Abstract

Background

Accurate assessment of characteristics of tumor and portal vein tumor thrombus is crucial in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Aims

Comparison of the three-dimensional imaging with multiple-slice computed tomography in the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus.

Method

Patients eligible for surgical resection were divided into the three-dimensional imaging group or the multiple-slice computed tomography group according to the type of preoperative assessment. The clinical data were collected and compared.

Results

74 patients were enrolled into this study. The weighted κ values for comparison between the thrombus type based on preoperative evaluation and intraoperative findings were 0.87 for the three-dimensional reconstruction group (n = 31) and 0.78 for the control group (n = 43). Three-dimensional reconstruction was significantly associated with a higher rate of en-bloc resection of tumor and thrombus (P = 0.025). Using three-dimensional reconstruction, significant correlation existed between the predicted and actual volumes of the resected specimens (r = 0.82, P < 0.01), as well as the predicted and actual resection margins (r = 0.97, P < 0.01). Preoperative three-dimensional reconstruction significantly decreased tumor recurrence and tumor-related death, with hazard ratios of 0.49 (95% confidential interval, 0.27–0.90) and 0.41 (95% confidential interval, 0.21–0.78), respectively.

Conclusion

For hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus, three-dimensional imaging was efficient in facilitating surgical treatment and benefiting postoperative survivals.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer and the third-leading cause of cancer-related death in the world.1 HCC has a great propensity to invade the portal venous system, leading to the formation of portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT). PVTT is the most important poor prognostic factor, being found in 60–90% of patients diagnosed to have advanced liver cancer in China.2 Although Sorafenib was recommended by the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) guideline as the only therapy for these patients, recent studies have shown that surgical resection offers a more promising prognosis in selected HCC patients with PVTT.3, 4, 5

Before operation, the characteristics of the primary tumor and the PVTT should be carefully evaluated. The primary tumor should be resected with an adequate resection margin and an adequate residual liver remnant should be preserved to avoid postoperative liver failure. Moreover, the PVTT can either be en-bloc resected together with the primary tumor, or removed by thrombectomy according to its location and extent.6, 7 The evaluation of such an operation nowadays is usually done on conventional two-dimensional (2D) multiple-slice computed tomography (MSCT).

The recent development of three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction has been shown useful in preoperative planning for hepatectomy by providing precise information on the future liver remnant and the tumor-free margin.8, 9, 10, 11 3D reconstruction offers better understanding of the tumor and PVTT characteristics when compared with 2D imaging. The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of 3D reconstruction in optimizing diagnosis and surgical treatment of HCC patients with PVTT, when compared with conventional 2D MSCT.

Patients and methods

This non-randomized cohort study with prospectively collected data was carried out retrospectively in the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, Shanghai, China, from June 2012 to June 2014. The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all patients for their data to be used for clinical research.

The diagnosis of HCC was based on the noninvasive criteria in accordance with the European Association for the Study of Liver guidelines.12 All HCC patients underwent routine three-phase dynamic MSCT examination after hospital admission. A diagnosis of PVTT was made when there was presence of low-attenuation intraluminal masses that expanded the portal vein, or when there were filling defects in the portal venous system as determined on MSCT images.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were HCC patients aged from 18 to 70 years; presence of PVTT confirmed by preoperative MSCT examination; resectable lesion in the liver with adequate hepatic functional reserve as measured by imaging and laboratory tests. The exclusion criteria were patients with a previous history of other cancer; severe co-existing systemic disease; or had received previous chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

The 3D reconstruction was available in our center in June 2012. A detail discussion was made with all the patients on the pros and cons of the 3D imaging reconstruction, including the extra-time consumed on the procedure and the potential risk of providing inaccurate information. Patients who consented to the 3D reconstruction were entered into the 3D reconstruction group. The remaining patients formed the MSCT group. The sole difference between the groups was determined by the patient's willingness to receive 3D reconstruction. The rest of the preoperative evaluation and the treatment strategy were the same throughout the study period.

Process of spectral CT examination and 3D imaging reconstruction

The MSCT imaging provided the fundamental information for the 3D reconstruction process. The MSCT images were obtained using a spectral CT (Discovery CT750 HD, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA). The scanning parameters used for the CT examination were as follows: a slice thickness of 1.25 mm, a pitch of 0.984 mm, a 0.6-sec scanning time per rotation, a table speed of 13.5 mm/rotation, and a reconstruction interval of 2 mm. After pre-contrast images were obtained, a triple-phase enhanced scan was performed. The enhanced scan used the spectroscopy scan mode (gemstone spectral imaging, GSI). 80 ml of the compound meglumine diatrizoate injection (Xudong Haipu Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, Shanghai, China) were infused at a rate of 3.5 ml/s with a power injector. The arterial phase images were obtained at 5 s; the portal phase images at 20 s; and the venous phase images at 70 s after the peak aortic enhancement time.

