Abstract

Background

Non-invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) with high-grade dysplasia and IPMN-associated invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) are frequently included under the term “malignancy”. The goal of this study is to clarify the difference between these two entities.

Methods

From 1996 to 2013, data of 616 patients who underwent pancreatic resection for an IPMN were reviewed.

Results

The median overall survival for patients with IPMN with high-grade dysplasia (92 months) was similar to survival for patients with IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia (118 months, p = 0.081), and superior to that of patients with IPMN-associated PDAC (29 months, p < 0.001). IPMN-associated PDAC had lymph node metastasis in 53%, perineural invasion in 58%, and vascular invasion in 33%. In contrast, no lymph node metastasis, perineural or vascular invasion was observed with high-grade dysplasia. None of the patients with IPMN with high-grade dysplasia developed recurrence outside the remnant pancreas. In stark contrast 58% of patients with IPMN-associated PDAC recurred outside the remnant pancreas. The rate of progression within the remnant pancreas was significant in patients with IPMN with high-grade (24%) and with low/intermediate dysplasia (22%, p = 0.816).

Conclusion

Non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia should not be considered a malignant entity. Compared to patients with IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia, those with high-grade dysplasia have an increased risk of subsequent development of PDAC in the remnant pancreas.

Introduction

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) is a common cystic neoplasm of the pancreas that is characterized by mucin-secreting intraductal papillary proliferations of neoplastic epithelium.1, 2, 3, 4 IPMNs were originally described in 1982 by Ohhashi et al.5 and defining characteristics were outlined by the World Health Organization in 1996.6 Similar to pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), IPMN is a precursor lesion that can progress to invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) through a spectrum of dysplastic changes that range from low to high-grade dysplasia. This progression model for the development of PDAC is thought to be analogous to the adenoma-to-carcinoma progression of colorectal cancer.7 One limitation in interpreting the results of the numerous publications on the pathobiology of IPMN is the imprecision in terminology. In particular, the term “malignancy” is used variably and in some reports includes both IPMN-associated PDAC and non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia, while in other reports malignancy is only used to describe IPMN-associated PDAC. As a result of this discrepancy, there is considerable variability reported for the biological behavior of IPMN as a function of pathological grade. For example, the prevalence of “malignancy” ranges from 6% to 66% in reports of surgically resected IPMNs.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 A large part of this variation can be accounted for by the definition of malignancy employed. As a result, variability is observed in the reported survival rates after resection. The 5-year survival rate is reported to be from 77% to 100% for “non-malignant”, and 22% to 62% for “malignant” IPMNs.8, 14, 15, 21, 22, 23, 24

In 1996, the WHO established guidelines for the precise nomenclature of IPMN.6 IPMN with an associated invasive carcinoma (IPMN-associated PDAC) is defined by an IPMN with a neoplastic component, which has invaded across the basement membrane of the duct. This represents true “malignancy” as these lesions have the clear potential for systemic spread. In contrast, non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia is composed of cells with marked nuclear atypia and complex architecture with an unorganized cellular arrangement similar to invasive carcinoma, but the neoplastic cells have not invaded across the basement membrane. The synonymous term of carcinoma in situ is less often used and has been replaced by the more appropriate term high-grade dysplasia. The neoplastic cells of high-grade dysplasia, which presumably lack potential for systemic spread, are considered to be a precursor lesion.

In order to document better the differences in biological behavior of IPMN-associated PDAC (true malignancy) and IPMN with high-grade dysplasia, the objective of this study was to demonstrate the disease-specific outcomes of patients who underwent resection of these lesions. Specifically, we performed a retrospective analysis of a large single-institutional series of resected patients in which IPMN-associated PDAC and non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia were consistently and precisely defined according to the WHO definitions. We further compared disease-specific local/regional recurrence, systemic recurrence and disease progression in the pancreatic remnant, as well as the disease-specific survival of the patients with IPMN-associated PDAC and non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia.

Methods

Study population

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Hospital institutional review board (IRB). Review of a prospectively maintained database identified 642 consecutive patients who underwent a pancreatectomy for an IPMN from 1996 to 2013 at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Patients with an unknown grade of dysplasia or those with a concomitant invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, coexisting but separate from IPMN, were excluded from the cohort. A total of 616 patients with an IPMN with a clearly defined grade of dysplasia or diagnosis of IPMN with an associated PDAC (IPMN-associated PDAC) formed the population of this study. Clinical information, including patients' age and gender, pre-operative presenting symptoms; and pathologic data, including tumor size (with the size of the non-invasive IPMN and invasive cancer clearly separated), grade of dysplasia, type of invasive pancreatic cancer, lymph node metastasis, perineural and vascular invasion, and resection margin status were obtained.

Pathologic examination of IPMNs

In general, all patients were approached with a targeted partial pancreatectomy to resect the index lesion followed by frozen section analysis of margins. The majority of the patients at Johns Hopkins Hospital undergo surgical resection based on the International Consensus Guidelines resection criteria.25 Patients with a presumably benign IPMN undergo resection when there is a strong family history of pancreatic cancer or when the patient has the willing to proceed to operation.

