Abstract

Background

Resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma continues to carry a poor prognosis. Of the controllable clinical variables known to affect outcome, margin status is paramount. Though the importance of a R0 resection is generally accepted, not all margins are easily managed. The superior mesenteric artery [SMA] in particular is the most challenging to clear. The aim of this study was to systematically review the literature with specific focus on the role of a SMA periadventitial dissection during PD and it's effect on margin status in pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Study design

The MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane databases were searched for abstracts that addressed the effect of margin status on survival and recurrence following pancreaticoduodenectomy [PD]. Quantitative analysis was performed.

Results

The overall incidence of a R1 resection ranged from 16% to 79%. The margin that was most often positive following PD was the SMA margin, which was positive in 15–45% of resected specimens. Most studies suggested that a positive margin was associated with decreased survival. No consistent definition of R0 resection was observed.

Conclusions

Margin positivity in resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma is associated with poor survival. Inability to clear the SMA margin is the most common cause of incomplete resection. More complete and consistently reported data are needed to evaluate the potential effect of periadventitial SMA dissection on margin status, local recurrence, or survival.

Introduction

Among patients who undergo pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDA), multiple clinical variables have been determined to be associated with postoperative prognosis.1, 2 Of these, margin status appears to be one of the most important.3 The American Joint Committee on Cancer staging guidelines have attempted to standardize the pathologic evaluation of PD specimens to facilitate margin assessment.4 According to these guidelines, PD specimen margins that should be evaluated by the pathologist include the pancreatic neck, bile duct, duodenum, stomach, as well as the superior mesenteric artery margin. The last of these margins, referred to as the SMA- or uncinate-margin, is specifically emphasized. Recent work by Verbeke et al., has illustrated that standardization of the histopathological examination of PD specimens can allow for a tighter correlation between histological staging and outcomes.5, 6

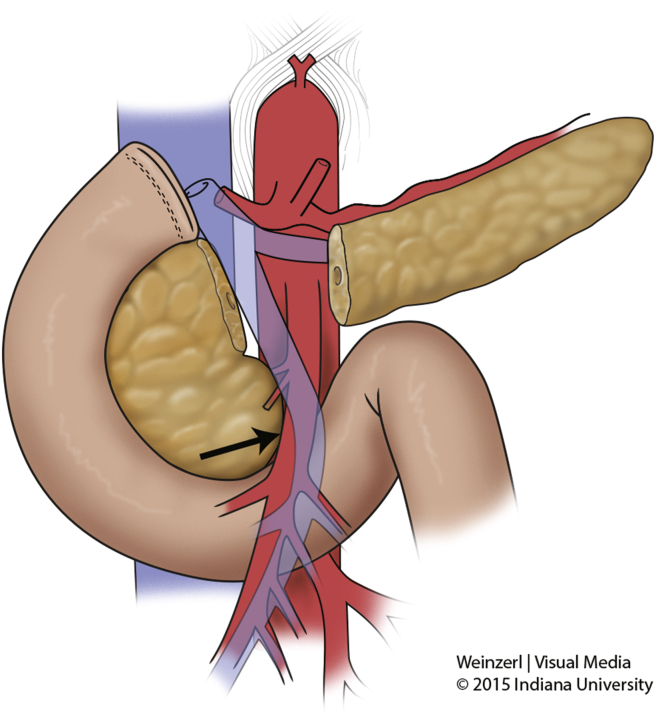

The SMA margin comprises the tissue that connects the uncinate process to the right lateral border of the proximal 3–4 cm of the SMA (Fig. 1). PDA has a propensity to spread through this tissue along the perineural autonomic plexus that surrounds the artery. The SMA margin is similar to the mesorectal margin emphasized during rectal surgery. However, the SMA cannot be removed and reconstructed at surgery in the absence of considerable morbidity. Many surgeons therefore strongly recommend that a periadventitial dissection of the SMA be performed at PD to skeletonize the right lateral aspect of the vessel from the uncinate process and adjacent tissues, to maximize the likelihood of obtaining a negative margin in the retroperitoneum.