For patients in the 3D reconstruction group, after the triple-phase contrast CT examination was performed, the image data sets obtained were analyzed using the 3D image processing software (3D Plus Body Visible System, Yorktal Medical, ShenZhen, China). The triple-phase CT images were transported into the 3D post processing system. The images of the tumor, portal vein, PVTT, hepatic vein, hepatic artery and liver parenchyma were extracted and reconstructed individually using a region-growing or level-set technique and were overlapped to create the integrated 3D images. The transparent display employed in the 3D simulation system provided perspective views of the liver and its surrounding vessels. Various functions which included display or hide of different anatomic structures, and rotation and enlargement, allowed detailed understanding of the characteristics of the tumor and the PVTT. All 3D reconstructions were completed within one working day.

Preoperative assessment of the PVTT type

The PVTT was classified according to the Cheng's classification which has been shown to be effective in stratifying HCC patients with PVTT2, 6, 13: type I, tumor thrombus involving segmental or sectoral branches of the portal vein or above; type II, involvement of the right or left portal vein; type III, invasion of the main trunk of portal vein; and type IV, involvement of the superior mesenteric vein.

All 3D/MSCT images were reviewed independently by two surgeons with extensive experience in treating HCC with PVTT to identify the type of PVTT, as well as any other tumor characteristics. If a diagnostic disagreement occurred between the two surgeons, a discussion involving an experienced liver radiologist was carried out to reach to a final decision.

Preoperative simulation of surgical resection in the 3D reconstruction group

In the 3D reconstruction group, we carried out a preoperative simulation of the surgical procedure on the 3D reconstruction model using the build-in analysis package. The resection plane was planned with a resection margin ≥1 cm, while avoiding injury to any non-invaded major vascular or biliary structures. For patients with PVTT confined to the ipsilateral branch of the portal vein (type I/II), as the thrombus was located within the resected region, it was resected en-bloc with the primary tumor. When the thrombus protruded beyond the resection plane, an extended local or anatomic resection was simulated to remove the primary tumor and the PVTT en-bloc, provided that an adequate liver remnant would remain. However, when the PVTT had protruded into the main trunk of the portal vein (type III/IV), hepatectomy with thrombectomy was simulated. The volume of the future liver remnant was calculated during the simulation to make sure that the volume of the liver remnant was adequate to prevent development of post-hepatectomy liver failure.

Surgical procedures

All surgical procedures were carried out by the same group of experienced surgeons. Pringle's maneuver was applied distal to the PVTT to occlude the blood inflow using a clamp/unclamp cycle of 15 min/5 min. Liver resection was carried out using a clamp crushing method.

After mobilization of the liver, the tumor and the PVTT were re-assessed by intraoperative ultrasound. For patients in the 3D reconstruction group, hepatectomy was carried out following the simulation resection plan by the 3D reconstruction system which was finally adjusted by intraoperative findings. In the MSCT group, the resection plan was determined mainly based on intraoperative findings. The type of liver resection was determined according to the tumor and the PVTT characteristics. For patients with a type III/IV PVTT, thrombectomy was carried out after removal of the primary tumor. The thrombus was extracted from the opened stump of the portal vein at the resection plane. Occasionally, if the thrombus could not be taken out from the opened stump because of its size, the main portal trunk was exposed and clamped distal to the thrombus, then a longitudinal incision was made on the anterior wall of the portal vein to remove the tumor thrombus under direct vision. After extraction of the PVTT, the venous lumen was flushed with normal saline to remove any potential residual lesions. Then the stump or the incision in the main portal vein was closed using a continuous suture.

Evaluation of reliability of the 3D reconstruction system

The intraoperative findings of the PVTT type was compared with the PVTT type based on the 3D reconstruction or the MSCT, to assess the reliability of each of these techniques in classifying the PVTT type. After resection, the surgical specimen was weighed before any pathological examination. The volume of the resected specimen was estimated by assuming that 1 ml of specimen was equal to 1 g tissue. It was then compared with the predicted liver resection volume to validate the reliability of the simulation system on volume estimation. The simulated surgical margin was also compared with the actual margin as measured in the pathological examination of the resected specimens.

Follow-up

All patients were followed-up by the same team of surgeons once a month during the first postoperative year and at 3 month intervals thereafter. At each follow-up visit, serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) and ultrasound were routinely carried out. Contrast MSCT or magnetic resonance imaging was performed once HCC recurrence was suspected. Patients were considered to have non-curative resection instead of having HCC recurrence if they had persistently elevated AFP levels and/or had new lesions found in the liver or other organs within 1 month of resection. Patients with HCC recurrence were treated with repeat resection or local ablative therapy if technically possible. Trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) was the first choice for multiple intrahepatic recurrences which were not resectable. For patients with distal metastasis or recurrent PVTT, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or sorafenib was given. Symptomatic treatment was given for patients with advanced diseases, poor liver function, or poor general condition.