IPMN was defined as a mucin-producing cystic neoplasm with tall, columnar epithelial cells, with or without papillary projections that extensively involve the main pancreatic duct or its side branches. Lesions were assigned to only one category consisting of low-grade dysplasia, intermediate-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia or IPMN with invasive carcinoma based on the highest grade of dysplasia/carcinoma encountered in the specimen. IPMN-associated PDAC (pancreatic adenocarcinoma arising in association with an IPMN) were further classified onto two subtypes: tubular adenocarcinoma, composed of predominantly gland-forming neoplastic cells with fibrotic stroma and absence of significant extracellular stromal mucin (i.e. conventional PDAC); and colloid carcinoma (mucinous non-cystic carcinoma), composed of sparsely populated strips, clusters, or individual neoplastic cells residing within extensive pools of extracellular mucin (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

a) IPMN with high-grade dysplasia is composed of cells with marked nuclear atypia and complex architecture with an unorganized cellular arrangement similar to invasive carcinoma but in contrast to invasive cancer lacks invasion of the basement membrane. b) Colloid carcinoma (mucinous non-cystic carcinoma), composed of sparsely populated strips, clusters, or individual neoplastic cells residing within extensive pools of extracellular mucin. These neoplastic cells commonly contain intracytoplasmic mucin. c) IPMN-associated tubular adenocarcinoma composed of predominantly gland-forming neoplastic cells with fibrotic stroma and absence of significant extracellular mucin

When appropriate the nodal status and presence of perineural and vascular invasion were also recorded. The tumor size was evaluated based on the maximal size measured on pathologic examination. The size of only the invasive component in tumors was considered the size of the invasive carcinoma. The resection margins that were routinely assessed included pancreatic neck, uncinate (superior mesenteric artery), bile duct/hepatic duct margin, and enteric resection lines. Margin involvement was defined as presence of IPMN with any grade of dysplasia or invasive adenocarcinoma at the resection line. A positive margin was further classified based on the highest grade of dysplasia identified at the margin or, in the case of invasive cancer, as R0 (negative margin), R1 (microscopic positive margin) or R2 (macroscopic tumor left at the margin).

Evaluation of recurrence and survival outcomes

Post-operative follow-up data were collected from information obtained during routine surveillance clinic visits. In general, patients were followed for recurrence or progression every 3–6 months if they have IPMN-associated PDAC and 6–12 months if they have non-invasive IPMN with imaging studies that included at least one of the following: computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). For patients with non-invasive IPMN, progression in the remnant pancreas was defined as radiologic evidence of a new IPMN, a new solid component within an existing IPMN in the remnant pancreas, a significant increase in the size of the main pancreatic duct in the remnant pancreas, development of a metachronous PDAC in the remnant pancreas or a clinically significant increase in size of an existing cyst in the remnant pancreas. In addition, the presence of a new PDAC in the remnant pancreas with metastatic disease was also counted as progression. In patients with an initial resection of an IPMN-associated PDAC, recurrence was determined by cross-sectional imaging and defined by the typical patterns of recurrence for resected PDAC. That is, local/regional recurrence was defined by the development of soft tissue in the tumor resection bed and systemic recurrence was determined by evidence of liver, lung or peritoneal metastases. In all cases, recurrence or progression was evaluated only among patients who had more than 6 month of follow-up. The time to disease progression was calculated from the time of original diagnoses at pathologic assessment of surgically removed specimens to the time of the progression diagnosed on follow-up imaging evaluations. Survival time was calculated from the time of surgical resection to death, whereas follow-up time was based on time of surgery to the most recent clinic visit. The survival analysis in the study is disease-specific–thus patients who died of causes other than pancreatic cancer were censored along with those who were still alive at last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

For the purpose of performing a comparative analysis, patients were stratified into 3 groups based on degree of dysplasia as follows: low/intermediate-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and IPMN-associated PDAC. In some analyses, IPMN-associated tubular carcinoma and colloid carcinoma were separated as indicated in the results. The clinical and pathologic characteristics of these groups were compared using statistical methods as follows. Continuous variables were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) and were compared using a Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test. To compare the categorical variables, a chi-squared test or a fisher-exact test were performed. Kaplan–Meier survival estimates and a log-rank test were used to estimate the survival in IPMNs with different grades of dysplasia. To evaluate the independent factors associated with survival we used a cox-proportional hazard regression. Possible factors related to development of PDAC in patients underwent resection for low/intermediate-grade dysplasia or high-grade dysplasia were evaluated using univariate and multivariate regression models. A backward step-wise elimination with a threshold of p = 0.20 was used to select the variables for the final multivariate model. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics

From 1996 to 2013, a total of 616 patients who met inclusion criteria underwent resection for an IPMN. The median age of the cohort was 70 years (IQR, 62–76), and 315 (51%) of the 616 patients were male. A total of 368 (60%) patients were symptomatic. The presenting symptoms included weight loss in 155 (25%), abdominal pain in 266 (43%) and jaundice in 89 (15%) patients. A pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed in 405 (66%) patients; a distal pancreatectomy in 141 (23%), a total pancreatectomy in 61 (10%) and a central pancreatectomy in 9 (1%). The distribution of dysplastic changes and invasive cancer among the cohort was as follows: low-grade dysplasia in 87 (14%), intermediate-grade dysplasia in 206 (33%), high-grade dysplasia in 140 (23%), and IPMN-associated PDAC in 183 (30%) patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics of 616 resected IPMN by final pathology

| Total N = 616 | Low-intermediate dysplasia 293 (47%) | High-grade dysplasia 140 (23%) | Invasive carcinoma 183 (30%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 70 (62–76) | 69 (60–74) | 72 (64–78) | 70 (61–77) |

| Gender, male | 315 (51) | 139 (47) | 74 (53) | 102 (56) |

| Presence of symptoms | 368 (60) | 136 (46) | 85 (61) | 147 (80) |

| Weight loss | 155 (25) | 42 (14) | 35 (25) | 78 (43) |

| Abdominal pain | 266 (43) | 116 (40) | 65 (46) | 85 (46) |

| Jaundice | 89 (15) | 13 (4) | 7 (5) | 69 (38) |

| Type of resection | ||||

| Whipple | 405 (66) | 183 (62) | 111 (79) | 111 (61) |

| Distal | 141 (23) | 93 (32) | 16 (11) | 32 (17) |

| Total | 61 (10) | 9 (3) | 12 (9) | 40 (22) |

| Central | 9 (1) | 8 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 |

Clinicopathologic comparison of high-grade IPMN and IPMN-associated PDAC

The clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients with IPMN with high-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma are compared in Table 2. The median age was 72 years old (IQR, 64–78) for patients with a non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia and 70 years old (IQR, 61–77) in those found to have IPMN-associated PDAC (95% CI, −0.17 – 0.08, p = 0.417). Compared to patients with non-invasive IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia, those with invasive carcinoma were more commonly symptomatic (80% vs. 61%, OR: 2.64, 95% CI, 1.60–4.35, p < 0.001). Specifically, weight loss (43% vs. 25%, OR: 2.23, 95% CI, 1.37–3.61, p = 0.001), and jaundice (38% vs. 5%, OR: 11.5, 95% CI, 5.07–26.06, p < 0.001) were more commonly associated with invasive carcinoma.

