Abstract

Plant responses to stress occur via abscisic acid (ABA) dependent or independent pathways. Sucrose non-fermenting1-related protein kinase 2 (SnRK2) play a key role in plant stress signal transduction pathways. It is known that some SnRK2 members are positive regulators of ABA signal transduction through interaction with group A type 2C protein phosphatases (PP2Cs). Here, 10 SnRK2s were isolated from wheat. Based on phylogenetic analysis using kinase domains or the C-terminus, the 10 SnRK2s were divided into three subclasses. Expression pattern analysis revealed that all TaSnRK2s were involved in the responses to PEG, NaCl, and cold stress. TaSnRK2s in subclass III were strongly induced by ABA. Subclass II TaSnRK2s responded weakly to ABA, whereas TaSnRK2s in subclass I were not activated by ABA treatment. Motif scanning in the C-terminus indicated that motifs 4 and 5 in the C-terminus were unique to subclass III. We further demonstrate the physical and functional interaction between TaSnRK2s and a typical group A PP2C (TaABI1) using Y2H and BiFC assays. The results showed that TaABI1 interacted physically with subclass III TaSnRK2s, while having no interaction with subclasses I and II TaSnRK2s. Together, these findings indicated that subclass III TaSnRK2s were involved in ABA regulated stress responses, whereas subclasses I and II TaSnRK2s responded to various abiotic stressors in an ABA-independent manner.

Keywords: TaSnRK2s, abiotic stress, ABA signaling, gene expression, protein–protein interaction, Triticum aestivum

Introduction

Abscisic acid (ABA) is an essential plant hormone that is involved in the abiotic stress response. As a stress hormone, ABA acts through regulatory pathways that control gene expression and stomatal closure (Zhu, 2002; Wasilewska et al., 2008; Lee and Luan, 2012). Increasing evidence shows that the PYR/PYL/RCARs-PP2C-SnRK2 pathway is an essential ABA-dependent stress-signaling pathway and plays a crucial role in the abiotic stress response. There are three major components of the PYR/PYL/RCARs-PP2C-SnRK2 pathway: proteins conferring pyrabactin resistance (1/PYR1-like/regulatory proteins) include ABA receptors (PYR/PYL/RCAR), group-A protein phosphatases 2C (PP2C) and sucrose non-fermenting-1 related protein kinase 2 (SnRK2). In the absence of ABA, PP2C inhibits SnRK2 by direct dephosphorylation. In response to environmental stress, ABA accumulates in plant cells. Increasing endogenous ABA can be sensed and bound by the PYR/PYL/RCAR proteins and repress the activity of PP2C that would otherwise inhibit SnRK2; without PP2c activity, SnRK2 proteins become phosphorylated and trigger the expression of ABA-responsive genes in an ABRE-dependent manner (ABA responsive pathway; Ma et al., 2009; Melcher et al., 2009; Nishimura et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009; Sheard and Zheng, 2009). In this context, group A PP2Cs (e.g., ABI1 and ABI2), function as negative regulators of the ABA response, while SnRK2s act as positive regulators in the ABA signaling pathway (Merlot et al., 2001; Saez et al., 2004; Kuhn et al., 2006; Hirayama and Shinozaki, 2007; Rubio et al., 2009; Nishimura et al., 2010).

The SnRK2s are a relatively small plant-specific gene family, encoding serine/threonine kinases. Increasing evidence shows that individual SnRK2 members have acquired distinct regulatory properties in the abiotic stress response, including ABA responsiveness. In general, SnRK2s in subclass III are strongly activated by ABA, while subclass II members are weakly induced by ABA. Subclass I induction by ABA are moderate (Kobayashi et al., 2004, 2005; Boudsocq et al., 2007; Huai et al., 2008; Fujita et al., 2009). In Arabidopsis, 10 group A PP2Cs interact with SnRK2b members were tested by the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay and consistent with previous studies, SnRK2 subclass III members interacted strongly with group A PP2Cs in various combinations, while subclass II members showed limited interaction with group A PP2Cs (Umezawa et al., 2009). Increasing evidence shows that ABI, a typical member of group A PP2Cs, interacts with subclass III SnRK2s in ABA in the signal transduction pathway (Yoshida et al., 2006; Fujita et al., 2009; Umezawa et al., 2009). Until now, there has been no specific evidence demonstrating whether PP2C interacts with individual SnRK2 members directly.

In wheat, additional SnRK2 members have been reported. The first member of the wheat SnRK2 family, PKABA1, was cloned from an ABA-treated wheat embryo cDNA library (Anderberg and Walker-Simmons, 1992). Thereafter, four PKABA1-like protein kinase genes (TaPK3, W55a, W55b, W55c, and TaSRK2C1) were identified from wheat. The results revealed that all the genes were activated by multiple stressors or ABA application (Holappa and Walker-Simmons, 1997; Xu et al., 2009; Du et al., 2013). In our recent study, four wheat SnRK2 genes (TaSnRK2.3, TaSnRK2.4, TaSnRK2.7, TaSnRK2.8) were cloned. All four genes responded to multiple stressors, though through different mechanisms including ABA responsiveness. Among them, TaSnRK2.3 and TaSnRK2.8 were upregulated by ABA treatment, whereas TaSnRK2.3 and TaSnRK2.7 were not regulated by ABA (Mao et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010, 2011; Tian et al., 2013). Other wheat SnRK2 members have been identified through searches of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) databases, although their specific functions have not been characterized. To date, little is known about the function of wheat SnRK2 members in ABA signaling that activates gene expression in response to abiotic stress.