Statistics

The linear weighted κ value between the preoperatively assessed PVTT type based on 3D reconstruction or MSCT images and the PVTT type confirmed by intraoperative and pathological findings was calculated to measure the degree of reliability of each imaging technique. The standard for strength of agreement for the κ value was: ≤0 indicates poor agreement; 0.10–0.20, slight; 0.21–0.40, fair; 0.41–0.60, moderate; 0.61–0.80, substantial and 0.81–1 almost perfect agreement.14

The correlations between the preoperative examination and the final diagnosis were presented as scatter plots and were analyzed using the Pearson test. Continuous and categorized data were compared between the 3D reconstruction and the MSCT groups using the Pearson chi-square test, the Fisher's exact test, or the Student's t test, as appropriate. Patients' disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and their comparison was performed using the log-rank test. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors influencing DFS and OS. Only factors that were significant on univariate analysis were included into multivariate analysis, using a stepwise forward Cox proportional hazards regression model. All calculations were performed using Stata 12.0 software (StataCorp, Texas 77845 USA). A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

During the study period, 105 consecutive HCC patients with PVTT underwent surgical resection in our department. Of the 105 patients, 31 were excluded from this study, including previous radiotherapy/TACE in 23, diagnostic disagreement in 2 and incomplete data in 6 patients. Finally, 74 patients were included in this study (the 3D reconstruction group, n = 31; the MSCT group, n = 43).

The detailed baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1. Most of the parameters were comparable between the two groups, except in the MSCT group there was a significant higher level of AFP concentration. The proportions of the different PVTT types (confirmed during operation) were also comparable between the groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of the clinicopathologic features between patients who received three-dimensional imaging and multiple-slice computed tomography examination

| Clinicopathologic features | 3D imaging (n = 31) | MSCT (n = 43) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD), range | 50 ± 10.6 (33–70) | 48 ± 10.0 (31–75) | 0.407 |

| Gender (male) | 24 | 38 | 0.223 |

| Viral serology | |||

| Positive for HBsAg | 26 | 35 | 1.000 |

| Positive for HBeAg | 5 | 4 | 0.478 |

| Positive HBV DNA load (>500 copies/ml) | 12 | 14 | 0.628 |

| Liver functional status (n) | |||

| Child-Pugh grade A | 27 | 37 | 1.000 |

| Child-Pugh grade B | 4 | 6 | |

| AFP level (ng/ml), range | 530.5 (5–1210) | 794.5 (3–1210) | 0.008* |

| Tumor diameter (cm) | 9.5 ± 3.6 | 10.4 ± 3.8 | 0.307 |

| Tumor number | |||

| Single | 27 | 40 | 0.443 |

| Multiple | 4 | 3 | |

| Confirmed PVTT type | |||

| I | 5 | 5 | 0.665 |

| II | 11 | 20 | |

| III | 11 | 15 | |

| IV | 4 | 3 | |

| Liver cirrhosis | 18 | 19 | 0.346 |

| Tumor differentiation | |||

| I | 0 | 3 | 0.409 |

| II | 5 | 7 | |

| III | 26 | 33 | |

| Satellite nodule | |||

| Yes | 11 | 15 | 1.000 |

| No | 20 | 28 | |

| Tumor capsule | |||

| Complete | 9 | 8 | 0.612 |

| Incomplete | 7 | 12 | |

| Absence | 15 | 23 | |

3D, three-dimensional; MSCT, multiple-slice computed tomography; AFP, α-fetoprotein; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombosis; SD, standard deviation.

* P < 0.05.

Diagnostic accuracy of the PVTT classification based on 3D reconstruction and MSCT examination

In the 3D reconstruction group, the accuracy of the PVTT classification was 87.1% (27/31). The weighted κ values for comparison between the 3D reconstruction PVTT type and the intraoperative PVTT type was 0.87. In the MSCT group, the diagnostic accuracy of the PVTT type based on the MSCT examination was 81.4% (35/43). The weighted κ values for comparison between the MSCT evaluated PVTT type and the intraoperative PVTT type was 0.78. The detailed data are given in Appendix Table A.