Table 2.

Characteristics of IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma

| High-grade dysplasia 140 (43%) | Invasive carcinoma 183 (57%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 72 (64–78) | 70 (61–77) | 0.417 |

| Gender, male | 74 (53) | 102 (56) | 0.607 |

| Presence of symptoms | 85 (61) | 147 (80) | <0.001 |

| Weight loss | 35 (25) | 78 (43) | 0.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 65 (46) | 85 (46) | 0.997 |

| Jaundice | 7 (5) | 69 (38) | <0.001 |

| Type of resection | <0.001 | ||

| Whipple | 111 (79) | 111 (61) | |

| Distal | 16 (11) | 32 (17) | |

| Total | 12 (9) | 40 (22) | |

| Central | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0 | 97 (53) | <0.001 |

| Perineural invasion | 0 | 107 (58) | <0.001 |

| Vascular invasion | 0 | 60 (33) | <0.001 |

| Positive margina | 32 (23) | 62 (34) | 0.032 |

Margin involvement was defined as presence of IPMN with any grade of dysplasia or invasive adenocarcinoma at the resection line.

The median tumor size of the invasive component of the 183 IPMN-associated PDACs was 3.5 cm (IQR 2.5–5), and the median size of the non-invasive IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia was 2.9 cm (IQR 2–4). In patients with IPMN-associated PDAC, the invasive carcinoma was classified as tubular in 139 (76%) and colloid in 44 (24%). Among the entire cohort of patients with IPMN-associated PDAC, regional lymph node metastases were identified in 97 (53%), microvascular invasion in 60 (33%) and perineural invasion in 107 (58%). When analyzed separately, colloid carcinoma was associated with lower rates of regional lymph node metastases (20% vs. 63%, p < 0.001), microvascular invasion (9% vs. 40%, p < 0.001), and perineural invasion (36% vs. 65%, p < 0.001) compared to IPMN-associated tubular adenocarcinoma (Table 3). As expected, patients with non-invasive IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia had no lymph node metastasis, vascular or perineural invasion identified.

Table 3.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of two histologic types of IPMN-associated PDAC

| Tubular carcinoma 139 (76%) | Colloid carcinoma 44 (24%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 71 (62–77) | 69 (59–75) | 0.132 |

| Gender, Male | 74 (53) | 28 (64) | 0.229 |

| Tumor sizea, median (IQR), cm | 5 (3.7–8) | 3.5 (2.5–5) | <0.001 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 88 (63%) | 9 (20%) | <0.001 |

| Perineural invasion | 91 (65%) | 16 (36%) | <0.001 |

| Vascular invasion | 56 (40%) | 4 (9%) | <0.001 |

| Positive margin | 55 (40) | 7 (16%) | 0.006 |

The size represents the invasive component of IPMN.

In patients undergoing resection of IPMN-associated PDAC, a resection margin positive for invasive carcinoma or high-grade dysplasia was observed in 62 (34%). The class of margin was distributed as follows; R1 in 39 (39/183, 21%), R2 in 4 (4/183, 2%), invasive carcinoma within 1 mm from margin (also considered a positive resection margin) in 13 (7%), high-grade dysplasia at resection margin in 6 (3%) and an R0 resection in 87 (48%) patients. Also an additional resection was performed in 14 (14/183, 8%) based on the result of an intraoperative assessment of the margin status and extension to total pancreatectomy was performed in 20 (11%). The distribution of grade of dysplasia at the margin was as follows for patients undergoing resection of a non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia; High-grade dysplasia in 12 (12/140, 8%), intermediate-grade dysplasia in 7 (7/140, 5%), low-grade dysplasia in 4 (4/140, 3%), PanIN in 2 (2%), and unknown dysplasia at margin in 7 (5%). A positive margin of any grade was more common for resection of IPMN-associated PDAC in comparison to IPMN with high-grade dysplasia in which 32 (23%) patients had a positive resection margin (OR: 1.73, 95% CI, 1.05–2.85, p = 0.032).

Natural history of resected IPMN

A total of 374 (61%) patients had more than 6 months of follow-up after resection of their IPMN. The median follow-up for this cohort was 28 months (IQR, 13–55 months). The distribution of dysplasia and invasive cancer among this group was as follows; 188 (50%) had low/intermediate-grade dysplasia, 89 (24%) had high-grade dysplasia and 97 (26%) had an IPMN-associated PDAC.

Three of the 20 (3/20, 15%) patients who underwent resection of colloid carcinoma developed distant metastases, as did 28 of the 77 (28/77, 36%) patients who underwent resection of IPMN-associated tubular PDAC (p = 0.080). A regional recurrence was identified in 4 (4/20, 20%) patients with colloid carcinoma and 9 (9/77, 12%) patients with IPMN-associated tubular adenocarcinoma. Two (10%) patients with colloid carcinoma and 10 (13%) patients with tubular carcinoma developed both local and metastatic recurrence. No patient who underwent resection of IPMN with high-grade dysplasia developed a local or systemic recurrence.