In this study, we isolated 10 SnRK2 members from wheat and characterized their expression patterns under abiotic stress and ABA treatments. To better understand the function of wheat SnRK2 kinases in ABA signaling, we analyzed the promoter sequences and conserved motifs of SnRK2s, and further demonstrated the biochemical relationship between PP2C and SnRK2 using co-immunoprecipitation, Y2H and bimolecular fluorescence complementation BiFC assays.

Materials and Methods

Cloning of Wheat SnRK2 Members and Sequence Analysis

Based on the sequence data of SAPK5 (AB125306), SAPK6 (AB125307), SAPK9 (AB125310), and SAPK10 (AB125311), the putative full-length cDNAs of TaSnRK2.5, TaSnRK2.6, TaSnRK2.9, and TaSnRK2.10 were inferred by in silico cloning. To obtain the full-length cDNAs, primers were designed from sequences flanking the ORF of the putative sequence (Supplementary Table S1). The full-length cDNAs of TaSnRK2.3, TaSnRK2.4, TaSnRK2.7, and TaSnRK2.8 were obtained from our previous researches (Mao et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010, 2011; Tian et al., 2013). Sequences data of TaSnRK2.1 (TC368696), TaSnRK2.2 (KF688097), and TaSnRK2.10 (KJ0187223) were obtained from NCBI databases.

C-terminal conserved motifs of TaSnRK2s were determined using software tools available at MEME1.

To determine the relationships between TaSnRK2s and SnRK2 homologs in other plant species, CLUSTAL W (1.82) and PHYLIP software (version 3.69) were used to construct a phylogenetic tree, which was viewed using TREEVIEW software.

Promoter Analysis

To isolate the promoter of TaSnRK2s, genomic sequences were used as queries to screen the wheat genome sequencing database using the newly developed rapid ENA sequence similarity search service2 and a genome sequence database of A. tauschii (DD; unpublished data), the diploid D genome donor species of common wheat. A significant match was declared when the queried sequences showed at least 95% nucleotide identity with an expectation value e = 0. The 2-kb region upstream of the translation start site of each gene was considered to be the putative promoter region. The abiotic stress-associated regulatory elements were predicted using the database of plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements at the National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences3.

Plant Treatment

Germinated seeds of hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L., cv. “Hanxuan 10”) were cultured in a growth chamber (20°C, 12 h:12 h photoperiod). Seedlings at the two-leaf stage (9-days-old) were separately stressed by exposure to salt (250 mM NaCl solution); osmotic shock simulating water stress (PEG-6000 (-0.5 MPa) solution); low temperature (4°C) or direct application of ABA (50 μM ABA spray, which was shown to constitute a significant stress in pilot experiments). Untreated control seedlings were cultured normally. Wheat leaves were sampled at 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h after treatments. RNA from each time point was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). To remove traces of genomic DNA contamination, RNA samples were treated with DNase (Invitrogen).

Expression Patterns of TaSnRK2s

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to estimate TaSnRK2s transcript levels resulting from abiotic stresses and ABA application. qRT-PCR was performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Shiga, Japan) using an ABI PRISM 7000 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Specific primers were designed based on cDNA sequences (Supplementary Table S2). Expression of the wheat tubulin gene was used as an internal control for expression levels. The relative expression level of TaSnRK2s was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method (Livaka and Schmittgen, 2001).

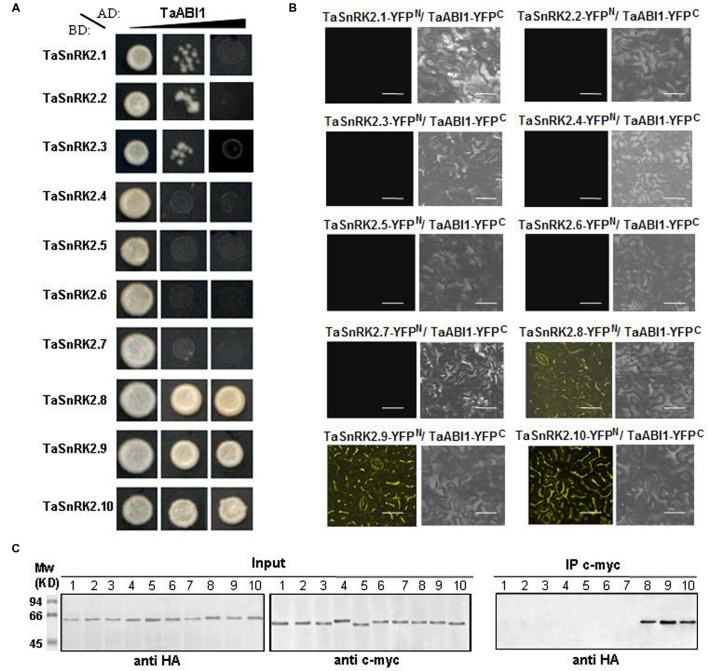

Yeast Two-Hybrid Analysis

Yeast two-hybrid analysis was performed using the MatchMaker GAL4 two-hybrid system-3 (Clontech, USA) according to kit instructions. Yeast strain (AH109) was transformed with pGBKT7 vectors harboring the coding region of each TaSnRK2 insert and a pGADT7 vector harboring the coding region of TaABI1. The transformants were grown on auxotrophic media as indicated in Figure 4A. Primers used for cloning are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

FIGURE 4.

