Abstract

Objective

To investigate the role of Smad3 as a regulator of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1-mediated cell activities associated with fibrosis in normal human vocal fold fibroblasts. We also sought to confirm the temporal stability of Smad3 knockdown via siRNA. Vocal fold fibroblasts were employed to determine the effects of Smad3 knockdown on TGF-β1-mediated migration and contraction as well as regulation of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF). We hypothesized that Smad3 is an ideal candidate for therapeutic manipulation in vivo based on its role in fibrosis.

Study Design

In vitro

Methods

Knockdown of Smad3 via siRNA was performed in our normal human vocal fold cell line. Three-dimensional collagen gel contraction and scratch assays were employed to determine the role of Smad3 on TGF-β1-mediated contraction and migration, respectively. The role Smad3 in the induction of CTGF was characterized via SDS-Page. The effects of Smad3 signaling on Smad7 mRNA and protein were also quantified.

Results

Smad3 knockdown was temporally stable up to 72 hours (p<0.001). Smad3 knockdown diminished TGF-β1-mediated collagen gel contraction and migration. Smad3 knockdown also blunted induction of CTGF, but had no effect on TGF-β1-mediated Smad7 mRNA or protein induction.

Conclusion

TGF-β1 stimulated pro-fibrotic cell activities in our cell line and these actions were largely reduced with Smad3 knockdown. These data provide continued support for therapeutic targeting of Smad3 for vocal fold fibrosis as it appears to regulate the fibrotic phenotype.

Keywords: Voice, vocal fold, fibrosis, Smad3, TGF-β, scar

INTRODUCTION

The biophysical demands placed upon the vocal fold (VF) mucosa are profound and place the tissue at increased risk for long-term architectural changes associated with the inherent wound healing response. This response is complex involving multiple cell types as well as extracellular matrix. Recently, several laboratories provided substantive data regarding the processes underlying vocal fold wound healing with the ultimate goal of improved therapies to both avoid and/or treat vocal fold fibrosis. Given that the vocal fold mucosa is subjected to trauma associated with phonation with minimal changes to the vocal fold structure at baseline, a threshold likely exists with regard to the type and/or duration of injury that leads to the fibrotic tissue phenotype. Although this threshold has not been characterized and is likely variable across individuals, our laboratory and others have focused on key biochemical triggers responsible for this amplified wound healing response yielding tissue fibrosis and ultimately, aberrant phonatory physiology.

In this regard, TGF-β1 has been identified as one key mediator of fibrosis and is ubiquitous in both uninjured and injured tissue. TGF-β1 regulates both wound healing in general, and more specifically, the development of fibrosis through its interactions with mesenchymal cells. TGF-β1 affects numerous fibroblast activities including proliferation, adhesion, migration, apoptosis, and the production, degradation, and accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. Relevant to fibrosis, TGF-β1 stimulates fibroblasts to produce large amounts of extracellular matrix (ECM) including collagen and proteoglycans; it is implicated in excessive ECM deposition across numerous pathological fibrotic conditions including in the liver, lung, kidney, skin, heart, and arterial walls.1–8 Several laboratories including ours have implicated TGF-β1 as a mediator of VF scar.9,10