Figure 1.

Superior mesenteric artery margin. Negative resection margin in the uncinate process is complicated by its proximity to the superior mesenteric artery

Although this recommendation is commonly made, the association between the status of the SMA margin and oncologic outcomes is unclear. Indeed, the incidence of a positive SMA margin and any association between margin status and outcome may also reflect “tumor biology” rather than surgical approach or technical skill.1, 7 The contribution of this specific surgical technique to postoperative outcome is therefore incompletely understood. The aim of this systematic review of the literature was to determine current reporting practices and the effect on outcomes of performing a periadventitial dissection of the SMA during PD.

Methods

The MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane databases were searched for English-language articles published from January 1990 through January 2014 that addressed the effect of margin status on survival and recurrence following PD. Search terms for “pancreas,” “retroperitoneal margin,” “pancreaticoduodenectomy,” “Whipple,” “margin,” “SMA dissection,” “mesopancreas,” “retroperitoneal dissection,” “morbidity,” and “uncinate dissection” were queried both in isolation and combination; duplicate references were removed prior to analysis.

The two investigators who performed the primary search (SAA and NJZ) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all returned references regardless of publication status to identify studies for inclusion in the analysis. Inclusion criteria dictated that articles selected for analysis focused on margin status following PD, and reported outcomes related to margin status. Review articles, and studies failing to document follow-up interval were excluded. All identified articles were examined using a predesigned proforma and the data collected were entered into a database for subsequent analysis. Articles selected for the analysis were specifically scrutinized for standardization of the surgical technique for SMA dissection, pathologic evaluation of the retroperitoneal margin, and margin status-related outcomes including local recurrence and overall survival. The methodological quality of studies was assessed for a minimum Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) level of 2C.8

Results

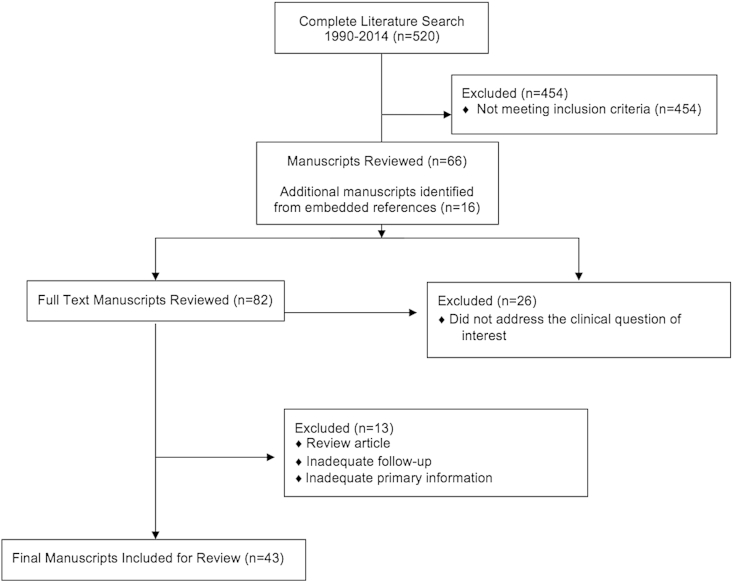

The initial search yielded 520 unique articles; from these, 43 were selected for quantitative analysis. Fig. 2 documents flow of references through the systematic review. The articles selected for analysis focused specifically on pancreas cancer, commented on margin status following PD, and reported outcomes related to margin status. Of the 43 articles selected, 5 were prospective trials; the others were retrospective reviews of institutional databases (37 articles) or national registry data (1 article). The overall reported incidence of a R1 resection ranged from 16% to 79%. The margin that was most often positive following PD was the SMA margin. It was positive in 15–45% of resected specimens, and was implicated in 46–88% of R1 resections.