Physical interactions among TaABI1 and TaSnRK2s. (A) Yeast two-hybrid analysis of GAL4AD:TaABI1 and GAL4BD:TaSnRK2s were transformed to yeast cells as indicated. Black slopes indicate screening stringency of SD media supplemented with: left, -LW; center, -LWH + 10 mM 3-AT; right, -LWHA + 30 mM 3-AT. (B) BiFC image of TaABI1 and TaSnRK2s. BiFC analyses were performed in epidermal cells of tobacco leaves. Left, YFP fluorescence image; right, bright field. Bars = 50 μm. (C) The results of the BiFC experiments were confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation. The expression of the YFPN and YFPC fusion proteins in tobacco leaves was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-c-myc and anti-HA antibodies. Proteins immunoprecipitated by the anti-c-myc antibody were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibodies. Number 1–10 indicated TaSnRK2.n-YFPN/TaABI1-YFPC.

Transient Expression Assay

The vectors pUC-SPYNE (yellow fluorescent protein [YFP] N-terminal fragment, YN) and, pUC-SPYCE (YFP C-terminal Fragment, YC), used in the bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay, were obtained from Harter and Kudla (Walter et al., 2004). The coding sequences of TaSnRK2s were cloned into pUC-SPYCE to create fusion constructs with the N-terminal fragment of yellow fluorescent protein (YN). The coding sequence of TaABI1 was cloned into pUC-SPYNE to create a fusion with the C-terminal fragment of YFP (YC). The cloning primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The recombinant constructs were co-transfected into A. tumefaciens (strain GV3101), and then transferred into tobacco leaves by infiltration using a 1-mL syringe. For microscopic analyses, leaf disks were removed 4 days after infiltration. Cells of the lower epidermis were examined for YFP fluorescence with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leika TCS-NT). Negative controls consisted of pUC-SPYNE co-transfected with pUC-SPYCE, or either blank vector paired with one of the treatment vectors.

Protein assays, immunoprecipitation and western blotting were performed as described previously (Umezawa et al., 2009). For immunoprecipitation experiments, transfected tobacco leaves were extracted in PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). HA-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated and purified using superparamagnetic micro MACS beads coupled to monoclonal anti HA antibody according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma). Purified immunocomplexes were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-myc antibody (Roche).

Results

Molecular Characterization of TaSnRK2s

Ten SnRK2 genes were identified from wheat (Table 1), which were designated TaSnRK2.1 to TaSnRK2.10. Scansite analysis indicated that TaSnRK2s have potential serine/threonine protein kinases activities, and like other SnRK2s, contain an N-terminal catalytic domain and a C-terminal regulatory region. The N-terminal catalytic domain is highly conserved, containing an ATP binding site and protein kinase activating signature. The C-terminal regions of TaSnRK2s are quite divergent and contain regions rich in acidic amino acids.

Table 1.

Summary information for TaSnRK2 genes.

| Name | ORF (bp) | Length (aa) | Mol. wt. (kd) | pI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaSnRK2.1 | 1029 | 343 | 38.85 | 5.83 |

| TaSnRK2.2 | 1026 | 342 | 38.64 | 5.51 |

| TaSnRK2.3 | 1029 | 343 | 38.48 | 5.69 |

| TaSnRK2.4 | 1092 | 364 | 42.15 | 6.05 |

| TaSnRK2.5 | 969 | 323 | 37.02 | 10.35 |

| TaSnRK2.6 | 1074 | 358 | 40.90 | 5.60 |

| TaSnRK2.7 | 1074 | 358 | 40.91 | 5.61 |

| TaSnRK2.8 | 1101 | 367 | 41.59 | 4.77 |

| TaSnRK2.9 | 1047 | 349 | 38.94 | 5.03 |

| TaSnRK2.10 | 1053 | 351 | 39.58 | 4.68 |

Accession numbers of TaSnRK2.1, TaSnRK2.2, and TaSnRK2.10 are TC368696, KF688097, and KJ0187223. The cDNAs of TaSnRK2.3, TaSnRK2.4, TaSnRK2.7, and TaSnRK2.8 were obtained in our previous research (Mao et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010, 2011; Tian et al., 2013). Others are from the experiments of the present study.