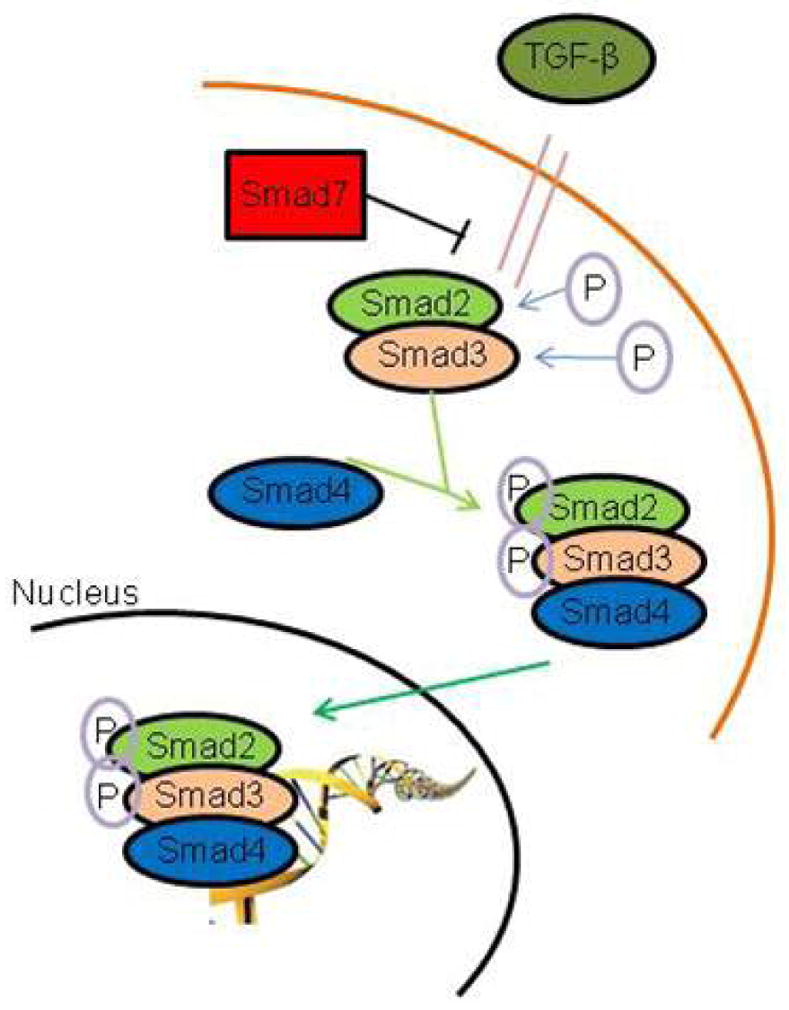

The actions of TGF-β1 are mediated via a unique signaling pathway, providing ample targets for intervention. Upon TGF-β1 binding to the cell surface receptor, the Smad family of proteins is phosphorylated leading to heterodimerization and nuclear translocation to regulate transcription (Figure 1). Activated Smads have been implicated in a variety of fibrotic processes suggesting that Smad activation plays a central role in both collagen production and accumulation in these diseases. Preliminary investigation by our laboratory confirmed upregulation of Smad3 mRNA following acute vocal fold injury.11 Globally, we hypothesize that Smad3 is a master regulator of fibrosis, and manipulation of Smad3 via RNA-based therapies holds significant clinical promise. Specifically, the loss of Smad3 has been shown to interfere with TGF-β1-mediated induction of genes for collagens and TIMPs, and Smad3-null mice are resistant to radiation induced cutaneous fibrosis, bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic fibrosis, glomerular fibrosis, and many other fibrotic conditions.12 Our laboratory recently performed direct injections of small inhibitor (si)RNA targeting Smad3 siRNA into rabbit vocal fold mucosa and therapeutic RNA interference is increasing in popularity across tissue systems and disease processes.13 In the current study, we sought to further describe the role of Smad3 as a mediator of the fibrotic phenotype in our normal human vocal fold fibroblast cell line in vitro based on our global hypothesis that Smad3 is a physiologically-relevant target for anti-fibrotic therapies in the vocal folds.

Figure 1.

Schematic of TGF-β signaling via Smad phosphorylation and nuclear translocation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Model

All experiments employed the immortalized human vocal fold fibroblast cell line created in our laboratory, referred to as HVOX.14 This line has been shown to stable through multiple population doublings; the current experiments employed cells in passages 20–30. All cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotic/antimycotic. Recombinant human transforming growth factor-β1 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) was employed in all experiments.

Transfection

As described previously by our laboratory,11 HVOX were grown to 60–80% confluence and treated with serum-free media overnight prior to experimentation. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and treated with Opti-MEM media with 10% fetal bovine serum (no antibiotic/antimycoticl) and Lipofectamine 2000 (1mg/mL) and siRNA for either Smad3 or nonsense sequence. Cells were treated with this complex and gently agitated for 6 hours. The transfection media was then removed and replaced with fresh media containing TGF-β1, when appropriate.

SDS-PAGE

At the experimental endpoint, cells were washed twice with cold PBS and a cell scraper was employed to free the cells from the plates. The cells were then resuspended in a 1.5ml tube and centrifuged at 3000rpm for 3 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was aspirated and the pellet was then lysed via Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with Halt Protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), 0.5M EDTA Solution 100x (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), and Calyculin A (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) on ice for 10 minutes. The tubes were then centrifuged at 14,000rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C and transferred to fresh tube. Total protein content was quantified with Pierce™ 660nm Protein Assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and a Synergy H1 Hybrid Reader (BioTek®, Winooski, VT) employing the manufacturer standard protocol. SDS-PAGE was then run via standard protocol and then transferred overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then blocked in non-fat milk and incubated with the primary antibody (CTGF, Smad7, or GAPDH; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:1000) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then treated with the secondary antibody Anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) for 1 hour at room temperature and then developed using chemiluminescent film.