Figure 2.

Flow of references through the review. The above diagram illustrates the assessment and allocation of references through the systematic review

Retrospective studies of margin status, survival, and local recurrence

Thirty-eight retrospective studies meeting the eligibility criteria were evaluated with a minimum evidence level of 2C (Table 1). Only 16 studies reported the status of different margins individually; among these 16 studies, the SMA margin was the most frequently positive margin. None specifically evaluated the potential effect of periadventitial SMA dissection on margin status, local recurrence, or survival.

Table 1.

Retrospective studies on margin status after pancreatoduodenectomy

| R0 definition category | n studies, (n combined patients) | R1 median% | SMA+ median% | Studies reporting observed effect of margin status on survival | Studies reporting observed effect of margin status on LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R0 not defineda | 16 (3674) | 35% (range 16–60) | 50% (range 46–73) | 14 + 2 – 0 NR |

1 +0 – 15 NS |

| R0 = 0–1 mmb | 14 (16,022) | 28% (range 17–64) | 63% (range 55–88) | 11 + 3 – 0 NR |

1 + 2 – 11 NR |

| R0 = >1 mmc | 8 (1201) | 57% (range 34–79) | 47% (range 38–80) | 8 + 0 – 0 NS |

0 + 1 – 7 NR |

Abbreviations: SMA+, superior mesenteric artery responsible for R1 designation; LR, local recurrence; NR, not reported; +, positive association; –, no association. The grade of evidence of all papers is 2C.8

Among the 38 retrospective studies, 33 concluded that a positive resection margin (any margin) correlated with poorer overall survival, whereas 5 reported that margin positivity did not influence survival. Only 5 studies commented on the influence of margin status on local recurrence: three studies found that margin status had no effect on the incidence of local recurrence, and 2 found that the local recurrence rates of patients with positive resection margins were higher than those of patients with negative resection margins.

Prospective studies of margin status, survival, and local recurrence

Since 1990, five prospective randomized studies (Table 2) from Europe and North America have investigated the influence of resection margins on survival and local recurrence following PD.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Only one of these prospective studies specifically addressed the loci of margin positivity13; this study found that SMA margin positivity was significantly affected by R0 definition and ranged from 23% positivity at 0–1 mm clearance to 58% positivity at >2 mm clearance. No prospective studies specifically evaluated the potential effect of periadventitial SMA dissection on margin status, local recurrence, or survival.

Table 2.

Prospective studies on the margin status and pancreatoduodenectomy

| Author, year | n | R0 definition | Patients with margin-positive resection (%) | Effect of margin status on survival | Grade of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klinkenbijl et al., 1999 | 218 | None | 22 | NR | 2C |

| Neoptolemos et al., 2004 | 289 | None | 18 | + | 2A |

| Regine et al., 2008 | 451 | None | 34 | + | 2A |

| Oettle H et al., 2013 | 368 | None | 17 | + | 2A |

| Delpero et al., 2014 | 150 | Stratified

|

Stratified

|

+ | 2A |

Abbreviations: NR, not reported. The grade of evidence was assessed by the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) level of 2C.8

In addition to the variable or absent reporting of R0 definitions noted, several other causes of heterogeneity were identified across studies (Table 3). Although all 43 of the included studies utilized patient survival as a primary endpoint, margin localization, local recurrence and systemic recurrence rates were inconsistently reported. Operative technique used to address the vascular margin included documentation of a periadventitial dissection in 11/43 studies.

Table 3.

Reporting practices in literature involving margin status after pancreatoduodenectomy

| Margin status reported | Periadventitial dissection of SMA reported | Local recurrence rate reported | Systemic recurrence rate reported |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Not localized 27/43 SMA 17/43 Pancreatic neck 15/43 Duodenum 4/43 Bile duct 11/43 |

Yes 11/43 No 32/43 |

Reported 11/43 Not reported 32/43 |

Reported 10/43 Not reported 33/43 |

Reporting practices of localized margin positivity, periadventitial SMA dissection, local recurrence, and systemic recurrence varied among studies identified within this review.