Data of the operative procedure

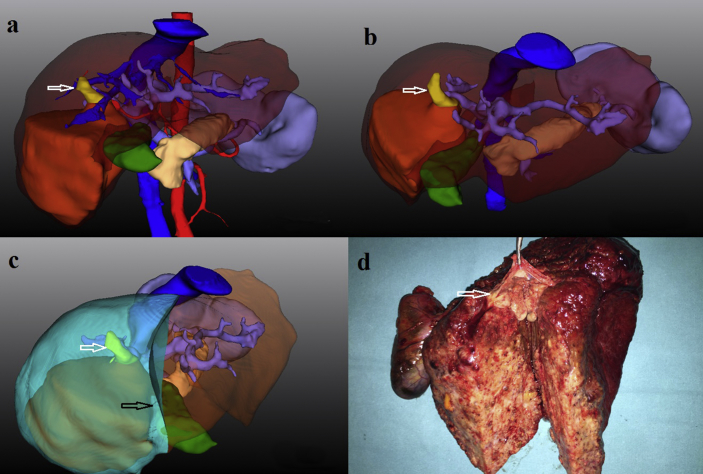

En-bloc resection was carried out in 13 out of 16 patients with the type I/II PVTT in the 3D reconstruction group, with 7 non-anatomic resections and 6 anatomic resections. As shown in Fig. 1, a right hepatectomy was carried out to remove a 7 × 6 cm HCC with a type II PVTT based on the evaluation and simulation of the 3D reconstruction. For patients with the type I/II PVTT in the MSCT group (n = 25), 11 patients underwent en-bloc resection, while the remaining 14 patients underwent hepatectomy and thrombectomy. There were 4 patients (1 in the 3D reconstruction group and 3 in the MSCT group) who underwent palliative resection because of intrahepatic dissemination (n = 2), under-estimated tumor extent (n = 1) and incomplete resection of lymph node metastasis (n = 1). All these 4 patients were treated with postoperative TACE. There was no surgery related mortality. Major postoperative complications (Clavien-Dindo Classification >3) occurred in 9 patients (3 in the 3D reconstruction group and 6 in the MSCT group), which included liver failure (n = 3), bile leak (n = 3), postoperative bleeding (n = 2) and pulmonary infection (n = 1).

Figure 1.

The preoperative evaluation and surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus in a 47-year-old man under the guidance of three-dimensional imaging and reconstruction. a. three-dimensional imaging shows a tumor (dark yellow) with portal vein tumor thrombus (white arrow) located in segment V & VI; b. By employing transparent display of the liver parenchyma and hiding of the hepatic artery and vein, three-dimensional imaging clearly shows that the portal vein tumor thrombus (white arrow) had invaded the right anterior branch and main right branch of the portal vein (type II), while the bifurcation and main trunk of the portal vein was clear; c. An en-bloc resection of the tumor and portal vein tumor thrombus was simulated with a resection line (black arrow); d. The surgical specimen shows the tip of portal vein tumor thrombus (white arrow) was located in the main right branch of portal vein which was resected en-bloc together with the tumor

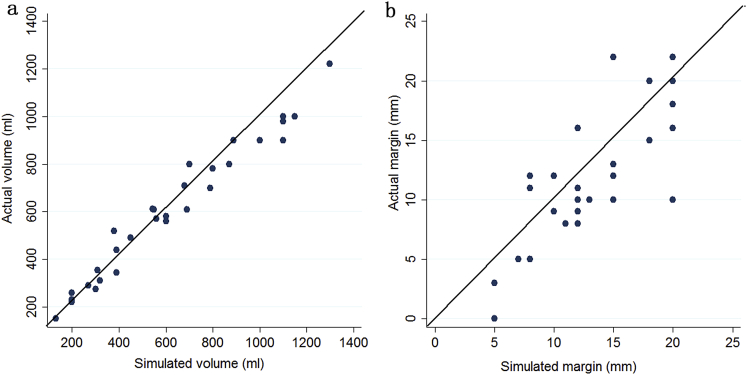

The detailed data of the surgical procedures for the patients who received the different imaging techniques are shown in Table 2. For patients with a type I/II PVTT, the rate of en-bloc resection was significantly higher in the 3D reconstruction group (13/16) than in the MSCT group (11/25) (P = 0.025). The 3D reconstruction group of patients also had significantly shorter operative time (P = 0.026) and hilar clamp time (P = 0.025). In the 3D reconstruction group, a significant correlation existed between the predicted liver resection volumes and the actual volumes of the resected specimens (r = 0.82, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2a). The difference between the estimated volume and the actual volume was 66.2 ± 52.5 ml. A significant correlation was also found between the predicted and the actual resection margins (r = 0.97, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2b). The difference between the predicted and the actual margins was 2.8 ± 2.1 mm.

Table 2.