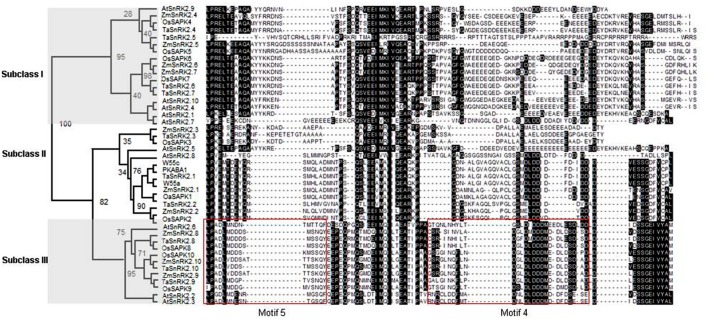

Phylogenetic Analysis of TaSnRK2s Proteins

A phylogenetic tree was constructed with the amino acid sequences of the C-terminus of SnRK2 family proteins, including those from wheat, rice, maize, and Arabidopsis. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that these protein kinases were divided into three subclasses, namely subclasses I, II, and III, which contained TaSnRK2.4 through TaSnRK2.7 (Class I), TaSnRK2.1 through TaSnRK2.3 (Class II), and TaSnRK2.8 through TaSnRK2.10 (class III), respectively (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic tree and sequence alignment of the C-terminus of SnRK2 family. Sequences showed in the boxes are motifs 4 and 5 of subclass III TaSnRK2s. The phylogenetic tree was constructed putative amino acid sequences using the PHYLIP 3.68 package. Bootstrap values are in percentages. Os, O. sativa; At, A. thaliana; Zm, Z. mays; Ta, T. aestivum.

Based on functional and sequence divergence, SnRK2s are divided into three distinct subclasses, namely SnRK2a (corresponding to subclass I) and SnRK2b (corresponding to subclasses II and III; Halford and Hardie, 1998). Similar to previous reports, a comparison of C-terminal sequences suggested that there were more structural similarities between subclasses II and III than other pairs (Figure 1). For example, the C-terminal blocks in subclasses II and III are conserved; there are fewer amino acids in subclasses II and III than in subclass I; and the acidic patches of subclass I are abundant in Glu, while those of subclasses II and III are rich in Asp.

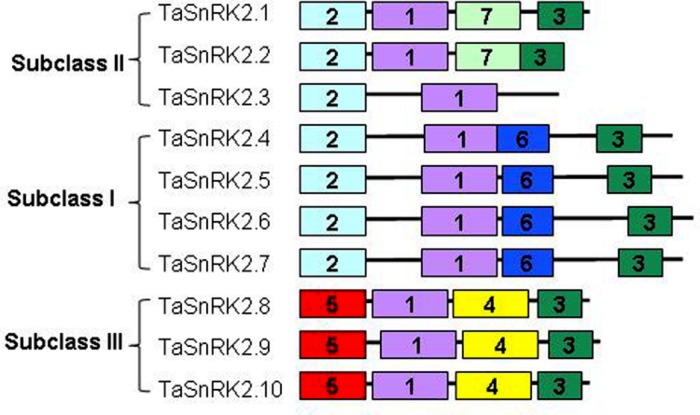

Conserved Motifs in the C-terminus of TaSnRK2 Kinases

Increasing evidence has shown that there are seven functional domains in the C-terminal regions of SnRK2s although they are divergent (Yoshida et al., 2006; Yuasa et al., 2007; Huai et al., 2008). As shown in Figure 2, motif 1 existed in all TaSnRK2 members. Motif 3 was found in all SnRK2 members except TaSnRK2.3. Motif 2 is unique to subclasses II and III TaSnRK2s. Motifs 4 and 5 are unique to subclass III TaSnRK2s, and motif 6 was only identified in subclass I TaSnRK2s. Motif 7 is unique to TaSnRK2.1 and TaSnRK2.2.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of the seven conserved motifs in the C-terminus of TaSnRK2s. Each motif is represented by a different colored box. Black lines represent the non-conserved sequences.

Regulatory Elements in the Promoters of TaSnRK2s

As shown in Table 2, 15 cis-acting elements related to stress responses in the promoter regions of the TaSnRK2s were identified, including ABA response elements (ABRE), low temperature response elements (LTREs), dehydration-response elements (ACGTATERD1 and DRE), and binding sites for MYB/MYC transcription factors. Nine MYB/MYC binding sites, which are related to biotic and abotic stress resistance (Du et al., 2012; Hou et al., 2012), were found in the promoters of TaSnRK2s. TaSnRK2 members (1–10) had 27, 29, 28, 45, 47, 42, 40, 39, 29, and 26 copies of these elements, respectively. MYB/MYC binding sites were most common in subclass I TaSnRK2s. In addition, the numbers of ABRE elements existing in TaSnRK2s promoters (1–10) were 14, 2, 15, 1, 2, 13, 11, 2, 4, and 7. The subclass I TaSnRK2s (TaSnRK2.4-7), which were not activated by ABA, contain several ABREs in their promoter regions.

Table 2.