Discussion

Modern advancements to the surgical management of pancreatic carcinoma have centered upon improved identification and selection of operative candidates. Adjuvant therapies, evolving operative and postoperative management strategies have also had measurable effects on mortality and morbidity rates. Despite these advances, the current 5-year survival of patients undergoing operation with curative intent only approaches 25%.1 Moving forward, better understanding the variables that affect prognosis will be paramount to optimizing surgical management of pancreatic carcinoma. Gene mutation analysis and biomarker studies are currently promising but have yet to offer direct clinical application.14, 15 At the tissue level, margin status, poorly differentiated histology, larger tumor size, lymph node or vascular involvement, and perineural spread have all been identified as indicators of poor prognosis.2, 3, 16, 17, 18 Although margin status has recently received considerable attention, there has been infrequent emphasis given to the locus of margin positivity.

This study systematically reviews the literature on the topic of margin status after resection for pancreatic cancer. The SMA margin is most commonly positive in R1 resections. It is positive in up to 45% of patients undergoing operation with curative intent. This is most likely related to the close proximity of the tumor to the perineural plexus surrounding the SMA and the inability to resect additional tissue when the surgeon is confronted with a positive margin along the artery. Unfortunately the current body of literature does not support a quantitative meta-analysis. Several methodological limitations affecting the included retrospective studies are worthy of discussion. First, a standardized surgical technique used to clear the margins (e.g., whether a periadventitial dissection of the SMA was performed in all cases) was not routinely reported. Furthermore, the definitions of “R0” and “R1” were not applied consistently: 16 studies did not provide a specific definition of an R0 resection, 14 reports defined R0 as the microscopic absence of any tumor cells at the margin, and 8 reports, mostly from European investigators, defined an R0 resection as no tumor cells >1 mm from the cut edge of the specimen (Table 1). Not surprisingly, investigators who applied more stringent definitions of R0 resection (i.e., a clear margin >1 mm) reported higher rates of R1 resection. A standardized system for naming, processing and evaluating the surgical margins was not applied consistently. Finally, many studies used both univariate and multivariate analyses to assess the association between margin status and survival. In some of these studies, the univariate analysis, but not the multivariate analysis, revealed that margin status significantly affected survival. In other studies, the effect of margin status on survival was evaluated by comparing Kaplan–Meier survival curves for margin-negative patients to those of margin-positive patients (e.g., by Cox log-rank analysis).

Although the prospective studies included in this review associate margin status with survival, their heterogeneity also prohibits meta-analysis. Three of the five studies did not mandate that a standard surgical technique be used or a pathologic review be performed, and only two of the studies specifically excluded patients with R2 resections. As an example, the Charité Oncologie 001 study11, 19 randomized 354 patients to surgery followed by observation or adjuvant gemcitabine. The authors reported an overall margin-positive rate of 17% and found that gemcitabine improved survival following either margin-positive or margin-negative resection but seemed to offer more benefit following margin-positive resection. However, no specific information about the SMA margin or its association with either survival or patterns of recurrence was provided. Although one prospective study reported the oncologic status of the SMA margin independently, it did not independently link arterial margin positivity to recurrence or survival outcomes. Furthermore, this study found that SMA margin positivity was significantly affected by R0 margin definition distance. This finding is not surprising as when systematically inked, tumor clearance margin was found to range from 0.2 to 30 mm, further underscoring the need for a unified R0 margin definition.13

In addition to pathology reporting at the SMA margin, the pancreatic neck, bile duct and duodenal margin are also important in determining outcomes. Not surprisingly, technical details of margin clearance and outcomes data (i.e. local and systemic recurrence) were quite heterogeneous as documented in Table 3. These variably reported findings further emphasize the critical need for standardized definitions and reporting of in order to accurately study outcomes of resected pancreatic cancer patients. Informed reporting will only be possible with standardized definitions.