Comparison of surgical procedures between the three-dimensional imaging group and the multiple-slice computed tomography group

| Data of surgical procedure | 3D imaging (n = 31) | MSCT (n = 43) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of hepatectomya | |||

| En-bloc resection | 13 | 11 | 0.025* |

| Hepatectomy + thrombectomy | 3 | 14 | |

| Curative resection (n) | 30 | 40 | 0.635 |

| Anatomic resection (n) | 11 | 15 | 0.957 |

| Major hepatectomy (n) | 21 | 31 | 0.686 |

| Operating time (min) | 167.4 ± 42.6 | 200.2 ± 71.3 | 0.026* |

| Hilar clamping time (min) | 16.9 ± 5.2 | 19.6 ± 4.7 | 0.025* |

| Intraoperative blood loss (ml) | 732.2 ± 486.1 | 781.4 ± 491.9 | 0.671 |

| Perioperative blood transfusion (n) | |||

| Yes | 15 | 22 | 0.650 |

| No | 18 | 21 | |

| Major postoperative complication (n) | 3 | 6 | 0.726 |

| Mortality | 0 | 0 | – |

| Disease free survival (%) | 0.022* | ||

| 6-month | 56.1 | 33.3 | |

| 12-month | 20.1 | 11.1 | |

| 18-month | 16.5 | 8.3 | |

| 24-month | 12.3 | 5.6 | |

| Overall survival (%) | 0.020* | ||

| 6-month | 90.2 | 88.3 | |

| 12-month | 73.5 | 59.0 | |

| 18-month | 54.0 | 27.1 | |

| 24-month | 40.0 | 18.0 | |

3D, three-dimensional; MSCT, multiple-slice computed tomography.

* P < 0.05.

The comparison was carried out in patients with type I/II PVTT (3D group: n = 16; MSCT group: n = 25).

Figure 2.

a. Correlation between the predicted and the actual resection volume in the three-dimensional reconstruction group. b. Correlation between the predicted and the actual resection margin in the three-dimensional reconstruction group