In assessment of the pancreatic remnant, at a median follow-up of 28 months no patient who underwent resection of an IPMN-associated PDAC developed a clinically significant new IPMN or a second invasive cancer. Nor did any patient develop a clinically significant progression of an existing IPMN in their pancreatic remnant. This is in contrast to patients who underwent resection of a non-invasive IPMN. Specifically, the development of a new IPMN or progression of an existing IPMN was observed in the remnant pancreas in 21 patients (24%) with high-grade dysplasia. This was significantly different from the changes in the remnant pancreas in patients who underwent resection of an IPMN-associated adenocarcinoma (58%, OR: 4.42, 95% CI, 2.34–8.33, p < 0.001), but was similar to those who underwent resection of a non-invasive IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia. In this latter group, 22% (n = 42) developed a new lesion or had progression of an existing lesion (OR: 0.93, 95% CI, 0.51–1.69, p = 0.816).

In the 21 patients who underwent resection of a non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia, the pattern of disease progression included development of a new lesion in 14 (14/21, 67%) and increase in the cyst size or the main pancreatic duct size in 7 (7/21, 33%). A total of 7 patients with a non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia underwent a re-operation for progressive disease in their remnant pancreas after median time of 54.4 months from the first operation. The pathology after second operation was intermediate-grade dysplasia in 2, high-grade dysplasia in 2, and an IPMN-associated invasive carcinoma in 3 patients. Three patients who originally had a non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia resected subsequently developed metastatic adenocarcinoma from a new primary lesion in their remnant pancreas and did not undergo additional pancreatic resection. The median time to development of an invasive cancer was 47 months for the 6 patients. Among patient with disease progression after resection of a non-invasive IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia, 33 (33/41, 80%) developed a new lesion in their remnant pancreas, and 8 (8/41, 20%) demonstrated an increase in the cyst size or the duct size. Seven patients with a non-invasive IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia underwent re-operation for disease progression. The median time between the two operations was 33 months. The pathology of these resections of the remnant pancreas included PanIN in 1, low/intermediate-grade dysplasia in 3, high-grade dysplasia in 1, and PDAC in 2. Two patients developed a metastatic disease from a second primary lesion and did not undergo pancreatic re-resection. The median time to development of an invasive carcinoma was 69 months for these 4 patients.

The median time to disease progression from the original diagnosis was 28 months for patients who originally had a non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia and 13 months for patients who originally had an IPMN with an associated invasive carcinoma (p = 0.009).

Overall survival

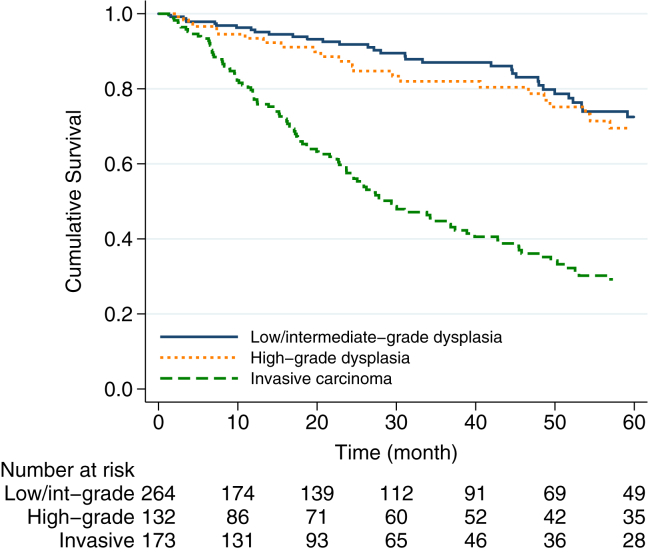

A total of 209 (34%) patients died after median follow-up of 23 months (IQR, 7–51). with an estimated 5-year overall survival rate of 54% (95% CI, 0.48–0.59). The estimated overall 5-year survival rate was 73% (95% CI, 0.63–0.81) for patients with an IPMN with low/intermediate dysplasia, 70% (95% CI, 0.57–0.79) for patients with an IPMN with high-grade dysplasia and 30% (95% CI, 0.22–0.38) for patients with IPMN-associated PDAC. The median overall survival after resection for IPMN with high-grade dysplasia was 92 months, which was similar to median survival after resection of IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia (118 months, HR = 1.46, 95% CI, 0.95–2.24, p = 0.081). In contrast, patients with IPMN with high-grade dysplasia had an improved survival compared to patients with IPMN-associated PDAC (median survival 29 months, HR = 2.71, 95% CI, 1.89–3.89, p < 0.001), (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of patients undergoing surgical resection of IPMN by final pathology

The disease-specific cause of death in patients with resected non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia included: subsequent development of PDAC in 14, cardiovascular disease in 7, non-pancreatic malignant neoplasm in 5, diabetes in 2, pulmonary disease in 2, infection in 2, nephritic syndrome in 1 and unknown cause of dead in 7 patients. A total of 10 patients with high-grade dysplasia who died of pancreatic cancer according to the death index were not identified as having pancreatic cancer on our pattern of recurrence analysis described above. This discrepancy is likely related to the two different data sources used for each analysis. The most likely explanation of additional patients dying of PDAC but not have recurrence identified is that it developed subsequent to their last follow-up at our institution. Overall, 16 patients with an IPMN with high-grade dysplasia developed a metachronous PDAC. In patients who had an IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia the cause of death was PDAC in 3, cardiovascular disease in 9, non-pancreatic neoplasms in 10, stroke in 3, infectious disease in 2, pulmonary disease in 1, renal failure in 1, dementia in 2, fall/poisoning in 3 and unknown cause of death in 10 patients. Among patients with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia 4 patients who developed a PDAC were still alive at the time of follow-up. Three other who died of PDAC were not identified in the pattern of recurrence analysis for the reason described above. In total, 7 patients with IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia developed metachronous PDAC. For patients with resected IPMN-associated PDAC the causes of death were PDAC in 87 (71%), non-pancreatic malignant neoplasm in 7, cardiovascular event in 5, infectious disease in 7 and unknown cause in 17 patients.