Thus, the current literature supports the importance of a R0 resection in the surgical management of pancreatic carcinoma. The margin most often positive is the SMA margin. Both a unified definition of margin negativity and universal reporting of positive margin locus will be required to better understand outcomes for patients with tumor involvement at resected margins.

Although a periadventitial dissection of the right lateral aspect of the SMA is commonly advocated as a critical technical aspect of PD,16 no existing studies specifically address the impact of this technique on rates of margin positivity, local recurrence, or overall survival relative to a less radical resection. Similarly, “artery first” techniques have become a topic of recent interest in attempt to provide better local clearance at the SMA margin20; understanding the effect of these approaches would also benefit from more complete reporting within the literature.

The SMA margin is the most commonly positive margin following PD, and most prospective and retrospective studies demonstrate improved survival when negative margins are achieved. Thus although a periadventitial SMA dissection that maximizes clearance at the arterial margin would seem to offer intuitive benefit, the heterogeneity of reported data does not support a direct appraisal of this practice.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

This project was initiated as a component of the American College of Surgeons Operative Standards for Cancer Surgery. The first author is supported by the 2015 Research Fellowship Award from the Association for Academic Surgery Foundation and the 2015 Scientist Scholarship from the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

References

- 1.Neoptolemos J.P., Stocken D.D., Dunn J.A., Almond J., Beger H.G., Pederzoli P. Influence of resection margins on survival for patients with pancreatic cancer treated by adjuvant chemoradiation and/or chemotherapy in the ESPAC-1 randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2001;234:758–768. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benassai G., Mastrorilli M., Quarto G., Cappiello A., Giani U., Forestieri P. Factors influencing survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol. 2000;73:212–218. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(200004)73:4<212::aid-jso5>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nitecki S.S., Sarr M.G., Colby T.V., van Heerden J.A. Long-term survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Is it really improving? Ann Surg. 1995;221:59–66. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199501000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edge S.B., American Joint Committee on Cancer . 7th edn. vol. xiv. Springer; New York: 2010. (AJCC Cancer Staging Manual). 648 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menon K.V., Gomez D., Smith A.M., Anthoney A., Verbeke C.S. Impact of margin status on survival following pancreatoduodenectomy for cancer: the Leeds Pathology Protocol (LEEPP) HPB. 2009;11:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2008.00013.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verbeke C.S., Leitch D., Menon K.V., McMahon M.J., Guillou P.J., Anthoney A. Redefining the R1 resection in pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1232–1237. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raut C.P., Tseng J.F., Sun C.C., Wang H., Wolff R.A., Crane C.H. Impact of resection status on pattern of failure and survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246:52–60. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000259391.84304.2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heneghan C. EBM resources on the new CEBM website. Evid Based Med. 2009;14:67. doi: 10.1136/ebm.14.3.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klinkenbijl J.H., Jeekel J., Sahmoud T., van Pel R., Couvreur M.L., Veenhof C.H. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg. 1999;230:776–782. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199912000-00006. discussion 82–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neoptolemos J.P., Stocken D.D., Friess H., Bassi C., Dunn J.A., Hickey H. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1200–1210. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oettle H., Neuhaus P., Hochhaus A., Hartmann J.T., Gellert K., Ridwelski K. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA – J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310:1473–1481. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.279201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regine W.F., Winter K.A., Abrams R.A., Safran H., Hoffman J.P., Konski A. Fluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA – J Am Med Assoc. 2008;299:1019–1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delpero J.R., Bachellier P., Regenet N., Le Treut Y.P., Paye F., Carrere N. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a French multicentre prospective evaluation of resection margins in 150 evaluable specimens. HPB. 2014;16:20–33. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fong Z.V., Winter J.M. Biomarkers in pancreatic cancer: diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive. Cancer J. 2012;18:530–538. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31827654ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz N.A., Dehlendorff C., Jensen B.V., Bjerregaard J.K., Nielsen K.R., Bojesen S.E. MicroRNA biomarkers in whole blood for detection of pancreatic cancer. JAMA – J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:392–404. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard T.J., Krug J.E., Yu J., Zyromski N.J., Schmidt C.M., Jacobson L.E. A margin-negative R0 resection accomplished with minimal postoperative complications is the surgeon's contribution to long-term survival in pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg – Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2006;10:1338–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.09.008. discussion 45–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millikan K.W., Deziel D.J., Silverstein J.C., Kanjo T.M., Christein J.D., Doolas A. Prognostic factors associated with resectable adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Am Surg. 1999;65:618–623. discussion 23–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon H.J., An J.Y., Heo J.S., Choi S.H., Joh J.W., Kim Y.I. Predicting survival after surgical resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2006;32:37–43. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000194609.24606.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oettle H., Post S., Neuhaus P., Gellert K., Langrehr J., Ridwelski K. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA – J Am Med Assoc. 2007;297:267–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanjay P., Takaori K., Govil S., Shrikhande S.V., Windsor J.A. ‘Artery-first’ approaches to pancreatoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1027–1035. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad N.A., Lewis J.D., Ginsberg G.G., Haller D.G., Morris J.B., Williams N.N. Long term survival after pancreatic resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2609–2615. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouvet M., Gamagami R.A., Gilpin E.A., Romeo O., Sasson A., Easter D.W. Factors influencing survival after resection for periampullary neoplasms. Am J Surg. 2000;180:13–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fusai G., Warnaar N., Sabin C.A., Archibong S., Davidson B.R. Outcome of R1 resection in patients undergoing pancreatico-duodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol – J Eur Soc Surg Oncol Br Assoc Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1309–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han S.S., Jang J.Y., Kim S.W., Kim W.H., Lee K.U., Park Y.H. Analysis of long-term survivors after surgical resection for pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2006;32:271–275. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000202953.87740.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhlmann K.F., de Castro S.M., Wesseling J.G., ten Kate F.J., Offerhaus G.J., Busch O.R. Surgical treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma; actual survival and prognostic factors in 343 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishimura Y., Hosotani R., Shibamoto Y., Kokubo M., Kanamori S., Sasai K. External and intraoperative radiotherapy for resectable and unresectable pancreatic cancer: analysis of survival rates and complications. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richter A., Niedergethmann M., Sturm J.W., Lorenz D., Post S., Trede M. Long-term results of partial pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head: 25-year experience. World J Surg. 2003;27:324–329. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6659-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnelldorfer T., Ware A.L., Sarr M.G., Smyrk T.C., Zhang L., Qin R. Long-term survival after pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: is cure possible? Ann Surg. 2008;247:456–462. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181613142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sohn T.A., Yeo C.J., Cameron J.L., Koniaris L., Kaushal S., Abrams R.A. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas-616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg – Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2000;4:567–579. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ueda M., Endo I., Nakashima M., Minami Y., Takeda K., Matsuo K. Prognostic factors after resection of pancreatic cancer. World J Surg. 2009;33:104–110. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9807-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willett C.G., Lewandrowski K., Warshaw A.L., Efird J., Compton C.C. Resection margins in carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Implications for radiation therapy. Ann Surg. 1993;217:144–148. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199302000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winter J.M., Cameron J.L., Campbell K.A., Arnold M.A., Chang D.C., Coleman J. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: a single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg – Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2006;10:1199–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.08.018. discussion 210–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bilimoria K.Y., Talamonti M.S., Sener S.F., Bilimoria M.M., Stewart A.K., Winchester D.P. Effect of hospital volume on margin status after pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:510–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang D.K., Johns A.L., Merrett N.D., Gill A.J., Colvin E.K., Scarlett C.J. Margin clearance and outcome in resected pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol – Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2855–2862. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fatima J., Schnelldorfer T., Barton J., Wood C.M., Wiste H.J., Smyrk T.C. Pancreatoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma: implications of positive margin on survival. Arch Surg. 2010;145:167–172. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartwig W., Hackert T., Hinz U., Gluth A., Bergmann F., Strobel O. Pancreatic cancer surgery in the new millennium: better prediction of outcome. Ann Surg. 2011;254:311–319. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821fd334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hernandez J., Mullinax J., Clark W., Toomey P., Villadolid D., Morton C. Survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy is not improved by extending resections to achieve negative margins. Ann Surg. 2009;250:76–80. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ad655e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jarufe N.P., Coldham C., Mayer A.D., Mirza D.F., Buckels J.A., Bramhall S.R. Favourable prognostic factors in a large UK experience of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas and periampullary region. Dig Surg. 2004;21:202–209. doi: 10.1159/000079346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kimbrough C.W., St Hill C.R., Martin R.C., McMasters K.M., Scoggins C.R. Tumor-positive resection margins reflect an aggressive tumor biology in pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:602–607. doi: 10.1002/jso.23299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murakami Y., Uemura K., Sudo T., Hayashidani Y., Hashimoto Y., Ohge H. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival after surgical resection for pancreatic carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg – Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2008;12:534–541. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugiura T., Uesaka K., Mihara K., Sasaki K., Kanemoto H., Mizuno T. Margin status, recurrence pattern, and prognosis after resection of pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2013;154:1078–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tummala P., Howard T., Agarwal B. Dramatic survival benefit related to R0 resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in patients with tumor </=25 mm in size and </=1 involved lymph nodes. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2013;4:e33. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2013.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van den Broeck A., Sergeant G., Ectors N., Van Steenbergen W., Aerts R., Topal B. Patterns of recurrence after curative resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol – J Eur Soc Surg Oncol Br Assoc Surg Oncol. 2009;35:600–604. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagner M., Redaelli C., Lietz M., Seiler C.A., Friess H., Buchler M.W. Curative resection is the single most important factor determining outcome in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2004;91:586–594. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell F., Smith R.A., Whelan P., Sutton R., Raraty M., Neoptolemos J.P. Classification of R1 resections for pancreatic cancer: the prognostic relevance of tumour involvement within 1 mm of a resection margin. Histopathology. 2009;55:277–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gnerlich J.L., Luka S.R., Deshpande A.D., Dubray B.J., Weir J.S., Carpenter D.H. Microscopic margins and patterns of treatment failure in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 2012;147:753–760. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jamieson N.B., Chan N.I., Foulis A.K., Dickson E.J., McKay C.J., Carter C.R. The prognostic influence of resection margin clearance following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg – Off J Soc Surg Alimentary Tract. 2013;17:511–521. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-2131-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jamieson N.B., Foulis A.K., Oien K.A., Going J.J., Glen P., Dickson E.J. Positive mobilization margins alone do not influence survival following pancreatico-duodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2010;251:1003–1010. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d77369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kinsella T.J., Seo Y., Willis J., Stellato T.A., Siegel C.T., Harpp D. The impact of resection margin status and postoperative CA19-9 levels on survival and patterns of recurrence after postoperative high-dose radiotherapy with 5-FU-based concurrent chemotherapy for resectable pancreatic cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31:446–453. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318168f6c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pingpank J.F., Hoffman J.P., Ross E.A., Cooper H.S., Meropol N.J., Freedman G. Effect of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on surgical margin status of resected adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg – Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2001;5:121–130. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westgaard A., Tafjord S., Farstad I.N., Cvancarova M., Eide T.J., Mathisen O. Resectable adenocarcinomas in the pancreatic head: the retroperitoneal resection margin is an independent prognostic factor. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]