Follow-up data

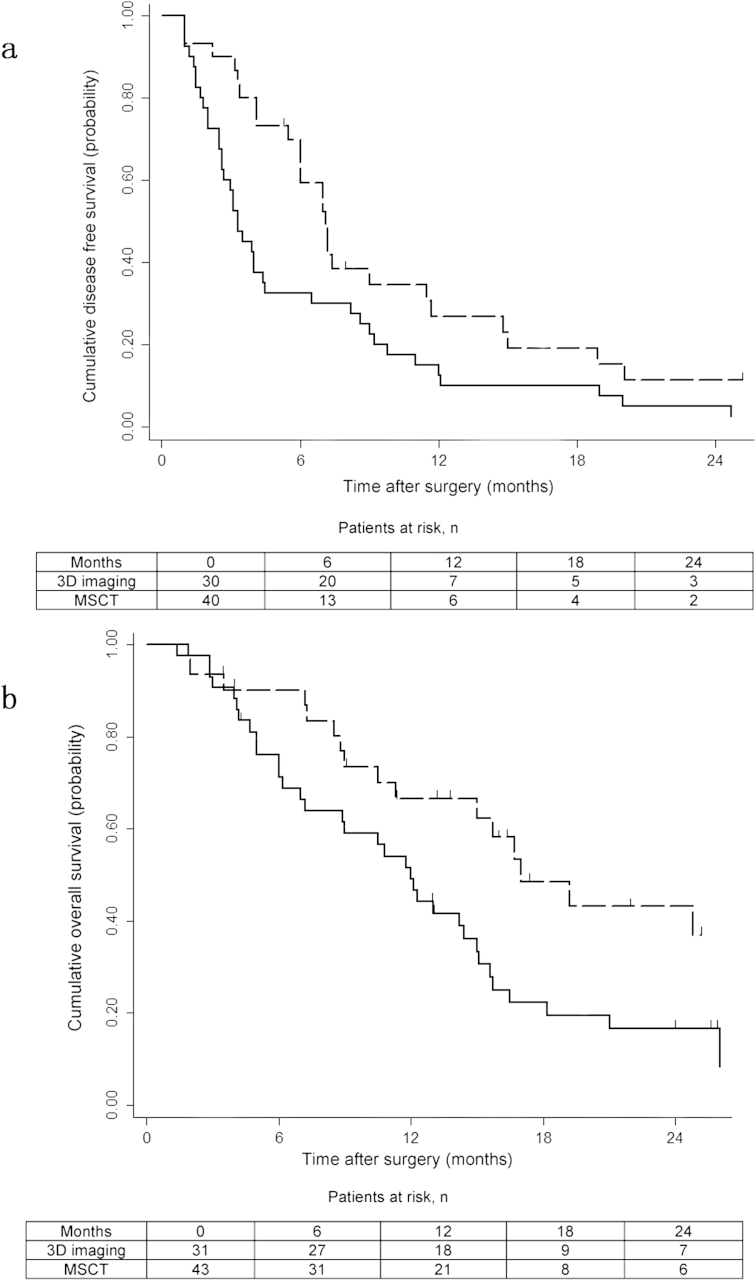

The median follow-up was 14.4 months (interquartile 6.2–17.0 months). Collectively, 68 patients (91.2%) had developed HCC recurrence and 52 patients (70.3%) had died. There were no patients who died of diseases other than progression of HCC. The DFS at 6-, 12-, 18- and 24 months were 56.1%, 20.1%, 16.5% and 12.3% for the 3D reconstruction group vs 33.3%, 11.1%, 8.3% and 5.6% for the MSCT group, respectively (P = 0.022; Fig. 3a). The OS at 6-, 12-, 18- and 24 months were 90.2%, 73.5%, 54.0% and 40.0% for the 3D reconstruction group vs 88.3%, 59.0%, 27.1% and 18.0% for the MSCT group, respectively (P = 0.020, Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

a. Kaplan–Meier analysis of disease free survival in the three-dimensional reconstruction (dashed line) and the multiple-slice computed tomography (black line) groups (log-rank test, P = 0.020; hazard ratio 2.20, 95% confidence interval 1.26–3.85). b. Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival in the three-dimensional reconstruction (dashed line) and the multiple-slice computed tomography (black line) groups (log-rank test, P = 0.020; hazard ratio 2.37, 95% confidence interval 1.27–4.43)

The factors which were significantly associated with HCC recurrence and HCC-related death on univariate Cox regression analysis (Appendix Table B) were introduced into the multivariate Cox model. The results showed the presence of tumor satellites (HR:2.17; 95% CI, 1.12–4.20), prolonged hilar clamp time (HR:1.93; 95% CI, 1.02–3.64) and type III/IV PVTT (HR:2.20; 95% CI, 1.05–4.62) predicated tumor recurrence, while large tumor diameter (HR:2.16; 95% CI, 1.13–4.11), a positive HBV DNA load (HR:2.22; 95% CI, 1.20–4.12) and type III/IV PVTT (HR:3.64; 95% CI, 1.65–8.04) were significantly associated with HCC-related death. Meanwhile, when compared with MSCT examination, the use of preoperative 3D reconstruction significantly reduced both HCC recurrence and HCC-related death with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.49 (95% CI, 0.27–0.90) and 0.41 (95% CI, 0.21–0.78) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with postoperative hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence and hepatocellular carcinoma-related death on multivariate Cox regression analysis

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of recurrence | |||

| HBV DNA load (positive vs negative) | 1.40 | 0.73–2.68 | 0.309 |

| Hilar clamping time (>18 min vs ≤18 min) | 1.93 | 1.02–3.64 | 0.043* |

| Tumor diameter (>10 cm vs ≤10 cm) | 1.57 | 0.77–3.17 | 0.212 |

| Tumor satellites (yes vs no) | 2.17 | 1.12–4.20 | 0.021* |

| PVTT type (III/IV vs I/II) | 2.20 | 1.05–4.62 | 0.038* |

| Surgical type (thrombectomy vs en-bloc resection) | 1.41 | 0.72–2.75 | 0.319 |

| Preoperative examination (3D imaging vs MSCT) | 0.49 | 0.27–0.90 | 0.021* |

| Risk of HCC-related death | |||

| HBV DNA load (positive vs negative) | 2.22 | 1.20–4.12 | 0.011* |

| Hilar clamping time (>18 min vs ≤18 min) | 1.49 | 0.79–2.80 | 0.220 |

| Major postoperative complication | 1.13 | 0.49–2.60 | 0.772 |

| Tumor diameter (>10 cm vs ≤10 cm) | 2.16 | 1.13–4.11 | 0.019* |

| PVTT type (III/IV vs I/II) | 3.64 | 1.65–8.04 | 0.001* |

| Surgical type (thrombectomy vs en-bloc resection) | 0.88 | 0.39–1.98 | 0.753 |

| Preoperative examination (3D imaging vs MSCT) | 0.41 | 0.21–0.78 | 0.007* |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidential interval; HBV, hepatitis B virus; PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombus; 3D, three-dimensional MSCT, multiple-slice computed tomography.

* P < 0.05.