Disease-specific survival

At the time of follow-up a total of 209 patients were identified as dead. Of these patients the cause of death was known in a total of 175 (84%) patients. The cause of death was pancreatic neoplasm in 108 (108/209, 52%) patients. The estimated 5-year disease-specific survival rate was 71% (95% CI, 0.66–0.76) for the entire cohort. Among patients who underwent resection for a non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia the estimated 5-year disease-specific survival rate was 84%, which was significantly lower in comparison to a 97% rate in patients underwent resection of an IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia (HR = 0.12, 95% CI, 0.03–0.41, p = 0.001); but markedly superior to patients with IPMN-associated PDAC, who had a 39% disease-specific 5-year survival rate (HR = 5.18, 95% CI, 2.99–8.95, p < 0.001), (Fig. 3). Among patients with IPMN-associated PDAC the histology was tubular adenocarcinoma in 76% (139/183), and colloid carcinoma in 24% (44/183). The estimated 5-year disease-specific survival rate was 59% (95% CI, 0.37–0.75) for patients with colloid carcinoma and 33% (95% CI, 0.23–0.43) for the patients with tubular adenocarcinoma. Compared to patients with high-grade dysplasia, both colloid carcinoma (HR = 2.79, 95% CI, 1.31, 5.91, p = 0.008) and tubular carcinoma (HR = 6.04, 95% CI, 3.46, 10.54, p < 0.001) were associated with worse disease-specific survival, (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

The disease-specific survival estimated by Kaplan–Meier for the patients undergoing pancreatic resection for IPMN

Figure 4.

Disease-specific survival estimates for patients undergoing surgical resection for IPMN with high-grade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma

Factors associated with disease-specific survival

We further examined possible predictive factors associated with disease-specific survival. On univariate analysis, survival rates significantly decreased as the grade of dysplasia increased (see above). We also found that older patient age at the diagnosis (p = 0.006), and main/mixed IPMN type (p = 0.002) were associated with worse survival. On multivariate analysis, older patients' age (HR = 1.03, 95% CI, 1.01–1.05, p = 0.005) and higher grades of dysplasia were independent factors associated with a lower disease-specific survival. Compared to patients with non-invasive IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia, patients with non-invasive IPMNs with low/intermediate dysplasia had an improved disease-specific survival (HR = 0.12, 95% CI, 0.04–0.44, p = 0.001); and IPMN-associated PDAC was associated with worse disease-specific survival (HR = 6.17, 95% CI, 3.45–11.04, p < 0.001), (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with disease-specific survival in patients undergoing surgical resection for IPMN

| 5-year disease-specific survival |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | 95% CI | HR | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Age | – | – | 1.02 | 0.006 | 1.03 | 1.01, 1.05 | 0.005 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 66% | 0.58, 0.74 | Ref. | – | – | – | |

| Male | 76% | 0.68, 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.184 | |||

| IPMN dysplasia | |||||||

| High-grade | 84% | 0.72, 0.91 | Ref. | Ref. | – | ||

| Low/intermediate-grade | 97% | 0.91, 0.99 | 0.12 | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.04, 0.44 | 0.001 |

| Invasive carcinoma | 39% | 0.29, 0.48 | 5.18 | <0.001 | 6.17 | 3.45, 11.04 | <0.001 |

| Margin status | |||||||

| Negative | 74% | 0.67, 0.79 | Ref. | Ref. | – | ||

| Positive | 66% | 0.57, 0.74 | 1.43 | 0.071 | 1.32 | 0.89, 1.96 | 0.172 |

| IPMN duct-type | |||||||

| Branch duct type | 78% | 0.70, 0.83 | Ref. | Ref. | – | ||

| Main/Mixed-type | 65% | 0.56, 0.72 | 1.85 | 0.002 | 0.68 | 0.45, 1.03 | 0.078 |

Factors associated with development of PDAC in patients with non-invasive IPMN

A total of 16 patients with non-invasive IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia and 7 patients with non-invasive IPMNs with low/intermediate dysplasia developed PDAC after surgical resection. By univariate analysis older age (p < 0.040), and high-grade dysplasia (p < 0.001) were associated with development of PDAC. Multivariate analysis identified high-grade dysplasia as an independent predictor of development of PDAC after surgical resection of a non-invasive IPMN (OR = 8.82, 95% CI, 2.56–30.43, p = 0.001), (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate and Multivariate analysis of factors associated with development of PDAC in patients with non-invasive IPMNs (IPMNs with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia or high-grade dysplasia)

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Age | 1.04 | 0.99, 1.08 | 0.040 | – | – | – |

| Gender, Male | 1.54 | 0.64, 3.69 | 0.330 | 2.76 | 0.85, 9.93 | 0.090 |

| IPMN size | 1.15 | 0.95, 1.39 | 0.814 | – | – | – |

| IPMN dysplasia | ||||||

| Low/intermediate-grade | Ref. | – | Ref. | |||

| High-grade | 5.27 | 2.08, 13.32 | <0.001 | 8.82 | 2.56, 30.43 | 0.001 |

| Positive margin | 1.09 | 0.41, 2.88 | 0.868 | – | – | – |

| IPMN type | ||||||

| Branch-duct type | Ref. | – | Ref. | |||

| Main/Mixed-type | 0.98 | 0.39, 2.40 | 0.964 | 0.38 | 0.12, 2.26 | 0.113 |

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that the natural history of resected IPMN-associated PDAC is significantly different than that of non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia. No patient with non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia went on to develop metastases (systemic recurrence) or local/regional recurrence in the resection bed. This is in stark contrast to IPMN-associated PDAC in which 58% of patients developed either systemic or localized recurrence similar to what has been reported for non-IPMN-associated PDAC. These findings underscore the importance of not combining IPMN-associated PDAC with non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia under the term “malignancy” when reporting on the outcome following resection.

