implications for child health in resource-limited settings. Journal of tropical pediatrics. 2011;57(2):109–119. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmq061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhn L, Kasonde P, Sinkala M, et al. Does severity of HIV disease in HIV-infected mothers affect mortality and morbidity among their uninfected infants? Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2005;41(11):1654–1661. doi: 10.1086/498029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kourtis AP, Wiener J, Kayira D, et al. Health outcomes of HIV-exposed uninfected African infants. AIDS. 2013;27(5):749–759. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835ca29f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kindra G, Coutsoudis A, Esposito F, Esterhuizen T. Breastfeeding in HIV exposed infants significantly improves child health: a prospective study. Maternal and child health journal. 2012;16(3):632–640. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0795-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fawzy A, Arpadi S, Kankasa C, et al. Early weaning increases diarrhea morbidity and mortality among uninfected children born to HIV-infected mothers in Zambia. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011;203(9):1222–1230. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhn L, Sinkala M, Semrau K, et al. Elevations in mortality associated with weaning persist into the second year of life among uninfected children born to HIV-infected mothers. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;50(3):437–444. doi: 10.1086/649886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh HK, Gupte N, Kinikar A, et al. High rates of all-cause and gastroenteritis-related hospitalization morbidity and mortality among HIV-exposed Indian infants. BMC infectious diseases. 2011;11:193. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kafulafula G, Hoover DR, Taha TE, et al. Frequency of gastroenteritis and gastroenteritis-associated mortality with early weaning in HIV-1-uninfected children born to HIV-infected women in Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(1):6–13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bd5a47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rollins NC, Ndirangu J, Bland RM, Coutsoudis A, Coovadia HM, Newell ML. Exclusive breastfeeding, diarrhoeal morbidity and all-cause mortality in infants of HIV-infected and HIV uninfected mothers: an intervention cohort study in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. PloS one. 2013;8(12):e81307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bork KA, Cournil A, Read JS, et al. Morbidity in relation to feeding mode in African HIV-exposed, uninfected infants during the first 6 mo of life: the Kesho Bora study. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2014;100(6):1559–1568. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.082149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taron-Brocard C, Le Chenadec J, Faye A, et al. Increased risk of serious bacterial infections due to maternal immunosuppression in HIV-exposed uninfected infants in a European country. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2014;59(9):1332–1345. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farquhar C, Nduati R, Haigwood N, et al. High maternal HIV-1 viral load during pregnancy is associated with reduced placental transfer of measles IgG antibody. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(4):494–497. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000168179.68781.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):243–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muhangi L, Lule SA, Mpairwe H, et al. Maternal HIV infection and other factors associated with growth outcomes of HIV-uninfected infants in Entebbe, Uganda. Public health nutrition. 2013;16(9):1548–1557. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arpadi S, Fawzy A, Aldrovandi GM, et al. Growth faltering due to breastfeeding cessation in uninfected children born to HIV-infected mothers in Zambia. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2009;90(2):344–353. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO. Programmatic Update: Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating Pregnant Women and Preventing HIV Infection in Infants. 2012 Apr;2012 [Google Scholar]