Discussion

PVTT is associated with poor prognosis in HCC patients, with a median survival of only 2.7 months if the patients were untreated.15 Surgical treatment remains the only therapy which may offer a chance of cure, with a median overall survival ranging from 8.9 to 33 months.4, 6, 16, 17, 18 The surgical procedure should be adjusted to achieve a complete resection of both the primary tumor and the tumor thrombus according to the tumor extent and the severity of portal vein invasion.4, 5, 7, 17, 19 Therefore, a precise classification of the PVTT and detailed information on the tumor characteristics are essential for surgical planning. Advances in radiological imaging techniques have helped tremendously in the development of hepatic surgery. Recently, 3D imaging has been reported to facilitate hepatectomy by providing accurate evaluation of liver resection volumes and margins, stereoscopic relationship between tumor and vessels, as well as volumetric estimation of hepatic vein branch drainage area.8, 9, 10, 20 Theoretically, 3D imaging and reconstruction have several advantages over 2D images: the stereoscopic and 360° imaging of the tumor and portal vein system would decrease the sampling and observing error of the 2D images21; the precise simulation of the resection plane and the resected liver volume provide important information for hepatectomy8, 9, 10, 20; the 3D imaging model could also be used as an intraoperative navigation to ensure the safety and clear resection margin of liver resection.20 This is the first study which applied this 3D technique in the diagnosis and surgical treatment of HCC patients with macrovascular PVTT, aiming to identify whether 3D imaging could optimize the surgical procedure and improve the long-term prognosis when compared with conventional MSCT imaging.

In this study which used intraoperative findings as the gold standard, we found the strength of the diagnostic accuracy of PVTT classification based on 3D imaging and reconstruction was almost perfect (κ = 0.87). On the other hand, the diagnostic performance of the MSCT images was relatively lower, with a weighted κ value of 0.78, which still indicates a substantial diagnostic agreement. Thus, the 3D imaging and reconstruction could raise the diagnostic accuracy of preoperative diagnosis on the PVTT type when compared with MSCT. This is partly because a correct evaluation of the PVTT location and extent based on MSCT images requires a full understanding of the imaging characteristics of PVTT in the 3 phases of contrast CT images which were frequently atypical. In addition, there are the normal and variant anatomy of the portal vein system, which makes interpretation of 2D images even more difficult. The 3D imaging, however, could provide more intuitive images and can overcome the difficulties of converting 2D images into three-dimensional models in the surgeon's mind which requires training and experience before this can be accomplished.

Complete resection of both the tumor and the PVTT is essential to improve the oncological prognosis of HCC patients with PVTT. For PVTT confined to the ipsilateral branch of the portal vein (type I/II), en-bloc resection of the primary tumor and the PVTT is recommended because this procedure would theoretically eliminate any possible residual tumors which are adherent to the portal vein wall. This operation also prevents dissemination of tumor cells during thrombectomy.4, 5, 17 However, there are still controversies over the management of PVTT which has extended into the contralateral branch or encroached onto the main trunk of the portal vein (type III/IV). For these patients, en-bloc resection followed by reconstruction of the portal vein has been reported to be associated with higher operative morbidities and mortalities.4, 22 In this study, we applied the en-bloc procedure for HCC patients with type I/II PVTT by extending the resection plane or by carrying out anatomical resection whenever the liver remnant was adequate. When compared with the conventional MSCT, the more accurate classification of the PVTT type by the preoperative 3D imaging and reconstruction contributed to the improved rate of en-bloc resection. However, on multivariate analysis there was no significant impact of en-bloc resection on postoperative survival. This is probably because in this study whether or not to carry out en-bloc resection depended on the type of PVTT. For patients with type III/IV PVTT which formed the majority of our cohort, thrombectomy was inevitably carried out. Meanwhile, multivariate Cox regression analysis could not be carried out on patients with type I/II PVTT because the sample size (n = 41) was too small as this could lead to a type II statistical error. Therefore, we speculated that the improved en-bloc resection rate helped to decrease the rate of residual tumor in the portal venous system is a reason for the better postoperative survival in the 3D reconstruction group. Well-designed randomized studies are still needed to further verify this speculation.

For the surgical treatment of HCC with PVTT, the location and the severity of PVTT have been reported to be important prognostic factors, despite different classification systems of PVTT were used.2, 5, 6, 13, 17, 23 In our study, using Cheng's classification of PVTT, those with PVTT involving the main trunk of the portal vein or the superior mesenteric vein (type III/IV) showed significantly poorer survival than the patients with PVTT in the ipsilateral branch of the portal vein (type I/II), which is consistent with the results of other reported studies. The effect of 3D reconstruction on the oncological outcome of HCC has not been evaluated by any other studies. Our result showed that the use of preoperative 3D imaging and reconstruction in surgical resection acted as a protective factor for both HCC recurrence and HCC-related death. For the limitation of our study design, including the non-randomized assignment, disadvantage of retrospective evidence and inconsistent treatment strategy for postoperative recurrence, considerable bias may exist. Nevertheless, we assume this protective effect of 3D imaging and reconstruction as a result of many factors which included the more accurate preoperative classification of PVTT, the optimized surgical procedure guided by 3D simulation, as well as the improved rate of en-bloc resection.