Similar to our current work, previous studies reported disease progression in the remnant pancreas in 0–38% of patients with IPMN with high-grade dysplasia14, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 and a recurrence rate between 12% and 65% in patients with IPMN-associated PDAC.14, 22, 23, 24, 27, 29, 30 We previously reported that overall 17% of patients with non-invasive IPMN developed progression within the remnant pancreas.28 Specifically, 21% (9 of 43) of patients with high-grade dysplasia developed a progression similar to our current study. Chari et al. in a study of 113 patients reported disease progression in 14% of patients with high-grade dysplasia in a median time of 37 months and recurrence in 65% IPMN-associated PDAC after 18 months.23 Also similar to our current study, we have previously reported that colloid carcinoma has a better survival than to IPMN-associated tubular adenocarcinoma.31 Despite the favorable survival of colloid carcinoma, it still represents a malignancy and carries a worse prognosis than patients with high-grade dysplasia arising from in an IPMN.

It is important to point out however, that IPMN with high-grade dysplasia does appear to be a marker for more aggressive disease in that the overall disease-specific survival is significantly lower than for resected IPMN with low- or intermediate -grade dysplasia. This difference is, in part, accounted for by a higher risk of the remnant pancreas to develop PDAC in patients with initially resected IPMN with high-grade dysplasia (11%) compared to IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia (2%). Consistent with our findings, Kang et al. have reported progression to invasive carcinoma in 1.6% of patients who underwent resection for an IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia after 52 months and in 9% of patients following resection of an IPMN with high-grade dysplasia after 29 months.29 The biological basis behind this interesting observation is not revealed by our study but has several potential explanations. First, the presence of high-grade dysplasia in the primary specimen may be a marker for a more aggressive IPMN phenotype in which the entire gland is at increased risk of developing a cancer. Second, high-grade dysplasia may simply be a marker for having identified the events of tumorogenesis at a later time in development. Finally, it may be a result of intraductal spread of the primary lesion with continued progression over time. Regardless of which of these possibilities account for the unique behavior of non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia, this finding has clinical implications for surgical decision-making and post-operative follow-up of this cohort.

Taken together the observations of the lack of systemic and local/regional recurrence for non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia along with the increased risk of development of PDAC in the pancreatic remnant have important implications in clinical decision-making. Will some patients undergoing resection of high-grade dysplasia as determined by intraoperative pathological assessment benefit from total pancreatectomy? Our work cannot directly address this question but it certainly raises the possibly that it should be considered on a selected basis. In particular, a relatively young or fit patient undergoing resection of IPMN with high-grade dysplasia with an expected long survival may derive benefit in terms of PDAC prevention from a total pancreatectomy. It should be pointed out that recent works have suggested that post-operative mortality, morbidity and quality of life after total pancreatectomy are equivalent to pancreaticoduodenectomy.32, 33, 34, 35

Our results have implications for the follow-up of patients with resected non-invasive IPMN. In our series, 11% of patients with IPMN with high-grade dysplasia progressed to a new PDAC at a median of 47 months. The time to development of PDAC in resected non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia ranged from as early as 23 months to as late as 119 months. For IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia the range was 50–102 months. Moreover, 3 patients underwent an additional resection for progression and were found to have IPMN with high-grade dysplasia – the earliest time to progression was 30 months. This rate of progression to high-grade dysplasia and PDAC is higher than what has been reported for patients not undergoing resection of IPMN and likely reflects a population of patients selected for more aggressive biology. The timing and rate of development of high-grade dysplasia and PDAC in this population underscores the need for long-term follow-up on a relatively frequent basis. These findings call into question the recommendations of the recent American Gastroenterological Association Institute (AGA) guidelines that recommend patients with a resected IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia should undergo surveillance of their remaining pancreas every 2 years.36 Our data would also suggest that this frequency of surveillance may be insufficient and we would recommend imaging studies every 6 months for patients with resected IPMN with high-grade dysplasia. The recent AGA guidelines also suggest no follow-up for the IPMNs with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia. Our results are in stark contradiction to this recommendation since in our cohort we observed a progression to a new PDAC in 2% of patients with IPMN harboring low/intermediate-grade dysplasia after a median of 69 months. Although the risk of development of an invasive cancer is lower in IPMNs with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia than IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia, the risk is relatively high compared to the general population. We suggest that close, long-term surveillance of patients with IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia is necessary after surgical resection.

Another intriguing possibility for consideration in clinical management of non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia comes from the management of breast neoplasia in which breast sparing surgery is combined with adjuvant external beam radiation for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).37 In this population standard therapy often includes lumpectomy followed by adjuvant irradiation. This raises the question of whether partial pancreatectomy followed by radiation of the margin and/or remaining pancreas should be studied in the context of resected IPMN with high-grade dysplasia.38, 39

In the disease-specific survival of patients with resected non-invasive IPMN, we noted that a significant number of patients died of other cancers. We cannot determine from our dataset whether or not this is higher than expected for a similarly aged population. However, it is important to note that it has been suggested by others that IPMNs are associated with an increased risk of extrapancreatic neoplasms and malignancies including colon polyps and colorectal cancer.40 IPMNs and colon polyps follow a similar pattern of progression from adenoma or dysplasia to invasive carcinoma. A common genetic and epigenetic alteration is shown to be involved in the two diseases carcinogenesis including GNAS and KRAS mutations.41, 42, 43

In conclusion, non-invasive IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia have a distinct natural history compared to IPMN-associated PDAC. The survival after resection of non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia is superior to IPMN-associated invasive cancer as a result of the absence of locoregional and systemic recurrence. We demonstrate that non-invasive IPMN with high-grade dysplasia should not be considered a malignant entity. We also demonstrate that compared to patients undergoing resection of an IPMN with low/intermediate-grade dysplasia, those with an IPMN with high-grade dysplasia have an increased risk of the subsequent development of PDAC. These findings have important clinical implications.