Stress-related cis elements identified in the 2-kb upstream region of TaSnRK2s.

| Cis-elemnent | Sequence | Code | TaSnRK2 member | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| ABRELATERD1 | ACGTG | S000414 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| ABRERATCAL | MACGYGB | S000507 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| ACGTATERD1 | ACGT | S000415 | 12 | 8 | 18 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 8 | 10 |

| DRECRTCOREAT | RCCGAC | S000418 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| LTRECOREATCOR15 | CCGAC | S000153 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| LTRE1HVBLT49 | CCGAAA | S000250 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| MYB1AT | WAACCA | S000408 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| MYBATRD22 | CTAACCA | S000175 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MYBCORE | CNGTTR | S000176 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| MYB2CONSENSUSAT | YAACKG | S000409 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| MYCCONSENSUSAT | CANNTG | S000407 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 34 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 18 | 16 |

| MYBCOREATCYCB1 | AACGG | S000502 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| MYBGAHV | TAACAAA | S000181 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| MYBPZM | CCWACC | S000179 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| MYBST1 | GGATA | S000180 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

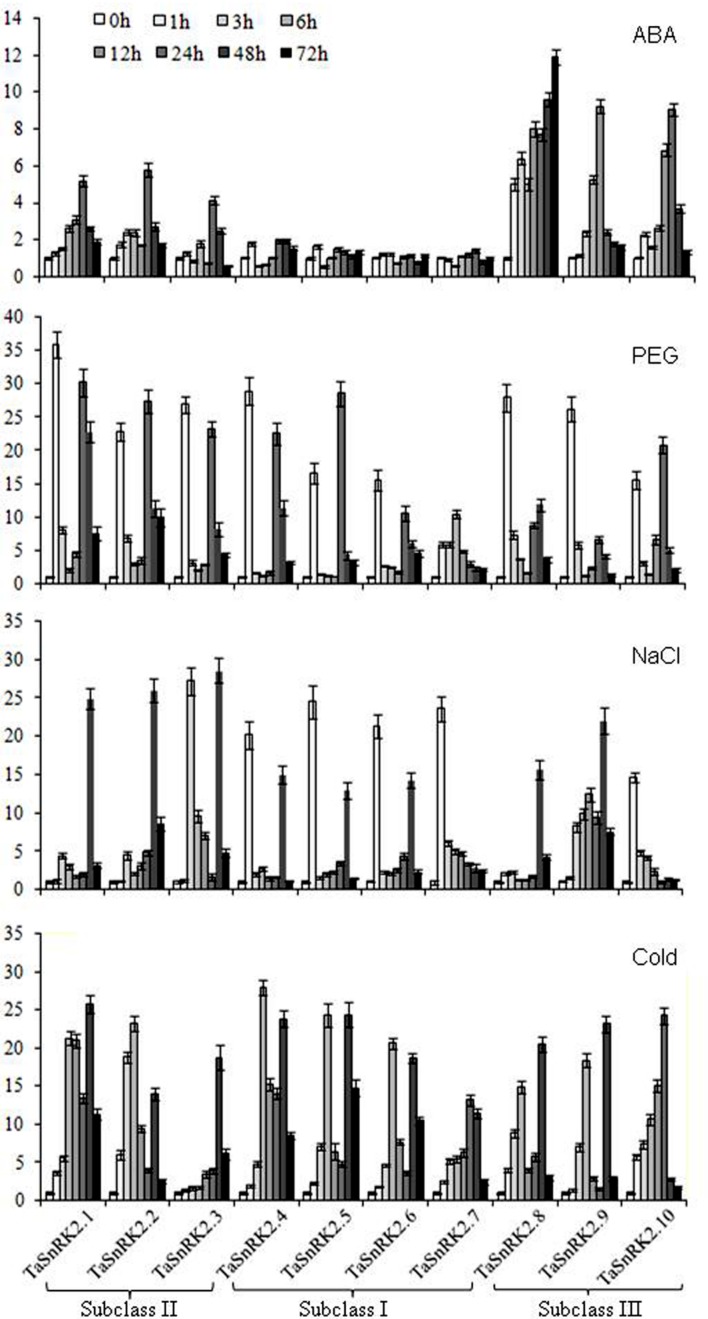

Expression Patterns of SnRK2 Members of Wheat as a Function of Stressor

The expression of the 10 TaSnRK2s was detected by qRT-PCR (Figure 3). Different expression patterns of different members were observed under ABA, water deficit, salt and low temperature stress. In general, ABA treatment showed the weakest stress response among the four treatments. The transcripts of TaSnRK2s in subclass III were induced strongly, TaSnRK2s in subclass II induced weakly, whereas TaSnRK2s in subclass I were not activated by ABA treatment.

FIGURE 3.

Expression patterns of TaSnRK2s in response to ABA, PEG, NaCl, and cold treatments. Tubulin was used as an internal control. The expression of TaSnRK2s at 0 h was regarded as the standard. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3).

Water deficit, simulated by PEG treatment, was the most powerful stimulant for TaSnRK2 genes. All TaSnRK2 members were induced quickly by PEG treatment, responding within 1 h or less, much more rapidly than other stressors. The expression patterns of all TaSnRK2s members (except TaSnRK2.7) under PEG treatment had unique expression profiles, responding with a bimodal pattern showing high expression at 3 and 24 h, but decreased expression at 3, 6, and 12 h after treatment. For most of the constructs, expression increased again at 24–48 h but decreased by 72 h.

All the TaSnRK2s were activated by NaCl and cold treatment. Among them, TaSnRK2.10 and TaSnRK2s in subclass I responded to salt stress within 1 h. The transcriptional maxima of other TaSnRK2s were variable; constructs in subclass II as well as TaSnRK2.8 and 9, showed high levels of transcription at 48 h under salt stress. Low temperature also resulted in higher levels of TaSnRK2 transcription. Transcription generally increased over the time course, with maximal levels occurring at 6 h or later.