Collagen Contraction

PureCol® (Advanced BioMatrix, San Diego, CA) collagen gels were made using the standard protocols.15,16 The pH was adjusted to 7.2–7.5 and the gel was dispensed inside 0.5″ Teflon rings (Cannon Gasket Inc., Fontana, CA) and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C to allow gelation. HVOX cells were seeded onto the gels at a concentration of 3x10^4 cells in 200 μL (1.5x10^5/mL) and incubated for 2 hours. The gels were then treated with 2mL of media supplemented with 5 % FBS+/− TGF-β (20ng/mL; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The Teflon washers were then carefully removed and the gels were freed from the underlying surface of the cell culture plate. Gels were imaged immediately upon treatment and then again at 6 hours with a digital, 8-megapixel camera. Changes in collagen gel area were analyzed using ImageJ® (National Institutes of Health).

Cell Migration/Scratch Assay. Cell migratory rate was quantified via standardized techniques previously described by our laboratory.14,17 HVOX were grown in T25 culture dishes until 100% confluent. The cells were then transfected using standard transfection protocols, see above. Using a small pipette tip, a gentle scratch was made laterally across the T25 from one end to the other. Transverse lines with a marker were drawn on the bottom of the T25 to serve as a reference. Cells were supplemented with 2ml DMEM with 5% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) +/− TGF-β1. The scratch was photographed using a Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope with an attached C mount Morrell® HDMI-02 camera. The cells were imaged at 4x magnification from 0 and 8 hours. The denuded area was then quantified in pixels using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). The migratory rate was then calculated as: initial area−final area=δarea/8 hours.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) was extracted from HVOX cells using the RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen®, Venlo, Netherlands) under standard protocol and then reverse transcribed using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). Quantitative PCR was run by using the TaqMan Gene Expression kit (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA) and the StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). Primer probes for Samd3 (Hs00969210_m1), Smad7 (Hs00998193_m1), and GAPDH (Hs02758991_g1) as an exogenous control were purchased from Life Technologies (Norwalk, CT).

Statistical Analyses

All experiments were performed in triplicate, at least. Information regarding the number of independent experiments is provided on each figure. For all analyses, the dependent variable of interest was subjected to a One Way Analysis of Variance at p=0.05. If the main effect was significant, post-hoc comparisons were performed via the Tukey method (p=0.05). All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software version 22.

RESULTS

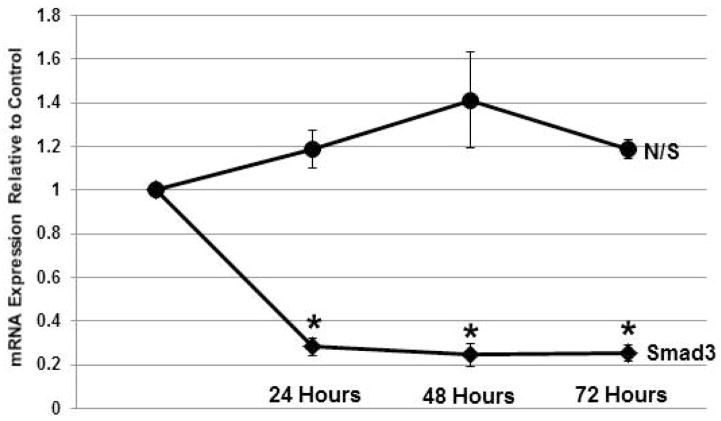

Smad3 knockdown is efficient and prolonged with siRNA

Treatment of HVOX cells with transfection media for 6 hours yielded consistent and efficient Smad3 knockdown as previously reported by our laboratory.11 The main effect for knockdown was significant (p<0.001). At 24 hours, knockdown was ~80% as previously described by our laboratory. This level of knockdown was maintained through 72 hours post transfection as confirmed via post-hoc pairwise comparisons (Figure 2). Nonsense siRNA had no statistically-significant effect on Smad3 mRNA expression in our cells.

Figure 2.

Temporal stability of Smad3 knockdown with siRNA compared to nonsense sequence over 72 hours following transfection (n=3; *p<0.05).