In conclusion, the 3D imaging and reconstruction allowed a stereoscopic depiction of HCC with PVTT and provided an accurate simulation of the operative procedure. In the surgical treatment of HCC patients with PVTT, the use of 3D imaging and reconstruction was efficient in facilitating the surgical procedure, in improving the rate of en-bloc resection and prolonging the postoperative survival.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the grants of the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups (No: 81221061); The State Key Project on Diseases of China (2012zx10002016016003); The China National Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists (No: 81125018); Chang Jiang Scholars Program (2013) of China Ministry of Education; China National Funds for National Natural Science (Nos: 81101511, 81472282).

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2015.10.007.

Financial disclosure

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.McGlynn K.A., London W.T. The global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: present and future. Clin Liver Dis. 2011;15:223–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2011.03.006. vii-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shuqun C., Mengchao W., Han C., Feng S., Jiahe Y., Guanghui D. Tumor thrombus types influence the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma with the tumor thrombi in the portal vein. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katagiri S., Yamamoto M. Multidisciplinary treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma with major portal vein tumor thrombus. Surg Today. 2014;44:219–226. doi: 10.1007/s00595-013-0585-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chok K.S., Cheung T.T., Chan S.C., Poon R.T., Fan S.T., Lo C.M. Surgical outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with portal vein tumor thrombosis. World J Surg. 2014;38:490–496. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2290-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X.P., Huang Z.Y. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in China: surgical techniques, indications, and outcomes. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2005;390:259–265. doi: 10.1007/s00423-005-0552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi J., Lai E.C., Li N., Guo W.X., Xue J., Lau W.Y. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2073–2080. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0940-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoue Y., Hasegawa K., Ishizawa T., Aoki T., Sano K., Beck Y. Is there any difference in survival according to the portal tumor thrombectomy method in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma? Surgery. 2009;145:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Endo I., Shimada H., Sugita M., Fujii Y., Morioka D., Takeda K. Role of three-dimensional imaging in operative planning for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery. 2007;142:666–675. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito S., Yamanaka J., Miura K., Nakao N., Nagao T., Sugimoto T. A novel 3D hepatectomy simulation based on liver circulation: application to liver resection and transplantation. Hepatology. 2005;41:1297–1304. doi: 10.1002/hep.20684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamanaka J., Saito S., Fujimoto J. Impact of preoperative planning using virtual segmental volumetry on liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2007;31:1249–1255. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wigmore S.J., Redhead D.N., Yan X.J., Casey J., Madhavan K., Dejong C.H. Virtual hepatic resection using three-dimensional reconstruction of helical computed tomography angioportograms. Ann Surg. 2001;233:221–226. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200102000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Association for the Study of the Liver, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi J., Lai E.C., Li N., Guo W.X., Xue J., Lau W.Y. A new classification for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:74–80. doi: 10.1007/s00534-010-0314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landis J.R., Koch G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llovet J.M., Bustamante J., Castells A., Vilana R., Ayuso Mdel C., Sala M. Natural history of untreated nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for the design and evaluation of therapeutic trials. Hepatology. 1999;29:62–67. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Treut Y.P., Hardwigsen J., Ananian P., Saisse J., Gregoire E., Richa H. Resection of hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombus in the major vasculature. A European case-control series. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:855–862. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X.P., Qiu F.Z., Wu Z.D., Zhang Z.W., Huang Z.Y., Chen Y.F. Effects of location and extension of portal vein tumor thrombus on long-term outcomes of surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:940–946. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohkubo T., Yamamoto J., Sugawara Y., Shimada K., Yamasaki S., Makuuchi M. Surgical results for hepatocellular carcinoma with macroscopic portal vein tumor thrombosis. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:657–660. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konishi M., Ryu M., Kinoshita T., Inoue K. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with direct removal of the tumor thrombus in the main portal vein. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1421–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen G., Li X.C., Wu G.Q., Wang Y., Fang B., Xiong X.F. The use of virtual reality for the functional simulation of hepatic tumors (case control study) Int J Surg. 2010;8:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brouwer K.M., Lindenhovius A.L., Dyer G.S., Zurakowski D., Mudgal C.S., Ring D. Diagnostic accuracy of 2- and 3-dimensional imaging and modeling of distal humerus fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:772–776. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka A., Morimoto T., Yamaoka Y. Implications of surgical treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombi in the portal vein. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujii T., Takayasu K., Muramatsu Y., Moriyama N., Wakao F., Kosuge T. Hepatocellular carcinoma with portal tumor thrombus: analysis of factors determining prognosis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1993;23:105–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.