Physical Interaction between SnRK2 and PP2C

A typical group A PP2Cs, TaABI1, was cloned in a previous study (Nakamura et al., 2007). To better understand the biochemical relation between PP2C and each TaSnRK2 member in ABA signaling, we tested their interaction by Y2H, BiFC assay, and co-immunoprecipitation (Figures 4A–C, respectively). As shown in Figure 4A, TaABI1 strongly interacted with TaSnRK2 subclass III members, while showing limited or no interaction with subclasses I and II members. To confirm these interactions in vivo, the two classes of proteins were co-expressed in tobacco cells using the BiFC assay. In the BiFC assay, interacting partners bring the N-terminal and C-terminal components of YFP together, resulting in YFP fluorescence. Each TaSnRK2 N-term fusion was co-transfected with the C-term TaABI1 fusion construct. Confirming our Y2H results, the C-term-TaABI1 construct complemented subclass III N-term constructs to give strong YFP fluorescence in tobacco cells (Figure 4B). We further confirmed this result with co-immunoprecipitation of TaABI1:c-myc fusions with subclass III TaSnRK2s:HA fusions (Figure 4C). Together, these results indicate that TaABI1 interacted strongly with subclass III TaSnRK2s, whereas there was no evidence for interaction with subclasses I and II TaSnRK2s.

Discussion

Plant stress resistance is achieved by complex networks of signal transduction via both ABA-dependent and ABA-independent resistance mechanisms. It was reported that the SnRK2 family of Arabidopsis, rice and maize have evolved specifically to respond to various types of stress and that individual members have acquired distinct regulatory properties, including ABA responsiveness (Kobayashi et al., 2004; Boudsocq et al., 2007; Huai et al., 2008). Here, 10 SnRK2 members in wheat were cloned and characterized. Gene structure and phylogenetic analysis showed similarity between SnRK2 members of wheat to counterparts in Arabidopsis, maize and rice, implying the SnRK2 kinase evolved before the divergence of dicots and monocots.

TaSnRK2s contain two typical domains, the conserved N-terminal catalytic domain and the somewhat variable C-terminal domain. Compelling evidence showed that the C-terminal domain plays a role in the activation of the kinase by participation in protein–protein interactions, mainly involved in ABA responsiveness and signal transduction (Kobayashi et al., 2005; Riichiro et al., 2006; Florina et al., 2009). Conserved motif analysis indicated that seven motifs were unevenly distributed in the C-terminus of TaSnRK2s. Among them, motifs 1 and 3 existed almost all the members, motif 2 was present in subclasses II and III, motif 6 was unique to subclass I, and motifs 4 and 5 were unique to subclass III. This is in agreement with findings in the maize SnRK2 family, suggesting that: (1) motifs 1 and 3 formed before the differentiation of three classes and were essential for the regulatory function of the C-terminus; (2) gene members classified in same group have same motifs, perhaps reflecting similar functions; (3) motifs 4 and 5 might participate in the ABA response according to the specific class (Huai et al., 2008). Further studies are required on the motif-exchange experiment using protein interaction assay.

Transcription patterns can indicate a gene’s involvement in functional or differential events. Numerous studies have demonstrated that SnRK2 is involved in multiple abiotic stress responses. In this study, the expression of TaSnRK2s was induced by water deficit, salt and cold, and individual members have acquired distinct regulatory properties. The transcripts of subclass III TaSnRK2s were strongly induced by ABA, subclass II TaSnRK2s responded to ABA weakly and TaSnRK2s in subclass I were not activated by ABA treatment. These results suggest that TaSnRK2s are involved in various abiotic stress responses via different mechanisms. Most TaSnRK2s were highly sensitive to osmotic stress because this stressor strongly induced transcription within an hour of exposure and generally caused the highest levels of transcription compared to the other stressors. Evidence from cultured plant cells support these findings, showing extremely early activation of NtOSAK and AtSRK2C, implied that SnRK2s may be induced immediately by osmotic stress (Kelner et al., 2004; Umezawa et al., 2004).

Analyzing the cis elements in the promoters of TaSnRK2s showed that their promoters are differentially regulated and carry a large number of stress-related cis elements. However, it was found that genes induced by a particular stressor do not all have corresponding cis elements in their promoters. For instance, only two ABREs were present in TaSnRK2.8 promoter, although it was strongly induced by ABA. There were 13 ABREs in TaSnRK2.6, while it was not activated by ABA. These findings indicate that there are likely other unrecognized stress-related cis elements and/or unknown mechanisms involved in the regulation of these genes.

Increasing evidence show that SnRK2 genes play important roles in abiotic stress responses in plants via ABA dependent or independent signaling pathways. The subclass III SnRK2 kinases are the center of the ABA signaling network through interaction between SnRK2 and PP2C (Yoshida et al., 2006; Fujita et al., 2009; Umezawa et al., 2009). These findings were supported by the Y2H and BiFC assays reported in this study. Furthermore, subclasses I and II TaSnRK2s failed to interact with group A PP2Cs. However, subclass II TaSnRK2s were weakly activated by ABA in the expression pattern analysis. These results suggested that (1) subclass I TaSnRK2s respond to various abiotic stresses in an ABA-independent manner; (2) subclass II TaSnRK2s might participate in ABA independent signaling involved in cross-communication between ABA-dependent and ABA-independent signaling networks. Further studies are required on the relationship between SnRK2 kinases and the ABA independent signal transduction pathway; in addition, a better understanding of the biochemical relationships between PP2C and SnRK2 will elucidate the molecular mechanisms of SnRK2 and adaptive cellular mechanisms in stressed plants.