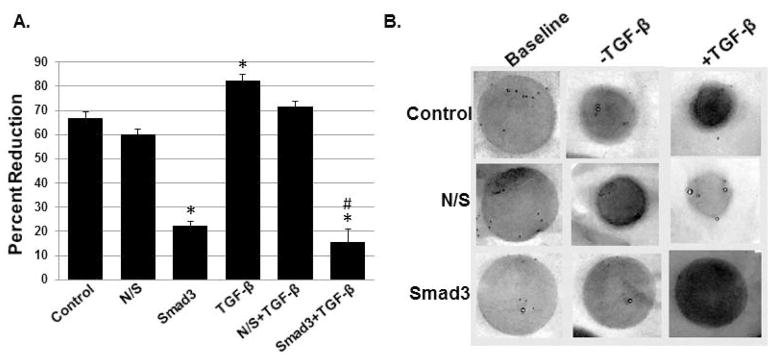

Smad3 knockdown blunted TGF-β-mediated collagen gel contraction

The main effect for contraction was significant (p<0.000; Figure 3A. Smad3 knockdown reduced collagen gel contraction at baseline by ~65%; this reduction was statistically significant (p<0.001). In contrast, TGF-β1 (10ng/mL) stimulated a statistically-significant increase in the contractile phenotype (p=0.024). This TGF-β-mediated response was reduced to levels similar to Smad3 knockdown without TGF-β1 treatment; this reduction was significant when compared to both control (p<0.001) and TGF-β1 treatment (p<0.001). Nonsense siRNA had no effect on the contractile phenotype in our cells. Representative images are shown in Figure 3B.

Figure 3.

The effects of TGF-β1 on three-dimensional collagen gel contraction (n=4; A; mean+/−SEM). TGF-β1 stimulated a statistically-significant increase in the contractile phenotype (p=0.024). This response was blunted by Smad3 knockdown (*p<0.05 relative to control; #p<0.05 relative to TGF-β1 stimulation). Representative gels are shown in B.

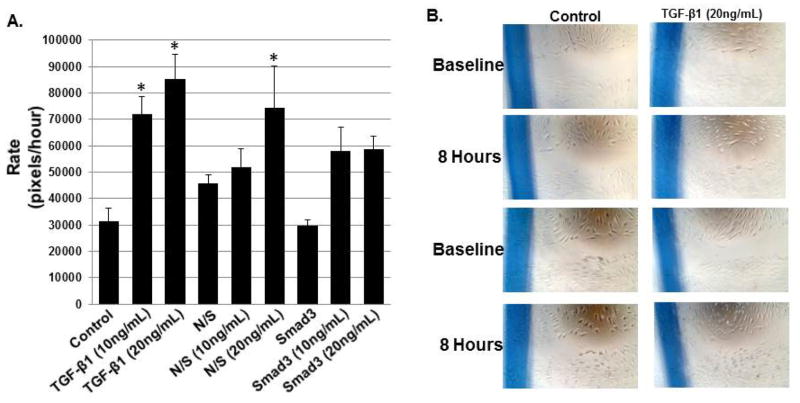

Smad3 knockdown did not affect TGF-β1-mediated cell migration

As shown in Figure 4, TGF-β1 at concentrations of 10 and 20ng/mL stimulated cell migration. The main effect for migration was significant (p<0.001). In the Smad3 knockdown condition, however, TGF-β1 at both concentrations stimulated a qualitative increase in migratory rate. This increase, however, did not achieve statistical significance (p=0.347 at 10ng/mL and p=0.319 at 20ng/mL).

Figure 4.

The effects of TGF-β1 on cell migration (A; mean+/−SEM). TGF-β1 had a dose-dependent effect on cell migration at both 10 and 20ng/mL (p=0.031 and p=0.002, respectively). Migratory rate increased in response to TGF-β1 in the context of Smad3 knockdown; this response, however, was not statistically significant when compared to control/untreated cells (p=0.347 at 10ng/mL and p=0.319 at 20ng/mL). Representative images are shown in B (nonsense siRNA not shown).