Funding sources

None.

Footnotes

This study was presented at the Annual Meeting of the AHPBA, 11-15 March 2015, Miami, Florida.

Contributor Information

Laura D. Wood, Email: ldelong1@jhmi.edu.

Christopher L. Wolfgang, Email: cwolfga2@jhmi.edu.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Shi C., Hruban R.H. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Hum Pathol. 2012 Jan;43:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.04.003. PubMed PMID: 21777948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka M., Fernandez-del Castillo C., Adsay V., Chari S., Falconi M., Jang J.Y. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012 May–Jun;12:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004. PubMed PMID: 22687371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hruban R.H., Takaori K., Klimstra D.S., Adsay N.V., Albores-Saavedra J., Biankin A.V. An illustrated consensus on the classification of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004 Aug;28:977–987. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000126675.59108.80. PubMed PMID: 15252303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hruban R.H., Pitman M.B., Klimstra D.S., American Registry of P, Armed Forces Institute of P . American Registry of Pathology in collaboration with the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; Washington, DC: 2007. Tumors of the pancreas. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohhashi K., Murayama M., Takekoshi T., Ohta H., Ohhashi I. Four cases of mucus secreting pancreatic cancer. Prog Dig Endosc. 1982;20:348–351. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klöppel G., Solcia E., Longnecker D., Capella C., Sobin L. Springer; Berlin: 1996. Histological typing of tumors of the exocrine pancreas; pp. 11–19. World Health Organization International Histological classification of Tumors, 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lennon A.M., Wolfgang C.L., Canto M.I., Klein A.P., Herman J.M., Goggins M. The early detection of pancreatic cancer: what will it take to diagnose and treat curable pancreatic neoplasia? Cancer Res. 2014 Jul 1;74:3381–3389. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0734. PubMed PMID: 24924775. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4085574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sohn T.A., Yeo C.J., Cameron J.L., Hruban R.H., Fukushima N., Campbell K.A. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an updated experience. Ann Surg. 2004 Jun;239:788–797. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000128306.90650.aa. discussion 97–9. PubMed PMID: 15166958. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1356287. Epub 2004/05/29. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahora K., Mino-Kenudson M., Brugge W., Thayer S.P., Ferrone C.R., Sahani D. Branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: does cyst size change the tip of the scale? A critical analysis of the revised international consensus guidelines in a large single-institutional series. Ann Surg. 2013 Sep;258:466–475. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a18f48. PubMed PMID: 24022439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez J.R., Salvia R., Crippa S., Warshaw A.L., Bassi C., Falconi M. Branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: observations in 145 patients who underwent resection. Gastroenterology. 2007 Jul;133:72–79. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.010. quiz 309–10. PubMed PMID: 17631133. Epub 2007/07/17. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aso T., Ohtsuka T., Matsunaga T., Kimura H., Watanabe Y., Tamura K. High-risk stigmata” of the 2012 international consensus guidelines correlate with the malignant grade of branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2014 Nov;43:1239–1243. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000199. PubMed PMID: 25036910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohtsuka T., Kono H., Nagayoshi Y., Mori Y., Tsutsumi K., Sadakari Y. An increase in the number of predictive factors augments the likelihood of malignancy in branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Surgery. 2012 Jan;151:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.009. PubMed PMID: 21875733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt C.M., White P.B., Waters J.A., Yiannoutsos C.T., Cummings O.W., Baker M. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: predictors of malignant and invasive pathology. Ann Surg. 2007 Oct;246:644–651. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a9e5. discussion 51–4. PubMed PMID: 17893501. Epub 2007/09/26. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnelldorfer T., Sarr M.G., Nagorney D.M., Zhang L., Smyrk T.C., Qin R. Experience with 208 resections for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Arch Surg. 2008 Jul;143:639–646. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.7.639. discussion 46. PubMed PMID: 18645105. Epub 2008/07/23. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sohn T.A., Yeo C.J., Cameron J.L., Iacobuzio-Donahue C.A., Hruban R.H., Lillemoe K.D. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an increasingly recognized clinicopathologic entity. Ann Surg. 2001 Sep;234:313–321. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200109000-00005. discussion 21–2. PubMed PMID: 11524584. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1422022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamao K., Ohashi K., Nakamura T., Suzuki T., Shimizu Y., Nakamura Y. The prognosis of intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000 Jul-Aug;47:1129–1134. PubMed PMID: 11020896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagai K., Doi R., Kida A., Kami K., Kawaguchi Y., Ito T. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinicopathologic characteristics and long-term follow-up after resection. World J Surg. 2008 Feb;32:271–278. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9281-2. discussion 9–80. PubMed PMID: 18027021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadakari Y., Ienaga J., Kobayashi K., Miyasaka Y., Takahata S., Nakamura M. Cyst size indicates malignant transformation in branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas without mural nodules. Pancreas. 2010 Mar;39:232–236. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bab60e. PubMed PMID: 19752768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salvia R., Crippa S., Falconi M., Bassi C., Guarise A., Scarpa A. Branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: to operate or not to operate? Gut. 2007 Aug;56:1086–1090. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.100628. PubMed PMID: 17127707. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1955529. Epub 2006/11/28. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nara S., Onaya H., Hiraoka N., Shimada K., Sano T., Sakamoto Y. Preoperative evaluation of invasive and noninvasive intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinical, radiological, and pathological analysis of 123 cases. Pancreas. 2009 Jan;38:8–16. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318181b90d. PubMed PMID: 18665010. Epub 2008/07/31. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wasif N., Bentrem D.J., Farrell J.J., Ko C.Y., Hines O.J., Reber H.A. Invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm versus sporadic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a stage-matched comparison of outcomes. Cancer. 2010 Jul 15;116:3369–3377. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25070. PubMed PMID: 20564064. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2902567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salvia R., Fernandez-del Castillo C., Bassi C., Thayer S.P., Falconi M., Mantovani W. Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinical predictors of malignancy and long-term survival following resection. Ann Surg. 2004 May;239:678–685. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124386.54496.15. discussion 85-7. PubMed PMID: 15082972. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1356276. Epub 2004/04/15. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chari S.T., Yadav D., Smyrk T.C., DiMagno E.P., Miller L.J., Raimondo M. Study of recurrence after surgical resection of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2002 Nov;123:1500–1507. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36552. PubMed PMID: 12404225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raut C.P., Cleary K.R., Staerkel G.A., Abbruzzese J.L., Wolff R.A., Lee J.H. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: effect of invasion and pancreatic margin status on recurrence and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006 Apr;13:582–594. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.002. PubMed PMID: 16523362. Epub 2006/03/09. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka M., Chari S., Adsay V., Fernandez-del Castillo C., Falconi M., Shimizu M. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17–32. doi: 10.1159/000090023. PubMed PMID: 16327281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White R., D'Angelica M., Katabi N., Tang L., Klimstra D., Fong Y. Fate of the remnant pancreas after resection of noninvasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. J Am Coll Surg. 2007 May;204:987–993. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.040. discussion 93–5. PubMed PMID: 17481526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Passot G., Lebeau R., Hervieu V., Ponchon T., Pilleul F., Adham M. Recurrences after surgical resection of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: a single-center study of recurrence predictive factors. Pancreas. 2012 Jan;41:137–141. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318222bc9c. PubMed PMID: 22076564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He J., Cameron J.L., Ahuja N., Makary M.A., Hirose K., Choti M.A. Is it necessary to follow patients after resection of a benign pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm? J Am Coll Surg. 2013 Apr;216:657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.12.026. discussion 65-7. PubMed PMID: 23395158. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3963007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang M.J., Jang J.Y., Lee K.B., Chang Y.R., Kwon W., Kim S.W. Long-term prospective cohort study of patients undergoing pancreatectomy for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: implications for postoperative surveillance. Ann Surg. 2014 Aug;260:356–363. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000470. PubMed PMID: 24378847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim S.C., Park K.T., Lee Y.J., Lee S.S., Seo D.W., Lee S.K. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of 118 consecutive patients from a single center. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:183–188. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1231-8. PubMed PMID: 18392712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poultsides G.A., Reddy S., Cameron J.L., Hruban R.H., Pawlik T.M., Ahuja N. Histopathologic basis for the favorable survival after resection of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm-associated invasive adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2010 Mar;251:470–476. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181cf8a19. PubMed PMID: 20142731. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3437748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe Y., Ohtsuka T., Matsunaga T., Kimura H., Tamura K., Ideno N. Long-term outcomes after total pancreatectomy: special reference to survivors' living conditions and quality of life. World J Surg. 2015 May;39:1231–1239. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-2948-1. PubMed PMID: 25582768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller M.W., Friess H., Kleeff J., Dahmen R., Wagner M., Hinz U. Is there still a role for total pancreatectomy? Ann Surg. 2007 Dec;246:966–974. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c2ca3. discussion 74–5. PubMed PMID: 18043098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reddy S., Wolfgang C.L., Cameron J.L., Eckhauser F., Choti M.A., Schulick R.D. Total pancreatectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: evaluation of morbidity and long-term survival. Ann Surg. 2009 Aug;250:282–287. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ae9f93. PubMed PMID: 19638918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crippa S., Tamburrino D., Partelli S., Salvia R., Germenia S., Bassi C. Total pancreatectomy: indications, different timing, and perioperative and long-term outcomes. Surgery. 2011 Jan;149:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.04.007. PubMed PMID: 20494386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vege S.S., Ziring B., Jain R., Moayyedi P., Clinical Guidelines C. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015 Apr;148:819–822. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.015. quize12–3. PubMed PMID: 25805375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moran M.S., Bai H.X., Harris E.E., Arthur D.W., Bailey L., Bellon J.R. ACR appropriateness criteria((R)) ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast J. 2012 Jan-Feb;18:8–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01197.x. PubMed PMID: 22107336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herman J.M., Chang D.T., Goodman K.A., Dholakia A.S., Raman S.P., Hacker-Prietz A. Phase 2 multi-institutional trial evaluating gemcitabine and stereotactic body radiotherapy for patients with locally advanced unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2015 Apr 1;121:1128–1137. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29161. PubMed PMID: 25538019. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4368473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herman J.M., Swartz M.J., Hsu C.C., Winter J., Pawlik T.M., Sugar E. Analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: results of a large, prospectively collected database at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Clin Oncol – Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2008 Jul 20;26:3503–3510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8469. PubMed PMID: 18640931. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3558690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eguchi H., Ishikawa O., Ohigashi H., Tomimaru Y., Sasaki Y., Yamada T. Patients with pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms are at high risk of colorectal cancer development. Surgery. 2006 Jun;139:749–754. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.11.008. PubMed PMID: 16782429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sessa F., Solcia E., Capella C., Bonato M., Scarpa A., Zamboni G. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumours represent a distinct group of pancreatic neoplasms: an investigation of tumour cell differentiation and K-ras, p53 and c-erbB-2 abnormalities in 26 patients. Virchows Arch. 1994;425(4):357–367. doi: 10.1007/BF00189573. PubMed PMID: 7820300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leslie A., Carey F.A., Pratt N.R., Steele R.J. The colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Br J Surg. 2002 Jul;89(7):845–860. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02120.x. PubMed PMID: 12081733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fecteau R.E., Lutterbaugh J., Markowitz S.D., Willis J., Guda K. GNAS mutations identify a set of right-sided, RAS mutant, villous colon cancers. PloS One. 2014;9:e87966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087966. PubMed PMID: 24498230. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3907576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]