This study primarily concerned the characterization of wheat SnRK2 genes involved in abiotic-stressed responses. Further comprehensive investigations to demonstrate the biochemical relation between PP2C and each SnRK2 were studied. The results of these studies enable us to dissect the actual molecular mechanisms of each SnRK2s in abiotic stress response.

Author Contributions

HZ and WL performed the experiments and participated to the data analysis. XM performed the qRT-PCR experiments, RJ projected design and supervision. HJ analyzed the data and revised the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF31401371) and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation of (BJNSF6132030).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.00420

References

- Anderberg R. J., Walker-Simmons M. K. (1992). Isolation of a wheat cDNA clone for an abscisic acid-inducible transcript with homology to protein kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89 10183–10187. 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudsocq M., Droillard M. J., Barbier-Brygoo H., Lauriere C. (2007). Different phosphorylation mechanisms are involved in the activation of sucrose non-fermenting 1 related protein kinases 2 by osmotic stresses and abscisic acid. Plant Mol. Biol. 63 491–503. 10.1007/s11103-006-9103-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H., Yang S. S., Liang Z., Feng B. R., Liu L., Huang Y. B., et al. (2012). Genome-wide analysis of the MYB transcription factor superfamily in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 12:106 10.1186/1471-2229-12-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X. M., Zhao X. L., Li X. J., Guo C. J., Lu W. J., Gu J. T., et al. (2013). Overexpression of TaSRK2C1, a wheat SNF1-related protein kinase 2 gene, increases tolerance to dehydration, salt, and low temperature in transgenic tobacco. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 31 810–821. 10.1007/s11105-012-0548-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Florina V., Silvia R., Americo R., Caroline S., Christophe B., Nadia R., et al. (2009). Protein phosphatases 2C regulate the activation of the Snf1-related kinase OST1 by abscisic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21 3170–3184. 10.1105/tpc.109.069179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y., Nakashima K., Yoshida T., Katagiri T., Kidokoro S., Kanamori N., et al. (2009). Three SnRK2 protein kinases are the main positive regulators of abscisic acid signaling in response to water stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 50 2123–2132. 10.1093/pcp/pcp147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford N. G., Hardie D. G. (1998). SNF1-related protein kinases: global regulators of carbon metabolism in plants? Plant Mol. Biol. 37 735–748. 10.1023/A:1006024231305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama T., Shinozaki K. (2007). Perception and transduction of abscisic acid signals: keys to the function of the versatile plant hormone ABA. Trends Plant Sci. 12 343–351. 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holappa L. D., Walker-Simmons M. K. (1997). The wheat protein kinase gene, TaPK3, of the PKABA1 subfamily is differentially regulated in greening wheat seedlings. Plant Mol. Biol. 33 935–941. 10.1023/A:1005720203535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L., Chen L., Wang J., Xu D., Dai L., Zhang H., et al. (2012). Construction of stress responsive synthetic promoters and analysis of their activity in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 30 1496–1506. 10.1007/s11105-012-0464-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huai J., Wang M., He J., Zheng J., Dong Z., Lv H., et al. (2008). Cloning and characterization of the SnRK2 gene family from Zea mays. Plant Cell Rep. 27 1861–1868. 10.1007/s00299-008-0608-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelner A., Pekala L., Kaczanowski S., Muszynska G., Hardie D. G., Dobrowolska G. (2004). Biochemical characterization of the tobacco 42-KD protein kinase activated by osmotic stress. Plant Physiol. 136 3255–3265. 10.1104/pp.104.046151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y., Murata M., Minami H., Yamamoto S., Kagaya Y., Hobo T., et al. (2005). Abscisic acid-activated SNRK2 protein kinases function in the gene-regulation pathway of ABA signal transduction by phosphorylating ABA response element-binding factors. Plant J. 44 939–949. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02583.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y., Yamamoto S., Minami H., Kagaya Y., Hattori T. (2004). Differential activation of the rice sucrose nonfermenting1-related protein kinase2 family by hyperosmotic stress and abscisic acid. Plant Cell 16 1163–1177. 10.1105/tpc.019943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn J. M., Boisson-dernier A., Dizon M. B., Maktabi M. H., Schroeder J. I. (2006). The protein phosphatase AtPP2CA negatively regulates abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis, and effects of abh1 on AtPP2CA mRNA. Plant Physiol. 140 127–139. 10.1104/pp.105.070318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. C., Luan S. (2012). ABA signal transduction at the crossroad of biotic and abiotic stress responses. Plant Cell Environ. 35 53–60. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02426.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livaka K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Szostkiewicz I., Korte A., Moes D., Yang Y., Christmann A., et al. (2009). Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 324 1064–1068. 10.1126/science.1172408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X. G., Zhang H. Y., Tian S. J., Chang X. P., Jing R. L. (2009). TaSnRK2.4, an SNF1-type serine/threonine protein kinase of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), confers enhanced multistress tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 61 683–696. 