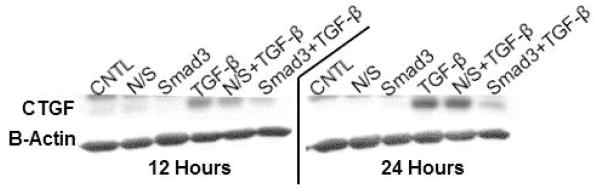

Smad3 knockdown limits TGF-β-mediated CTGF translation

Although CTGF protein was observed at baseline (e.g., control), marked upregulation of CTGF was observed in response to TGF-β1 (10ng/mL) at both 12 and 24 hours. As shown in Figure 5, CTGF protein levels were below control levels in response to Smad3 knockdown. Nonsense siRNA had no effect on CTGF protein levels.

Figure 5.

Representative SDS-PAGE gels probed for CTGF at 12 and 24 hours. TGF-β1 stimulated CTGF expression and this response was attenuated by Smad3 knockdown at both time points.

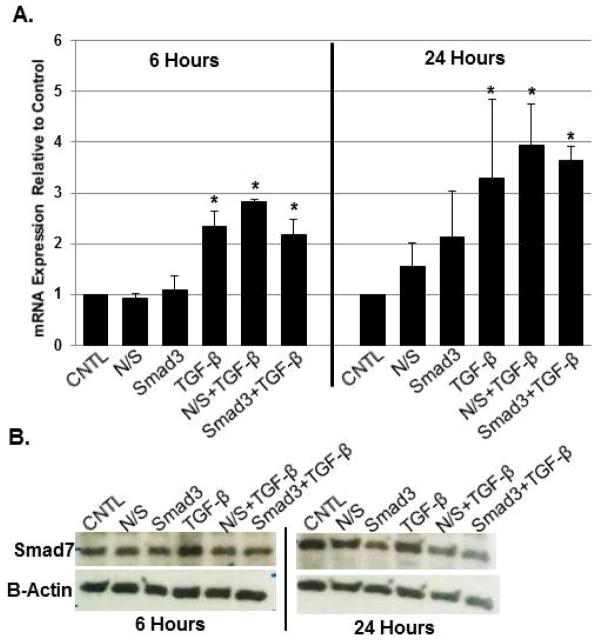

Smad3 knockdown altered Smad7 translation in response to TGF-β1

As noted previously by our laboratory,14 TGF-β1 (10ng/mL) stimulated increased in Smad7 mRNA expression and translation at both 6 and 24 hours; the main effect was significant (p<0.001 and p=0.002, respectively). Neither Smad3 nor nonsense siRNA reduced Smad7 transcription at either time point (Figure 6A; p=0.939 and p=0.995, respectively). Qualitatively, however, a slight decrease in Smad7 protein was observed at both time points (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Smad7 mRNA expression in response to Smad3 knockdown +/− TGF-β1 at both 6 and 24 hours (A; *p<0.05; n=3; mean+/−SEM); Smad7 mRNA expression increased in response to TGF-β1. Smad3 knockdown had little effect on this inherent anti-fibrotic response, as confirmed via protein analysis (B; representative gel).

DISCUSSION

Vocal fold scar continues to pose a profound clinical quandary as it can affect both glottic closure as well as overall mucosal pliability. Treatments, to date, have largely been directed at the former. The identification of key biochemical triggers responsible for the fibrotic vocal fold tissue phenotype is critical to the development of novel, physiologically-based therapeutics for this challenging patient population to direct tissue healing towards a more regenerative, less fibrotic outcome. Data across tissue systems including the vocal folds implicate TGF-β1 and more specifically, Smad3 as a master regulator of fibrosis. Our laboratory hypothesizes that therapeutic targeting of Smad3 will yield substantive change in the response to injury in the vocal folds.

In the current study, we sought to build upon on preliminary work describing the in vivo and in vitro effects of knocking down Smad3 gene expression via siRNA. Specifically, we sought to confirm temporal stability of Smad3 knockdown in our immortalized, normal human vocal fold fibroblast cell line. Transfection of these cells with siRNA for Smad3 lead to prolonged knockdown for 72 hours. RNA interference or RNAi with siRNA is a method for gene silencing triggering sequence-specific mRNA degradation. These techniques have become a useful tool to knock down the endogenous expression levels of specific genes and to then observe effects of this altered expression on individual cells.18 Modification of gene expression in the local tissue environment, such as the vocal folds, is critical for optimizing and individualizing cell therapies, eventually, for patients. Efficient and temporally-prolonged knockdown in our cell line are encouraging preliminary steps in this regard.

TGF-β1 exerts its pro-fibrotic effects via both direct and indirect mechanisms via induction of secondary pro-fibrotic mediators including connective tissue growth factor (CTGF). CTGF has been implicated as a downstream mediator of TGF-β1-induced fibroplasia due to its effects on fibroblasts.19 Interestingly, the precise role of CTGF in the vocal fold fibrosis has not been elucidated to date. However, CTGF mRNA expression in vocal fold fibroblasts appears responsive to injury associated prolonged exposure to laryngopharyngeal reflux.20 Regardless, CTGF induction via TGF-β1 in our cell line was Smad3-dependent as has been described in other cell types including human renal proximal tubule epithelial cells,21 suggestive that Smad3 mediates both the direct and indirect mechanisms underlying TGF-β1-mediated fibrosis.

Several in vitro cell activities are thought to be related to fibrosis in vivo, beyond extracellular matrix metabolism, including contraction and cell migration. Our data suggest that Smad3 altered the inherent cell response to exogenous TGF-β1 with regard to these fundamental cell activities. With regard to contraction, the contractile properties of vocal fold fibroblasts have not been described previously. Several studies, however, employed contraction as a dependent variable related to fibrosis in the subglottis.15,16,22,23 Contraction by fibroblasts is largely dictated by actin cytoskeletal forces generated inside the cells. As wound healing progresses, fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts increases these contractile forces due to up-regulation of α-smooth muscle (SM) actin.24 Fibrosis is characterized by prolonged myofibroblast presence and activity in the wound bed. Therefore, increased gel contraction in vitro is likely indicative of a fibrotic tissue phenotype in vivo. In our cell line, Smad3 knockdown limited TGF-β1-mediated collagen gel contraction. The effect on cell migration is a bit more nuanced and subtle. TGF-β1 increased cell migration even in the context of Smad3 knockdown; however, this increase did not achieve statistical significance. The role of Smad3 in cell migration has not been previously reported and warrants further investigation.

The response to injury is complex and the TGF-β signaling pathway involves an inherent anti-fibrotic feedback loop. As noted previously, Smad2 and 3 are receptor-activated or pathway-restricted (R-Smads) proteins directly activated by TGF-β. TGF-β1binding to the receptor phosphorylates R-Smads leading to heterodimerization with Smad4 and this complex translocates to the nucleus to regulate transcription. In addition, the system includes homologs to R-Smads that function as competitive inhibitors of Smad activation, namely Smad7. Constitutive Smad2, Smad3, and Smad7 mRNA expression in vocal fold fibroblasts was described by our laboratory previously.14 In the current study, we sought to determine the effects of altered Smad3 signaling on Smad7 mRNA and protein expression. In our cell line, induction of Smad7 does not appear to be Smad3-dependent. This finding is encouraging as it appears vocal fold fibroblasts maintain this inherent anti-fibrotic mechanism in the context of exogenous regulation of profibrotic gene expression. In the case of scar or keloids in the skin, a relative imbalance skewed towards pro-fibrotic mediators at the expense of anti-fibrotic mediators dictates directs fibroplastic fibroblast activity.25 As such, our data are encouraging as Smad3 knockdown does not appear to contribute to this imbalance.

In vitro investigation is not without limitation and caution should be taken with data of this sort. Beyond the inherent, contrived nature of in vitro experimentation, our cell line was acquired from a healthy woman with no known vocal fold pathology. One may hypothesize that a “normal” cell line may, in fact, respond quite differently to exogenous mediators of wound healing than a cell line obtained from actual fibrotic tissue. With these limitations in mind, we remain optimistic regarding the role of Smad3 in mediating tissue fibrosis. Data from the current study provide further foundation for continued investigation to eventually develop physiologically-based, therapies for millions of patients.

CONCLUSION

Smad3 consistently regulates in vitro TGF-β1-mediated cellular activities in our normal vocal fold fibroblast cell line that are thought to be consistent with fibroplasia in vivo. Knockdown of Smad3 via siRNA is consistent and temporally prolonged. Cumulatively, these data continue to suggest that RNA-based therapeutics targeting Smad3 may hold significant clinical promise.

Acknowledgments

A debt of gratitude is owed to Dr. Nao Hiwatashi for technical assistance and scientific review.

The work contained in this manuscript was funded by the National Institute for Deafness and Other Communication Disorders/National Institutes of Health (RO1 DC013277; PI: Branski)

Footnotes

Portions of data contained in this manuscript were accepted for podium presentation at the American Laryngological Association/Combined Otolaryngology Spring Meeting, Boston, MA, April 19, 2015.