10.1093/jxb/erp331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher K., Ng L. M., Zhou X. E., Soon F. F., Xu Y., Suino-Powell K. M., et al. (2009). A gate-latch-lock mechanism for hormone signaling by abscisic acid receptors. Nature 462 602–608. 10.1038/nature08613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlot S., Gosti F., Guerrier D., Vavasseur A., Giraudat J. (2001). The ABI1 and ABI2 protein phosphatases 2C act in a negative feedback regulatory loop of the abscisic acid signalling pathway. Plant J. 25 295–303. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00965.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S., Komatsuda T., Miura H. (2007). Mapping diploid wheat homologues of Arabidopsis seed ABA signaling genes and QTLs for seed dormancy. Theor. Appl. Genet. 114 1129–1139. 10.1007/s00122-007-0502-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura N., Hitomi K., Arvai A. S., Rambo R. P., Hitomi C., Cutler S. R., et al. (2009). Structural mechanism of abscisic acid binding and signaling by dimeric PYR1. Science 326 1373–1379. 10.1126/science.1181829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura N., Sarkeshik A., Nito K., Park S. Y., Wang A., Carvalho P. C., et al. (2010). PYR/PYL/RCAR family members are major in-vivo ABI1 protein phosphatase 2C-interacting proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 61 290–299. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04054.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. Y., Fung P., Nishimura N., Jensen D. R., Fujii H., Zhao Y., et al. (2009). Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science 324 1068–1071. 10.1126/science.1173041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riichiro Y., Taishi U., Tsuyoshi M., Seiji T., Fuminori T., Kazuo S. (2006). The regulatory domain of SRK2E/OST1/SnRK2.6 interacts with ABI1 and integrates abscisic acid (ABA) and osmotic stress signals controlling stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 281 5310–5318. 10.1074/jbc.M509820200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio S., Rodrigues A., Saez A., Dizon M. B., Galle A., Kim T. H., et al. (2009). Triple loss of function of protein phosphatases type 2C leads to partial constitutive response to endogenous abscisic acid. Plant Physiol. 150 1345–1355. 10.1104/pp.109.137174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez A., Apostolova N., Gonzalez-Guzman M., Gonzalez-Garcia M. P., Nicolas C., Lorenzo O., et al. (2004). Gain-of-function and loss-of-function phenotypes of the protein phosphatase 2C HAB1 reveal its role as a negative regulator of abscisic acid signalling. Plant J. 37 354–369. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01966.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheard L. B., Zheng N. (2009). Plant biology: signal advance for abscisic acid. Nature 462 575–576. 10.1038/462575a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian S. J., Mao X. G., Zhang H. Y., Chen S. S., Zhai C. C., Yang S. M., et al. (2013). Cloning and characterization of TaSnRK2.3, a novel SnRK2 gene in common wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 64 2063–2080. 10.1093/jxb/ert072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa T., Sugiyama N., Mizoguchi M., Hayashi S., Myouga F., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., et al. (2009). Type 2C protein phosphatases directly regulate abscisic acid-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 17588–17593. 10.1073/pnas.0907095106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa T., Yoshida R., Maruyama K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (2004). SRK2C, a SNF1-related protein kinase 2, improves drought tolerance by controlling stress-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 17306–17311. 10.1073/pnas.0407758101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter M., Chaban C., Schutze K., Batistic O., Weckermann K., Nake C., et al. (2004). Visualization of protein interactions in living plant cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Plant J. 40 428–438. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02219.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasilewska A., Vlad F., Sirichandra C., Redko Y., Jammes F., Valon C., et al. (2008). An update on abscisic acid signaling in plants and more. Mol. Plant 2 198–217. 10.1093/mp/ssm022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. S., Liu L., Ni Z. Y., Liu P., Chen M., Li L. C., et al. (2009). W55a encodes a novel protein kinase that Is involved in multiple stress responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 51 58–66. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00776.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida R., Umezawa T., Mizoguchi T., Takahashi S., Takahashi F., Shinozaki K. (2006). The regulatory domain of SRK2E/OST1/SnRK2.6 interacts with ABI1 and integrates abscisic acid (ABA) and osmotic stress signals controlling stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 281 5310–5318. 10.1074/jbc.M509820200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa T., Tomikubo Y., Yamauchi T., Inoue A., Iwaya-Inoue M. (2007). Environmental stresses activate a tomato SNF1-related protein kinase 2 homolog, SlSnRK2C. Plant Biotechnol. 24 401–408. 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.24.401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. Y., Mao X. G., Jing R. L., Xie H. M. (2011). Characterization of common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) TaSnRK2.7 gene involved in abiotic stress responses. J. Exp. Bot. 62 975–988. 10.1093/jxb/erq328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. Y., Mao X. G., Wang C. S., Jing R. L. (2010). Overexpression of a common wheat gene TaSnRK2.8 enhances tolerance to drought, salt and low temperature in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 5:e16041 10.1371/journal.pone.0016041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. K. (2002). Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53 247–273. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.