No authors have any conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

Level of Evidence. N/A

References

- 1.Woodley DT, O’Keefe EJ, Prunieras M. Cutaneous wound healing: A model for cell-matrix interactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:420–433. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)80005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varga J, Jimenez SA. Stimulation of normal human fibroblast collagen production and processing by transforming growth factor-beta. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1986;138:974–980. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(86)80591-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozbilgin MK, Inan S. The roles of transforming growth factor type beta (3) (TGF-beta(3)) and mast cells in the pathogenesis of scleroderma. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22:189–195. doi: 10.1007/s10067-003-0706-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma LJ, Yang H, Gaspert A, et al. Transforming growth factor -beta-dependent and -independent pathways of induction of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in beta6(−/−) mice. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1261–1273. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63486-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massague J, Chen YG. Controlling TGF-beta signaling. Genes Dev. 2000;14:627–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB. 2004;18:816–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Border WA, Noble NA. Transforming growth factor beta in tissue fibrosis. N Eng J Med. 1994;331:1286–1292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonsson JR, Clouston AD, Ando Y, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition attenuates the progression of rat hepatic fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:148–155. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.25480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim X, Tateya I, Tateya T, Munoz-Del-Rio A, Bless DM. Immediate inflammatory response and scar formation in wounded vocal folds. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115:921–929. doi: 10.1177/000348940611501212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branski RC, Barbieri SS, Weksler BB, et al. Effects of transforming growth factor-beta1 on human vocal fold fibroblasts. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2009;118:218–226. doi: 10.1177/000348940911800310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul BC, Rafii BY, Gandonu S, Bing R, Amin MR, Branski RC. Smad3: An emerging target for vocal fold fibrosis. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:2237–2231. doi: 10.1002/lary.24723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flanders KC. Smad3 as a mediator of the fibrotic response. Int J Exp Pathol. 2004;85:47–64. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2004.00377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burnett JC, Rossi JJ. RNA-Based Therapeutics: Current Progress and Future Prospects. Chemistry & Biology. 2012;19:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branski RC, Barbieri SS, Weksler BB, et al. The effects of Transforming Growth Factor-beta1 on human vocal fold fibroblasts. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, & Laryngology. 2009;118:218–226. doi: 10.1177/000348940911800310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parekh A, Sandulache VC, Lieb AS, Dohar JE, Hebda PA. Differential regulation of fetal fibroblast collagen gel contraction. Wound Rep Reg. 2007;15:390–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parekh A, Sandulache VC, Singh T, et al. Prostaglandin E2 differentially regulates contraction and structural reorganization of anchored collagen gels by human adult and fetal dermal fibroblasts. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:88–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou H, Felsen D, Sandulache VC, Amin MR, Kraus DH, Branski RC. Prostaglandin (PG)E2 exhibits anti-fibrotic activity in vocal fold fibroblasts. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1261–1265. doi: 10.1002/lary.21795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG. Knocking down barriers: advances in siRNA delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:129–138. doi: 10.1038/nrd2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grotendorst GR. Connective tissue growth factor: a mediator of TGF-β action on fibroblast. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997;8:171–179. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(97)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ylitalo R, Thibeault SL. Relationship between time of exposure of laryngopharyngeal reflux and gene expression in laryngeal fibroblasts. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115:775–783. doi: 10.1177/000348940611501011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phanish MK, Wahab NA, Hendry BM, Dockrell ME. TGF-β1-induced connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) expression in human renal proximal tubule epithelial cells requires Ras/MEK/ERK and Smad signaling. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2005;100:156–165. doi: 10.1159/000085445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh T, Sandulache VC, Otteson TD, et al. Subglottic stenosis examined as a fibrotic response to airway injury characterized by altered mucosal fibroblast activity. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:163–170. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandulache VC, Singh T, Li-Korotky HS, et al. Prostaglandin E2 is activated by airway injury and regulates fibroblast cytoskeletal dynamics. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1365–1373. doi: 10.1002/lary.20173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darby I, Skalli O, Gabbiani G. Alpha-smooth muscle actin is transiently expressed by myofibroblasts during experimental wound healing. Lab Invest. 1990;63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandulache VC, Parekh A, Li-Korotsky HS, Dohar JE, Hebda PA. Prostaglandin E2 inhibition of keloid fibroblast migration, contraction, and transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1-induced collagen synthesis. Wound Rep Reg. 2007;15:122–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2006.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]